Yves here. It’s always useful to have a look at data to see if it confirms or contradicts one’s assumptions. Separately, the author raises a question in passing as to whether globalization has peaked. Lambert has seen signs of that in his shipping data as well as some of the articles he’s linked to. But is this a short or long-term term plateau?

By Michel Fouquin, Advisor, CEPI and Jules Hugot, Assistant Professor, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá. Originally published at VoxEU

Historians and economists generally identify two periods of trade globalisation, the first beginning around 1870 and the second during the 1970s. The column argues that new data from 1827 onwards shows globalisation beginning as trade barriers were lowered around 1840, and that both periods of globalisation were surprisingly fuelled by a regionalisation of world trade. If globalisation continues to grow in future, regionalisation may decline.

Most studies based on trade statistics date the emergence of the First Globalisation around 1870. These studies, however, generally rely on data that begins in 1870. To better understand the chronology of globalisation, we put together the most comprehensive bilateral trade dataset to date. It tells us that the First Globalisation began in Europe in the 1840s, before expanding to other continents later in the 19th century. Technological innovations (oceangoing steamships, transcontinental telegraph) and pro-trade policies (bilateral free trade treaties, the gold standard) of the second half of the 19th century are considered the sparks for globalisation. This can’t be the case if globalisation began before they were created.

To create the TRADHIST dataset, we collected more than 1.9 million bilateral trade flows from 1827 to 2014 (Fouquin and Hugot 2016b), using a common framework to make it possible to compare both periods of globalisation. Data for the 1827-1870 period have not been collected before now. To do this, we aggregated six pre-existing sources as well as data directly extracted from customs archives, particularly before 1870. We also provided series of aggregate exports and imports, GDP, exchange rates, and bilateral distance.

What Do Openness Rates Tell Us?

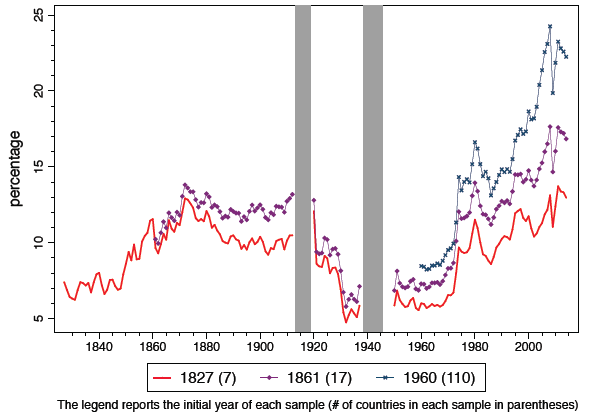

Figure 1 shows the evolution of export openness ratios (total exports/GDP) for three samples. Export openness doubles between 1827 and 1870 before stagnating until WWI. During the interwar period, openness falls below its level in the early 19th century, before rising again after 1960. It is only in the late 1970s that openness returns to the levels already reached a century before.

Figure 1 Export openness for three country samples: 1827-2014

Trade openness, however, is a crude measure of globalisation. Average openness in 2014 is 22% for our sample of 110 countries. But is that figure high or low, compared to what it would be in the absence of any international trade barrier?

Openness ratios are also sensitive to the global distribution of economic activity. If one country concentrated almost all economic activity, then aggregate openness would be very low because most goods would be produced and consumed in the same country. On the other hand, in a world of scattered economic activity, countries are naturally more interdependent. Trade openness is much higher. The difference between the two situations shows the degree of concentration of the world economy. It has nothing to do with the importance of trade barriers.

What we call ‘globalisation’ is the convergence between observed world trade and a theoretical situation in which international trade barriers would be equally as constraining as domestic ones. This means we need a theoretical prediction of what international trade would have been in the absence of obstacles specific to it.

The Cost of International Trade Barriers as an Indicator of Globalisation

Comparing observed trade to the prediction that emerges from the structural gravity model created by Head and Mayer (2014) evaluates the importance of the obstacles that are specific to international trade. The difference between observed trade and a counterfactual in which there would be no international trade barriers then reveals the aggregate cost that is specifically associated with international trade. These costs come from transportation and protectionist policies, but also factors like communication and exchange rate volatility (Jacks et al. 2008).

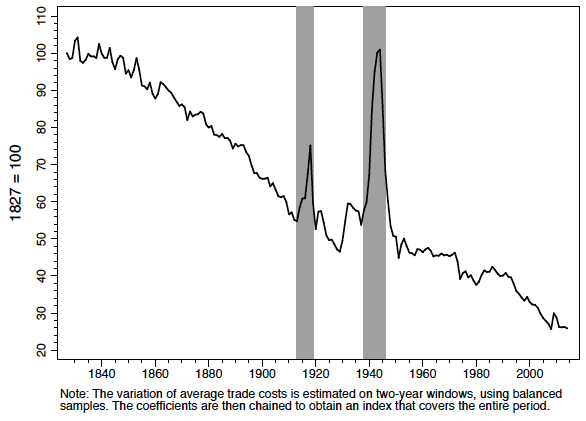

Figure 2 shows the evolution of aggregate international relative trade costs for the entire sample. It shows that trade barriers have fallen by more than 70% since 1840, relative to intranational trade barriers. Of this, 50% occurred in the period before the Great Depression, and 20% since 1960.

Figure 2 Evolution of average world international relative trade costs: 1827-2014

The First Globalisation had therefore already begun in the 1840s, before steamships, the telegraph or the gold standard, and before the wave of bilateral trade treaties signed by Western European countries in the 1860s. This was, however, a period of political stability in Europe after the Congress of Vienna in 1815. In the mid-19th century there were also unilateral reductions of trade protection, for example the repeal of the British Corn Laws in 1846. We found similar examples in other European countries. In the 1870s the Russian and American ‘grain invasion’ prompted higher tariffs in most of continental Europe. Trade costs, however, kept falling during this protectionist backlash, which suggests that it was compensated by the decline of other trade barriers.

After 1918, totalitarian regimes emerged in the USSR, Italy and Germany, and the protectionist measures that were adopted after the Great Depression condemned any possibility of returning to the liberal golden age.

High protectionism lasted until after WWII and the adoption of the GATT in 1947, which created multilateral liberalisation among developed economies. The Treaty of Rome (1957) began European integration, and internal customs barriers were abolished altogether in 1968. Finally, the generalisation of containerisation in the 1970s reduced transport costs.

The More Trade Grows, The More Distance Matters

Our research shows that globalisations are also regionalisations. Estimating the trade cost index of Figure 2 for various subsamples, we found that the decline of intra-European trade barriers after 1840 preceded the reduction of transatlantic trade barriers that happened around 1890. In Europe, the fall of trade costs in the northwest preceded the fall in the south.

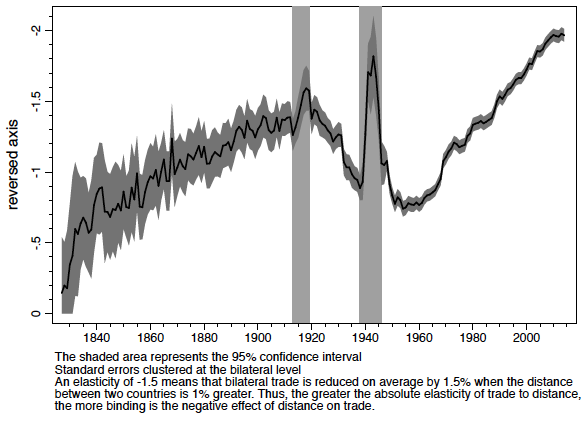

We also isolated the effect of distance across partners on bilateral trade and show that both globalisations were associated with an increase in distance elasticity (Figure 3). In 1830, a 10% difference in the distance between two countries would have reduced bilateral trade on average by 3%. On the eve of WWI, it would have reduced trade by 13%; and in 2010, the reduction would have been 19%. Combes et al. (2008) and Disdier and Head (2008) found this result for the second half of the 20th century, but it applied in the 19th century too.

Figure 3 Elasticity of bilateral trade to distance: 1827-2014

During both periods of globalisation, nations focused on long-distance trade. The First Globalisation was built on colonial trade, and the Second was inspired by European-American and Asian-American trade. So the major role of regionalisation in both globalisations is surprising. Several hypotheses may explain this phenomenon. First, pro-trade policies have been primarily adopted between neighbouring partners. The post-war integration of Europe is the most obvious example. Second, regionalisation may also be due to the increased complexity of the goods that are traded. Language and cultural barriers, which are highly correlated to distance, may have become more important. Also, the fixed costs associated with trade (for example information gathering on local preferences, loading and unloading) may also have decreased relative to the actual cost of carrying goods from one country to another, which is strongly linked with distance.

Future Globalisation and Regionalisation

The rise of international trade during the 19th century was supported by European liberal trade policies and, later, by technological improvements in transportation and communication. The Great Depression and the two world wars challenged this trend, while trade was partly reallocated to more distant partners due to geostrategic reasons and European colonialism. Both globalisation and regionalisation resumed in the 1960s.

But regionalisation has recently been fading, as the WTO has grown to include almost all countries in the world. The conversion of emerging and former socialist countries to free trade in the 2000s has stimulated long-distance trade.

The dynamism of trade between Asia and the rest of the world is expected to persist, especially with the emergence of new actors such as India and Bangladesh. On the other hand, continued sluggish growth in Europe could limit the growth of intra-European trade. If so, the margin of growth for trade seems to be particularly large for long-distance trade, which gives a central role to TTIP and the TPP.

Alternatively, perhaps globalisation has already peaked? The reorientation of Chinese growth to the domestic market should reduce its dependence on international trade. Growing inequalities in western countries generate opposition to globalisation. Renewable energies may reduce trade in hydrocarbons. Finally, the development of foreign direct investment substitutes local production for international trade.

See original post for references

Trade flows have been decisive for economic outcomes going back to Byzantium. In the 11th century the Byzantines cut a fateful deal with their quasi satellites in Northern Italy: help us defeat the menacing Turks and we will give you special trading privileges. Within a few years the Venetians and Genovese controlled the Byzantine economy and the wealth of Byzantium shifted to Northern Italy.

This bears more than a passing resemblance to the US decision to give South Korea, Japan and Taiwan privileged access to the US market in exchange for “help defeating Communism” – within a generation East Asia had taken over the most valuable parts of the US economy and the US began to spiral downward.

Globalization was already well established by the 18th Century. The financial infrastructure was there – corporations, insurance instruments, stock exchanges, central banks. The sea routes and the patterns of trade had been long established. Europeans had plugged into pre existing networks in Africa, the Indian and Pacific oceans.

It seems that, to economic historians, economic history only starts when their datasets are pretty enough.

Yeah, how is European colonialism — starting in, what, like the 15th century, or something — not “globalisation”? What about the Roman and Persian and Selucid empires? Wasn’t that globalisation? I think we’ve pretty much always lived in a globalised world, one way or another (if “globalised world” even makes sense).

Agreed. And I like I H S D’s comments. I suspect that the data sets are the usual sets pitched to northern European experience, with the nascent United States thrown in. So “globalization” only exists when the Anglo-American world takes note (our exceptional provincialism at work).

And to add to diptherio: The Roman empire engaged in global trade. Importation of silks from China and patterned cloth from India went on continuously.

Venice thrived on global trade. So the economic rise of the Serenissima in the twelfth century was based on trade (partly subsidized by the government). Marco Polo wasn’t an isolate. In fact, by 1815 and the Congress of Vienna, Venice was in decline, surpassed by Lisbon.

Speaking of the spice trade: And Portugal in the 1400s and 1500s. Discovery of the Azores, Madeira, and Cabo Verde islands. What was that about?

Exactly!

LOL Charles Mann makes a pretty good argument that globalization began in 1493 as a result of Columbus’s discovery.

I don’t know if it would impact the analysis but it seems a mistake to ignore him.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/1493:_Uncovering_the_New_World_Columbus_Created

Re Figure 1 … it seems clear that a gold standard stabilizes international trade … per 1870 etc and 1945 etc. Assuming that is a good thing. The increase in fiat prior to 1870 and post 1970 seems to be necessary for greater penetration of foreign trade into the GDP. Restraint of liquidity by a gold standard puts the breaks on that … as a percentage. The gross GDP can still expand. Fiat is like a sugar rush.

Nope, nada and no. What you are seeing is the Rothschilds/Gold “Standard’ stability colonial era. Which died in 1929. They outsourced capitalist famines and genocide to the “non-white” world. Capitalism is like a ponzi scheme. You have the banks who are the parasites who run the host. You have the aristocracy who became the hosts aka the capitalists and then you have the mass population who are the cattle.

A main reason nazism came was not some “communist” thing, who were really on the same coin, but different sides, but capitalism’s failings and Germany’s feelings they were becoming the next “colony”. The Gold Standards collapse was simply a forgone conclusion. From 1694 to 1931, the Bank of England was the worlds central bank. No other central bank mattered. They instituted commodity money and took over the world. The US was a rebellion to this “act” and stay free until the 1830’s. Part of the reason the US passed the Federal Reserve Act was exactly what happened and Glass Steagall put in the Nails to the Rothschild coffin.

The “Sugar rush” is nothing more than the world recovering from fall of the Rothschilds that created the mess of the first half of the 20th century.

The political side of political economics can get ugly. Assuming all that “smoked filled room” stuff is right, then it is malice and not stupidity that drives things … maybe not blowing up the world during the Cold War was a mistake. I have heard humanity likened to a persistent weed … but I prefer to think of us as dandelions.

Another thought: much of today’s increase in ‘trade’ is simply race-to-the-bottom labor market economics, where multinationals move their factories to wherever labor is cheaper. This of course cannot create prosperity, because people don’t get rich by becoming poor – er, I mean, ‘globally competitive’. Traditionally people got rich by building their own industries to service their own markets, letting wages rise enough to generate internal demand and erecting tariffs to insulate this virtuous cycle from poverty in other lands. Until very recently, that’s how the United States did it.

But now we have mass migration and pro-natalist policies popping up all over the place. That is likely going to make labor costs very low across the board (it’s called supply and demand: flood the market for labor and wages fall). In that case there will be no reason to move your factory to the other side of the world, if you can have labor just as cheap locally.

In other words: eventually the free movement of people will eliminate the pressure for the free movement of goods, as mass poverty becomes more universal.

Would you allow yourself to be exploited so ruthlessly in a stable, local market? I wouldn’t. This is how revolutions are born and the local industries are taken over by angry citizens.

Mass poverty can only be maintained by a corrupt elite running the society. To think this could be the natural state of affairs is the root of the neoliberal problem. I think the well healed have deluded themselves with their own propaganda into thinking that that social condition is possible to maintain. It is not. It is more wasteful of resources and effort than anything else- but because of human timidity, natures abundance, and cheep energy, can be ignored.

When it is finally realized how badly the citizenry has been treated, there will be much to account for. Poverty is another phenomena distorted by the elite. Poverty could be ended today if there was the will.

I find it revealing when people are forced to express their visions in simple, unmasked terms. Anyone who believes, or tolerates a society where its citizens are forced to live in abject poverty is a sociopath. This is what the capitalist world has wrought.

A world moving beyond the capitalist mindset is what I am counting on.

You are both wrong and right, wrong about just about everything, with the one exception of the universal poverty outcome – – much the same as the Roman Empire fell economically because a select few squeezed the workers more and more and more until there was nothing left to be squeezed – – typical pattern of sociopathic greedheads!

Bring back the broader, and more meaningful conception of Political Economy and some actual understanding can be gained. The study of economics cannot be separated from the political dimension of society. Politics being defined as who gets what in social interactions.

What folly. All this complexity and strident study of minutia to bring about what end? Human history on this planet has been about how societies form, develop, then recede form prominence. This flow being determined by how well the society provided for its members or could support their worldview. Talk about not seeing the forest for the trees.

The neoliberal experiment has run its course. Milton Friedman and his tribe had their alternative plan ready to go and implemented it when they could- to their great success. The best looting system developed-ever. This system only works with the availability of abundant resources and the mental justifications to support that gross exploitation. Both of which are reaching limits.

Only by thinking, and communicating in the broader terms of political economy can we hope to understand our current conditions. Until then, change will be difficult to enact. Hard landings for all indeed.

Well said. But unfortunately, I’d say that the Milton Friedman tribe might only be in the 2nd quarter.

If only the Milton Friedman tribe had interested itself in sports instead of economics. They could have argued that referees and umpires should be removed from the game for greater efficiency of play, and that sports teams would follow game rules by self-regulation.

While in traffic, I was thinking about that today. For some time now, I’ve viewed the traffic intersection as being a good example of the social contract. We all agree on its benefits. But today, I thought about it in terms of the Friedman Neoliberals.

Why should they have to stop at red lights. Wouldn’t the whole thing just work out more efficiently if you leave traffic lights and rules out of it? Just let everyone figure it out at each light, survival of the fittest.

Quite interesting that the 30 Glorious Years of first-world economic growth correspond to the period of very low “openness” and that increasing openness corresponds to declining economic performance. Because I had always heard that international trade is win-win.

It isn’t that impressive. The system was built into fighting “communism”(which was created from the mess from before) and everybody was united. Businesses wouldn’t deal with the same “requirements” now. Those 30 glorious years totally fell apart as well.

The lesson is, all systems die. There is no perfect one. Some “deaths” are big. Some are smaller.

What is “Globalization” and “Free Trade” really?… Does it encompass the slave trade, trading in narcotics, deforestation and export of a nation’s tropical hardwood forests, environmentally damaging transnational oil pipelines or coal ports, fisheries depletion, laying off millions of workers and replacing them and the products they make with workers and products made in a foreign country, trading with an enemy, investing capital in a foreign country through a subsidiary or supplier that abuses its workers to the point that some commit suicide, no limits on or regulation of financial derivatives and transnational financial intermediaries?… the list is endless.

As always, the questions are “Cui bono?”… “Who benefits”?… How and Why they benefit?… Who selects the short-term “Winners” and “Losers”? And WRT those questions, the final sentence of this post hints at its purpose.

Gathering and analyzing trade data is well and good but the analysis in this post is very unsatisfying. I get much confused by the categories this study defines —

Globalization: “the convergence between observed world trade and a theoretical situation in which international trade barriers would be equally as constraining as domestic ones”

Openess “export openness ratios (total exports/GDP)”

Regionalization: — not sure exactly

Aggregate Cost associated with international trade: “difference between observed trade and a counterfactual in which there would be no international trade barriers” — “transportation and protectionist policies, but also factors like communication and exchange rate volatility”

In terms of these constructs the authors detect mysteries in the data:

“The First Globalisation … begun in the 1840s, before steamships, the telegraph or the gold standard, and before the wave of bilateral trade treaties signed by Western European countries in the 1860s.” Why? This was a “period of political stability in Europe after the Congress of Vienna in 1815.”

“In the 1870s the Russian and American ‘grain invasion’ prompted higher tariffs in most of continental Europe. Trade costs, however, kept falling …” Why? “… it was compensated by the decline of other trade barriers.”

These are just two from among several surprising factoids revealed in the analysis of this trade data. The authors provide “interesting” but hardly satisfactory explanations for the anomalies they found.

“globalisations are also regionalisations” — I have no idea what that means and the header for this section “The More Trade Grows, The More Distance Matters” is also less than clear to me. The explanation in terms of the measured “Elasticity of bilateral trade to distance” doesn’t help me much.

The authors come up with “the major role of regionalisation in both globalisations is surprising” – What exactly does that mean and why is it surprising? The ready hypotheses on offer don’t help me. “But regionalisation has recently been fading …” because “WTO has grown … conversion … of former socialist countries to free trade ,,, stimulated long-distance trade.” If regionalisation is fading what does that mean?

Finally “… the margin of growth for trade seems to be particularly large for long-distance trade … gives a central role to TTIP and the TPP” — How did this sneak into the discussion?

End-to-end this post left me confused. It failed to clarify or explain the mysteries it discovered in the data. This conceptual frameworks and analysis in this paper do little to explain to me what is going on with trade. Maybe it’s all just over my head.

You’re not alone. I read through it three times and was still baffled by the bullshit. I also had a long list of objections but didn’t have the stomach to wade into the morass. It appears to me, however, that the authors of the paper made very basic errors of logic: “globalisations are also regionalisations” as you also noted, is very confusing. And globalization started in Europe before spreading to other continents? Not quite global, then. And on and on.

Thanks! I was worried I just couldn’t understand this stuff.

First thought was, an interesting chronology that roughly correlates to the emergence of the dismal “science” and how dogma seemed to be extrapolated from what may very well have been unreliable and/or incomplete stats of the time, and the precedents of the dismal theology being peddled as “science”. But after reading, couldn’t help thinking about “A Peoples History Of The United States” by Howard Zinn and this excerpt from chapter one:

“”History is the memory of states,” wrote Henry Kissinger in his first book, A World Restored, in which he proceeded to tell the history of nineteenth-century Europe from the viewpoint of the leaders of Austria and England, ignoring the millions who suffered from those statesmen’s policies. From his standpoint, the “peace” that Europe had before the French Revolution was “restored” by the diplomacy of a few national leaders. But for factory workers in England, farmers in France, colored people in Asia and Africa, women and children everywhere except in the upper classes, it was a world of conquest, violence, hunger, exploitation-a world not restored but disintegrated.

My viewpoint, in telling the history of the United States, is different: that we must not accept the memory of states as our own. Nations are not communities and never have been, The history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals fierce conflicts of interest (sometimes exploding, most often repressed) between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex. And in such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners.”

http://www.historyisaweapon.com/zinnapeopleshistory.html

Something I have wondered for some time, how does tourism fit into trade? With increasingly free movement of people as tourists whose spending impacts nations GDP, where does it fit in to discussions on globalization and trade?

Other things to consider:

– negative effects of immigration (skilled workers leave developing countries where they are most needed)

– environmental pollution

– destruction of cultures/habitats

– importation of western diet leading to decreased health

– spread of disease (black death, hiv, ebola, bird flu)

– resource wars

– drugs

– happiness

How are these “externalities” calculated?

That 1840 appearance of globalization was the result of British principles defeating democracy in the Napoleonic War.

It was in the aftermath of that quarter century of fighting that London bankers, notably Barings, Goldsmits, Rothschilds loaned cash to the Kings of Prussia, Russia, Austria and many others, requiring they securitise the debt on their stock exchanges.

That was the beginning of the globalization of debt-based finance. The inevitable immediate effect was a sudden flood of credit into the world economy – hence the appearance of a boom.