This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 604 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our third goal, well-deserved bonuses for our guest writers.

By Alexander Al-Haschimi, Economist, External Developments Division, ECB, Martin Gächter, Economist, Directorate General International and European Relations, ECB, David Lodge, Principal Economist, External Developments Division, ECB, and Walter Steingress, Research Economist in the International Macroeconomic Division, Banque de France; research affiliate; IZA. Originally published at VoxEU.

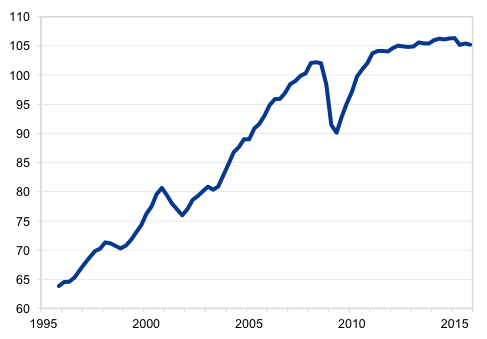

Exceptionally weak global trade growth over recent years has presented a puzzle to academics and policymakers alike.1 Annual world import growth has fallen below its long-run average since mid-2011 and remained there since, representing the longest period of below-trend growth in nearly half a century. Even more importantly, the link between global production and trade appears to have changed.2 While global trade grew at approximately twice the rate of global GDP prior to the Global Crisis, the share of trade in global GDP has discontinued its strong upward trend and largely stagnated over recent years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ratio of Global Imports to GDP (ratio of levels, quarterly data)

Source: National sources.

Notes: Real imports of goods and services. Real global GDP is aggregated with market exchange rates. The last observation refers to 2015Q4.

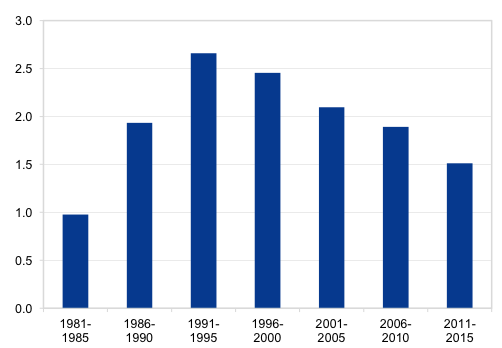

Pre-crisis trade elasticities have, however, also shown considerable variation over time, with the ratio of global import to GDP growth fluctuating significantly prior to the Great Recession (Figure 2). In fact, the growth ratio peaked in the mid-1990s, and has gradually declined thereafter.3 A recent study by an expert network of European central banks4 finds that the decline in this ratio is primarily due to structural factors, which had temporarily lifted the income elasticity of trade significantly above unity (IRC Task Force 2016). More recently, these push factors have largely run their course and thus provide less support to trade growth. From this perspective, the current environment therefore reflects a normalisation of the trade elasticity towards its long-run value of unity.

Figure 2. Ratio of Global Import Growth to Global GDP Growth (ratio of growth rates; annual data)

Source: IMF WEO.

Notes: Real imports of goods and services. Real global GDP is aggregated with market exchange rates. The last observation refers to 2015.

Specifically, the study shows that the change in the global trade-income relationship between the pre-crisis period and more recent years is driven by both compositional as well as structural effects. The former are not necessarily structural and can reverse over the medium term. The latter, on the other hand, alter the fundamental relationship between trade and economic activity also at the country level. These two factors each contribute roughly half to the overall decline in the trade elasticity, respectively.

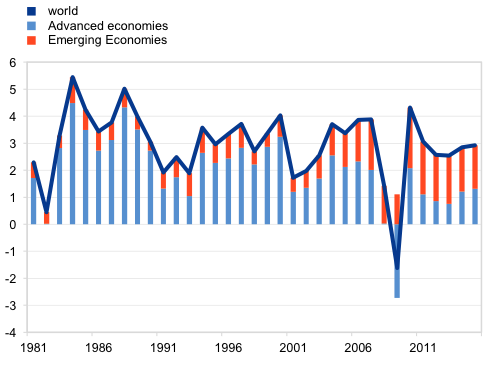

Among compositional effects, the geographical shift in economic activity has played a key role. The past decade was characterised by significant changes in the relative contributions of advanced and emerging economies to global growth and trade, with the contribution of the latter in global GDP increasing considerably (Figure 3). Since advanced economies typically exhibit higher trade elasticities than their emerging market counterparts, their decreasing importance in the global economy has implications for the global trade elasticity (Slopek 2015). In fact, a simple decomposition exercise shows that up to half of the decline in the global trade elasticity is attributed to the relative demand shift from advanced to emerging economies. The second compositional factor is linked to shifts in activity to demand components that are less trade-intensive (Bussière et al. 2013). In particular, investment has been weak after the Global Crisis among advanced countries, also contributing to the global trade weakness.

Figure 3. Global GDP Growth Contributions (annual percentage changes; percentage points)

Source: World Bank (WDI), IMF (WEO database), Haver Analytics and authors’ calculations. Aggregation based on market exchange rates.

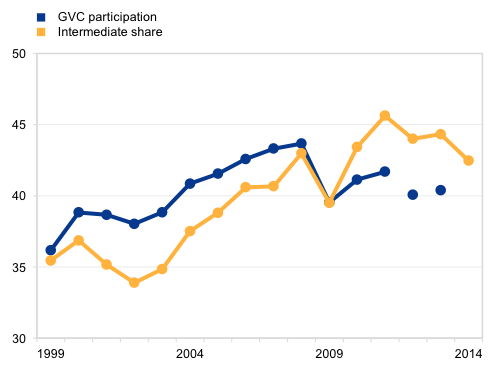

At the same time, several structural developments have additionally lowered trade elasticities at the individual country level. In particular, the expansion of global value chains had significantly supported gross trade growth in the 1990s and early 2000s, when intermediate components were increasingly shipped multiple times between economies along their production chains. Current indicators however suggest that the sharp rise in global value chains has stalled and possibly even reversed after 2011 (Figure 4), removing an important source of global trade growth. While the underlying reasons are manifold, anecdotal evidence points to expanding protectionist measures among the drivers of the global value chain slowdown. For instance, a recent ECB survey of large Eurozone firms found that two thirds of respondents list local content requirements as one of the main reasons for relocating production outside Europe (ECB, 2016). Local content requirements induce firms to increasingly source and produce in their export markets, which in turn substitute for earlier trade flows.

Figure 4. GVC participation versus share of intermediate goods in total goods imports (index)

Notes: Both measures exclude energy-related trade. The intermediate share is mean-variance adjusted to that of the GVC participation measure. The GVC measure is based on Borin and Mancini (2015) and extended for 2012-2013 with changes in the share of the intermediate goods indicator.

Another structural factor relates to financial frictions. In particular, financial development and better access to capital markets have been seen as an important factor in building up export capacities (Kletzer and Bardhan 1987, Beck 2002). While the empirical literature confirms the positive impact of financial development on the level of trade openness, recent analysis suggests that the marginal effect of finance on trade decreases considerably with the size of the financial sector (Gächter and Gkrintzalis 2016). The findings point to a threshold – estimated when private sector credit reaches around 100% of GDP – where further financial deepening is no longer associated with increasing trade relative to GDP. These non-linearities may also have played a non-negligible role in the global trade slowdown, as many countries have experienced substantial financial sector development in the two decades prior to the crisis. As financial sectors have matured, however, with many countries approaching the estimated threshold, the support provided by financial deepening for further trade growth has waned.

Finally, falling transportation costs and the removal of trade barriers have also considerably contributed to buoyant trade growth prior to the crisis. As these trade frictions have already reached rather low levels, however, further improvements and hence additional support to global trade growth will be limited going forward. In addition, recent evidence is pointing at a steady increase in protectionist measures and a lack of progress in global and even regional trade liberalisation initiatives.5

An assessment of the factors driving the trade slowdown thus suggests that the weakness is likely to persist, as both the shift in activity from advanced to emerging economies and the structural factors are unlikely to reverse over the medium term. In the absence of any further positive shocks to trade openness – such as renewed waves of multilateral trade liberalisations – the new normal for the global trade elasticity is likely to look broadly similar to the weak level observed over recent years. While strong recessions in a number of countries, particularly Russia and Brazil, as well as the slowing and ongoing transition of China’s economy to a more consumption-based and service-sector oriented economic growth model pushed global trade growth even below this new normal in 2015, world trade is unlikely to grow significantly faster than economic activity going forward. The great normalisation of global trade therefore implies that even a rebound of global GDP growth to pre-crisis levels would not lead to a significant recovery of global trade.

The world is full of pent up demand to restore growth.

In Greece the poor can no longer even afford bread.

2016– “Richest 62 people as wealthy as half of world’s population”

Inequality is the problem.

Just imagine the new demand if some of that wealth was re-distributed.

The new demand would spur new investment opportunities, there is no where to invest now due to the lack of demand and many investments have negative yields as the world is deluged with investment capital.

Time for a New Deal.

+1

After 2008.

The West went for monetary policy, China went for fiscal policy.

The West kept asset prices up but little trickled down to the real economy and it stagnated.

China became the new engine of global growth and its insatiable demand for raw materials led to booms in most of the emerging market economies.

Unfortunately, China had taken on its own version of neo-liberalism causing massive inequality.

The wealthy took their money out of China and invested in property, classic cars, fine art and luxury yachts as the global rich do.

Chinese consumption was always impeded by low wages and no welfare state. The lack of a welfare state ensured those lower down the scale had to save a large part of their wages for a rainy day and could not indulge in the zero savings rates of the West, where consumers spend everything they earn as they know there is a safety net to catch them if the worst comes to the worst.

Eventually China’s debt load became too high and it had to stop its fiscal stimulus.

China’s consumers were in no position for home grown consumption to replace western consumption. The wealthy Chinese, who had reaped most of the benefits from the boom, had stashed their cash abroad.

The Western consumer had never recovered because the West used monetary policy rather than fiscal policy.

Learning lessons from China and the West.

1) Fiscal policy works much better than monetary policy for getting the whole economy going.

2) Use Central Bank created money for fiscal policy so that you don’t hit a debt ceiling.

3) Don’t let the wealthy run off with all the money and recycle it through taxation.

Sorted.

+1

I disagree with sound of the suburbs. There are few investment opportunities in China. Banks pay no interest, real estate is questionable and high-priced and the stock market in China is obviously seen as a lottery. There’s just not much to invest in in China & that’s one reason people keep savings. And it’s a trad. Chinese cultural thing too.

Also the US is driven by consumer spending. We need more of it for the economy to grow. The social safety network in the United States is far too weak to be the thing that encourages people to spend every cent. It’s consumerism, wanting to keep up with your neighbors.

I wish the us would spend more on infrastructure and less on military. We should also gradually increase the SS max income cap so we avoid insolvency.

Market led democracy.

The wealthy have always supported an unequal distribution of land and capital as it works in their own self-interest.

Classical Economists never thought the poor would rise out of a basic subsistence existence as that was the way it had always been in five thousand years of human civilisation. Those at the top had always been able to live in splendid luxury for all of recorded history.

Organised labour movements in the 19th Century started to move the poor upwards out of that basic subsistence existence despite the best attempts of the wealthy to ensure the poor stayed where they had always been.

Universal suffrage posed problems for the wealthy and their desire to maintain the most unequal distribution of land and capital possible. One person, one vote meant the poor would get the majority of the votes.

The uprisings of the masses in the 1960s and union power of the 1970s indicated things were proceeding in a most unwelcome direction.

How about market led democracy?

Everyone votes through the markets and it expresses the aggregate wants of all participants.

2016– “Richest 62 people as wealthy as half of world’s population”

This is a voting scheme with the desired bias.

Also, the markets half the world’s population are voting in are just for food staples, even better.

In the early 1990s George Soros demonstrated he was more powerful than the 60 million people of the UK and forced the UK out of the ERM.

Market led democracy is not quite what it seems.

The UK currency is down; one person may have decided the 60 million people of the UK need to change direction.

The market led global economy.

Pre-2008 – boom

2008 – bust

Post-2008 – stagnation

It’s not all it’s cracked up to be.

Those with all the voting power enriched themselves to such an extent that they destroyed demand with inequality.

How is the global consumer these days?

1) The once wealthy Western consumer has had nearly all their high paying jobs off-shored. As a stop gap solution they were allowed to carry on consuming through debt. They are now maxed out on debt.

2) Japanese consumers have been living in a stagnant economy for decades.

3) Chinese and Eastern consumers were always poorly paid and with nonexistent welfare states are always saving for a rainy day. Western demand slumped in 2008 and the debt fuelled stop gap has now

come to an end.

4) The Middle Eastern consumers are now too busy fighting each other to think about consuming anything and are just concerned with saying alive.

5) South American and African consumers are busy struggling with economies that are disintegrating fast.

Oh dear, no wonder there is such subdued demand.

More stagnation?

With a market led economy are the wealthy ever going to vote to make themselves poorer?

More stagnation.

I have to agree, the idea that the commonwealth is a goal was kicked out in the thatche/rreagan counter reformations.

Their great victory was extinguishing expectaions.

http://www.the-utopian.org/post/53360513384/the-thirteen-commandments-of-neoliberalism

That is a good one

Bookmarked. Excellent analysis. Thanks!

I would like to hear your comments on publicly owned banking. Nationalized banks treated as a public utility. If money is a demon creating polarized wealth, then following the money trail with an eye to control of its power, seems a necessary enterprise.

Exceptionally weak global trade growth over recent years has presented a puzzle to academics and policymakers alike

They get a puzzle while they order everyone else an armed delivery of a shit sandwich?

May all their christmases be their last.

What is wealth? Do the piles of gold have a will? Do the rivers of dollars have a will? Do the Kansas plains have a will? No will at all. The will is reserved for those that are rich or in a reverse manner the rich have a will.

But how is that will manifested? The will seems to be a will because someone obeys someone else. The master is master while the serf is serf.The choice for the serf is death or obedience.

There is no accumulation of wealth. There is only manifestation of wills. The wills are enabled by the obedience of the obedient. And between them are the weapons. They are the threat that enables the will of the rich.

We are subjects to terror.

Growth? Those days are over.

Anyone who thinks we can grow forever is an idiot or an economist.

Unfortunately I don’t remember the author of that remark.

You (by which I mean, the wealthy) don’t need growth if you can grab an ever larger share of what’s left.

Of course, there is a limit to “what’s left,” and the wealthy have now grabbed and will continue to grab so much of what’s left, that there is almost nothing left for most people to simply get by, let alone “get ahead.”

This report comes from the ECB. We’d never get this info from the Fed. The diff between the US and the rest of the world is that we, in our hubris, pushed globalization in an attempt to stay rich and powerful ourselves. It worked in the 50s, began to fail in the 60s, and was done for in the 70s. That’s very timely feedback. Economics doesn’t fool around. I think this is a lovely turn of events. Because in the interim – between 1945 and now – we have come to our senses about war. And we’re gonna find sane solutions even tho’ it looks like we are crazier than ever.

“…we have come to our senses about war.” Sorry I don’t understand what you mean here.

I sincerely hope “we’re gonna find sane solutions even tho’ it looks like we are crazier than ever.” What brings you to that conclusion? I would appreciate any shiny baubles of insight to illuminate the gloom of the future I see facing us in Syria. — Not saying there aren’t any but I just don’t see them.

we might see sane solutions, but the people running our country won’t. very scary times.

This is where all the GDP growth since 2008 has come from: http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2015/09/china-s-economy

The article is mostly about China’s central bank, but the graph speaks to the other major central banks too.

By the way, good to see The Economist recognize that China was “monetizing” the trade imbalance with the US. Don’t know why they said it started in 2000 though, “The boom in its foreign-exchange reserves since 2000 translated directly into monetary growth at home”. They’ve been playing that game since 1982 or so.

And they were playing that game up until the wealthy in China had so much excess yuan they decided to engage in capital flight to call the bluff of their own central bank and its willingness to (not) lower the peg even more. Hence the last paragraph in the article about how the PBoC had to stimulate private lending as a substitute for QE.

Yes, all organic growth, I would say, lol.

“[A]ll organic growth” is seasonal…nominal debt grows mathematically and mostly presented ‘magi-matically’…when the divergence becomes undeniable, private debt write-downs and public spending towards full-capacity, would seem the only viable “Public-Private-Partnership”…

Hmmm…FTA…” two thirds of respondents list local content requirements as one of the main reasons for relocating production outside Europe (ECB, 2016). Local content requirements induce firms to increasingly source and produce in their export markets, which in turn substitute for earlier trade flows.”

Does anyone have thoughts on this passage?

The Asians are extreme protectionists, and want to export their manufactured – crappola and only import raw materials or it’s a load of self serving baloney that gives the ‘respondents’ cover for cutting the $20 per hour local labor and substituting cheap Chinese labor instead, or a combination of both.

I’m expecting the oppressed in China to go on a factory rampage, and choke off the flow of TVs. That will freak out the elite, because then they have one less avenue available to lie to us.

Economists have a throne at the policy table, but they will never pay for instigating the ecological and economic disaster that globalization is.

In another talking out of my hat moment, I will admit that one of the things that I have noticed in our discussions regarding trade agreements is how much of the focus is on agriculture and health. On those occasions when I’ve bothered thinking globally and not just domestically, I started toying with the idea that these agreements are not just about cementing corporate governance throughout the world, which of course they are, but also the divisions of the spoils. And that our overlords are not quite as clueless as I think most of the time.

What are the things people allocate their limited funds to regardless of how little they have: food, housing and health care. Now housing itself is not something that is trade driven, although some of the materials can be. And you would think the same could be said of health care -but much more of that can be traded with drugs and medical equipment. But the biggie is food. People have to eat.

Some of the overlords know they have killed demand. It is all about dividing the remaining spoils.

And as we’re seeing, once local consumption is committed to global production and local production is committed to global consumption, it’s damn near impossible to untie the resulting Gordian Knot again in time to react to local contingencies. Credit where credit is due: it’s an extremely clever system designed to enforce local helplessness before global forces, all without firing a shot in anger. Because markets! Because trade! Because efficiencies!

Nothing’s more efficient than death.

I have lurked here for some time, and this is my first post. Call me foily, but my take is that the PTB, at least in the US, could be preparing for a substantial population reduction.

This may become clear soon; I guess we’ll see. Hope I’m wrong.

Welcome in! Please explain further about your reasoning. I am thick about many things.

My own children seem less likely to give me grandchildren than I had hoped. Are there other signs of a substantial population reduction? How fast will the reduction be? We could have a ten-fold reduction just by changing the birth rate wrt. the death rate if we add a little time to the mix. It could be done without actively promoting an increase in the death rate. In general people in developed economies don’t have kids if they can’t support them — like now.

My theory If the citizens of USA and other rich countries out sourced good middle class jobs. if the bulk of them and us . People will take their money out in droves out of the banks. I am assuming the Armed forces will be mass desertions of them . I hate to say it political break up I like the Roman empire. What kept U.K. from collapsing after WW2 was The USA (Marshal Plan). I see violent actions against non whites with the formations right terrorists groups in America. IT happened In Russia with their civil war/revolution 1917. If it does happen will it be MAD Max movie Circa 1980″s not the crappy one last Year .

Lost again.

Skynet — a graceful shutdown of power is no longer sufficient. You must die through a surge of MegaWatt power [GigaWatts — too $$$$$ — and contributes too much glory to your extinction.].