Lambert here: Apparently, then, Neoliberal U plans to build “trust-based relations” and offer “personalised attention” by gutting tenured faculty, shifting the teaching load to contingent faculty, redistributing salaries to administrators, and socking money into fancy facilities. Let me know how that works out.

By Philip Oreopoulos, Professor of Economics and Public Policy, University of Toronto, and Uros Petronijevic, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, York University. Originally published at VoxEU.

Questions over the value of a university education are underscored by negative student experiences. Personalised coaching is a promising, but costly, tool to improve student experiences and performance. This column presents the results from an experiment comparing coaching with lower cost ‘nudge’ interventions. While coaching led to a significant increase in average course grades, online and text message interventions had no effect. The benefits of coaching appear to derive from the trust-based nature of relationships and personalised attention.

Policymakers and academics share growing concerns about stagnating college completion rates and negative student experiences. Recent figures suggest that only 56% of students who pursue a bachelors’ degree complete it within six years (Symonds et al. 2011), and it is increasingly unclear whether students who attain degrees acquire meaningful new skills along the way (Arum and Roska 2011). Students enter college underprepared, with those who procrastinate, do not study enough, or have superficial attitudes about success performing particularly poorly (Beattie et al 2016).

Personalised Coaching to Improve Outcomes

A promising tool for improving students’ college outcomes and experiences is personalised coaching. At both the high school and college levels, an emerging recent literature demonstrates the benefits of helping students foster motivation, effort, good study habits, and time-management skills through structured tutoring and coaching. Cook et al. (2014) find that cognitive behavioural therapy and tutoring generate large improvements in maths scores and high school graduation rates for troubled youth in Chicago, while Oreopoulos et al. (forthcoming) show that coaching, tutoring, and group activities lead to large increases in high school graduation and college enrolment among youth in a Toronto public housing project. At the college level, Scrivener and Weiss (2013) find that the Accelerated Study in Associates Program – a bundle of coaching, tutoring, and student success workshops – in CUNY community colleges nearly doubled graduation rates and Bettinger and Baker (2014) show that telephone coaching by Inside Track professionals boosts two-year college retention by 15% across several higher-education institutions.

While structured, one-on-one support can have large effects on student outcomes, it is often costly to implement and difficult to scale up to the student population at large (Bloom 1984). Noting this challenge, we set out to build on recent advances in social-psychology and behavioural economics, investigating whether technology – specifically, online exercises, and text and email messaging – can be used to generate comparable benefits to one-on-one coaching interventions but at lower costs among first-year university students (Oreopoulos and Petronijevic 2016).

Several recent studies in social-psychology find that short, appropriately timed interventions can have lasting effects on student outcomes (Yeager and Walton 2011, Cohen and Garcia 2014, Walton 2014). Relatively large improvements on academic performance have been documented from interventions that help students define their long-run goals or purpose for learning (Morisano et al. 2010, Yeager et al. 2014), teach the ‘growth mindset’ idea that intelligence is malleable (Yeager et al. 2016), and help students keep negative events in perspective by self-affirming their values (Cohen and Sherman 2014). In contrast to these one-time interventions, other studies in education and behavioural economics attempt to maintain constant, low-touch contact with students or their parents at a low cost by using technology to provide consistent reminders aimed at improving outcomes. Providing text, email, and phone call updates to parents about their students’ progress in school has been shown to boost both parental engagement and student performance (Kraft and Dougherty 2013, Bergman 2016, Kraft and Rogers 2014, Mayer et al. 2015), while direct text-message communication with college and university students has been used in attempts to increase financial aid renewal (Castleman and Page 2014) and improve academic outcomes (Castleman and Meyer 2016).

Can Lower-Cost Alternatives to One-On-One Coaching Be Effective?

We examine whether benefits comparable to those obtained from one-on-one coaching can be achieved at lower cost by either of two specific interventions (Oreopoulos and Petronijevic 2016). We examine a one-time online intervention designed to affirm students’ goals and purpose for attending university, and a full-year text and email messaging campaign that provides weekly reminders of academic advice and motivation to students. We work with a sample of more than 4,000 undergraduate students who are enrolled in introductory economics courses at a large representative college in Canada, randomly assigning students to one of three treatment groups or a control group. The treatment groups consist of:

- A one-time, online exercise completed during the first two weeks of class in the autumn;

- The online intervention plus text and email messaging throughout the full academic year; and

- The online intervention plus one-on-one coaching in which students are assigned to upper-year undergraduate students who act as coaches.

Students in the control group are given a personality test measuring the Big Five personality traits.

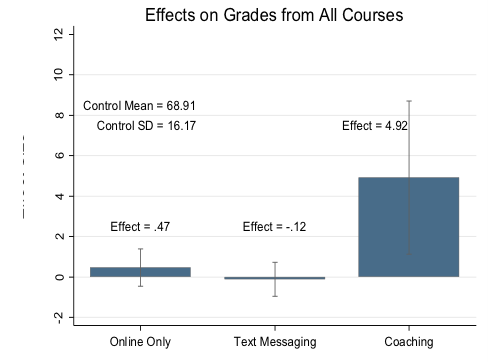

Figure 1 summarises our main results on course grades. Overall, we find large positive effects from the coaching programme, amounting to approximately a 4.92 percentage-point increase in average course grades; we also find that coached students experience a 0.35 standard-deviation increase in GPA. In contrast, we find no effects on academic outcomes from either the online exercise or the text messaging campaign, even after investigating potentially heterogeneous treatment effects across several student characteristics, including gender, age, incoming high school average, international-student status, and whether students live on residence.

Figure 1. Main effects of interventions

Our results suggest that the benefits of personal coaching are not easily replicated by low-cost interventions using technology. Many successful coaching programmes involve regular student-coach interaction facilitated either by mandatory meetings between coaches and students or proactive coaches regularly initiating contact (Scrivener and Weiss 2013, Bettinger and Baker 2014, Cook et al. 2014, Oreopoulos et al. forthcoming). Our coaches initiated contact and built trust with students over time, in person and through text messaging. Through a series of gentle, open-ended questions, the coaches could understand the problems students were facing and provide clear advice, ending most conversations with students being able to take at least one specific action to help solve their current problems.

Our text messaging campaign offered weekly academic advice, resource information, and motivation, but did not initiate communication with individual students about specific issues (e.g. help with writing or an upcoming mid-term). The text-messaging team often invited students to reply to messages and share their concerns but was unable to do this with the same efficacy as a coach, nor were we able to establish the same rapport with students. Our inability to reach out to all students and softly guide the conversation likely prevented us from learning the important details of their specific problems. Although we provided answers and advice to the questions we received, we did not have as much information on the students’ backgrounds as our coaches did, and thus could not tailor our responses to each student’s specific circumstances.

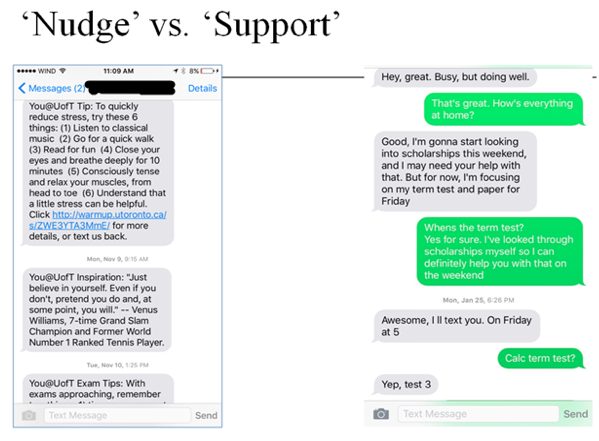

Our coaches were also able to build trust with students by fulfilling a support role. Figure 2 provides an example of how the coaching service was more effective than the text messaging campaign in this respect. The text messages attempted to nudge students in the right direction, rather than provide tailored support. The left panel of Figure 2 shows three consecutive text messages, in which we provide a tip on stress management, an inspirational quote, and a time-management tip around the exam period. As in this example, it was often the case that students would not respond to such messages. In contrast, the student-coach interaction in the right panel shows our coaches offering more of a supportive role rather than trying to simply nudge the student in a specific direction. The coach starts by asking an open-ended question, to which the student responds, and the coach then guides the conversation forward. In this example, the coach assures the student that they will be available to help with a pending deadline and shows a genuine interest in the events in the student’s life.

Figure 2. Distinguishing the text-messaging campaign and the coaching programme

Coaches also kept records of their evolving conversations with students and could check in to ask how previously discussed issues were being resolved. Although we kept a record of all text message conversations, a lack of resources prevented us from conducting regular check-ups to see how previous events had unfolded, which likely kept us from helping students effectively with their problem and from establishing the trust required for students to share additional problems.

Concluding Remarks

In sum, the two key features that distinguish the coaching service from the texting campaign are that coaches proactively initiated discussion with students about their problems and could establish relationships based on trust in which students felt comfortable to openly discuss their issues. Future work attempting to improve academic outcomes in higher education by using technology to maintain constant contact with students may need to acknowledge that simply nudging students in the right direction is not enough. A more personalised approach is likely required, in which coaches or mentors initially guide students through a series of gentle conversations and subsequently show a proactive interest in students’ lives. These conversations need not necessarily occur during face-to-face meetings, but the available evidence suggests that they should occur frequently and be initiated by the coaches. While such an intervention is likely to be costlier than the text messaging campaign in our study, it is also likely to be more effective but still less costly than the personalised coaching treatment.

“Personalised coaching is a promising, but costly, tool to improve student experiences …”

… that used to be called, in the long ago time before the App Store, office hours.

Back in the day when there were these non-administrative inefficiencies called tenure track faculty.

Surely Mechanical Turk can find a disruptive application in this space.

However also way back when few students bothered to go to faculty office hours. (early 1970s) . In addition how many students go to the departmental seminars in their major field? Again undergraduate attendance at them is low. Or join clubs in their major field that invite faculty to come talk about their research (which is easy to get a prof to do to talk about his research). (Today of course you could do seminars and the like via podcasts etc).

However of course the mentoring also takes student time which may also be scarce.

It’s still the case that students hardly ever go to office hours, and many who do, if Rate My Professors is anything to go by, do so solely to ingratiate themselves upon their teacher, which, frankly, often works.

The vast majority who don’t go, if I had to speculate, have a nigh pathological fear of being shown as not knowing what they’re supposed to be doing. I had something happen in one of my classes this year, where a student raised her hand and said straight out that she didn’t know what a particular word I kept using (iconography, I think…) meant, and immediately several other students sighed “thank god” that someone asked, because they had no idea as well. If that one young woman hadn’t asked, I imagine no one would have bothered to clear up their confusion. And their work makes clear that they are regularly confused about what they need to do but are unwilling to simply ask for a clarification.

Sounds like in the opening class a statement that there is no such thing as a stupid question could help. Recall that at West Point for 1st year students there were three answers yes sir, no sir, and I do not understand sir.

It may well also be a fear of being shown to be ignorant or stupid by asking a question.

Another way to express it would be to relate that in doing work to build the general and special theories of relativity Einstein asked simple question such as what happens if you try chase a light beam, or rode on one.

I would love for someone to do comparison of the cost savings in the decrease the in full-time faculty vs. the increase in costs in more administrators and more staff on the student services side of the ‘house’. I’d bet that it is, at best, a wash and, at worse, more money is being spent on administrators and student services staff than was spent on full-time faculty… if students do better with more contact, it seems to me the simple way to do that would be to offer smaller class sizes with full-time faculty who have offices with office hours and the support of well paid TAs who can offer seminars, tutorials and one-on-one help when needed. That would provide the regular contact required wouldn’t it?

Mostly, we need to stop treating students like customers and start treating them like students again.

“Mostly, we need to stop treating students like customers and start treating them like students again.”

Ding Ding Ding Ding! We have a winner!

Won’t happen though. Alas.

One metric that is difficult to come by but some research tries to estimate: how much of student fees goes to front line services (academic staff, library, counselors only) and this appears to have shifted, on average, from roughly 70% in the 1960s to under 40%. today; obviously there are big differences by types of schools. What it does imply (just because of their weight in overall averages of anything in higher education) is that most of the shift occurred at state/publicly funded colleges and universities. This is consistent with other studies showing that teaching in the first two years at state universities is done by graduate students and adjuncts; adjuncts are especially common in required English classes. This is not the old model of large lectures plus sections taught by Phd students; this is Phd students and adjuncts doing the teaching. What they specifically do not have time to provide is the ‘coaching’ element.

We work with a sample of more than 4,000 undergraduate students who are enrolled in introductory economics courses at a large representative college in Canada . . .

The headline could read “Four Thousand Canadian Students Get Lobotomies at University”.

A “text/email messaging campaign” is just nagging your students.

If I was on the recieving end of that impersonalized nonsense I would become resentful and unreceptive.

I have a degree in economics I focused on math but most of my peers did not. With the exception of the math classes I really learned nothing. I can honestly say I learned more in high school. I hope this has not been the case for most people at other universities.

Since most economics as taught is just neolib drivel I’d suggest learning nothing of it (aka surviving the indoctrination) has to count as a big win.

My brother is a labor economist and he has researched the relationship between the number of hours a student works during school terms and their life time earnings. He found that there is an inverse relationship between the number of hours a student works during semesters and their life time earnings. Of course part this effect is due to a student’s family / financial resources but he said he adjusted for that in his research. This article seems to show that our current factory model for education may be ready for replacement, possibly by replacing an expensive 4 year college degree with something closer to mentoring or apprenticeship.

How did your brother measure the number of hours a student works, especially retroactively after a lifetime of work?

What hours are these? Outside job, or hours at a desk studying?

Link?

Needs definition at best. At worst the data gathering technique of measuring “hours worked” after measuring “lifetime income” appear suspect.

“Coaching?” We don’t need any new sports related terms — why not stick with “tutoring” and the almost forgotten “teaching”. Don’t or didn’t the top English Universities assign students to tutors? And do we really need a Professor of Economics and Public Policy to discover that online classes and text messaging are no match for teaching — with a real live teacher — in a class size small enough that some kind of personal relationship might exist between the teacher and students?

“Policymakers and academics share growing concerns about stagnating college completion rates and negative student experiences.” That statement and the rest of that paragraph says far more to me than the rest of this post. The measures for educational effectiveness are “completion rate” and “student experiences”? What kind of measures are those for education — at least what the word once meant? What concerns do “policymakers” and “academics” have about education — ROI? And I have trouble equating “academics” with “teachers”. In my long ago college experience — I was impressed by how little most of the professors — particularly the “academics” were concerned with students or teaching. Academics worried about landing research grants and gathering talented graduate students to work in their labs. Undergraduate teaching duties were considered a necessary but distasteful drag on their real work as professors. The rest of the paragraph outlines what I read as students feeling a deep apathy toward and/or dissatisfaction with our so-called higher education — not unlike the American abstainers’/voters’ feelings of apathy toward and/or dissatisfaction with what remains of our political process as described in today’s links.

The rest of this post reads like a preliminary market study for some new coaching service for higher education — like the ones which help high school students prep for entrance exams. “Education” has devolved to mere acquisition of certification for one of the increasingly limited slots in the meritocracy.

Actually many profs also try to influence the brighter students to go to grad school (particularly in STEM), as they need to insure a continuous supply of folks at the front end of the graduate process.

Thanks Lambert, not surpising that a one-time message didn’t do much to help individual students clarify goals and purpose for attending university. Regarding the year-long project it’s hard to tell what “academic advice” is. Probably a mixture of general tips and when possible help with specific content.

Peer tutoring is expanding at my institution, wouldn’t surprise me if the leadership is hoping for the benefits reported here – better grades leading to more academic success. Completed degrees is a critical measure for intitutional success. Among other things leadership may hope that a little investment will have more than a little return. Tutors generally get some training and a modest hourly rate. Paired with a campaign to strengthen student/institutional identification such a project could have a lot more than a little return. A windfall especially for private institutions that charge 50k or more per year.

Maybe TPTB aren’t interested in creating conditions that help large numbers of students succeed? Just a thought.

Yes, well, as others have pointed out this used to be the job of “tutors”, and the whole article just seems a complicated way of saying that there’s no substitute for face to face contact to motivate students. (The same problem notoriously arises with distance learning).

But when I was young going to university was a privilege, and you were even paid a tiny grant by the government. In these days of universities as factories for producing mass education, a lot of students, in my experience, don’t know why they are there, except that threats and promises related to their economic futures have driven them there. Not only are we treating students like customers, we mislead them about what they are buying. No wonder they are confused.

I doubt this will be posted as I seem to have triggered some sort of filter but…

The problem that is skipped over in all discussions of this sort is the fact the absolutely everyone in the world, with a disturbing degree of desperation, feels the need to go to college or else…..

If you don’t go to college you are cursed for all time to live a life of poverty or maybe if you really struggle, just above.

That and the fact that the degree doesn’t seem to change that reality seems to evade discussion.