Yves here. This post reinforces a point we’ve made regularly: that US businessmen and policymakers are degrading the quality of the US workforce by pushing so many entry level jobs, which was how skilled workers learned their tradecraft, overseas. This has been pervasive in computer science, a field of supposed US leadership, for over a decade. It’s becoming more widespread in the law and accounting, where tasks like legal research and writing briefs are increasingly farmed out to India. Senior managers in IT firms have said foreign staffing (whether sent offshore or done by H-1B visa workers) always requires more bodies and still almost without exception yields inferior results, but no one seems willing or able to buck a bad new normal.

This behavior is bizarre given that neoliberalism fetishizes “competitiveness” at a country level. But it makes sense in the case of the US since the country is run to serve multinationals and the top 0.1%, and not domestic interests.

However, a sour note is the use of the term “market” later. This is neoliberal virtue signaling for a process that wasn’t a market in any normal sense. Companies used to be willing to train people, and wanting/needing to recoup their investment meant they had incentives to treat their employees well enough that most of the good ones would stay around for a few years so they’d recoup their investment. There really was a time when most businesses were sincere when they said, “Our people are our biggest asset.” In fact, back in the day, if you changed jobs too often (as in more frequently than every 8-10 years), employers assumed you had a performance or personality problem unless you had a good story as to why you had switched.

And a personal note: my paternal grandfather was one of the very last journeymen trained in the US, right before World War I. Production tasks were broken down during the war to allow for more rapid hiring and training to accommodate increased war output needs. As a result, my grandfather got a battlefield promotion and was almost immediately made a supervisor. He later ran a machine shop and taught manufacturing at night at Pratt Institute. Ironically, most of his students were professionals, like lawyers and accountants, who needed to know a bit about how job shops and light manufacturing worked to do their jobs better.

By David de la Croix, Professor at Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium, Matthias Doepke, Professor of Economics, Northwestern University and Joel Mokyr, Professor of Economics, Northwestern University. Originally published at VoxEU

The role of specific institutions was important in giving Europe a technological advantage well before the Industrial Revolution. This column argues that apprenticeships were crucial to Europe’s rise. Unlike in the extended families or clans in other parts of the world, apprentices in Europe’s guild systems could learn from any master. New techniques and innovations could thus spread rapidly across the continent, without being constrained by family lines.

The ‘Great Enrichment’ that Europe experienced after the Industrial Revolution remains a central question in economic history (McCloskey 2016). It is now well established that the European economies’ technological head-start over the rest of world did not start strictly with the Industrial Revolution in the middle of the 18th century, but had already begun with the great transformations of the late 15th and 16th centuries (Broadberry 2015). Yet the exact causes of this growth are still very much in doubt. Clearly, the effect of science properly speaking on economic growth before the 18th century is still limited at best. Yet it would be unwarranted to dismiss the role of knowledge and its dissemination through Europe. In recent work, we argue that efficient institutions for organising apprenticeship provided a crucial foundation for the rise of Europe (de la Croix et al. 2016).

Tacit Knowledge and the Central Role of Apprenticeship

Before the Industrial Revolution, almost all useful knowledge was tacit. The main mechanism through which tacit skills were transmitted across generations was apprenticeship, a relationship linking a skilled adult to a youngster whom he taught the trade. Apprentices spent most of their waking hours in the master’s workshop, where they learned from the master and more experienced apprentices and journeymen. As apprentices spent time in the shop, they gradually acquired the skills of the master, often through imitation and guided learning-by-doing (DeMunck and Soly 2007, Steffens 2001). In Figure 1, a 14th century illustration from a dye-shop attests to the medieval origins of the institution, while a 19th century painting by Louis-Emile Adan, “Man and boy making shoes”, illustrates its persistence into the modern era. Apprenticeship was the primary mechanism by which productive human capital was created in the past.

Figure 1 Evidence of the persistence of apprenticeship-based learning in Europe

Differences in the rates of technological progress may in principle have two different sources: differences in the rate of original innovation, and differences in the speed of the dissemination of existing ideas. Our theoretical analysis focuses entirely on the second channel and abstracts from differences in the rate of invention. What we argue is that the institutions governing the intergenerational transmission mechanism were of central importance to the dissemination of best-practice techniques. The nature of the apprenticeship system based on personal contacts and mostly local networks was a central factor in the closing of gaps between best-practice and average-practice techniques. We argue that apprenticeship institutions in Europe led to faster dissemination of best-practice technical knowledge and contributed, ultimately, to Europe’s technological primacy.

The Need for Apprenticeship Institutions

To see why apprenticeship institutions mattered so much, it should be recognised that the contract between master and apprentice was in many ways deficient and incomplete. The master promised to teach his young student the secrets of the trade, in exchange for labour services provided by the apprentice and, at times, a lump sum premium paid by the youngster’s parents or guardian. Yet the exact nature of the skills transferred could never be fully specified in the contract, nor could the diligence and loyalty shown by the apprentice in carrying out his side of the deal. Because of these moral hazard problems, some institution that enforced the contract and arbitrated disputes when they arose was crucial.

In our analysis, we focus on the apprenticeship system and abstract from other diffusion mechanisms. We distinguish between four types of historically relevant apprenticeship institutions: (nuclear) families, clans, guilds, and markets. In the nuclear family, fathers taught their sons, and hence knowledge was passed only through vertical transmission. In the family equilibrium, the moral hazard problem was resolved (assuming the father to be sufficiently altruistic) but no knowledge was transferred across families, so that the rate of technological progress was very slow. In much of the non-European world, extended families or clans were the fundamental unit of economic organisation among artisans. In this world, the apprentice could learn not just from his father but also from other relatives, depending on the size of the clan. In our model, the clan solved the moral hazard problem because within the clan, people trusted each other and had strong incentives to avoid opportunistic behaviour. Apprentices could learn from any clan members in their chosen trade (and thus could do better than just learning from their fathers). Yet because the clan was limited to people who were related to one another and eventually shared a common ancestor, the diffusion of technology was faster than in a family, but not as fast as when apprentices could learn from the entire population of masters in his town.

Efficient Apprenticeship Institutions: Guilds and Markets

A third form of contract enforcement is through the guilds. In Europe, where craft guilds appeared in the middle ages, the guild enforced apprenticeship contracts, mediated between masters and apprenticeship, and prevented the worst excesses of opportunistic behaviour. The enforcement of contracts and the orderly intergenerational transmission of skills has been cited often by those who have sought to rehabilitate the guilds, traditionally depicted as technologically conservative rent-seeking institutions (Epstein 2008, 2013). Yet historically, the evidence that guilds tried to limit entry into their trade – for instance, by limiting the number of apprentices that each master could take (Trivellato 2008) – is quite strong (Ogilvie 2014). Thus, the diffusion of technology in the guild system was faster than the family or the clan equilibrium, but not as fast as it could be. Still, in the guild system the apprentices could learn from any master. New techniques and innovations could thus spread rapidly across Europe, without being constrained by family lines. The dissemination of ideas was further promoted by institutions such as ‘journeymanship’ (also regulated by guilds), in which apprentices travelled from town to town after their initial training to learn (or in some cases teach) new techniques.

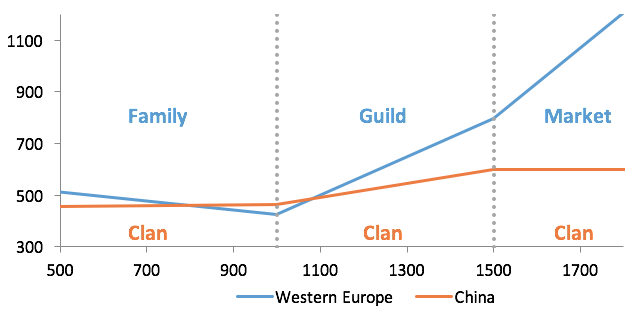

The most efficient institution was one we call ‘market equilibrium’, in which apprentices were free to move about and learn from the best masters (either as apprentices or journeymen), and the most efficient techniques thus disseminated the fastest, without being constrained by the anti-competitive aspect of guilds. The question then arises of how the participants in such market equilibria overcame opportunistic behaviour. The answer is in part that third-party enforcement became increasingly a reality in some parts of Europe, but also that reputation mechanisms assured that cheating by either side would be costly. An illustration of the significance of the four regimes in relation to the rise of Western Europe (relative to the previous leader, China) is provided in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Income per capita in Western Europe and China

Source: Maddison (2010).

The four forms of contract-enforcement appeared in many economies side-by-side, but in late medieval and early modern Europe, the guild and market equilibria became increasingly dominant. Thus, the areas that had the most effective apprenticeship institutions were the ones that developed the most progressive and innovative workmanship and experienced the most technological progress even in the absence of major breakthroughs. A recent example is watchmaking in 18th century Britain, where watches became continuously cheaper and better (Kelly and Ó Gráda 2016). But in almost any artisanal trade in Europe – from textiles and ironworking to millwrights and shipbuilding – we observe substantial progress between 1500 and 1750, and knowledge that diffused relatively rapidly (Berg 2007). Some historians have coined the term ‘mindful hand’ to characterise the growing sophistication of the top-of-the-line artisans of the age (Roberts and Schaffer 2007).

It is not surprising, then, that in economies in which apprenticeship was unconstrained and regulated by markets so that knowledge could cross kinship lines, the level of artisanal skills blossomed. This is particularly true for England, where guilds had already been weakened and where the famous 1562 Statute of Artificers, which regulated the parameters of apprenticeship, was widely circumvented (Wallis 2008), but it was also true for the Netherlands (Davids 2003, 2007), the richest economy in Europe for centuries.

Apprenticeship and the Industrial Revolution

A high level of technical competence, as sustained by effective apprenticeship institutions, played a crucial role in the Industrial Revolution. We argue that they were not a sufficient condition for economic growth: on its own, artisanal progress without the infusion of novel radical insights from more formal knowledge would have run into diminishing returns. Still, these institutions might well have been a necessary condition for the take-off. But without the workmanship that could turn blueprints and new designs into working machines and that could scale up models, the insights of the giants of the Industrial Revolution would have been as economically inconsequential as Da Vinci’s brilliant technological sketches. English ironmasters such as John Wilkinson were indispensable if inventors such as James Watt and Samuel Crompton were to turn their ideas into reality and bring about the Industrial Revolution. The French economist Jean-Baptiste Say said it best in 1803: “the enormous wealth of Britain is less owing to her own advances in scientific acquirements … as to the wonderful practical skills of her adventurers (entrepreneurs) in the useful application of knowledge and the superiority of her workmen” (Say 1821, vol. 1). After 1815, British skilled mechanics and technicians swarmed all over the Continent to install and maintain the new machinery. They had been trained through a superior system of apprenticeship.

Outside Europe, the institutions of apprenticeship were far less effective. Kinship relations still dominated many other economies, especially China (Greif and Tabellini 2017). While guilds existed in the Ottoman world, India, and in China, we have found no evidence that they did much more than secure exclusionary rents by prohibiting non-members from entering their industries. Apprenticeship remained largely a family or sectarian affair. This is not to deny that kinship relations remained important in Western Europe as well – but in economic history, degree is everything. Recent work trying to understand the Industrial Revolution and the Great Enrichment that followed it has increasingly focused on upper-tail human capital (Mokyr 2009, Squicciarini and Voigtländer 2015, de la Croix and Licandro 2015). In that story, the human capital of top-level artisans and the way it was produced played a larger role than has been realised so far.

One lesson that our work drives home is that the sharp distinction between ‘institutions’ and human capital, as elements in economic growth (Glaeser et al. 2004), is historically inappropriate. Institutions determined the quantity and quality of human capital formation in past societies, and the nature of these institutions help explain the miraculous enrichment of Europe after the Industrial Revolution.

Summary and Significance

One of Western Europe’s core historical features was its reliance on mechanisms and institutions that were not based on kinship relations. When applied to learning institutions, this feature led to the adoption of superior apprenticeship institutions, and thus promoted a fast diffusion of best techniques, and it allowed Western Europe to gain primacy in the centuries leading up to the Industrial Revolution. Tacit knowledge and skills remain relevant in today’s economy. For example, master-apprentice-like relationships are still common in the education of doctors and scientists, and the continuing system of formal apprenticeship in Germany is often credited as one source of the country’s low youth unemployment and general economic success.

One of the great advances in understanding our economic past in the past decades has been that “institutions matter” — but identifying which institutions mattered, what they did, and why they arose in the first place has been a matter of considerable controversy. The institutions governing the intergenerational transmission of skills and tacit knowledge should definitely be part of that narrative.

See original post for references

Think about it from the company’s perspective though. Why go through all that hassle to train an employee when that person will leave or be poached by a competitor? Especially when there’s a glut of quality labour available.

It is just not a US problem. Knowledge based work is in a funk here in Europe and is in need of a Renaissance – badly. Skills are so ‘challenged’ I regularly recruit ‘outsiders’ to fill posts. European schools (and corporations because they don’t spend much on training) are failing their students ‘bigly’ and is having an adverse impact on business. I see folks with advanced degrees – copy-paste content without regard to coherence – unable to articulate core functions and worst of all, fail to take responsibility for improving professional skills. No passion.

Bring back the guilds. Quick!

The ease of getting advanced degrees shows the efficiency of IT – what used to be complicated, time-consuming and only the bright could do is now done by anyone and everyone who knows how to use the copy and paste commands.

Human capital (horrible phrase) is now more advanced than ever, yet, the generation coming out into the work-place is not much (if any) more talented and educated than previous ones.

The cry of retraining is needed is mostly about warehousing people, the for profit education providers know this and are making a killing in profits. For every cry for tax-payers has to pay for retraining of displaced workers there is a crony-capitalist in the ‘business’ of education jumping for joy.

But with the credentialism we’re now seeing and experiencing could it be any different?

People will do what they have to do to get a job, if a couple of years of copying and pasting is needed then that is what will be done.

I’d rather have work more evenly distributed, then there would be less need for degrees but reducing working time to share the work is according to the capitalists and their unwitting allies the work-fetishists apparently impossible….

“reducing working time to share the work is according to the capitalists and their unwitting allies the work-fetishists apparently impossible….”

I imagine it’s that concept of “sharing” that they just can’t grasp…

Spending any resources on expendable employees is un-economic. First you have to decide that employees aren’t “deplorables”. This is a globalism and class war.

Pretty much, one has to cherry pick what people are available, the idea of starting with a young person and developing them, is so 1950s.

In Europe you have the additional problem that unions are too good at protecting older workers.

Is that such a terrible problem to have?

Good question. Depends on circumstances. Doesn’t matter if there are plenty of jobs for young people. Unions in the US are different, they are all quislings working for The Man.

This is an interesting rate-of-dissemination hypothesis and supporting evidence for the technological edge gained by Europeans before and during the industrial revolution.

It is also interesting that population growth accelerated both in Europe and Asia starting in the 1st half of the 18th century (it was much higher than in other continents) but although growth was faster in Asia I think that it was much more spatially concentrated in Europe. So arguably having lots of people very close to each other helped disseminate techniques through the open model of apprenticeship -rather than through the slower kinship model- in Europe.

The findings also are politically correct because they put the emphasis on the rate of dissemination rather than on the rate of origination, the latter having politically unsavory implications (hint: genetics).

My company has been around a long time but the region has gone from predominately White European with the associated values and work ethic to blacks and Arabs. There simply is not an adequate supply of young people who are worth taking the time to train anymore. Good people are moving away and we certainly can’t convince a young person to move here for the training. The region is only getting worse. There’s no point moving since it’s the same everywhere. Starting over overseas with a modern and much more automated process is the only option that is viable.

What you need is to get a group of similar employers (perhaps including competitors of yours) and the local community college together to craft a pre-apprenticeship program. They do a good job of identifying kids with a good work ethic who would be happy to make a career in manufacturing. My guess is that there are more of these kids around than you think but that they have no idea it is actually possible to still make a career in mfg. Especially if you are in a declining area.

The problem is the newly predominately black and Arab culture. There are a few kids that could do it but the critical mass isn’t there to make it sustainable. Believe me, we’ve looked at everything to make it work. We are in retreat. It’s the same in so many other areas here and throughout Europe. Wisconsin’s urban areas are effecitively seceded and lost.

Since opposition to taxes has gutted public education, it’s no surprise that educated people are no longer available. The companies suffering now helped to make the bed they’re lying in.

Let’s be a little bit honest. The main problem isn’t the education but the human capital it has to work with.

The Hajnal Line may also help explain somewhat the economic and dissemination differences in Europe. It may be instructive to overlay that on the guild and industrializing countries. Here is another reference, too.

A few comments on this interesting article.

1) When talking about a systematic, well-established apprenticeship system the talk is always about Germany. Austria, Switzerland and I believe the Netherlands all have a comparably strong and popular apprenticeship system.

2) The article enthuses about the “market-based” approach to apprenticeship, where people move freely between masters and employers, thus acquiring and disseminating best practices.

This is a gross simplification. In fact, in many trades craftsmen and specialized workers were prohibited from doing that — precisely when and where the so-called “market-oriented” apprenticeship system was supposed to be in full swing.

Typical examples are:

a) Murano glass makers were prohibited upon severe punishment from leaving the Venetian Republic. Emigration was risky (manufacturing secrets were to be preserved at any cost) and basically meant never coming back.

b) Artisans knowledgeable in manufacturing porcelain or comparable products (which preceded or competed the re-invention of porcelain in Europe) were basically under house arrest in the various manufactures established in the 18th century by various European princes, especially German ones.

c) British engineers were forbidden, by an act of Parliament, to exercise their profession outside the realm of the kingdom. The law was enacted at the dawn of the 1st industrial revolution and was in force till the early 19th century.

So much for the freedom of movement in “market-oriented” British, German and Northern Italian regions.

3) From the mid-19th century onwards, firm owners and governments imposed various mechanisms to bind more strongly specialized workers to the firms’ activities:

a) proper work contracts requiring the worker to notify in advance his resignation (before then, this was a “work at will” system where a worker could leave from one day to the other);

b) compulsory employment booklet (checked by the police; its absence, or gaps in employment would immediately deem their owner as a vagrant, to be arrested);

c) work certificates (another requirement to get a proper work contract — no certificates for previous work would make things difficult).

These were especially stringent in Germanic countries — exactly those where the apprenticeship system was, and remains strong.

All this to show that I do not quite buy the “development through fluid labour market” of the article. Things were decidedly more involved.

One context that we have lost is slowness. In the early years of guild-industry communication was slow compared to now. Invention was incremental. Today there’s nothing very organic about pockets of invention – they either are kept hidden and patented as industrial secrets or they explode into the market. It occurs to me that we have created an almost impossibly complex market which we try to treat as simple and easy to use/do. Any apprenticeship today would not take an apprentice through all the steps of the enterprise – but just the minimum needed to function efficiently – automation does all the work. There are no layers of understanding. Probably because to achieve it would take an incredible amount of time. And by then the factory could well be obsolete.

I know this is a historical article but the lack of mention of labor unions in a story about the decline of apprenticeship strikes me as odd. In the U.S. at least, the only long-lasting apprenticeship programs in the 20th century were union-negotiated. A few are even still around.

There are still apprenticeship programs for electricians, and also I believe for masons, but I recall reading a good number of years ago already that brick masons were finding relatively few young people willing to submit themselves to the demands of a seven-year apprenticeship. Perhaps we also need to look at whether what apprenticeships we have are designed so that there are at least adequate wages throughout, and so that the future rewards may be seen to be worth the long commitment. (Have there not been reports that more and more electricians are getting stuck working for big companies that may never pay them very well? That is my impression locally, and I thought I had read something last year, maybe here.) Are any readers here involved in building trades or other skilled work that still can be learned by formal apprenticeship? I always welcome input from people with experience.

We have the perfect president then. He has publicly demonstrated how to develop apprentices over 14 TV seasons. Everyone should take note and follow his example.

(Sorry, couldn’t help myself.)

Props to your paternal grandfather! Unfortunately, machinists and machine shops are disappearing in the US much to our detriment.

Many of our public high schools are starting to change their messaging. No longer just for students to matriculate and be only “college ready”, but now to be both “college and career ready.”

I teach six periods of architecture and engineering in a public high school as a Career Technical Education (CTE) instructor. If you would recall the vocational shop classes of old, but now proactively integrate these: academic rigor, partnerships with local businesses, providing both career and professional guidance, externships and internship opportunities, plus teaching soft skills like building effective teams for collaboration, project management, along with participation in Career Teacher Student Organizations, and the lists of standards that must be adhered too, yes it’s a monumental task. But CTE is real and it’s growing, funded by Federal dollars via the Perkins Act.

My CTE colleagues and I all had long standing professional careers in the private sector, but have felt a calling back to the classroom. We bring with us years of real world professional experience to our nations young people. In my discipline area students get to hear stories of the corporate boardroom, the politics between municipal stakeholders and communities, plus learn about the process and application of architecture, civil and structural engineering, landscape architecture and urban planning.

It’s not an apprenticeship but the CTE programs require a two year sequence. Now students have opportunities to experience hands on real world relevance. I’ve seen it work, opens up a whole world of possibilities that otherwise would have been hidden.

Prior to becoming a CTE teacher I was an ACE Mentor (Architecture, Construction Engineering) for four years in an inner city school. Not just model building competitions we know the truth that not all kids are college bound, nor should they be, so we’d introduce them to the trades, trade schools and unions. Those students with real aptitude got our hearty recommendations, got internships and they working now.

Apprenticeships are not dead, but they’re evolving, as fast as the technology in the crafts. Next year I’ll have 3D printers and we’ll start studies in Addiditive Manufacturing. Other CTE programs have students working with genomics and gene synthesizers, another aviation.

So long as public funds remain available School districts would do well to get out of old thinking and support CTE with concerted efforts to hire the professionals they can and build up thus great opportunity and transition into the professional and career world for this next generation.

I am troubled by the lack of data here. We get one graph and two works of art. A couple of thoughts on the topic: The Black Plague is supposed to have increased the status of working people by eliminating so many of them. (Remember that it wasn’t a one time thing. There were periodic attacks of plague.) What effect did that have on artisans and the transmission of knowledge? After 1492 an astounding flood of wealth came into Europe, first into Spain and then into other countries, where the Spanish spent their money. What effect did this have? I don’t know enough about China to compare it to Europe and we are given no detail. For a long time Chinese technology was far ahead of European technology, as was Indian and Arab technology, I think. When did this change and why?

A stiff theoretical framework, too, in the pigeonholes of family (nuclear), clan, guild, and market. I can’t imagine a village, if the blacksmith’s children all died of diphtheria, that would decide that they were doomed to live, someday, without a blacksmith. Little societies have ways of trusting that aren’t tied to bloodlines. How much this matters to the broader argument, I do not know.