By David Autor, Ford Professor and Associate Head, MIT Department of Economics; David Dorn, Chair of International Trade and Labor Markets, University of Zurich; Gordon Hanson, Pacific Economic Cooperation Chair in International Economic Relations and Director of the Center on Emerging and Pacific Economies, UC San Diego; Gary P. Pisano, Harry E. Figgie Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School; and Pian Shu, Visiting scholar, MIT Sloan School of Management; Assistant Professor, Harvard Business School. Originally published at VoxEU

The decline of the US manufacturing sector played such a prominent topic in the 2016 presidential election campaign that New York Times journalist Binyamin Appelbaum wondered in a headline “Why Are Politicians So Obsessed With Manufacturing?” (Appelbaum 2016). Much of the concern about the health of the manufacturing sector derives from the observation that its employment level is near historic lows. Ever since the end of the Great Recession, the sector has employed fewer than 12.5 million workers – the lowest job count in manufacturing since the US entered WWII in 1941. Manufacturing lost almost 6 million jobs during the 2000s alone, and strikingly, most of this decline came before the onset of the Great Recession.

Despite the poor employment performance in the 2000s, however, value added in manufacturing has been growing as fast as the overall US economy. Its share of US GDP remained stable, an achievement matched by few other high-income economies over the same period (Moran and Oldenski 2014). While the extraordinary growth of value added in the computer and semiconductor industries masks a more sluggish performance in other manufacturing industries (Houseman et al. 2014), the sector’s output growth clearly exceeds its employment growth.

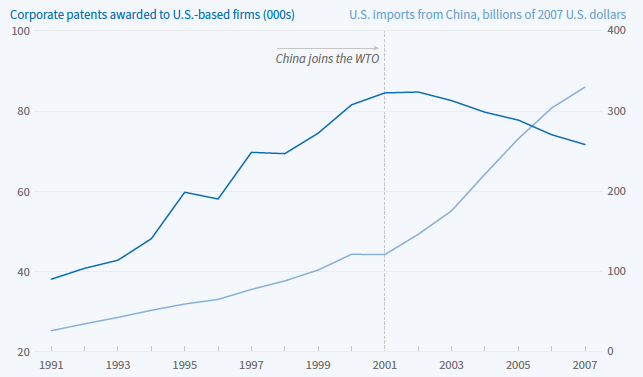

Another metric for the health of the US manufacturing sector, which has been less present in the recent debate, is its production of innovation as measured by patents. Manufacturing is the locus of US innovation and accounts for more than two thirds of US R&D spending (Helper et al. 2012) and for a similarly large share of US patents. Figure 1 shows that the annual number of patents awarded to US-based firms (dated by the year of patent application) doubled from less than 40,000 in 1991 to more than 80,000 in 2001, but subsequently declined through 2007.

Figure 1 US innovation and imports from China

Source: Maas (2017) based on authors’ calculations using the U.S. Patent and Inventor Database and the UN Comtrade Database.

During the 1990s, and especially the 2000s, the US manufacturing sector was exposed to a rapid surge in import competition from China. Figure 1 shows that imports from China increased more than tenfold between 1991 and 2007. Most of that growth occurred after China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, which coincides with the trend reversal in US patent production. The Chinese export boom was triggered by a series of economic reforms that included the establishment of Special Economic Zones for the production of export goods, and an easing of restrictions that had hindered firms’ access to labour, capital, and technology. The emergence of China as the world’s leading exporter of manufactured goods has been a major competitive shock for manufacturing firms in the US and elsewhere (Autor et al. 2016).

Although a now substantial literature evaluates the impact of China’s rise on labour market outcomes such as industry employment (Pierce and Schott 2015, Acemoglu et al. 2016) and workers’ earnings (Autor et al. 2014), far less is known about the impact of trade on innovative activities in US firms and industries. The effect of more intensive product-market competition on innovation is theoretically ambiguous. In standard oligopoly models, greater product market competition lowers profits and reduces incentives to invest in innovation. However, greater competition may also induce more innovation, either if pre-innovation rents fall relative to expected post-innovation rents (Agion et al. 2005), or if firms redeploy slack factors from goods production to innovation activities as competition depresses the demand for the firms’ products (Bloom et al. 2014). Indeed, a European study finds that firms in several European countries innovate more when Chinese imports increase in their industries, even as their employment level falls (Bloom et al. 2016).

In a recent paper, we analyse the impact of Chinese import competition on innovation in the US (Autor et al. 2016). Our analysis draws on all US corporate patents with application dates from 1975 to 2007 that are granted by March 2013. To obtain more information about the firms that applied for these patents, we use the firm names indicated on the patents to match them to firm data from Standard & Poor’s Compustat database. One challenge in this matching process is that patent records often contain different versions, abbreviations, and (mis-)spellings of a firm’s name, so that the names on patents do not correspond exactly to those in the firm database. We overcome this problem by constructing a novel matching algorithm that leverages the capabilities of an internet search engine. In a first step, we enter every firm name string that appears in the patent or Compustat data into the bing.com search engine, and we collect the URLs of the top five search results. We assign a patent to a Compustat firm if the corresponding firm name strings lead to at least two common URLs. This fully automated procedure builds on the web search engines’ capability to detect a company homepage or other webpages relating it even if the firm name’s is abbreviated or misspelled. Overall, we match almost three quarters of all corporate patents to Compustat, which covers companies listed on US stock markets.

The overall growth in corporate patents shown in Figure 1 masks important heterogeneity in patenting trends for the two sectors that contribute the most to overall US patent output. The computer and electronics sector increased its share in overall US patents from 10% in 1975 to 35% in 2007, and accounted for almost all the growth during the 1990s seen in Figure 1. By contrast, the chemical and petroleum sector’s contribution to US patent output fell from 27% in 1975 to 10% in 2007, as the number of annual patents from this sector declined over time. Both the growth in computer patents and the decline in chemicals patents began well prior to the surge of Chinese exports in the 1990s. This observation is important because import competition from China hit the computer sector much more than the chemical industry, yet it would be erroneous to attribute the superior innovation performance of the computer sector to its greater import exposure, given that the acceleration in patenting in that sector predates the exposure to China trade.

The central finding of our regression analysis is that firms whose industries were exposed to a greater surge of Chinese import competition from 1991 to 2007 experienced a significant decline in their patent output. A one standard deviation larger increase in import penetration decreased a firm’s patent output by 15 percentage points. Using data from the 1975 to 1991 period and a regression setup that accounts for the diverging secular innovation trends in computers and chemical, we confirm that firms in China-exposed industries did not already have a weaker patent growth prior to the arrival of the competing imports.

The firm data allow us to embed the patent analysis in a wider context of other indicators for the activities of firms. Importantly, we find that import competition not only reduced patenting but also firms’ R&D expenditures. Import-competing firms further experienced declines in global sales, employment, capital stock, and stock market value. They were more likely to suffer a decline in operating profits.

The innovation activity of US firms did not merely shift from the US to other countries. We estimate similar negative effects of import competition on patents by US firms’ domestic employees and by their foreign employees. Instead, our results are most consistent with the notion that the rapid and large increase in competition squeezed firms’ profitability and forced them to downsize along many margins, including innovation. Consistent with that interpretation, we find that the adverse impact of import competition on patent output was concentrated in firms that were already initially more indebted and less profitable.

The decline of innovation in the face of Chinese import competition suggest that R&D and manufacturing tend to be complements rather than substitutes. That is, when faced with rapidly intensifying rivalry in the manufacturing stage of industry production, firms tend not to substitute effort from production to R&D. While politicians’ ‘obsession’ with manufacturing is primarily due to the sizable employment losses in the sector during recent decades, an accompanying reduction in innovation may well affect economic growth in the longer term.

See original post for references

I am wary of anyone measuring “innovation” by number of patents issued. Since the Internet came of age in the 90s the technology sector has been spinning its wheels and going nowhere.

@RangerRick, +1 on the spinning wheels with no progress. Somehow, it would seem obvious that reducing US workforces and hiring Chinese and Indian replacements overseas would reduce the number of people “innovating” (dreaming up patents, useful or not).

Yeah the more i look at tech history it seems to basically be about coasting on Moore’s Law (an observation made by Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, about the size of transistors on a integrated circuit being halved roughly every 2 years), and more recently li-ion battery technology.

Because if you look at what the internals of a smartphone do today, it is basically the same as what the big mainframes did back when the internet was first conceived.

Damn it, the web browser has basically become the modern leased terminal.

That’s a very fair assessment (and a good amount of ideas aren’t patented – rather they become ‘trade secrets’). But by all accounts, R&D spending intensity has declined recently and the R&D productivity has decreased. Each new idea seems to require more resources than the last one.

Agreed. Particularly since China is issuing enormous numbers of patents across all sectors, not just manufacturing.

It is a clear response to ongoing US use of patents to protect multinational corporate monopolies.

I am wary of anyone measuring “innovation” by number of patents issued.

indeed, an interesting chart would be the diversity of the manufacturing entities associated with the patents.

I specualte much of the growth of patents are from a diminishing diversity o firms — those in the biotech, pharma, and semiconductor industries filing patents intended to inhibit competition and real innovation .

I would also speculate that much real innovation that does exist in manufacturing, certainly in chemical process industry, are focused on improved efficiency and “know how”, are treated as trade secrets rather than being published in patents.

And how many of those patents are filed, just to keep older patents from expiring, such as with the drug indistry? Or how Monsanto patens geane sequences?

Patents are stupid things.

Interestingly enough, here we for whatever reason buck the trend. Software engineers are “atta-boy’d”* when they come up with patents but aren’t pressured at all and the subject hardly comes up. Meanwhile the mechanical engineers I think need to come up with at least one a year.

And man are they..again, stupid – that’s not my opinion, that’s an opinion on his own portfolio from a guy that has a lot of patents. Nobody is inventing the next transistor, the suspension bridge or anything even close to that sort of advancement.

It is another make-work program for lawyers.

*not just verbal there is money involved… comically, it is given as another reason why s/w is paid more than h/w which is paid more than mechanical… the s/w guys “don’t get a lot of patent money”….

PS: sorry that rant wasn’t meant to take away from the base message of the article, which I agree with: The Chinese make things and they then learn way more than somebody sitting in a lab scribbling thoughts down ever could.

Where manufacturing goes, the innovation follows.

That’s because there’s a lot of innovation that follows manufacturing.

– Producer’s goods

– Robotics and automation (Making robots and such equipment is very high tech work)

– Material science

– Process improvements

It also produces demand for a lot of high skilled workers and in turn, can command high wages. That can feed other things, like universities.

I bet if you were to take a graph of China, you’d see the exact opposite trend. Export surplus and patents. Sure patents are not a perfect way to measure, but there are other trends:

– China’s volume of scientific papers has gotten better

– Quality of scientific paper not up to Western levels, but growing

See here:

http://www.nature.com/news/china-by-the-numbers-1.20122

A big part of the problem is America’s cut of Blue Skies Research – part of the quarterly profit situation.

The very rich really screwed us over when they outsourced jobs.

Yeah the constant thinking around patents etc is that of “thought factories”, basically about piling a bunch of people into a building and have them dream up new widgets and services constantly.

Sorry but that’s not how it works. New thought comes from having intimate relations with old thoughts. In IT this means having practical interaction with existing computing systems. This enable one to see ways to refine and simplify what already exist.

Your argument is cogent.

Interestingly, it reminds me of very similar discussions more than two decades ago, when some researchers were wondering why the “natural” shift from manufacturing to services was linked to an apparent stagnation of productivity. One of the instantiations of that discussion was “productivity of IT manufacturing is increasing fast, but productivity of service sectors massively using IT is stagnating; how come?”

A proposed explanation was that genuine innovation, resulting in productivity improvements, is closely linked to a healthy manufacturing sector.

What would be interesting is a comparison with countries whose industrial sector, though competing with China, has remained vigorous — Germany, Switzerland, Japan, South Korea.

Or conversely, our model of innovation, McDonalds University. Creative geniuses lay around on bean bag chairs listening to Phish jams on their Bluetooth connected headphones, visualizing Better Macs, deeper fried Freedom Fries, rainbow colored soda water and an even happier, more kid friendly, Ronald McDonald?

Entirely agree, Altandmain. And this is far from a recently identified issue. Recall former Intel CEO Andy Grove presciently articulated the long-term negative effects on innovation stemming from the transfer of U.S. manufacturing many years ago.

https://www.cnet.com/au/news/intels-andy-grove-on-manufacturing-in-america/

“…rapid surge in import competition from China.”

This is a bit misleading in that it implies that Chinese products were “competing” against US goods. The competition was in ridiculously cheap tooling and fabrication, criminally low labor, and zero environmental considerations.

As an industrial designer during that period we watched it all getting outsourced. Even when I had high-end tooling requirements and dealt with German companies which were the best, I found out that they too were outsourcing to China.

Industrial design was the last to be outsourced and we didn’t go quietly.

Interesting.

I thought you were going to make the point that much of this “competition” was make-outsource decisions made WITHIN firms, not competition between US firms and Chinese firms.

Yes lefty, does this not seem to be the main fallacy here?

Firstly US competition with China is not as framed in the article, but importantly mainly consists of US firms outsourcing, not US firms competing with Chinese firms. I think this phase will come but we are not there yet.

The consequence of this is that US firms can increase profits without R&D, and hence there is less motivation to spend on R&D.

What about the glass for Apple’s IPhones, which was a bona fide innovation?

If I read the conclusion correctly, the point is not that U.S. firms moved patent production overseas with manufacturing but that they abandoned R&D when they moved manufacturing. This sounds right to me. OTOH, I think they are missing something by only cross-checking patents with publicly held companies. My guess is that private-equity owned manufacturing would have cut R&D even more. It would have been fruitful for them to compare the two.

Jane Jacobs’ Cities and the Wealth of Nations focuses on her ideal of cities as generators of innovative growth. Vital cities, for her, are places to go to meet people you’ve never met before, doing things that have never been done before. The book seeks to study the economics of vitality.

To find the boundary, it also studies non-vitality. One kind of non-vital region Jacobs calls “transplant regions”. An enterprise that is being invented relies on the city’s variety to do all kinds of things that need doing that aren’t foreseen; it depends on a metaphorical root structure for finance, personnel, supplies, technical help, and all sorts of other things. Once the innovation is done, it’s different. The enterprise can be commoditized, and packed up along with a vertical stack of inputs, outputs, services, and business relationships. Then it can be picked up an transplanted just about anywhere. Maybe there are simple requirements like available electrical power, or bulk transportation, but nothing like the web of connections needed for innovation.

Following this idea, we could speculate that that China began industrial competition with the U.S. using factories transplanted from the U.S. The tricky patent generation had already been done, and it was a matter of putting the package down on the ground, building a road, plugging in the power, installing a bunch of workers, and letting it run. Those factories could be transplanted because they no longer needed nor encouraged innovation.

So whence all this Chinese innovation? I don’t know. Novelty? Excitement? Simply being there when some innovation becomes obviously necessary has got to be part of it. As I said before, I’m disappointed: “What causes creativity? We don’t know.”

The Chinese are moving up the value chain.

It’s no different than say Japan. Japan for example dominates the world when it comes to robotics.

Right now the US is losing that edge of being on the bleeding edge. Eventually, China will follow Japan and become the source of first mover advantage.

South Korea and Taiwan have followed a very similar path upwards.

While Dr. Autor brings up some things to think about, he really needs to remember that correlation is not causation, and he should have addressed some other problems with the issuance of patents, none of which have to do with China.

1. The issuance of overly broad patents and patent trolling which inhibits and severely raises the cost for anyone trying to get a new patent. How has that affected the amount of new patents approved?

2. When the dot.com industry failed (they were a great source of new patents), did the number of patents also drop? It appears so from his graph, but appearances can be misleading.

3. When a little company comes out with something new they would like to patent, they are either bought out or economically killed off and their patent never sees the light of day, especially if the new patent could compete with a corporate process that is making money. This one is hard to quantify, but everyone I know has an anecdote about an innovative new company that was pushed out of business by the “big boys”, particularly in the computer industry and pharmaceuticals……

It would be really interesting to see the numbers for how we damaged our own patent system and then compare it to China’s influence….

The Dutch pharmaceutical company, Crucell, comes to mind. Profitable, and from what I can tell, a good corporate citizen. Their thing was vaccines and if there was a possible health crisis in say, Aceh, after the tsunami, they would donate vaccines to help.

They had an immortalized human cell line that they started renting out for research, and many big companies, Merck, etc, were using it. I don’t fully understand the collegiality involved but there was apparently some sharing of data in utilizing this cell line. Best of All, they were going after some pesky and not necessarily big money pathogens,–like TB, which 20% of the world’s population is carrying, but for which there is no effective vaccine.(Yes, BCG, but I said effective.) They were doing clinical trials in South Africa with patients who were co-infected with HIV and TB. The clincher was when they started working on developing an influenza vaccine that targeted the part of the virus that does not change from year to year. This would mean that you would be vaccinated against the flu the same way as hepatitis B. A series of two or three shots and you would be immune to the flu, period. I think this threatened to break some big rice bowls because Johnson & Johnson stepped in and bought them and, as far as I can tell, they sank like a stone. Disclaimer:

Since I started following this company, around 2003, many paywalls have gone up, so I can’t verify what exactly happened after the purchase.

Novel business strategy: Do the right thing, and get bought out by the larger evil-doer…

My opinion is different. I don’t think manufacturing has quelled innovation as much as consolidation across all industries to a few mega corporations. That, combined with fees & regulations, makes it all but impossible for even the smartest and well connected to open businesses in areas other than software (which is why Silicon Valley startups are 90% software these days).

It took me 7 years to finally open up a nanotech manufacturing firm, and I had quite a bit of financial backing, 5 PhD’s, 2 JD’s and more. I was lucky to go to a top school and lucky enough to have a wife that excelled in academia for years gathering various talents & connections. For the average person, opening up a restaurant is hard enough these days, let alone a new tech business. Machines are literally a third of the price in China, steel is anywhere from 1/20 to 1/5 the price, there are probably a thousand small factories that can make you a PCB on the cheap even at lower volumes. Everything left in America is ether ultra-high end, or ultra-high volume, both which contain immense capital costs. We are talking 10’s of millions with uncertain payoff’s as margins continue to plummet.

A friend of mine recently closed down his business as the products he was selling were becoming commoditized and he saw the writing on the wall. An average lathe machinist cost him around $200/hr in overhead. Its $50 in China (but China’s wages are rising – maybe the future will see an equilibrium). The molds he sold to the aerospace industry kept getting crunched by Chinese and Korean competitors. 10 years ago, even though prices were cheap in China and Korea, their manufacturing capabilities for tight tolerance products, like aerospace and automotive, were relatively bad. Nowadays, with all the capital having moved to Asia, their factories are often times newer, cleaner, more well equipped, and overstaffed compared to ours. If you’ve seen Ford’s manufacturing facilities in China vs the US you’d understand. Its night and day.

However, the above case is not one of innovation, but rather, one of commoditization. Also, lack of patents isn’t suprising. When everything is made in China and sold abroad, most companies forego patents in all but the most needed cases (usually, biotech, pharma, military).

“We use the firm names indicated on the patents to match them to firm data from S&P’s Compustat database. One challenge in this matching process is that patent records often contain different versions, abbreviations, and (mis-)spellings of a firm’s name, so that the names on patents do not correspond exactly to those in the firm database.”

Compustat is an absolute horror to use, even for big, prominent companies that are or were constituents of the large-cap S&P 500 index.

After a corporate acquisition, Compustat’s practice (malpractice, actually) is to retroactively, anachronistically modify records from all previous years with the acquirer’s name, instead of the contemporaneous corporate name. Beyond that, Compustat also introduces its own unauthorized abbreviations, which can render valid, complete corporate names unretrievable by Compustat’s dimwitted search engine.

As a particularly absurd example, Compustat shows a tiny San Antonio based company called Cattlesale as an S&P 500 index constituent in 1991. That’s ridiculous. After hours of sleuthing, I finally found an obscure news article indicating that Cattlesale had bought a building once owned by Datapoint, a computer hardware manufacturer which was an S&P 500 member in 1991.

In this example, patents filed by Datapoint are not going to matched to Compustat records using the authors’ quick ‘n dirty procedure of utilizing the top five search results. Compustat’s poisoned database is an intricate mess which takes hundreds of hours of review, research and correction by hand to produce usable, error-free data. Thus I doubt the validity of the authors’ conclusions,

Innovation will follow the factory floor simply because product and process development is a physical, iterative, hands on process and proximity matters. The beancounters cannot simply throw paperwork over the wall (or the Pacific) and it somehow gets done right.

I have a question about ‘value added’ in manufacturing.

Suppose an American corporation ships some raw materials to Elbonia to be converted into intermediate products, and say 1000 total person-hours of labor are applied to these materials, and the total value of the finished intermediate products is say $1000. Then these are shipped to the United States, and one worker spends one hour bolting these parts together and the on-paper value added is $9000. But wouldn’t that be missing the point? Can’t these numbers be manipulated by vertically integrated corporations or corporations with tight relationships with overseas suppliers?

Wouldn’t it be better to count not the nominal dollar value added by a stage in a manufacturing process, but simply the person-hours of labor at each stage?

But wouldn’t that be missing the point? Can’t these numbers be manipulated by vertically integrated corporations or corporations with tight relationships with overseas suppliers?

Yes the numbers can be manipulated but it’s worse than that: they don’t need to be manipulated to give misleading results. The data are anonymized so there isn’t that much incentive for any particular co to go out of their way to massage them. But since the primary objective is to book profit in low-tax locations, there is also no need or desire to construct a second set of “more accurate” accounts.

When you get into the weeds, there are issues with all the various ways to measure value-added when it comes to trying to allocate shares within a corporation to particular locations.

I was recently spending a few days by Venice Beach in LA. One morning during our walk along the water we came across a vintage car show. What a good time looking at all those vintage cars that had been lovingly restored. To think that there was, not that long ago, a world of American design that was unique and inspiring. Granted that in terms of efficiency and mechanical soundness most of those 1950s behemoths wouldn’t measure up to the ugly Hyundai, Kias, and (alack) Chevrolets that make our streets and parking spaces paeans to the drab. But when daring-in-design was ended so was mechanical innovation, with American car companies only innovating when they had to play catch up with the imports.

But it wasn’t the Japanese, Koreans and Germans who did in Detroit. It was Detroit itself, with a huge boost from Wall Street which dictated consolidation and ever increasing emphasis on marketing over innovation and design.

Those cars, at least the the looks, were probably sculpted by designers in California. The internal mechanical bits are global.

How this article and conversation can occur without mention of the work of Ralph Gomory is beyond me. He headed up R&D for IBM, is a brilliant mathmeticion and economist.

http://m.huffpost.com/us/entry/3567196

That is a great article by Gomery! (“On Manufacturing and Innovation”) Thanks for the link.

Here’s an excerpt (but do read the whole thing, it’s not too long):

I second TheCatSaid’s sentiments. A great article that should be required reading for every economist every time before they utter one word from their throne at the policy table. That was written four years ago and since then things have gotten progressively worse.

In Canada, and no doubt the US has a similar program, there are tax credits available for scientific research and experimental development, called SRED. This program is completely abused by multinational corporations whereby product development is funded by Canadian taxpayers and the resulting production of those products is transferred to China.

Here is the relevant section from Ralph’s article.

This discussion of innovation has things fundamentally backwards. It does not make sense to talk about innovation as if innovation was an end in itself. We could innovate until the cows come home and if we can’t translate that innovation into something substantial that adds to the economic output of the United States, it does little for America. If our strategy is to generate new ideas that other countries acquire, either as the foundation of a new industry or to gain an advantage in an old one, we will have the expense and glory of being innovators, and they will have the resulting industries and the economic benefits.

We are taxed through the back door by our governments to assist the Chinese elite in their quest to build their manufacturing capacity and to then loot the wealth generated by the Chinese peasants for themselves, and subsequently the looted money is used to buy up and drive up the price of housing in Vancouver and Toronto. Depending on whether you are Canadian peasant or a Chinese elite, it’s either a vicious or virtuous circle.

Politicians in democracies are, as a class, narcissistic lawyers. They are completely clueless when it comes to discussions of innovation and productivity and the general field of manufacturing. For the most part, they think of themselves as innovative when the raise their hourly rate from $400 to $600. To them, it’s great that their Toronto or Vancouver home has skyrocketed in price due to Chinese elite making a big splash with loot, and Canadian peasants be damned.

Globalization is a disaster. Ecologic and economic.

Competition from China will encourage Innovation here. Isn’t that a basic tenet of the Market?

But Innovation is a red-herring like Education — like worker-pay tied to Labor productivity numbers. Why should the payment to Labor be tied to labor’s contribution to the gain any more than the payment to the entrepreneur’s contribution — whose contribution is far more difficult to attribute? Why so privilege that “position”? How might I measure “Competition from China” and “Innovation in the US” and relate those numbers that I might conclude “Competition from China reduced Innovation”? I’m perfectly happy to accept that conclusion — but less than perfectly willing to view this Post’s analysis as explanatory no matter the finding. China as competitor — I believe that may be a short-lived honor — with China next replaced by lowest “total cost” country ‘X’.

I do believe Innovation declined. Innovation is not truly valued in America and has not been valued for some time now — outside from it’s rhetorical value.

1) Not all patents are equal. They are a poor metric in the context of this post.

2) Many patents have little or no genuine innovative value (even if they were granted and supposedly met the novelty requirement).

3) Many patents are only defensive patents, designed to block competition, or patents of small-entity inventors are bought out (or stolen) by large entities, often just to ensure that something newer and better never sees the light of day. (US government does that, too.)

4) The value of patents (or their worthlessness) has to be evaluated in context of their commercial environment–e.g., is a particular sector in an early stage, or already in a death spiral?

5) The value of patents also has to be evaluated in terms of its potential value for other sectors and applications than those referred to in the patent.

I’m grateful to M-CAM’s generosity in opening my eyes to how patents can be considered in more in-depth ways. (They have developed a lot of in-house linguistic analysis tools which allows them to evaluate patents and Intellectual Property in various creative ways.) David E. Martin has some interesting interviews on the internet about Intellectual Property, innovation, and related topics.

Another important point not mentioned in the original post, is that many of the most impactful innovations in the last 50+ years were the result of US government funding of the R&D in question and of subsequent commercial development.

Much of the image of the lone, valiant inventor/entrepreneur is a myth and does not reflect the reality of the immense “breaks”, “luck”, overt support, and covert support (helping hands and even guiding hands behind the scenes).

There have been wonderful creative innovators and some have deserved their success. Many more have been abused or taken advantage of by the system. It would be a mistake to think the famous successes are an accurate reflection of markets, novelty, commercial potential or the most deserving social benefit. We are encouraged to innovate and are promised rewards, but the current system does not function as a meritocracy.

I wonder about the impact of demographics… if average age of patent seeker was around 40 then the 2001 peak would fit with the boomer demographic bulge.

From what I have read, patent seeker age has been dropping since somewhere in 90s (tech influence?) so the drop in patents after 2001 would fit with the demographics… baby bust after the boomer bulge.

Patent numbers would only be one variable among many to analyze the change in innovation…

Prof based in MIT;but apparently has not stepped outside Boston area. North East was first rust belt. Midwest labor benefited from manufacturing job loss in NE! That rust belt is still festering. That isi why 41% of CT voters voted for Trump! Midwest lost to low wage Southern labor.

Hey why did South not upgrade its workforce???? Shamed by even Singapore!

See:

http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/top_performers/2016/01/the_low-wage_strategy_continues_in_the_south_is_it_the_future_for_your_state.html

The Low-Wage Strategy in the South: Is It the Future for Your State?

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/ushistory2ay/chapter/deindustrialization-and-the-rise-of-the-sunbelt-2/

Deindustrialization and the Rise of the Sunbelt

Did not effect Germany!

https://hbr.org/2014/05/why-germany-dominates-the-u-s-in-innovation

Why Germany Dominates the U.S. in Innovation

“Germany owes its robust economy of recent years in part to the success of its manufacturing sector, from basic materials to tools on the factory floor.

The reason Germany has remained competitive against cheaper manufacturers in Asia and elsewhere is that it has made good use of new technology.

The Fraunhofer network of technical institutes is an example of how researchers and manufacturers work closely together in industry.

The Germans have excelled in old industries such as automobiles and are building centers of excellence in biotechnology and other emerging areas.”

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/us-could-learn-germany-high-tech-manufacturing/

Companies have also stopped investing in innovation because it is a “cost”. Check out Clayton Christensen. That’s why universities do majority of research now;and most grad students in STEM subjects in US are foreign! many of them are CHINESE!

New York Times journalist Binyamin Appelbaum wondered in a headline “Why Are Politicians So Obsessed With Manufacturing?” — Because simply sitting astride money flows and taking a cut, as most “industries” in the NYT’s hometown do, creates no actual wealth and requires you to parasitize someone else’s actual wealth creation? I suppose if you’re like Applebaum and live in an elite coastal financial bubble economy such a notion might well seem otherworldly. And the fact that far too few pols are honestly “obsessed With manufacturing” explains much of the real-economic hollowing-out which helped give us President Trump by way of backlash. Mr. Applebaum is a perfect illustration of Upton Sinclair’s famous “It’s hard to get a man to understand…” aphorism.

Thanks also for the great Ralph Gomory piece, Glen!

Morons that cant tell a cult when they see one surely will not recognize a long con.

.

Any excuse to get up and look down on your fellow American supported by gangs and confidence games built on dirty filthy rags of prejudice and a totally corrupt prison system.

.

I prefer that we would indulge in more industry and less excuses to be kind.

.

We all want the same things.