By Chris Dillow, an economics writer at the Investors Chronicle. He blogs at Stumbling and Mumbling and is the author of New Labour and the end of Politics. Cross-posted from Evonomics.

Chris Edwards says the privatizations started by Thatcher “transformed the British economy” and boosted productivity. This raises an under-appreciated paradox.

The thing is that privatization isn’t the only thing to have happened since the 1980s which should have raised productivity, according to (what I’ll loosely call) neoliberal ideology. Trades unions have weakened, which should have reduced “restrictive practices”. Managers have become better paid, which should have attracted more skilful ones, and better incentivized them to increase productivity. And the workforce has more human capital: since the mid-80s, the proportion of workers with a degree has quadrupled from 8% to one-third.

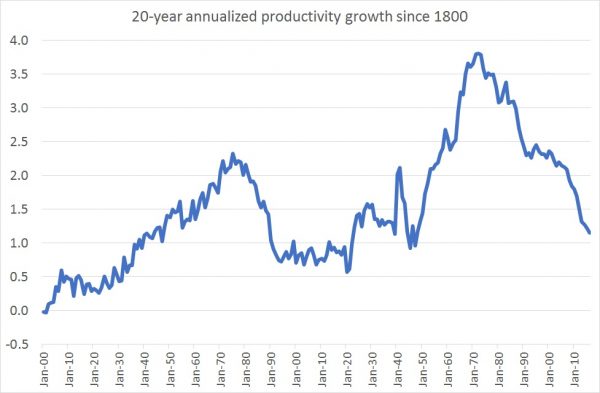

Neoliberal ideology, then, predicts that productivity growth should have accelerated. But it hasn’t. In fact, Bank of England data show that productivity growth, averaged over 20 years, has trended down since the 1970s.

Why?

It could be that neoliberal reforms did give a short-lived boost to productivity. I’m not sure. As Dietz Vollrath says, economies are usually slow to respond to a rise in potential output. If there had been a big rise in potential output, therefore, it should show up in the data on 20-year growth. It hasn’t.

Another possibility is that the productivity-enhancing effects of neoliberalism have been outweighed by the forces of secular stagnation – the dearth of innovations and profitable investment projects.

But there’s another possibility – that neoliberalism has in fact contributed to the productivity slowdown.

I’m thinking of three different ways in which this is possible.

One works through macroeconomic policy. In tight labour markets of the sort we had in the post-war years, employers had an incentive to raise productivity because they couldn’t so easily reply upon suppressing wages to raise profits. Also, confidence that aggregate demand would remain high encouraged firms to invest and so raise capital-labour ratios. In the post-social democracy years, these spurs to productivity have been weaker.

Another mechanism is that inequality can reduce productivity. For example, it generates (pdf) distrust which depresses growth by worsening the quality of policy; exacerbating “markets for lemons” problems; and by diverting resources towards low-productivity guard labour.

A third mechanism is that neoliberal management itself can reduce productivity. There are several pathways here:

– Good management can be bad for investment and innovation. William Nordhaus has shown that the profits from innovation are small. And Charles Lee and Salman Arif have shown that capital spending is often motivated by sentiment rather than by cold-minded appraisal with the result that it often leads to falling profits. We can interpret the slowdowns in innovation and investment as evidence that bosses have wised up to these facts. Also, an emphasis upon cost-effectiveness, routine and best practice can deny employees the space and time to experiment and innovate. Either way, Joseph Schumpeter’s point seems valid: capitalist growth requires a buccaneering spirit which is killed off by rational bureaucracy.

– As Jeffrey Nielsen has argued, “rank-based” organizations can demotivate more junior staff, who expect to be told what to do rather than use their initiative.

– The high-powered incentives offered to bosses can backfire. They can incentivize rent-seeking, office politics and jockeying for the top job rather than getting on with one’s work. They can crowd out intrinsic motivations such as professional pride. And they can divert (pdf) managers towards doing tasks that are easily monitored rather than ones which are important to an organization but harder to measure: for example, cost-cutting can be monitored and incentivized but maintaining a healthy corporate culture is less easily measured and so can be neglected by crude incentive schemes.

– Empowering management can increase opposition to change. As McAfee and Brynjolfsson have shown, reaping the benefits of technical change often requires organizational change. But well-paid bosses have little reason to want to rock the boat by undertaking such change. The upshot is that we are stuck in what van Ark calls (pdf) the “installation phase” of the digital economy rather than the deployment phase. As Joel Mokyr has said, the forces of conservatism eventually suppress technical creativity.

All this is consistent with the Big Fact – that aggregate productivity growth has been lower in the neoliberal era than it was in the 1945-73 heyday of social democracy.

I’ll concede that this is only suggestive and that there might be another possibility – that the strong growth in productivity in the post-war period was an aberration caused by firms catching up and taking advantage of pre-war innovations. This, though, still leaves us with the possibility that slow growth is a feature of normal capitalism.

I thought the drama was financial growth supplanted productive growth w/ equities being the main culprit i.e. short term fixation for a myriad of profit taking games in the near term and not long term….

disheveled… entire nations are geared to service this paradigm….

I think it’s the landlords and real estate speculators who have done much better than the capital/equity class the last few decades. For example, over the past 10 years many Int’l Stock funds are essentially flat after reinvesting any dividends, notwithstanding an annual 2-3% dividend rate. This means the underlying stock prices actually went down over the last 10 years during the latest Raging Bull market. Part of this flatness/decline of (primarily) European/Asian stock prices is likely partly due to US$ currency appreciation compared to the Euro, Pound Sterling, Yen and Yuan, but still.

Wall Street likely makes plenty of money funding big landlords and property developers in the largest coastal cities (and churning over rising government debt pays a pretty penny too), so they’ve been doing fine. But when a large segment of the general populace is paying ~40% of their income for rent (or a home mortgage financed by Wall Street), and ~40% of their total income for various federal, state and local taxes, the current situation seems more akin to neo-feudalism than any dominance by equity companies that actually produce goods and services that sustain jobs and grow the “real” economy. If we’re working 4 out of 5 days just to put a roof over our heads and pay governments their due, something doesn’t seem right, but I’m not sure it’s the fault of “equities.”

Fair points to both skippy and Robert Frances. I think the bubblicious behavior in equity markets and in real estate markets are both symptoms of financialization sucking up capital around the world. There are obviously varying circumstances at different locations, but there’s lots of money out there bidding up prices on existing assets, but doing little to create new productive assets (which is much more risky than leveraging up). I think that ties in with short-termism.

Toll booths everywhere the eye can see. And yes, the financial sector is the biggest one of them all. Not the only one, but the biggest. These toll booths have caused the cost of producing anything of value to explode. The financial sector does it by extracting interest charges out of profit, and by vastly inflating asset prices. On the books of the borrower, it’s debit cash and credit interest-bearing debt. On the books of the bank is where it really gets interesting — debit toll both receivable for doing nothing of value, and credit fictitious liability to never be repaid. Then the bank collects on the toll booth receivable until the profits from the underlying productive assets run dry. Once they run dry, you have what they call a liquidity crisis, which provides banks with the unique opportunity to pass the fictitious liabilities to never be repaid on to the Fed, where they remain in hiding so that a new ponzi scheme can started by the banks. That in a nutshell is neoliberal economics…where increases in productivity are swallowed whole by these neoliberal toll booths.

Have you looked at Michael Hudson’s work? Rent-seeking seems to be key. Also, I’m surprised you don’t mention off-shoring vs. wages. Didn’t wage stagnation in the US start in the 70s?

It’s the money, honey.

Pay crappy wages, make them work crappy hours, then cut the hours, send factories away, cut benefits, cut retirement… maybe workers are stressed, worrying about the mortgage, their kids, unaffordable healthcare, food, where the next hit is coming from…

Happy workers not stressed over the next deadline might think how could I do something faster, easier, with less input. As it is they wonder how they’ll get thru the day… or night.

Host is getting killed.

In the end the suited class do not want to talk about how the “consumer” (that word, ugh…) is also the worker.

So to consume, one first have to work and be paid a livable wage. That one can spend to buy the goods one are supposed to consume.

Not denigrating this article, but the work of E. Ray Canterbery, Michael Hudson, Michael Perelman, Steve Keen, etc., explains it better.

The main phrase and goal behind everything:

inflating financial assets (1980: 7 trillion, 2015: 200 trillion)

Recommended Reading:

Wall Street Capitalism: The Theory of the Bondholding Class, by E. Ray Canterbery

Wealth, Power and the Crisis in Laissez-Faire Capitalism, by Donald Gibson

The Case for the Corporate Death Penalty by Mary Kreiner Ramirez and Steven A. Ramirez

Open Secret by Erin Arvedlund

Extreme Money by Satyajit Das

Treasure Islands by Nicholas Shaxson

Killing the Host by Michael Hudson

Web of Debt by Ellen Brown

The Invention of Capitalism by Michael Perelman

Over a hundred years ago, Thorstein Veblen was onto this neoliberal game as well. Suggest reading his “The Theory of Business Enterprise” as well.

Interesting: the graph suggests that the “Information Revolution” had little positive contribution to productivity growth. Just a little blip in the 90s. Which probably means we can not rely on advances in technology to help. And the opposite may dominate: increasingly complex technology systems degrade productivity (fragility, cost, diminishing returns, …).

dotcom was not productive and GPD is not vectored….

And yet financiers still believe in unicorns.

I wonder why?

Doug Henwood covered this extensively in his book After the New Economy. I would recommend reading it, but this blog post summarizes part of that argument regarding the IT lead productivity growth:

https://lbo-news.com/2015/02/09/the-productivity-slowdown-is-structural-stagnation-our-fate/

I don’t know that I agree with complex technology degrading technology, that seems hard to prove at this point. But what does seem the case is that dominant technology players are either rent extractors that hold back technological advance (Verizon, Comcast, etc) or are leveraging technology in ways that contribute nothing to productivity at all. Google has transformed advertising and gobbled up the lions share of it. Facebook is a close competitor and only provides entertainment value. Netflix leverages technology so we can watch more TV. Uber loses money as we’ve seen and simply replaced taxi dispatchers. The game as always is to capture a monopoly in some capital rich segment of society, whatever that is. That does not increase productivity but rather shifts winners and losers using IT.

Great quote. That in a nutshell is why capitalism will destroy itself. Far easier and more profitable to extract wealth from others than it is to actually innovate and create it.

Oh, look, it peaked in 1971.

Since productivity is measured as output (IN DOLLARS) per capita…maybe it’s the yardstick being used that changed?

Let’s imagine labor input was constant. IF HOWEVER THE MONEY NO LONGER IS RETAINING ITS VALUE/ABILITY TO STORE LABOR, then the amount of labor stored per unit of money goes down. So even if input labor was declining (fancy gizmos, PCs etc), the currency’s ability to store labor was declining even faster.

What changed in 1971? Not much, they just closed the gold window.

Money no longer requires work to produce, so it’s no longer useful as a reliable way to store (or measure) work.

https://medium.com/@_Maverick_/energy-money-and-the-destruction-of-equilibrium-da96f8a225d6#.ufk6jxoph

Sorta hard to take your leap of faith when the GD was a gold slandered failure…

Money doesn’t “store labor”, it’s a token with value attributed to it by human beings. It may command a certain amount of labor from others because humans agree to attribute value to it, but that’s as far as it goes. Your point is a little muddy so you may wish to rephrase or clarify.

Similarly when we retire we hope the economy in the future produces enough goods and services that we can command some of them with whatever financial instruments we have stockpiled. That’s very different than, say, stockpiling the actual food and medicine we intend to consume and putting them in a physical warehouse. These are abstractions. It’s important not to lose sight of the reality.

A great point, and, I think, directly related to understanding that money is merely a claim on the consumption of natural resources, which, of course, sustain life. BTW: What also occurred in 1970 was the peak -Hubbert’s Peak”- of domestic extraction of light sweet crude oil in the USA.

yes and people – meaning economists! – don’t realize that fracking is so different in so many ways (including the specific end product) that even if we ever produce as much “oil” as in 1970 it may well be comparing apples to kumquats.

Yes, gone are the days that you could strike oil just by shootin’ at some food.

Read Jessica M. Leppler’s The Many Panics of 1837 for an excellent picture of how gold-backed money was used. Unfortunately, under the gold system all the work in the world couldn’t produce money. All that could produce it was gold.

On second reading, the picture I’m forming is:

* Jackson’s government chartered a lot of new banks in western states and moved gold to them to finance development on the frontier.

* London bankers saw gold leaving the Bank of the United States (which acted somewhat like a central bank, although CBs didn’t strictly exist then) and feared for the stability of the American financial system, AND, anticipating a need to re-invest their own gold in Caribbean economies which were ceasing to use slave labor, London reduced support (i.e. gold) for American finance.

* Everybody stifled each other.

The big problem with a Gold System is lack of money when it’s needed, and just the fear of lack of money can bring everything down.

[Commenting system is still broken. Symptom is that I submit a comment on the “Neoliberalism…” page, and the next thing I know, I’m reading the Links page. The comment never seems to show up.]

Also worth remembering: Jackson paid the entire U.S. national “debt” in 1835.

See Randall Wray for more.

Per Leppler, Jackson had a honkin’ huge budget surplus from selling land to pioneers. I haven’t discovered yet where the pioneers got the money. I’ll check the Wray link.

Everybody mentions the “panics” and “crises” under a gold system. The difference? The crises ended, usually pretty quickly. The system rebalances because it has to. We’re starting Year 9 of the current panic, and the system is still on life support. Check out Target 2 balances in Europe, or the BOJ’s balance sheet, or the ridiculous stock market, the only transmission channel they have left. Check out velocity. Just because you hide the problem doesn’t mean you solved the problem. What do you do with a debt-based money system when everyone is stuffed to the gills with debt already that they can only service with rates at or below zero? Turn the dial to “11” and issue more? With $1.2 T in student debt and 50% in arrears? With $200B in permanent monthly life support purchases by CBs? And since when are CBs just glorified hedge funds? You never grow your way out either because all that debt brought all that demand forward to the present, and now the past.

And it’s not as though gold is perfect: it’s just better than anything else that has ever been tried. Nobody “imposed” the gold system, it was arrived at through trial and error over centuries, very painful error with outcomes that were uniformly always the same.

‘Nobody “imposed” the gold system’

Whereas the fiat system WAS imposed — first stealthily, as the Federal Reserve gradually made government securities the bulk of its balance sheet during 1941-1971; then by arbitrary presidential decree on a summer Sunday night.

What AFAT (All Fiat, All the Time) has given us is sequential bubbles of larger and larger amplitude. Look at a stock market chart over the past quarter century and you’ll see what I mean. Escalating bubbles are the economic analogue to the forced resonance failure of the Tacoma Narrows bridge in 1940.

Bubble III now underway is looking like the Mother of All Bubbles. Every important central bank on the planet is in on it, having QE’d their balance sheets by multiples of five times and more.

Unlike when Johnny Law’s Mississippi Bubble went down in 1720, affecting mainly one country (France), this time a global population of 7 billion has bet the entire planetary economy on Bubble III. When Bubble III goes down, it’s going to be life altering — cities on flame with rock ‘n roll.

In a chastened post-Bubble world, the old yellow dog might actually get a second look as a credible alternative to disgraced central bankers, some of whom are likely to end up suspended from gibbets for their crimes against the people.

Expect the Federal Reserve Act to be repealed, and counterfeiting laws to be extended to government officials just the same as homebrew currency forgers. Emitting irredeemable currency is a serious crime. Traditionally it was a capital crime.

The “everything floats against everything else” craziness after Bretton Woods and the Plaza Accord fell apart is incredibly dysfunctional.

A micro example is Azerbaijan right now, business activity is grinding to a halt. Why? Because of two devaluations totaling 50% in the last 12 months. How would a businessman possibly know whether a deal was worth doing? When? Wait, or get ahead of the next devaluation? How would you ever know the investment hurdle rate?

Multiply by 10,000 and you get our current world economy. All you can do is stare at the chimney on the central bank

churchheadquarters and see what color smoke is coming out. Did High Priestess Janet say “may” or “might”?As Travis Bickle said “someday a REAL rain is gonna come and wash away all the scum…”

Anybody advocating the gold standard should review US recession history:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_recessions_in_the_United_States

looking at the period since 1836, the gold standard era, basically ending in 1933, was far worse recessions/depressions versus anything seen since. They lasted twice as long then, GDP declined nearly 5x as much, and happened twice as often. 25 months of growth on average between recession then, 84 since.

Fabulous for the wealthy clever enough to not loan out all their wealth, they could pick up real assets for a song every four years.*

Fiat means banks don’t fail and depositors don’t lose their money. Beyond that we don’t take advantage of the system, worse for us… homeowners could have been kept in their homes this last time. And we could be fixing infra while employing the millions in their parents basements.

We’re not where we could be, we’re not where we should be, but thank god we’re not where we used to be.

* “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate.” That, according to Herbert Hoover, was the advice he received from Andrew Mellon, the Treasury secretary, as America plunged into depression. To be fair, there’s some question about whether Mellon actually said that; all we have is Hoover’s version, written many years later.

It doesn’t rebalance here we would want it to, necessarily, it just rebalances somewhere, based on circumstance, and the whims of the people who have the gold. That is taken to be right because There Is No Alternative.

Re debt, the Michael Hudson talk linked lately from that symposium on religion is very interesting.

I think you’re onto something here, but misfiring a bit.

I think the dismantling of the Keynesian system of fixed exchange rates among developed countries was a big event and possibly underrated in its effects on the world economy.

Floating exchange rates and corresponding/connected to that was interest rate volatility. These two factors were variables starting in the 1970s whereas previously they hadn’t been an issue for managers to worry about. Foreign exchange derivatives and interest rate derivatives were the main culprits in the nascent growth of derivative markets. This really opened doors for big finance to insert itself into the business model of big multinational companies.

Clearly, there’s no net gains for society and productivity to have these derivative markets, but there’s lots of opportunities for banks to eat your lunch if you’re a multinational with a lot at risk due to changes in inflation, interest rates, or exchange rates.

Forex derivatives — the largest derivatives market by volume — are a perfect example of a productivity-subtracting casino. All of those traders, all over the planet, are dedicating their time to a zero-sum game that adds nothing to human living standards.

This immense waste of human talent is the legacy of the elastic currency theorists, whose destructive game has been underway for 45 years now. One should retain a healthy skepticism that their failed system will reach its 50th anniversary.

QE was the final declaration that the fiateers have lost control. Now they are just hunkered down, as the Bubble III express train thunders toward a broken trestle.

And the USA went off the gold standard in the year . . . .

Having millions of underemployed graduates and individuals in general means that you have pervasive waste and gross mismanagement of resources throughout the entire system.

An economy of broken dreams and windows. You can show GDP holding up but at what cost?

@Moneta…

I showed you a long time ago that even the author of the metric of GDP took exception to its totalitarian use, never meant to be a standalone, just an optic to consider in the great scope of things.

disheveled… file under when people get religion about stuff….

Maybe I’d understand better if you did not speak in tongues.

We all know GDP is a bad measure, yet it’s still the standard.

We all know it’s a failed metric, yet neoliberalism is failing by it’s own standards of measurement. That really drives the point home.

I’d be careful about banding about speaking in tongues with your past, unless you want me to drag old baggage up…

disheveled…. point stands… the author said GDP was mis-attributed…

The other issue is that our growth keeps on relying on an increasing amount of resources and energy.

While EREOI has dropped, energy is still quite plentiful and cheap because we keep on subsidizing it through all kinds of monetary and fiscal policies.

Since we are not measuring the quality of GDP nor linking it to the real physical world, we can expect more dire results as we keep on growing the energetic needs of our system while EREOI keeps on declining.

Now that I have turned 70, I seem to be spending more time at the doctors’ (nothing serious). EVERY procedure requires filling out the same forms, with the same old info,, a blizzard of paper. gallons of printer ink, etc., etc…………..

I see the same pattern, though not as serious, at businesses. I often wonder at the profit margin when I purchase a nut or a bolt and am given a multi-part computer generated invoice that must have cost the business 25 cents for the form.

And then there are the tedious, mind-numbing Power-Point presentations……………

It seems that data processing has become the tail wagging the dog, with an army of back office bureaucrats figuring out new ways to do what are in fact NON-PRODUCTIVE tasks simply because computers make it easy.

We could learn from France, where every citizen carries an encrypted smart card with their complete medical records recorded and updated at every doctor’s or pharmacy visit.

Learning from France: I believe the encrypted smart card providing instant access to one’s complete medical records is common to many countries. Despite differences in the details of their systems, all of them share what we lack: universal health care.

Until we can prioritize certain human rights over various corporate rights, our health care non-system will continue to victimize the population with sub-standard care, outrageously high costs to individuals and the society at large, and the terrible results one might expect from that corrupt combination.

“We could learn from France”:

We could learn from Kaiser Permanente, which provides patients not only passive downloadable access to their medical records (e.g., diagnostic images, records of allergies, immunizations, future appointments, diagnoses, instructions from past visits, and laboratory results), but through its HealthConnectOnline, patients can actively book appointments, reorder prescriptions, and communicate with healthcare professionals by email.

Health leaders from forty-three countries (including Brazil, Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, and the United Kingdom) have studied Kaiser’s integrated health care delivery system and its high-tech capabilities, which not only allow patients to access their medical records but enable it to conduct research to develop and share best clinical practices. http://kaiserpermanentehistory.org/tag/kaiser-permanente-international/ (Full disclosure: I have been a KP member for fifty years; my wife is a retired KP doc.)

I can’t help thinking of all the expertise companies throw away when they do their yearly RIFs to make quarterly numbers. At my workplace, a software company, there are 5 year old platforms we can’t maintain or expand because the people who made them were fired, or they were contractors who moved on immediately after their contracts ended. No wonder most IT projects fail. I’m very aware my employer has zero investment in me and that my years of experience make me next in line to be laid off. I wish I had more of a reason to care. It seems like companies hire young and naive workers who don’t understand how this works: but the eager attitudes disappear after the next round of layoffs.

When did layoffs gain popularity as a management practice? In manufacturing it began in the 70s. White collar workers weren’t really hit until the recession in the early 90s.

Occurs to me that the multiples of compensation given to people near the top of orgs relative to the bottom of the hierarchy leads them to believe they actually add value in similar multiples of those at the bottom, and therefore to deeply discount the contributions made by more junior members. Having some self-knowledge about their own talents and applying such a discount, they conclude that the rank and file barely achieve sentience and are truly interchangeable.

Management also does not seem to be concerned that a recurring layoff policy tends to limit cooperative behavior while people are still employed.

This is evidenced by current employees preserving key knowledge to themselves in an attempt to be viewed as “indispensable” in their current tasks.

This is perfectly understandable when the workforce is made uncertain of their job security, unique institutional knowledge may be personally internally hoarded rather than shared with new employees.

Okay, this is anecdotal, but in my experience, most managers have no idea of how to increase productivity. It’s the people on the line, doing the work, who see the places where problems exist and who come up with inventive solutions to those problems that increase the amount of work accomplished in a given unit of time. The driver of productivity, I would suggest, is the inherent sloth of the workers, who want to get the biggest bang for the least effort.

Of course, this doesn’t apply to all workers, but it applies to enough of them.

Now, if you suppress wages for workers, and managers get better paid, where are all those talented and inventive people going to go? Into management. And, while they may be talented and inventive, they won’t know enough about the work process to see the problem areas or be able to come up with productivity enhancing solutions to those problems that won’t disrupt the rest of the process. Instead you get big schemes and radical new changes — which may improve productivity, but only at the cost of massive disruption, assuming they actually work. There is no steady, incremental improvement.

So, I would suggest a fourth possible reason: managers getting significantly better paid. Despite the Randian mythology of the genius manager who can do every job in the production process better than the drones they employ, most managers only know how to manage. The way the actual work is done might as well be magic as far as they are concerned.

Oh, and the idea that better pay attracts more skilled people? All I know is that whenever anyone complained about the shortage of STEM workers, any suggestion that raising the pay of such workers would attract more talented people to the field (rather than having them go into, say, finance) was routinely rejected with condescending explanations about how you can’t solve such a shortage by throwing money at it. Apparently, higher pay only works to attract better people when dealing with management; it doesn’t work anywhere else in the economy.

I was recently in the middle of a major work upheaval, resulting directly from managerial instructions to change working practices. The interesting thing is that the key elements of the upheaval not just reduced productivity, it was proven to do so before the changes were made. The managers knew this because they commissioned an internal report, which concluded that this would be the result. The report was ignored. Why? Primarily because the changes were textbook alterations that they (or specifically, the two most senior people) could point to as their ‘big success’ when going for their next job. Mostly, they just improved quantitative outputs which even the most senior managers agreed were not accurate measures of productivity. The senior managers just went along with it because I assume they thought it would look good on their next appraisal that they fell in line. It was all very instructive.

I look at the memos and the words in them. If they are business jargon terms common in the WSJ, Fortune, Forbes, HBR over the past 2-3 years, then it is clear that it is the latest fad, often promoted by a management consultant. This stuff is usually effectively abandoned before the new policy manuals and org charts are issued. There is generally no budget provided to actually implement the changes anyway.

If it is written in English with language pertinent to the actual business and there is a budget attached, then I pay much more attention because it might actually be relevant to the business and survive more than a year.

The STEM worker shortage? A myth if there ever was one.

Citing my source: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/03/the-myth-of-the-science-and-engineering-shortage/284359/

Oh, I knew alleged shortage of STEM workers was actually a compliant that they earned too much, and an excuse to justify bringing in cheaper overseas workers to replace them.

What was interesting was how, suddenly, all the standard arguments about how you need to pay more to attract the best talent — “if you pay peanuts, you get monkeys” and all that sort of thing — just didn’t apply. These apparently unassailable ideas were casually dismissed as non-operative for positions from middle-management on down. The double-think was quite interesting to watch. Immensely frustrating to deal with, but interesting to observe.

My anecdotal experience now that I am in my fourth decade in the work force:

1. “Modern” managers are rated based on annual performance, some semi-annually or quarterly. So they always get given “stretch” growth objectives that they usually don’t meet for sales, because they are focused on cutting costs to maintain the quarterly and annual profitability stretch goals. The basis for most stretch growth targets has as much logic as the “8 rhymes with great” new account goals for Wells Fargo.

2. One of the easiest ways to reduce costs is to squeeze the suppliers as hard as you can. The reverse auction is now standard practice through every industry that I have seen – it was unheard of before the mid-90s. So all costs are stripped to the bone – everything has to be focused on the product that will be going out the door in the next quarter.

3. Since everything is stripped to the bone, anything resembling learning or thinking about something for the future is unnecessary and does not fit into the budget. Surprisingly enough, very few people are thinking about the “stretch” goals for 2-3 years out.

4. Since the manager is not meeting their stretch goals at the end of year 1, it is time for a re-organization so all of the deck chairs get shuffled around, “lean management” is introduced and a couple of managers get axed. The staff cuts means it takes a few months for the org charts to get updated, so nobody on the floor even knows who their manager is anymore, but that is usually unimportant anyway.

5. Since the manager didn’t meet his stretch goals, he-she is gone in 2 years, and a new person fills the slot. This obviously requires another re-organization. Six months later the org charts are circulated to everybody. One-third of the positions haven’t been filled yet and several of the people have already been terminated by the time the revisions are released.

6. By this time, senior management is figuring out there is an issue with staff turnover increasing, so employee engagement surveys are commissioned. Employees never hear about the results due to the consternation that they engender in senior management. This creates a new re-organization to bring management closer to the staff to enhance communication.

7. Then the new stretch goals are announced, and the cycle restarts.

So, we see poor revenue growth, little investment for the future, good profits for a while due to aggressive cost-cutting, and disengaged employees. I think this will continue until the next stock market crash which is when a new generation of executives will have to rebuild revenue which is different from increasing profits. They will do this because profits won’t be as handsomely rewarded with high P/E ratios and they will need to show actual sales growth which means new and improved products and more engaged employees.

BTW – steps 1-7 are coming to the financial sector. Vanguard built itself from the ground-up as a low cost provider, so its in pretty good shape. The move to passive index funds with rock-bottom costs is essentially a reverse-auction process playing itself out. Similar trends are playing themselves out elsewhere in the financial sector. One day it will happen to universities and healthcare as well.

Some commentators put forward a “dominant factor” explaining the variations in the rate of productivity — energy or money. The long-term historical record provided in the chart does not support those explanations.

a) Money.

From the chart, the first long-term decline in productivity growth started around 1873 and ended around 1896. This corresponds exactly to the Long Depression — whose fundamental cause were the deleterious consequences of complete adherence to free trade by European countries, and unfettered speculation. But it also corresponds to a major monetary policy: the shift to the gold standard — in 1872-1873 by Germany and the USA, and just a few years later by European countries of the Latin Monetary Union.

All those countries were on a bimetallic standard; the demonetization of silver currency was deflationary (it destroyed money), and reinforced the depression.

In the 1930s, the figure shows fits and starts for productivity, followed by a crash after WWII — although the Bretton Woods system had been put in place. Productivity started growing again around 1948 — when the USA launched the Marshall plan, shifted to free trade, and adopted an accommodating credit policy towards Europe.

So adherence to a metallic standard? No, it looks way more complicated than that.

b) Energy.

1971 was not just the year Bretton Woods died — it was also the year when the USA ceased to be self-sufficient in oil. Despite shale oil, Alaska fields, off-shore, etc, the USA never regained self-sufficiency and productivity growth declined inexorably.

Conversely, the period 1800-1873 shows continuous increase in productivity growth, just as the Europe and the USA were putting coal and steam to use during the first Industrial Revolution.

So perhaps energy is the determinant factor?

No, it looks more complicated.

1873 coincides with the start of the second Industrial Revolution and the harnessing of a new source of energy: electricity. This did nothing to counter the decline in productivity growth. From 1896 onwards, after overcoming the Long Depression, and till after WWI, productivity growth stopped declining but stagnated — although another source of energy had just been harnessed: oil.

So no, energy is not the determinant factor either.

Productivity is the result of complex interacting factors. The chart above shows labour productivity — but the real thing is total factor productivity, which in principle takes into account items such as machinery, organisational changes and technology. There, the picture is much less clear.

I encourage people to go to the Bank of England page where the source data can be downloaded. There is also a series for total factor productivity there; contrarily to what the above chart shows (labour productivity always grew in the past, i.e. its variation was always positive), TFP went up and down, i.e. productivity diminished at times. For instance, the series shows TFP going down: -1.71%, -2.85%, -0.65%, -0.23% in 2008, 2009, 2012, 2013 respectively. Or -2.68%, -0.85% in 1974, 1975 in the aftermath of the first oil shock.

A complex, but very interesting topic.

You are assuming that those productivity measures are good.

A nation fan be very productive but producing goods and services that will make them poor in the end.

Not sure this data proves the point. It’s still an exponent – a positive one. Meaning this graph shows fluctuating rates of exponential growth. If that blue line were to stay above zero for a few thousand years, each individual would, at that point, be producing more than all of global GDP currently. (If we must use GDP, I’d prefer a per-capita measure – not too hard to calculate if time consuming). IMO, sustainability means finding the point where productivity roughly tracks population changes, and economic outputs are adequate to meet all our basic needs and some fun stuff and good food, provide ample leisure, and continue healing our badly wounded planet.

I asked an economist friend of mine at MIT how economists understood an economy function during times of significant population decline (as current demographics predict in Japan, specifically). He told me economists don’t study that because they would have to “make too many assumptions.” I don’t ask him econ questions anymore.

Galbraith the elder thought we’d all be working 15 hours a week by now and poverty would be eliminated. Still a more worthy goal than continual exponential growth on a dying planet from where I stand.

In fairness, the neolibs did promise ever higher exponential growth, just don’t think it’s a promise sane people should hold them to.

Better pay attracts more applicants, not necessarily better applicants. And since the selection process is at best a crap-shot then I really doubt that the increased cost of managers has led to much (if any) benefit.

Thank you, and I would refer anyone to James Bloodworth’s book, The Myth of Meritocracy.

I think the author is reasoning fallaciously. To begin with, he misunderstands the Nordhaus argument about the fruits of innovation. Sure, the company only gets a small part, but they still might get very rich on their small part. The public gets the bulk of the value of most innovations. That’s just how innovation works. This is one of the arguments Ed Conard makes in ‘Unintended Consequences’, but in the sense of ‘see how wonderful innovation is’.

The author would have us believe that there are few fruits of innovation, and management has caught on to this, and so they’re holding the innovations back. It reminds me of the rumors we used to hear about some item you could glue to your motor that would reduce gas consumption by half, but the oil companies have bought it and are sitting on it. I guess its good to know that nonsensical ideas never change.

As well as the exciting new technologies and medical advances the war spawned, the ‘productive’ post war period can, I’m sure, be attributed to a shared sense of relief, belief in an ever better future and a common purpose engendered out of necessity during the conflict.

New postwar governments easily and successfully capitalised on these widely held positive sentiments and set about rebuilding a better world than had gone before. The old world had failed so obviously, abjectly and completely, but this time there was a clean canvas and it was going to be different. Almost everyone in post war Western Democracies, even those jaded by less than fond memories of the prewar Depression, felt they had a stake in it this time.

Unlike today, there was also a clarity and consensus about who the new enemy was post war. There was an abiding sense that those in the West were probably on the winning team ( best measured at the time in terms of living standards), and undoubtedly on the right side of the ideological fence in the fight for freedom and democracy in the cold war certainties afforded by the apparent evils of Russian Communism.

Fast forward 30 or 40 years and that the rest, as they say, is history………..neoliberal history.

I think we need to keep the definition of productivity in mind when looking at that graph. We’ve become a financial economy. What is the productivity of shuffling money back and forth? How do you measure the productivity of that behavior? Nothing real is made and therefore what is the productive output to be measured?

I think that the problem is that neoliberalism was designed to fail.

It was little more than intellectual cover to transfer upwards the wealth of society. Basically it was cover for the rich to loot society. The author seems to think that the neoliberals have the best intentions. I am questioning that assumption.

They chose to loot a larger slice of a smaller economic pie rather than a smaller slice of a rapidly growing pie.

The neoliberal model promised that they would offer far more rapid growth than social democracy. The data is that the opposite has happened – I’m saying this is failure by design.

I agree with you but feel inclined to quibble words — Did Neoliberalism fail? Neoliberalism makes false promises but seems to have achieved great success in arriving at its intended outcomes. However, given the shape-shifting multi-headed nature of Neoliberalism I’m wary. I believe helping the rich loot society is only a small part of the intended outcome of Neoliberalism. I’m still trying to come to grips with what Neoliberalism is working toward. Several themes come up regularly — increasing inequality — increasing control from above — and others not mentioned here such as the commodification of our life and society reducing them to varieties of Market relations.

What it is working toward? Geez, should have been obvious by this time:

Inflating Financial Assets — extracting the greatest wealth from the majority!

To do so by: financialization, outsourcing (offshoring of jobs), privatization, deregulation and commodifying of labor.

The point of one world bank, one world financial exchange, one world clearinghouse, one world corporation and one world retailer should be glaringly obvious!

All the outcomes you noted are indeed outcomes of the Neoliberal project. So I agree with you — to a point. As bad as these outcomes are I’m suggesting there’s more to Neoliberalism and worse outcomes current and pending. Examine how commodifying labor is realized and beyond that.

Note the commodification of science, education, medical care … the commodification of person in terms of Facebook friends … a set of certs and experience key words on resumes … on computer representations of “human capital” in the outsourced HR department. Students have become customers for Education. We aren’t concerned citizens any more. We have become customers for government services. Our work is monitored, counted, transmogrified to sets of data that quantify us as employees and as persons. But wait — are we an employee or an agent promoting our brand of “me” into the labor marketplace? Neoliberalism is much much more odious than the mere transfer of wealth from poor to rich. We live in the age of a “Super Sad True Love Story”.

Is it still so glaringly obvious what Neoliberalism is up to?

I suspect that they did not want the far right to rise, but yes, their desire to extract wealth was very successful.

I think that the fact that the pie stopped growing as fast is an issue too – just not much left to loot. If the richest 8 people have as much as the bottom 160 million, then there’s not much left to loot from them. Unless the pie gets bigger and the bottom gets something, eventually they’ll run out of things to loot.

They wanted to loot forever and perhaps we are reaching the limits.

You win the prize for the most lucid and salient of comments, Big A!

Everything has been about inflating financial assets — everything else, war, identity politics, everything . . . is just about that one thing:

INFLATING FINANCIAL ASSETS!

Hmmm…Larry Summers keeps showing up in interviews as the righteous defender of the little people. Am I missing something here?

They who are involved in creating the problems always show up to suggest they are also the solution?

This post begins with the unfounded assumption Neoliberalism was supposed to make us richer — the phrase “was supposed to make us richer” assumes an intent. I think it’s more accurate to say Neoliberalism promised to make us richer. That promise and other pretty stories offered rationale for Neoliberal policies. After Neoliberal policies succeeded in blowing up the economy in 2008 we should be well inoculated against believing Neoliberal promises and rationales reveal the intent behind Neoliberal policies and actions.

“Neoliberal ideology … predicts that productivity growth should have accelerated. But it hasn’t.” Is productivity growth an intent behind Neoliberal ideology — or is “productivity growth” just another empty promise used to effect changes for an entirely different purpose? At this point the post argues Neoliberal policies have lead to a productivity slowdown and assumes productivity increase was the intended outcome of those policies. Employers used to “raise productivity because they couldn’t so easily rely upon suppressing wages to raise profits.” But now they can raise profits by squeezing wages and avoiding risks. Maybe that is the intended outcome. Inequality has grown “… which depresses growth …”. But perhaps increasing the level of inequality is an intended outcome.

The last assertion: “… neoliberal management … reduce[s] productivity …” continues to assume the intent for Neoliberal policy is to increase production. At this point the framework of argument splits into several lines presenting several management practices leading to reduced productivity. Neoliberal management practices:

— control employee efforts to “experiment and innovate”

— “can demotivate more junior staff, who expect to be told what to do rather than use their initiative

— pushes managers [middle managers?] toward “doing tasks that are easily monitored”

— empower management to “increase opposition to change” so that “the forces of conservatism eventually suppress technical creativity”

A common thread to all these outcomes is the increase in control from above.

Perhaps that is an intended outcome.

all money is debt ergo all profit is debt – productivity is just another word for profit, which is a euphemism for exploitation (energy, resources, labor, environment) which in turn is a euphemism for debt… so it stands to reason that as the slippery wheel of capitalism churns around in the ditch it creates an ever greater hole.

That’s assuming “all money is debt”. I have a 1-ounce gold piece in my hand and try as I might I cannot seem to think of who I owe in order to hold it, or whose “obligation” it is.

Likewise, when President Kennedy issued Executive Order 11110 to pump $4.3 billion of debt-free money into the economy (since it was based upon silver and not issued by decree of the Federal Reserve, and no interest would have to be paid back to them).

I have some of those. They look like money, they are denominated in money, but they ain’t money.

Money is a record of how much wealth you are owed. Gold pieces are wealth.

If you think otherwise allow me to give you $11 for your gold eagle. That’s a nice 10% premium for you.

Not buying it, gold has been money for thousands of years. Of course you can record “how much wealth I am owed”. In gold. And don’t confuse the face value of a gold coin with its weight, of course you would find no sellers for your $10 face value gold eagle at $11 because it is worth much more than that:

http://www.ebay.com/itm/1926-10-Gold-Eagle-Indian-PCGS-MS63-/122374474314?hash=item1c7e164a4a%3Ag%3A4LYAAOSwx6pYsiRR

When it was issued in 1926 the coin could be exchanged for $10 worth of debt money. And that should tell you everything you need to know about debt money.

I had a feeling you wouldn’t be convinced, but I’m going to try again.

Wealth is man-made goods and services, eg. gold artifacts.

Debt is wealth owed.

Money is a record or token of debt, an IOU.

Different levels of abstraction. The map is not the territory.

Sure, you can buy stuff with gold, that is called barter.

Sure, you can make a debt token out of gold, but as soon as the value of its gold content exceeds its face value it is no longer money, it is wealth.

The fact that gold is a better store of value than money supports my case, I think.

Well, I suppose strictly speaking, the gold debt token is still money even when its monetary value is less than its wealth value. But it would be tricky to redeem its monetary value without losing its wealth value.

Basis for a book. Some other possible culprits besides those mentioned by the author:

Much of the nation’s manufacturing base was exported to other nations.

Money has been channeled into nonproductive assets and services, including real estate, passive financial assets, military and surveillance assets, etc.

Anti-trust laws have been neutered and enforcement is nonexistent. This has led to the rise of monopolies and oligopolies that have erected effective legal, capital and market structural barriers to prevent emergence of more productive competitors.

Domestic demand has been intentionally suppressed through policies that have encouraged wage suppression and stagnant real incomes, rising levels of household debt, and led to extreme concentration of wealth which is largely invested in nonproductive passive assets.

Privatization of what were formerly publicly owned assets and services has done little to increase productivity and in fact has been largely counterproductive.

Compensation policies for CEOs encourage use of corporate cash for nonproductive purposes such as corporate stock buybacks.

Much private sector debt has been used for nonproductive leveraged buyout acquisitions.

I am sure there are many other factors, including public health issues and healthcare costs. The neoliberal ACA solution appears to be a flawed solution.

Again, everything you stated can be reduced to one single phrase:

inflating financial assets

Explained in detail by much superior minds than my own!

It’s inequality stupid read my lips. It’s unhealthy . People don’t have to openly rebel against something to show they are unhappy . The whole idea of something in common, we are all in this together has been destroyed in the workplace and elsewhere by neoliberalism and the massive bureaucracy that goes with it ( yes you read that right ) because it all comes down to control without any useful product at the end and in the process the natural ( yes you read that right ) of human beings to co-operate, collaborate and trust one another is destroyed and the degradation in the human spirit, the infantilisation of the people etc etc ….and is it any wonder that productivity declines . No it isn’t .

Why does “productivity” always refer to LABOR productivity, not CAPITAL productivity?

Overall, they’re roughly inverse functions.

To clarify: capital is always judged on “return,” which is essentially its price. That is not at all the same as how much is produced per unit of investment, at least unless you accept the strongest market fundamentalism. “Return” is the equivalent of wages and salaries.

And a digression(?): one of the big flaws in economics is that it conflates human made capital with natural capital. That’s a further reason returns to capital are, umm, uncommunicative.

It was never supposed to make us ALL richer, silly.

To put it all simpler: like hell the private guys need public companies all wrecked out. They take public companies in GOOD shape, still more if EXCELLENT – high productivity, efficiency, no debts – and wreck them out. They simply pocket company’s assets and throw it out to rot. “Privatisation as key to efficiency” is simply neoliberal b***s**t designed to deceive the naive.

“Neoliberalism Was Supposed to Make Us Richer”

The goal of any snake oil salesman is to make “Us”, the snake oil salesmen’s richer, not all of Us.

So, the snake oil didn’t cure cancer, big surprise.

The snake oil salesman is eternal, will humans ever learn?

If it looks like a conman, if it talks like a conman, … it is a conman.

Neoliberalism is the ultimate “Nigerian letter”

The big question then is why didn’t the Nigerian letter make you rich?