By Marcos Reis, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Economics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and Igor Rocha Researcher, Cambridge Society for Social and Economic Development. Originally publised at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

Brazil’s current economic scenario does not resemble the emerging economy that until recently fueled the optimism of analysts and investors.

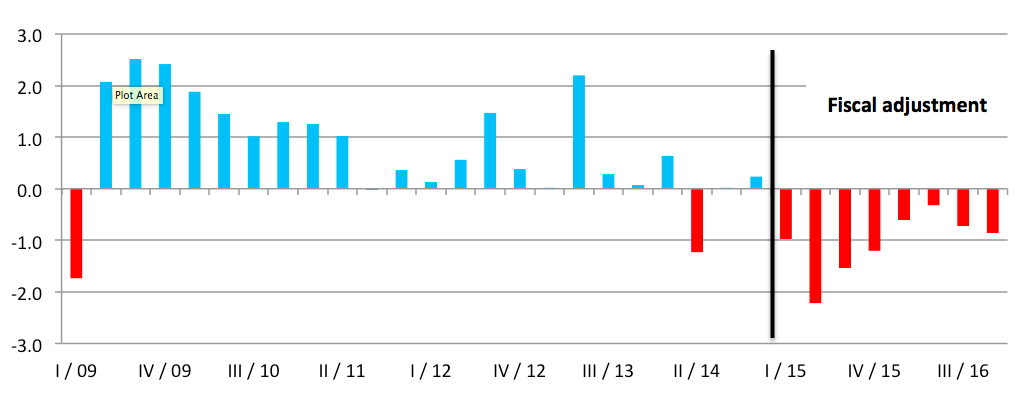

In 2015 and 2016, the country’s economy shrank by, respectively, 3.8% and 3.6% — mainly as a result of the collapse of investment levels, falling commodity prices and consumption, and government policies of fiscal austerity. Why has Brazil, once hailed as one of the most successful among emerging countries in terms of economic growth with social inclusion, adopted the path of austerity? What were the antecedents and consequences of this decision? The graph below shows that, in relation to economic growth, the result does not seem to be desirable.

Graph 1 – Quarterly GDP Growth Rate

Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE)

After the re-election of President Dilma Rousseff in October 2014, the government began to implement austerity policies. There are two main reasons for this turn: First, and most important, was the pressure exerted by the financial market, which insisted that a severe fiscal adjustment was necessary to maintain the degree of investment endorsed by the major international rating agencies. Second, was the belief promulgated by her government’s economic team that a severe fiscal adjustment could be implemented without negative consequences in terms of GDP and employment.

Rousseff began the half-turn of the economic policy when Joaquim Levy was appointed as the Finance Minister. In one of his first speeches as Minister, in February 2015, Levy said, “When we get our house in order, the private sector will find new opportunities, new markets, and Brazil will return to a path of growth.” In other words, he believed that austerity would bring the internationally renowned “confidence fairy” to Brazil. Nevertheless, as stated by Joseph Stiglitz “the confidence fairy that the austerity advocates claim will appear never does, partly perhaps because the downturns mean that the deficit reductions are always smaller than was hoped”.

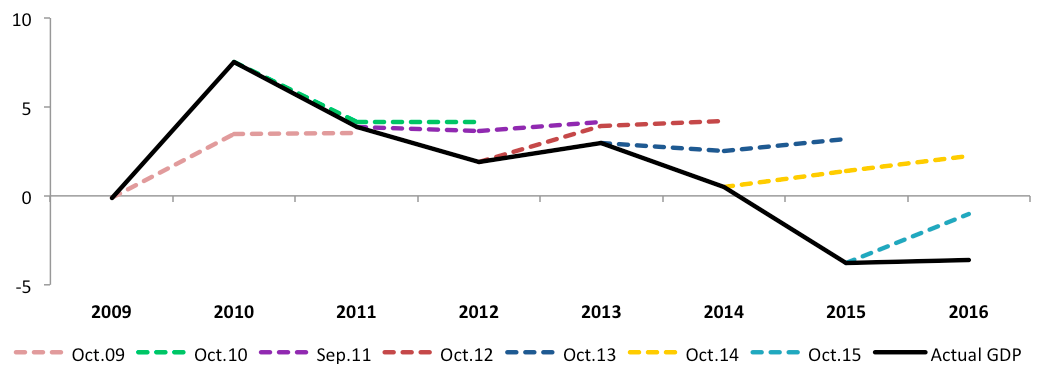

In practice, other experiences such as that of the Euro Zone had already served warning of the fallacy of the growth promise of the austerity prescription. Not surprisingly, Rousseff’s attempt to promote a fiscal adjustment has actually contributed to the deterioration of the government’s fiscal position, and of the country’s levels of economic activity. Cutting government spending generated a negative result in terms of revenues. Fiscal contraction at a time when the state should act in a countercyclical way seems only to accentuate the strong recession and undermine the economic recovery. The mismatch between expectations and outcome is latent. The graph below shows the real GDP in recent years and (in broken lines) the forecasts made by the International Monetary Fund, which were typically overly optimistic.

Graph 2 – Real GDP growth and IMF Forecasts

Source: IMF

It was argued that a fiscal contraction would ultimately result in economic expansion, since it would trigger positive expectations in the private sector, thus allowing a return to the much-desired scenario of low inflation and high growth. However, such discourse lacks robust theoretical foundation and empirical proof. For example, in a recent article, three senior IMF economists note that “austerity policies not only generate substantial welfare costs due to supply-side channels, but also hamper demand — worsening employment.” In this way, Paul Krugman remembers, “in late 2012, the IMF’s chief economist, Olivier Blanchard, went so far as to issue what amounted to a mea culpa: although his organisation never bought into the notion that austerity would actually boost economic growth, the IMF now believes that it massively understated the damage that spending cuts inflict on a weak economy”.

In addition to contributing to the biggest recession in Brazilian history, the fiscal adjustment period has also led to deterioration of other indicators. The gross debt of the federal government as a proportion of GDP, which stood at 57% in November 2014, is growing steadily after the start of the adjustment program, reaching 69,7% of GDP in January 2017. The result can be explained both by debt increase, due to the deficits aggravated by the low revenue, as well as by the decrease of the denominator of the fraction (GDP). This situation is problematized in an environment where the nominal interest rate is at 12.25% and the real interest rate is around 7%. Furthermore, the 12.9 million unemployed people registered in January 2017 was a record in the country’s history, at 12.6%. It is estimated that the number of unemployed people should reach 13.7 million by the end of the first half of 2017.

Even with such results, the fiscal adjustment continues to be presented by the government as a sine qua non condition to restore the investors’ confidence in the economy, and therefore of economic recovery. Moreover, the government continues to pursue an agenda exclusively focused on supply side measures. Currently, economic policy has three priorities: i) creation of a spending ceiling for the next 20 years ii) reform of social security and iii) increase labour market flexibility.

As the results show, boosting the “confidence” of investors and entrepreneurs it is not enough to achieve an economic recovery. Therefore, an agenda to restore the economic dynamism cannot be based in a fiscal adjustment, but requires measures that have positive impacts from the short to the long term. Some examples are: (i) the maintenance of income transfer policies and jobs creation; (ii) the expansion of public investment programs, particularly in infrastructure, (iii) end of tax exemptions without counterparts, (iv) a broad tax reform to increase the progressivity of taxes and reduce their complexity, (v) seek real interest rate convergence to those practiced in other emerging economies and (vi) policies for regulation of the exchange rate market to control the high volatility of the domestic currency.

Not sure if its just me, but an Ameritrade ad seems to want to take over the page. I have to force stop the load to keep it from hijacking the page load.

Could be. They didn’t serve me that one. I did notice that the ZeroHedge page is so loaded up with crap that I couldn’t scroll down to read the article (Kunstler interview.)

Ameritrade took over the page on Firefox, so I switched to the Chrome browser, where Ameritrade did not take over.

Why do so many, like this author, still attempt to rebut neoliberalism on its merits, or lack thereof, when it has long been obvious that no even slightly rational person believes that austerity, or structural adjustments, or whatever they’re calling it this week, will really expand the economy.

This whole article, including its obligatory references to Stiglitz, could have been copy/pasted from 1996.

It’s time to move on. And it’s time to call the Chicago/Austrian/Whatever school for what they are: crackpots.

Yes, Alan Greenspan is a crackpot. And if his bullshit weren’t so profitable to the banks, he would be widely regarded as such.

The New Liberals are up their with global warming deniers.

Another problem is that every country is hawking itself around and touting as being the most business-friendly, having the bendyist of flexible labour markets and dolling out the lardiest of corporate welfare. Where, then, are the differentiators for a country like Brazil?

Other countries are “winning” the race to the bottom, so even Brazilian efforts to crush labour and dismantle the social safety nets are too little, too late

Re: The winner to the bottom

What does the winner do with their prize?

Your people get to have terrible jobs while everybody else is unemployed.

You get an attaboy from Mr Haygood.

The elites make tons of cash. Example A: Mexico, which post-NAFTA produced a large number of Mexican billionaires, even as Mexican wages are now lower than China’s…

And no mention of the coup to ensure that Brazil made even more draconian cuts and to pass a constitutional amendment ensuring that they wouldn’t increase their national debt any further?

Is this article a year old? or just a hit piece against the Workers Party (PT)? Or April Fools?

You make an excellent point about the article omitting to mention the constitutional coup, but I can’t see by any means how Reis can be accused of writing a “hit piece” on the PT. His only criticism of PT is that Rousseff applied austerity– something that she most certainly did and then whipped for it in Congress, and which most likely led to her downfall, by decapitating her base.

Placing blame where blame is rightly due does not constitute a hit piece; c.f. how the Democrat Party has reacted to election post-mortems.

I think this shows the deep problem of how intellectually captured so many, even on the left are, by neoclassical economics. I don’t think anyone can question Rousseffs past history as a fighter for ordinary people, but I’ve no doubt she and her advisers honestly thought that a bout of austerity could work economically. Most of us (I’m no exception) are programmed to think that its ‘obvious’ that sometimes you have to cut back on debts and that in the long run it is more prudent not to spend too much. It shows the great importance of blogs like NC pushing so hard for intellectually coherent alternatives.

By all means, point the blame cannon where it is due…. This would have been a very valid article a year ago, but if it just goes and ignores everything that has happened in the last 6 (?) months it leads the less well informed reader with the impression that that the Workers Party is the only side pushing bad policy. Which means it’s a hit piece.

I’m at the point where i roll my eyes when i see things like ‘confidence fairy’ arguments. I know the neoliberal ideology is still strong, in parts, but does anyone believe this anymore?

In my view, dilma thought she could blow off her base and cut a deal to accommodate the oligarchs on her right. I don’t fully understand why she did it. She seems more humble than the clintons or obamas. She didn’t make tons of money.

See PlutoniumKun’s point above, which I think is right on target. Too many leftist leaders– included Rouseff who was tortured by the junta– are 100% spot on when it comes to social issues but are well-intentioned and brutally misinformed when it comes to the economy. Even though it is the economy that most affects those they want to help. I do not personally think Rouseff would sell out to austerity for political expediency; she is too moral. But the idea that her economic knowledge, like that of too many on the left, is sorely lacking, is very persuasive.

No nobody believes this shit anymore. As reflected in Krugmans comment about the IMF. They didn’t believe austerity would bring growth, they just didn’t think it would cause that big of a contraction.

Her downfall was not principally led by her being whipped in congress, but rather because of the all too predictable outcome of austerity measures, a swift economic downturn. Mix that with billion R$ wasteful football stadiums and corruption, and an extremely hostile mainstream media, installing an irrational middle-class fear that PT was on the path of a left-wing dictatorship and that Brazil would become like Cuba or Venezuela. It was also Rousseff’s political isolation. Unlike Lula, she didn’t always fully understand the political tides, had few people she trusted, and wasn’t very apt in navigating a treacherous congress.

But it was definitely austerity under Rousseff that would lead to her downfall, as the economic downturn was the catalyzer for everything else to follow.

GDP = Government Spending + Non-goverenement Spending + Net Exports. So how could reductions in Government Spending ever grow GDP?

What next? Cure anemia by applying leeches?

+change in aggregate debt.

FIFY

Rodger,

Economys are like a balloon, you press at the public sector end and the private one inflates.The tricky part is drawing the line between them

I would have liked more background on the ‘First, and most important, was the pressure exerted by the financial market, which insisted that a severe fiscal adjustment was necessary to maintain the degree of investment endorsed by the major international rating agencies’ part.

Was the market right? Was this pressure real?

What happened to investor returns? That is, we’re interest and principal payments made?

And WHO are the actual individual people described as “financial markets” applying pressure, and what is their relationship to the coup leaders now running Brazil?

In a way, this is a return to the Citibank-led debt expropriation of Latin American economies in the 1980’s. With Temer standing in for the Generals of the time. Unpayable debts. Austerity. It finally led to a debt write down, unthinkable today.

Was it under Walter Wriston, John Reed or Robert Rubin who engineered this? Probably John Reed, with little Robert at his elbow.

Someone I knew and won’t mention, was editing bank internal documents at that time, and was appalled at the degree of direct involvement in anti-democratic and coup activity engaged in by the bank, especially in Central America, They had active intelligence operations on commander Tomas Borges and basically everybody on the continent.

In general, the leadership of the PT (Workers Party) was always a firm believer in budgetary control and sound finance (as opposed to functional finance).

No wonder they caved in to pressure from the markets. Some even go as far as proposing that the central bank sell its dollar reserves in order to “pay for” public works spending to stimulate the economy. They do not understand that a currency issuer like Brazil doesn’t need to sell dollars in order to get Reais, its own currency.

With the 370 billion dollars held by the central bank Brazil had more than enough “ammunition” to defend the Real exchange rate while maintaining the needed level of public spending to keep the economy growing. The dollar reserves are higher than the total amount of dollar debts incurred by the government plus state-owned companies such as Petrobrás.

Brazil is a net creditor in dollars – but it behaved as a net debtor, terrified by the prospect of pressure from the international financial markets.

The current recession is the deepest economic downturn in the country’s history – but it likely could have been avoided “if only” the Dilma administration had an understanding of how modern money works. Sadly, they didn’t.

Is there any example of a country that has disregarded the austerity program and had success? By not putting the taxpayers in hock to pay for banker failures like Ireland did, Iceland has come out better. It was still painful for many private borrowers who had to pay for loans made in Euros that doubled over night. Don’t know what the government policy is concerning austerity? Latvia is the best example of the failure of austerity along with Greece. Has any country used policies that Naked Capitalism would recomend?