By Alicia Garcia-Herreror, a Senior Fellow at Bruegel and a non-resident research fellow at Real Instituto El Cano. She is also the Chief Economist for the Asia Pacific at NATIXIS. Alicia Garcia Herrero is currently adjunct professor at City University of Hong Kong and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) and visiting faculty at China-Europe International Business School (CEIBS). Originally published at Bruegel.

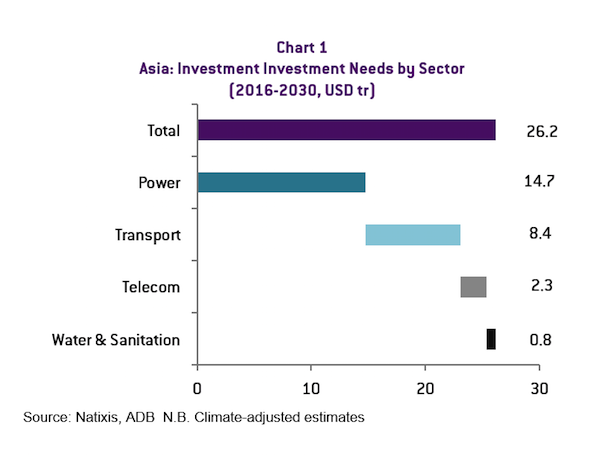

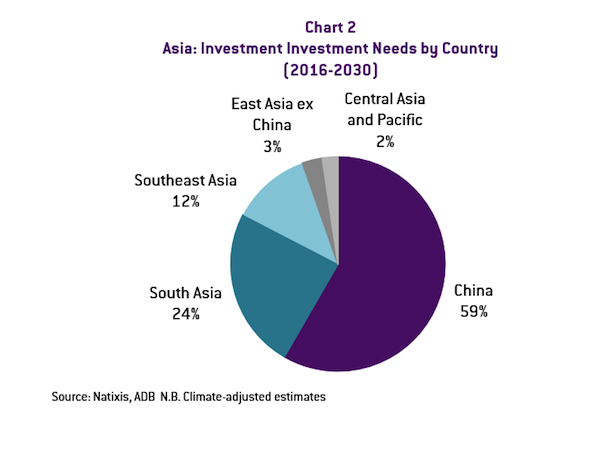

There is no doubt that Asia needs infrastructure. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) recently increased its already very high estimates of the amount of infrastructure needed in the region to 26 USD trillion in the next 15 years, or 1.7 USD trillion per annum (Chart 1). The great thing about the China driven Belt and Road initiative is that it aims to address that pressing need, especially in transport and energy infrastructure. But this is easier said than done. The a-priori is that the financing will be there thanks to China’s massive financial resources.

Chinese authorities have come up with their own estimates of the projects that will be financed. The numbers start at USD 1 trillion and go all the way to USD 5 trillion in only 5 years. In the same vein, the official list of countries does nothing but increase over time to more than 65 countries today.

But There Is a Limit to How Much China Can Finance

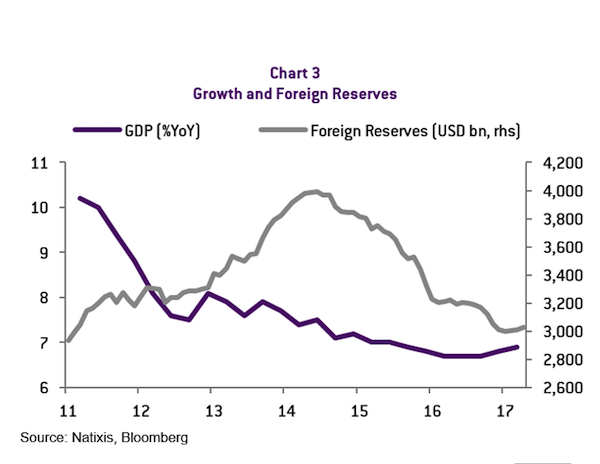

Such a-priori was probably well taken when China was flooded with capital inflows and reserves had nearly reached USD 4 trillion and needed to be diversified. In the same vein, Chinese banks were then improving their asset quality if, anything, because the economy was booming and bank credit was growing at double digits.

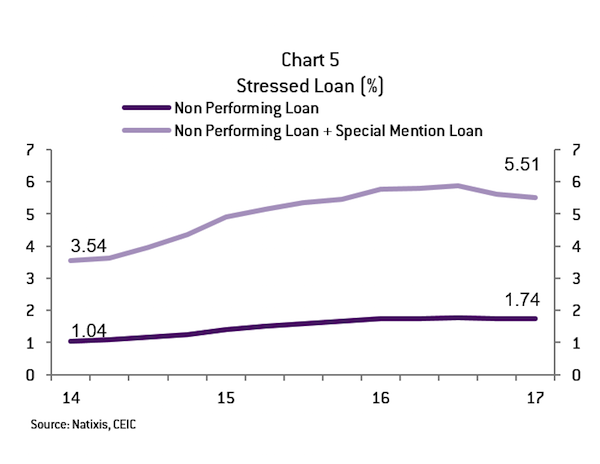

The situation today is very different. China’s economy has slowed down and banks’ balance sheets are saddled with doubtful loans, which keep on being refinanced and do not leave much room for the massive lending needed to finance the Belt and Road initiative.

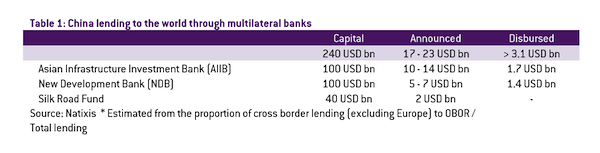

This is particularly important as Chinese banks have been the largest lenders so far (China Development Bank in particular with estimated figures hovering around USD 100 billion while Bank of China has already announced its commitment to lend USD 20 billion). Multilateral organizations geared towards this objective certainly do not have such a financial muscle. Even the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), born for this purpose, has so far only invested USD 1.7 billion on Belt and Road projects.

As if this were not enough, China has lost nearly USD 1 trillion in foreign reserves due massive capital outflows. Although USD 3 trillion of reserves could still look ample, the Chinese authorities seem to have set that level as a floor under which reserves should not fall so that confidence is restored (Chart 3). This obviously reduces the leeway for Belt and Road projects to be financed by China, at least in hard currency. Against this background, we review different financing option for Xi’s Grand Plan and their implications.

How to Finance the Belt and Road?

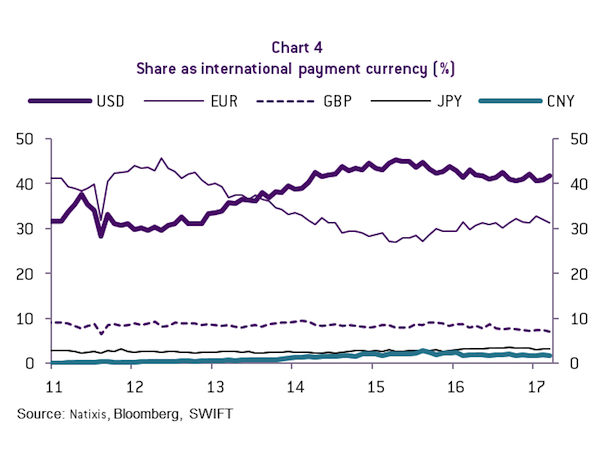

The first, and least likely, is for China to continue such huge projects unilaterally. This is particularly difficult if hard-currency financing is needed, for the reasons mentioned above. China could still opt for lending in RMB, at least partially, with the side-benefit of pushing RMB internationalization. However, even this is becoming more difficult.

First, the use of the RMB as an international currency has been decreasing as a consequence of the stock market correction and currency devaluation in 2015 but still some of the Belt and Road projects could be financed in RMB in as far as the borrowing of a certain host country would be fully devoted to pay Chinese construction or energy companies (Chart 4). This quasi-barter system can solve the hard-currency constraint but poses its own risks to the overly stretched balance sheets of Chinese banks. In fact, their doubtful loans have done nothing but increase during the last few years, which is eating up the banks’ room to lend further (Chart 5).

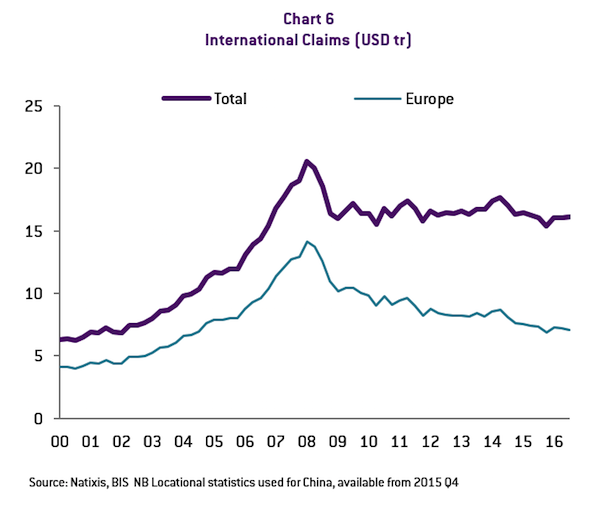

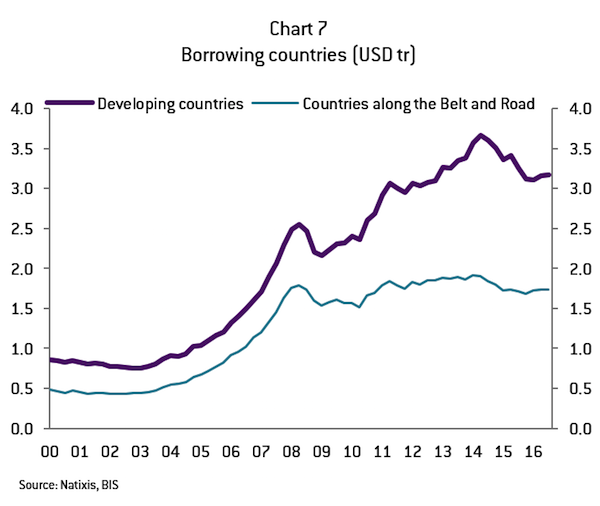

A second option is for China to intermediate overseas financial resources for the Belt and Road projects. The most obvious way to do this, given the limited development of bond markets in Belt and Road countries as well as the still limited size of China’s own offshore bond market is to borrow from international banks. Cross border bank lending has been a huge pool of financial resources, especially in the run up to the global financial crisis. Since then they have moderated but the stock of cross border lending still hovers above 15 USD, out of which, nearly half is lent by European banks. Out of the USD 15 trillion, about 20% is already being directed to Belt and Road economies, with European banks being again the largest players (Chart 7).

Still, in order to finance the USD 5 trillion targeted in Xi’s grand plan for the next five years, you would need to see growth rates of around 50% in cross-border lending. While such a surge in cross-border lending is not unheard of (in fact, it happened in the years prior to the global financial crises), the real bottleneck would be the rapid increase in China’s external debt, which would go from the currently very comfortable level (12% of GDP) all the way to more than 50% if China were taken on the debt, or something in between if co-financed by Belt and Road countries.

A mix of option 1 and 2 lies on the use of multilateral development banks to finance the Belt and Road projects. In fact, China is a major shareholder of its newly created multilateral banks (AIIB and New Development Bank) but less so in existing ones (such as ADB, EBRD or the World Bank). This means that the financing burden can be shared (to a lesser or larger extent) with other creditors, while still keeping a tight grip on the construction of such infrastructure (at least in China-led new organizations). While apparently ideal, the problem with this option is that the available capital in these institutions is minimal compared to the financing needs previously discussed (Table 1).

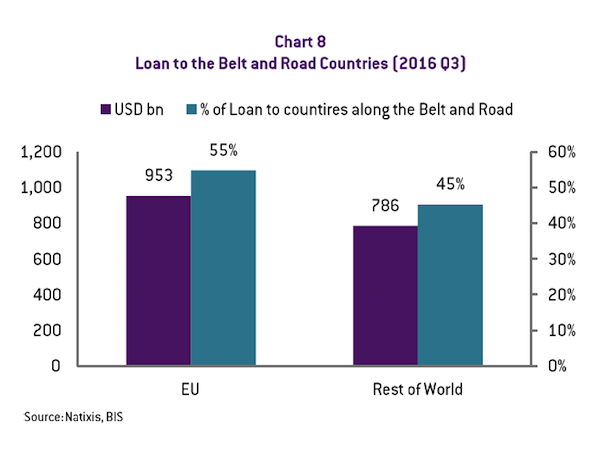

It seems that China cannot really on its banks alone – no matter how massive – to finance such a gigantic plan. The key source of co-finance would logically be Europe at least as long as bank lending dominates, which will be the case for quite some time in the countries under the Belt and Road. In fact, European banks are already the largest providers of cross border loans to these countries so it is only a question of accelerating that trend. Furthermore, the geographical vicinity between Europe and some of the Belt and Road countries could make the projects more appealing (Chart 8). In addition, the European Union has its own grand plan for the financing of infrastructure – among other sectors – namely the Juncker Plan, which could serve as a basis to identify joint projects of interest to both EU and China. In this vein, EU-China connectivity platform was launched by the European Commission in late 2015 exactly to identify projects of common interest for the Belt and Road and the EU connectivity initiatives, such as the Trans-European Transport network. All of this bodes well for Europe to become an active actor in China’s Belt and Road initiative, not only to provide the financing but also to identify projects of common interest.

It goes without saying that other lenders, beyond Europeans, are welcome to finance Belt and Road projects as the ensuing reduction in transportation costs and improved connectivity should be good for the world as a whole. However, Europe’s particular advantage in this project should make it a leader on the financing front bringing the old continent closer to China.

All in all, the Belt and Road is great for supporting high demand in Asian infrastructure, but there is a limit on how much China can finance. The slowdown of the economy and the limits on the use of foreign reserves are some of the impediments. Furthermore, Chinese banks balance sheets, the largest source of financing so far, are increasingly saddled by doubtful loans, which limit their lending capacity. As for official multilateral development agencies, their funding sources remain limited for the extent of the project. Against this background, European banks-the largest cross-border lenders in the world – are well placed to step their already large financing to Belt and Rod countries. Furthermore, Europe’s proximity with some of these countries can make some of these projects more appealing for Europe as well. Thus, we should expect private and public European co-financing of Belt and Road projects to increase over the next few years and, with it, European interest for Xi Jinping’s Grand Plan. This should bring Europe closer to China.

What is this ‘hard currency’ of which you speak? García-Herrero bases her entire analysis on fictitious monetary limitations, not on real resource limitations. For her, apparently hard currency means only USD or RMB backed by… Vishnu knows what.

In the case of infrastructure built abroad, the main costs would be materials and labour. In the case of materials (I assume mostly concrete and steel), China has so much surplus that it is accused worldwide of dumping and has been building ‘ghost cities’ at home. There is no reason why the PROC government cannot obtain these under-priced materials locally in RMB. Then there is labour, which at least on the Chinese infrastructure projects I’ve seen, tends to be mostly Middle Kingdomers imported in for the job, also paid in RMB.

So why would any of these expenses necessarily entail a decrease in reserves, or recurring to local, or even worse, foreign banks for credit? (at this point, I note García-Herrero’s time with the IMF and it all makes sense). Of course, using Chinese materials and labour for projects significantly decreases the multiplier advantage to the host country’s economy, but that is another hill of beans, one which García-Herrero makes no attempt to climb here.

I’m no China bull, and the article is 100% right to point to the imminent problems in the Chinese credit system, but having enough resources to build projects is not an immediate concern for the CCP.

Thank you, RG.

I have also observed in Africa, including the various archipelago off the east coast, where China has built / is building infrastructure. It’s not just the raw materials and labour, food and lodgings (sometimes shipping containers with air conditioning units attached) are also shipped in. I am told by a friend from DRC that prostitutes have tagged along there, so local suppliers have been priced out.

When in Mauritius at the turn of the year, Chinese workers were working even on public holidays and week-ends.

So Jane Jacobs’ warning about Transplant Zones (Cities and the Wealth of Nations) would be important. That is, “development” by installing artifacts that don’t connect with the local economy, and won’t induce any local changes.

I haven’t read the Jacobs work you mentioned, but I think there are two issues here, namely the two multiplier benefits of infrastructure.

The first comes from the money paid to those working on the projects and those supplying the materials. This money boosts aggregate demand wherever it is paid. In this case, however, there is limited connection to the local economy because most of the workers’ earnings would ostensibly be brought back to China and spent there.

The second multiplier is the effect of improved infrastructure on the local economy. This may help locally if it makes the local economy more efficient. (e.g., a local factory is more efficient it it can bring in supplies and workers over paved roads or rail.) But conversely, if the infrastructure is too expensive and/or advanced for the bulk of the population to use due to a technology gap or privatisation, this latter multiplier will be diminished.

That’s pretty much her point. The book is focused on development of cities (her quantum of development) but the basic ideas seem right at other scales, too. Most cash-crop development in Africa seems to have impeded development. Ditto petro-economies. They remain things in themselves, and don’t hook up with most of the society.

At least one of the implied, if not openly stated, motivations for the plan is to absorb excess construction capacity within China. This strongly implies that they intend to do exactly what you are suggesting, even if it would be cheaper to use local labour and materials (it would no doubt be very expensive to transport huge quantities of concrete and steel across central Asia). The possibility of this stirring up local resentments is very strong – although I suspect the Chinese are well aware of this as they are usually very sensitive at how they are percieved in other countries. I think they will know they would have to proceed with caution so as not to create a backlash.

The other related issue with the article is the assumption that European banks would be happy to lend to projects like this. Chinese construction projects are invariably political – they are not intended to produce conventional economic returns, so its hard to see how you could satisfy normal lending criteria against the Chinese determination to build links to achieve geopolitical ends. Not that I’m suggesting of course that European banks are in any way competent, but even the worst run ones would certainly hesitate when faced with the problem of trying to get repayments from the operator of an Tajikistani/Chinese railway.

The other issue of course is corruption. Even within China, vast sums of infrastructure money has gone into myriad pockets. Its hard not to conclude that some of the proposed projects – the Nicaraguan canal to compete with the Panama canal comes to mind – are nothing more than giant bezzles. How the Chinese will deal with this is anyones guess since they haven’t succeeded on their home territory. Bringing Chinese construction oligarchs together with Central Asian dictators has the potential to create projects that will make Uber look like a model of ethical behaviour.

I assumed given the author’s CV (BBVA, Santander, IMF…) that the European banks’ willingness to lend would be one area where she would have a fairly good understanding. Whether the CCP would be naive enough to hop into bed with that particular devil is another story.

As to corruption, personally I see that more as a matter of capital controls (which in China are clearly as watertight as Huangguoshu) than as a matter of restricting infrastructure spending to prevent it. From a macro perspective, it makes little difference if overprices are paid so long as they get sent back to circulate in the Chinese economy.

Lastly, we saw those “local resentments” first hand here a few years back when the Chinese came to build dams in Santa Cruz. But whether it was local pressure, or Chinese sensitivity, the contracts were written to specify the percentage of local labour and materials that had to be used.

PK, do not forget how banks operate internationally: they don’t care about the profitability of their investments as long as they have official warranties on their returns.

this bbc film from 2011 shows precisely what everyone mentioned above…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kSbZ1wxV87c

The only infrastructure projects China should consider are clean water, clean air, safe baby formula, etc.

That is, to make living in China safer, not to export more stuff to accumulate more dollars, (if they can ascend to status of the next exclusive issuer of global reserve fiat currency not restrained by gold nor silver, to conquer the world by making it dependent on China).

One wonders whether the US will allow the EU to play a (full) part in these projects (regardless of the limitations cited above). EU cooperation with China gives the EU some options / independence (although, having worked in / with Brussels from 2007 – 16, one can often rely on the EU to sell itself cheaply to Uncle Sam. Gaullist, the EU is not). The US, as per a recent interview by Larry Wilkerson, can always wreck matters with its jihadists.

Yeah, this article covers the financial risks, but they sure neglect the geopolitical ones. Some of the poorest countries in Europe and Asia lie along these routes. Unless they plan on guarding the entire span, robbery and sabotage are going to be a fact of life.

Robbery yes. Sabotage why? My experience is theft of materials, inducing installed plant, is more possible than sabotage.

Such as overhead phone wire taken to make trinkets. Attitude of local was “stupid white man leaving valuable metal up in the air.”

Robbery is a way of the world.

I guess they’re poor because they are landlocked. The last two centuries have favored coastal countries. There is every reason to suppose these countries will rapidly develop their economies once the railway becomes fast and reliable.

We should recall the way USA grew along the railways if we are in any doubt about it.

Paying for the infrastructure? Pay in RMB. Redeemable in Chinese products, and think of the costs as “seed money” for those finished goods, with the interest on the investment being repaid by taxes on those manufactured goods, or tolls on the infrastructure.

I suggest the Author of this article, Alicia Garcia-Herrero, read and think about, that financing option.

China make what most workers along the new silk road want to buy.

The biggest single impediment is some countru stiring up Muslim unrest, such as Pig Fat is used to Grease the machinery. I do wonder which country would have an interest is striing up such unrest.

>China make what most workers along the new silk road want to buy.

It is that simple, you need a PhD in Finance to be able to not understand it.

I think the author is just angling for the EU to get a slice of financing for this Chinese development.

Absolutely agree. The EU damned this Belt and Road in the recent international meeting in Beijing and the only reason it might have is financial – it expects a bigger share.

So the first two questions are:

1) What are the One Belt One Road projects?

2) What resources are required?

3) Who has those resources? No-one expects the Spanish Inquisition.

We can sort those, then think about finance — unless we’re the kind of people who only think about finance.

Here is some other thoughts on the Silk Road and very different from the author.

http://www.atimes.com/article/xis-wild-geese-chase-silk-road-gold/

Pepe Escobar

It will be the Chinese Century.

Last month I read Brooks Adams marvellous 1902 book, The New Empire, which is a survey of historical forces in the growth and decline of empires from the first days of civilization. The work, in many ways along lines Toynbee was to follow, concludes with the Japanese Russian War over China about to commence and sets out the blueprint for the 20th century US empire.

Adams’ thesis is that the primary dynamic for empire and the accordant accumulation of wealth is controlling the flow of east-west trade. In contrast to much of the advanced and emergent world destroying its wealth on military expenditure (about as productive an “investment” as residential housing) I cannot but wonder whether Xi’s ultimate goal with this trade strategy is empire. If it were, he’s following exactly the very well worn proven path.

Very interesting indeed. Western world has been pauperized and can no longer afford Chinese goods or technology while pay parity with the west has been achieved.

First option of Chinese elite: raise standard of living for all Chinese, massively reduce inequality, increase social security, health care and welfare, allow for more children, lower retirement age reduce workaday/work week to boost income and internal demand for Chinese goods produced while exports collapse.

Ain’t gonna happen because of one good reason. When people are richer and more secure they demand more political rights and power i.e. they would want to expel this autocratic clique who run China.

Second option of Chinese elite: Capital export and financialization of economy while keeping Chinese people’s income in check, forcing them to work hard to survive uncertain of future so clique keeps power while getting richer via return on capital investments in foreign countries.

This is the only choice for any clique who want to get richer and stay in power, bifurcate economy into thriving financial capital system and dying mainstream economy.

This is the end game for any Supply Side Economic fanatics of greed, a path China chose and follows the US into global neo-feudalism.

OBOR is nothing but massive reorientation into Chinese capital exports away from goods’ exports. In ten years like in US, China biggest product will be Chinese treasury bonds while production made by robots or Hindu.

You’d think the world’s preeminent authority on Communism would be able to make #1 work here, but I don’t think it’s “on” as it were, although for slightly different reasons. I would argue that there is already an autocratic clique, and that the desire to keep that clique in place is the real hindrance. China wants the same vacuous Capitalist successes of the west, and you’re right: they’ll get there by doing the same things – entrenching massive inequality, wage depression and political heavy-handedness in the name of profit.

Sad!

I doubt lack of funding will be a major impediment to development of China’s New Silk Roads projects in a world awash with liquidity. Although China might lack the foreign currency reserves to directly fund “Belt & Road” infrastructure development entirely out of pocket, there are alternative sources of capital besides China’s foreign currency reserves and Western-controlled supranational organizations. Transnational banks and corporations could play prominent roles through a combination of bond issuances, project financing and vendor financing, respectively. The PBOC could guarantee debt servicing cash flow shortfalls from its foreign currency reserves and China’s ongoing current account surpluses. Other regional sovereign beneficiaries might also choose of support specific aspects through both debt payments from project cash flows and sovereign guarantees. While creditors and investors need to be mindful of the potential for theft and corruption, as other readers noted above, they wouldn’t be without leverage IMO.

People should call it the Greater World China Co Prosperity Sphere to understand what China is really working to create.