Yves here. A big shortcoming of this analysis is that it assumes that loans are funded by deposits, which is not correct. However, China also has a substantial shadow banking system. Those of you who remember the crisis know that it was the result of the freezing of the repo market, which funded about half the balance sheets of investment banks, and other systemically important players, like AIG and JP Morgan, were exposed in a big way to the collapse in prices of assets that were security for repo.

But having said that, some of the discussion in this article, particularly regarding interbank lending, oddly suggests that banks themselves don’t trust the central bank backstop or have operational issues. Any input by informed readers would be very much appreciated.

By David Llewellyn-Smith, founding publisher and former editor-in-chief of The Diplomat magazine, now the Asia Pacific’s leading geo-politics website. Originally published at MacroBusiness

From Vimal Gor at BT:

April was a divergent month across economies and asset classes. Whilst the US economic picture continues to deteriorate, we believe a Fed hike in June is locked in, absent an exogenous shock. This is driven primarily by the continued strength in the employment picture. In contrast the economic data from Asia, and China in particular, is notably upbeat, a dynamic we think is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. European data was somewhere in the middle, not too strong or too weak, but pretty good for an economy which was facing a depression not so long ago.

Asset classes also showed this divergent theme. Bonds continued to unwind the bearish positioning and saw the US 10yr yield spike to a 2.16% low (from a high of 2.62% in March). Equities markets and credit markets continue to ride the liquidity wave and posted a strong month. We had a positive month with all of the flagship portfolios outperforming their respective benchmarks.

Jam tomorrow…

Over the last few months we have been questioning whether the global reflation trade is all its trumped up to be (pun intended). The optimistic theme has been run with hard by the market due to its bias to be optimistic after a disappointing 2014 and 2015 for the global economy. The upswing, kick started by an unprecedented expansion of credit in China, which rippled through every market, has been supported by enormous Quantitative Easing (QE) from both the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan. In this newsletter I do a deep-dive on China to see what we can learn about its potential growth path from the way it’s managing a number of increasingly conflicting financial market indicators.

The three liquidity factors above have driven risk markets strongly higher, pretty much ignoring the considerable amount of political risk that we’ve lived through and how much of it is on the horizon. Along with the market’s strong up-move we’ve seen consumer confidence, business confidence and manufacturing surveys across the globe accelerating to levels we hadn’t seen in years. This promise of continuing acceleration of GDP growth in 2017 was expected to push inflation higher than the oil rebound had already caused. Central bankers were taking note, with the Fed and the ECB talking about a better environment, seemingly looking to build on the confidence that was already permeating through the economy. With this optimism comes interest rate hikes, bringing with them higher bond yields. The optimism and continued QE would mean even higher equity markets and tighter credit spreads – further perpetuating the virtuous cycle.

It’s not supposed to happen like this…

To be clear this is all well and good if growth follows through on its promise, but if it doesn’t the thesis must change. So we are watching and waiting for the real economic data (the ‘hard’ data as I wrote about last month) to accelerate to meet with the forward looking surveys (the ‘soft’ data). Unfortunately a number of roadblocks towards achieving this were hit in late April and early May, denting the reflation story somewhat. The first is a quarterly US GDP growth outturn that was the worst recorded in three years, but more worrying is the second, which is that the ‘soft’ data looks to have peaked before growth has even started to accelerate.

The US first quarter advance GDP printed at 0.7% annualised, which was poor even for the traditionally depressed first quarter results. The Atlanta Fed “GDP Now” measure was a good lead on this print, with high consensus expectations showing that economists were clearly following the survey data. The big disappointment didn’t really shift markets, which are following the usual trend of looking through to the second and third quarter in the US for the big uplift to growth. As always the work is cut out for those quarters as with such a low first quarter print, it makes the required numbers for the rest of the year even higher to hit the consensus 2.2% GDP growth expectations for CY2017. To be fair, the good result for construction does bode well for future quarters, but it is still a large step to a decent yearly growth rate.

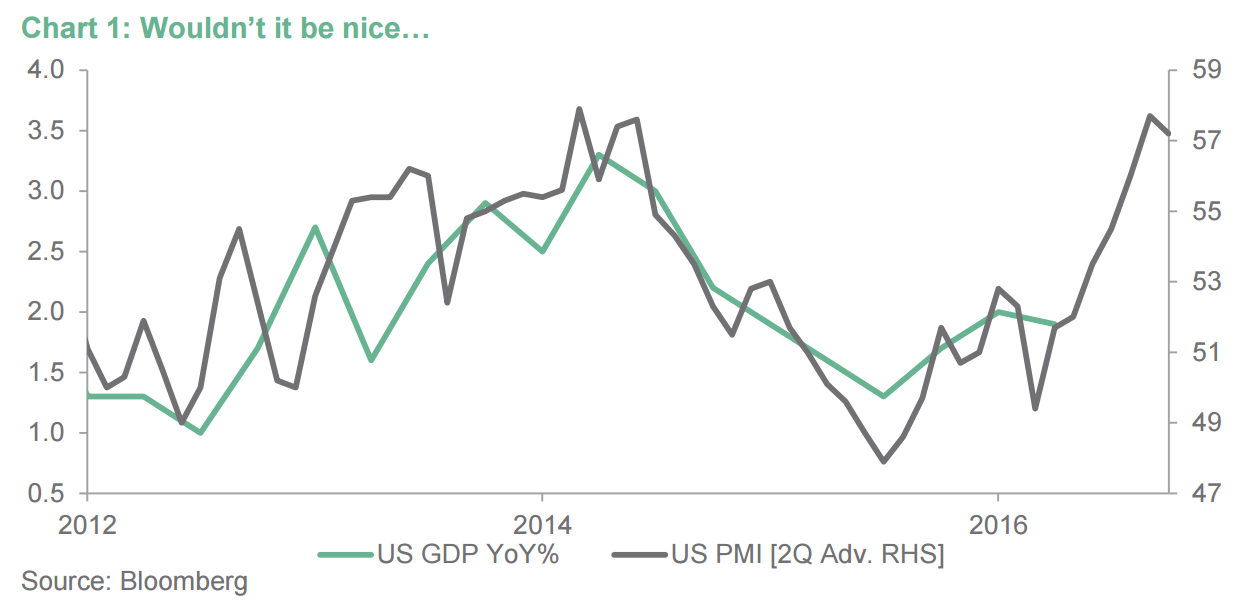

As regards the soft data, one of the most watched macroeconomic indicators in the world, the US ISM manufacturing survey, has been pointing towards some big quarterly growth numbers for quite a while. Operating with a two quarter lag and using the correlation of the last few years, the uplift in this manufacturing survey is pointing towards US GDP running at www.btim.com.au 3 roughly 3. 5%. The problem is that the ISM index is already starting to turn down as at the last print in early May. This print corroborates with the regional manufacturing surveys so it is unlikely to be an aberration.

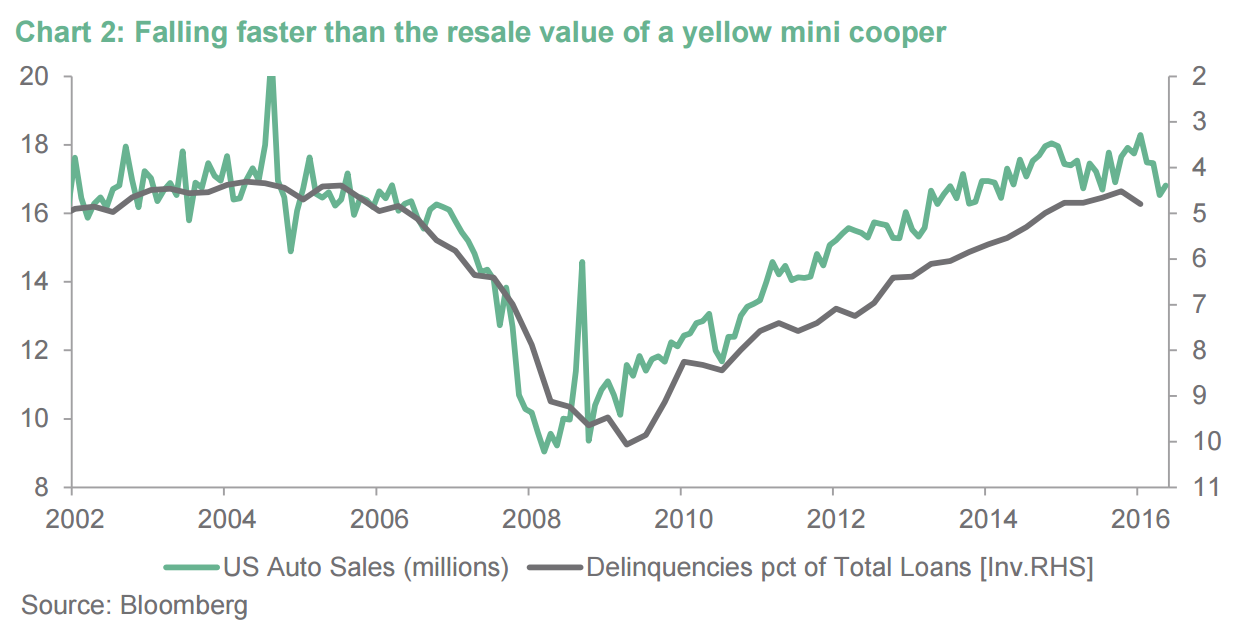

The new lower print points towards US GDP of just over 2.5%. While decent and above trend it is hardly a ‘reflation’; yearly growth is running at 1.9% now and has averaged 2.2% over the last three years. This is where a helpful Trump administration could and should build on this base by encouraging investment through any mix of incentives, but the chance of that is looking bleaker by the day. The low first quarter GDP print was due to an incredibly weak consumer, which will likely bounce in the coming quarters. However the magnitude of the bounce is questionable given we’ve seen auto sales crash 8% already this year, following the trend higher in auto loan delinquencies and a bloodbath in retail.

Given that most retail bankruptcies and hence store closures happen in the first part of the year after the last gasp that Christmas affords, 2017 is on track to have the most store closures since the GFC. A large part of the explanation is structural due to internet shopping, but store closures have very real effects on jobs and commercial property valuations, causing banks to pull back lending in that area. Stories like this aren’t supportive of an economy that is trying to break free from the low-growth trap left behind by the GFC.

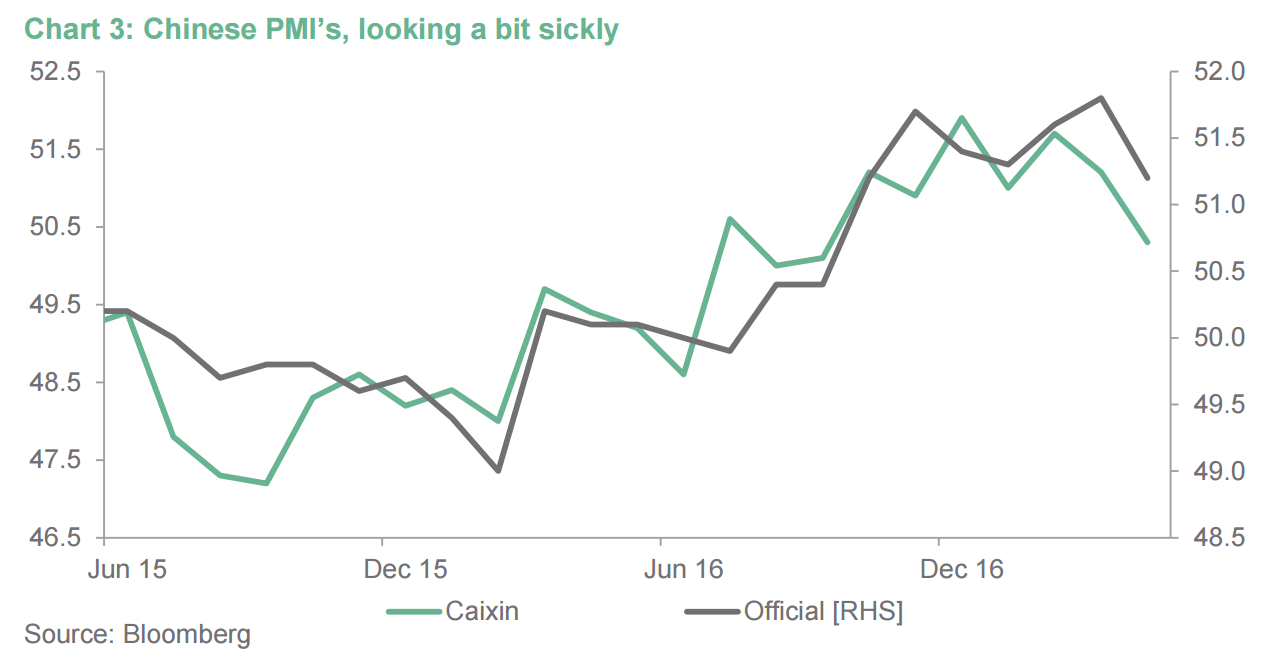

The fall in manufacturing surveys in the US doesn’t happen in a vacuum however, and as I wrote about last month the manufacturing surveys of all the different regions are highly correlated as we live in the era of globalisation (much to the dismay of Mr Trump et. al.). The two main Chinese PMI figures have also come in on the low side for May, disappointing not only market expectations but with outright falls in the absolute level of each index.

China, at an inflection point?

I have written in the last couple of newsletters about the profile of growth in China, which has been slowing since about the turn of the year. The slower pace of credit growth has seen the contribution to GDP from infrastructure investment slow materially, which means we’ve probably already seen the top in GDP growth, after a fairly lofty 7.1% for the first quarter. That said, property and private investment in our opinion will pick up the baton in the second half of the year giving Chinese growth (and perhaps world growth) a second wind. This further investment will however require even more credit, even if it is credit that’s going to better capitalised private companies over troublesome state owned enterprises. More credit means more leverage, and with the Chinese economy on its way to 300% debt to GDP ratio by 2019, this amount of leverage in an economy that doesn’t have a fully developed financial system is going to result in some issues.

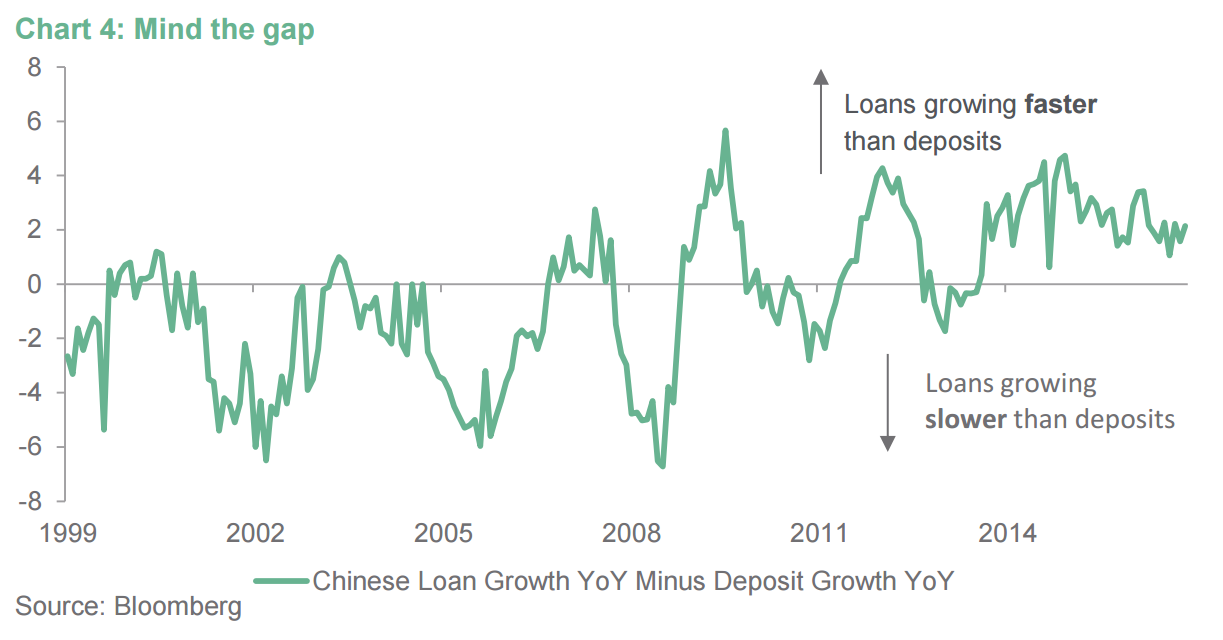

Huge debt means equally huge bank balance sheets. Huge bank balance sheets need to be funded, whether that is through bank deposits, long-term or short-term wholesale funding. The demand for funding from the market has skyrocketed since the GFC as bank loan growth has surpassed deposit growth since 2011, with the exception being one brief period during 2013 after there was a significant recovery in GDP growth from 7.5% to 8.1%. Unsurprisingly, this uplift in growth was from a burst in loan growth in the prior year. The cumulative funding gap to the banking sector increased by roughly 2% per year, leaving a 10% gap in funding, when total bank assets come in at just under $34 trillion. That is a very meaningful funding gap.

Scarily, the Chinese banking system is now the biggest in the world in USD terms ($34 trillion), overtaking the European banking system in late 2016, clocking in at nearly 3 times the size of its economy. For reference, the US banking system is only $7 trillion (only c.40% of the economy size). It also grew just under 35% over 2015 and 2016 in Yuan terms. Since China doesn’t have a bond market the depth of either the US or Europe, it has to rely heavily on the banking system for credit creation. It also has Wealth Management Products (WMPs) that total roughly $4 trillion, which are off balance sheet and the source of higher return (and presumably higher risk) credit exposures with even more leverage.

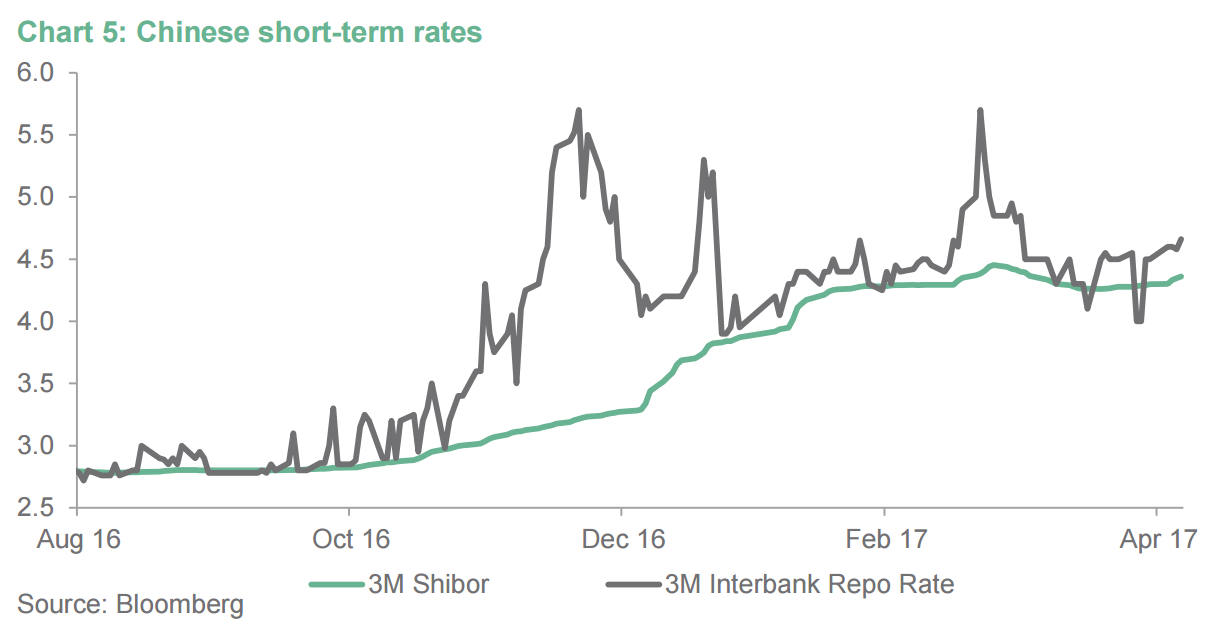

More recently a surge in outflows of deposits by foreign corporations has placed further strain on funding for the banking system, causing 3 month interbank rates to rise significantly at the end of 2016, from a low of 2.80% to a steady 4.34%. This is a persistent rise of more than 1.50%, doubling the PBOC’s underlying deposit rate. Be in no doubt, a funding squeeze is currently in play, a result of a massive growth in loan assets at the same time as deposits have failed to grow at a fast enough pace to cover. A situation like this is guaranteed to happen when you are growing credit by more than the economy, forcing the banks to search elsewhere to fund the gap, and generally this search has to happen overseas. When you have to search too hard, rates have to rise to attract that capital. The greater the funding gap and the greater the perceived risk, the greater the premium required.

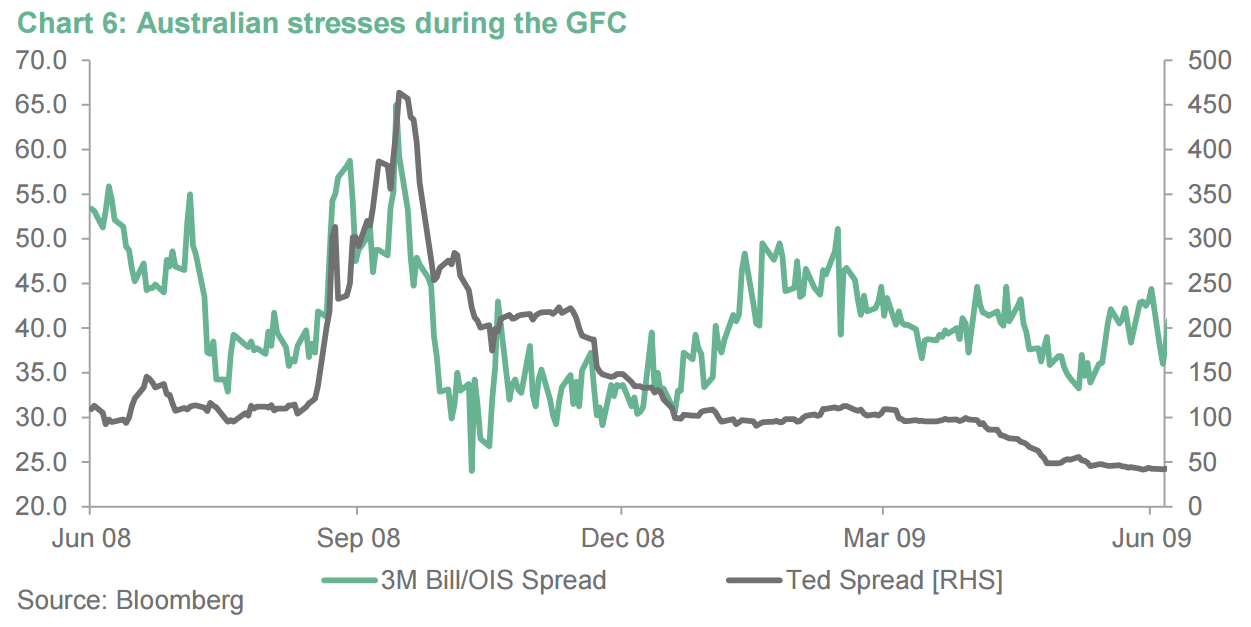

Developed market financial institutions are old hats at funding their expansions by reaching overseas. The Icelandic, Irish, Spanish and even Australian banks were the most successful at this strategy pre-GFC, growing their banking systems to many multiples of their respective economies. But this degree of rise in funding rates isn’t something that happens in developed financial markets, even at the worst of times. During the worst of the GFC (September-October 2008), short-term funding rates for banks increased in magnitude significantly but this was solely due to the fact the financial system was in an existential crisis at the time, with investors not knowing if a bank would make it through the night.

At the worst of it, Australian bank short-term funding rates increased by only 0.3% and while the US experience was far worse (with rates exploding by 3% for some of the lower tier banks), this extraordinary period only lasted for less than a month. Further, these higher funding costs rarely hit the banks as they did most of their borrowing from central bank emergency facilities, rather than from the interbank market. In contrast, funding spreads in China have widened by emergency levels, and have maintained those levels for nearly six months now, while the banks are actually paying these elevated levels to source funding. Yet there is no panic or concern visible in wider markets about this funding squeeze. If funding spreads blew out this much in the Australian market, the stability of our financial institutions would be questioned immediately.

Left a bit, right a bit, left a bit, full steam ahead

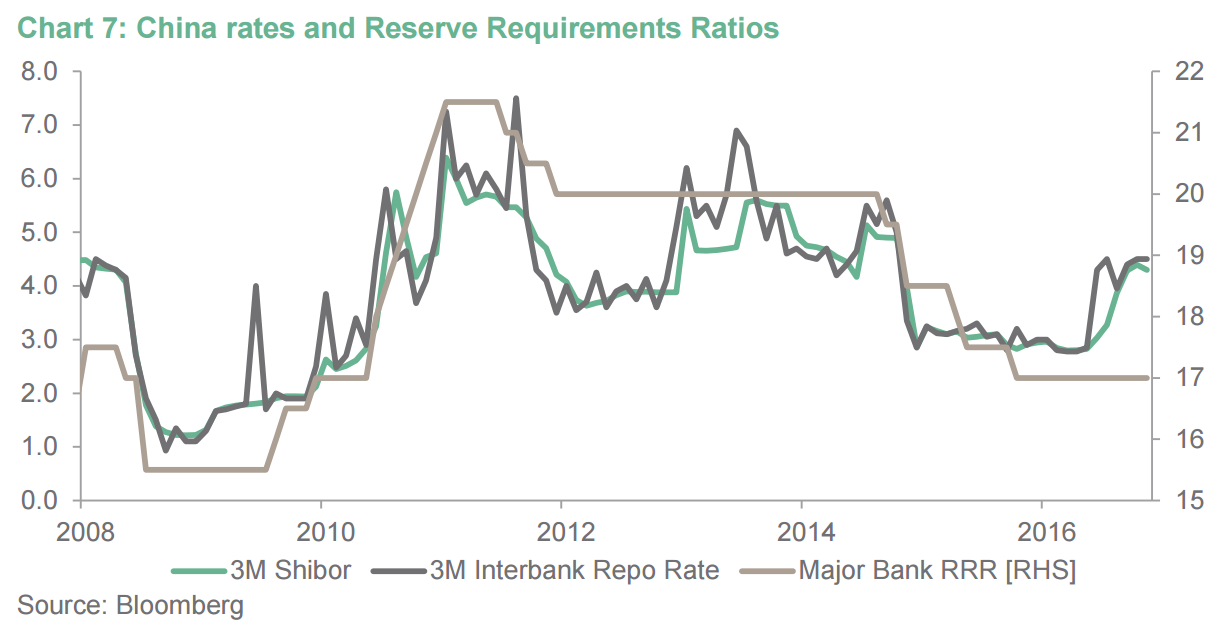

However, it is unlikely that these pricing signals morph into a full-blown crisis. This is thanks to the control that the leadership and the PBOC have over all aspects of the financial system, as well as the distinct lack of ways to actually make a direct bet on the failure of a bank. The charts above show that it isn’t the first time that this has happened either. Taking a longer term look at interbank funding rates shows that these rates can be highly volatile, with chart 7 below showing the spread to PBOC lending rates rather than the absolute borrowing rate. The chart also contains the Required Reserve Ratio (RRR). This is a ratio set by the PBOC which determines the reserves required to be kept at the central bank, and acts as a leverage limit on the banking system. Increasing the RRR should restrict the supply of credit to the economy, while reducing the RRR should encourage credit expansion. In the past this has been used to loosen monetary conditions when growth was waning, and as a tool to encourage economic reform by lifting the RRR. The fall in the RRR during 2015, a year of very poor economic growth, hinted at the leadership’s desire to kickstart credit as a growth engine once again.

These moves to the RRR also resulted in lower funding costs, as captive liquidity was immediately released into the market. Its payback is only being felt now with the rise in funding costs causing a slowdown in credit growth. A further RRR cut by the PBOC may alleviate some of these issues, but other limits are now being bumped up against, such as loan-to-deposit ratios. Obviously these rules can be changed (and are highly likely to change in order to avert a disaster), but right now they dictate the constraints the banking system operates under. More importantly to the leadership, lowering the RRR sends mixed signals on the ultimate goal of economic reform and hence the option is being left off the table.

Without the option of fixing the problem permanently with the RRR, the PBOC have resorted to expanding their use of an alphabet soup of liquidity facilities. These are aimed at ironing out the hiccups in interbank liquidity and essentially providing emergency funding to the banks that need it because of short-term funding issues. Once again, if these facilities were being used as regularly as they are in China in any other developed market there would be mass panic with equity investors dumping stocks, bond investors would stop rolling their exposures and short-term money market rates would cause a wider reaching liquidity crisis in the banking system. However, the rules are different in China, with total trust in the leadership to continue to manipulate any market necessary being the primary factor.

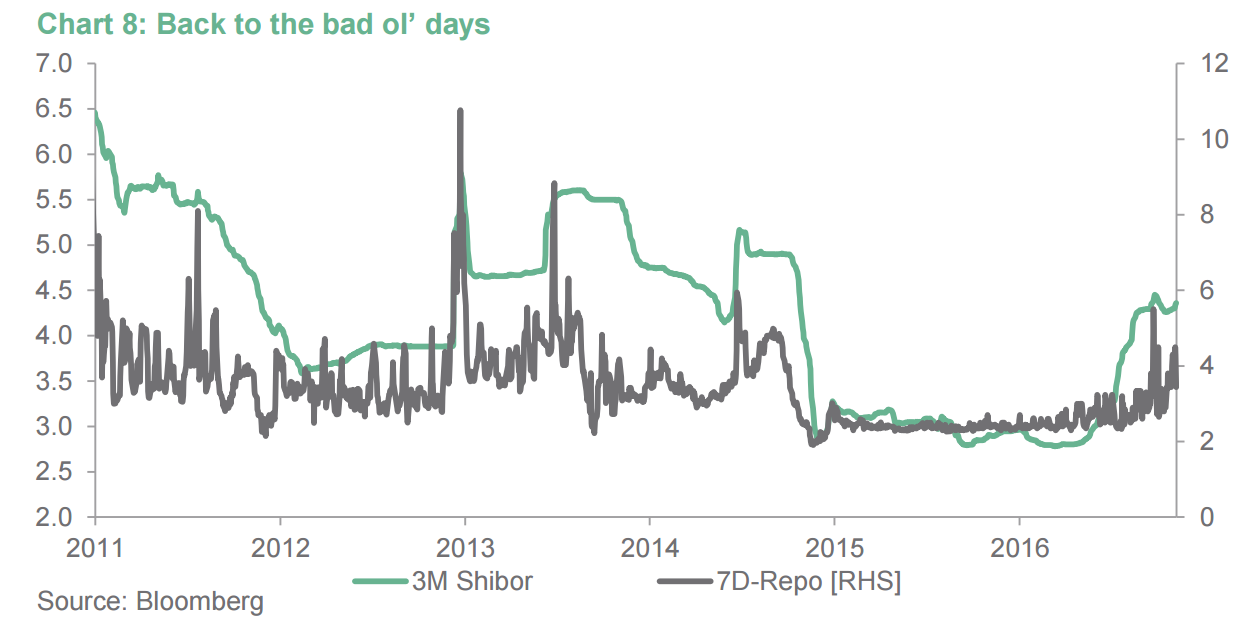

The best measure of liquidity issues is the 7 day repo rate. The more volatile this indicator (i.e. the more that it spikes), the more likely the PBOC will have to intervene with open market operations or provide liquidity through any number of facilities.

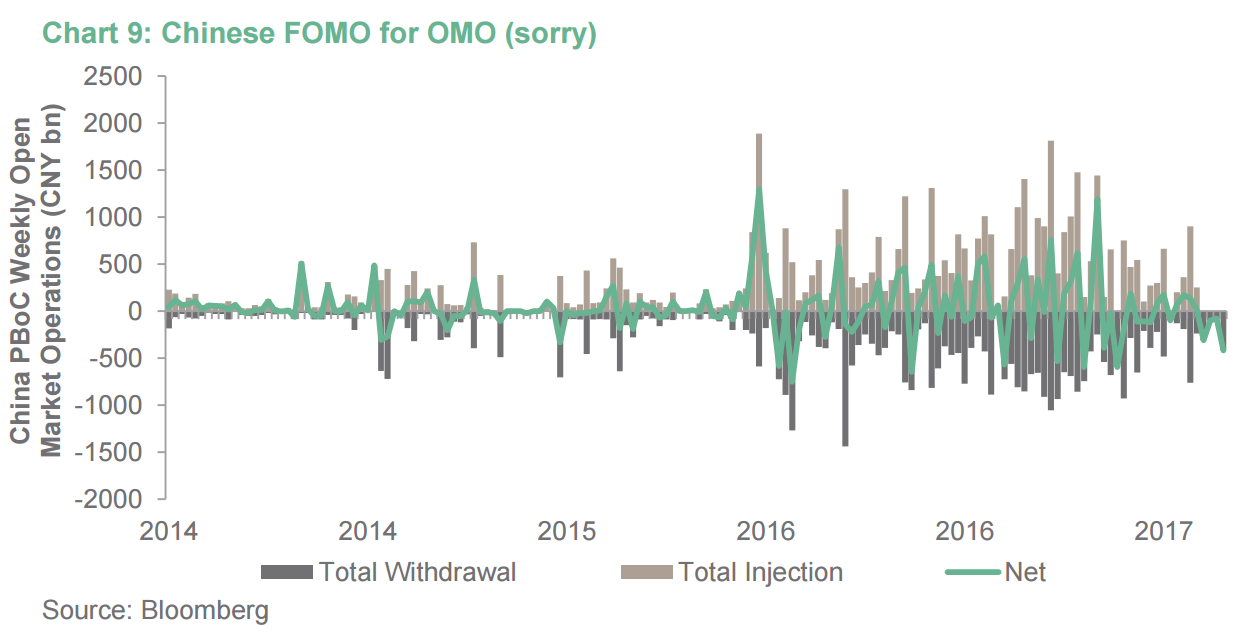

2015 and 2016 both saw low volatility in the 7 day repo rate, the sign of a well-functioning market. Along with this there was a low funding rate for banks (once again shown above by the 3 month interbank lending rate), and this was all probably a function of the large reduction in the RRR over the whole of 2015, releasing liquidity and taking pressure off the banks. Once credit growth kicked off again in late 2015 and the RRR was not dropped any further, open market operations started again, picking up in intensity toward the end of 2016 when funding rates started to increase as shown in chart 9.

The narrative being spouted for this intervention has been one of reform, with China bulls putting forward these hiccups as a necessary evil when trying to reduce leverage in the system. Those Wealth Management Products (WMPs) I spoke about before are big buyers of short-term paper of the banks, acting as a large funding source. To get the returns necessary for the higher returns promised with these products, leverage once again is the answer. Investing in bank and corporate bonds is done on a leveraged basis by lending out these securities to buy some more. This became such a widespread activity that it was feared that a small rise in interest rates would be enough to send some products bust just because of the degree of leverage. This already occurred in 2016 with stories of small financial institutions getting into trouble because of rising interest rates. In an attempt to curb this sort of behaviour, the PBOC has been allowing the market to suffer liquidity issues and restrict liquidity to non-bank institutions, leading to a bifurcation between bank and non-bank levels of stress.

The fact that it isn’t so much the proper banking system affected by these frequent liquidity disruptions should mean that everything is fine, right? Well we would argue that while the banking system may not be clamouring for liquidity, their funding costs have most definitely been going up because while they may not be in the firing line of PBOC policy, their key investors are. Add this to deposit outflow and it’s no wonder funding rates have jumped 1.5%.

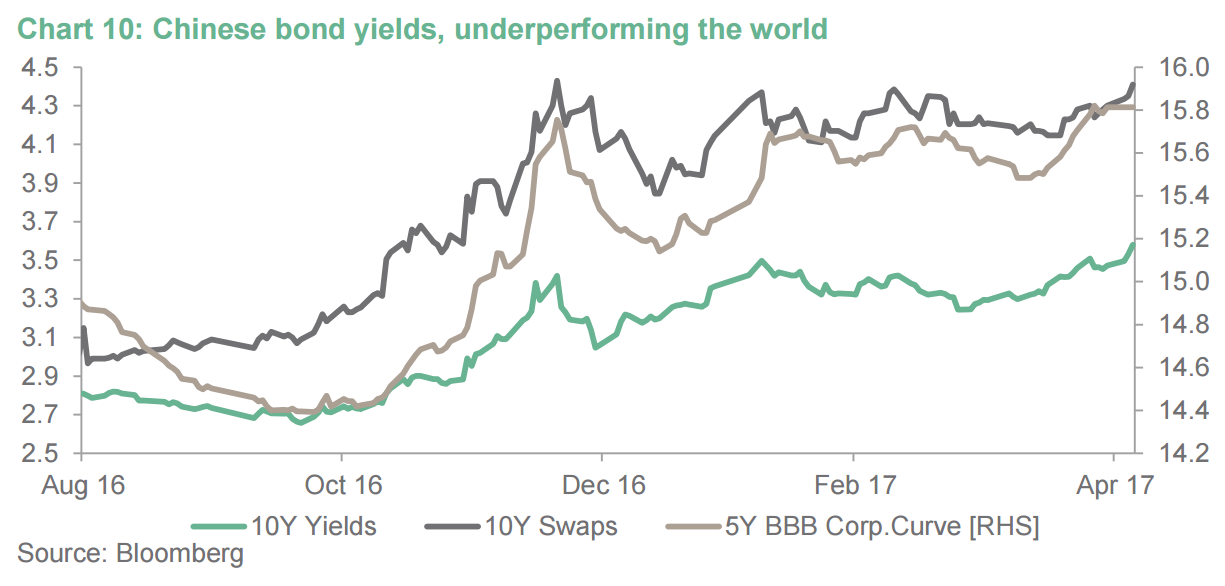

The targeting of leveraged institutions has had effects on other asset classes too, namely government bonds and other corporate credit. Chinese 10-year government bonds have made new highs in yield while the US has the gone the other way, remaining as an outlier. We’ve seen the same being reflected in swap rates and corporate credit which is at new highs in outright interest rates and wides in spread terms as well. Not great news for an economy as indebted as this one. Rising interest rates reduce corporate profits and consumption and while this may be the market operating rationally in light of the huge increase in debt, it points towards far higher defaults in the future.

This is all a very bleak story, painting the picture of a financial system that would be on the precipice in the absence of a central bank that had so much power to patch over any issues. This is the last environment you’d expect a central bank to be hiking rates, especially given that inflation has collapsed to only 0.9% for the year, with only modest improvements in inflation from here expected. Sure, factory input prices have been rising aggressively but that is just because of commodity prices and that will turn very soon anyhow as we have seen the highs in commodities already. Despite this, the PBOC has been gradually raising interest rates over the year, with 20bps of hikes so far across a range of money market facilities and more expected. While inflation and the deleveraging story was cited, we think there are other issues forcing the PBOC’s hand here.

ina will always find itself in a position where its hand is forced on rates is because they continue to try and manage the currency and avoid significant depreciation while having a leaky capital account which still enables individuals and corporates to get their money out of the country. The more the US raises interest rates, the more pressure is placed on the attraction of offshore locations for capital, making it harder to keep the currency stable. China has gone down two routes to ensure the currency doesn’t devalue which is to raise interest rates and to further clamp down on the current account. A huge 7.1% economic growth rate in the first quarter certainly goes a long way to keep capital onshore as well, but when the environment does sour it will place more pressure on the PBOC to hike rates further to keep capital at home. Rising market interest rates have also helped to attract offshore funding for banks. Where else in the world can you get 4.3% for lending to a well rated bank for 3 months? This has all contributed to a result of zero capital outflows as per the official numbers in the last two months. A good story – for now.

Controlling the illusion or the illusion of control?

There is no doubt financial risks are rising in China. This is going to put further constraints on the ability of the leadership to reform the economy away from the ‘old economy’ of heavy industry towards consumption, as the noose of past debts tightens on the economy, siphoning more resources away just to service past debts. The issues with liquidity I have highlighted will place further strain on an already creaking system, struggling with a massive volume of debt.

Being bearish on the China story is getting old and multitudes of investors have been run over waiting for the big crash to happen: however, there is one difference this time around, and this is the reason we are becoming more cautious. For the first time in modern Chinese economic history, interest rate policy is been implemented like it is a real emerging market country, and this is deeply concerning. Throughout the last decade-and-a-half China has been classed as an emerging market, but it was seemingly big enough and dominant enough on the world stage that interest rate policy acted like a developed market. In this sense it was set for domestic growth and inflation reasons, not for external reasons. It seems now that the PBOC is hiking interest rates to manage the currency and capital outflows, rather than domestic inflation or financial system stability. All you have to do is ask Brazil or Thailand or Russia why having to do this can make life very difficult for the domestic economy.

Thank you, Yves.

This may explain the rush of Chinese “investment” out of China. I was at Canary Wharf (the former London docklands and since the turn of the century a new business district for readers who are not familiar with London) yesterday morning and was told of a new skyscraper to be built. Apparently, the apartments, beginning at £1m for one bedroom, have been sold off plan, mainly to Chinese “investors”.

The 20 acre development at Greenwich Peninsula, across the Thames from Canary Wharf adjacent to the O2, is being built by a developer called Knight Dragon.

They are the same people who built the Shard but this development is being paid for with Shanghai money: it’s easy to imagine innumerable ways sales at the Peninsula could be used to launder flight capital.

The first 4 or 5 apartment towers were topped out over the last winter.

Thank you, JSN.

I don’t know if this was the development that the persons I was talking to mentioned. I was at Frontispiece in Westferry, so the other direction.

Chinese money is also developing the riverside between the Wharf and airport.

I have been to Pan Peninsula, on Marsh Wall, for meetings as a contractor colleague leased there for a year. The tower is full of Singaporean families, usually students with their parents and progeny in tow. There is an oligarch with much younger model in tow resident there. We nickname him Jabba. My former colleague’s lease was terminated early to make way for a much better paying Singaporean student and family.

Chinese capital controls have tried to make a distinction between those shipping cash out for safety and ‘investors’. But I suspect this has just led to distortions rather than stopping money flows. It may make more sense to invest in the construction of a new building (business investment) rather than buying completed apartments up front (speculation). I’ve heard one story from a Chinese friend of someone in China seeking to buy a business in Europe for several million euro – he seems strangely uninterested on whether or not the business is any good. I suspect its just a cover for exporting money.

I’m curious that there is still a lot of Chinese money going into London property. Most Chinese seem to find Brexit incomprehensible and stupid. I suppose much of it could have been money already committed, or perhaps they see opportunities with a weakening sterling. I know one Chinese person (British citizen by marriage) who lives in Germany who is moving back to the UK – her income is mostly from rental properties in London, she fears being unable to survive if sterling drops too much relative to the euro.

It would seem then that China is not pivoting successfully to a consumption and services based economy, or at least not in any significant fashion. I know that Yves has referrenced labor unrest in China as it winds down inefficient state run enterprises, but I don’t see any reference to that aspect of an unhappy economy in the note. I wonder then if China could adopt aspects of MMT and truly retrench in a more nationalistic bent if faced with a real crisis?

I understand that China does import a great deal of raw materials and other goods, but this is deeply tied to it’s high export surplus and need to employ people in unprofitable industries. From my light observation, China seems to be wholly self-sufficient in ways that other crisis countries aren’t. China can make and grow just about everything it needs to continue running it’s economy. Could China create a government job guarantee for those being cast into unemployment during a crisis? Would it embark on a New Deal like pivot of social guarantees and jobs programs that might lift a larger swath of it’s population out of subsistence wages and poverty? I don’t see why not given that the government is heavily involved in planning most aspects of the economy and is most interested in propagating it’s control over said population. An economic crisis will not be good for the legitamacy of the Communist party.

Their ‘PLANNED” Economy and PBOC will make sure, it won’t happen! there will be a ‘sort’ of Extend & Pretend measures to satisfy the investors!

I’ve no inside knowledge or expertise, but as has been discussed before, the Chinese have had to face a choice with the ‘impossible trinity’ of a free floating currency, open capital flows and low interest rates. It looked for a while like the Chinese had decided that the ‘open capital flows’ part was the one to give. There have certainly been significant reductions thanks to changes in policy last year. But I wonder if creeping rises in interest rates is a sign that its not been successful enough and they need another tool. It might also be simply an attempt not to allow the markets second guess what they’ll do (not least because suspicions that there will be further capital controls may cause panic off-shoring).

I think its generally accepted that the Chinese will do what they have to do to keep the financial system stable, and they have far more control over internal workings than the US or Europe. But with debt leveraging so very high, it seems to me they are playing with fire in allowing a suggestion of rising interest rates. The Chinese banking system is so highly leveraged it would seem to me that a ‘black swan’ event could lead to events happening so rapidly the authorities just couldn’t react fast enough.

Its all speculation of course. As the article says, there have been Chinese bulls predicting imminent doom since the 1980’s (namely Gordon Chang). All have been proven wrong. But the authorities only have to make one big mistake for everything to spin out of control, there seems no real slack in the system, everything is tied together so tightly, bound together with loose credit.

“The Chinese have had to face a choice with the ‘impossible trinity’ of a free floating currency, open capital flows and low interest rates.” — PK

“[Peoples Bank of Chi]na will always find itself in a position where its hand is forced on rates is because they continue to try and manage the currency and avoid significant depreciation while having a leaky capital account which still enables individuals and corporates to get their money out of the country.” — David L-S

No one knows the timing. But China’s “break glass in case of fire” option remains pulling the plug on the dirty float and letting the yuan slide, probably at the worst possible moment when global markets already are roiled by evident distress and rumours of more distress.

Until that dark day, we can assume China’s banking boffins feel they have matters well in hand. :-)

I think it would have to be a very big emergency for China to break that glass. A fast falling Yuan is almost guaranteed to set off a huge flow of cash by any means out of the country. It will also set off inflation, something the CCP fears greatly – nothing will provoke riots in the street quicker in China than rises in the price of pork.

I would guess they would go all out for capital controls before they’d do that. That could mean a lot of abandoned construction projects around the world if the flow of yuan dries up.

That could mean a lot of abandoned construction projects around the world if the flow of yuan dries up.

The home town feeling is getting spread around.

“No slack in the system, tied together tightly …”

Verily the Chinese have constructed a Daemon of Their Own Design (Richard Bookstaber).

How does money and bank credit really work?

“…banks make their profits by taking in deposits and lending the funds out at a higher rate of interest” Paul Krugman, 2015.

Wrong.

The best way to think of it as borrowing your own money from the future.

When you get a loan the bank creates the money now, for you to spend today, in the future you make the repayments to pay back the money. The bank is back to square one and has collected interest for the service of lending you your own money from the future.

In the money supply, you get the instant hit as that money is created from the loan and that money is then removed as the repayments are made.

97% of money in the UK comes from bank credit and it is constantly being created and destroyed.

The BoE explanation:

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

The trick of the neoliberal era has been not to understand money and bank credit like Paul Krugman. Its success has really just been about bringing money from the future into today, today looks better but tomorrow is impoverished.

Margaret Thatcher was the first person to bring neoliberalism to the West and this is the debt fuelled ponzi scheme of the UK economy.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.53.09.png

Today has been good because we have been borrowing from tomorrow.

Greece enjoyed today until tomorrow came.

The ubiquitous neoliberal real estate boom has been one of the primary mechanisms for bringing money from the future forward to today. Today is good, tomorrow is not.

This is the underlying nature of debt:

Jam today, penury tomorrow

This is the neoliberal confidence trick, pulling money out of the future and spending it today.

Monetary theory has been regressing for one hundred years:

“The movement from the accurate credit creation theory to the misleading, inconsistent and incorrect fractional reserve theory to today’s dominant, yet wholly implausible and blatantly wrong financial intermediation theory indicates that economists and finance researchers have not progressed, but instead regressed throughout the past century. That was already Schumpeter’s (1954) assessment, and things have since further moved away from the credit creation theory.”

“A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence” Richard A. Werner

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521915001477

Today, mainstream economists don’t understand money and private debt is missing from today’s neoclassical economics due to the fictitious “financial intermediation theory”.

The neoliberal confidence trick occurs and no one can see it.

Apart from a few like Steve Keen who 2008 coming in 2005, his latest book “Can we avoid another financial crisis?” is worth reading and goes into the neoliberal confidence trick in more detail.

+1

until this is more widely understood the scam will continue. In the meantime it has produced so much debt that it may implode in on itself in spite of all the central bank abracadabra of recent years. The clock is ticking!

Neoliberalism was global and the global private debt is horrendous.

All money borrowed from the future, that made things look so good for a while.

Greece has already passed from the good today into the impoverished tomorrow.

The Euro-zone crisis stems for the main part from this ignorance of money and debt.

When it started interest rates were set low across the Euro-zone, interest rates plummeted at the periphery that had previously been treated as high risk. They bought forward their spending at the periphery and blew real estate bubbles in Spain, Ireland, Greece and Holland.

Holland has added massive incentives to keep its real estate bubble from bursting.

In a BBC documentary they were showing Greece after it blew up and what it had been like before. They had all been buying Porsche Cayennes on cheap credit and now there were loads going second hand.

The Central bank solutions are temporary in nature and in the breathing space they should have been working on real solutions but they haven’t.

The ECB and BOJ are pouring tons of QE into the global financial system to keep asset prices inflated for now.

The ECB is buying bonds at the periphery to keep interest rates down for now.

Temporary solutions to underlying permanent problems.

It’s a global disaster area.

agree, agree, agree, but when and how does this end? I have argued that it is the biggest pyramid scheme in history and when it blows, and it invariably will, it is going to be scary. As you note the BOJ and ECB are pumping lots of new “money” into the system so the entire thing is still in full Ponzi mode. And the Swiss National Bank is also issuing liability claims that never have to be paid, i.e. Swiss Francs, exchanging them for dollars and buying U.S. equities. They now own $80 billion in U.S. stocks which they bought with money conjured from nothing. And yet people still have faith in the central banks.

Huh? Banks can’t make money out of thin air, they have to have a source of funds to loan, and my understanding is that deposits are the largest, but not only source of funds. Banks make their profit on the spread between the interest paid for the source of funds, and interest received from loans. The bank does make a new deposit for the loan, but they still have to either pay interest on that deposit, or have the funds to cover the loan amount when the loan receiver spends the loan. How is Krugman wrong?

You do know about fractional reserve lending, right? How banks are legally allowed to lend out 10 times as much money as the amount that customers have deposited? (To use a simple ratio — actual fractional reserve requirements may vary.) That’s how they create money out of thin air. And the arcane ways that “investment” (i.e. “speculator”) banks have to amp that on steroids produce ratios closer to 100:1 of loans (speculation) vs. capital in hand.

I don’t say this to snark at you or be demeaning. The “quantum physics of banking” are obscure, deliberately, because people wouldn’t like it if they knew how shonky the basis of the system is. Not everybody is aware. It’s not taught in high school. If this is relatively new to you, I suggest watching an easy-to-understand but not sophomoric cartoon video titled “Money as Debt” by a Canadian bloke named Paul Grignon. Makes it clearer. Again, apologies if I’m telling you something you already know. Naked Capitalism’s comments are a haven from the sneering superiority tone of most website chatter, so I don’t want to come across as supercilious.

@b1daly and @Bukko Boomeranger – Banks do, in fact, create money “out of thin air.” They issue a loan to a creditworthy customer and deposit the proceeds into the borrower’s account, which is the act of creating money (loans create deposits). These funds do not “come from” anywhere. It is not a fractional reserve system. The bank is not required to have any particular level of reserves in order to make the loan. They acquire any necessary reserves after the fact.

See the paper by the BoE linked above by Sound of the Suburbs.

@b1daly

Banks create money form nothing and it is in fact IMPOSSIBLE to lend out someone’s deposit. You need to purge from your mind of what you think you know. As for the fractional reserve, money multiplier explanation of banking, it is highly misleading and some people believe this is intentional so as to obscure the true nature of banking. As for reserves requirements that is just more misdirection; many systems have zero reserve requirements in recognition that reserves are largely irrelevant in the overall scheme of things. Reserves are just “clearing certificates” that allow deposits to be transferred from one bank to another. The U.S. banking system created a massive bubble of credit/money that peaked in 2007 on a tiny sliver of reserves which totaled less than $50 billion at the time.

And deposits are nothing more than a special kind of bank debt that is tied into a sophisticated payment network the allows the deposits to be transferred from one bank to another using those clearing certificates. Just merge all the banks into one in your mind as a thought experiment and it should become more clear how it all works. The fact that deposits can be transferred tends to confuse the issue for most people. It is a practical issue that banks have to deal with vis a vis one another but irrelevant to the system as a whole.

Of course you may not believe any of us posting these types of explanation so please refer to the BoE paper referenced above.

The US banking system is much larger than this article suggests with $16 trillion in total assets. Plus gross notional derivatives exposure is 10’s of $trillions. Bank credit in the US is $12 trillion. I have read that a similar ratio of credit to total assets exists in the Chinese banking system. Since this is all credit ex nihilo, the state can step in any time it wishes and ‘fix’ losses. So the Chinese gov’t can create a controlled demolition by letting its banks and wealth management products sector fail or it can prop it up. Bottom line: if the Chinese want a crisis, they can have one with potentially global repercussions. The US did it about a decade ago. The US crisis resulted in greater concentration of power and wealth with diminished rights and prospects for citizens.

Likewise, the US could eliminate all of its public debt through controlling reserves or issuing zero interest treasury notes akin to the bills in your wallet.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/current/

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TLAACBW027SBOG

‘ However, the rules are different in China, with total trust in the leadership to continue to manipulate any market necessary being the primary factor’.

Is this any difference in PBOC compared to CB ers in USA, Europe and Japan?

Extend & Pretend game has been working so far and ‘may’ continue for several years, just like Japan!

Very low interest rate with very low growth, supported periodically by CBers?

History rhymes. Then Japan. Today China. Ages of debt and a surging dollar will ultimately lead to a chinese currency-crisis masterminded by an US Plaza Accord 2.0. Dollartop 2018? Dx at 130-140? What will drive the dollar? More capitalflow……… asset-inflation.

Will the chinese leadership hide their losses as did the japanese zaibatsus? If so there will be a long and slow ride down for the world economy.

How not to get yourself in this mess in the first place.

For future reference:

The banking paradox:

1) Bankers want to keep the privilege of creating money.

2) Bankers want to be free to do what they want.

You can have one or the other, not both.

What happens when you have both?

We tried it and that was the end of the once vibrant global economy

http://www.whichwayhome.com/skin/frontend/default/wwgcomcatalogarticles/images/articles/whichwayhomes/US-money-supply.jpg

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

“Although commercial banks create money through lending, they cannot do so freely without limit. Banks are limited in how much they can lend if they are to remain profitable in a competitive banking system.”

The limit for money creation holds true when banks keep the debt they issue on their own books.

The BoE’s statement was true, but is not true now as banks can securitize bad loans and get them off their books.

NINJA mortgage anyone?

very good point that few people understand; banks became “debt pumps” with the advent of securitization. Of course economists haven’t figured this out yet so it may be another 20 years before this becomes conventional knowledge.

Under this scenario, the banks are still limited by market conditions. To make money like this, they have to find and qualify borrowers. And they have to find buyers for the loans. It’s not an infinite merry-go-round, if the system is pushed too hard, the music will stop, as we saw in GFC.

I would be interested to know how much this has become industry practice for loans outside of mortgages. It seems like it would be harder to create securities out of bundled loans that were more heterogeneous, like business loans.

yes banks may be limited by “market conditions” but market conditions are hardly fixed and can expand or contract based on the prevailing psychology. Nobody is suggesting that it is an “infinite merry-go-round” but when certain types of thinking set it it can get way out of balance. Business loans are routinely turned into something called collateralized loan obligations so securitization touches on almost all aspects of bank lending.