By Jason Smith, a physicist who messes around with economic theory. He graduated from the University of Texas at Austin with a degree in math and a degree in physics, and received his Ph.D. from the University of Washington in theoretical physics. Follow him on Twitter: @infotranecon. Originally published at Evonomics

The inspiration for this piece came from a Vox podcast with Chris Hayes of MSNBC. One of the topics they discussed was which right-of-center ideas the left ought to engage. Hayes says:

The entirety of the corpus of [Friedrich] Hayek, [Milton] Friedman, and neoclassical economics. I think it’s an incredibly powerful intellectual tradition and a really important one to understand, these basic frameworks of neoclassical economics, the sort of ideas about market clearing prices, about the functioning of supply and demand, about thinking in marginal terms.

I think the tradition of economic thinking has been really influential. I think it’s actually a thing that people on the left really should do — take the time to understand all of that. There is a tremendous amount of incredible insight into some of the things we’re talking about, like non-zero-sum settings, and the way in which human exchange can be generative in this sort of amazing way. Understanding how capitalism works has been really, really important for me, and has been something that I feel like I’m a better thinker and an analyst because of the time and reading I put into a lot of conservative authors on that topic.

Putting aside the fact that the left has fully understood and engaged with these ideas, deeply and over decades (it may be dense writing, but it’s not exactly quantum field theory), I can hear some of you asking: Do I have to?

The answer is: No.

Why? Because you can get the same understanding while also understanding where these ideas fall apart ‒ that is to say understanding the limited scope of market-clearing prices and supply and demand – using information theory.

Prices and Hayek

Friedrich Hayek did have some insight into prices having something to do with information, but he got the details wrong and vastly understated the complexity of the system. He saw market prices aggregating information from events: a blueberry crop failure, a population boom, or speculation on crop yields. Price changes purportedly communicated knowledge about the state of the world.

However, Hayek was writing in a time before information theory. (Hayek’s The Use of Knowledge in Society was written in 1945, a just few years before Claude Shannon’s A Mathematical Theory of Communication in 1948.) Hayek thought a large amount of knowledge about biological or ecological systems, population, and social systems could be communicated by a single number: a price. Can you imagine the number of variables you’d need to describe crop failures, population booms, and market bubbles? Thousands? Millions? How many variables of information do you get from the price of blueberries? One. Hayek dreams of compressing a complex multidimensional space of possibilities that includes the state of the world and the states of mind of thousands or millions of agents into a single dimension (i.e. price), inevitably losing a great deal of information in the process.

Information theory was originally developed by Claude Shannon at Bell Labs to understand communication. His big insight was that you could understand communication over telephone wires mathematically if you focused not on what was being communicated in specific messages but rather on the complex multidimensional distributions of possible messages. A key requirement for a communication system to work in the presence of noise would be that it could faithfully transmit not just a given message, but rather any message drawn from the distribution. If you randomly generated thousands of messages from the distribution of possible messages, the distribution of generated messages would be an approximation to the actual distribution of messages. If you sent these messages over your noisy communication channel that met the requirement for faithful transmission, it would reproduce an informationally equivalent distribution of messages on the other end.

We’ll use Shannon’s insight about matching distributions on either side of a communication channel to match distributions of supply and demand on either side of market transactions. Let’s start with a set of people who want blueberries (demand) and a supply of blueberries. These represent complex multidimensional distributions based on all the factors that go into wanting blueberries (a blueberry superfood fad, advertising, individual preferences) and all the factors that go into having blueberries (weather, productivity of blueberry farms, investment).

In place of Hayek’s aggregation function, information theory lets us re-think the price mechanism’s relationship with information. Stable prices mean a balance of crop failures and crop booms (supply), population declines and population booms (demand), speculation and risk-aversion (demand) — the distribution of demand for blueberries is equal to the distribution of the supply of blueberries. Prices represent information about the differences (or changes) in the distributions. And differences in distributions mean differences in information.

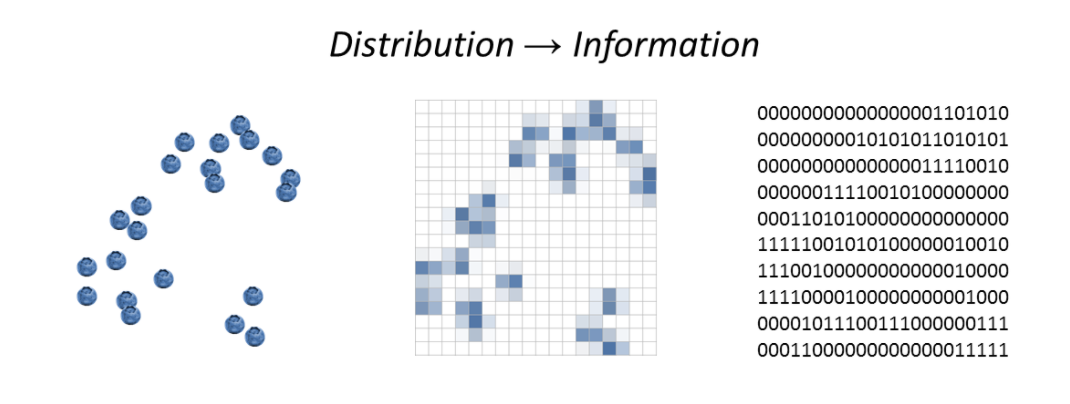

Imagine you have blueberries randomly spread over a table. If you draw a grid over that table, you could imagine deciding to place a blueberry on a square based on the flip of a coin (a 1 or a 0). That is one bit of information. Maybe for some of the squares, you flip the coin two or more times. That’s two or more bits.

Now say you set up a distribution of buyers on an identical grid using the same process. If you flipped more coins for the buyers than the blueberries on the corresponding squares, that represents a difference in information (and likely an excess demand).

There can be an information difference even if there’s no difference between the results of the coin flips. For example, you can get one blueberry on a square because you flipped a coin once and it came up heads or you flipped a coin twice and it came up heads once and tails once. However as the number of coin flips becomes enormous in a huge market, the difference between the results of the coin flips (excess supply or demand) will approximate the difference in the information in the coin flips. This is an important point about when markets work that we will come back to later. It is also important to note that these are not just distributions in space, but can be distributions in time. The future distribution of blueberries in a functioning market matches the demand for blueberries, and we can consider the demand distribution information flowing from that future allocation of blueberries to the present through transactions.

Coming back to a stable equilibrium means information about the differences in one distribution (i.e. the number of coin flips) must have flowed (through a communication channel) to the other distribution via transactions between buyers and sellers at market prices. We can call one distribution D and the other S for supply and demand. The price is then a function of changes (Δ or “delta”) in D and changes in S:

p = f(ΔD, ΔS)

Price is a function of changes in demand and changes in supply. That’s Economics 101. But what is the function describing the relationship? We know that an increase in S that’s bigger than an increase in D generally leads to a falling price, while an increase in D that is bigger than the increase in S generally leads to a rising price. If we think in terms of distributions of demand and supply, we can try

p = ΔD/ΔS

for our initial guess. Instead of a aggregating information into a price, which we can’t do without throwing away information, we have a price detecting the flow of information. Constant prices tell us nothing, but price changes tell us information has flowed (or been lost) between one distribution and the other. And we can think of this information flowing in either space or time if we think of the demand distribution as the future allocation of supply.

This picture also gets rid of the dimensionality problem: the distribution of demand can be as complex and multidimensional (i.e. depend on as many variables) as the distribution of supply. The single dimension represented by the price now only measures the single dimension of information flow.

Marginalism and Supply and Demand

Chris Hayes also mentions marginalism. It’s older than Friedman or Hayek, going back at least to William Jevons. In his 1892 thesis, Irving Fisher tried to argue (crediting Jevons and Alfred Marshall) that if you have gallons of one good A and bushels of another good B that were exchanged for each other, then the last increment (the marginal unit) was exchanged at the same rate as A and B, i.e.

ΔA/ΔB = A/B

calling both sides of the equation the price of B in terms of A. Note that the left side is our price equation above (p = ΔD/ΔS), just in terms of A and B (you could call A the demand for B). In fact, we can get a bit more out of this equation if we say

pₐ = ΔA/ΔB = A/B

We add a little subscript a to remind us that this is the price of B in terms of A. If you hold A constant and increase B (supply), the price goes down. For fixed demand, increasing supply causes prices to fall – a demand curve. Likewise if you hold B constant and increase A, the price goes up – a supply curve. However if we take tiny increments of A and B and use a bit of calculus (ΔA/ΔB becomes dA/dB) the equation becomes a differential equation that can be solved. In fact, it is one of the oldest differential equations to be solved (by Bernoulli in the late 1600s). However, the solution tells us that A is linearly proportional to B. It’s a quite limited model of the supply-demand relationship.

Fisher attempts to break out of this limitation by introducing utility functions in his thesis. However thinking in terms of information can again help us.

If we think of our distribution of A and distribution of B (like the distribution of supply and demand), each “draw” event from those distributions (like a draw of a card, a flip of one or more coins, or roll of a die) contains I₁ information (a flip of a coin contains 1 bit of information) for A and I₂ for B. If the distribution of A and B are in balance (“equilibrium”). Each draw event from each distribution (a transaction event) will match in terms of information. Now it might cost two or three gallons of A for each bushel of B, so the number of draws on either side will be different in general, but as long as the number of draws (n) is large, the total information from those draws will be the same:

n₁ · I₁ = n₂ · I₂

Rearranging, we have

n₁ · (I₁ / I₂) = n₂

We’ll call I₁/I₂ = k (for reasons we’ll get into later) so that

k · n₁ = n₂

Now say the smallest amount of A is ΔA and likewise for B. One bushel or one gallon, say. That means

n₁ = A/ΔA

n₂ = B/ΔB

i.e. the number of gallons of A is the total amount of A divided by 1 gallon of A (i.e. ΔA). Putting this together and rearranging a bit we have

ΔA/ΔB = k · A/B

This is just Fisher’s equation again except there’s our coefficient k in it expressing the information relationship, making the solution to the differential equation mentioned above a bit more interesting than being linearly proportional — now log(A) = k log(B) + b, where b is another constant. The supply and demand relationship found by holding either A or B constant and varying the other is also more complex than the one you obtain from Fisher’s equation (it depends on k). It’s essentially a more generalized marginalism where we no longer assume k = 1. But there’s a more useful bit of understanding you get from this approach that you don’t get from simple price signaling. What we have is information flowing between A and B, and we’ve assumed that information transfer is perfect. But markets aren’t perfect, and all we can really say is that the most information that can get from the distribution of A to the distribution of B is all of the information in the distribution of A. Basically

n₁ · I₁ ≥ n₂ · I₂

Following through with this insight in the derivation above, we find

p = ΔA/ΔB ≤ k · A/B

Because the information flow from A can never be greater than A’s total information, and will mostly be less than that total, the observed prices in a real economy will most likely fall below the ideal market prices. Another way to put it is that ideal markets represent a best-case scenario, one out of a huge space of possible scenarios.

There’s also another assumption in that derivation – that the number of transaction events is large, as we mentioned before. So even if the information transfer was ideal, the traditional price mechanism only applies in markets that have a large volume of trade. That means prices for rare cars or salaries for unique jobs likely do not represent accurate information about the underlying complex multidimensional distributions of market supply and demand. Those prices are in a sense arbitrary. They might represent some kind of data (about power, privilege, or negotiation skills), but not necessarily information about the supply and demand distributions or the market allocation of resources. In those cases, we can’t really know from the price alone.

Another insight we get is that supply and demand doesn’t always work in the simple way described in Marshall’s diagrams. We had to make the assumption that A or B was relatively constant while the other changed. In many real world examples we can’t make that assumption. A salient one today is the (empirically incorrect) claim that immigration lowers wages. A naive application of supply and demand (increased supply of labor lowers the price of labor) ignores the fact that more people means not just more labor, but more people to buy goods and services produced by labor. Thinking in terms of information, it is impossible to say that you’ve increased the number of labor supply events without increasing the number of labor demand events, so you must conclude A and B must both change. More immigration means a larger economy; the effect on prices or wages does not simply follow from supply and demand based on a population increase.

Instead of the simplified picture of ideal markets and forces of supply and demand, we have the picture advocates on the left (and to be fair most economists) try to convey of not only market failures and inefficiency but more complex interactions of supply and demand. Instead of starting with the best-case scenario, we start with a huge space of possible scenarios — all but one of them less-than-best.

However, it is also possible through collective action to mend or mitigate some of these failures. We shouldn’t assume that just because a market spontaneously formed or produced a result, that it is working optimally, and we shouldn’t assume that because a price went up either demand went up or supply went down. In that case, the market might have just gotten better at detecting information flow that was already happening. We might have gone from non-ideal information transfer where n₁ · I₁ ≥ n₂ · I₂ to something closer to ideal where n₁ · I₁ ≈ n₂ · I₂, meaning the observed price got closer to the higher ideal price.

The equations above were originally derived a bit more rigorously by physicists Peter Fielitz and Guenter Borchardt in a paper published in 2011 titled “A generalized concept of information transfer” (there is also an arXiv preprint). The paper includes both the ideal information transfer (information equilibrium) and non-ideal information transfer scenarios. They call the coefficient k the information transfer index. As they state in their abstract, information theory provides shortcuts that allow one to deal with complex systems. Fielitz and Borchardt primarily had natural complex systems in mind, but as we have just seen, the extension to social complex systems — especially pointing out the assumptions necessary for markets to function — is straightforward.

The market as an algorithm

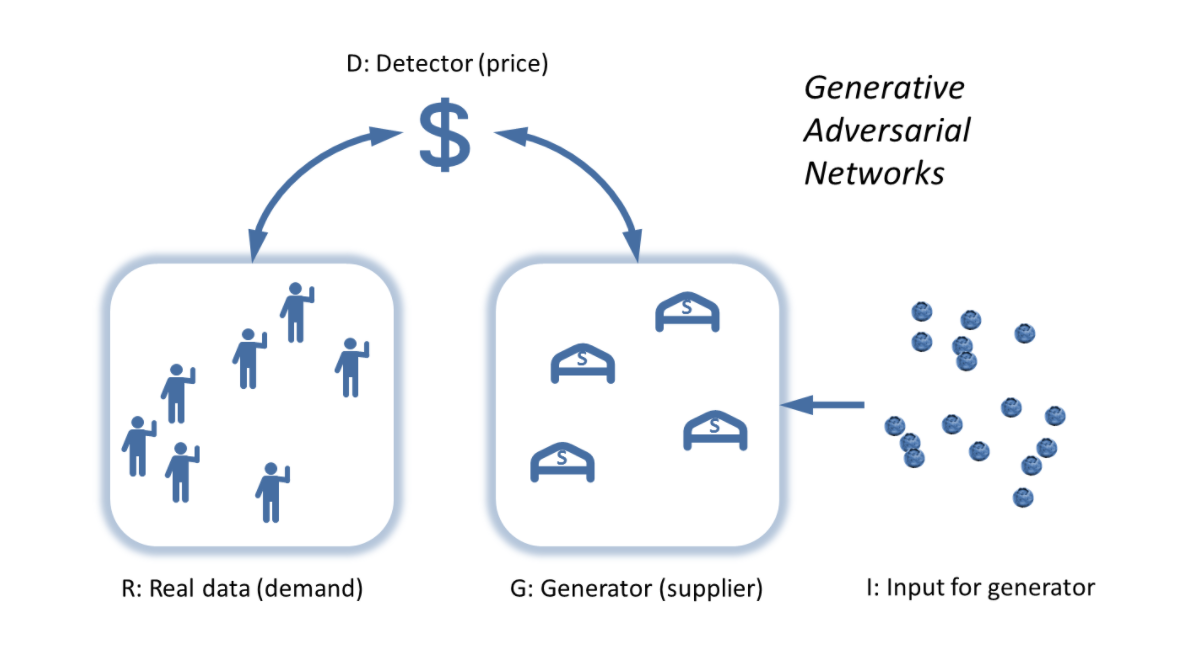

The picture above is of a functioning market as an algorithm matching distributions by raising and lowering a price until it reaches a stable price. In fact, this picture is of a specific machine learning algorithm called Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN, described in this Medium article or in the original paper) that has emerged recently. Of course, the idea of the market as an algorithm to solve a problem is not new. For example one of the best blog posts of all time (in my opinion) talks about linear programming as an algorithm, giving an argument for why planned economies will likely fail, but the same argument implies we cannot check the optimality of the market allocation of resources, therefore claims of markets as optimal are entirely faith-based. The Medium article uses a good analogy using a painting, a forger, and a detective, but I will recast it in terms of the information theory description.

Instead of the complex multidimensional distributions, here we have blueberry buyers and blueberry sellers. The “supply” (B from above) is the generator G, the demand A is the “real data” R (the information the deep learning algorithm is trying to learn). Instead of the random initial input I — coin tosses or dice throws — we have the complex, irrational, entrepreneurial, animal spirits of people. We also have the random effects of weather on blueberry production. The detector D (which is coincidentally the terminology Fieltiz and Borchardt used) is the price p. When the detector can’t tell the difference between the distribution of demand for blueberries and the distribution of the supply of blueberries (i.e. when the price reaches a relatively stable value because the distributions are the same), we’ve reached our solution (a market equilibrium).

Note that the problem the GAN algorithm tackles can be represented by the two-player minimax game from game theory. The thing is that with the wrong settings, algorithms fail and you get garbage. I know this from experience in my regular job researching machine learning, sparse reconstruction, and signal processing algorithms. Therefore depending on the input data (especially data resulting from human behavior), we shouldn’t expect to get good results all of the time. These failures are exactly the failure of information to flow from the real data to the generator through the detector – the failure of information from the demand to reach the supply via the price mechanism.

When asked by Quora what the recent and upcoming breakthroughs in deep learning are, Yann LeCun, director of AI research at Facebook and a professor at NYU, said:

The most important one, in my opinion, is adversarial training (also called GAN for Generative Adversarial Networks). This is an idea that was originally proposed by Ian Goodfellow when he was a student with Yoshua Bengio at the University of Montreal (he since moved to Google Brain and recently to OpenAI).

This, and the variations that are now being proposed is the most interesting idea in the last 10 years in ML, in my opinion.

Research into these deep learning algorithms and information theory may provide insight into economic systems.

An Interpretation of Economics for the Left

So again, Hayek had a fine intuition: prices and information have some relationship. But he didn’t have the conceptual or mathematical tools of information theory to understand the mechanisms of that relationship — tools that emerged with Shannon’s key paper in 1948, and that continue to be elaborated to this day to produce algorithms like generative adversarial networks.

The understanding of prices and supply and demand provided by information theory and machine learning algorithms is better equipped to explain markets than arguments reducing complex distributions of possibilities to a single dimension, and hence, necessarily, requiring assumptions like rational agents and perfect foresight. Ideas that were posited as articles of faith or created through incomplete arguments by Hayek are not even close to the whole story, and leave you with no knowledge of the ways the price mechanism, marginalism, or supply and demand can go wrong. Those arguments assume and (hence) conclude market optimality. Leaving out the failure modes effectively declares many social concerns of the left moot by fiat. The potential and actual failures of markets are a major concern of the left, and are frequently part of discussions of inequality and social justice.

The left doesn’t need to follow Chris Hayes’ advice and engage with Hayek, Friedman, and neoclassical economics. The left instead needs to engage with a real world vision of economics that recognizes the limited scope of ideal markets and begins with imperfection as the more useful default scenario. Understanding economics in terms of information flow is one way of doing that.

Is this just my lack of formal education or is this article very complicated? Honestly I did not understand it at all. Is there any way to explain this different? ( a link to a different way of describing informationtheory / free market theory)

Thanks Julia

To put it in more layman-friendly terms: price settings are based on information the suppliers gather regarding the market, both demand side and supply side (sales forecasts, commodity pricing, consumer confidence number, focus group information, etc). Demanders do the same. However, they can never have absolute, complete information for either side. So prices, and idea of what prices should be, in a free market never represent a true optimal price, but rather a best guess.

This pokes a few holes in neoclassical economic assumptions:

– Most obviously, prices cannot be optimal in a free market.

– Supply and demand changes cannot account entirely for changes in price, as refinements to the information flow can affect them as well.

– Information asymmetry corrupts prices, and can be used to exploit consumers.

– Information is dependent on a large enough sample size, so neoclassical economics is useless in markets with limited transactions. An easy example of this are those kind of items on shows like Antique Roadshow, where there’s so few of the items out there that the expert says, “This is a guess, but really it could go for almost any amount at auction.”

So the Left can use this to argue for non-market price controls (to account for the lack of free market price optimization) and for forcing corporations to have better fiscal transparency and more strict anti-trust laws (to increase information flow and to prevent information asymmetry).

Local prices for gasoline look a lot more like looting and chaos to me than any kind of correspondence to “markets.” Yesterday at the RaceTrac at the end of my street, “regular” dropped four cents from morning to evening, reflecting the pricing at the two other “service stations” at the intersection. A month or so ago (I got tired of keeping a little record of the changes) the price jumped 25 cents overnight. None of these moves seemed to correspond with the stuff I was reading about in the market conditions around the planet and just in the US — supply and demand? More like the Useless Looters at BP and Shell and others just spin an arrow on a kid’s game board to pick the day’s price point (that sick phrase), or somebody in the C-Suite decided the “Bottom Line” needed a goose to pump the bonus generator up a bit.

The fraud is everywhere, the looting and scamming too. Seems to me that searching for some “touchstone” to make sense of It All is an exercise in futility.

Gasoline runs into a different limitation with free market economics, which is that consumers need to be able to freely enter and leave the market in question in order for the free market to function (which is why privatized healthcare doesn’t work). Outside of a few urban areas with robust public transportation, most Americans are immediately dependent on gasoline in order to survive. Even those who do have access to a Metro are still dependent on the shipping that uses gasoline. So they can raise prices with a greater confidence that the number of consumers will not drop off as significantly as with other industries.

“This pokes a few holes in neoclassical economic assumptions:”

In neoclassical economics, these “holes” are pretty much understood as the prerequisites for “perfect competition”, as opposed to imperfect competition or monopolies.

When politics is mixed with economics, these are ignored, as they are in the interest of the ruling class.

Thank you for the laymans version PKMKII. I read it twice, but it only clicked after reading your comment.

https://aeon.co/essays/how-the-cold-war-led-the-cia-to-promote-human-capital-theory/

Good explanation for the layman or the lazy among us. Thank you.

In my truly layman line of thinking, I’ve always felt that the existence of “$X.99” was proof enough that there’s clear artificiality to pricing. Clearly, the lopping off of one cent is designed to make the consumer think of the lower number, and people regularly go right along with it.

e.g.

Joe: “How much does [thing] cost?”

Jill: “$29.” (That is, $29.99, and “$30” would be the more appropriate rounded answer, result after tax notwithstanding.)

PKMKII said it very well, and here’s another way to look at it: Centrally-planned economies (say, some Politburo minister in the former Soviet Union) fail because a central bureaucrat cannot possibly guess the demand and distribution for all products (say, metal bathtubs) across an economy in a given year. He guesses, poorly, and either the shortages or the oversupply make our history books.

Market economics makes a better guess, because pricing gives a dynamic estimate of what the supply and demand really are. That this estimate is generally *better* has been (mis)represented as that this estimate is somehow PERFECT — the best estimate that can possibly exist! As the article describes, this assessment (that only a market economy can generate maximal wealth and optimal wealth distributions) is FALSE.

The economics underlying communist central planning failed because they couldn’t provide the optimization that comes from valid pricing function. With Shannon’s information theory and advanced analytics, it is possible to create a more optimal economy than our current, simplistic market/pricing function provides.

Ever since Samuelson’s Economics in 1948, we’ve worshipped a market god based on scanty math. The first step in moving beyond Samuelson is recognizing that progress is indeed still possible, and then making the choice and determining the steps to pursue it.

Not just communist central planning. John Kenneth Galbraith’s The New Industrial State makes a special space in society for industries in The Planning Sector. These were the very large businesses that worked with huge capital bases, long lead times, populations comparable to small nations. Planning, both input and output, was key to these businesses because there was too much at stake to risk losing it to the whims of any market. Communist societies were extreme examples, as they were betting the entire national economy, but the parallels with huge “private” firms were quite exact.

The Planning Sector businesses failed when they had to slough off all the activities that were too hard to plan; then they morphed into the Finance/Insurance/Real Estate Sector.

“The economics underlying communist central planning failed because they couldn’t provide the optimization that comes from valid pricing function.”

Can any pricing function be valid if so much relevant information is missing in prices? There are lots of impacts outside the pricing mechanism and those impacts are not only massive, they are growing. The market does not allocate resources efficiently, it overuses the environment as a sink for waste, doesn’t really take into account temporal considerations, like the costs our current activities that will be passed off onto those in the future, the under-supply of public goods and the overuse of common pool resources, etc. Read into the socialist calculation debate, in particular the ideas of Otto Neurath. Highly relevant when it comes to the monetization of environmental externalities. Von Mises himself admitted that there were limits to monetization and said that to the extent that the market ignored impacts, it would be “irrational”. Well, it does, it is irrational, and it is long past time that we acknowledge the limits to markets and value scientific information just as much, in some cases more, than things that have market values. I don’t understand how people can look at the environmental crisis and not see the role of markets in getting us here.

Oh, and regarding central planning, Oskar Lange (who was also part of the socialist calculation debate) pointed out that computers would allow people in the future (now) to do things that were very hard then. He was right, not that I want a Stalinist economic system. Beyond that, since markets are dominated by a handful of powerful companies and since financial decisions in this financialized economy are in the hands of giant financial institutions, do we not have central planning? I mean, weren’t there financial interests powerful enough to rig the LIBOR, doesn’t the BIS have lots of power, doesn’t private financial capital create most of our money within the “fractional reserve banking system, doesn’t the WTO and trade tribunals within trade deals have the capacity to undermine laws, even at the local level?” How is that not central planning? Seems that it is also just as unaccountable to the public as the old Soviet system was.

I don’t think it is a lack of formal education. It is simply written in a way that is not easy to understand. I have my master’s in engineering, and I’m still not sure exactly what this passage is trying to say:

“If you randomly generated thousands of messages from the distribution of possible messages, the distribution of generated messages would be an approximation to the actual distribution of messages. If you sent these messages over your noisy communication channel that met the requirement for faithful transmission, it would reproduce an informationally equivalent distribution of messages on the other end.”

From that point on I simply skimmed it and, if I’m not mistaken, the author also assigns positions to Hayek that seem to be a little more extreme than the positions he actually held.

Will try to break that:

You can only get to the true distribution assuming an infinite number of samples, everything else is asymptotic approximation to the true posterior distribution. This is true for any mathematical function approximated numerically were closed solutions are not possible to find (ie. not integrable). But this is relevant to the second phrase because:

A noisy communication channel introduces random bits of information which are not part of the original distribution, but because that noise is random, you would get a message that is an approximation of the true distribution of the original message being transmitted (is informationally equivalent) as the noise is distributed ‘randomly’ .

However, this is only true when the number of information bits approach infinity (for large numbers), BE WARE! Indeed that randomness can be very skewed for small samples. this is relevant and interesting because complex systems were you have a large number of variables are not easy to converge with, even when you are aware of the whole system variables (is a mathematically intractable problem).

You can think as market pricing (in an ideal world free of politics and power games, which is not) as a convergence to a complex multidimensional problem, and even though we know that we are NOT aware of all the variables at play for a given product, hence this supposedly God like attributes of market price discovery are unwarranted.

Looking at the signal gives you both information and a probability of being correct. Now we get to significance, which is defined as 95% probability.

When you get to 95% probability depends on the signal to noise ratio.

Any guesses as to the signal to noise ratio of the News Media?

Actually that’s just poor writing.

No Julia, this is a “very complicated” subject matter. And always has been. One rule of thumb I have, just my take mind you,is….any time someone offers you ‘sweeping, definitive like, answers’ I cease paying attention. And further, any time someone offers an opinion that I should not read the thought leaders in ALL respective schools of economics, i reject almost all advice from that person. In case you are looking for a readable book on this subject matter (still a hard read, mind you), here is one example:

https://www.amazon.com/Never-Serious-Crisis-Waste-Neoliberalism/dp/1781680795

“Because the information flow from A can never be greater than A’s total information, and will mostly be less than that total, the observed prices in a real economy will most likely fall below the ideal market prices.”

Surely not. Post-industrial economies feature an asymmetry: individual consumers, catered to predominantly by large nationwide publicly-traded suppliers.

Because of the superior knowledge possessed by suppliers, further leveraged by advertising and publicity which exploits human psychological foibles such as peer pressure and herding, prices in the economy are almost certainly too high versus the ideal of complete information flow (while the price of labor is almost certainly too low).

Nowhere are prices higher than in the nonnegotiable, monopoly services of government. Not only does it charge astronomical property taxes which mean that there’s really no such thing as secure property title without income, but also it compels hapless working schmoes to “invest” 15.3% of their income for their entire working lives at approximately zero return.

Mr Trump … tear down these prices.

Really? Care to discuss an example?

Such as the UK NHS v the US Health Care System? Better outcome at nearly half the cost.

Now how is your ” prices higher…monopoly services of government” doing?

Please post a counter example.

With respect, it is not empirically incorrect that immigration lowers wages. The historical experience is quite clear, that when governments force population growth, whether through increased immigration or via incentives to increase the local fertility rate, wages for the many fall and profits for the few increase.

Sure more workers means more competition for jobs, but can also result in an increase in the number of jobs – BUT ONLY OVER TIME AND ONLY IF NEEDED INVESTMENTS ARE MADE AND THERE IS ENOUGH MARGINAL CAPACITY TO INVEST AND TECHNOLOGY AND RESOURCES ARE NOT ENTERING THE AREA OF DIMINISHING RETURNS. Which is not guaranteed, especially if the immigration level is massive and constantly increasing.

The United States from around 1929 to 1970 had very low immigration, and, starting from a low level, wages soared. Starting in 1970, the borders to the overpopulated third world have been progressively opened, and wages have started to diverge from productivity and are now starting to decline in absolute terms. Other nations that recently increased the rate of immigration and have seen significant falls in wages are: South Africa, the Ivory Coast, England, Australia, and Singapore – and even some provinces of India, where immigration from Bangladesh has been used to make certain that wages stay near subsistence. Yes immigration was not the only thing going on there, but when rapid forced increases in the supply of labor are always followed by falls in wages, well, the empirical evidence is hardly to be dismissed out of hand.

Remember, no society in all of history has run out of workers. When the headlines say that immigrants are needed to end a labor ‘shortage’ what is really meant is a ‘shortage’ of workers who have no option but to accept low wages. However, the only reason that workers can get high wages is that there is a ‘shortage’ of workers forced to take low wages. It is thus essentially tautological that when immigration is said to eliminate a labor shortage, it is lowering wages, because a labor ‘shortage’ is in fact what high wages are based on.

They’re arguing that you can’t empirically say that immigration decreases wages, because there are simply too many variables in an economy to be able to say definitively if it’s a cause or a correlation, i.e. does the immigration decrease wages, or does another socio-economic factor simultaneously decrease wages and cause an influx of immigrants? This is why economics is treated as a soft science, as you can’t remove variables in a lab setting the way you can with other sciences.

“BUT ONLY OVER TIME AND ONLY IF NEEDED INVESTMENTS ARE MADE AND THERE IS ENOUGH MARGINAL CAPACITY TO INVEST AND TECHNOLOGY AND RESOURCES ARE NOT ENTERING THE AREA OF DIMINISHING RETURNS.”

Nope. Once immigrants arrive, demand increases instantly, even before they get a job.

(Jason) Smith says that immigrant labor just pops out goods and services all by itself, but if that was true, why didn’t they do it back home? Labor actually makes goods and services by combining with land, capital, and resources, and the immigrant doesn’t bring those things with him, only his labor.

He’s coming for the land, capital, and resources, and he must either be content with the fraction of those things that was hitherto left untouched because they were the least desirable (and hence push outward the extensive margin of cultivation), lowering wages and increasing rents, or he must appropriate the fraction that hitherto were available to native workers (and hence force them out beyond the previous margin of cultivation).

It’s all in Ricardo, what do they teach them in these schools?

(never mind Ricardo, it’s in Marx! Why do pro-immigration boosters never understand the importance of “means of production”?)

Wow. Just wow. A complete, through, and total BS assertion of some kind of economic theory. I am simply stunned at his verbal density of discourse, blithe refusal to explain, and simply name dropping facts, ideas, and concepts that are absolutely not related except in being part of the English language.

I know this is close to an ad hominum attack; I haven’t given any specific rebuttal. But I don’t have the tools at my disposal right now to avenge what I see as an assault on my analytic abilities.

Good night and good luck.

Perhaps you should do some reading or studying of math?

If not a specific rebuttal, what *kinds* of things in the article do you disagree with? Perhaps this posting is just a step to some greater knowing. Neoclassical Economics has been taught as “factual and beyond dispute” my whole career — I’m sure that Alchemy and Leechbooks were taught similarly in earlier ages. How might you suggest that we move forward to something better?

This reply is late for reasons too many to say, but for the record, I disagree with Smith’s premise that Information Theory has anything to tell about Economics. Smith’s & Hayek’s start with that ‘price’ is information (Ok, I agree conditionally) and that the market is really an exchange of information (I strongly disagree here) and therefore Information Theory has insights in how markets and economies work (haha, here I would just laugh them out of the room) because Information Theory, as discussed in Shannon’s paper, is about how much info can be shoved down a communication channel, not about the message itself. And not about how ‘information’ is generated, understood, and used by people.

“Wow. Just wow. A complete, through, and total BS assertion of some kind of economic theory. I am simply stunned at his verbal density of discourse, blithe refusal to explain, and simply name dropping facts, ideas, and concepts that are absolutely not related except in being part of the English language.”

Yeah… that is a pretty good summation of my experience wrt Austrians over almost 2 decades in a nutter shell[…] kudos.

Now if only the neoclassicals would abandon the individual and consider vectors in distribution and how groups affect information.

disheveled….. throws toys out of play pen and hurrumphs away…. victoriously….

In my limited experience the prices we accept are more to do with contentment than information. We are aware that we can never have perfect information; bounded rationality being our situation*. So as buyers, we end up going with contentment or at least convenience; price too high, content to leave it on the shelf. Price too low and the reaction might be the same because it is too good to be true, or of suspect quality. You can have a bargain staring you in the face and, but you are content because of lack of interest or knowledge.

Good luck to those who try to quantify contentment!

….And then there is the tyranny of choice; not content!

Pip Pip!

* When it comes to the prices people are prepared to pay for products such as cosmetics and super-cars the rule seems to be unbounded irrationality, but hopefully contentment is achieved anyway.

Please do not confuse commodity price with perceived value.

Perceived value is clearly a signal injection into the information stream (an engineers view of marketing)

when it comes to the political application of this ‘theoretical’ argument I think it will be easily dismissed as more leftist academic pedantry, ‘immanentizing the eschaton’- all the comments reflecting the advantages of imperfect information evidence.

This is a wonderful, cogent explanation of a very mathematically complex subject, which is Information Theory, that has been used to make profound contributions well beyond telephonic communication for which Claude Shannon developed it, when he discovered it trying to code the English language, and which he failed to do.

R.A. Fisher was also brilliant. His work has had implications in probability, and statistics, economics, and perhaps most profoundly in genetics.

The neoclassical analysis also doesn’t account for single supplier, multiple demand market situations. If blueberries both have the consumer market, but also an industrial market (dye purpose, maybe), then the blueberry supplier has to balance both of those demands, which may end up favoring one or the other, or some state that isn’t ideal for either demand market. The universal example is the private property of the business itself. The owner isn’t just in the market of whatever service or widget they make, but also in the commercial real estate market. This is especially problematic with housing, as high rents + vacancies create the impression of scarcity and value to prospective buyers.

Good work. Now add the delays in information transfer, and fear and greed buying motivations based on multiple information streams, coupled with information conflicts (injected noise), and you are getting closer to the real world.

Information conflicts are the differing explanations of the Trump/Corey affair. There is much noise in the information stream.

The example seems very sketchy:

This is a good example because it’s easy to understand appealing, I fear, to our neoclassical prejudices.

It’s a bad example because it doesn’t seem very multidimensional; appealing to our neoclassical prejudices it collapses easily into “How many blueberry buyers?” and “How many blueberries?”

Trying to imagine something more multidimensional … there might be a preference for big blueberries because they’re big … there might be a preference for small blueberries because people think that they’re wild, so they must be tastier. If the markets were segregated, there could be a market-clearing price for big blueberries, and another for small blueberries. But the markets probably aren’t segregated, and the prices would play back and forth against each other.

Maybe good too in dealing with prices of different goods, not just The Price. Neoclassical prices are meant to be the information that tells me whether to buy dish soap or a new overcoat instead.

There are no stable prices. With this analysis, the steps to include feedback is clear, and if the feedback is non-linear, non-linear feedback is a characteristic of chaotic systems.

Temporary stability only in a non-linear system, with tipping points etc.

Thank you for this, I found it very helpful.

Chris Hayes is an idiot. What kind of person can repeatedly visit the post-industrial wasteland of the rust belt for town halls with Bernie Sanders and then say “what we need more of is the philosophy of free-markets”?

But even with that being said, Hayes somehow is still by far the most worthwhile personality on MSNBC.

I think the tradition of economic thinking has been really influential. I think it’s actually a thing that people on the left really should do — take the time to understand all of that. There is a tremendous amount of incredible insight into some of the things we’re talking about, like non-zero-sum settings, and the way in which human exchange can be generative in this sort of amazing way. Understanding how capitalism works has been really, really important for me, and has been something that I feel like I’m a better thinker and an analyst because of the time and reading I put into a lot of conservative authors on that topic.

While I agree with much of the argument Hayes is making – know thy enemy, etc. – he gets one huge thing wrong here that is very troubling: equating capitalism with markets. “Understanding how capitalism works has been really, really important for me …” I’m amazed at how often this trips up otherwise smart people. There is no capitalism in mainstream neoclassical economics (no government either, and you can’t have capitalism without government). And get any business person talking freely and they will tell you that everyone in business hates super-competitive markets of the kind fetishized by economists, and that profitability is all about finding niches and other ways to avoid competition.

I also don’t for the life of me understand how anyone can argue that neoclassical economics has anything to do with actual reality. There are massive problems as far as the assumptions of their models, how they model at the micro-level and then aggregate to the macro by assuming everyone is a clone, how they assume things in regards to information, competition, and foresight, their reliance on individual utility maximization, how their models struggle to explain consumption of anything more than a few goods under very restrictive assumptions, their reliance on equilibrium (and the insane assumptions needed for general equilibrium), as well as the huge problems with neoclassical capital theory. Steve Keen also has pointed out that many of their models don’t include money and assume barter, and they were incapable of creating conditions that resulted in a financial crisis. There’s lots of other examples too.

https://aeon.co/essays/how-the-cold-war-led-the-cia-to-promote-human-capital-theory

“Friedman had discovered in human capital theory more than just a means for boosting economic growth. The very way it conceptualised human beings was an ideological weapon too…”

I think it’s important to recognize where information theory and the principle of maximum entropy does succeed in economics and that is as a method of doing statistical inference in economics. For those interested, I would recommend looking at the increasing amount of information theoretic research coming out of the Economics Department at the New School for Social Research and UMKC. You can find many good working papers by myself, Duncan Foley, Paulo dos Santos, Gregor Semieniuk, and others on the NSSR Repec page https://ideas.repec.org/s/new/wpaper.html.

I really really do not like Hayek and neoliberalism and was very disappointed this post didn’t give the guy a good knee-capping as promised. … So … feeling ornery I went to the site you referenced and took a quick look. Wouldn’t the math skills reflected there be more fruitfully applied through a return to physics and/or chemistry? I was never happy with the explanation given for just what entropy measured. How about coming up with an ab initio definition for entropy? I suspect information theory might come into play in such an effort. The existing definition for entropy seems like the definition for a remainder term capturing all the conserved stuff in a thermodynamics problem that doesn’t quite fit into the heat or mechanical work boxes.

I scanned one paper at the site. All the fancy mathematics used to derive a distribution of profit rates and their evolution over the years using Smith’s classical theory of competition misses a lot of the details of what happened in the U.S. economy for firms during the years 1962 – 2012. Where do the distributions capture the massive consolidation of the U.S. economy and its impacts on profits. And what about interest rates, shifts in investment strategy and the impacts of financialization and financial predations on firm behaviors? How do massive stock buybacks, Xtreme executive pay and outsourcing and shifting profits to overseas books tie in with an idea of firms acting based on minimum informational entropy? The actions of some firms like General Motors suggest their management had trouble understanding the difference between maximizing profits and maximizing their rate of return and they demonstrated complete ignorance of Kenichi Ohmae’s ideas on business strategy [I drive a Honda]. How does GE’s Neutron Jack and his arbitrary 15% rule which set a fashion style for managerial macho during those years fit with informational entropy? Why waste strong math skills on a dying school of neoclassical economics?

Hi, Jeremy,

I think you share a very common concern when it comes to the application of information theory and statistical mechanics to economics, be it neoclassical or classical political economy. I think a lot of the confusion around these issues stem from the frequentist theory of probability and attempts to directly apply statistical mechanics as a physical theory to economic systems. The information theoretic approach defines entropy simply as a measure of uncertainty and the principle of maximum entropy as a method for maximizing our uncertainty given any relevant information about the system being studied. The roots of this approach are in the Laplacian and Bayesian tradition of statistical inference and are well articulated by Edwin T. Jaynes.

In economics we deal with problems of aggregation in complex capitalist systems with many degrees of freedom. The complexity of an economic system requires some method of abstraction. The neoclassical tradition conceptualizes equilibrium as fixed point equilibrium and relegates any residual fluctuations to the status of “random noise.” When it comes to predicting actual economic data, neoclassicals could never predict the type of statistical regularities we see e.g. in the the profit rate data. The best they can do to combat the data is introduce epicyclic variations on imperfect competition. Not very satisfying.

If one is interested in studying and explaining the spontaneous organization and statistical regularities we actually see we must explain the residual indeterminacy (endogenous fluctuations) of the system. Contrary to neoclassical thinking this requires we actually develop an explanation for the feedbacks and cumulative causation inherent in the system. The enormous success in physics in dealing with similar problems of large hypothesis and state spaces is the notion of ensemble reasoning, which ignores detailed microeconomic explanations, such as methodological individualism, in favor of systemic properties, such as competitive pressures. What’s so interesting about looking at the distribution of the profit rate is that the historical details of what happened in the U.S. economy appear to be irrelevant to the formation of the profit rate distribution. They may help to explain the evolution of the parameters of that distribution, but the fact that year after year we see such remarkable organization of profit rates strongly suggests there are consistent regulating forces. Instead of ignoring deviations from the average rate of profit as random noise, the goal is to understand what those regulating forces are that give rise to what we refer to as a “statistical equilibrium.” Information theory forces one to make their assumptions (knowledge of the system) explicit. If we assume that all firms have the same rate of profit and we maximize entropy subject to that constraint, we’ll predict a degenerate distribution of profit rates, which is clearly a terrible theory when it come to being supported by the data.

At Bell Labs, plaques and a statue of Shannon occupy places of honor, in more prominent places than the tributes to other prominent people (including 8 Nobel Prize winners in science).

Here’s a presentation by Prof. Christopher Sims of Princeton, at Bell Labs. “Information Theory in Economics” https://youtu.be/a8jt_TmwQ-U – critique of the optimizing rational behavior models, noting people are bandwidth limited (“Rational Inattention”). Non-gaussian! Brings up example of monopolist of with no high capacity limit vs. customers.

Phillip Mirowski challenged the left to directly attack and defeat the neoliberal belief that markets are information processors that can know more than any person could ever know and solve problems no computer could ever solve. [Prof. Philip Mirowski keynote for ‘Life and Debt’ conference https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7ewn29w-9I ]

Sorry for the long quote — I am loathe to attempt to paraphrase Hayek

————————–

“This is particularly true of our theories accounting for the determination of the systems of relative prices and wages that will form themselves on a wellfunctioning market. Into the determination of these prices and wages there will enter the effects of particular information possessed by every one of the participants in the market process – a sum of facts which in their totality cannot be known to the scientific observer, or to any other single brain. It is indeed the source of the superiority of the market order, and the reason why, when it is not suppressed by the powers of government, it regularly displaces other types of order, that in the resulting allocation of resources more of the knowledge of particular facts will be utilized which exists only dispersed among uncounted persons, than any one person can possess. But because we, the observing scientists, can thus never know all the determinants of such an order, and in consequence also cannot know at which particular structure of prices and wages demand would everywhere equal supply, we also cannot measure the deviations from that order; nor can we statistically test our theory that it is the deviations from that “equilibrium” system of prices and wages which make it impossible to sell some of the products and services at the prices at which they are offered.”

[Extract from Hayek’s Nobel Lecture]

—————————

This just hints at Hayek’s market supercomputer idea — I still haven’t found a particular writing which exposits the idea — so this will have to do.

Sorry — another quote from the Hayek Nobel Lecture [I have no idea how to paraphrase stuff like this!]:

—————————-

“There may be few instances in which the superstition that only measurable magnitudes can be important has done positive harm in the economic field: but the present inflation and employment problems are a very serious one. Its effect has been that what is probably the true cause of extensive unemployment has been disregarded by the scientistically minded majority of economists, because its operation could not be confirmed by directly observable relations between measurable magnitudes, and that an almost exclusive concentration on quantitatively measurable surface phenomena has produced a policy which has made matters worse.”

—————————-

I can’t follow Hayek and I can’t follow Jason Smith. The first quote above sounds like a “faith based” theory of economics as difficult to characterize as it is to refute. The second quote throws out Jason Smith’s argument with a combination of faith based economics and a rejection of the basis for Smith’s argument — as “scientistically minded.”

I prefer the much simplier answer implicit in Veblen and plain in “Industrial Prices and their Relative Inflexibility.” US Senate Document no. 13, 74th Congress, 1st Session, Government Printing Office, Washington DC. Means, G. C. 1935 — Market? What Market? Can you point to one? [refer to William Waller: Thorstein Veblen, Business Enterprise, and the Financial Crisis (July 06, 2012)

[https://archive.org/details/WilliamWallerThorsteinVeblenBusinessEnterpriseAndTheFinancialCrisis]

It might be interesting if Jason Smith’s information theory approach to the market creature could prove how the assumed properties of that mythical creature could be used to derive a proof that the mythical Market creature cannot act as an information processor as Mirowski asserts that Hayek asserts. So far as I can tell from my very little exposure to Hayek’s market creature it is far too fantastical to characterize with axioms or properties amenable to making reasoned arguments or proofs as Jason Smith attempts. Worse — though I admit being totally confused by his arguments — Smith’s arguments seem to slice at a strawman creature that bears little likeness to Hayek’s market creature.

The conclusion of this post adds a scary thought: “The understanding of prices and supply and demand provided by information theory and machine learning algorithms is better equipped to explain markets than arguments reducing complex distributions of possibilities to a single dimension, and hence, necessarily, requiring assumptions like rational agents and perfect foresight.” It almost sounds as if Jason Smith intends to build a better Market as information processor — maybe tweak the axioms a little and bring in Shannon. Jason Smith is not our St. George.

But making the observation that there are no markets as defined makes little dint on a faith-based theory like neoliberalism, especially a theory whose Church encompasses most university economics departments, most “working” economists, numerous well-funded think tanks, and owns much/most of our political elite … and so effectively promotes the short-term interests of our Power Elite.

This is effectively my stance as well, albeit understand the need for a broad and comprehensive dialog – contrary to the last decades.

Posts such as this show even in the dominate economic discipline that previous concepts were rudimentary, given unwarranted gravitas [econnomic law], then extenuated beyond without sound methodology to substantiate it [goal seeking].

disheveled…. the dominance part is the cornerstone that is intransigent as it has time and space locked up past, present, and near future.

@Jeremy Grimm

Thanks for the reference to Mirowski. I find his work fascinating, and his discussion of von Hayek particularly interesting.

I wonder especially at the quote you provided, “we, the observing scientists, can thus never know all the determinants of such an order, and in consequence also cannot know at which particular structure of prices and wages demand would everywhere equal supply, we also cannot measure the deviations from that order; nor can we statistically test our theory that it is the deviations from that “equilibrium” system of prices and wages which make it impossible to sell some of the products and services at the prices at which they are offered.”

Does this mean that von Hayek has given up on empirical science? When he says “we also cannot measure the deviations from that order” this sounds like he is “admitting,” so to speak, that he doesn’t have a testable theory. In other words, he is “not even wrong,” as Wolfgang Pauli supposedly said.

When John Cassidy interviewed Eugene Fama, Fama makes an almost identical remark:

http://www.newyorker.com/news/john-cassidy/interview-with-eugene-fama

I find this flabbergasting. It appears to me that Fama, and perhaps von Hayek claim that they are right by definition! If it is truly going to be impossible to tell if your theory is correct, then you should immediately give up and start working on something meaningful.

I honestly don’t understand. Should Fama be taken seriously when he says this? Can you interpret von Hayek in this way?

With respect to Smith’s interesting look at information theory . . . it is unclear to me what good it does to argue with people who don’t feel there is empirical evidence relevant to their “theories.” I don’t think von Hayek’s fundamental or even peripheral problem is that “he didn’t have the conceptual or mathematical tools of information theory to understand the mechanisms” operating between information and price. My cynical view is that his problem was that he didn’t formulate a hypothesis that was clear enough to be tested and examined in a meaningful way.

Best,

Peter

Smith’s article reminds me of some comments of Bruce Wilder, which are roughly along these lines:

The implicit neoliberal claim that markets exist is objectively false in many (most?) cases.

Markets – actual markets – are rare

We could stop lying about the price mechanism and recognize we live in a command-and-control economy, controlled by rules not prices, by bureaucracy not markets

Hierarchy is the central aspect of the economy, not markets

Supply curves imply rising marginal costs – we usually have falling marginal costs

Interesting, but I thought this would be a post about game theory – esp. games of incomplete and/or imperfect information (e.g., Akerlof, Stlten). There’s no theory of agent loss or information asymmetry and hence no discussion of fraud in neoclassical models. Even Coase has something to say about institutions reducing the complexity of contracting way back in Hayek’s day (viz. transaction costs).

Neoclassical economists have no theory of property, no theory of money – really no theory of why anything is valuable at all and how it might be appropriated or misappropriated. They don’t have a theory of property rights, how they are defined or enforced or any theory of government function (or its corruption). It’s what they make invisible that gives them such power. They don’t understand the simple legal processes of business because the law should never be just another market-clearing auction, so they inevitably lose interest.

As far as economies being complex systems, you should check out the work on dissipative systems and entropy, which has advanced quite considerably in recent years. Even in the ’90s the field was far ahead of where economics is mired today.

The compression of “a complex multidimensional space of possibilities that includes the state of the world and the states of mind of thousands or millions of agents” does routinely occur. You’re talking about a strange attractor in nonlinear/chaos math. Although a single dimension is unlikely to underly so many variables, the actual dimensionality might be quite low – which could afford the possibility of predictions (with enough observations). You can tease out its dimensionality with a simple spatial correlation test. I wrote code to do exactly this in the early ’90s.

There are more complex tests for nonlinear moments in frequency analysis, if you like. Mel Hinich and others routinely did these kinds of analyses on stock returns way back in the ’90s and found regular patterns with higher order nonlinear moments. Mandelbrot did fractal dimensionality calculations on trading series even earlier.

Decomposition of complex voting behavior into lower dimensions is even possible (e.g., ideological scaling). The subdiscipline of political science is called spatial theory and is about forty years old now (founded by Mel Hinich and James Enelow, my old grad school professors).

So these complex systems do routinely decompose into lower dimension systems. Compression is possible when entropy is less than degrees of freedom/dimensionality. It’s why you can compress text and why some people routinely beat the markets.

P.P.S. The ideoogical scaling of spatial theory shows you how voters themselves can process information on a plethora of candidates in a limited number of dimensions quite accurately.

Munch! :)

It is nice theory but in fact makes so many unrealistic assumptions or uses many neoclassical and other dogmas while ignores Marx extensive work on the markets in his Capital.

I see no Marxian input in this model.

1.Marx rejected notion of any monetary theory or policy so talking about price is already to succumb to a dogma. Marx instead talked about absolute value, use value or exchange values, commodities values expressed in other commodity values, no money involved. In fact he saw markets that use money as markets not for commodities or goods but for money itself, where sellers and buyers of money converge and determining its instant values in a form of price while values of commodities are mostly retained, barely changed.

2.Marx rejected notion of Supply and Demand as governing economic law and instead saw S-D balance if ever achieved as a result of market manipulation of balances of commodities access to the market or just access to information about them often aimed to achieve a certain price for certain market players.

3. In exchange markets fundamentals are always overshadowed by third party considerations (entirely outside of market) and most of all determined by a measure or guess or previous arrangement for potential profit.

Here I found an interesting theoretical view of real markets (no math):

https://contrarianopinion.wordpress.com/economy-update/