Our mini-fundraiser for Water Cooler is on! As of this writing, 208 donors – our goal is 250 – have already invested to support Water Cooler, which provides both economic and political coverage, to help us all keep our footing in today’s torrent of propaganda and sheer bullsh*t. Independent funding is key to having an independent editorial point of view. Please join us and participate via Lambert’s Water Cooler Tip Jar, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, or even the US mail. Thanks to all!

Yves here. Even though this post takes a UK perspective, the UK is a neoliberal fellow traveler, as well as a fast adopter of America’s dubious executive pay practices, so much of the overall profile is similar. One point of differentiation is that the US tax system is progressive but our government spending is regressive (as in the transfer payments to lower income groups pale compared to subsidies to capital-owners via our many forms of socialism for the rich).

The author sets forth a short, high level list of sound recommendations. But what will it take to get any of them implemented? The history of the protracted struggle in America for rights like workplace safety, reasonable hours and better pay, is almost entirely absent from histories, even economic histories. And that may be no accident due to the high cost in terms of protestor life and limb. Oppressed workers no longer seem willing to take that sort of risk, particularly since corporations seem to hold so much entrenched power. But how was that any different in the days of debtcroppers, robber barons, Pinkertons, and later, trusts?

By Desmond Cohen, previously an Economic Advisor to HM Treasury, and subsequently Reader in economics and Dean of the School of Social Sciences at University of Sussex. Originally published at Open Democracy

A great deal has been written in recent years on the topic of inequality. The books of Thomas Piketty and the late Tony Atkinson are just two recent examples. It is hard to believe that anyone can be unaware of the issues and the possible explanations of why there has been such a massive shift in income and wealth distribution in both rich and poor countries. And yet it is still possible to be surprised at what is going on at the highest echelons of business. Here is just one example, as reported in the Guardian earlier this month:

Burberry is to hand Christopher Bailey shares worth £10.5m next month when day-to-day management of the luxury goods retailer switches to a newly recruited chief executive. Bailey is to receive 600,000 of the 1m shares he was awarded in 2013, at a time when the company was concerned he might be poached by a rival. Bailey will receive the rest of the 1m shares at a later date and at the current share price of £17.65 the 600,000 that he will receive are worth about £10.5m.

The annual report published on Tuesday shows that Bailey was paid £3.5m last year – up from the £1.9m the previous year. While he waived his entitlement to any annual bonus for the year, his total was boosted by a £1.4m payout from a further award of shares in 2014. ….In 2014 the company had endured a bruising annual meeting with its shareholders, who voted against its remuneration report to protest about Bailey’s pay. His pay deals also include a £440,000 allowance to cover clothes and other items.

Bailey’s salary will remain at £1.1m when he becomes president next month, following a year in which underlying profits fell by 21%.

Burberry isn’t exactly at the forefront of technical innovation and nor is it a company supplying a product that most of us would consider essential to life and limb. It caters of course to the global rich and its success until recently in expanding sales has depended on precisely the shift in income and wealth that has been measured by Piketty and others. But relative to average wages in the same company and to median household income in the UK, the scale of the payments to Bailey seem unreasonable. This is someone who has presided over a 21% fall in profits, and yet is still rewarded by a huge set of payments. What does this say about corporate governance and any supposed relationship between payment and performance?

It is perhaps unsurprising that in the land of Thatcherism the UK comes out very unfavourably in international comparisons of income and wealth distribution. In the UK the top 10% of households have disposable income 9 times that of the bottom 10%. But the level of inequality is much higher for original pre-tax incomes where the top 10% is 24 times higher than the bottom 10%. It is even worse than this within the top 10% where the level of inequality is greater; the top 1% of households on average had an income of £253,927 and the top 0.1% had an average income of £919,882 in 2012. The UK is the 7th most unequal country in the OECD, and the 4th most unequal country in Europe.

In the case of wealth, inequality is even greater. The richest 10% of households hold 45% of all wealth and the poorest 50% have 8.7%. Within the OECD countries the UK has a gini coefficient for wealth inequality a little higher than the rest of the members [73.2 compared to 72.8].

In an interesting paper in 2012 the Bank of England argues that more or less every citizen gained to some degree from the fact that monetary expansion after the 2008 crisis generated additional demand and growth in GDP of 1.5 to 2.0%. Perhaps, but more importantly quantitative easing (QE) both directly and indirectly increases asset prices, and since ownership of financial assets is skewed most of the capital gain accrues to those with the largest holdings. Thus it is the top 5% of households in the UK hold 40% of financial assets who gained the most.

This is equivalent to the top 5% each receiving £128,000 as a result of QE in the years prior to 2012. Since QE has continued to be central to monetary policy in the UK since then, the richest have continued to be the main beneficiaries. It is reasonable to assume that in the 5 years since the Bank made its estimates that another £130,000 or so has been added to the wealth of each of the top 5%.

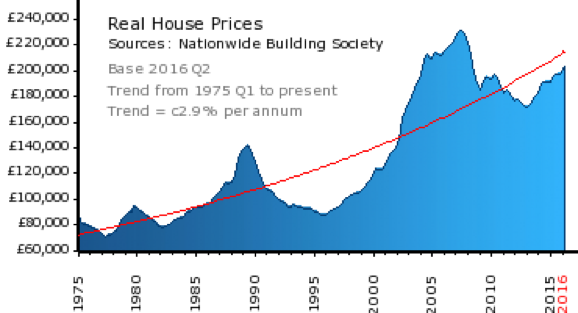

It is also worth noting that the UK has had massive property price inflation in part as a result of the liquidity generated by QE. Again, the greatest benefit will have accrued to the richest segment of the population. This gain is an additional transfer to the top 5% since real gains on property were excluded from the Bank’s estimates. The scale of the rise in house prices both has been enormous. Nominal house prices on average increased between 1975 to 2016 by more than 800%, while real house price growth (after inflation is considered) was 333%. The following chart from Nationwide the biggest UK lender for housing finance maps the trend over the whole period since 1975.

What we face in the UK and elsewhere in the EU is a situation of deep and growing income and wealth inequality which in part has its origins in globalised trade but also in trends in technological development that substituted precarious work for previously well paid and secure employment. But we also witness governments both in the UK and across the EU following tax policies that are increasingly regressive in their impact, with greater dependence on indirect taxes and reductions in the degree of tax progressivism in income taxes.

In practice corporate taxes are increasingly easily to avoid, which also raises the returns to owners of capital. Meanwhile, the power of labour organisations has weakened which has enabled capital to grab a larger share of net product and hence a higher share of national income and wealth. To these forces we have also identified the actions of central banks who through their activities have directly and indirectly caused further income and wealth inequality.

Present levels of inequality threaten social, economic and political stability. It is now generally agreed as to what to do, but the problem is that years of increasing inequality have embedded the interests of the rich and powerful such that governments more or less everywhere have been captured and are no longer representative of their populations. But the structural forces at work will make it difficult for governments to continue with present policies, and they will have little option but to change direction. Populism and the rise of extreme parties of the left and right will inevitably lead to change, but why wait for this to happen?

The broad outlines of policy reform are clear:

- Monetary policy needs to revert to its more traditional role with a much reduced level of dependence on QE. Savers need to be offered higher real rates of interest and credit needs to be brought under more effective control. Banks and other financial intermediaries need to be effectively regulated and their stability should be the focus of the monetary authorities. Where QE is continued it should be used to serve the interests of the country and not the rich few, and this would mean using monetary expansion for financing public investment in a sustainable way – both social and economic investment.

- Fiscal policy needs to be given a much greater weight and needs to become much more progressive in terms of tax structure. The current regressive nature of the tax system needs to be reversed with much greater reliance on income taxes and much less on indirect taxes. Corporate taxes need to be increased and loopholes closed so that the effective tax rate is moved closer to historical levels. In particular corporate taxes should be based on where revenue is received rather than on profits so as to make it much more difficult for companies to avoid taxation. Wealth taxes need to be made more effective and loopholes closed especially in relation to the passing of wealth between generations which is presently a major avenue for processes of inequality to persist and deepen over time.

- Political reform is essential so that the role of money and corporate power is removed from the political process. This has become even more critical now that it is evident that social media such as Facebook have been infiltrated by organisations that manipulate data and information in the interests of the rich and powerful. Political systems have become corrupted and urgently need reform.

- Wages are too low and this threatens economic stability. It is critical that real wages be increased in part through changes in wage policy in respect of public sector employees where there has been wage restraint, and in part through policies to strengthen organisations representing the interests of labour. The insecurity of work especially in the so called ‘gig’ economy needs to be addressed via regulations which require workers to be treated as employees and not as self-employed. The weakening of the bargaining power of unions should be reversed through public policy since this is an effective way to raise wages and reduce the dependence of workers on debt and fiscal transfers from government. The shift in the shares of national income to capital has to be reversed so that employment incomes can be raised and with it increased consumer expenditure. Economic growth nearer to long term trends is essential if employment and income levels are to be restored.

Will the above reforms happen? Time will tell, but the clock is ticking. If structural reforms are not undertaken by government then we will all reap the consequences – and these will not be pleasant.

This is a farce that historians will be talking about until the end of time.

Today’s neoclassical economics was around in the 1920s and it led to the roaring 20s and the Great Depression.

The roaring 20s, roared because of debt based consumption and debt based speculation. All the debt built up in the boom led to the debt deflation of the Great Depression.

Neoclassical economics was revamped but it still has its old problems including 1920s inequality.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

1929 and 2008 stick out like sore thumbs when you look in the right place.

The build up in the ratio of debt to GDP signals the build up of unproductive lending into the economy leading to a Minsky Moment (1929 and 2008).

The debt-to-GDP ratio is still higher than before the Great Depression.

There is a long way to fall, the US needs to tread very carefully.

Outside neoclassical economics.

Irving Fisher produced the theory of debt deflation in the 1930s.

Hyman Minsky carried on with his work and came up with the “Financial instability Hypothesis” in 1974.

Steve Keen carried on with their work and spotted 2008 coming in 2005 (he was looking at the graph above).

1929, Japan 1989 and 2008 are all about debt building up in the economy that leads to a Minsky Moment.

The FED, IMF and OECD don’t see it coming as they use today’s economics.

Blow the bubble, burst the bubble.

Japan 1989

The Asian Crisis

The Euro-zone crisis

Richard Werner’s “Princes of the Yen” tells the story of how Milton Freidman’s “shock therapy” is being applied to the developed world through independent Central Banks.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p5Ac7ap_MAY

Bad economics gains acceptance through a pseudo “Nobel” prize.

The economics prize is a bit different. It was created by Sweden’s Central Bank in 1969, nearly 75 years later. The award’s real name is the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.” It was not established by Nobel, but supposedly in memory of Nobel.”

The “Nobel” prizes helped to give the refurbished neoclassical economics credibility and allow it to push out the old Keynesian ideas (goodbye equality).

http://www.alternet.org/economy/there-no-nobel-prize-economics

In 1997, Robert Merton and Myron Scholes, won the “Nobel” prize for their derivative risk models that minimised risk.

They formed a company Long Term Capital Management using these ideas that blew up a year later posing a systemic risk to the global financial system.

The pseudo “Nobel” economics prize isn’t up too much.

Someone hid the way money and debt work.

Monetary theory has been regressing since 1856, progress isn’t always in the forwards direction.

“Progress in economics and finance research would require researchers to build on the correct insights derived by economists at least since the 19th century (such as Macleod, 1856). The overview of the literature on how banks function, in this paper and in Werner (2014b), has revealed that economics and finance as research disciplines have on this topic failed to progress in the 20th century. The movement from the accurate credit creation theory to the misleading, inconsistent and incorrect fractional reserve theory to today’s dominant, yet wholly implausible and blatantly wrong financial intermediation theory indicates that economists and finance researchers have not progressed, but instead regressed throughout the past century. That was already Schumpeter’s (1954) assessment, and things have since further moved away from the credit creation theory.”

“A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence” Richard A. Werner

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521915001477

In the beginning there was small state, unregulated capitalism.

Adam Smith:

“The labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

“But the rate of profit does not, like rent and wages, rise with the prosperity and fall with the declension of the society. On the contrary, it is naturally low in rich and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin.”

“The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.”

“The interest of the dealers, however, in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public. To widen the market and to narrow the competition, is always the interest of the dealers. To widen the market may frequently be agreeable enough to the interest of the public; but to narrow the competition must always be against it, and can serve only to enable the dealers, by raising their profits above what they naturally would be, to levy, for their own benefit, an absurd tax upon the rest of their fellow-citizens.”

This is what it was like.

Where today’s ideas come from I have no idea.

Exactly the opposite of today’s thinking on profit, what does he mean?

When rates of profit are high, capitalism is cannibalising itself by:

1) Not engaging in long term investment for the future

2) Paying insufficient wages to maintain demand for its products and services

Today’s problems with growth and demand.

Amazon didn’t suck its profits out as dividends and look how big it’s grown (not so good on the wages).

Debt based consumption maxes out.

The Greeks used to like German luxury products until they maxed. out on debt.

The only political party in Spain that includes in its program more or less the same broad reform policy outlined here is the traditional left (Izquierda Unida. IU). The new parties that arised after the crisis: Podemos, (leftist populist) or Ciudadanos (conservative focused on anti-corruption populism), as well as other regional nationalistic parties (new, old, rigth-wing or left-wing) are still very far from focusing on few or even any of these. Their attention is always diverted to some stupid issue.

I believe that in the UK only Corbyn would suscribe those policies. Lafontaine in Germany, Melenchon in France… What about Sanders?

Its a pity.

Thank you, Ignacio. It is a pity about Spain.

Lafontaine certainly does, which explains why Gerd Schroeder ousted him quickly in favour of Hans Eichel. Heiner Flassbeck, formerly of the International Labour Office and SPD, espouses these views, too.

Martin Schulz, who I came across when working in / with Brussels from 2007 – 16, is a neo-liberal, so his loss in October won’t be a cause for regret.

Melenchon hasn’t said much. The French, and for that matter continental, left does not seem to engage much with its Anglo-Saxon brethren where much of the new thinking and dynamism is coming from. As you said, it’s a pity.

With regard to the UK, there are pockets at the Treasury and Bank of England who could / would work with a Corbyn government and push these ideas. Hopefully, Haldane will stick around for when the overpaid, overrated and over here Carney goes home soon after Brexit.

I wonder if Land Value Taxation will ever gain ground. On the one hand the tax on buildings (Council Tax) uses residential house prices that are now close to 30 years out of date (!) On the other hand LVT is a policy that can easily scare older people who want to remain in their large family homes.

I have a generally positive view of it in principle (though I’m no expert and recognise the political impediments – something some proponents realise too and are quick to stress the need for a phased introduction that protects these ‘scared’ groups). At the end of the day it’s probably something neither major party feels is worth the political fight…but in an age of Corbyn, who knows….

Corbyn was very close. It’s been in my opinion the most promising electoral result in years. Spanish liberal press (EL PAIS) doesn’t like him. This is good signal!

” Hopefully, Haldane will stick around for when the overpaid, overrated and over here Carney goes home soon after Brexit.”

Thanks for the chuckle.

But you really should stop beating about the bush and say what you mean! ;-)

And I hope your hope is bears out.

More people over less resources is not a good combination for creating more equality. Unless we start paying attention to real limits and the reality of diminishing returns, not fooling ourselves that more digital currency units represent more wealth, then we won’t improve anything.

We have increasing populations over decreasing highly productive energy and other resources, and we have a monetary system that masks the lack of real profitability and sustainability of our activities and resource exploitation through exponential debt expansion. So we have ever more IOUs circulating, but we have ever less underlying equity. And a monetary system dependent on eternal exponential debt expansion will, like any pyramid scheme, favour the early participants over the later participants, creating greater inequality as it expands. And it will eventually collapse. And even more frightening is that the current expansion of our numbers and our economic activity, whether through monetary or fiscal means, isn’t improving our life quality, but is actually destroying the only habitat and resource base that is available to us.

And as we attempt to fool ourselves into thinking that real economic growth is still an option as the remaining easy conventional oil dwindles away, all we succeed in doing is increasing inequality, frustration, anger and helplessness in the present, and more so in the future. We need to adapt to contraction, not chase further destructive expansion.

I’m not sure whether we even still have time to stop a societal collapse, as our sources of energy and other resources show themselves incapable of supporting the overly complex systems we depend on. Or more importantly whether it’s still possible to reverse the damage to the climate and our natural habitat in order to secure our future survival. But we should at least try. I can’t see us even bothering to try, though.

More equality means, amongst other things less private jets, less luxury resource-consuming items or activities. It also means BASIC goods (housing) and services (health, water supply…) available for those that don’t have. Do you think this is not sustainable? Come on…

The sustainability issue, being important, is another policy issue and I believe it is perfectly compatible with those outlined here

In my view the increasing inequality (across most of the world) is at present principally caused by the nature of our monetary system. The system only works somewhat equitably so long as there is real underlying expansion of the net energy and resources available to society that is greater than or equal to the growth in the number of currency units. Since conventional oil peaked EROEI (energy return on energy invested) of our energy sources has been declining (as well as the productivity of other non renewable resources in energy terms), so we should have been contracting our our economies and our money supply. Instead we’ve created an illusion of growth using a ponzi scheme that concentrates wealth in the hands of those who are first able to convert new debt into assets.

And much more serious is the damage we’re causing to the resources that are vital to our very survival (water, soil, biodiversity, natural habitats, marine food stocks, viable energy sources, mineral deposits etc. are all being depleted at an absolutely shocking rate).

On top of that we have the possibly already irreversible and self reinforcing destabilisation of the climate. Unless we reverse course and set out on a managed decline we’re probably not even going to survive as a species, and will end up causing a mass extinction event.

Whilst I don’t necessarily disagree with your approach to the problem, I think one of the unexplored themes of inequality is that of security versus the current dominant ideology which proclaims that making the economy a precarious proposition for the majority of the population is the only means to raise productivity, profit and coerce the “lazy” into higher levels of working consumption

The question I have is: if everyone could work to obtain a bare minimum level of economic security, would this lead to a knowledge and habit that we don’t need to hoard goods unnecessarily or sedate ourselves against the repressiveness of the current ideology and it outcomes through the high of drugs or mindless shopping-consumption.

Yeah, I think security in the basic necessities is very important. And I also think it would make a huge difference to decentralise and simplify our societies and have more self sustaining local communities with productive tasks that have visible value, and where people actually feel like they serve a real function and mean something to other people around them.

In our current type of system people have largely become relegated to roles as consumption units, with little influence on their surroundings, and are often disenfranchised, alienated and lonely.

Stability over time leads individuals to underestimate risk which leads to more risky activities which then lead to a shock.

Life is a cycle. There will always be ants and grasshoppers. The only thing we can do is try to help each individual evolve according to what their mind and body can offer. And help each other in times of need.

No matter how rich the 1% get, it never seems to be enough. There is a good percentage in the general population that will never feel has enough no matter how much you argue or cajole them.

Instead of looking for stability we should look for solutions that embrace cycles. We should also focus on fairness instead of equality.

Yep, fairness is better word, and should be recruited to the cause. Rather than figthing inequality we should introduce fairness in income distribution and tax redistribution. A previous post on non-profit hospital CEOs’ income was a good example of where to introduce fairness.

Justice as Fairness, by John Rawls, is a useful contribution to this topic. I haven’t finished reading it, probably because I’m always tired when I pick it up, and the reader needs to pay attention while reading this book. Rawls has good ideas about justice and fairness. Here’s a summary of his Difference Principle:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Justice_as_Fairness#Difference_principle

Interesting observations and with quite a bit of validity in my meagre opinion.

However, you (plural, as in we) have to wonder how someone inside of the cycle is able to monitor at what stage of the cycle they are in; does the current cycle necessarily look like a previous cycle; is the cycle the same for everyone in diverse situations and locations?

And I’m not so sure security necessarily means the same thing as stability. After all, security may simply mean being able to deal with unforeseen events like unemployment, injury/illness and so forth without having to die as a result. Stability may always be hard to come by but that doesn’t necessarily mean that one cannot be somewhat secure in the knowledge that there are alternatives means of sustainability.

I suppose optionality is what I’m aiming for in order to be activate stabilisers whilst not necessarily being able to thwart fickle fate.

Anywho, I think it worthwhile to exploring alternatives, if only on a small and local basis. My thinking on this topic is heavily influenced by the positive impacts education (including reproductive education) and other programs have had on women in non-Western societies.

I think you are on to the real thing here.

The effects of Macro-v-Micro.

Jared Diamonds Guns,Germs, and Steel has a table 14.1 that list four types of ways socities are organized and function. Bands are the most accountable and responsible, States not so much.

Today’s discussion got right into the intricacies about Modern Monetary Policy-citing this or that. You too-until this simple but heartfelt(as opposed to headfelt) observation.

Revelatory Complexity is good while Conceal-atory Complexity is bad. I feel like MMP is way too complex and is the later.

I wonder if modern capitalism can be reorganized around micro economies to address:

In our current type of system people have largely become relegated to roles as consumption units, with little influence on their surroundings, and are often disenfranchised, alienated and lonely.

Please feel free to recommend references to me.

Someone needs to explain to me the value of the concept “we.” When the oldest sibling of 10 takes over the family business, refuses to take any input from the others, and runs it into the ground, is it appropriate to say “we ruined the company?”

Unless we start paying attention to real limits and the reality of diminishing returns, not fooling ourselves that more digital currency units represent more wealth, then we won’t improve anything.

So the problem is our fantasy that we can have health care for all? It’s not that banksters have hijacked our (social) economy?

We have increasing populations over decreasing highly productive energy and other resources

So the problem is only where birth rates are high, not where they are declining?

In this context I reckon the ‘we’ is just about everyone to greater or lesser degrees. We’re a social species living in societies, and without society becoming sustainable it’s very difficult for the individual to do so. Our societies are consuming, destroying, depleting, wasting and polluting far too much, and our models of extraction, distribution, production and waste management, as well as living and working patterns are completely unsustainable. We can’t even feed everyone without extremely resource consuming modern agricultural and distribution systems, which can’t even put food on people’s plates without consuming ten times the energy that the food delivers. The principal input factor in the agricultural value chain is oil, as only conventional oil can provide the sort of energy efficiency to maintain the current system.

And it wasn’t my intention to make any specific observations regarding resource allocations, I was only trying to put across my opinion that the wealth concentrating quality of the monetary system we run is creating great and expanding wealth gaps. People will always adapt their behaviour to take advantage of a system they can use to their benefit. And bankers are people taking advantage of a system that allows them to concentrate wealth. I would also add that in my opinion the current system for money creation lacks honesty, transparency and fairness, and it encourages the use of resources today rather than preserving them for the future.

Re population/resources, most places where birth rates are low are already enormously overpopulated… Just imagine what a state Britain will be in, for example, when a real depression hits? It’s basically a resource sink that is draining energy and resources from other places in exchange for empty promises or the ownership of domestic property or productive enterprise.

All valid points. But I think the framing of it as a “we” problem ignores all those social arrangements between “I” and “all of us.” With particular regard to climate change, I have 2 particular beefs:

1. We are not going to all go down together. And those most responsible for global warming are exactly the same ones who are least likely to go down.

2. The “we” framing suggests that if “we” all do our part, “we” can turn things around. Whereas, in order to even begin to turn the ship, some (very many) of us are going to have to challenge, and beat, the relatively small elite faction that continues to drive all of us on the same path as before.

“In my view the increasing inequality (across most of the world) is at present principally caused by the nature of our monetary system. ”

In itself there’s nothing to really argue against in your comment. However, it’s important to deal with first causes: the first causes of rising inequality are the political/economic theories & practices of the last forty years — in a nut shell, neoliberalism. Monetary policy is an expression of neoliberalism. Inequality is not an accident, it’s a planned, successful outcome. We have been tricked, conned & lied to for over a generation. Some have woken up — but far too few. The victories of Trump, .Macron & May show that hiccups aside, neoliberalism is still winning.

I tend to look at it a bit the other way round, though… I take the point of view that both the monetary system and other political/societal systems/conflicts come about due to the the physical environment and other aspects of our environment and our history, and are shaped by the opportunities and restrictions they present.

So I see e.g. the current monetary system largely as a consequence of the declining productivity of our resource base. As we went from horse power to coal power to oil power we created systems to accommodate constant expansion of consumption, and since our systems are now ill suited to reversing course we have instead compensated for the decline of energy/resource productivity with exponentially increasing debts.

This has been a most interesting thread–Thanks to all who have so generously shared your thoughts re: energy, monetary systems, inequality/fairness/justice, sustainability.

“On top of that we have the possibly already irreversible and self reinforcing destabilisation of the climate. Unless we reverse course and set out on a managed decline we’re probably not even going to survive as a species, and will end up causing a mass extinction event.”

Considering the timescales required for GHG emission reductions in order to keep the global average temperature increase in reasonable levels, “managed decline” would mean complete deindustrialization by mid-century. Sounds reasonable.

It’s pretty scary. I sort of still cling to hope, and just seeing a real attempt being made, no matter if it’s futile,would be sort of invigorating. I’m also still not sure if I’ve really gotten my head around the huge consequences of what’s very possibly happening…

We’re all going to die anyway, of course,and people get used to their own premature death all the time through e.g. diagnosed medical conditions. But the death of everyone else too, and most other large species on Earth, is something else entirely.

I probably should clarify: I was being sarcastic. I find the idea of complete deindustrialization as a solution to global warming utterly ridiculous. Especially considering the implication that the efficiency of global economy in terms of GHG emissions/GDP cannot be improved. Which from all I’ve seen is somewhere in the negative numbers. It just seems to me trying to solve the problem with the most pain possible.

To gauge the popular ideology, all one has to do is walk into a Home Depot.

Environmental concerns have gone up by leaps and bounds yet…

– many of those retreating to their gardens are landscaping with fake rocks and fake grass.

– focusing on pretty and non native plants. Growing flowers instead of food.

– whispering how they are getting their banned pesticides to keep their grass weed free

– heating and cooling the outdoors

– all kinds of smoke producing backyard fireplaces.

To me, it sure looks like environmental destructive consumption is going exponential instead of dropping.

Yes, and let me add the environmentally destructive activity of pouring ones half-eaten, mega-cup, sugar-laden Starbuck’s latte’ onto the asphalt parking lot. Soon to be flushed into the nearest river (ocean, in my locale) to feed the algal bloom and degenerate the natural ecology for piscivores.

Thank you for sharing, Yves.

“Where QE is continued it should be used to serve the interests of the country and not the rich few, and this would mean using monetary expansion for financing public investment in a sustainable way – both social and economic investment.” This is an idea floated by Shadow Chancellor John MacDonnell and his fellow traveller Adair Turner.

Cohen’s former colleague, Professor Mariana Mazzucato, is an adviser to the Scottish government and has worked with the Labour opposition. Her https://marianamazzucato.com/entrepreneurial-state/ has influenced the Bank of England’s Andy Haldane and MacDonnell.

There’s a luxury shopping outlet in Bicester, north of Oxford and not far from where I live. The complex is the largest employer in the area, but few employees are local. As the centre is just off the highway and railway, it attracts many tourists from London, especially Chinese, Arab and Russian visitors. Retail staff with linguistic skills are favoured.There are three Burberry’s shops within a hundred metres of each other. Entrance is controlled as numbers can be overwhelming. The outlet does so well that it employs multi-lingual staff at Marylebone station to help tourists get on the train from London. In short, Bailey has, or had, to do very little. A smirking chimp from nearby Cotswold Wildlife Park at Burford can probably do the job of catering to the rich.

The idea of ” People’s QE ” was developed by Richard Murphy whose blog Tax Research is required reading alongside Naked Capitalism. Should Corbyn become PM at some time in the not-too-distant future it is an idea that seems likely to feature in his economic policy . The details have yet to be worked out, but one aspect I would urge for consideration is the ” Citizen’s Committee , or Jury ” where projects with major local impact are concerned in order to break down the over centralised state in the UK .

I agree with Yves comment in her third paragraph, about political action, but I think the lack of political action runs much deeper than mere choice. The role of QE after 2008, on top of the tax-cutting and the adoption of broad-based regressive taxes since the 1970’s really put a rocket under inequality. QE is the almost perfect refinement of Keynesian stimulus in this regard to counter a cyclical downturn. It has two key defining characteristics.

The first is it directs the stimulus to the asset holding class for their benefit, while ensuring the working class (using the Poor Law definition: anyone not sufficiently wealthy to own an independent income) not only do not benefit, but are further enmeshed in the complexity of the economic system. This means the true costs are at best difficult to quantify and more often just hidden. This argument takes the form that solvent banks and inflated asset prices are good for everyone, and any alternative action (TINA) will hurt, for example, retirement incomes.

The second defining characteristic is that the stimulus was moved off-budget into the opaque realm of independent central banks. This had the huge advantage that stimulus could be unbounded while the failing budget position of traditional fiscal budgets within the cyclical downturn could be used to further lambast the working poor with real cuts to the social wage: that is, those services provided to working people by the public sector that mitigate against social exclusion, including health care, education, social security and essential social infrastructure.

Unfortunately, most criticism of this development is conducted by heterodox economists as a technocratic argument. There are valid reasons for this, including the perceived need to be taken seriously, and to provide considered and evidence based conclusions. But it completely misses the political argument; in fact, it often obscures it.

Neither Bernie Sanders nor Jeremy Corbyn had a compelling political argument to assail QE and inequality, and most lesser leftist parties around the world appear to be completely ignorant on such matters. In Australia, the left tends to revert to 19th century Marxian analyses: itself now both irrelevant and adding to further political confusion. The imbroglio surrounding the leftist Greens Senator Rhiannon is a current example.

This leads to the conclusion that the political argument for change has still not appeared, and that, at this stage, Wolfgang Streeck’s excellent if depressing analyses in ‘How will Capitalism End’ is holding true: that late-stage capitalism will collapse under its own excesses, and not from a considered and well executed political movement to overturn it.

This is very well stated. Agree with everything except the title of Streeck’s book. I know him a bit and like him a lot, but the title should have been, “The End of Modern (or Industrial) Capitalism.” He is talking about the end of post-WW2 capitalism, not the end of 1700-onward capitalism, which certainly seems likely to continue.

Also agree that it is very well stated and believe that glmmph may have been referring to this essay:

https://newleftreview.org/II/87/wolfgang-streeck-how-will-capitalism-end

The only good thing about QE is that it demonstrates in practice that governments/central banks CAN “print money”. That governments are not a “household” writ large.

Of course the vast majority of average citizens can’t even comprehend the idea. I’ve tried to explain QE & MMT in outline & the response i usually get suggests that i’m mad, a smart arse or both.

There really is a crying need for economic education…but let’s not hold our breath….

How right you are! – on all counts.

But given your pessimism (which I share) concerning the likelihood of *widespread* economic education, isn’t what’s required even more urgently the complete eradication of the almost universal *mis*-education of the supposed elite, up to and including those demigods with feet of clay the winners of the so-called “Nobel prize” in economics? As has been persistently argued in certain quarters for a long time now, economics as taught in the academy (that is to say “mainstream” economics) is grounded in completely fallacious premises.

It might help (though not overnight) to start by correcting that, and it ought to be doable.

Well, it ought to be doable but don’t underestimate the magnitude of the challenge. Precisely the same arguments against unbelievable economics have been made since the 1940s and the discipline seems as strong, and single-minded, as ever. And in the intervening years, literally millions of new economists have been trained (only) in this tradition, and alternative trajectories in economics that formerly existed in various European countries and Japan appear about extinct (though perhaps making a small comeback?). As Mirowski points out, virtually every central bank, university economics department and economics “research” institution is populated only by people trained in this tradition, and every traditional career path for an economist involves working in this tradition. The one thing that has clearly been proven in economics is that being wrong on the facts has virtually nothing to do with epistemological or career success.

I have done most of my academic work in sociology and my guess is that there are probably fewer than 1000 sociologists worldwide working on these issues. Probably the same for political scientists. Perhaps more in geography but I don’t think geographers will ever really have economic credibility.

The one interesting academic trend worth following is the Chinese approach to economics, if there is one. The economics department at my local U is full of Chinese graduate students being trained in the neoclassical tradition. Presumably, they will follow in this tradition as all others have. But i wonder.

LiW

You clearly have good grounds for your conclusions, but what a doleful prospect!

Are there any grounds at all for optimism, in your opinion? If not – next Great Financial Crisis (only worse), here we come.

Time to roll out the tumbrils, with mainstream economists and central bankers as first passengers?

. . . One point of differentiation is that the US tax system is progressive but our government spending is regressive (as in the transfer payments to lower income groups pale compared to subsidies to capital-owners via our many forms of socialism for the rich).

The most recent example is the great state of Michigan subsidizing Amazon’s new warehouse near Detroit. Only $5 million this time, $5 million that other non- Amazon taxpayers in the state have to come up with, and the reward is Amazon’s promise to exploit 1600 new workers in it’s new soul and physical self destroying modern satanic mill.

Amazon is promising to create at least 1,600 new jobs, but needed state assistance to help pay for “substantial road and other infrastructure improvements,” according to a Michigan Economic Development Corp. memo to Strategic Fund board members.

Welfare and socialism for Bezos. Capitalism for the peasants, and no money to fix Flint. Priorities!

Absolutely!! One has to have the right order of priorities and know where to feed at the trough.

If only there were some new targets for union organizing that could not just pick up and move to China…

1600 jobs: sure. I’d better closer to 600….

While inequality is an economic issue, it seems to me it has no “economic” solution. It is a issue of morality. Inequality can not be discussed without discussing the national debt.

Make a list of the ten most pressing issues facing the US (or the UK). Surely the national debt must make the list. The interest payments made on the national debt are nearly equal to the defense budget, and enough to address many shortcomings of government services.

More importantly, every day the US is charging tens of millions of dollars to the credit card of the next generation. Frequently raising the debt ceiling is one of the few things both parties support, while common sense dictates that the debt increase is or will become unsustainable.

Reducing the national debt requires unpopular measures opposed by the constituency of both parties, making it politically impossible. This leads to an inevitable conclusion: the US is unable to govern itself in a responsible manner due to a political stalemate. The issue of inequality is important, but secondary the the existential crisis of US democracy.

I don’t think the national debt is as much a problem as it is a strawman that keeps us from actually addressing income inequality.

Most of the national debt is owed to ourselves, with a better monetary policy, I think that we can manage that just fine. MMT is just one example.

But what the “debt argument” does is keep us thinking we need to impose more austerity on ourselves, which drives down wages for all but the top echelons (who make their money off of our debt), and it keeps us thinking that we just don’t have the money to do great things, like major projects that employ people, like provide adequate healthcare (in the US), like actually addressing the major economic flaws of neoliberalism……

I’m not an economist or a great writer, but I think Yves and others can (and have in the past) explain to you why holding on to this idea that debt is the problem is wrong…..

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/real-fiscal-responsibility-today-radio-and-tv-show#/

Government debt isn’t “owed to ourselves.” It’s owed to very wealthy people and the largest, most powerful corporations/business entities. As noted in the original comment, the amount of money being transferred to very wealthy bondholders via taxes paid by working people (regressive payroll taxes at the federal level and regressive VAT/sales taxes at the state level) is a significant budget amount at every level of government.

The US and each of its states is a major economic player with tremendous power to tax. The same is true of every developed economy across the globe. If they want to spend money (anti-austerity), all they have to do is tax people (especially wealthy people via taxes on rent incomes, interest, dividends, capital gains and other intangible income sources) and then spend the money. Using debt financing that sends billions of dollars of interest income EVERY YEAR to the wealthiest families and largest, most powerful corporations is partly what has led to significant inequality between the highest and lowest income/wealth levels of society.

I am also not an economist, but to me MMT sounds like a theory used to justify debt while divorced from any moral foundation.

Can someone explain to me why it is OK to charge hundreds of billions of dollars of debt to the next generation? The argument that we can “grow ourselves out of debt” may have been true in the 1970s, with China and the EU in the mix this is no longer easy or likely.

The argument that “we owe the national debt to ourselves” is not quite correct. The national debt is “owned” by the next generation.

If the current national debt is no problem, when will it become a problem? Can the US spend another $10 trillion on, say, education and infrastructure, (thereby increase interest payment on the total debt to, say, a trillion a year), and still manage the debt?

Note that the growth in the national debt in the past 30 years or or shows a remarkable similarity with the increase in inequality. I do not claim a causal relationship, but I am quite sure that adding debt without a clear plan or even will to stop it from rising further is producing a lot of bad karma. Hence the majority of Americans think the country is going in the wrong direction.

“but to me MMT sounds like a theory used to justify debt while divorced from any moral foundation.”

Associating debt with morality …

I think I see your problem.

Would you buy a house and let your children pay the mortage? If there are no consequences to increasing debt without any plan to reverse course, why don’t we give everyone a basic income and free heathcare?

You’re missing the role of the Federal Reserve. They electronically declaring money into existence, which enables the government to directly spending it without having to borrow it from anybody else first. It still officially hits the books as debt due to the way the Federal Reserve issues new money, but in reality, the government will never have to pay it back. The Federal Reserve will simply roll the debt over into new loans that are even bigger. There is no limit to how long this can go on.

For experimental proof, see the example of Japan. The Bank of Japan (their counterpart to the Federal Reserve) has printed enough yen to allow the Japanese government to borrow their GDP several times over. And it’s never collapsed this entire time. The debt is not being repaid. It will never be repaid. It just gets rolled over into newer, bigger loans.

Of course, the astute economic observer will note that Japan’s example probably isn’t the one we want to follow. When their real estate bubble collapsed back in 1991, the BoJ dropped interest rates to nearly zero and printed yen by the trillions, issuing giant loans that they were perfectly willing to roll over into larger future loans indefinitely. [Much like the Federal Reserve did in 2008.] And did Japan’s economy roar back to life? Hardly. They entered a period of economic malaise called the “lost decade”, which is arguably entering its 27th year.

Once the debt that will never be repaid is subtracted out of the equation, it essentially boils down to the government directly printing money to fund their own spending. Doing this even more is frequently advocated as a way to stimulate the economy, but the example of Japan (and our own, from 2008 onward) indicates that there are limits to the approach.

I’m not sure why we do the same thing as the Japanese and expect different results.

The point is to outgrow the debt and the deficit. Austerity deepens recessions and weakens recoveries and without it the debt would have been smaller.

The Eurozone has shown this correlation when you compared how much stimulus / austerity they did and compare the national debt to GDP ratio. The literature apparently also shows that yes austerity is contractionary. Cases where it seems otherwise such as Canada are because of confounding factors (they pursued austerity at a time when the Canadian dollar depreciated by 40% giving them a boost in exports).

There is one way to do stimulus without increasing the debt which is using the balanced budget multiplier. Increase taxes on the rich to pay for a stimulus. Tax burden goes up, growth strengthens, but the debt stays where it is. However, it’s less effective than a stimulus financed by borrowing and the rich will resist it politically.

As for the next generation, most US govt debt is held by Americans and will be paid back to Americans. Failure to stimulate the economy enough by borrowing since 2008 has meant the next generation will grow up in an economy smaller than it should have been.

Much of the support for austerity and opposition to borrowing isn’t based on economic ignorance, though. It’s as an excuse to cut govt spending to reduce the deficit and then use this later for tax cuts.

> The point is to outgrow the debt and the deficit.

In our debt based system, that is an impossibility. Moar debt as a solution to too much debt is similar to arguments that the answer to too many guns is more guns.

I agree with Saltcreep’s comments above. In essence, just do less.

The evidence shows that you are wrong. It’s analogous to the private sector: do you not accept that a business can borrow to invest and repay its debt using the income which this generates?

Seems to me that #3 is the key to all the others, and it’s really hard to see how that gets changed. Remember when people — sitting politicians even! — talked about campaign finance reform?

The best hope for reining in the gift of elected branches is, or should have been, the judiciary. Alas, Dems have never paid enough attention to stocking it.

But then, I speak as if they wanted to.

What I think is missing in this list is to take on monopolies such as utilities, big pharma, big food, big tech and so on.

Public banking is also missing.

The point is, it is useless to raise wages if someone is going to suck them away: real estate monopolies or financiers.

I very much agree with Cohen’s point #1. QE and ultra-low interest rates by national banks have been a disaster from an income inequality standpoint. After all, income inequality got worse MUCH faster under Obama than it did under Bush: http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/04/growth-of-income-inequality-is-worse-under-obama-than-bush.html. And while my opinion of the modern-day Democratic Party is quite poor, I’m not convinced that accelerating income inequality by a factor of THREE was one of their policy goals. The blame really belongs to the Federal Reserve.

After all, the Federal Reserve explicitly embraced “asset inflation” as a policy objective, hoping that the “wealth effect” would stimulate the general economy. In other words, make people who already have lots of assets (i.e., the rich) wealthier, so that they spend more money. This was “trickle down economics” in its purest form. The rich got richer, and the poor got slammed with a housing affordability crisis.

And to Cohen’s four points, I would add a fifth: Increasing monopolization of industry. When companies have a monopoly (or near monopoly) on a product, the price becomes “what will the market bear?” instead of “how much does it cost to produce?”. This is particularly problematic in the technology and pharmaceutical industries.

Heck, even the employees of monopolies suffer. If you’re unhappy with your wages and you work for a monopoly, there is no competitor nearby who might be interested in hiring you for your specific skill set. You generally have to switch industries entirely, where your experience base is less relevant. Lower wages await.

.

You could say the same for all of economic and social history in the US. Independent subjects in the UK, they are largely absent in the US. No surprise: McCarthy-era loyalty oaths for academic staff, succeeding less formal restrictions in effect since the Progressive Era, were common even in the early 1970s.

As you say, the products of serious economic and social history are often not pretty, barring hagiographies of figures like Henry Ford, absent the antisemitism, and friendly assessments from the dean of American business history, Harvard’s Alfred Chandler, who never seems to have studied a robber baron and his practices he didn’t approve of. America seems to regard its form of capitalism as a religion, and does not invite critical research into its origins and practices.

Piketty’s work is very respectable and helped to raise awareness. But I disagree with many of his aggregate treatment/calculations. The supermanagers’ stock compensation goes to Piketty’s crucial capital/income ratio as income instead of returns on capital. One thing is that from the firm’s accounting perspective top executive stock options and so forth are employee remuneration. And, yes, the supermanager is an employee,a worker- an uncritical,bare, and useless classification which matches that one of the junior assembly worker. But when a few position holders have the power to strongly influence-and in some cases ,in praxis, decide- their own appropriation of wealth from the corporation they are “employed with”, the social scientist should not fall victim to the reproduction of categories applied by those who are categorized.

‘But when a few position holders have the power to strongly influence-and in some cases ,in praxis, decide- their own appropriation of wealth from the corporation they are “employed with”…’

Exactly!

A beautiful example of the quickness of the hand deceiving the eye (the hand in question being the beneficiary’s).

As always, ask:- “cui bono?” Piketty has deceived himself.

[cut-and-paste]

How to raise US labor unions from the dead — tomorrow — practically and practicably:

In BALLOT INITIATIVE states it typically takes the number of registered voter signatures equal to 5% of the vote in the last governor’s election to put your initiative on the ballot. (OR, CA, MO, MI, OH, OK, CO, NE ND, SD, MT)

Check the numbers of who should line up around the block to sign an initiative making union busting a felony:

— nationally, bottom 45% income share has dropped from 15% to a penurious 10% over two generations (as per capita income doubled).

Does that mean bottom 45% incomes are ahead absolute terms: 66% of twice as much? Not across the board: incomes are sorted on a slope. That leaves maybe 15% behind in absolute terms: why we have a $7.25/hr fed min wage — down from $11/hr (adjusted) in 1968.

Check the numbers of who should line up around the block to propose a higher state minimum wage:

— nationally, 45% of employees earn less than $15/hr.

We could conceivably get 5% of registered voters (1% of population) out there collecting signatures! :-O

Some states like California put a winning initiative on the law books immediately. Most, allow the legislature one shot at approval. If it doesn’t approve the measure goes back to voters for final decision.

In California you write in plain language what you want your initiative to say and a state legal office will put it into proper words for a state law.

In California circulators (signature collectors) may be paid employees. This has led in recent years to initiatives becoming the play thing of billionaires — the opposite of the original intention.

If initiatives can quickly and easily take our world back, then, Fight for 15 and labor unions and others now have a new, all critical mission: register and sign up as many voters as possible.

Raising the issue of making union busting a felony to a high level of national consciousness should prompt legislatures in progressive states to finally wake up and face what they need to do — what we all need them to do. (WA, IL, MN, NY, MA, VT, CT, RI, PA, MD, VA, etc.)

http://elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov/ballot-measures/pdf/statewide-initiative-guide.pdf

Would the US and the world be materially worse off if there was not a gigantic tax cut for the top tier? If so, how, by how much, and whom (as in Who, Whom?)

Would the extra taxes collected crowd out some investment , or some consumption, or some asset transfer to hoarder places? (I started to write harder places to reach but somehow like hoarder places better.)

The above seem like simple questions that get overshadowed by the ideologies of modern media and academia discussions. Is it possible to estimate that each $100B in extra tax would reduce top tier investment by $30B, consumption by $20B and hoarding by $50B, or some other quantifiable amounts, say?

Then what happens to the flip side? The lower taxes or higher transfers or whatever to the lower or lowest tier. Is there some great cosmic utility function that provides some metaphysical certainty about the machinations? Or is that all smoke and mirrors to hide donor and lobbyist and in-power rewards? My suspicions tend toward the latter, but then again, these days I have even more to suspect about all pronouncements from Washington and Wall Street.

Help.

“Populism and the rise of extreme parties of the left and right will inevitably lead to change, but why wait for this to happen”

Trumpism could be taken as the populist extreme right wing version in the US. The appointment of guys like the Secretary of Treasury and the Chief of Economic Advisor unequivocally indicates that particular types of big capital interests are well secured

Walter Scheidel’s book “The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century” has been mentioned in NC before (Water Cooler 1/26/2017, Notes From an Emergency: Tech Feudalism, 5/19/2017, Water Cooler 3/13/2017, Water Cooler 2/6/2017, Links 1/27/17)

I have not read the book, but here is a link to a lengthy article from Scheidel dated June 19, 2017.

https://aeon.co/essays/are-plagues-and-wars-the-only-ways-to-reduce-inequality

“History offers very little comfort to those in search of peaceful levelling. To be sure, it is perfectly possible to reduce inequality at the margins: if Latin American countries have done it, the US, UK or Australia certainly ought to be able to accomplish the same, using an array of policy measures, from fiscal interventions, basic incomes and the targeting of concealed offshore wealth, to carefully focused investment in education and campaign finance reform. However, policymaking does not take place in a vacuum, and not everything that worked well for the postwar generation, say, could be easily implemented in today’s more globally integrated, competitive and deregulated environment. Throughout history, truly substantial compressions of inequality invariably had much darker origins, and no similarly powerful alternative mechanisms have since emerged.”

My short summary, is that historically inequality decreases when there is a new relative shortage of people (workers) caused by some natural/biological or human caused event.

To change anything, it would take a USA leadership class with many people of influence convinced that something needs to be done about inequality.

.Instead we have leaders of even the more “inequality concerned” branded political party that appear most interested in increasing their personal wealth as illustrated by the Obama and Clinton clans.

Interesting that in an essay from the land of Keynes there is no mention of public works or increased public employment. From articles linked here in the recent past, it looks like police, fire, and medical services are all feeling the pinch of austerity, and it’s looking like there’s a lot of public housing that either needs to be upgraded or rebuilt.

Is there a feeling in the UK that there are enough public employees and public projects already?