By Jianwei Xu, an associate professor at Beijing Normal University, and also works as an affiliate fellow at China Academy of Social Science and a youth member of the China Finance Forum 40. Originally published at Bruegel

Pharmaceuticals are a hugely important industry for the EU and the UK. The sector creates thousands of jobs, billions of euros in exports, and is Europe’s most research-intense industry. But will Brexit mean for pharma? Border delays, disruption to R&D and regulatory divergence all pose hazards.

Despite numerous debates about the impact of Brexit, the pharmaceutical industry seems to be less eye-catching than other sectors like the manufacturing supply chain and financial services. However, pharmaceuticals are one of the EU’s most important and fastest-growing industries, and they benefit greatly from EU integration.

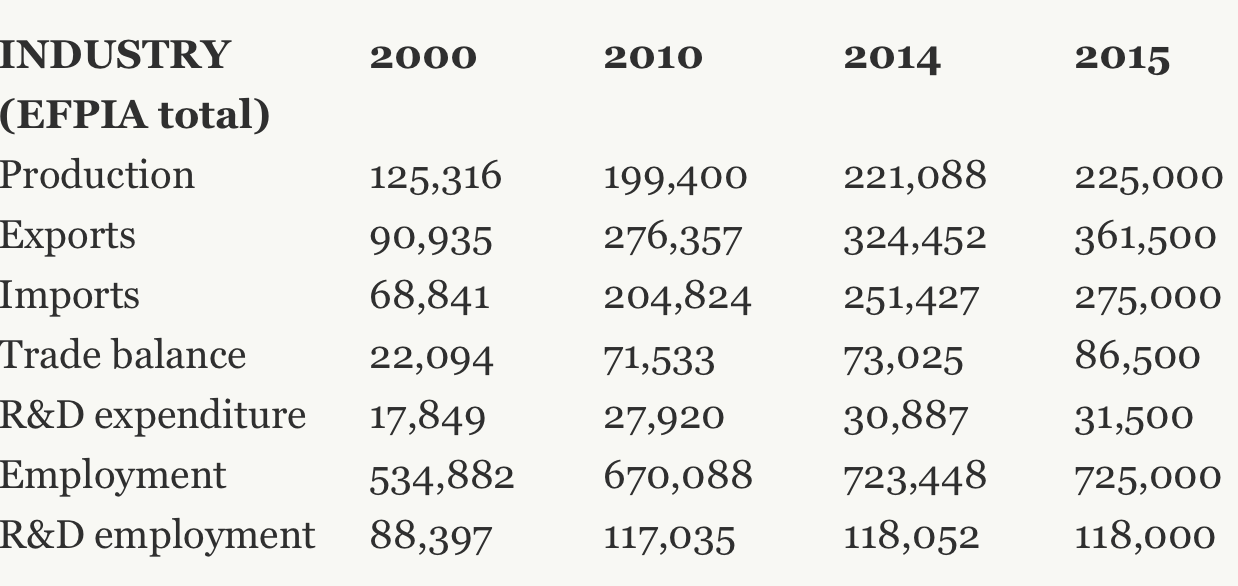

Pharmaceutical in the EU has increased from €125 billion to €225 billion over the past fifteen years. Employment in the sector also grew dramatically from 535000 to 725000. The pharmaceuticals sector has also become very advantageous for the EU. Exports of pharmacy products have more than tripled over the past fifteen years, with most of these gains obtained from extra-EU transactions. Pharmaceuticals are also the third largest industry in the UK, contributing 10 percent of the UK’s GDP, with an employment of 73000 people and a trade surplus of €3.3 billion.

Table 1: The rapid growth of the European pharmaceutical industry

Source: “The pharmaceutical industry in figures”, 2016, European federation of pharmaceutical industries and associations.

The rapid advance of the pharmaceuticals sector over the past decade can be closely associated with the integration of the EU trade chain. In 2016, around 67% of the EU’s exports of its products were intra-EU exports; 52% of the EU’s imports of its products were intra-EU imports. According to EFPIA figures, among the EU member states the UK is undoubtedly a key player, constituting 10% of the EU’s total production and employment. Moreover, the UK runs a trade deficit of €114 billion against the other EU27 countries, implying that it is a major destination for EU pharmaceutical products.

Non-tariff barriers such as the possible establishment of physical border could have negative effects on pharmaceutical trade

Fortunately, the EU has long adopted zero most-favored-nation tariffs even for international extra-EU transactions for pharmaceutical products. So the worst scenario, even in a hard Brexit where the EU and UK treat each other in the WTO multilateral framework manner, would not add a specific tariff burden on pharmaceutical trade.

However, tariffs are not the only barrier to trade. There is also a possibility that other types of non-tariff barriers could be created to hamper pharmaceutical trade. In particular, with the strengthening of immigration control, border checks might be resumed which could create delays in transferring pharmaceutical products to/from the UK. Longer lead times and increased paperwork caused by these customs bottlenecks could affect service levels and margins – especially for pharmaceutical products, which have a short shelf life. Evidence has shown that, for time-sensitive industries, every 1 hour of customs delay adds 0.8 percentage points to the ad valorem trade-cost rate and leads to 5% less trade. This means that perishable pharmaceutical products are likely to cost more for UK residents, especially in the case of emergency.

The establishment of a physical border also matters particularly for Ireland. Ireland is the only country that shares a land border with the UK. Although it is hard to say what will eventually happen in the event of Brexit until the final post-Brexit model is determined, the risk has been mounting since Theresa May’s report signaling a hard Brexit. Establishing an Irish-Irish border would mean that Irish pharmaceutical products need to go across the UK border twice before entering the rest of the EU. One solution to avoid this additional processing cost is to construct a common border for two countries, which was already the case for passengers from 16 countries such as China and India to enter the region. But that undoubtedly means additional costs for Irish pharmaceutical consumers.

Disruption of Research and Development (R&D) Activities

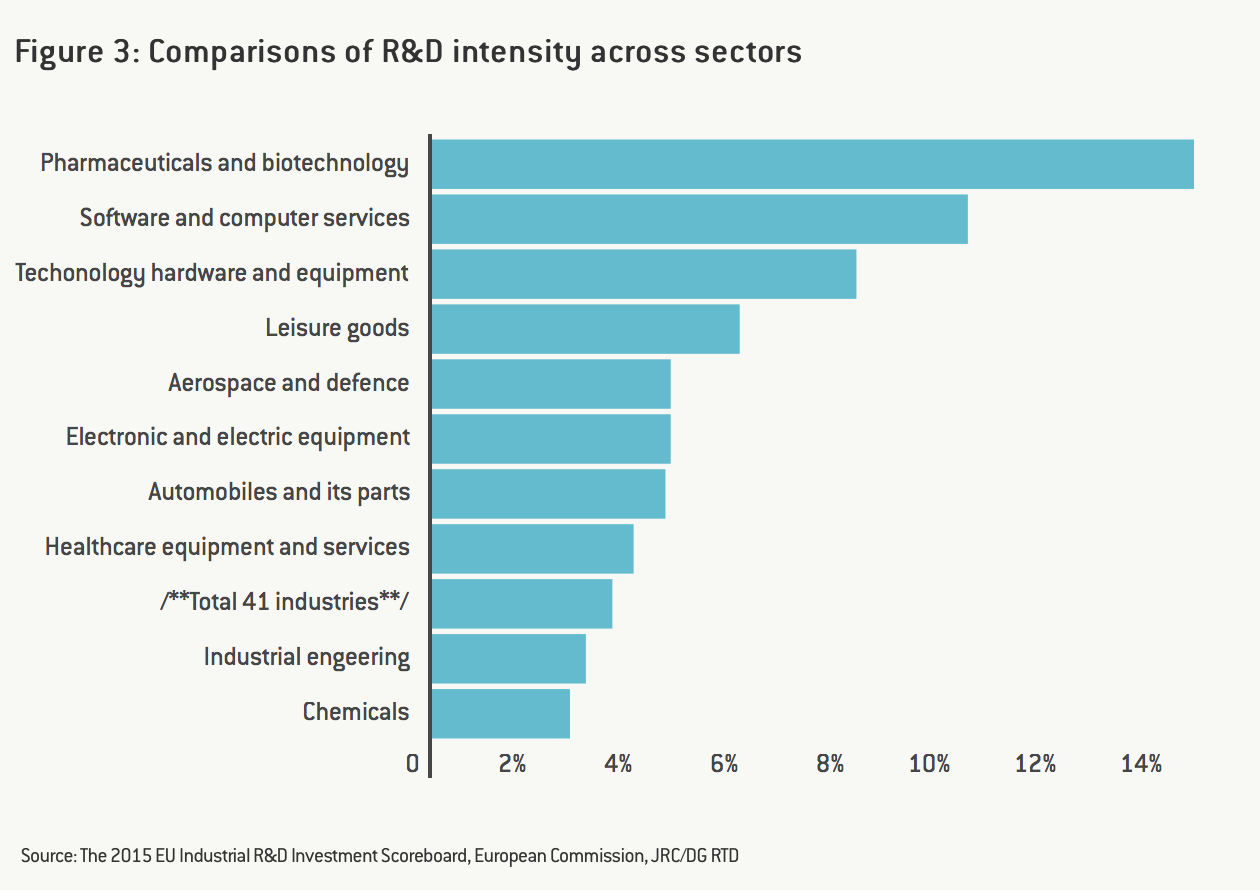

One of the key characteristics of the pharmaceutical industry is its high intensity in research and development. Figure 3 shows that the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sector accounts for the highest R&D intensity in the EU, even higher than the software and computer services sector. Eurostat data also indicates that the pharmaceutical industry has the highest added-value per person employed.

Within the pharmaceutical industry, UK has long been a center for research and development (R&D) activities. In 2015, it contributed approximately 20% of the EU’s total R&D, only slightly lower than Germany and France. As Maria Demertzis and Enrico Nano highlight, these research and development activities rely on two key factors: skilled labour supply and research funding. Both factors could be at risk in the post-Brexit era. For the former, the UK has attracted a large number of skilled workers from abroad, most of which are EU citizens. For the latter, the UK gains more research funding in the current system than any other country. Therefore, Brexit could undoubtedly have a negative impact for both factors in the pharmacy industry.

I find it hard to see that trade barriers will make much of a difference in pharmaceutical trading. However, the core issue for the UK will be in research. Uncertainties over legal rights and status will greatly undermine the ability of UK universities to attract the top talent in students and researchers and its highly unlikely that a UK goverment will be able to pay for the current level of research (especially under a Conservative Government). I don’t think it will be a major catastrophe, just a slow reversal leading to a decline relative to other European countries.

Incidentally, it was reported yesterday that Premiership clubs are finding that foreign talent are insisting that their contracts be paid in Euro, not Sterling. When footballers are losing faith….

well, they all took 10% paycut in the last 12 months (cause even the English ones likely spend most of their money outside of the UK directly or indirectly).

I would think that the R&D budget doesn’t have to take a hit per se. As a sovereign spending in it’s own currency, the Brits can decide what level they wish to support R&D internally without EU funding. While losing foreign labor will be a hit, no question, raising the pay and prestige and career outcomes of the Ph.D. track certainly won’t hurt. Like other industries, the academic biotech R&D efforts rely on an army of underpaid foreign workers because the pay is so low. Native workers rightly decide to spend their efforts in other industries or if they enter that tract leave direct R&D work entirely because of low career prospects or high turnover in jobs. If the pay and career outcomes were better, you would see more native Brits focus their efforts there.

The ability to deficit spend is not unconstrained. It is limited by inflation. With a Brexit, the pound will decay further. Higher wages and higher spending mean higher inflation.

Hmm anything bad for the pharmaceutical industry is probably a good thing for everybody within its reach.

This article is garbage.

The authors claim that Ireland will have trade issues because, with the Irish-UK border and UK out of the EU, “Irish pharmaceutical products need to go across the UK border twice before entering the rest of the EU.” Last time I checked, the Irish could put stuff on boats and bypass the UK entirely…

Another major point, overlooked by the authors, is that the UK business climate and regulatory regime are likely to be far more favorable to pharmaceutical companies than that in the EU. The horrendously heavyhanded, unaccountable and generally non-productive EU bureaucracy was one of the main reasons behind the push for Brexit in the first place.

@Wisdom Seeker – One point of disagreement: Putting pharmaceuticals on boats exacerbates the issue of short shelf life. The details are in the second paragraph under “Non-tariff barriers…” above.

Britain and California are the hub of genetic engineering, the main obsession óf biotechnology.

Throw in Canada and the rest of the Five Eyes /Commonwealth, and you have a fast track to a Brave New World in which GMOs completely dominate the foodchain.

Keeping them under control was one of the few successes of the German led EU – Germany has a strong naturist culture, in common with Russia.

The latter is now publicly committed to GMOs – free agricultural policy, which will find a ready market.

The manufacture of generic drugs will continue apace as the TTP control over ‘intellectual property’ weakens, without heavy US /UK lobby presence in Brussels.

Hopefully there will be a thorough clean out of current apparatchiks in the Commission and a return to real standards for general human welfare.

Russia is fortunate to have a Putin, the EU is very ill – served by comparison.

New faces are needed, and more e resolve.