Yves here. We first wrote about the dangers of global-warming-induced ocean acidification in 2007, with the key parts from a post by Stormy at Angry Bear:

Global warming skeptics often praise the benefits of global warming. After all, the opening of the Northwest Passage means better trade routes. CO2 in the atmosphere means healthier plants. And who in northern latitudes would not wish for balmier days?

But there are side effects to our love affair with CO2 that are not often mentioned. In fact, whether the earth cools or warms is absolutely irrelevant to these effects. I repeat: Absolutely irrelevant.

One of the most startling effects is the acidification of the oceans. Since 1750, the oceans have become increasingly acidic. In the oceans, CO2 forms carbonic acid, a serious threat to the base of the food chain, especially on shellfish of all sizes. Carbonic acid dissolves calcium carbonate, an essential component of any life form with an exoskeleton. In short, all life forms with an exoskeleton are threatened: shell fish, an important part of the food chain for many fish; coral reefs, the habitat of many species of fish….

The formation of carbonic acid does not depend upon temperature. Whether the oceans warm or cool is irrelevant. Of concern only is the amount of CO2 that enters the oceans. And, as readers of my last thread might remember, we are accelerating our creation of CO2 at an alarming rate…

According to one estimate, between 1750 and 1994, oceans absorbed 118 billion tons of CO2—and we were just starting serious CO2 production. As anyone with a fish tank knows, as the Ph falls, the water becomes more acidic. Fish life becomes more and more problematical.

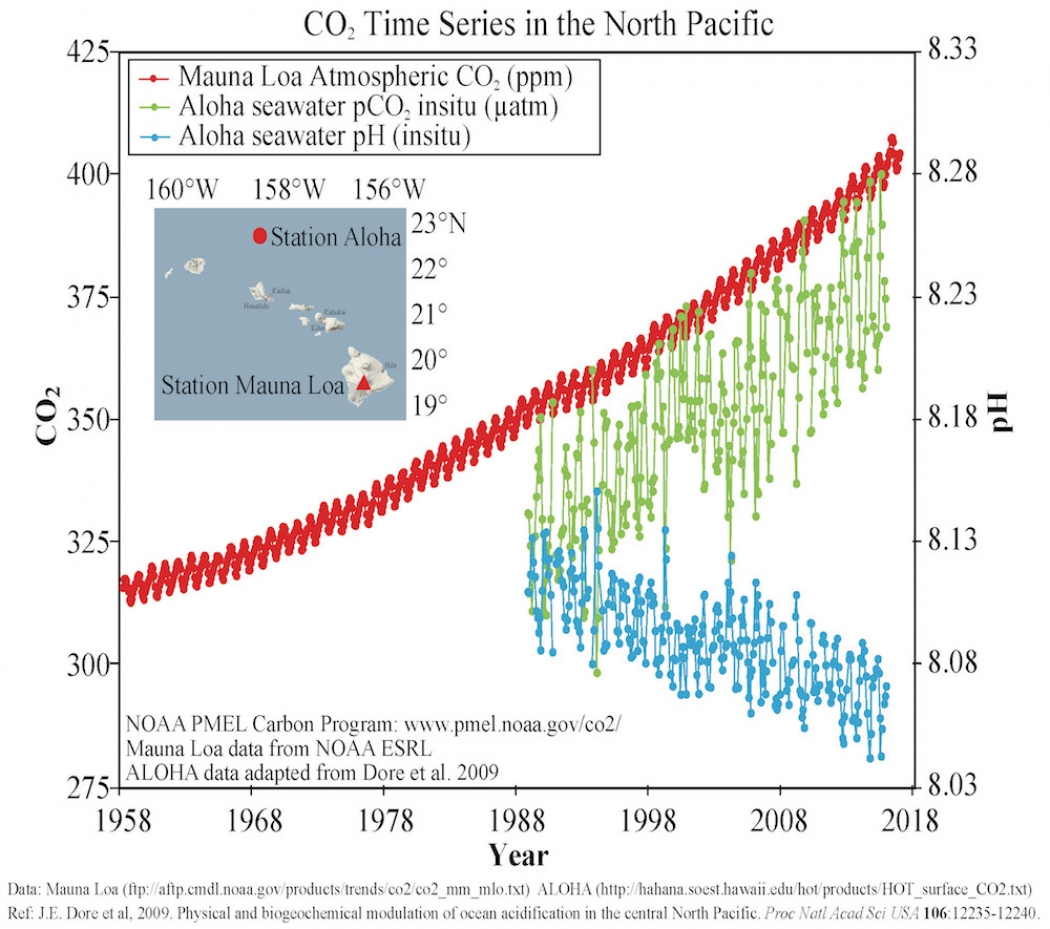

This absorption has made the world’s oceans significantly more acidic since the beginning of the industrial revolution. Research published last year by Mark Jacobson, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University, indicated that between 1751 and 2004 surface ocean pH dropped from approximately 8.25 to 8.14. James Orr of the Climate and Environmental Sciences Laboratory further estimated that ocean pH levels could fall another 0.3 – 0.4 units by 2100.

In fact, by 2050,

…there may be too little carbonate for [in the Pacific] organisms to form shells as soon as 2050.

Since 1990 alone, Ph levels in the Pacific have dropped .0025. Such a drop may not seem significant until one understands Ph levels.

By Andrea Thompson, a senior science writer at Climate Central. Originally published at Climate Central

Hot spots of ocean acidification have been found in the waters that wash onto the shores of the West Coast, a major concern for the region’s billion-dollar fishing industry as well as the region’s potentially fragile coastal ecosystems.

A new study of a 600-mile span of coastline found some of the lowest pH levels ever measured on the ocean surface, showing that significant acidification can be found in waters right along the shore.

One of the sensors used to monitor levels of ocean acidification along the Oregon coast. Oregon State University

“Ocean acidification has made landfall” across the entire area, coauthor Francis Chan, an Oregon State University marine ecologist, said.

But the news from the study, detailed May 31 in the journal Scientific Reports, isn’t all bad: Some areas had more moderate pH levels, and both these and the hot spots persisted in the same areas from year to year. This could give researchers and officials looking to protect marine life a map of where to concentrate efforts to mitigate against rising ocean carbon dioxide levels.

Ocean acidification is the often-overlooked partner to global warming and is driven by the same human-caused emission of carbon dioxide that is driving the rapid rise of global temperatures. The ocean absorbs much of that excess carbon dioxide, and as it does so, the pH of the ocean water declines, meaning it becomes more acidic (just as CO2-laden soda is more acidic than regular water).

As the ocean acidifies, it becomes difficult for shelled organisms such as oysters and clams to build their shells, as well as for fish to breathe. Some of the species that could be most impacted, particularly phytoplankton, sit at the base of the ocean food chain, potentially taking away a key food source for many other species, including some that are most economically valuable, such as salmon and black cod.

The waters off the West Coast of the U.S. are particularly vulnerable to acidification because they feature cold water upwelling from deeper in the ocean. Cold water is better at absorbing CO2 (which also makes acidification in the frigid waters of the Arctic a major concern for marine life there). The cold, upwelling waters also provide abundant nutrients and make the area a rich spot for marine life.

Offshore acidification had been studied before, but with the new study, “we literally took that picture and we moved it all the way to the surf zone,” Chan said.

Multiple institutions joined to install sensors in the coastal waters from Monterey Bay to just north of Newport, Oregon. The sensors monitored conditions for the three years, from 2011 to 2013, and found clear evidence of intense acidification.

Waters fell well below the global average ocean pH of 8.1, with the worst-hit areas measuring 7.4, among the lowest values ever recorded in surface waters.

“The bad news is that we have acidified, compromised water,” Chan said.

But, crucially, “it’s not the same everywhere,” he said. The sensors showed distinct spatial patterns of hot spots and areas where levels were more moderate, and, particularly striking, those areas stayed as hot spots, or relative refuges, “year after year after year.”

Why certain areas have been hit hard and others haven’t wasn’t a focus of the study, but Chan said it likely has to do with the interactions of winds and ocean currents. Some of the sensors from the study are still in place, and Chan is working with citizen scientists in marine reserves in Oregon to better understand local conditions.

He thinks that this same persistent pattern of hot spots and refuges probably isn’t confined to the West Coast. “I think that that’s something that’s going to hold for everywhere in the world,” he said.

Such detailed information is useful for local officials trying to mitigate the impacts of ocean acidification. They can use the maps generated to see where local stressors, such as pollution, might be making conditions worse. They can target the worst-hit areas, while working to ensure that the relative refuges stay that way. Strategies could include limiting local pollution and maintaining healthy kelp beds and sea grasses, which are thought to help mitigate the impacts of acidification.

As atmospheric carbon dioxide levels have risen (in red), the ocean has absorbed some of that CO2 (in green), lowering its pH (in blue). NOAA

Chan was part of a panel of scientists convened by California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia to look at the issue of ocean acidification along the West Coast and whether any mitigation could be done on the local and regional level.

Since the April 2016 release of the panel’s report, two bills have already passed in California to reduce the impacts of ocean acidification and promote its research. A bill to establish an ocean policy council is currently moving its way through Oregon’s government.

The Pacific Northwest has been one of the most proactive regions of the U.S. in dealing with ocean acidification, in part because of an oyster hatchery crisis a decade ago. One hatchery saw an 80 percent decline in oysters because of acidic waters. In response, the industry and regional governments implemented an early warning system so that hatcheries can take measures like treating water to prevent damage to their oysters.

Chan has spoken with oyster farmers in Washington about how they might use the coastal acidification maps his work has generated and what they would do if the area they grow oysters in turned out to be a hot spot. Oysters, like wine, have a specific terroir, or flavor, based on where they’re grown, which would seem to make oyster growers reluctant to relinquish their favored spots.

But their response surprised Chan. They said they’d move.

At a minimum, there should be a steep carbon tax. This could be offset by doubling or tripling the standard deduction. Combine it with a financial transaction tax, high marginal top rates, and treating capital gains the same as income, and you’ve made a real start on global warming while creating an equitable, pro-working class, pro-growth tax system.

And Nero fiddled while Rome burned.

“pro growth tax system”

Real pro growth means broad based prosperity, not neoliberal exploitation. Money for the working class.

If so, then growth is not the word you want, since it has become code for more consumption. This planet has far more human consumption right now that it can handle, this article showing one more example. Perhaps William Gibson or Lambert will come up with a better term.

This article fails to the point of obfuscation because it focuses upon a specific, localized aspect of the problem. Humans can do very well without oysters served on the half shell. They and the planet they inhabit cannot prosper with oceans degraded to the point of becoming biological deserts.

The major threat posed by ocean acidification is its effect upon the bottom of the food chain upon which all oceanic life rests. Everything from giant whales to stationary filter feeders rely upon plankton to provide the base of their food supply. And many species of plankton simply dissolve if the PH falls outside of the range where they can form exoskeletons. 1/4 of all oceanic species rely upon coral reefs as nurseries or habitats, and coral reefs worldwide are well on the way toward extinction.

The problem in a simple flash card: https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/endangered_oceans/pdfs/Infographic_OA.pdf

This is the sort of issue where we need to start thinking of more than just CO2 reductions, we are causing so much damage that only active intervention can work. One possibility is to start mining the mineral Olivine and adding it to soil or to marine sedements. This will both sequester some CO2 and also increase PH.

Needless to say, this sort of intervention is risky and can have all sorts of unintended consequences, even if it works, but we’ve left things too late, there may well be no choice soon.

Olivine……another idea that sounds good on paper, but….

If you’ve ever been around mining, you know that mining uses a huge amount of electricity, and they don’t get it from solar or wind……

The studies I’ve seen build that into the figures – its actually the grinding of the mineral to dust that is most energy intensive, which is why the marine deposition idea sounds good (using waves to do the hard work of breaking down the pebbles).

The reality is that all potential solutions require energy inputs, whether its building windfarms, manufacturing insulation and triple glazed windows or making woodchip or biochar. Its all about the energy balance.

I wish it were that simple…….most of the purveyors of these “pie in the sky” ideas do try to sell you on how simple it all is…..but unfortunately it is not……

I would remind you that the oceans are full of olivine containing basalts (how do you think land forms?) and yet acidification still continues, doesn’t it? So how much olivine are you going to need? Do you think those small (and rare) olivine rich deposits (the kind were you find crystals or pebbles?) are going to do it? Nope, you are going to have to go after huge amounts of basalts and gabbros and grind them up, and then process the ore just to separate and concentrate the small amounts of olivine in them….and that is going to take a huge amount of energy…..

I’ve seen a lot of these “ideas” lately, but unfortunately the only realistic way to reduce ocean acidification is to stop pumping so much CO2 into the atmosphere……

What good news. Thanks PK. They are even thinking of not grinding it down but putting olivine rock on turbulent beaches and let the waves do the work. I think this is very encouraging. And the first thing I thought was, Why can’t a similar technology help to clean the Pacific of all the radiation from Fukushima.

You forgot the sarc tag!

no. i’m really that hopeful.

How audacious.

Beware of letting audacious optimism too favorably frame various schemes for geo-engineering.

There be dragons!

About the oysters – These commercial oysters that have problems are not the native oysters. They are imports from Japan. The native oysters – much smaller in numbers these days (the best places for oysters are taken by the commercial operations) – have not had problems.

There is also this:”The authors draw two conclusions: (1) most non-open ocean sites vary a lot, and (2) and some spots vary so much they reach the “extreme” pH’s forecast for the doomsday future scenarios on a daily (a daily!) basis.”…”Here, we present a compilation of continuous, high-resolution time series of upper ocean pH, collected using autonomous sensors, over a variety of ecosystems ranging from polar to tropical, open-ocean to coastal, kelp forest to coral reef. These observations reveal a continuum of month-long pH variability with standard deviations from 0.004 to 0.277 and ranges spanning 0.024 to 1.430 pH units. The nature of the observed variability was also highly site-dependent, with characteristic diel, semi-diurnal, and stochastic patterns of varying amplitudes. These biome-specific pH signatures disclose current levels of exposure to both high and low dissolved CO2, often demonstrating that resident organisms are already experiencing pH regimes that are not predicted until 2100.” [Gretchen E. Hofmann, Jennifer E. Smith, Kenneth S. Johnson, Uwe Send, Lisa A. Levin, Fiorenza Micheli, Adina Paytan, Nichole N. Price, Brittany Peterson, Yuichiro Takeshita, Paul G. Matson, Elizabeth Derse Crook, Kristy J. Kroeker, Maria Cristina Gambi, Emily B. Rivest, Christina A. Frieder, Pauline C. Yu, Todd R. Martz 2011: Plos One]

There are real man made problems in the ocean today = overfishing – plastic pollution – with which very little is being done – coastal runoff from agriculture. Not to mention that Fukushima is still as it has been doing since it first happened dumping 100s of tons of radiactive water into the Pacific everyday. The currents bring it directly to the West Coast which is evincing numerous dieoffs coincident with the Fukushima meltdowns.

Maybe more informed readers can dispel this simple observation – “When CO2 dissolves in water, we are NOT adding acid to the water. The analog of pouring acid into the water is a false one. What we are doing is adding CO2 to the water, which combines with water molecules to form carbonic acid. This is not the same as adding acid to the water, because the H+ ions we are worried about are already there in the water. We are not adding any more. In fact, one can argue that increasing the CO2 in the water “soaks up” H+ ions into carbonic acid and by doing so shifts the balance so that in fact less calcium carbonate will be removed from shells” So the ocean absorbing CO2 is not the same as experiments involving dumping acid into seawater and observing the effect.

Or this;Matt Ridley: Taking Fears Of Acid Oceans With A Grain of Salt [GWPF] [Wall St Journal]

The central concern is that lower pH will make it harder for corals, clams and other “calcifier” creatures to make calcium carbonate skeletons and shells. Yet this concern also may be overstated. Off Papua New Guinea and the Italian island of Ischia, where natural carbon-dioxide bubbles from volcanic vents make the sea less alkaline, and off the Yucatan, where underwater springs make seawater actually acidic, studies have shown that at least some kinds of calcifiers still thrive—at least as far down as pH 7.8.

In a recent experiment in the Mediterranean, reported in Nature Climate Change, corals and mollusks were transplanted to lower pH sites, where they proved “able to calcify and grow at even faster than normal rates when exposed to the high [carbon-dioxide] levels projected for the next 300 years.” In any case, freshwater mussels thrive in Scottish rivers, where the pH is as low as five.

Human beings have indeed placed marine ecosystems under terrible pressure, but the chief culprits are overfishing and pollution. By comparison, a very slow reduction in the alkalinity of the oceans, well within the range of natural variation, is a modest threat, and it certainly does not merit apocalyptic headlines.

Damming rivers traps sediment, so that delta formation is slowed down (e.g. Mississippi delta) and settlement of the delta along with erosion means critical habitat loss. This can also be seen in many areas with beaches and sand islands where the raw materials to replenish them are trapped behind a dam. That is a key reason why beach replenishment dredging programs are needed.

In some areas with deforestation due to logging and slash & burn for agriculture, the opposite occurs where huge quantities of silt are eroded from the land and silt up critical habitat areas such as estuaries and coral reefs.

Simultaneously, industrial agriculture and suburban lawns are pumping huge amounts of nutrients out into estuaries and deltas, causing massive algae blooms that then reduce oxygen levels (Gulf of Mexico, Lake Erie). Urban sewage can cause similar issues but is more focused around large cities than region wide agricultural and lawn runoff.

These are huge ocean and lake stressors that have nothing to do with climate change and CO2. They can be modified without changing a single thing regarding coal or oil.

Claims:

1) Commercial oysters have problems that don’t bother native oysters.

2) pH levels vary from place to place and from time to time.

“These biome-specific pH signatures disclose current levels of exposure to both high and low dissolved CO2, often demonstrating that resident organisms are already experiencing pH regimes that are not predicted until 2100.”

3) Overfishing and plastic pollution and agricultural pollution are impacting fish.

4) Fukushima meltdowns are not good for fish.

5) “When CO2 dissolves in water, we are NOT adding acid to the water. The analog of pouring acid into the water is a false one. What we are doing is adding CO2 to the water, which combines with water molecules to form carbonic acid. This is not the same as adding acid to the water, because the H+ ions we are worried about are already there in the water. We are not adding any more. In fact, one can argue that increasing the CO2 in the water “soaks up” H+ ions into carbonic acid and by doing so shifts the balance so that in fact less calcium carbonate will be removed from shells” … Huh?????

6) “Off Papua New Guinea and the Italian island of Ischia, … at least some kinds of calcifiers still thrive—at least as far down as pH 7.8.”

7) ” … corals and mollusks were transplanted to lower pH sites, where they proved “able to calcify and grow at even faster than normal rates when exposed to the high [carbon-dioxide] levels projected for the next 300 years.” In any case, freshwater mussels thrive in Scottish rivers, where the pH is as low as five.”

Rather than tussle over every one of this odd combination of claims counter to the post I think #5 is probably at the heart of matters. The chemistry of carbonic acid does not support the claim that adding CO2 to water differs in its effect from adding acid to water. The formation of carbonic acid, H2CO3, when CO2 dissolves in water: CO2 + H2O forms carbonic acid H2CO3. But there are three forms of H2CO3, carbonic acid, when it’s dissolved in water: H2CO3 and HCO3 + H+ and CO3 + 2[H+]. It’s plainly false to assert “adding CO2 to the water, which combines with water molecules to form carbonic acid” is not the same as adding acid to the water “… because the H+ ions we are worried about are already there in the water.” No … the total number of hydrogen atoms, initially bound to oxygen in water, are conserved. But some CO2 dissolved in water reacts with the water to form H2CO3. And the hydrogen ions [H+] and 2[H+] in solution which result are not the same as hydrogen atoms bound to oxygen in the water before reacting with the dissolved CO2.

The rest of the 7 items outlined above are red herrings at best and though I’m tempted I don’t believe they require or deserve further discussion.

“They can be modified without changing a single thing regarding coal or oil.”

And that, I think, is a pretty general view of all things environmental for many on NC. It is false, but momentarily comforting. Rathe like voting for Macron, I should imagine.

Please explain how this was a false statement. Simply stating that it is false is not the same as demonstrating that it is false (something our President apparently has had no reason to learn).

We could completely go to electric cars in this country and still have the same volume of fertilizer runoff and urban sewage destroying estuaries, so the ecological value of those deltas and estuaries would be nearly unchanged despite eliminating a huge source of CO2 to the atmosphere.

I believe it is a fundamental error to focus exclusively on carbon emissions as there are many areas where significant improvements can be made that will give us more resilience. Those are battles that can be won, even with climate change deniers. Focusing on carbon exclusively is the reason why Trump and Congress were able to overturn the stream protection rules as that was part of the “War on Coal” instead of being a battle over a decent environment with significantly less erosion and acidification of surface water.

The article deals with CO2 comprehensively but I wish to mention the radiation risk.

I recall a San Francisco activist group complaining after Fukushima that publication of the weekly analysis of seawater for radiating ions was stopped without explanation.

There was comment at the time that the pacific coastal waters flow round the ocean, up from Japan, across the Aleutians and down the coast of British Columbia, Oregon and California.