By Dani Rodrik, Ford Foundation Professor of International Political Economy, Harvard. Originally published at VoxEU

Populism has been on the rise for quite some time, and it is doubtful that it will be going away. This column argues that the populist backlash to globalisation should not have come as a surprise, in light of economic history and economic theory. While the backlash may have been predictable, however, the specific forms it took were less so, and are related to the forms in which globalisation shocks make themselves felt in society.

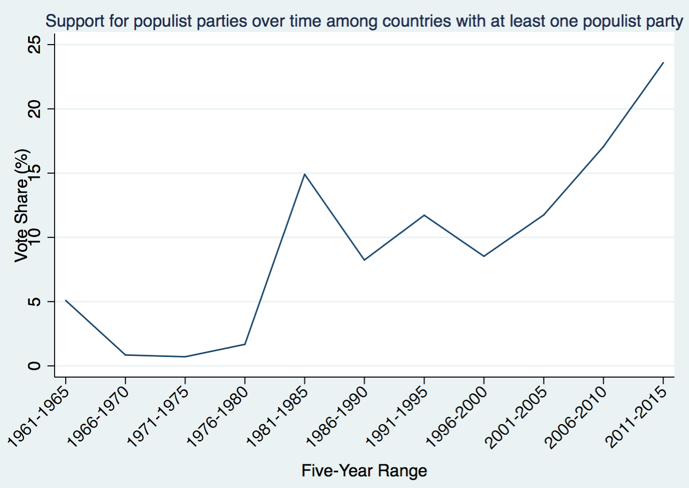

Populism appears to be a recent phenomenon, but it has been on the rise for quite some time (Figure 1). Despite recent setbacks in the polls in the Netherlands and France, it is doubtful that populism will be going away. The world’s economic-political order appears to be at an inflection point, with its future direction hanging very much in balance.

Figure 1 The global rise of populism

Notes: See Rodrik (2017) for sources and methods.

‘Populism’ is a loose label that encompasses a diverse set of movements. The term originates from the late 19th century, when a coalition of farmers, workers, and miners in the US rallied against the Gold Standard and the Northeastern banking and finance establishment. Latin America has a long tradition of populism going back to the 1930s, and exemplified by Peronism. Today populism spans a wide gamut of political movements, including anti-euro and anti-immigrant parties in Europe, Syriza and Podemos in Greece and Spain, Trump’s anti-trade nativism in the US, the economic populism of Chavez in Latin America, and many others in between. What all these share is an anti-establishment orientation, a claim to speak for the people against the elites, opposition to liberal economics and globalisation, and often (but not always) a penchant for authoritarian governance.

The populist backlash may have been a surprise to many, but it really should not have been in light of economic history and economic theory.

Take history first. The first era of globalisation under the Gold Standard produced the first self-conscious populist movement in history, as noted above. In trade, finance, and immigration, political backlash was not late in coming. The decline in world agricultural prices in 1870s and 1880s produced pressure for resumption in import protection. With the exception of Britain, nearly all European countries raised agricultural tariffs towards the end of the 19th century. Immigration limits also began to appear in the late 19th century. The United States Congress passed in 1882 the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act that restricted Chinese immigration specifically. Japanese immigration was restricted in 1907. And the Gold Standard aroused farmers’ ire because it was seen to produce tight credit conditions and a deflationary effect on agricultural prices. In a speech at the Democratic national convention of 1896, the populist firebrand William Jennings Bryan uttered the famous words: “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

To anyone familiar with the basic economics of trade and financial integration, the politically contentious nature of globalisation should not be a surprise. The workhorse models with which international economists work tend to have strong redistributive implications. One of the most remarkable theorems in economics is the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, which generates very sharp distributional implications from opening up to trade. Specifically, in a model with two goods and two factors of production, with full inter-sectoral mobility of the factors, owners of one of the two factors are made necessarily worse off with the opening to trade. The factor which is used intensively in the importable good must experience a decline in its real earnings.

The Stolper-Samuelson theorem assumes very specific conditions. But there is one Stolper-Samuelson-like result that is extremely general, and which can be stated as follows. Under competitive conditions, as long as the importable good(s) continue to be produced at home – that is, ruling out complete specialisation – there is always at least one factor of production that is rendered worse off by the liberalisation of trade. In other words, trade generically produces losers. Redistribution is the flip side of the gains from trade; no pain, no gain.

Economic theory has an additional implication, which is less well recognised. In relative terms, the redistributive effects of liberalisation get larger and tend to swamp the net gains as the trade barriers in question become smaller. The ratio of redistribution to net gains rises as trade liberalisation tackles progressively lower barriers.

The logic is simple. Consider the denominator of this ratio first. It is a standard result in public finance that the efficiency cost of a tax increases with the square of the tax rate. Since an import tariff is a tax on imports, the same convexity applies to tariffs as well. Small tariffs have very small distorting effects; large tariffs have very large negative effects. Correspondingly, the efficiency gains of trade liberalisation become progressively smaller as the barriers get lower. The redistributive effects, on the other hand, are roughly linear with respect to price changes and are invariant, at the margin, to the magnitude of the barriers. Putting these two facts together, we have the result just stated, namely that the losses incurred by adversely affected groups per dollar of efficiency gain are higher the lower the barrier that is removed.

Evidence is in line with these theoretical expectations. For example, in the case of NAFTA, Hakobyan and McLaren (2016) have found very large adverse effects for an “important minority” of US workers, while Caliendo and Parro (2015) estimate that the overall gains to the US economy from the agreement were minute (a “welfare” gain of 0.08%).

In principle, the gains from trade can be redistributed to compensate the losers and ensure no identifiable group is left behind. Trade openness has been greatly facilitated in Europe by the creation of welfare states. But the US, which became a truly open economy relatively late, did not move in the same direction. This may account for why imports from specific trade partners such as China or Mexico are so much more contentious in the US.

Economists understand that trade causes job displacement and income losses for some groups. But they have a harder time making sense of why trade gets picked on so much by populists both on the right and the left. After all, imports are only one source of churn in labour markets, and typically not even the most important source. What is it that renders trade so much more salient politically? Perhaps trade is a convenient scapegoat. But there is another, deeper issue that renders redistribution caused by trade more contentious than other forms of competition or technological change. Sometimes international trade involves types of competition that are ruled out at home because they violate widely held domestic norms or social understandings. When such “blocked exchanges” (Walzer 1983) are enabled through trade they raise difficult questions of distributive justice. What arouses popular opposition is not inequality per se, but perceived unfairness.

Financial globalisation is in principle similar to trade insofar as it generates overall economic benefits. Nevertheless, the economics profession’s current views on financial globalisation can be best described as ambivalent. Most of the scepticism is directed at short-term financial flows, which are associated with financial crises and other excesses. Long-term flows and direct foreign investment in particular are generally still viewed favourably. Direct foreign investment tends to be more stable and growth-promoting. But there is evidence that it has produced shifts in taxation and bargaining power that are adverse to labour.

The boom-and-bust cycle associated with capital inflows has long been familiar to developing nations. Prior to the Global Crisis, there was a presumption that such problems were largely the province of poorer countries. Advanced economies, with their better institutions and regulation, would be insulated from financial crises induced by financial globalisation. It did not quite turn out that way. In the US, the housing bubble, excessive risk-taking, and over-leveraging during the years leading up to the crisis were amplified by capital inflows from the rest of the world. In the Eurozone, financial integration, on a regional scale, played an even larger role. Credit booms fostered by interest-rate convergence would eventually turn into bust and sustained economic collapses in Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Ireland once credit dried up in the immediate aftermath of the crisis in the US.

Financial globalisation appears to have produced adverse distributional impacts within countries as well, in part through its effect on incidence and severity of financial crises. Most noteworthy is the recent analysis by Furceri et al. (2017) that looks at 224 episodes of capital account liberalisation. They find that capital-account liberalisation leads to statistically significant and long-lasting declines in the labour share of income and corresponding increases in the Gini coefficient of income inequality and in the shares of top 1%, 5%, and 10% of income. Further, capital mobility shifts both the tax burden and the burden of economic shocks onto the immobile factor, labour.

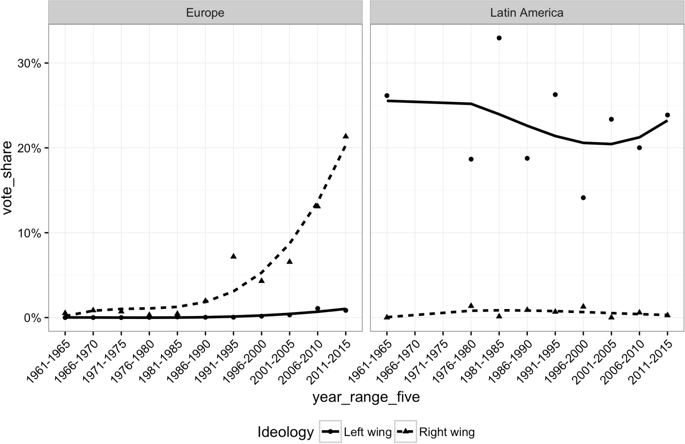

The populist backlash may have been predictable, but the specific form it took was less so. Populism comes in different versions. It is useful to distinguish between left-wing and right-wing variants of populism, which differ with respect to the societal cleavages that populist politicians highlight and render salient. The US progressive movement and most Latin American populism took a left-wing form. Donald Trump and European populism today represent, with some instructive exceptions, the right-wing variant (Figure 2). What accounts for the emergence of right-wing versus left-wing variants of opposition to globalization?

Figure 2 Contrasting patterns of populism in Europe and Latin America

Notes: See Rodrik (2017) for sources and methods.

I suggest that these different reactions are related to the forms in which globalisation shocks make themselves felt in society (Rodrik 2017). It is easier for populist politicians to mobilise along ethno-national/cultural cleavages when the globalisation shock becomes salient in the form of immigration and refugees. That is largely the story of advanced countries in Europe. On the other hand, it is easier to mobilise along income/social class lines when the globalisation shock takes the form mainly of trade, finance, and foreign investment. That in turn is the case with southern Europe and Latin America. The US, where arguably both types of shocks have become highly salient recently, has produced populists of both stripes (Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump).

It is important to distinguish between the demand and supply sides of the rise in populism. The economic anxiety and distributional struggles exacerbated by globalisation generate a base for populism, but do not necessarily determine its political orientation. The relative salience of available cleavages and the narratives provided by populist leaders are what provides direction and content to the grievances. Overlooking this distinction can obscure the respective roles of economic and cultural factors in driving populist politics.

Finally, it is important to emphasise that globalization has not been the only force at play — nor necessarily even the most important one. Changes in technology, rise of winner-take-all markets, erosion of labour market protections, and decline of norms restricting pay differentials all have played their part. These developments are not entirely independent from globalisation, insofar as they both fostered globalization and were reinforced by it. But neither can they be reduced to it. Nevertheless, economic history and economic theory both give us strong reasons to believe that advanced stages of globalisation are prone to populist backlash.

See original post for references

An interesting post.

One question he does not address is why the opposition to globalisation has had its most obvious consequences in two countries:- the US and the UK with Trump and Brexit respectively. I suggest that the fact that these two countries are arguably the most unequal in the advanced world has something to do with this. Also, on many measures I believe these two countries appear to be the most ‘damaged’ societies in the advanced world – levels of relationship breakdown, teenage crime, drug use, teenage pregnancies etc. I doubt this is a coincidence. For me the lessons are obvious – ensure the benefits of increased trade are distributed among all affected, not just some; act to prevent excessive inequality; nurture people so that their lives are happier.

re: “ensure the benefits of increased trade are distributed among all affected”

Note that for the recent TPP, industry executives and senior government officials were well represented for the drafting of the agreement, labor and environmental groups were not.

There simply may be no mechanism to “ensure the benefits are distributed among all affected” in the USA political climate as those benefits are grabbed by favored groups, who don’t want to re-distribute them later.

Some USA politicians argue for passing flawed legislation while suggesting they will fix it later, as I remember California Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein stating when she voted for Bush Jr’s Medicare Part D (“buy elderly votes for Republicans”).

It has been about 15 years, and I don’t remember any reform efforts on Medicare Part D from Di-Fi.

Legislation should be approached with the anticipated inequality problems solved FIRST when wealthy and powerful interests are only anticipating increased wealth via “free trade”. Instead, the political process gifts first to the wealthy and powerful first and adopts a “we’ll fix it later” attitude for those harmed. And the same process occurs, the wealthy/powerful subsequently strongly resist sharing their newly acquired “free trade” wealth increment with the free trade losers..

If the USA adopted a “fix inequality first” requirement, one wonders if these free trade bills would get much purchase with the elite.

Forced Free Trade was intended to be destructive to American society, and it was . . . exactly as intended.

Millions of jobs were abolished here and shipped to foreign countries used as economic aggression platforms against America. So of course American society became damaged as the American economy became mass-jobicided. On purpose. With malice aforethought.

NAFTA Bill Clinton lit the fuse to the bomb which finally exploded under his lovely wife Hillary in 2016.

The big problem I find in this analysis is that it completely forgets how different countries use fiscal/financial policies to play merchantilistic games under globalization.

Yves, thanks for posting this from Dani Rodrik — whose clear thinking is always worthwhile. It’s an excellent, succinct post. Still, one ‘ouch’: “Redistribution is the flip side of the gains from trade; no pain, no gain.”

This is dehumanizing glibness that we cannot afford. The pain spreads like wildfire. It burns down houses, savings, jobs, communities, bridges, roads, health and health care, education, food systems, air, water, the ‘real’ economy, civility, shared values — in short everything for billions of human beings — all while sickening, isolating and killing.

The gain? Yes, as you so often point out, cui bono? But, really it goes beyond even that question. It requires asking, “Is this gain so obscene to arguably be no gain at all because its price for those who cannot have too many homes and yachts and so forth is the loss of humanity?

Consider, for example, Mitch McConnell. He cannot reasonably be considered human. At all. And, before the trolls create any gifs for the Teenager-In-Chief, one could say the same — or almost the same — for any number of flexians who denominate themselves D or R (e.g. Jamie Gorelick).

No pain, no gain? Fine for getting into better shape or choosing to get better at some discipline.

It’s an abominable abstraction, though, for describing phenomena now so far along toward planet-o-cide.

“Populism” seems to me to be a pejorative term used to deligitimize the grievances of the economically disenfranchised and dismiss them derision. Another categorization that I find less than apt, outmoded and a misnomer is the phrase “advanced economies”, especially given that level of industrialization and gdp per capita are the key metrics used to arrive at these classifications. Globalization has shifted most industrial activity away from countries that invested in rapid industrialization post WW2 to countries with large pools of readily exploitable labour while gdp per capita numbers include sections of the population with no direct participation in creating economic output (and the growth of these marginalized sections is trending ever upward). Meanwhile the financial benefits of growing gdp numbers gush ever upwards to the financial-political elites instead of “trickling downwards” as we are told they should, inequality grows unabated, stress related diseases eat away at the bodies of otherwise young men and women etc. I’m not sure any of these dynamics, which describe perfectly what is happening in many so called advanced economies, are the mark of societies that should describe themselves as “advanced”…

Sorry, but the original populist movement in the US called themselves the Populists or the Populist Party. Being popular is good. You are the one who is assigning a pejorative tone to it.

Populism is widely used in the mainstrem media, and even in the so called alternative media, as a really perjorative term. That is what he means (I would say).

This. At least here, in post-communist central Europe, Populism is a code word for “Unserious” proposals to benefit the many, that are supposed to cause loss of jobs, loss of competitiveness , slower GDP growth, our capitalist gods getting angry and what-have-you. The obvious implication being that supporting these proposal means that you are an idiot too stupid to understand that There is no Alternative(tm).

“What all these share is an anti-establishment orientation, a claim to speak for the people against the elites, opposition to liberal economics and globalisation, and often (but not always) a penchant for authoritarian governance.”

On the other hand:

“What all these share is an establishment orientation, a claim to speak for the elites against the people, support for liberal economics and globalisation, and always a penchant for authoritarian governance.”

You nailed it. Let me know when we get our Constitution back!

“Financial globalisation appears to have produced adverse distributional impacts within countries as well, in part through its effect on incidence and severity of financial crises. Most noteworthy is the recent analysis by Furceri et al. (2017) that looks at 224 episodes of capital account liberalisation. They find that capital-account liberalisation leads to statistically significant and long-lasting declines in the labour share of income and corresponding increases in the Gini coefficient of income inequality and in the shares of top 1%, 5%, and 10% of income. Further, capital mobility shifts both the tax burden and the burden of economic shocks onto the immobile factor, labour.”

So, translated, Rodrick is saying that the free flow of money across borders, while people are confined within these artificial constraints, results in all the riches flowing to the fat cats and all the taxes, famines, wars, droughts, floods and other natural disasters being dumped upon the peasants.

The Lakota, roaming the grassy plains of the North American mid-continent, glorified their ‘fat cats,’ the hunters who brought back the bison which provided food, shelter and clothing to the people. And the rule was that the spoils of the hunt were shared unequally; the old, women and children got the choice high calorie fatty parts. The more that a hunter gave away, the more he was revered.

The Lakota, after some decades of interaction with the European invaders, bestowed on them a disparaging soubriquet: wasi’chu. It means ‘fat-taker;’ someone who is greedy, taking all the best parts for himself and leaving nothing for the people.

“So, translated, Rodrick is saying that the free flow of money across borders, while people are confined within these artificial constraints…..”

Nailed it!!

That’s something that has always bothered me……it’s great for the propagandists to acclaim globalization but they never get into the nitty-gritty of the “immobility” of the general populations who have been crushed by the lost jobs, homes, families, lives…….there should be a murderous outrage against this kind of globalized exploitation and the consequent sufferings. Oh, but I forgot! It’s all about the money……that is supposed to give incentive to those who are left behind to “recoup”, “regroup” and in today’s age develop some kind of “app” to make up for all those losses…..In the capitalist economies globalization is/was inevitable; the outcome is easy to observe…..and suffer under.

they never get into the nitty-gritty of the “immobility” of the general populations who have been crushed by the lost jobs, homes, families, lives

That’s a feature, not a bug. Notice that big corporations are all in favor of globalization except when it comes to things like labor law. Then, somehow, local is better.

And not-so-artificial borders. As I’ve been saying for well over 30 years, since Reagan disingenuously told people, “Vote with your feet,” it’s rather easier to do that when your “feet” consist of a few key strokes to move your electronic money anywhere in the world you like and rather more difficult when your “feet” involve the uprooting and relocation of your family. Not to mention that the job you’re relocating to has been thoroughly crapified by free trade. And doubly not reaching the problem of having to be completely retrained because The People Who Matter have decided to scrap your industry and ship it to China or Mexico (or worst of all the Northern Marianas, where retailers get sweatshop prices while still getting to claim the products are Made in USA).

“The economic anxiety and distributional struggles exacerbated by globalization generate a base for populism, but do not necessarily determine its political orientation. The relative salience of available cleavages and the narratives provided by populist leaders are what provides direction and content to the grievances. ”

Excellent and interesting point. Which political party presents itself as a believable tool for redress affects the direction populism will take, making itself available as supply to the existing populist demand. That should provide for 100 years of political science research.

Anonymous2 : “For me the lessons are obvious – ensure the benefits of increased trade are distributed among all affected, not just some; act to prevent excessive inequality; nurture people so that their lives are happier.”

Seems so simply, right ?

It ought to be but sadly I fear our politicians are bought. I am unsure I have the solution . In the past when things got really bad I suspect people ended up with a major war before these sorts of problems could be addressed. I doubt that is going to be a solution this time.

This piece was a lengthy run-on Econ 101 bollocks. Not only does the writer dismiss debt/interest and the effects of rentier banking, but they come off as very simplistic. Reads like some sheltered preppy attempt at explaining populism

Well said.

Yep, Rodrik has been writing about these things for decades and has a remarkable talent for never actually getting anywhere. He’s particularly enamored by the neoliberal shiny toy of “skills”, as if predation, looting, and fraud simply don’t exist.

And yet, in the profession, he is one of the least objectionable.

That’s an intriguing thought to ponder. In some ways, I absolutely agree. He’s much better than most.

And yet, the cumulative effect of accepting least bad options is why we are at where we are at. In some ways, intellectuals like Rodrik strike me as precisely what is wrong with our system, conveniently aloof to how their framing and advocacy entrenches inequality rather than critiques the power structure.

This is a prime example of what is wrong with professional economic thinking. First, note that Rodrik is nominally on our side: socially progressive, conscious of the increasingly frightful cost of enviro externalities, etc. But like almost all economists, Rodrik is ignoring the political part of political economy. Historically, humanity has developed two organizational forms to select and steer toward preferred economic destinies: governments of nation states, and corporations. Only nation states provide the mass of people any form and extent of political participation in determining their own destiny. The failure of corporations to provide political participation can probably be recited my almost all readers of NC. Indeed, a key problem of the past few decades is that corp.s have increasingly marginalized the role of nation states and mass political participation. The liberalization of trade has come, I would argue, with a huge political cost no economist has reckoned yet. Instead, economists are whining about the reaction to this political cost without facing up to the political cost itself. Or even accept its legitimacy.

Second, there are massive negative effects of trade liberalization that economists simply refuse to look at. Arbitration of environmental and worker safety laws and regulations is one. Another is the aftereffects of the economic dislocations Rodrik alludes to. One is the increasing constriction of government budgets. These in turn have caused a scaling back of science R&D which I believe will have huge but incalculable negative effects in coming years. How do you measure the cost of failing to find a cure for a disease? Or failing to develop technologies to reverse climate change? Or just to double the charge duration of electric batteries under load? As I have argued elsewhere, the most important economic activity a society engages in us the development and diffusion of new science and technology.

Intellectually poisoned by his social environment perhaps. The biggest problems with this piece were its sweeping generalizations about unquantified socio-political trends. The things that academic economists are least trained in; the things they speak about in passing without much thought.

I.e. Descriptions of political ‘populism’ that lumps Peronists, 19th century U.S. prairie populists, Trump, and Sanders all into one neat category. Because, social movements driven by immiseration of the common man are interchangeable…… like paper cups at a fast food restaurant.

Agree with much of what you comment….I believe that the conditions you describe are conveniently dismissed by the pro economists as: “Externalities” LOL!! They seem to dump everything that doesn’t correlate to their dream of “Free Markets”, “Globalization”, etc….into that category….you gotta love ’em!!

Rodrik is also wrong about the historical origins of agrarian populism in USA. It was not trade, but the oligopoly power of railroads, farm equipment makers, and banks that were the original grievances of the Grangers, Farmers Alliances after the Civil War.

In fact, the best historian of USA agrarian populism, Lawrence Goodwyn, argued that it was exactly the populists’ reluctant alliance with Byran in the 1896 election that destroyed the populist movement. It was not so much an issue of the gold standard, as it was “hard money” vs “soft money” : gold AND silver vs the populists’ preference for greenbacks, and currency and credit issued by US Treasury instead of the eastern banks. A rough analogy is that Byran was the Hillary Clinton of his day, with the voters not given any way to vote against the interests of Goldman Sachs or the House of Morgan.

Honestly I would say Bryan is more an unwitting Bernie Sanders than a Hillary Clinton. But the effect was essentially the same.

“the oligopoly power of railroads, farm equipment makers, and banks that were the original grievances “

That power was expressed in total control of the Congress and Presidential office. Then, as now, the 80-90% of the voters had neither R or D party that represented their economic, property, and safety interests. Given the same economic circumstances, if one party truly pushed for ameliorating regulations or programs the populist movement would be unnecessary. Yes, Bryan was allowed to run (and he had a large following) and to speak at the Dem convention, much like Bernie today. The “Bourbon Democrats” kept firm control of the party and downed Jennings’ programs just as the neolib Dem estab today keep control of the party out of the hands of progressives.

an aside: among many things, the progressives pushed for good government (ending cronyism), trust busting, and honest trade, i.e not selling unfit tinned and bottled food as wholesome food. Today, we could use an “honest contracts and dealings” act to regulate the theft committed by what the banks call “honest contract enforcement”, complete with forges documents. (Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle (1906) about the meatpacking industry. What would he make of today’s mortgage industry, or insurance industry, for example.)

For an author and article so interested in international trade, I’m fascinated by the lack of evidence or argumentation that trade is the problem. The real issue being described here is excessive inequality delivered through authoritarianism, not international trade. The intra-city divergence between a hospital administrator and a home health aid is a much bigger problem in the US than trade across national borders. The empire abroad and the police state at home is a much bigger problem than competition from China or Mexico. Etc. Blaming international trade for domestic policies (and opposition to them) is just simple misdirection and xenophobia, nothing more.

I take exception to most of Prof. Rodrik’s post, which is filled with factual and/or logical inaccuracies.

“Populism appears to be a recent phenomenon, but it has been on the rise for quite some time (Figure 1).”

Wrong. Pretending that a historical generic is somehow new… Populism has been around since at least the time of Jesus… or William Wallace… or the American Revolution… or FDR.

“What all these share is an anti-establishment orientation, a claim to speak for the people against the elites, opposition to liberal economics and globalisation, and often (but not always) a penchant for authoritarian governance.”

Wrong. Creating a straw man through overgeneralization. Just because one country’s “populism” appears to have taken on a certain color, does not mean the current populist movement in another part of the world will be the same. The only essential characteristics of populism are the anti-establishment orientation and seeking policies that will redress an imbalance in which some elites have aggrandized themselves unjustly at the expense of the rest of the people. The rest of the items in the list above are straw men in a generalization. Rise of authoritarian (non-democratic) governance after a populist uprising implies the rise of a new elite and would be a failure, a derailing of the populist movement – not a characteristic of it.

“Correspondingly, the efficiency gains of trade liberalisation become progressively smaller as the barriers get lower.”

If, in fact, we were seeing lower trade barriers, and this was driving populism, this whole line of reasoning might have some value. But as it is, well over half the US economy is either loaded with barriers, subject to monopolistic pricing, or has not seen any “trade liberalization”. Pharmaceuticals, despite being commodities, have no common global price the way, say, oil does. Oil hasn’t had lowered barriers, though, and thus doesn’t count in favor of the argument either. When China, Japan and Europe drop their import barriers, and all of them plus the U.S. get serious about antitrust enforcement, there might be a case to be made…

“It is useful to distinguish between left-wing and right-wing variants of populism”

Actually it isn’t. The salient characteristic of populism is favoring the people vs. the establishment. The whole left/right dichotomy is a creation of the establishment, used to divide the public and PREVENT an effective populist backlash. As Gore Vidal astutely pointed out decades ago, there is really only one party in the U.S. – the Property Party – and the Ds and Rs are just two heads of the same hydra. Especially in the past 10 years or so.

About the only thing the author gets right is the admission that certain economic policies unjustly create pain among many groups of people, leading to popular retribution. But that’s not insightful, especially since he fails to address the issue quantitatively and identify WHICH policies have created the bulk of the pain. For instance, was more damage done by globalization, or by the multi-trillion-$ fleecing of the U.S. middle class by the bankers and federal reserve during the recent housing bubble and aftermath? What about the more recent ongoing fleecing of the government and the people by the healthcare cartels, at about $1.5-2 trillion/year in the U.S.?

This is only the top of a long list…

““It is useful to distinguish between left-wing and right-wing variants of populism”

Actually it isn’t. The salient characteristic of populism is favoring the people vs. the establishment. The whole left/right dichotomy is a creation of the establishment, used to divide the public and PREVENT an effective populist backlash.”

Yeah, sorry no. Just because two groups are both anti-establishment doesn’t mean they can’t have wildly different opinions on important topics such as abortion, gay rights, immigration, death penalty, religious freedom and religious equality, climate change …

Which is the primary worldview setting for the neoreactionary right in America. Everything is a question of whether or not ones income was “fairly earned.” So you get government employees and union members voting for politicians who’ve practically declared war against those voters’ class, but vote for them anyway because they set their arguments in a mode of fairness morality: You can vote for the party of hard workers, or the party of handouts to the lazy. Which is why China keeps getting depicted as a currency manipulator and exploiter of free trade agreements. Economic rivals can only succeed via “cheating,” not being industrious like the US.

That describes a number of my relatives and their friends. They are union members and government employees yet hold hard right-wing views and are always complaining about lazy moochers living on welfare. I ask them why they love the Republicans so much when this same party demonizes union members and public employees as overpaid and lazy and the usual answer is that Republicans are talking about some other unions or other government employees, usually teachers.

I suspect that the people in my anecdote hate public school teachers and their unions because they are often female and non-white or teach in areas with a lot of minority children. I see this a lot with white guys in traditional masculine industrial unions. They sometimes look down on unions in fields that have many female and non-white members, teachers being the best example I can think of.

No, no they don’t.