Dear patient readers,

I’ve had a reversal with my eyesight. I seemed to be pretty much over my eye injury and resulting cornea edema. However, today my vision in my dominant eye has gotten blurry enough that I am again finding it hard to read, even when increasing the font size in my browser. Note the doctors seem to think there is nothing to do but let the eye recover on its own. So please forgive the lack of posts by me.

Note a point made in passing towards the end of this post, which strikes me as important: diversified investors don’t have incentives to discipline monopolists. If the monied types spread their chips out widely enough, they’ll benefit from whoever comes out on top.

By Silvia Merler, an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel and previously, an Economic Analyst in DG Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission. Originally published at Bruegel

Plenty of recent research has highlighted a rise in concentration in the US economy, across different sectors. Economists are now wondering to what extent this is attributable to a shift in the antitrust enforcement philosophy. We review contributions to this debate.

In a new paper in the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s series on antitrust policy, John E. Kwoka of Northeastern University documents the rise in concentration and examines the evidence for one possible explanation: the change in merger enforcement policy at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

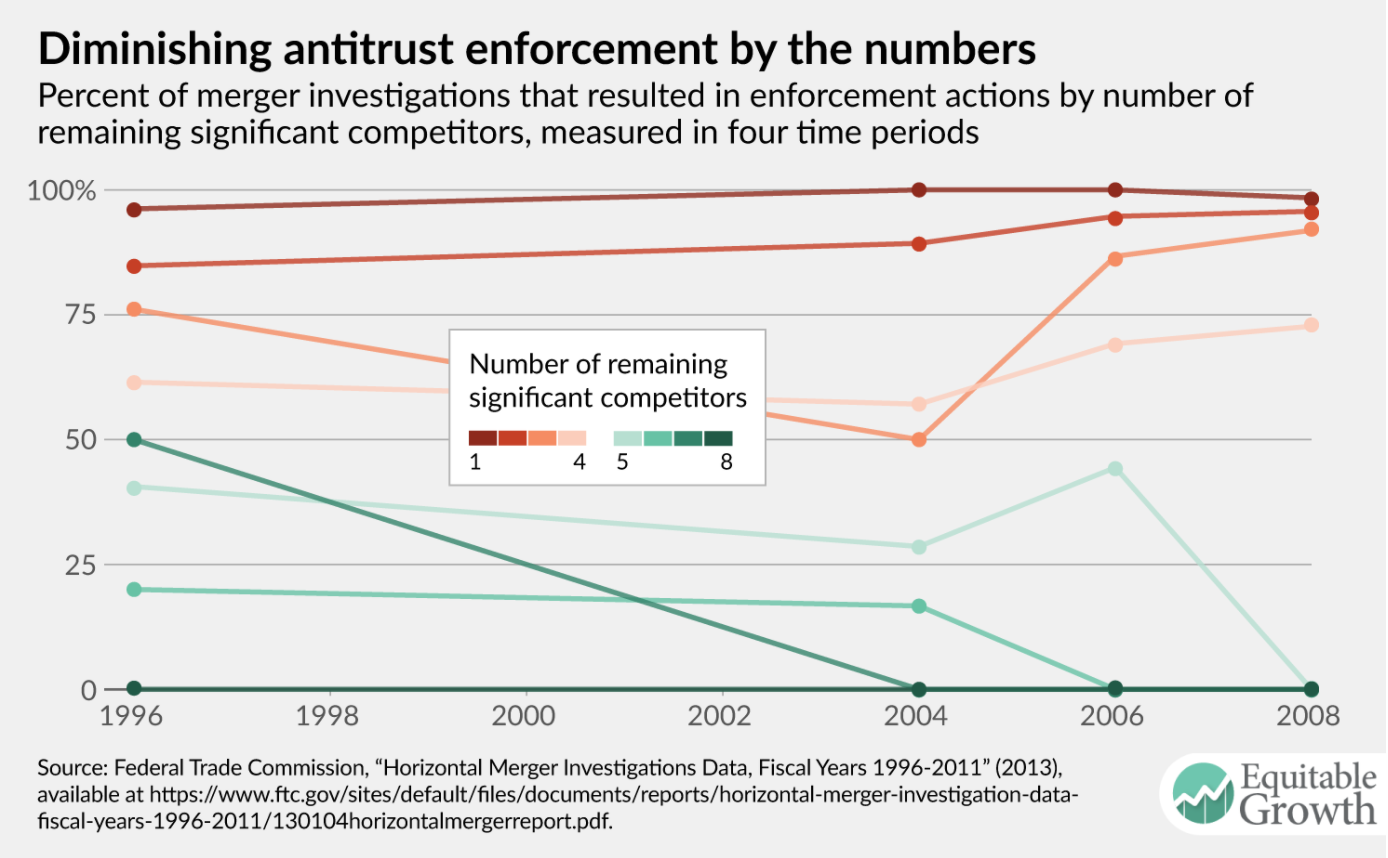

Examining FTC merger enforcement data from 1996 through 2011, Kwoka finds that merger enforcement narrowed its focus to mergers at the very highest levels of concentration and adopted a more permissive stance. His examination of the data reveals that (i) enforcement rates for mergers that would result in four or fewer significant competitors slightly increased from 1996 through 2011, but (ii) enforcement for mergers that would result in more than four remaining significant competitors literally ceased after 2007 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Kwoka

Kwoka argues that the reason for this is to be found in a changing antitrust policy’s presumptions about the competitive consequences of increases in concentration. Over the past 50 years, that presumption shifted from the viewpoint that even modest increases in concentration would result in above-competitive prices and profits, to one in which it was believed that tougher merger standards sacrificed cost efficiencies, which presumably would be passed onto consumers. While antitrust policy has moderated from this original “Chicago school” view, the FTC enforcement data from 1996 through 2011 nonetheless demonstrate that there has continued to be a shift away from merger enforcement actions outside the most concentrated markets.

Some previous research by Kwoka himself had tried to establish the level of concentration at which anti-competitive outcomes become nearly certain. He found that in mergers that resulted in six or fewer significant competitors, prices rose in nearly 95 percent of cases. For mergers with a greater number of remaining competitors, the percentage that were anti-competitive fell off steadily, suggesting that a presumption against mergers in the range of six or five, competitors would make few errors. It is therefore notable that enforcement policy has shifted to permissiveness precisely in this range of five to seven significant competitors.

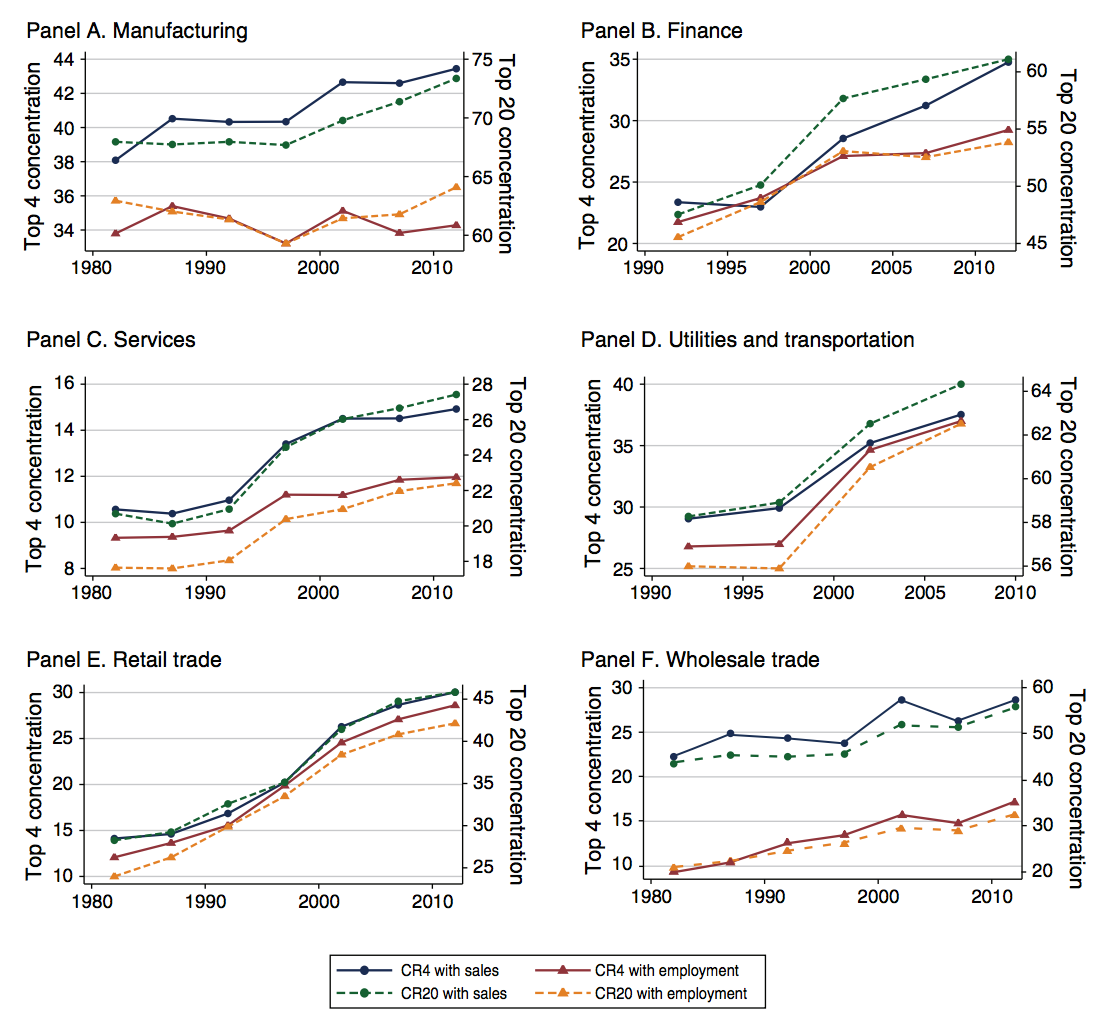

Autor, Dorn, Katz, Patterson and Van Reenen look at concentration changes throughout the U.S. economy from 1982 to 2012. They develop three different measures of concentration for 676 industries in six broad sectors, both for purely U.S.-based firms and after controlling for imports, and find a remarkably consistent upward trend in concentration in each sector. Four-firm concentration, i.e. the share of industry revenues controlled by the largest four firms, rose from 38 percent to 43 percent in manufacturing, from 24 percent to 35 percent in finance, from 11 percent to 15 percent in utilities, from 29 percent to 37 percent in retail trade, and from 22 percent to 28 percent in wholesale trade (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Source: Autor et al.

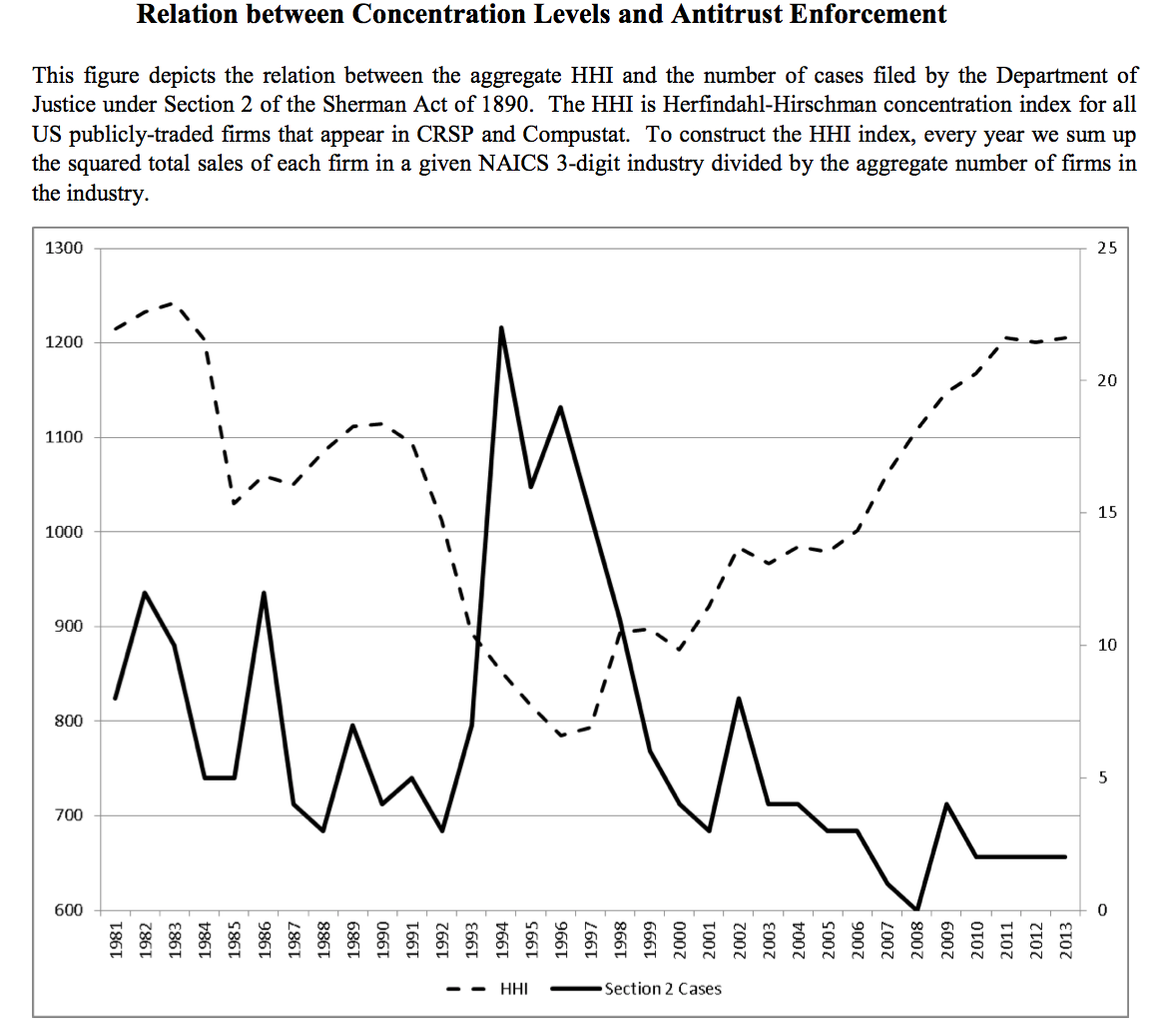

Grullon, Larkin and Michaely look at stock market data on publicly traded firms aggregated to their respective industries and reports on changes in concentration measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, over the past 40 years. They find that more than 75% of US industries have experienced an increase in concentration levels over the last two decades. Firms in industries with the largest increases in product market concentration have enjoyed higher profit margins, positive abnormal stock returns, and more profitable M&A deals, suggesting that market power is becoming an important source of value. They argues that lax enforcement of antitrust regulations and increasing technological barriers to entry appear to be important factors behind this trend (Figure 3). Overall, our findings suggest that the nature of US product markets has undergone a structural shift that has weakened competition.

Figure 3

Source: Grullon et al.

Khan and Vaheesan look at the role of monopoly and oligopoly power in the context of economic inequality, arguing that there is reason to believe the pervasive market power in the economy has contributed to the high level of economic inequality in the United States today. Given the general affluence of shareholders and executives relative to consumers – as well as the power dynamics within large companies – we can expect market power to have significant regressive distributional effects. Case studies of anticompetitive practices and non-competitive market structures in several key industries illustrate how large firms have come to dominate the U.S. economy. Additionally, monopolistic and oligopolistic companies translate their economic power into political influence, often successfully pushing for laws and regulations that further entrench their position and transfer wealth upwards. They argue that the prevalence of market power in the economy today was not inevitable, but is the product of an intellectual and political shift in the 1980s that dramatically reoriented and narrowed the goals of antitrust law.

Jonathan Baker argues that the surprising conjunction of the exercise of market power with well-established antitrust norms, precedents, and enforcement institutions is the central paradox of U.S. competition policy today. Baker argues that this is due to insufficient deterrence of anticompetitive coordinated conduct and insufficient deterrence of anticompetitive mergers between rivals as well as of anticompetitive exclusion. Additional reasons for concerns are the fact that market power is durable, the increased equity ownership of rival firms by diversified financial investors, the rise of oligopolies and of dominant information technology platforms and the decline in US economic dynamism in the past few decades. He also argues that governmental restraints on competition appear to have grown. These include more extensive occupational licensing, growth in the scope of what may be patented, along with an excessive number of patents improperly granted as a result of inadequate review of patent applications.

Yves writes:

For example, Berkshire Hathaway has investments in each of the Big Four U.S. airlines

(American, Delta, Southwest and United) in the $2-3 billion range.

Who yah going to fly with, Spirit?

Yves, sorry to hear about your other eye – give it as much rest as it needs.

This is kind of meta, but I have a blog, and when something like this is posted, and I want to comment on it, I am wondering the proper citation.

What I would typically do, (for example) is to provide a link to Bruegel at the top of the page, since it was originally published there, and then have the note (with link to this), “H/t Naked Capitalism,” as the last line.

Is this proper linkback etiquette, or should I just provide the link to Bruegel, or just the link to NC?

See here.

About those eyes: When I was waiting for the insurance merry-go-round to allow me back into coverage, my cataracts continued to thicken. The “Blank Your Monitor” plugin for Firefox helped immensely. I still use it all the time, even with new plastic lenses in my eyeballs. Over in Chrome, “Deluminate” accomplishes the goal differently.

In the Digital Age, the U.S. needs an entirely new standard for antitrust enforcement. Up to now, the yardstick has been consumer prices: it’s OK to have a monopoly as long as you don’t use it to jack up prices. But Google and Facebook are free, so by definition they can’t be doing anything wrong (even though they are obviously using their monopoly power to harm consumers).

This explains it brilliantly.

Efficiency isn’t the be-all and end-all that economists like to think it is – just ask and engineer – and redundancy is something that needs to be considered as well.

You could probably make a jet with only one engine but there’s a very good reason they are generally constructed with four.

Same should go for an economy.

Well, we could argue that by hoovering up all the social media companies and therefore advertising that FB and Google are driving up the price of advertising, which can filter down and impact all pricing. What if for example FB had to compete with social networks like Instagram and What’s App instead of using stock and free cash to kill competitive social networks?

Yves, sorry to hear of your eye troubles, get better soon!!!!

” Over the past 50 years, that presumption shifted from the viewpoint that even modest increases in concentration would result in above-competitive prices and profits, to one in which it was believed that tougher merger standards sacrificed cost efficiencies, which presumably would be passed onto consumers. ”

An interesting aspect of focusing solely on prices is it ignores value. NC commentariate often remark on the “crapification” of goods and services. Where there were once many media owners and outlets, they competed for market share based on quality of product or focusing on a particular outlook, now there are less than a handful.

per Wikipedia:

“As of 2015, Comcast Corporation is the largest media conglomerate in the US, with The Walt Disney Company, News Corp and Time Warner ranking second, third and fourth respectively.[7]

….

“As of February 2017, AT&T and Time Warner are in talks to merge into one super-conglomerate creating the largest mass media and entertainment company in the United States.[citation needed] The deal is said to be “imminent” after the FCC declined to review the deal stating it’s “out of our wheelhouse”.[8][not in citation given] Many industry experts believe the merger would violate anti-trust laws.[8][”

Perhaps a cable bill is priced lower (or higher) than it would be without near monopoly. Leaving price aside, what is the quality of the product delivered? When all the media reports the same stories from the same viewpoint and with the same conclusion (see 2016 election campaigns, for example), one could argue that price should not be the only consideration for anti-monopoly enforcement. Informal collusion to degrade the general product is a form of price gouging. Crapification is an unmeasured cost to the customer.

Good point.

If all the companies involved in a sector agrees to lower their quality standards but keep prices the same, the customer loses while the companies gets to pad their margins.

And while a hardened libertarian will claim that one should then vote with ones wallet and forgo the sector completely, doing so will be hard if community assumes that one own such a product or service.

I’m not a big fan of the recent discourse that portrays some very large domestic companies as simply ‘monopolies’ that should be managed by questioning future acquisitions and possibly breaking them up. This portrayal ignores how their size was attained, and why this dominance is maintained. Many of these firms have for years relied on legal protections not available to their competitors to ensure their competitive advantage. These protections include ignoring existing laws, profiting from illegal businesses where profits exceed fines, and profiting from exclusive U.S. government subsidies not available to competitors. Legal protections are effectively rents. They do nothing to advance society. When opportunities for rent collection become systemic, economic rents crowd out risky innovation because returns for economic rents are lower, but guaranteed ( risk free ). Purchasing legal protections ( rents ) drains societies capabilities, efficiencies, and resources, while Innovation advances societies capabilities, efficiencies, and resources. Simply labeling a company a monopoly and limiting future acquisitions does not address any of this.

I assume you think that some of the existing giants should be broken up (and I agree). Do you have some recommendations as to which corporations are most in need of being split apart? Amazon.com and Walmart come to mind, as well as some of the computer and internet giants.

Amazon and Walmart both profit from different types of protections ( rents ).

Walmart’s protection is federal, state, and local government subsidies of poverty wages for its more than 1 million U.S. employees. I think only 1/3 of its employees earn more than $25,000 per year, and their definition of full-time is 34 hours a week ( 15% fewer hours resulting in proportionately less pay than 40 hours per week ). The result is taxpayers supplementing these poverty wages through Food Stamps, Medicaid, EIC Tax Credits, Day Care, and Subsidized Housing.

Amazon’s protection is a federal government subsidy of their cost of shipping. E-Commerce is unquestionably more convenient that brick and mortar shopping, but it is only cheaper when the aggregate cost of shipping is below the aggregate cost of brick and mortar maintenance. To guarantee this the U.S. Postal Service has a confidential agreement with Amazon to deliver its packages at what has been conservatively estimated at half what they are charged by UPS and FedEx. Our government eats the cost of this below market service and Amazon reaps the profits.

These are only two examples of how protections help build monopolies. I think ending these protections should take precedence before breaking them up.

The Walmart subsidies are indirect: they directly assist millions of people, which indirectly assists Walmart. Before any of those subsidies can be removed, some major reforms are needed, such as a significantly higher minimum wage, and Medicare-for-All.

Amazon is different. Any special agreement that the Postal Service has with Amazon should be nullified right away. Amazon already benefitted from not charging most customers sales tax in the company’s early years of operation.

I think monopolies (and the largest oligopolies and oligopsonies) need to be broken up first, but that is very unlikely in the near future, as both the Democrats and the Republicans are heavily beholden to the oligarchs who own and control the giant corporations. This includes the cable TV and internet giants — they need to be broken up as well.

That’s great and all but Kwoka seems to be reinventing the wheel a bit with this research.

It always amazes me that economists, even the ones I like, get paid to do research like this.

Everbody knows that the dice are loaded.

This research is really important, actually. It counters the dominant economic theory about antitrust enforcement, and couldn’t possibly come at a better time. The only way to counter the religion that is the Chicago School is with FACTS. Kwoka did a laborious deep dive into the FTC’s own data and has proof that the noticeable change in enforcement had measurable effects.

We need research like this to prove that what the Chicago School is selling is snake oil. The current acting chair of the FTC went to good ole’ George Mason Law School, a hotbed of conservative economics of exactly this type. With republicans taking back the reins at the DOJ and the FTC, it is important that this research be produced now to keep things from swinging too far to the right, meaning towards very lax “business friendly” enforcement.

On the subject of lax enforcement, I still vividly remember an NPR news report early one morning (working yet another !00+ hour week of unpaid overtime) in early 1986, in which the following numbers were cited: in the first five years of the Reagan administration, there were 27,000 applications for mergers, acquisitions and takeovers of all kinds. As of January, 2006, only two had been denied, and only six were still under review.

The pattern has become de rigueur from that time onward. No administration since has paid more than lip service to existing anti-trust law. For the very largest part, regardless of who’s running the Executive Branch, anti-trust law has effectively been ignored, and I suspect that’s particularly true in favor of Silicon Valley firms, the “innovators,” who have amassed so much cash that it’s a trivial exercise for them to buy out smaller competitors and new product developers, to the point where the business plan of most developers is centered around getting bought out.

Oops, sorry. “As of January, 2006,…” should have read, “As of January, 1986,…”

Lost in my own ozone….