Fall colors fade in U.S. west as aspen trees die Reuters

The Cupcake Bubble Daniel Gross, Slate

The Last Temptation of Risk Barry Eichengreen, National Interest (hat tip Brad DeLong)

How Many Rabbits Are Left In The Hat? Michael Shedlock

The Battle of Jericho Kevin Drum (hat tip Megan McArdle)

Lobbyists Feel the Pinch As Downturn Hits K Street Washington Post

The Wait for Financial Reform Alan Blinder, New York Times

The Real Story of “Zombie Banks” Washington’s Blog

U.S. Recovery Leaving Workers Jobless May Spur Company Profits Bloomberg. DoctoRx deemed this to be a joint Orwell/Pangloss watch item.

Friedman Economics: Is Fed chairman Ben Bernanke a follower of John Maynard Keynes or Milton Friedman? Penn Bullock, Reason Magazine

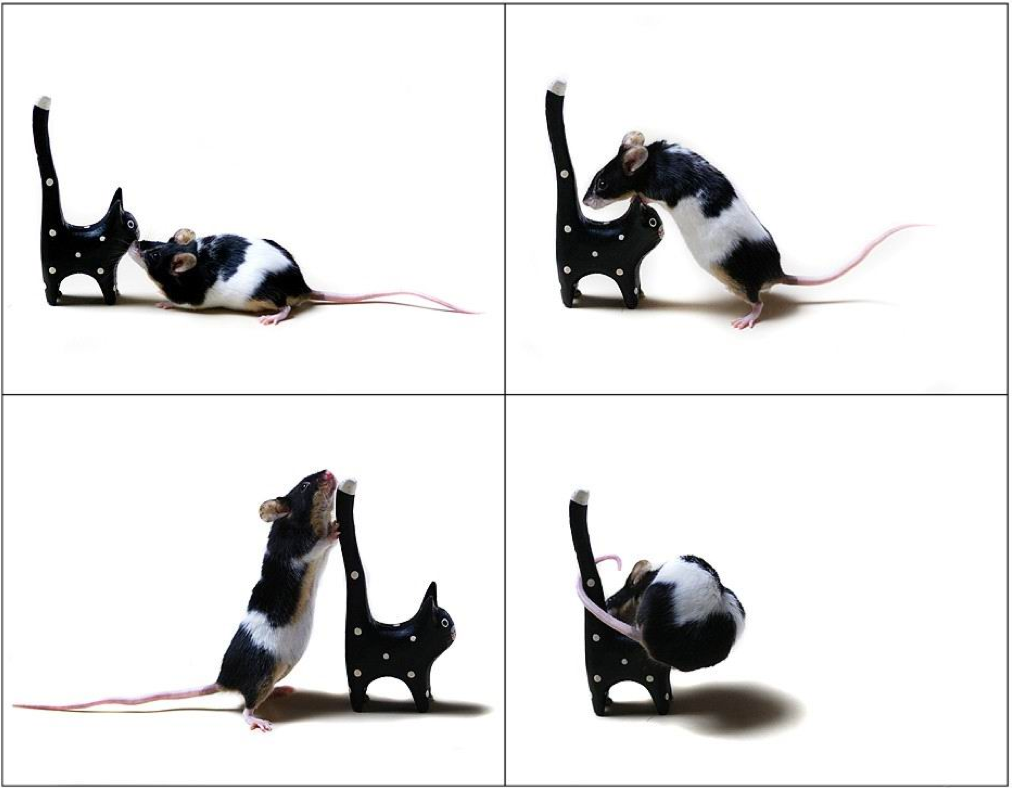

Antidote du jour:

Re: battle for Jericho…pure Clockwork Orange stuff. Police used to be recruited primarily from local sources, not inter-state, plus the war footing ideology of its US vs THEM mentality can only have one outcome. Hay its only a job with better than average pay and some nice perks, why risk your life or limb when you feel threatened. In criminal law the victim only has to *feel* threated to justify many actions, including law enforcement officers….shez.

Skippy…Your honour he raised his finger in a threating manner so I in an attempt to protect myself and the citizans…shot him.

I’m viewing on Safari.. the image is half cut off

@”Friedman Economics” by Penn Bullock

Absolutely superb!

For those who enjoyed the Bullock essay, the following essay about Friedman by Paul Krugman might also be of interest:

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/19857

Bullock’s concluding sentence–“For two libertarian champions of free markets and limited government, this legacy has the ring of a world-historic irony.”–says volumes about the entire discipline of economics. Such ironies become inevitable when a discipline becomes so theoretical that it completely divorces itself from any this-world reality.

Fortunately for the people of the United States, the theorists have always been kept in check by men of action or of experience. As Reinhold Niebuhr put it: “Any modern community which establishes a tolerable justice is the beneficiary of the ironic triumph of the wisdom of common sense over the foolishness of its wise men.”

Hannah Arendt provides a more elaborate explanation of America’s extraordinary stroke of good luck deriving from its colonial experience. The American revoutionaries

“knew of the enormous power potential that arises when men ‘mutually pledge to each other their lives, their Fortunes and the sacred Honour.’ ”

“This was the experience that guided the men of the Revolution; it had taught not only them but the people who had delegated and ‘so betrusted’ them, how to establish and found public bodies, and as such it was without parallel in any other part of the world. The same, however, is by no means true of their reason, or rather reasoning, of which Dickinson rightly feared that it might mislead them. Their reason, indeed, both in style and content was formed by the Age of Enlightenment as it had spread to both sides of the Atlantic; they argued in the same terms as their French or English colleagues, and even their disagrements were by and large still discussed within the framework of commonly shared references and concepts… This lack of conceptual clarity and precision with respect to existing realities and experiences has been the curse of Western history ever since, in the aftermath of the Periclean Age, the men of action and the men of thought parted company and thinking began to emancipate itself altogether from reality, and especially from political factuality and experience.”

Theory-based dogmas like libertarianism thus ALWAYS deteriorate into these situations where there is layer upon layer of irony and hypocrisy. Niebuhr provides another example of libertarian hypocrisy:

“Thus, for instance, a laissez faire economic theory is maintained in an industrial era through the ignorant belief that the general welfare is best served by placing the least possible political restraints upon economic activity…”

“When economic power desires to be left alone it uses the philosophy of laissez faire to discourage political restraint upon economic freedom. When it wants to make use of the police power of the state to subdue rebellions and discontent in the ranks of its helots, it justifies the use of political coercion and the resulting suppression of liberties by insisting that peace is more precious than freedom and that its only desire is social peace.”

And Greg Grandin provides yet another example of the hypocrisy inherent in libertariansim, where its mandarins

(continued)

And Greg Grandin provides yet another example of libertarian hypocrisy, where its mandarins (Friedman and Friedrich von Hayek, perhaps the best known of the Friedmanettes) throw their support behind a murderous military dictatorship and demand a country be brought to its knees on the altar of fiscal austerity, while back at home preach freedom and democracy and argue money should be showered down from helicopters:

http://www.counterpunch.org/grandin11172006.html

Shedlock or rather the article he links to on the August unemployment numbers is an excellent read. Even on their face, they show an economy that is not turning around, but if you look more deeply into them, break them down, look at past trends and future consequences, they are much more worrisome.

The Blinder op-ed on the other hand is a waste of pixels. Blinder from Princeton (and who was at the Fed) thinks the Fed and Bernanke from Princeton (and, of course, the chair of the Fed) should be the systemic risk regulator. Who could have predicted? But mainly he dances around the issue of why there is no push for regulation. The reason, not given, but the most cogent is that the Obama Administration and its economics team don’t really want any and in any case such a push would most likely have to be led by Geithner and can anyone see him effectively leading anything?

The article on Bernanke and Friedman is good too. It seems very odd how terms get thrown around. Bernanke has never been Keynesian. Most of Obama’s policies, including a sizeable chunk of his “stimulus”, weren’t either. Bernanke always struck me as more neo-Keynesian, a bizarre appellation (another would be the misnamed “neoliberalism”)since it represents a philosophy which reversed much of Keynes. But the connection to Friedman is as the article points out fundamental to understanding Bernanke’s viewpoint.

“The real problem, though, is that the cupcakes are essentially reactionary.”

Speak truth to power, brother! lol!

Shedlock’s piece on rabbits hit the nail on the head when it referred to Geither’s heaping praise on himself.

I’m not sure precisely when it is in anyone’s experience with Geithner that they realize that he is simply the most loathsome maggot. Perhaps its when they sense that he doesn’t look at a questioner straight on. But add to that foreknowledge of his tax escapades and the impression is almost certainly clinched. And such as this leads us!

@Hugh,

Keynes, Friedman, for or me it’s Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum. Both were consummate polemicists that had one objective, and that was to exculpate the princes of Wall Street for their sins.

Compare these two statements, this one from the Bullock piece:

“Friedman and Schwartz, however, denied that speculation had ever posed a problem, or that there had even been a credit bubble in the 1920s. In their narrative, a paranoiac Federal Reserve had needlessly constricted the money supply and thereby crashed an otherwise prosperous economy.”

And this one from a synopsis of Keynes’ 1936 book “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money” where Keynes discusses the causes of the Great Depression:

“A peculiar state of affairs, indeed: a tragedy without a villain. No one can blame society for saving, when saving is so apparently a private virtue. It is equally impossible to chastise businessmen for not investing when no one would be so happy to comply as they–if they saw a reasonable chance for success. The difficulty is no longer a moral one–a question of justice, exploitation, or even human foolishness. It is a technical difficulty, almost a mechanical fault”

–Robert Heilbroner, “The Worldly Philosophers”

(Ha! Ha! I’ll bet Marx and Veblen were rolling over in their graves!)

Then place the two above statements within this framework provided by Reinhold Niebuhr in “Moral Man and Immoral Society”:

“The physical sciences gained their freedom when they overcame the traditionalism based on ignorance, but the traditionalism which the social sciences face is based upon the economic interest of the dominant social classes who are trying to maintain their special privileges in society. Nor can the difference between the very character of social and physical sciences be overlooked. Complete rational objectivity in a social situation is impossible. The very social scientists who are so anxious to offer our generation counsels of salvation and are disappointed that an ignorant and slothful people are so slow to accept their wisdom, betray middle-class prejudices in almost everything they write. Since reason is always, to some degree, the servant of interest in a social situation, social injustice cannot be resolved by moral and rational suasion alone, as the educator and social scientist believes. Conflict is inevitable, and in this conflict power must be challenged by power. That fact is not recognized by most of the educators, and only very grudgingly admitted by most of the social scientists.”

According to Hannah Arendt, the concept that power must be met with power comes down to us, vis-à-vis the Founding Fathers, from Montesquieu:

“For Montesquieu’s discovery actually concerned the nature of power, and this discovery stands in so flagrant a contradiction to all conventional notions on this matter that it has almost been forgotten, despite the fact that the foundation of the republic in America was largely inspired by it. The discovery, contained in one sentence, spells out the forgotten principle underlying the whole structure of separated powers: that only ‘power arrests power’… Power, contrary to what we are inclined to think, cannot be checked, at least not reliably, by laws…and in a conflict between law and power it is seldom the law which will emerge as victor.”

What Keynes appears to be touching on there is the paradox of thrift. It is an important point. What makes sense for an individual can have devastating consequences in the aggregate if many individuals make the same decision. That is what he means that there is no villain. Good individual decisions can have overall disastrous results.

Schwartz is making a very different point, and one I do not agree with, about preeminent role of monetary policy in causing and deepening the Great Depression. That analysis does miss the importance of fraud and speculation, and it also misses the importance of directed federal stimulus to achieve the very Keynesian goal of creating through government spending demand at both the individual level and in the aggregate.

Friedman I find contradictory but the current crisis has proved his ideas on a monetary approach, like Schwartz’s, and also Bernanke’s to be wrong. They have been tried and they don’t work for what many of us would see as obvious reasons, i.e. pushing on a string.

On Blinder.

Momentum for reform is decreasing and will continue to do so, even if the real economy remains depressed. No politician will ever be re-elected on a basis of “successfully having reformed financial regulation”. Politicians will want to move on, or rather, they will have to find new issues that sell.

From this general rule, there may be exceptions, of course. Strong leaders (i.e. of the kind that manage to see beyond the next Gallup & election)exist and we will see afterwards if there were any around this time.

With this in mind, I believe it was wrong to reappoint Bernanke. He will inevitably spend too much focus on “rectifying” the heritage from his first tenure, for instance by blocking sensible reforms that would risk tarnishing the past (further).

As I have written on these pages before, the coming year will involve a change (or re-confirmation) of leadership in key European states and at EU level that largely will determine whether the EU will seize the opportunity to undertake thorough reform. It could go both ways, really.

Furthermore, The European Parliament is sharpening its knives on the proposed new EU Hedge Fund legislation. Remember that the EC Commission put forward its proposal in the spring and that the propsal immediately was critisized by the Industy as being a death warrant. Now, the European Parliament (co-legislator with the EU Council of Ministers) has appointed its rapporteur (draftsperson) who apparently thinks that the proposal does not go far enough………….

Euractiv: http://www.euractiv.com/en/financial-services/ep-hedge-fund-rapporteur-go-ahead-regulation/article-185120

This will be interesting to watch.

@Hugh,

What Keynes and Friedman have in common, along with all the other Keynesians, Friedmanites, libertarians, Austrians, classicists, neo-Keynesians and neoclassicists, is that they either ignore, as was the case with Keynes, or outright eschew, as was the case with Friedman:

•Regulation

•Punishment, and

•Accountability.

This pattern appears over and over again with the adherents of these doctrines, espescially when dealing with elites, so a motif of double standards also emerges, as Arendt and Niebuhr are quick to point out.

Don’t get me wrong. I have no desire to unduly demonize Keynes, as entirely too many do. But on the other hand, I don’t believe in ultimate goodies and baddies either.

“For at heart he was a conservative–long an admirer of Edmund Burke and of the tradition of limited government for which Burke stood,” Heilbroner describes Keynes. He was also a “traditionalist,” Heilbroner adds, who “liked to think that greatness ran in families…. And it would be a grave error in judgment to place this man, whose aim was to secure capitalism, in the camp of those who wanted to submerge it.”

The portrait Heilbroner paints of Keynes is that of a person with a prodigal intellect that towers over that of the typical corporate or Wall Street CEO’s (Into this latter category I would put Friedman.). And Keynes was fully cognizant of this. “I want to manage a railway or organize a Trust or at least swindle the investing public,” he wrote to his lover Strachey; “it is so easy and fascinating to master the principles of these things.” Heilbroner also lauds Keynes as an “economist of extraordinary insight,” an ability also lacking in the average CEO, who typically sees only about three inches in front of his nose.

And what Keynes could foresee were the dark clouds closing in not only upon the princes of Wall Street, but upon the entire United States. As Heilbroner explains:

“The voice of Marx rang louder than it ever had rung in the past; many pointed to the unemployed as prima-facie evidence that Marx was right… And there was the still more chilling voice that never wearied of pointing out that Hitler and Mussolini knew what to do with their unemployed.”

So Heilbroner asserts that Keynes’ policies were “born of desperation rather than design.” When “The General Theory” came out in 1936, “what it offered was not so much a new and radical program as a defense of a course of action that was already being applied.”

It is not difficult to see that, given Keynes’ objectives, it would not have done to make an issue of Wall Street’s crimes and excesses of the 20s, nor to call for accountability or punishment for those crimes.

But what of Keynes’ theories, formulated in the crucible of social and political unrest? For, as Heilbroner explains, “the pump-priming program never brought the results that the planners had hoped for.” Heilbroner, in typical left-wing fashion, marks this up to the fact that “the program of government spending was never carried out to the full extent that would have been necessary to bring the economy up to full employment” and the fact that neither “Keynes nor the government spenders had taken into account that the beneficiaries of the new medicine might consider it worse than the disease.”

But I think there’s a third explanation, and that is that these policies never really were designed to repair the economy, but to alleviate social unrest and preserve as much of the status quo as possible.

downsouth – wrt regulation, justice (my preference is to call first for fair trials rather than punishment) and accountability what do you think of post keynesian (and related) economics? i only this past year started reading about this stuff, so please forgive my ignorance, but my impression is that while most keynesian and neo keynesian economists ignore these issues, that is not the case for post keynesians. certainly at this year’s minsky conference at levy there was lots of talk of corruption and crime.

for this, and other reasons, i’ve become quite intrigued by some of the various threads of post keynesian thinking. but again, very much a newbie to all this.