By Tom Adams, an attorney and former monoline executive, and Yves Smith

Despite extensive credit crisis post mortems, many of the widely accepted explanations of what happened are at odds with facts on the ground. These superficial explanations are hard to dislodge because they tally with widely held beliefs about how the real estate and securitization market operate. The waters have been muddied even more by self-serving PR from various market participants.

The consensus reality of the credit crisis appears to be: it was the result of a complex combination of factors, no one can be blamed all that much (save maybe greedy borrowers and complicit rating agencies) and almost no one saw it coming.

We’ve argued that many of the arguments that support that view are myths. In particular, the more we have dug into the CDO market, the more we are convinced that it was central to the crisis. Furthermore, we believe that this market did not operate on an arm’s length basis, that many of the practices that were widespread in the industry amounted to collusion.

Collusion and resulting price distortions serve as the most likely explanations for behaviors that are consistently glossed over in the consensus accounts of the crisis. By early 2006, many mortgage market participants felt that the housing market was overheated and unsustainable. Many felt that mortgage rates should be higher, but despite interest rate tightening by the Fed, mortgage rates were not increasing. Even more distressing, credit spreads remained narrow despite widespread concerns that mortgage risk was increasing and deals were weakening.

Many economists and academics described this as a conundrum at the time and tried to come up with theories to explain it, none of which were terribly satisfying. None of them looked at a more likely culprit – the securitization market and, specifically, the CDO market.

CDOs distorted the mortgage market because they undermined the normal processes for pricing risky assets. For subprime debt, demand for the lower rated tranches had served to constrain market growth. If investors started to shun the BBB to AA rated tranches of subprime mortgage bonds, dealers were not willing to retain them, no new deals would be sold, and the market would need to find better quality mortgages or grind to a halt. But CDOs were the dumping ground for these tranches. A 1990s version of mortgage-related CDOs proved ultimately to be a Ponzi scheme (unsold risky CDO tranches were rolled into new CDOs), but even then, that CDO market imploded early enough that the damage was comparatively minor.

This time, the CDO market distortions were more significant and wide-ranging. In particular:

1. Demand for CDOs came not from long investors, who would be concerned about credit losses, but primarily from (a) short investors who wanted to bet aggressively against the housing market and needed a tool to allow them to do so without disclosing their real intentions (b) investment banks who created the CDOs so they could generate fees and bonuses by putting the CDO bonds in their trading portfolios (negative basis trades) and off balance sheet vehicles (SIVs) without regard to risk and (c) correlation traders who were indifferent to credit risk

2. The normal mechanisms for pricing risk were upended because of manipulation of the demand for mortgage and CDO bonds by a consortium of banks and CDO managers who masked the real appetite for the bonds and fabricated pricing for the bonds

3. By creating the illusion of demand for the mortgage and CDO bonds, the CDO managers and arranging banks operated under a well disguised conspiracy that allowed a massive housing bubble to be created which only exploded when the shorts became impatient for realizing their gains.

If traditional cash investors and insurers were avoiding the mortgage securities market, who was driving the yields and spreads lower? Many industry participants agreed that the “CDO bid” was distorting the market.

The mechanism was the CDO managers, who assembled the assets for cash or hybrid deals (ones like Magnetar’s that used a combination of mortgage bond tranches and credit default swaps). They were effectively extensions of investment banks, dependent on substantial credit lines from them. Perhaps more important, it appears that many of the larger CDO managers bought much, perhaps all, of the AA to BBB tranches of entire subprime mortgage bond issues to be placed into CDOs. Having a single affiliated party take down the riskiest layers of subprime deals means that normal arm’s length pricing was not operating, and the profit potential of CDO issuance, rather than investor demand, was driving the market.

Consider this series of interconnected transactions:

A “sponsor” indicates an interest in creating a CDO to an investment bank. In combination, the sponsor and the bank would select the CDO manager who would buy the mortgage bonds for the CDO at start up and oversee the portfolio after closing. The sponsor would typically provide the CDO manager with an investment objective and find a manager that could achieve these aims.

Since the CDO deals were typically over a billion dollars, the CDO manager didn’t usually have the capital to purchase the mortgage bonds. As a result, the investment bank for the deal would offer the manager a line of credit to use to purchase the bonds that the manager selected. When the CDO closed, the CDO would repay the line of credit.

The bank for the CDO would not offer the line of credit to a thinly capitalized CDO manager casually. They were sure to get an attractive rate of interest plus a security interest in the bonds being financed to protect them in case the CDO manager ran into trouble. In addition, the CDO manager would work hard to find investors in the CDO to pay of the loan from the investment bank.

Many CDO managers were repeat issuers and many had a fairly systematic approach to how they covered the market. For instance, in a particular period, a CDO manager might be responsible for a mezzanine deal and a high grade deal or two. This would mean that the CDO manager had multiple lines of credit active

This execution strategy meant that the CDO manager had significant capital at its disposal for the purpose of buying mortgage bonds. Normally, the process of bidding on newly issued mortgage bonds while trying to meet the eligibility criteria of the proposed CDO transaction can be timing consuming and arduous for the CDO manager. The clever ones with more influence and access to generously termed lines of credit, could use their capital to tremendous advantage. Rather than face the competition of multiple bidders on a particular bond of a new mortgage deal, the CDO manager, armed with multiple upcoming deals and lines of credit, could offer to buy the entire stack of subordinated bonds that the issuer was bringing to market: BB all the way up to AA. This would be very attractive to the issuer, since it made it easier to get his deal sold. It was attractive to the CDO manager, since they could slot the bonds into both their mezzanine deal and their high grade deal at the same time, saving them a considerable amount of work. In addition, it could be very attractive for the bank on the mortgage transaction, particularly if they were the same bank that was issuing the CDO. A bank that knew it would be able to sell its mortgage deal and supply bonds to its CDO deal at the same time would take comfort that it was not terribly exposed to market risk.

One additional feature that some CDO managers might employ is to have a line of credit established for an upcoming CDO squared. A CDO-squared is made up of other CDO bonds, rather than MBS bonds. Putting aside how ridiculous the concept sounds now, this type of deal served a tremendous importance at back in 2006 and 2007. Since the riskier tranches of a CDO were more expensive to the issuers and harder to place, a CDO manager who knew that he had a home for these slices of his upcoming mezzanine or high grade CDO could certainly sleep easier. If managed properly, a CDO manager working with a friendly bank could pre-place the all of the sub bonds for a number of mortgage deals into their mezzanine and high grade deals and also pre-place all of the sub bonds from their mezzanine and high grade deals into a CDO squared transaction.

This example illustrates that pricing was often not based on market demand. Is there any real price discovery if one buyer (the CDO manager) is snapping up all of the risky tranches from a mortgage deal, and the bank on the mortgage deal is the same bank on the CDOs where the bonds will end up? Similarly, if all the risky tranches of a CDO were all pre-placed into another CDO, did anyone even bid on them? And since all of these pieces fit so nicely together, wouldn’t getting competitive bids really have been rather inconvenient?

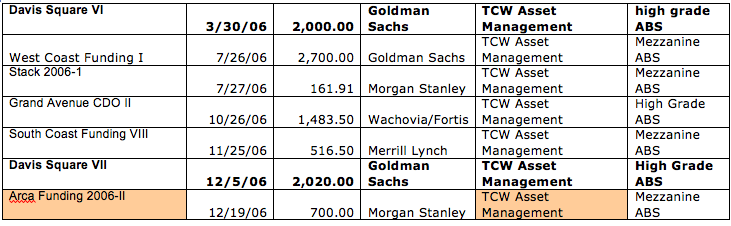

Consider the role that a company like TCW played in the market. TCW was the biggest CDO manager in the ABS CDO market. In 2006, TCW acted as manager on about $9.5 billion worth of CDOs over 7 transactions.

The deals have an interesting pattern – alternating between high grade ($5.5 billion) and mezzanine ($3.4 billion) and across four banks, Goldman, Merrill, Wachovia and Morgan Stanley. The high grade deals included not just A and AA MBS bonds but also similarly rated bonds from other CDOs, including potential the mezzanine and high grade deals managed by TCW during this period.

During this same time 2006, those four bankers owned or acquired subprime lenders who typically securitized most of their originated loans. By rotating among the lenders owned by these banks, TCW could achieve decent diversity in their CDOs without ever having to pursue other lenders for their bonds. While they certainly mixed the bonds of other lenders into the mix to achieve better diversity scores from Moody’s (and lower rating agency cost of issuance, TCW may have offered to take all, or nearly all, of the mortgage bonds issued by the acquired lenders of Merrill Lynch, Wachovia, Morgan Stanley and Citigroup when they brought a subprime or Alt A mortgage deal or perhaps even the occasional deals where the banks had offered the bonds of third party mortgage lenders. If so, it’s likely the offer was received well.

Consider the systemic impact. Lower costs on for the CDO translated into lower, more aggressive bids for the mortgage bonds, which translated into lower mortgage rates – all of which were potentially being set between just 4 or 5 traders

But the risky tranches represented only a relatively small portion of the mortgage or CDO transactions. What happened to the biggest portion of the transactions – the senior (AAA) bonds? The bond insurers insured a decent amount of the market in 2006 (about a third), but even the many of the insured bonds needed a buyer and the uninsured senior bonds still needed a home. As we learned last week when Citigroup testified at the FCIC, Citigroup were big buyers of their own CDOs. Just like with the mezzanine and high mortgage deal, it was probably much more convenient for bank who was selling the senior CDO bonds, to convince management to acquire the bonds themselves rather than try to sell them in a messy, time consuming bid process. Similarly, Yves discussed in ECONNED that Eurobanks frequently retained AAA tranches because Basel II rules gave them considerable latitude in how much (as in how little) capital to charge against them.

As a result, from the top of the structure – the senior bonds of a high grade or mezzanine CDO, all the way down through the mortgage bonds and into the price of the mortgage loans – third party assessments of the risk and rewards of the loan appear to have been limited to non-existent.

The result was that riskier and riskier loans were being originated at effectively lower costs for issuers with little outside feedback. In one big happy family among the mortgage issuers, CDO managers and CDO investors, there would have been little motivation to worry about increasing risk or wider spreads. They were all keen to keep the great fee machine rolling.

Finally, if you throw the shorts into the equation, you complete the picture. Hedge funds who wanted to short subprime were pushing for more and more CDS on MBS, which led to the creation of more CDOs, which in turn, bought more cash and synthetic MBS bonds, helping to keep spreads low. The tight spreads on the mortgage deals created a great buying opportunity for the shorts, who were getting to bid on what we now know were extremely risky loans at bargain basement prices. Once the risks in the mortgage loans began to emerge, spreads on the bonds finally started to widen, sometime in mid 2007. By then it was too late – the deals were already created. Since the bonds had never really been distributed very widely and sat with highly leveraged firms that could not take much in the way of losses, the result was systemic risk and financial crisis.

Your hypothesis that the fee stream fueled the CDO flow is consistent with what I observed and completes the fee narrative in my mind. Traders would point to “foreign demand” and “CDO demand” for the deal volumes and tight spreads when describing the subprime market prior to the meltdown. What I did not realize at the time was that large proportion of subprime exposure sold overseas did not come from the original subprime securitizations but instead from the more profitable repackaged CDO execution.

What is not often discussed is that the dealer-owned originators and servicers had more to do with the degradation in lending standards after 2004 (no doc, negative amortization, option arms, etc.,) than is commonly recognized. The non-depository, non-dealer issuers could not provide enough supply for the CDO fee machine, so the dealers bought and built the platform capacity themselves. If memory serves, Lehman had Aurora and LongBeach, Merrill purchased National City’s subprime unit First Franklin at the real estate peak in ’06 (an eerie parallel to the First Union/Wachovia purchase of the Money Store at the top of the previous subprime cycle), and let’s not forget the Wachovia purchase of World Savings option arms portfolio business. Moreover, the acquiring entities had more capital to deploy than independent subprime originators tethered to their warehouse lines.

Thanks for the insight, the picture becomes clearer and clearer with time.

Thank yo for the posting. It is difficult to wade through some of this but when I get done the same question keeps coming to my mind. Why is there no one in jail for these crimes against humanity? Will there ever be?

Tom & Yves,

I forgot add Bear to my list of dealers that sped up the decline of lending standards. They had a subprime mortgage and servicing company called EMC. It is interesting that Merrill, Lehman, Bear and Wachovia all perished; perhaps the layered fee stream and the lack of market pricing discipline you overrode all risk management considerations.

Thank you Clyde. Mortgage servicers are indeed integral to CDOs. Look at CDO prospectuses and see which servicers are involved, taking note of their parent companies. The entire CDO collateral selection process is ripe for investigation. Are specific securities chosen on the basis of known servicer complicity, “collusion and manipulation”? Not surprising, all servicers to underlying securities in the ABACUS 2007-AC1 deal have been charged with servicing fraud in individual civil suits, class actions or Federal regulatory meaasures with two of the most notorious ABACUS servicers involved in FTC settlements.

EMC Mortgage Corp. – formerly Bear Stearns subsidiary, now JPMC – http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2008/09/emc.shtm

Select Portfolio Servicing – Credit Suisse subsidiary http://www.ftc.gov/fairbanks

Every CDO prospectus I’ve read contains the following boilerplate risk disclosure language, repeated many times over throughout the offering circular.

“CREDIT RISK ARISES FROM losses due to defaults by the borrowers in the underlying collateral or the issuer’s or SERVICER’S FAILURE TO PERFORM.”

How does that legal theory go? . . . if the conflicts are disclosed, they are excused?

Michael, you bring up an interesting disclosure that I’ve noticed as well – specifically in some of Goldman’s docs.

Interestingly, while recognizing the risk of servicing failures – including the risks inherent in “Transfer” of servicing rights – they nonetheless structured many of these transactions with a list of servicers to begin with. Then it is well-known that the servicers immediately began transferring loans between themselves.

Here’s why this point is important:

It used to be that SERVICING INCOME was the real raison d’être for mortgage lenders – NOT the origination income.

Once that emphasis shifted – away from servicing to a total reliance on origination income – you have a guaranteed recipe for disaster. The lenders abandoned an old model which encouraged responsible lending decisions in order to sustain longer-term profitability, and instead adopted a strategy entirely reliant on short-term profits.

It was an unsustainable model, and destined to blow up.

I think that’s why many of these deals were structured with multiple servicers to begin with: so they could quickly start transferring servicing rights in a deliberate effort to create chaos and confusion. They wanted those loans to default – and they muddied the waters to make it more difficult for anyone to lay blame on one particular lender or servicer.

servicing income is an interesting point: when the market is functioning, servicing portfolios run off quickly via refinancing and amortization. once a servicer amasses a large portfolio, it has keep running faster and faster (originating more and more loans) just to keep up with the amortization. this happened to countrywide in spades.

also, in a subprime servicing portfolio, as the portfolio ages, it gets more and more expensive to service, because the good borrowers leave and the bad borrowers, in need of extensive “credit counseling” and foreclosure actions, remain. not a formula for success.

Lenders used to enforce very rigid “seasoning” rules for refinancing: they wouldn’t even consider rewriting a loan that was less than 12 months old.

Further, equity take-outs were extremely difficult – if not IMPOSSIBLE – and appreciation was pretty much ignored by underwriters if it wasn’t supported dollar-per-dollar by improvements made to the property. In other words, they wouldn’t cash-out equity to the homeowner if it resulted strictly from appreciation – especially rapid appreciation.

All these factors reduced the amount of turnover that lenders would experience. I seem to recall back in the 1980’s that a prepayment period of about 7 years was average.

“you cited”

Cogent,plausible explanation of the securities shennigans that logically lays out the implicit fraud and short-sighted avarice, in more ways than one, that have wreaked such societal havoc with lavish immunity to the pathological few

Probably, yes. After all, the aim is to make money, not perform some sort of public service.

“After all, the aim is to make money, not perform some sort of public service.” — said the prostitute, spreading her legs for crack money!

Unbelievably great article! Thank you for this. I don’t understand it well enough yet, but I’m getting there with your help.

William Black cited a book called “Bankruptcy: Looting for Profit” written back in 1993. In this paper it describes how looters (investment banks/CDO managers, whoever) intentionally and purposely look for people who will NOT be able to fulfill their contracts.

They hand out mortgages to people who shouldn’t be getting them, crank up the mortgage system (knowing full well that it will take quite a long time before it all falls apart), make a ton of money all the way up, but when it breaks, because pension funds and other innocent parties are entwined with them, they say to the government, “Whoops, we didn’t know this was going to happen,” and the government bails them out.

These looters are a dime a dozen. Unfortunately, they bring down countries and hurt a lot of people.

That fine paper is “Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit.” Somewhere in the comments to this fairly shrill blog post is a link to the pdf that those who don’t have a jstor account but don’t mind being called a cheapskate could use.

it’s funny, the ‘Penn Square Bank’ case is just about exactly what you describe.. the difference is that the bankers in that case had heavy penalties put on them, and the FDIC swooped in and liquidated Penn Square lickety split… some of the ‘upstream’ banks had problems, one failed IIRC and another one got bought out. i dont remember the government bailing anyone out though. i guess Penn Square’s problem was not making bad loans… it was that it didn’t make enough of them! It was small enough to fail.

Collusion and resulting price distortions serve as the most likely explanations…. Is it time for the Feds to consider a RICO investigation?

This post is hard to follow. It may make perfect sense to a CDO trader or legal advisor, but the average layman, congressman and/or senator may stumble over these passages.

“1. Demand for CDOs came not from long investors, who would be concerned about credit losses, but primarily from (a) short investors . . . (b) investment banks . . . (c) correlation traders.”

and, several paragraphs later . . .

“Having a single affiliated party take down the riskiest layers of subprime deals means that normal arm’s length pricing was not operating, and the profit potential of CDO issuance, rather than investor demand, was driving the market.”

and later . . .

“In addition, the CDO manager would work hard to find investors in the CDO to pay off the loan from the investment bank.”

The last of the three quotes seems to imply that there were long investors, somewhere downstream, driving (or at least cooperating with) the provision of demand for these bonds. This seems to contradict the previous two quotes. The notion that demand was driven exclusively by shorts seems to be a theory that some form of “immaculate conception” gave birth to these monsters.

I very much appreciate the integrity and effort behind posts like this. It seems to me they are hugely important insights that need to be publicized.

I just wish they presented the mechanics somewhat more clearly, so that a layman audience could sidestep the jargon and better understand the process.

craazyman – you have hit the nail on the head. part of the arrogance was coming up with something so complicated that no one could understand it, reverse engineer it, monitor it or criticize it – simply be in awe of it and its profits. i can assure you, even the people who came up with it never really understood the myriad and complex risks – but worse, they did not care and were not made to.

No, they knew. See Backwardsevolution’s post above citing William Black. It’s conspiracy to defraud the government of the United States. GS bagman posted in US Treasury. Ready, set, extort.

I find all the “complication” to be noise hiding the root of this. This was the crash of a pyramid scheme. This gained the momentum it did for the same reasons, and crashed for the same reasons, as any other pyramid scheme.

Brilliant post, Mr. Tom, and craazyman makes a valid point so please allow me to simplify:

Credit derivatives are used for super-leveraged speculation which allows for the rigging and manipulation of the markets, be they commodities, precious metals, energy, oil, etc.

The largest single chuck of credit derivatives are controlled (and the word “control” is essential to this discussion) by the top five banksters: Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Citi and BofA.

When one backtracks the financing of the pivotal and crucial coporate and organization entities along the way (e.g., Markit Group, InterContinental Exchange, ICE Futures, etc.) those five banks are ALWAYS involved.

When one backtracks even further, to the Group of Thirty promoting the adoption of complex securitizations and wider spread usage of credit derivatives, that report coming out of JPMorgan (Glass-Steagall: Overdue for Repeal), the make-up of the Derivatives Policy Group and what legislation they were promoting, etc., etc., etc., the overall design becomes obvious.

Equally important is for more people to grasp that the majority of the US economy is made up of leveraged speculation, with approximately 97% of world economic activity comprised of foreign speculation.

I hope things becoming a bit clearer now…..

nicely laid out and connected.

another factoid – a good number of CDO desks were investing in the mezz tranches to get a deal done, or as you laid out, providing credit to the CDO mgr to do the same. when the mezz pieces started adding up, some risk mgrs started asking questions. the result? there were basically two categories: 1. the risk mgr got fired or re-assigned or 2. the desk was required to MTM their mezz pieces and were charged losses to their bonus pools. Guess who kept adding the mezz pieces?

I can summarize this with one four letter word:

R.I.C.O.

Don’t suppose there’s much chance of it happening…

But I wish this blog were required reading to work for the SEC, hold public office… or maybe even to vote!

Complexity and the ‘ignorant bliss’ of their ultimate marks (you know… regular citizens who thought it was smart to trust well-dressed ‘experts’) have given Representative Government a bad name.

Consider your home loan. There is the note and there is the mortgage or deed of trust. Consider a CDO its requisite companion is a CDS.

If you bot the CDO and a CDS against it, you’ve transfered your risk inherent in the CDO to the counterparty who sold you the CDS.

Please help me to understand why anyone would write a contract to settle at face, or some other substantial amount, a contract that was either by design or accident going to fail.

There is no greater fool than the fool who thinks there is a greater fool.

The mistake in your thinking (not really your mistake as this is how it is always being framed) is the usage of the word “bet” (typo as “bot”).

They aren’t truly bets, but really leveraged speculation, and layers of leveraged speculation at that.

This is crucial to understanding the macro picture.

You obviously have a lot of excellent knowledge, and make many very good points, so I like to hear what you have to say. However, one of your comments is so convoluted that it makes me think you are trying to warp the facts to fit your conclusion. You say that demand for CDOs “came not from long investors, who would be concerned about credit losses, but primarily from (a) short investors who wanted to bet aggressively against the housing market and needed a tool to allow them to do so without disclosing their real intentions.” Short speculators encouraged investment banks to stimulate demand from investors to buy or otherwise assume CDO credit risk, but the demand came from the long side. There is no debate that much of this demand was naïve and simply relied on credit ratings.

One source of demand came from the monolines. In contrast to the rating agencies, who assumed no direct economic position in the CDOs, it was the monolines’ jobs to evaluate and take a position on the credit risk of these transactions, and they failed in a miserable way. They were unique in terms of their infrastructure and perspective, and they even had a (long-term) financial incentive to identify the credit bubble and put on the brakes, but they decided in favour of short-term gains over long-term credibility and viability. In my view, the monolines are in the same league as the investment banks, rating agencies, and sleepwalking regulators in terms of their culpability for the crisis.

Hard to argue with the point that monolines contributed substantially to the problem. They didn’t rely exclusively on the rating agencies either, so they (I) can’t point the finger elsewhere.

my point is that they weren’t enough of a factor to drive the market. So far, we’ve only been able to identify 3 of the 30 Magnetar deals that were insured. Where did the rest go? None of the big monolines were on the Abacus deals, AIG did 7 of them and ACA did one or two – yet there were over 20 of these deals.

I’m not making excuses – i’m just trying to find out how the market really worked and the standard explanations are not satisfactory.

Thank you for responding. Your response makes me think I may be guilty of what I accused you of – molding the facts to fit my thesis. I was debating what I thought was an apology (by you) for long investors (including the monolines).

I understand your point that, even though the end demand came from buyers, it did not derive from investors who performed diligent analysis and decided that they wanted to buy these monsters. It was largely stimulated by the investment banks that relied largely on bogus ratings.

Even though the monolines were not dominant in the market, I think it is very unfortunate that they did not try to apply the brakes and warn the rest of us. It sounds as if you might share this view.

I sure do. It has cost me many sleepless nights. I wasn’t quiet about my concerns about the market but I was wrong about what to do about it.

Regarding the bank “demand” for MBS – the void in real demand for MBS (and mortgage loans) was filled by CDOs. Much of the demand for CDOs came from the banks who got paid a ton of money for making the CDOs. The final resting place for those “end” CDOs, insured or otherwise, was the banks or the banks off balance sheet vehicles. If a bank reached capacity for taking down its own CDOs, the CDO team would pick up and go to a bank that would be willing to take them down (see the Calyon team and the Magnetar trades) and willing to provide guaranteed contracts. Remarkably, when the Calyon team left for Mizuho, Calyon regretted its capacity limits and sued to prevent Mizuho from taking the team.

Thanks again for the comments.

The Calyon-Mizuho story is pretty funny and ironic.

Tom –

Did the monolines insure synthetic securities? Or only the actual underlying bonds?

I thought only AIG was doing the synthetic deals. If that’s the case, it seems the monoline factor was minimal compared to the damage created by synthetics, and the entities involved in creating them.

PS – I’m also curious if AIG was so big in doing CDS deals in 2005 – how come none of the monolines mention AIG as a competitor in their Annual Reports?

I’ve only observed evidence of AIG and ACA, not the other insurers, doing pure sythetic ABS CDOs like the Abacus deals. AIG insured 7 Abacus deals, the rest of their portfolio of ABS CDOs was either cash deals or “hybrid” – a mix of cash and synthetic collateral (that’s what the Magnetar deals were, too). I don’t think the synthetic deals did more damage than cash or hybrid ABS CDOs – they were all bad and damaging.

Good question on AIG not being mentioned as a competitor – I never noticed that. It does seem like an odd ommission, though they did not compete with each other in the municipal market – AIG was not a participant there.

Tom – thanks for your response.

I agree the omission is odd. In fact, I find it strange that AIG was supposedly so active in the financial guaranty business in 2004/2005, and yet they were never involved in the trade organization AFGI. From their website:

“The Association of Financial Guaranty Insurers, AFGI, is the trade association of the insurers and reinsurers of municipal bonds and asset-backed securities. A bond or other security insured by an AFGI member has the unconditional and irrevocable guarantee that interest and principal will be paid on time and in full in the event of a default.”

http://www.afgi.org/whoweare.htm

What does it say about Goldman that they supposedly placed so much at risk with a flakey CDSs guarantor that wasn’t even part of this professional organization?

Also, how come Moody’s and S&P NEVER mentioned AIG in their industry forecast newsletters from the same period?

I’d be happy to share my information if you find any of this interesting. You can contact me through the email I registered with your site.

Thanks you and Yves, and George, for your terrific research and reporting on NC. I have great respect and a lot of appreciation for what you do.

Regards –

Goldman lives!

The GOP will pretty much neuter any further attempt by the SEC to pursue Goldman.

//////////

GOP ramps up attacks on SEC over porn surfing

By DANIEL WAGNER (AP) – 1 hour ago

WASHINGTON — Republicans are stepping up their criticism of the Securities and Exchange Commission following reports that senior agency staffers spent hours surfing pornographic websites on government-issued computers while they were supposed to be policing the nation’s financial system.

……

Schapiro has been parrying GOP complaints about the Goldman Sachs lawsuit, which agency officials hoped would mark a new era of tougher oversight of Wall Street.

Republican lawmakers also accused the SEC of being influenced by politics. The SEC’s commissioners approved the Goldman charges on a rare 3-2 vote. The two who objected were Republicans.

“The GOP will pretty much neuter any further attempt by the SEC to pursue Goldman.”

As long as there are non-thinkers like you, who are forever falling for this Team A against Team B, or Team Red against Team Blue, we’ll never make any progress — and for the past forty years we have definitely been retrogressing.

The point being: from every presidential administration, at least starting with the Nixon Administration (and including Carter and Clinton) up to and including the Obama Administration, the people they appoint are fundamentally the same.

Linda Chavez, who started that neocon “think” tank, the Manhattan Institute, was first appointed by Jimmy Carter, and reappointed by Ronald Reagan. George W. Bush attempted to reappoint her again (but she evidently had too many below-minimum wage illegals working for her).

Eliot Abrams, began under Carter, reappointed under George W. Bush.

The stupid newies on the payroll keep repeating that Larry Summers and Timothy Geithner are from the Clinton administration, but they both were first appointed by George H.W. Bush (Bush #1).

Obama’s first appointment: Henry Kissinger as special envoy to Russia (or did that happen to get by you????).

Over 50% of Obama’s top appointments have worked for Henry Kissinger at some point in their political lives.

Do you have any idea who Diana Farrell is (aside from being one of Obama’s earliest appointments)??? Or how she came by her big bucks? Or just how anti-worker, anti-labor, anti-union she — and all the other Obama (and Bush, and Clinton, and Bush, and Reagan, and Carter, and Nixon) appointments are anti-worker, anti-labor and anti-union????

Until people like you start paying attention to what’s really going on, we’ll continue to live in an ever downward spiralling binary world….

It strikes me that all of these actions could occur with or without explicit collusion. Were not the incentives arranged in such a way that these behaviors were income-maximizing for all involved? If so, it would not necessarily require a secret agreement amongst the parties, which is at the core of the definition of collusion, for this to occur.

So is this a case of incidental collusion, or were the higher ups at these institutions orchestrating this dynamic? Or, alternatively, did the people who designed the incentives know full well what the outcomes would be and accomplish collusion in that manner?

If you believe it was intentional collusion, I would be interested in what drives you to that conclusion.

I don’t mean to presumptively answer for Mr. Tom, but please allow me to repeat and elaborate:

When those ostensibly responsible for neutral pricing of the product (such as the Markit Group and others) are financed by the same banksters that are selling the product (Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Citi, etc.), as well as being the principal traders involved in “wash trading” (Goldman Sachs & Morgan Stanley at InterContinental Exchange, etc.), and when the principal exchanges always seem to be financed/owned by the same banksters (ICE or InterContinental Exchange, ICE Futures, etc., DTCC, Swaps Wire, Climate Exchange, PLC [owner of the other climate and insurance exchanges around the planet], ELX Futures, etc., etc., etc., the potential for control, deception and manipulation becomes simply extraordinary.

Who owns Phibro? Citigroup, of course. Who owned the bulk of BlackRock (now Bank of America)? Merrill Lynch, of course.

And on it goes…..

I think it would be more instrumental to divide the pack into two groups.

First one was those (as Citigroup) who honestly believed that securitization created a ‘gold mine’ and tried to exploit that possibility.

Another one was those (like Goldman, Paulson and Magnetar) who understood that CDOs’ conventional evaluation was based on the wrong premises and tried to exploit that fact.

That is such utter and pure bulltwacky!

Citigroup, where the SIV (Structured Investment Vehicle) was created in 1988. A major investor in NAFTA so that they could recover their drug money laundering business (along with the other major banks) which fled to the Mexican banking sector after the lowering of reportable deposits by the bank reporting legistion of the ’80s.

Give me a frigging break! The usual suspects: Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Citigroup and Bank of America.

‘Nuff said….

I don’t get your point. Do you agree or disagree that there were two distinct driving forces there?

P.S. Btw, both these forces are of ‘criminal’ nature. So, we could observe two groups where first group was looting public and another group was planning to cannibalize on their criminal partners.

Tom, I note that you are a lawyer. I also note that you have studiously avoided the legal questions many of us have regarding the convoluted CDO trade which seems at least deceptive if not fraudulent. Were securities laws broken? Should a grand jury be empaneled to gather evidence and issue indictments? Might there be the mother of all RICO cases here? I know you have thoughts along these lines – how could you not? And yet, you have chosen not to respond to queries along these lines. So, let me ask you directly, why haven’t you joined, nay led, the chorus screaming for criminal indictments and prosecutions? You have very effectively identified the actions which led to this mess. Wouldn’t prosecution be a better next step than attempting to correct policies that have failed?

well, complex securities litigation is not an area of law I practice in. when I was actively in the securitization market prior to the collapse, it was as a business person, not a lawyer.

I am cautiously optimistic that there may be more actions brought in these areas, though I suspect there will be more activity in private litigation, than government led actions.

So, with posts like these, I’m pointing out what I observed, which certainly looks like it was problematic, legally. Getting government agencies to bring these types of cases, however, is easier said than done.

Yves, Are you familiar with Chris Whelan’s work relating CDS to insurance company (ie. AIG) “side letters”?

He posits that when regulatory scrutiny (a very rare bird)focused too much on that issue, a shift to CDS’s was made.

Thank you for your work.

Lee S

IMO there are three root causes of the CDO-driven financial collapse that have not been adequately addressed:

1. The black box nature of the various asset-backed secutrities and CDS instruments created by WS over the past twenty five years have resulted in interlocking financial risks that no one understands. WS should not be shocked by new laws and regulations designed to improve transparency. No one should be shocked when said laws and regs result in new complex financial instruments that no one can yet envision, which will result in an even bigger crash, bringing on the next financial crisis at the end of the next business cycle. New rules and regulations will not solve anything without real game-changing tectonic shifts.

2. The rating agencies provided the oxygen needed for the CDO and CDS contagion to spread and burn as high as it did. Clearly, they did not ( or chose not to )understand the nature of the underlying mortgage risks, and had no need to given that sellers were compensating them to provide the credit marks neccessary for the game to continue. Rating agencies need to be compensated by buyers, not sellers, and the raters need to keep sufficient ownership in the stuff they rate to ensure that their interests are aligned with buyers interests.

3. Over the past twenty five years, WS has quite cleverly shifted the risks from themselves (where it was back in the day of partnerships) to shareholders and ultimately to taxpayers. This needs to be reversed. I don’t think it is an accident that GS was the least impacted by this stuff, given the fact that it appears to me that more of their execs personal wealth is in GS stock than at other WS firms.

i found a funny ad in the back of “derviatives week” issues circa 2004. It says this:

“Merrill Lynch:

We could tell you what we’ve acheived in the CDO market, but the results speak for themselves”

“#1 global underwriter of CDOs in 2004”

it then lists a grid of 30 ‘plaques’, each one representing a CDO deal, listing the size of the deal in dollars, and the ‘partner’ company.

It is kind of weird to read the company names:

MBIA (now dead, wrote CDS on CDOs)

ACA (see the Goldman SEC lawsuit)

AXA (a monoline IIRC? )

Mizuho (fired all its CDO people in 2007, see magnetar)

Tricadia CDO Management (WSJ and NYT both accuse them of magnetar-ish trades)

Rabobank (suing someone over CDO iirc)

etc etc