By Rob Parenteau, CFA, sole proprietor of MacroStrategy Edge, editor of The Richebacher Letter, and a research associate of The Levy Economics Institute

Richard Alford has correctly identified the need to address global imbalances – rather than simply slouch our way back to some milder version of status quo before the pre- Lehman meltdown arrangement, as we presently appear to be doing – if we are to have any hope of finding a sustainable global growth path. On this much we can surely agree. As to the method of addressing global imbalances, however, and perhaps even the true nature of these imbalances, we find ourselves deeply at odds with some of his diagnosis and most of his prescriptions.

Richard specifically takes issue with those of us who have been warning about the pursuit of large, prolonged fiscal retrenchment paths in the eurozone. He believes this is a bit of a diversionary tactic on our part, akin to a stance John Connolly once took, of restating our problem as their problem to deal with, not ours. The solution to the US problem is plain and simple in Richard’s mind: stop fighting austerity policies abroad, and start advocating their implementation at home.

Now it is true, as a matter of double entry book keeping, that if the US as a nation is going to reduce the gap between its spending and its income (which would reduce the currently widening trade deficit by definition), then nations that are major trading partners of the US must be prepared to reduce their net saving. Just as it takes two to tango, there are two sides to every exchange or transaction. One nation cannot increase its financial balance or net saving with the rest of the world unless the rest of the world is prepared to reduce its net saving. So from a rational perspective, rebalancing global growth does, as a matter of fact, require both sides to move in the right direction. This is not a theory – it is simply an accounting reality. One side can initiate the move, but both must be prepared to move.

Frequently, we are told by neoliberals, who dominate the economics profession and policy making circles, that there is something called the “twin deficits” that must be recognized and addressed in the US. The twin deficit story goes like this: an increase in the fiscal deficit will tend to lead to an increase in the current account (or trade) deficit. Therefore, if reducing the US current account deficit is a desirable if not a necessary policy objective, then it is surely necessary to reduce the fiscal deficit. We have been hearing this story for nearly three decades from the neolibs.

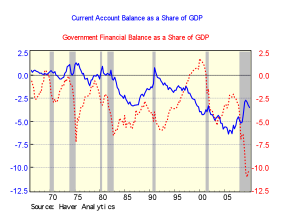

The problem with the twin deficit story is the facts do not seem to bear the theory out. Below you may observe a chart for the US the shows the current account balance as a share of GDP, and the combined government fiscal balance as a share of GDP. You will notice the twins seem unrelated – not even separated at birth.

Specifically, look at the entire decade of the ‘90s, when the twins moved in opposite directions. The fiscal balance increased, while the trade balance fell. This is supposedly impossible under the neoliberal twin deficits story. Then observe the shaded bars, which encompass recessions of the past 45 years. Lo and behold, in nearly each of the recessions of the past nearly half century, the fiscal balance has fallen while the trade balance has risen. The facts indicate the twin deficit story is at best an incomplete or unreliable story (click to enlarge).

Why might this be the case? The neoliberals are not playing with a full deck – or at least they are keeping some cards up their sleeves. In prior articles, policy briefs, and public presentations, we have traced out the fact that while for the economy as a whole, total saving out of income flows must equal total investment in tangible assets (houses, plant and equipment, etc.), this is not true for any one sector of the economy. Breaking the economy down into three sectors – government, foreign, and domestic private sectors – we can derive the following identity which must hold true at the end of any accounting period (we can provide the simple algebra to derive this upon request – it appears in other publications of ours, as well as in much of the research Wynne Godley performed while at the Levy Institute):

Domestic private sector financial balance + government financial balance – current account balance = 0

Or

DPSFB + GFB – CUB = 0

This means in order for the current account (CUB) and the fiscal balance (GFB) to be twins, as the neoliberals often assert, such that a fall in the fiscal balance (say an increase in the fiscal deficit) leads to a commensurate fall in the current account balance (say an increase in the trade deficit), then there must be little or not change in the domestic private sector financial balance (DPSFB). This, it turns out, is empirically false. The DPSFB is rarely stable, especially in the past two decades of serial asset bubbles, when both the household and nonfinancial business sectors have gone deeper than ever into deficit spending territory under the influence of asset prices kiting ever higher.

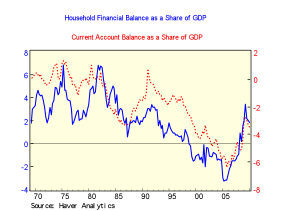

So what is the true twin of the trade deficit? We can split the DPSFB, as we hinted just above, into the household and nonfinancial business sectors.

DPSFB = HFB + NBFB

When we do so, we notice a new set of twins arises from the historical data. The true twin of the CUB is the HB, or household financial balance. And of course, this makes perfectly good sense since most of the trade deficit is in the area of tradable consumption goods (click to enlarge).

So if we decide the US CUB needs to turn around, we best find a way to increase the HFB, or the net saving positions (saving minus investment) of the household sector. How can this be achieved? Expanding and rearranging the accounting identity above, we find:

HFB = CUB – GFB – NBFB

If we want to get the two true twin financial balances increasing in value (thereby reducing the current account or trade deficit) then we have two choices available. Either reduce the government financial balance (increase fiscal deficits) or reduce the NBFB (get businesses to run down their free cash flow positions by reinvesting more of their profits in tangible capital equipment). If we rule out the former on neoliberal concerns about fiscal sustainability, we are left with but one choice to improve the position of the true twins, and that is a higher reinvestment rate in the domestic business sector.

And this, dear reader, brings us to the heart of the matter. Remember the global savings glut you keep hearing about from Greenspan, Bernanke, Rajan, and other prominent neoliberals? Turns out it is a corporate savings glut. There is a glut of profits, and these profits are not being reinvested in tangible plant and equipment. Companies, ostensibly under the guise of maximizing shareholder value, would much rather pay their inside looters in management handsome bonuses, or pay out special dividends to their shareholders, or play casino games with all sorts of financial engineering thrown into obfuscate the nature of their financial speculation, than fulfill the traditional roles of capitalist, which is to use profits as both a signal to invest in expanding the productive capital stock, as well as a source of financing the widening and upgrading of productive plant and equipment.

What we have here, in other words, is a failure of capitalists to act as capitalists. Into the breach, fiscal policy must step unless we wish to court the types of debt deflation dynamics we were flirting with between September 2008 and March 2009. So rather than marching to Austeria, we need to kill two birds with one stone, and set fiscal policy more explicitly to the task of incentivizing the reinvestment of profits in tangible capital equipment. A program to do so would include the following measures:

1) a prohibitive tax on retained earnings that are not reinvested with a 24 month period after they have been booked;

2) a financial asset turnover tax that raises the cost to businesses of playing casino games in various financial asset markets, rather than reinvesting profits in the productive capital stock;

3) a reinvigorated public or public/private investment program that helps speed up the shift to, and lower the costs of production of new energy technologies.

Regarding the last proposal, we must be willing to recognize the history of US economic development includes a number of very large and very bold public and public/private investment initiatives that provided numerous business opportunities and the basis for breakthrough technologies to emerge. The canal, railroad, highway, and other initiatives were hardly the doorway to the communist gulag they are made out to be. Indeed, if anything, Asia has mastered the use of this approach to push one of the most rapid adoptions of capitalism ever.

We know we need to reconfigure our energy infrastructure – we knew it over thirty years ago. It is time to act, and the third proposal could include such measures as solarizing all government buildings in the southern states in order to drive unit costs of solar cell production down, which in turn would increase the competitiveness of US producers of solar cells in global markets. There are undoubtedly more proposals we could bring to bear on the business sector to break the global corporate saving glut and force capitalists to act as, well, capitalists, but for the moment, this is a good enough place to start.

To conclude, Richard summarized his recent Naked Capitalism piece as follows: “The structural problems are reflected in mutually determined unsustainable current account and fiscal deficits, as well as depressed saving rates.”

Notice how his statement fingers the wrong twins – the fiscal and current account deficits are asserted to be mutually determined. Neoliberals tell this fib all the time. Empirically, we have shown you this is false, at least for much of the last four decades of US history, Theoretically, we have shown you this is also a suspect assertion: if you bother examine the macrofinancial balance equation in its full form, you find the neolib fib requires an implicit assumption that the DPSB show little or no change over time, which again is empirically false.

Notice the emphasis on depressed savings rates needing to be reversed and revived, when, as we argued above, the real source of US and global imbalances is a corporate savings glut. Firms are earning generous profits, but they are not reinvesting them in tangible productive assets. This visibly short circuits long run growth prospects, and is the foundation of the structural problem Richard alludes to, but we doubt he would recognize it as such.

That neoliberals with credentials, credibility, tenure, and positions of policy influence can continuously assert these glaring misconceptions is either malpractice, malfeasance, or both. It is not our place to speculate on their motives, though we have our own hunches (here is a heavy hint: just follow the money). Call it innocent fraud if you must, but neoliberals would have us marching to Austeria on the basis of their hollow, unsubstantiated slogans. It is high time for the neolibs to finally drop their fibs and step out of the way. Sorry Lady Thatcher, but there is an alternative to Austeria.

*Earlier in the month we coined the terms Austeria and Austerian Economics. We introduced these concepts in our June 10th BNN TV interview, and in our June 11 Richebacher Letter Weekly Alert to describe the policy stance we saw the G-20 embracing for Austeria, formerly know as the eurozone. (And yes, bloggers elsewhere who have been erroneously attributing these terms to Mark Thoma’s subsequent June 17th use of it at Economist’s View – please consider doing a little fact checking now and again).

One data series does not exhibits any meaningful correlation and does not fit; thus, the Neolibs try to explain it away as…well, who knows?

The other data series (DPSFB = HFB + NBFB) exhibits a strong correlation and fits well; thus, it is most likely the correct explanation.

Yet, the first group is the one with all the trappings of power.

The Neolibs remind me of Lysenko in agriculture. In other words, if neolibs economists had to feed the world, we would all starve in no time.

Which, Francois, is why it is high time to ask whether the neolibs either do not understand the world we actually inhabit, or they are serving someone else’s interests – is it malpractice, or malfeasance, or both?

That this question is not asked, or if it is, it is done in the context of dismissing all economics as useless drivel, surprises me to this day.

I think it’s clearly the latter. How else can we explain the fact that after WE the people bailout the very scoundrels who got us to this point, and now they’re (and the wealthy elite) are doing fine, they all of sudden want to “austeritize” the rest of us. So, in essence, the regular person gets screwed both times. Where’s the sacrifice or “austerity” at the top? Where’s the real “leadership”?

Agreed Mannwich – we’ve been duped.

We need to stop letting ourselves be duped.

We can start by identifying who the neolibs are pimping for, and have been for sometime now.

That is why Obama hired in Rubin’s boys, Geithner and Summers, to key positions right off the bat. And who made very large contributions to Obama’s campaign?

Hedge funds.

Wondering why the financial reregulation legislation is so watered down? Wonder no longer.

Funny that.

These awful neoliberals, probably mostly global warming deniers and neocons with it!

This isn’t economics, its political prejudice. To get to the economics, what is needed is for the authors to state clearly:

1) what percent of GDP should we aim for total debt to be, and why?

2) what percent of GDP should the current government spending deficit be, and why?

3) what exactly should the government be spending the money that it borrows on? What programs?

The proposed tax, by the way, is harebrained. It will simply lead to unproductive investment, bubbles (defined as price levels in some areas which make return on investment impossible) and stagnation and unemployment as a result.

The fundamental problem the authors are not admitting is that much of the current government spend is impeding economic growth. To maintain or increase it, especially with borrowed funds, will have no beneficial effects.

Michel – I believe the neolibs have demonstrated a repeated pattern of malpractice or malfeasance. About this I am dead serious – we can all see the price paid for following their advice and subscribing to their world view. If you wish to make jokes about it, you are free to do so, but I do not consider serial asset bubbles that distort and undermine the underlying real economic structure and leading to financial crises, deep recessions, and prolonged periods of unemployment much of a laughing matter.

Regarding your question on public debt limits, rememberr that the public debt is a stock at a point in time, and it is made up of the accumulation of flows, namely the government financial balance, over time.

The appropriate fiscal balance in any accounting period is the one that, given the existing private sector preferences to invest in tangible assets and save out of income flows, gets you to full employment with price stability. This, I believe, is what we need to recognize is the true definition of a sustainable fiscal balance.

The appropriate public debt load is the one resulting from doing just this – maintaing a sustainable fiscal balance -over time.

The fact is there is no magic, fundamental limit to the public debt/income ratio, especially for a nation with a sovereign currency (that is, money that is not convertible on demand into fixed units of another currency, or a commodity).

Rather, it all depends upon private investor perceptions and portfolio preferences. These, we know from experience in repeated asset bubbles in recent decades, are not well grounded in fundamentals or reality, and can be quite unstable and fickle.

Why, for example, did global bond investors wake up toward the end of 2009 and decide eurozone fiscal balances were on a an unsustainable trajectory – why had their eyes remain closed to this possibility for the two or more prior years of rising fiscal deficits amongst the GIPSIs?

Further, I believe it can be shown the Reinhart/Rogoff 90% debt/income rule is a bit of a canard at best, but that is a subject for another blog.

As for where fiscal expenditures should be focused, I would suggest public and public/private investment initiatives are needed and historically have proven very effective. We’ve done this in the past – spurring new waves of growth with canals, railroad, highway systems.

We’ve known we’ve needed to do it again with regard to new energy sources and infrastructure for over three decades. But ideological blinders, myopic financial managers and investors, and political corruption have kept us from executing. The hour, I think we can all agree, is getting late in this regard, and I also recognize we need political reform first if this is not going to turn into another exercise of pink elephants and political favoritism. This is no small order, but it is time to get it done.

Where such investment initiatives fail to bring the economy to a point of full employment with final product price stability, I would use and employer of last resort program trained on reviving natural and human capital through a focus on environmental remediation, education, community building, cultural enrichment, etc.

Regarding your reservations on my tax, I think we have seen repeated waves of irrational investment under the guise of maximizing shareholder value. Forcing capitalists to act as capitalists rather than looters or speculators might just be a good thing in light of this experience of the past three decades. I will take any and all suggestions on a better mechanism to get this result than the simple one I propose above, but I will not concede the fundamental point – something along these lines needs to be done at once to make capitalist economies run like something more than a casino.

Running an economy for the short run winnings of financiers has not worked very well for anyone but the shrewdest, most sociopathic financiers, has it?

I agree with your proposals wholeheartedly, but fear the divisive effect of money dooms them to short term success and not long term fiscal sustainability, unless the deeper conequences of money itself (as a tool for dealing with the problem of scarcity) on society generally are addressed and debated openly.

Can a tool, which logically and inescapably means being financially rich is better than being financially poor, lastingly bring people together in the community spirit you so rightly advocate? Social divisions are deep and bitter, and stubbornly refuse to go away. It seems to me the power money allows the rich lies at the root of this age old problem, rather than ‘human nature.’ And while I don’t believe all humans are born equally able, not only does money over-reward ‘success’ and over-punish ‘failure,’ it encourages hoarding which exacerbates the problem further, meaning small differences in ability result in disproportionately huge differences in quality of life.

Put crudely, the monetary systems we have known thus far have an inbuilt set of incentives, each arising from the presumption of scarcity, which erode community bonds over time. They prevent abundance where abundance would be otherwise be possible, benefiting from scarcity in terms of profit. I believe this is the main reason renewables have not been aggressively pursued. They threaten to yield abundant and clean energy for all, especially if combined with a needed revolution in housing and transportation. Existing technologies are therefore an existential threat to the energy industry and governments alike.

I’m currently reading Charles Eisenstein’s “The Ascent of Humanity” (and recommend it strongly). It’s available for free online. Chapter IV looks at this complicated issue in detail, though it has been addressed elsewhere too. The money system itself, at a deeper level than MMT offers, needs to be reformed before sustainability, whether fiscal or ecological, can reasonably be expected, in my view. To my mind, Bernard Lietaer is on the right track here, though more work is sorely needed in this direction.

This is wacko-fringe stuff I know, but I like to put it out there, just in case. ;-) Not only might I be wrong, or have missed something obvious, I might, heaven forbid, be right!

Toby – At this point, given the tremendous failure of conventional wisdom, mainstream views, etc. all we have left is to explore the fringes for solutions. So I will look at the chapters you recommend, although I find LETS systems too local and too small scale to be generalizable solutions, unlike MMT, but am open to persuasion.

best,

Rob

Thanks for the open-minded response, Rob.

I think MMT theories would dove-tail well with Lietaer’s multi-money suggestions. He does not push LETS at the expense of other money-types, but as one of many potential local money-types to compliment other local, as well as national, currencies (a la MMT), and an international currency for investment and trade (if memory serves), which would carry a demurrage of around 4-4.5% (again, if memory servers). He pushes multiple money-types to fulfil multiple purposes and reach sustainability by fostering diversity, and also to encourage the rebuilding of community. He’s on record in support of MMT, but thinks (and I agree) it does not go far enough.

In the end it will be trial and error of course, but there’s nothing wrong with that. All propaganda aside, trial and error is all we’ve ever had.

Toby

Toby . . . can you provide a link or two? Thanks.

Toby,

I think you and I are both converging on the same conclusion, and that is that there are much more profound problems here than just classical economic theory gone bad. Classical economic theory’s flaws are intrinsic. And yes, such heresy is “wacko-fringe stuff.”

What I find most surprising is how economists, such as Michael Hudson in the piece I linked below, can defend classical economics. It has almost always, from its first rattle out of the box, resulted in nothing but human misery and suffering, as was thoroughly documented by Simonde de Sismondi. In the first decade of the 19th century he visited England and was struck by the misery resulting from industrial progress. Why did the seemingly beneficial production of goods by machinery bring on “poverty in the midst of plenty?”

His detailed criticism of the new society includes the observation that it splits labor from capital and makes them enemies, with the power all on one side. The idea of their “bargaining” over wages is absurd. Tyrant and victim describes the relation, yet without cruel intent of the one or knowledge by the other of who his oppressor is. Again, with overproduction the capitalist must seek foreign markets and precipitate national wars, while at home a class struggle goes on without end.

Adam Smith was not an evil man. But he was a terribly naïve man. He “did not make the mistake…of giving simple moral sanction to self-interest,” the Christian theologian wrote in “The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness.” Instead, he “depended rather upon controls and restraints which proved to be inadequate.” Niebuhr marks Smith up in the “foolish children of light” column, “unconscious of the corruption of self-interest in all ideal achievements and pretensions of human culture.”

So if Smith is not evil, then who is evil?

Niebuhr defines the evil ones as “the moral cynics, who know no law beyond their will and interest, with a scriptural designation of ‘children of this world’ or ‘children of darkness.’”

“[E]vil is always the assertion of some self-interest without regard to the whole, whether the whole be conceived as the immediate community, or the total community of mankind, or the total order of the world,” Niebuhr adds.

It may come as a surprise to some that self-proclaimed atheists like the cultural psychologist Jonathan Haidt come to an identical conclusion:

Moral systems are interlocking sets of values, practices, institution, and evolved psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate selfishness and make social life possible.

http://thesciencenetwork.org/programs/beyond-belief-candles-in-the-dark/jonathan-haidt-1

I think you can see the unavoidable collision with classical economic theory here because, as David Sloan Wilson observes, the “individual who maximizes his own self-interest lies at the core of [classical] economic theory.”

So the bottom line is that bourgeois society (informed by liberal/classical theory) is every bit as vulnerable to what Smith calls “subversion” as the feudal society it replaced. In an analysis of early Calvinism, Smith discusses, as Niebuhr put it, the “stubborn, and ultimately victorious, conflict” the emerging commercial classes waged against the “ecclesiastical and aristocratic rulers of the feudal-medieval world”:

The question is whether Calvinism is designed to benefit some individuals (presumably the leaders) at the expense of others within the church, or whether Calvinism is designed to benefit everyone within the church as a collective unit. Exploitation is sometimes naked, but more often it requires deception. Thus, we might expect Calvinism to appear good for the group at first sight but to emerge as a tool of exploitation upon closer examination. Some features of some religions undoubtedly can be explained in this way, such as many practices of the Catholic Church that led to the Reformation. Religious scholars have already reached this conclusion on the basis of qualitative information, and there is little reason to challenge it. I am not trying to explain every feature of every religion as good for the group, nor could I succeed if I tried. It is multilevel selection theory that explains the nature of religion, not group selection alone. Churches are subverted from within, which in part accounts for the formation of new churches… However, the details of Calvinism point strongly to genuine group-level benefits rather than an elaborate sting operation.

I think Parenteau has his eyes firmly fixed upon the target, as I too am a utilitarian existentialist when it comes to public policy. I also believe that, as Parenteau seems to, that the age of the individual that we have lived for the past few decades is dead. A well-oiled group can produce resources that cannot be had by so many individuals toiling away in their private bunkers, as a functional group serves to increase the collective utility of its members. Human cooperation must evolve to a global scale, what Niebuhr called “the total community of mankind,” in order for humanity to find successful solutions to the problems it confronts, because the problems it faces are global in nature.

The trick is to find those things that facilitate group functioning, cohesion and cooperation. But neither the extreme individualism preached by the libertarians and classical economists, nor the “greed is good” creed proselytized by the New Atheists, nor the “suffering is good” creed embraced by the Austrian School and ascetic saints, works to this end. Quite the opposite—-all these contribute to group dysfunction.

Oops! A couple of corrections.

…what Smith calls “subversion”….

Should read:

…what Wilson calls “subversion”…

…In an analysis of early Calvinism, Smith discusses…

Should read:

…In an analysis of early Calvinism, Wilson discusses…

DownSouth, I’ve been noticing a convergence in our thinking too.

You said: “Human cooperation must evolve to a global scale, what Niebuhr called “the total community of mankind,” in order for humanity to find successful solutions to the problems it confronts, because the problems it faces are global in nature.”

BINGO! To survive and attain a sustainable socioeconomic system (and what other goal is worthy of our efforts?) we must transition forwards away from ‘enlightened’ self-interest and Invisible Hand thinking, towards a renewed hunter-gatherer-esque global community rooted in the local but networked enough to prevent dehumanization from occurring. This is an almighty challenge, and we might not meet it.

Economics contains nothing that I can find which redeems it. There are glimmers of hope in behavioural and biophysical economics, but for my money (ha ha) we need to start toying, intellectually at first, with post-scarcity economics — I suspect MMT + Lietaer will point that way in the end. Only by seeing the planet as the common heritage of all mankind — a post-scarcity corner stone — can we learn to share the abundant resources that are there, wildly scattered across the Earth. So much needs to be unlearned, so much hate and fear soothed, so much sociopathy confronted and stood down, it hardly bares thinking about. But as you so rightly say, it is sharing that is the way out of this mess. Sadly we are childishly addicted to the narrowest understanding of both competition and cooperation, so it is not going to be easy.

In the meantime, we all have to keep talking to one another as best we can, and finding common ground where we can too.

@stf: with pleasure. Try these:

Bernard Lietaer talk from 11.09

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nORI8r3JIyw

Charles Eisenstein’s brilliant “The Ascent of Humanity”

http://www.ascentofhumanity.com/

An interview Lietaer gave to Yes magazine a while ago (fascinating stuff):

http://www.yesmagazine.org/issues/money-print-your-own/beyond-greed-and-scarcity

Enjoy, and take it from there.

Toby,

“Abundance,” historically speaking at least, has been unachievable because humans keep moving the goalposts.

Here’s what Niebuhr had to say on the subject:

The idea that men would not come in conflict with one another, if the opportunities were wide enough, was partly based upon the assumption that all human desires are determinate and all human ambitions ordinate. This assumption was shared by our Jeffersonians with the French Enlightenment. “Every man,” declared Tom Paine, “wishes to pursue his occupation and enjoy the fruits of his labors and the produce of his property in peace and safely and with the least possible expense. When these things are accomplished all objects for which governments ought to be established are accomplished.” The same idea underlies the Marxist conception of the difference between an “economy of scarcity” and an “economy of abundance.” In an economy of abundance there is presumably no cause for rivalry. Neither Jeffersonians nor Marxists had any understanding for the perennial conflicts of power and pride which may arise on every level of “abundance” since human desires grow with the means of their gratification.

–Reinhold Niebuhr, The Irony of American History

Good quote DownSouth. It’s always important to remember that perfection is not only impossible, it is undesirable also. A society without conflict and desire would be lifeless.

That said, ambition, pride, desire, conflict etc., can each operate in different socioeconomic settings differently. There were of course wars between ‘rival’ hunter-gatherer groups, as well as internal conflicts (though without property theft is of course impossible), but escalation is avoided where possible, and rigid hierarchies are kept out of existence. I believe the presumption (if that’s the right word) of abundance, which is probably an offshoot of hunter-gatherer ’embeddedness’ in nature, is a key reason why their desires and ambitions did not become destructive conflagrations of the type we civilized peoples know so well. The people of St Kilda offer another example of the kind of life sharing can offer, this time sedentary. Theirs is a fascinating story.

For the rest of us seeking out a better path forwards, I believe the scarcity/abundance axis to be an important area for discussion. As the circle of reciprocity haltingly expands across national boundaries and even to include other life forms, while we simultaneously wield our powers of production and consumption as if there were no tomorrow, something has to give. Eisenstein talks of the Age of Separation ending and the Age of Reunion beginning, and he makes a lot of sense. I’m sure scarcity and abundance will play a key role no matter what transpires.

I just printed it off Toby. You are one of the brighter minds on earth. Glad you are still out there and I do miss our private conversations which we should resume shortly!

I don’t know who these neolibs are, or what they have done that has been so terrible. Terrible things are anyway not a monopoly of any particular subset of humans, terrible things have been done by adherents of almost every ethnic group, religion, geographical area, political ideology.

I also do not know what this so called austerity is. We are told that the UK is engaging in unparalleled austerity, yet it seems to consist mainly in making sure that people in receipt of disability living allowance really are disabled. That a bunch of government and quasi government departments which do nothing and should never have existed in the first place will reduce their expenditure by 25%. If that is austerity, bring it on.

I do not know whether neoliberals are responsible for the financial situation today, that’s a matter of which individuals took what decisions and which political grouping you put them in. What is rather clearer is where the problems originated. They originated in government interventions of various sorts. In the UK, the very well established and functional regulatory system was abolished by a government which was far from neolib, it was decidedly to the left of center. In the US, we had a series of grotesque blowups of money and credit bubbles, done on a scale that only a government could manage.

The problem was not that regulation was abandoned, and markets left to themselves. The problem was that government intervention in markets intensified, but with lots of unintended consequences.

On the question of what to do now, we have this: “The appropriate fiscal balance in any accounting period is the one that, given the existing private sector preferences to invest in tangible assets and save out of income flows, gets you to full employment with price stability….

The appropriate public debt load is the one resulting from doing just this – maintaing a sustainable fiscal balance -over time…..there is no magic, fundamental limit to the public debt/income ratio, especially for a nation with a sovereign currency….”

Perhaps so. If however you cannot say what exactly the size of the deficit that you wish to see is, and if you cannot say what programs you want to see the borrowing which accomplishes it spent on, then we are none the wiser.

There is evidence of a magic limit. The limit is around 100% of GDP. No matter what the purity of your intentions, when total debt reaches that level, you will suffer, and you will default. You can default in a number of ways. The idea that devaluing the currency is not defaulting is simply idiotic. The idea that a debt holiday and haircut is not a default is equally so.

It makes no essential difference whether you can devalue your currency. It just adds one to the number of ways in which you can default. But it does not change the fact that over indebtedness leads to default.

So, once again, take a concrete case. People are advising the UK not to cut borrowing, not to cut government departments, but to keep on spending. Where is there an historical case of a country that has done that, with a debt ratio of about 60%, a current deficit of about 11%, and produced economic growth and no default of any kind?

Don’t cite Japan. That was the lost decade or lost decade and a half.

The urgent need at the moment is to have an environment in which investment seems attractive. If that can be brought about, and it will mainly be so by eliminating deficits and state borrowing, and lowering government spending, then you have no need for epicyclical taxes on retained earnings and the rest of this stuff. The problem is, you are advocating increased debt in order to have increased spending on what will inevitably be more economy retarding programs.

We might just as well hire armies of people to go out and tear up the highways. It would contribute as much to economic growth as the government programs the UK is being so excoriated for cutting!

Michel – The Reinhart/Rogoff public debt limit is a canard.

Please, all of you who have been misled by this 90% public debt/income limit finding, go to the Levy Economics Institute website, and download working paper 603.

Reinhart and Rogoff do not have this right. There is no automatic magic cutoff point for public debt to income ratios.

In my earlier response to you I have addressed your other issues. Best not to repeat myself.

Your math doesn’t seem to work out.

I get your equation:

HFB = CUB – GFB – NBFB

And you are stating that HFB and CUB are the true twins, which if that is true suggests that (GFB + NBFB) does not vary much over time. I’m still with you, assuming your data is good then it seems to bear this out.

But what follows does not make sense mathematically.

You first say that if we want to increase CUB then we need to increase HFB. Assuming that (GFB + NBFB) continues to not show substantial change, then this is correct. But that is your key assumption in this statement.

You then say that if we want to get the true two twin financial balances increasing then we need to decrease either or both of GFB and NBFB, but at that point you are violating your own statements already made. If (GFB + NBFB) is going to decrease, then you are breaking the link between HFB and CUB.

Let’s think it through. You say we need to reduce either GFB or NBFB (or both, though you present it as either). So (GFB + NBFB) is reduced and thus the negative of this in your equation is increased. If CUB is held constant, then HFB must increase – you have solved for the one financial balance as promised. But if HFB is held constant, then CUB must decrease, the exact opposite of what you are promising.

So while you state that the way to increase HFB is by decreasing (GFB + NBFB), the only way that this is necessarily true is to take CUB as constant in your equation. But in doing so, you violate your assumption that HFB and CUB are twins. You can’t hold CUB constant in order to get HFB increasing, and then turn around and say that CUB increases because HFB increases.

David K:

“You can’t hold CUB constant in order to get HFB increasing, and then turn around and say that CUB increases because HFB increases.”

I think you must. The increase in HFB increases CUB *and* holds it constant. So the assumption is asserted.

David David David

The math is sound. Deal with the consequences of the math.

Mr Parenteau is right. The neo libs dont care about truth, the people they are appealing to never question their claims, especially if it sounds mathematical. They themselves know exactly what they are doing, they are not stupid they are simply greedy soulless bastards, who will use ANY argument to allow the upper 5% to continue to skim billions form the rest.

That is precisely my take as well. These people can’t be (and aren’t) THAT obtuse.

David:

If you agree that a trade deficit is a two sided affair – some domestic sector wants to spend more on tradable goods than it earns selling them, and the counterpart to that is a foreign nation that want to sell more than it spends – then question to ask is which US sector displays a financial balance that most closely follows the trade balance, right?

That sector is not the government financial balance, as is commonly, frequently, and I would argue, blindly asserted by the neolibs in policy positions and academia. It is not the business financial balance, although that has played a larger role, at least in the ’90s. Rather, as you can see for yourself, it is clearly and consistently the household financial balance that tends to move with the current account balance.

And of course, this makes intuitive sense given the build up in household debt loads, which is evidence of their defict spending, and the composition of the trade deficit, which is dominated by consumer goods produced abroad.

So we should be able to agree one of the keys to reducing the US trade deficit is to improve the household financial balance. (As an aside, the neolibs phrase this as the necessity of an increase in household saving, but it is really net saving, or household investment in tangible assets – mostly housing – minus gross saving out of income flows that matters as the full macrofinancial balance equation reveals. The neolibs, in other words, are dealing with an incomplete accounting framework – they only show you what serves their ideological purposes).

If the household net saving or financial balance is going to improve, and this is going to be the causal mechanism that improvese the trade deficit, then some other sector must reduce its financial balance (reduce its net saving or increase its deficit spending).

We then are left with three possibilities to increase the HFB:

1. Decrease GFB – i.e. deepen the fiscal deficit by cutting taxes or increasing expenditures

2. Decrease NBFB – i.e. reduce corporate net savings by incentivizing reinvestment of retained earnings in tangible capital equipment

3. Decrease GFB and decrease NBFB at the same time

I hope that clarifies the point I was trying to make in the essay above. If not, I am happy to try and walk through the logic of my position a different way until you can see it for yourself.

best,

Rob

WHO CARES IF SO WHAT DOES THAT BUY YOU AT THE MARKET?

GET OFF THE GRID

I am a sovereign American Citizen I will not bow down to the G-20 Banksters, none of those crookmasters were elected. CNN called that bunch lawmakers ??????

With all the many reasons for folks to protest contest and dissent, no wonder we even have a nation half fit half-wit people to do so.

But the simple truth of the matters about all our problems is in the cure if we will do so.

Meaning get off the GRID. Refuse to play the game that the tyrants have set out to make us play.

How hard can that be? Drain your bank accounts dry —- convert to spend able gold. Then set back, trim the sales, take a break, look around, lose all the un-necessary baggage, tear up the credit cards, drive less, spend less, eat right eat at home, tell the kids NO more often, put all on a strict budget.

Buy a cheap pre-paid credit card to buy stuff on the web. Get away totally from the crooked banks.

Take your mainframe computer and un- plug from the web.

Never plug it in again then tell all who might want to know “ got destroyed in a fire”.

By a cheap computer to keep at home —– put in on the web for nothing at all except to read etc. never take your private notebook with all your private stuff out.

Now do your best to be sane while your ride out this storm?

Last thought The Banksters G-8 and G-20 are shaking in their boots—- why else would they spend one billion for security?

They only rule because we allow them too.

Get off the D—mn Grid.

I welcome your plea for people to take power back into their own hands, Dwight, and to start taking simple steps of asserting their own initiative rather than expecting someone else to carry them through the fire.

But ask yourself, could all the inhabitants of NYC go off the grid, and if so, on what timeline and with what investment expenditures on small scale food and energy production.

Also ask yourself, even if you individually can find a homestead and go off the grid, what happens when the default world, mainstream society, derails? Do you really think they will stay out of your cabbage patch? Do you have enough ammo to keep the starving looters at bay?

As much as I love the image of rugged individualism and self reliance, having been born in a state where the license plates read “Live Free or Die”, I think we have to face the facts of contemporary society – going Daniel Boone will not work for hundreds of millions of people in America.

Accordingly, we best work together to take the future into our hands and make it a sustainable path if at all possible. To do so, we are going to need to clean up the political process, expel the sociopathic wing that is distorting markets, and figure out how to make democracy really work for the average citizen in the context of an environment that cannot just be pillaged, consumed, and treated like a toxic waste dump. We cannot continue to sh*t where we sleep, I agree, but whole cities are unlikely to become homesteaders either, so we have to find an intelligent path forward together.

The answer to why they are in such a hurry with austerity is that they are desperate to paper over the austerity perpetrated by them in the US by Wall Street policy over the last 20-30 years when each and every leveraged merger or acquisition resulted in huge leveraged fees for the likes of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. L.P. 9 West 57th Street Suite 4200 … Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. Ltd. Stirling Square 7 Carlton Gardens London SW1Y 5AD etc., here bloated stock options and millions of ‘downsized’ people at thousands of companies , eliminated benefits, eliminated journalism, imported garbage from slave labor, off shored profits, destroyed the justice system, tore up the constitution -ITS A LONG LIST.

The austerity rush is a symptom of their panic over GAME OVER -people all over the world GET IT.

apology -this is in the wrong place.

I had been writing a rant on NYC Bloomberg-style preparation for crowd control and past human rights crimes against peaceful demonstrators but got started on this other.

Lord Have Mercy!

Finally!

A macroeconomics article that nails the problem for what is is: the corporate savings glut and a failure of the corporate imagination.

YOu can break Economic Imagination (EI) down into Consumer Imagination (CsI) and Corporate Imagination (CtI)

and because GDP = Capital + Labor + Nature + Imagination, we can see that Imagination is a big component of GDP

where Imagination (I) = CsI + CtI

Now Imagination can vary between negative infinity (i.e. war, revolution and social collapse) and positive infinity (when Jesus comes in the clouds and we all ascend in the final eshaton).

Now CtI is very negative, CsI is also somewhat negative due to what George Soros would call reflexivity, but which I will simply call being broke, which is another way of saying that there’s a corporate savings glut and looting surplus.

Putting CtI into positive territory is like getting an addict to sober up. You can’t just ask nicely.

Craazyman, there is wisdom in your madness.

What we have here is a failure of our own imagination, and our willingness to actualize what we can imagine, which is one of the greatest gifts of being born a human being (although we also have to face the limitations inherent in the real world we inhabit too – it is not all about visualizing whirled peas and chasing The Secret with multi level marketing schemes).

But then, we have in fact allowed our imaginations to be cannibalized by corporate advertising and political huckstering. Hey, it was easy and it felt good while it was happening. We bargain with the devil sometimes, and the devil always gets his due.

So indeed, the time for detoxing has arrived, and I feel confident it can be done if we are willing to do it together in a true, small d democratic tradition, with the same swelling of imagination, true grit, and hard work of the founders of this nation.

Up for it?

Yes, I am up for it, although my imagination far outraces my mastery of the technical facts of macroeconomics, as does most people’s, including most so-called “economists”. ha ha

I agree with Toby that the nature of Money itself is a root problem, and it’s nature must be changed for society to better channel logos and repress thanatos, which I believe is a primary function of well-designed monetary systems.

I am working — usually after a few glasses of cote du rhone — on what I hope will eventually be a synthesis of psychoanalytics, anthropology, economics and political economy, which may inform the ideas for a revised political economy. But this may take me a while, because I have other distractions such as my interest in the arts.

This field of thought I call “Contemporary Analysis” and I’m a Professor at a place called the University of Magonia, which exists only in my own imagination. But so does the world itself, and so do we all in our own.

But your posts do help me in my work, and I appreciate them. Maybe I will eventually say something that is useful to the larger effort. In the meantime, I’ll keep talking anyway, regardless of how little sense I make.

–The canal, railroad, highway, and other initiatives were hardly the doorway to the communist gulag they are made out to be.–

I donno. I’ve always suspected that the Erie Canal was a communist plot.

Biggest pile of Krap I have ever read on NC. Back to whatever clueless interventionist hell you came from, and change the name of your service to something more truthful like “Moron’s Strategic Edge”. Some truly idiotic initiatives suggested.

Color me Austerian.

KAK – Am happy to address any issues of substance you take with my views. Ad hominem attacks, however, will get you nowhere. Please take your spew, join the Know Nothing Party, and have a nice austerity!

best,

Rob

An extremely well-written piece. Certainly better than the majority of what guest posters have produced here recently.

Interestingly enough, it’s not all that different than what Keynes suggested in the General Theory (which has little resemblance to what the Keynesians that followed him tried to implement). Keynes identified investment as the key unstable variable, called for splitting the government budget into an operating budget and a capital budget, wanted the operating budget to be in balance at all times, and wanted the capital budget to swing into deficit or surplus countercyclically to address the instability of private sector real investment.

Rue –

Yes, what Keynes actually wrote, and what the so called Keynesians (Samuelsonians/Robertsonians/Hicksians, really)wrote, are not the same thing.

Because so few people read Keynes in the original, including tenured neoliberal professors calling themselves New Keynesians, this misrepresentation of his views has been perpetuated much longer than it should have.

Glad you understand this – wish more people did. Keynes argued public investment on the capital budget was your primary tool for full employment with price stability if monetary policy came up short. Countercyclical fiscal policy on the current account (aka pump priming), of which there is very little mention in the General Theory, was a last resort which he did argue needed to be reversed during expansions (if the fiscal deficit on current expenditures and revenues did not reverse endogenously) on its own.

Rob, what do you think of Steve Keen’s work, the only model I know of that actually implements what Keynes said?

…What Keynes said mixed with Minsky.

Mikkel – I am currently sitting at a Minsky conference with Steve Keen, who I count as a personal acquaintance. Which model, or which part of his Minsky inspired models, are you looking for me to comment upon?

He is one of the few to mathematically formalize Minsky financial fragility dynamics, with some promising results, although he takes some circuitiste twists I would not.

best,

Rob

It’s nice to see you decomposing the private sector balance (finally?).

But I think I’m with David on first reading.

You’re trying to improve the current account. Both private sub-sectors make directionally positive contributions to current account improvement (i.e. more positive for either households or business means more positive for the current account, ceteris paribus.)

But you invoke the need for primary correlation between household and current account balances.

So you want to get the household balance up.

Then you do that by freezing the current account result whose improvement is the original objective.

And so you reduce the business balance to get the household up, and then invoke correlation, and so on.

Reducing the business balance means more investment.

It seems like a lot of faith is involved in the sequencing.

Without faith in that sequencing, I might say that increased investment increases the current account deficit, other things equal.

But this is only my first impression. Need to read it more.

P.S.

Presumably you omit the financial sub-sector because it nets to zero. If that’s right, I understand it, but it makes me uncomfortable for some yet to be determined reason.

All at the margin, it’s like corporate surpluses are working in the same direction as government surpluses – in terms of being a catalyst for household deficits. So the deleterious net saving effect of government surpluses on the private sector is compounded by similar corporate effects when that flows through to the household sector.

The optically weird thing about this is that the business sector financial balance is chronically negative in both stock and flow terms, due to its net real investment position. So the SFB issue is whether it is negative enough.

Anon – actually, post burst asset bubbles, the nonfinancial business sector tries to (and succeeds, if the fiscal deficit widens and the current account deficit shrinks enough) raise its net saving or financial balance position. This of course complicates the capacity of the household sector to also achieve a high (mostly precautionary) net saving position.

In addition, professional investors have been favoring companies with high free cash flow (that is limited or negligible reinvestment of profits) since the LBO and corporate raiding days of the ’80s. At the macro level, this is the equivalent of investors betting and making money on the murder and death of capitalism. But they are all just maximizing their personal wealth and the wealth of their clients, so they cannot see this forest, as they are busy gnawing away at the roots of the trees.

best,

Rob

Right. I haven’t looked at the numbers, but the non-financial business sector can’t improve its net financial asset position in flow/stock terms unless it actually reduces its net real asset position in flow/stock terms, can it? I.e. real capital stock actually has to shrink, which means the net financial liability position shrinks. Has that actually happened?

not all nonfinancial corporate business debt is used to position tangible assets – quite a bit of what the Japanese called zaitech, or financial engineering, got into the system over the last two decades

Maybe I’m being repetitive here, but it seems to me the improvement in the business net financial asset position can only happen via depreciation that isn’t replaced in gross real investment terms. I.e. it’s depreciation that improves the sector NFA.

Unenlightened self-interest in-action, undermining democracy and corrupting capitalism. Seems I’ve read something recently along those lines; not sure where, but I think we’ve been econned!

Thank you, Lord (and Rob and Yves) for an exceptional eureka post. This has the caliber of revealed, Solomonic wisdom, clearly bringing out a halleujah choir of great thinking and resources, (with the exception of KAK, but I suppose even aimless crap-flingers serve their purpose:-). This is so compelling, despite the account balance stuff mostly above my head, the gist of it rings of self-evident truth. At some point it will be irresistible, but unfortunately it may required a large collapse to break down the casino first.

Anyway, thanks, Mr. Parenteau and thanks, Yves. Take your time resting and recovering, especially if you have guests like this to cover for you.

Several bloggers have solicited recommendations for antonyms for Austerian/Austeria, following from the root stimulus. Have you fashioned something there as well?

Yes but I won’t share it unless the blogosphere, who almost to a man assigned the origin of Austeria/Austerian Economics incorrectly to a fellow blogger, Mark Thoma, at Economist’s View, agrees to this time correctly assign attribution to me. It is only fair. Not asking for royalties here, just recognition of actual sources, which is a chronic problem in old media, and not surprisingly, magnified even more in new media.

Ok, I will give it up.

They opposite of the Austerians is…the Libertinians.

If you use it, please be smart enough not to go attributing it to someone who did not come up with it first, ok?

Not only that, but I’ll do best to enforce proper attribution on any miscreants.

Please see my 8:12 am response to David – if that does not clear things up, come back to me, ok?

PSFB has been decomposed into HFB and NBFB for many, many years. I do so in my prophetic Nov. 2006 Levy Public Policy Brief no. 88, but Godley was doing it for many years before.

Higher levels of aggregation are chosen to make the approach more accessible to people. 3 moving parts, 3 dimensions, seem to be the limit of most people’s capacity to handle models and such.

best,

Rob

Wynne Godley’s views are also at odds with the Modern Money economists. His views are more (Post) Keynesian and different from MMT.

I hadn’t seen the decomposition before this, sorry.

I’m still struggling a bit with the intuition from another perspective. Let’s just flip the terminology a bit and refer to a generic current account surplus (i.e. its a deficit when the surplus is negative, as in the case of the US). Then what you’re saying effectively is that a shift in the share of the current account surplus from non-households to households will end up increasing the surplus in total (making the surplus more positive, or a deficit less negative). If the shift in share doesn’t happen via the government, then it must happen through the business sector. And if that’s the case, it must happen through increased real investment. The net result of all that is that increased investment domestically will increase a current account surplus (reduce a deficit) and increase even more so the household surplus. So I’m just trying to get some intuition on the last sentence, which is the logical implication of your sector balances portfolio shift approach.

Why are governments suddenly talking about austerity and why do they need to do it so quickly?

Austerity = ensure that government has the ability to socialize bank losses without raising taxes (on the wealthy).

It started in eurozone because EMU means Germany and France bear the brunt of the necessary adjustment. In the US the wealthy/bankers would LOVE to follow along – making the schoolyard excuse that the others are doing it.

With millions out of work on both sides of the Atlantic, fiscal austerity is misguided and may be the new depressionary beggar-thy-neighbor. Next up: reduce unemployment benefits and lower the minimum wage. Those lazy ba*terd* need a swift kick in the a**. (side benefit on boths sides of the atlantic: no more immigration problem, hurrah!)

Yes, precisely Jackrabbit.

I believe we will find the Austerians, whether in tea party guise or neoliberal garb, are wittingly and unwittingly in some cases, just dupes for global finanzkapital.

Sock puppets is the phrase I use for politicians in their keep.

So you are barking up the right tree – and I remain surprised how few people can figure out this is the tree they need to be barking up. Really, how much more obvious could it be after the GFC and the Great Mop Up policy manuevers that followed?

Jackrabbit,

The answer to why they are in such a hurry with austerity is that they are desperate to paper over the austerity perpetrated by them in the US by Wall Street policy over the last 20-30 years when each and every leveraged merger or acquisition resulted in huge leveraged fees for the likes of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. L.P. 9 West 57th Street Suite 4200 … Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. Ltd. Stirling Square 7 Carlton Gardens London SW1Y 5AD etc., <a href="The answer to why they are in such a hurry with austerity is that they are desperate to paper over the austerity perpetrated by them in the US by Wall Street policy over the last 20-30 years when each and every leveraged merger or acquisition resulted in huge leveraged fees for the likes of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. L.P. 9 West 57th Street Suite 4200 … Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. Ltd. Stirling Square 7 Carlton Gardens London SW1Y 5AD etc., here bloated stock options and millions of ‘downsized’ people at thousands of companies , eliminated benefits, eliminated journalism, imported garbage from slave labor, off shored profits, destroyed the justice system, tore up the constitution -ITS A LONG LIST.

The austerity rush is a symptom of their panic over GAME OVER -people all over the world GET IT.

and furthermore, they want some kind of government imprimatur on austerity while people are struggling with day-to-day existence still blaming themselves, and before they become one uncontrollable reaction.

Rob Parenteau,

You’re selling sound logic, rationality and factual truth, and the neoliberals are selling a morality play, and you’re getting your ass kicked.

I certainly don’t wish to challenge the substance of what you put forth here. Your evidence and logic are unimpeachable. However, you need to stop and ask yourself why you’re doing so badly in the courtroom of public opinion.

I’m currently reading David Sloan Wilson’s Darwin’s Cathedral: Evolution, Religion and the Nature of Society, and it’s chock full of wonderful insights.

One of those is that the social sciences are all over the map in their theorizing. The anthropologists have their theories, the sociologists have theirs, the psychologists have theirs, the economists have theirs and so forth. And as Wilson concludes, “You know there is a problem when one man’s heresy is another man’s commonplace.”

The economists have erected rational choice theory as their be all and end all. As Wilson explains, it is “presented as a psychological theory that attempts to explain the length and breadth of human nature with a few axioms about how people think.” But, alas, as Wilson goes on to explain,

physics might be reducible to a few fundamental laws but not psychology. The human mind is a mélange of adaptations and spandrels that have accumulated over millions of years, during which both culture and life in groups have been integral parts of the evolutionary process. Cost-benefit reasoning is an important part of human (and animal) psychology but not the only part.

“Emotions are evolved mechanisms for motivating adaptive behavior that are far more ancient than the cognitive process typically associated with scientific thought,” Wilson continues.

The end result is that economists tend to be more prescriptive than descriptive when it comes to human behavior.

To wit, Wilson asserts, “a fictional belief system can be more motivating than a realistic one.” And look at your current situation! Doesn’t that describe it perfectly?

Amitai Etzioni in The Moral Dimension: Toward a New Economics also asserts “that commitments to moral values also affect economic activities.” And when it comes to saving behavior, he counters classical economic dogma as follows:

Neoclassical economists explain the level of saving mainly by the size of one’s income (the higher one’s income the more one saves), by the desire to provide for consumption in retirement, and by the level of interest rates. However, these factors explain only part of the variance in the amount saved. There are at least three moral values that also affect the amount saved: the extent to which one believes that it is immoral to be in debt; that one ought to save (for its own sake) and in order not to be dependent on the government or one’s children; and that one ought to help one’s children “start off in life.”

I think if you will look at some of the arguments the neoliberals are making, they are punching some of these moral buttons, applying them to nation-states.

Someone here on Naked Capitalism yesterday provided a link to this article by Michael Hudson:

http://neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com/2010/06/europes-fiscal-dystopia-new-austerity.html

To me this represents a tremendous leap forward for economists, as it finally starts addressing the moral dimension:

If the financial sector can be rescued only by cutting back social spending on Social Security, health care and education, bolstered by more privatization sell-offs, is it worth the price? To sacrifice the economy in this way would violate most peoples’ social values of equity and fairness rooted deep in Enlightenment philosophy.

The point I’m trying to make is that there is nothing wrong with empirical truth and rational thought. I’m all for that. But in order to motivate the masses, those by themselves fall short. Empirical truth and rational thought, in order to be salient and to resonate with a broader audience, must be presented within a larger moral framework.

DownSouth – Yes, as Lord Turner said at the INET inaugural conference in Cambridge, we are dealing with a cult.

I have suggested to others who advocate views similar to my own that we need to hire a cult deprogrammer to get our perspective across.

Rational discourse is hardly enough in a world where people have been trained to respond to superficial subconscious cues through years of advertising and campaigning.

If you have any contacts in this area, I am dead serious about this – send me e-mail addresses or phone numbers or books by cult deprogrammers with a very successful track record, and please do so soon.

best,

Rob

Rob,

First of all, great article, thank you!

Regarding your quest to deprogram the masses, I have a feeling you’re barking up the wrong tree. That would be tantamount to erasing our own psychological susceptibility to subliminal messages and such imprinted survival strategies as judging with the help of associations and subconsciously recorded memories. As you may be aware, Warren Mosler, a fellow Chartalist, has been testing the limits of communication and rational thought while on the stump. I don’t always agree with his terminology, but I think he is headed in the right direction in bringing his message across. Soundbites and carefully calibrated undertones are important building blocks of communication (especially for a broad audience), in my opinion. A knowledgeable person on this subject (whom you are probably aware of) is George Lakoff with his cognitive science theories on framing and moral politics.

Anyway, not sure this was helpful or in any way news to you, but I wish you well on your quest!

For those interested: in this speech Lakoff starts off with comparing morals with accounting. That should keep MMT fans entertained.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5f9R9MtkpqM

Did I just miss that great big tongue in your cheek? Maybe I’m the one who needs deprogramming…

Nice comment, DS. I’m going to pick up Wilson’s book. Sounds great.

“There is a glut of profits, and these profits are not being reinvested in tangible plant and equipment. Companies, ostensibly under the guise of maximizing shareholder value, would much rather pay their inside looters in management handsome bonuses, or pay out special dividends to their shareholders, or play casino games with all sorts of financial engineering thrown into obfuscate the nature of their financial speculation, than fulfill the traditional roles of capitalist, which is to use profits as both a signal to invest in expanding the productive capital stock, as well as a source of financing the widening and upgrading of productive plant and equipment.”

Well, this is COMMONPLACE for everybody… or it is?

A CEO who plans to work, let’s say, five years for a company and is paid for performance, possibly with a lot of stock options, would be a FOOL or an IDEALIST to spend a dime in “upgrading of productive plant” or similar amenities.

He wouldn’t be hired in the first place.

I work for what used to be a famous US “high-tech” company.

In the last 10 years, 90% of sites both in US and UE have been shut down, 90% of R&D has been wiped off, most production has been outsourced in China, some in Malaysia, and as a consequence we are now quite profitable, we are doing great on NASDAQ, and our CEO has become VERY well off.

So, here are my equations: to get high earnings (E) and a high share trading price (S) you need to keep downsizing the company (C) firing people, closing plants, closing R&D…

Something like:

δE/δt = -K δC/δt

δS/δt = -J δC/δt

(where K and J are empirical constants and t is time)

In the long run, some dependence of K and J from C (i.e. the actual size of the company) might lead E and S to decrease, even to vanish, but if you are smart you won’t be anywhere near at that time…

PDC – Agreed, we get what we pay for. If we want to pay management to play, they will play casino games. If we want to pay managers to reinvest profits in tangible capital assets, we need to change their incentive structures, and the incentive structures faced by their investors who heretofore have been happy to let them loot and speculate in the name, paradoxically, of honoring “shareholder value maximization”.

Strange world indeed. Glad you can see through the lies and distortions.

best,

Rob

“Turns out it is a corporate savings glut. There is a glut of profits, and these profits are not being reinvested in tangible plant and equipment.”

Why is the question and the three provided by the author are only part of the story. There are other structural factors/imbalances at work. MGI [McKinsey Global Insight] suggested in a series of studies a few years back that the “baby boomer” population explosion so distorted “aggregate demand” after WW II that as they die off, said demand in Western countries will decrease or return to “normal” historical levels – that there will be a glut of housing, etc. With birth rates falling below the replacement rate in some of these countries, there will also be “labor shortages” absent significant immigration along with the political turmoil it engenders with consequences for pension obligations, etc. Major corporations have concluded rightly, assuming MGI’s analysis is accurate, that investment in plant and equipment in the capitalist core countries is not required as their will be “excess capacity” across the board for years to come. Consequently, what additional investment in plant and investment there is is likely to be capital-intensive and labor saving, exacerbating unemployment with its downward pressure on both wages and aggregate demand and their impact on government deficits. Increasing taxes on these same corporations for not investing in plant and equipment when it isn’t needed is likely to be resisted and counterproductive. Capital is on STRIKE for a number of reasons. It is “simply” adjusting supply to meet forecasts of decreased demand in the United States and Western Europe.

While this absolute ability to produce goods and services is no longer in doubt, there is a mismatch between this postscarcity of goods/services and the growing “scarcity” of gainful employment – the means to consume/purchase these goods/services – in the West and Japan with the consequences mentioned previously. The fact that the production of many of these goods occurs offshore in low-wage countries only exacerbates this problem. “Technological unemployment” is not a topic for discussion by most economists, regardless of their other differences. Yet with unemployment and underemployment approaching 20% in many of these countries, the “scarcity” of gainful employment amidst a postscarcity of goods and services – excess capacity – will not be resolved without serious consideration of this subject. It is a downward deflationary spiral with decreases in aggregate demand fostering little investment. if any, in additional plant and equipment with an increase in unemployment resulting in a further decrease in demand… and deficits, making the AUSTERITZATION of consumption – public and private – appear a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This structural imbalance absent “full employment” policies isn’t even considered and signifies the triumph of Austerian economics among ruling elites in this country over the course of the past 40 years and elsewhere as well. Unemployment levels reached their lowest level in the entire post-WW II era during the late 60s and early 70s. Ever since they have steadily increased in a “ratchet effect” with each successive recession giving rise to the notion of “jobless recovery”. Low unemployment gives LABOR a distinct advantage vis-à-vis CAPITAL in such a situation, whether organized or not, and accounts for the labor militancy witnessed during the late 60s and early 70s in this country and Western Europe. It was not uncommon back then to quit one’s job in one rubber company, steel company, or auto company and find a job in another one the same day in NE Ohio. This situation was not lost on employers or policy makers. Combined with the subsequent downsizing of manufacturing and its offshoring, this “offensive” by capital has destroyed the blue-collar manufacturing base of the Democratic Party and impressed upon workers just how important steady employment is. It’s no coincidence that strikes and other forms of labor militancy have steadily decreased during this period as well. High levels of unemployment and the uncertainty it generates provide capital a distinct advantage in this context and make fiscal austerity even more likely. Witness the recent failure of the extension of unemployment benefits because of deficit concerns..

When seen in this light, fiscal AUSTERIA is merely a continuation of the AUSTERITY that began three decades ago with policies that made higher levels of unemployment acceptable. It signified a decisive policy shift away from full employment and a growing reliance on debt to offset deficits, both public and private. Yet it doesn’t even show up on the radar screen as AUSTERITY. “Solarization” has to be seen in this light and merely as a first step in redressing this growing structural imbalance between the postscarcity of good/services and the “scarcity” of jobs that make for their consumption. Full employment renders fiscal austerity a moot issue as both aggregate demand and government tax receipts will increase across the board, perhaps even allowing for deficit reduction over time. That much I think Mr. Parenteau would agree with. MMT adherent’s have to couple their anti-austeria broadsides with “full employment” as a counterweight to AUSTERITY to gain any political traction. Employment is straightforward and something that resonates with the average American. Having a job, not having one, or the threat of not having one bears directly on how the issue of fiscal austerity is perceived regardless of what MMT might have to say about deficits.

Agreed Mickey, which is why I have encouraged advocates of MMT views to lead with an employer of last resort/job guarantee argument, rather than more abstract monetary economic principles, when they state their case in public forums. I think some of them are getting this and adjusting their message accordingly. See Mosler’s Senate campaign in Connecticut for example.

best,

Rob

If they lead with ELR, they should follow with the zero rate, zero bond proposal. That’s the only way the monetary piece has any bite. Otherwise, they’re no different than Krugman in the monetary part of the messaging.

gotta agree.

Mickey Marzick in Akron, Ohio,

I would just add that there is a moral component to be found here also, because labor is good. Work is good.

We have Marx to thank for this, as Hannah Arendt explains:

The really anti-traditional and unprecedented side of his [Marx’s] thought is his glorification of labor, and his reinterpretation of the class—-the working class—-that philosophy since its beginning had always despised. Labor, the human activity of this class, was deemed so irrelevant that philosophy had not even bothered to interpret and understand it.

[….]

Labor is necessarily prior to any economy, which is to say that the organized attempt of men living together, handling and securing both the needs and the luxuries of life, starts with and requires labor even when its economy has been developed to the highest degree. As the elementary activity necessary for the mere conservation of life, labor had always been thought of as a curse, in the sense that it made life hard, preventing it from ever becoming easy and thereby distinguishing it from the lives of the Olympian gods. That human life is not easy is only another way of saying that in its most elementary aspect it is subject to necessity, that it is not and never can become free from coercion, for coercion is first felt in the peculiarly all-overwhelming urges of our bodies. People who do nothing but cater to these elementary coercive needs were traditionally deemed unfree by definition—-that is, they were considered unready to exercise the functions of free citizens. Therefore those who did this work for others in order to free them from fulfilling the necessities of life themselves were known as slaves.

[….]

Marx is the only thinker of the nineteenth century who took its central event, the emancipation of the working class, seriously in philosophic terms. Marx’s great influence today is still due to this one fact…

[….]