Yves here. Normally I put up cross posts without additional commentary, but I wanted to offer a couple of observations about this post. While this piece is admittedly a bit heavy on economist-speak, and readers may differ with the policy recommendations, = it gives an even-handed account of the early rebound during the Great Depression and the backtracking in 1937. Since we have few examples of severe financial crises in large economies, let alone global financial crises, the Great Depression remains an important case study.

By Nicholas Crafts. Professor of Economics and Economic History at the University of Warwick and CEP, and Peter Fearon, Professor Emeritus of Modern Economic and Social History, University of Leicester. Cross Posted from VoxEU

OECD countries are recovering from the worst recession and financial crisis since the Great Depression. Policymakers’ problems are now those of designing the right exit strategy. Withdraw stimulus too soon and tip the economy back into recession; leave it too late and see inflation take off.

While interest rates are at or near the lower bound, fiscal multipliers are probably high. Yet in the medium term, fiscal sustainability needs to be restored at a time when structural budget deficits have been raised by the adverse impact of the banking crisis on potential output.

In this context, it is timely to revisit the severe recession that rudely interrupted the strong US recovery from the depression in 1937/8. This episode is relatively little-known to most non-US economists but offers lessons that we should heed. A recent paper by Francois Velde (2009) provides an excellent description and analysis.

The recovery from the Great Depression

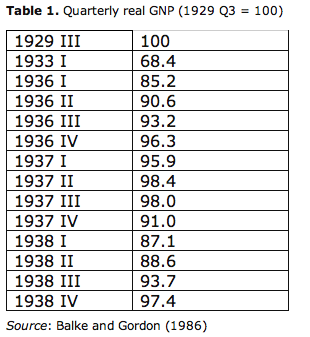

Recovery from the depression was vigorous in the years after 1933. Table 1 shows that by 1937 real GNP was nearly back to its peak and more than 40% higher than the nadir of the depression in early 1933. It is generally agreed that the recovery was largely a result of the new policy regime established when the US left the gold standard in March 1933. As Christina Romer pointed out, this was followed by very strong growth in the money supply (Romer 1991, 2009). Crucially, the new regime meant a return to inflationary expectations which Gauti Eggertsson’s DSGE model sees as fundamental to an escape from the liquidity trap (Eggertsson and Pugsley 2006, Eggertsson 2008). Both authors make the point that, with nominal interest rates near the lower bound, Roosevelt’s strategy of seeking to return prices to mid-1920s levels represented a route to the dramatically lower real interest rates which were central to the transmission mechanism. Although federal government expenditure rose sharply, as is very well-known to economic historians, the New Deal was at most a very modest fiscal stimulus but it may have contributed to changing inflationary expectations. Budget deficits of 3% or 4% of GDP reflected the weakness of tax revenues in years of weak economic activity.

In early 1937, there was still an output gap, estimated by Balke and Gordon (1986) to be around 15% of GNP, but there was a widespread feeling that the depression was over. The focus of policymakers was shifting to concerns about future inflation and a return to a balanced budget. The Federal Reserve was worried by the build up of substantial excess reserves in the banking system while on the fiscal side the ratio of the national debt to GDP had risen from 16% in 1929 to 40% by 1937.

The Federal budget was returned close to balance in 1938 following increases in income tax rates in 1936, and the introduction of social security taxation from January 1937. There was also a cut in spending from a 1936 spike caused by a one-off payment of Veteran’s Bonus. The implication was a discretionary fiscal tightening amounting to over 3% of GDP, according to estimates by Larry Peppers (1973). On the monetary side, a new policy of sterilising gold inflows was adopted in December 1936 and reserve requirements for the banks were doubled in three stages from August 1936 through May 1937. The Federal Reserve Bank’s rhetoric changed to highlighting dangers of inflation. An analysis by Velde (2009) suggests that these policy changes were sufficient largely to explain the recession which NBER dates as running from May 1937 to June 1938. As can be seen in Table 1, there was a steep decline in real GNP which fell by about 11%. Industrial production was down by over 30% and investment by over 50% while share prices declined by over 40%. Inflation ceased and prices started to fall again. This was a big reversal and the contraction in economic activity was at similar rates to the early 1930s.

The recession ended when reserve requirements were eased, gold sterilisation ceased, and the balanced-budget policy was dropped as government spending was increased by $2 billion.

It is reasonable to suppose that the fiscal multiplier is quite high when interest rates are low and there is less scope for crowding out, as is confirmed by the review of theory and evidence provided by Robert Hall (2009). This was probably true in the late 1930s as Robert Gordon and Robert Krenn’s estimate of a multiplier of 1.8 in 1940 suggest (Gordon and Krenn 2010). If fiscal consolidation was to be attempted, then expansionary monetary policy was needed to compensate for its deflationary impact. Instead, the American economy was hit with a double whammy. An important aspect of the changes in policy stance in 1936/7 was the impact through undermining inflationary expectations with the implication that real interest rates rose steeply according to Romer. Eggertsson and Pugsley (2006) find that quite small changes in public beliefs about the government’s future inflation target would have had significant effects on output with nominal interest rates abnormally low.

Key message for today’s policymakers

The key message here for policymaking in the current situation is not that fiscal consolidation should be postponed. Rather, it is that exit strategy needs to focus on providing monetary support for aggregate demand as fiscal stimulus is withdrawn.

This has been a feature of successful fiscal consolidation efforts in OECD economies in recent times when interest rate cuts have been part of the overall package. Now, as in the 1930s, there is no scope to cut nominal interest rates. The requirement then is to operate on real interest rates and to seek to embed expectations that prices will rise. This suggests that further quantitative easing may be appropriate and that thought should be given to suspending inflation targets in favour of price level targets.

In the recent crisis, we believe that the aggressive response made by US and other policymakers was a massive improvement compared with the catastrophic errors made in the early 1930s. Accordingly, we have gone through a Great Recession rather than a re-run of the Great Depression. Important lessons from economic history relating to containing the downturn have been well-learnt. However, the 1930s has more to offer in terms of relevant experience for today with regard to managing the recovery. Those who would like to learn more can turn to our survey paper written as an introduction to a collection of articles which seek to bring the lessons of the 1930s from the specialist literature to a wide audience (Crafts and Fearon 2010).

Analogy: “form of reasoning in which one thing is inferred to be similar to another thing in a certain respect, on the basis of the known similarity between the things in other respects.”

This kind of reasoning that we read again and again on US blogs and media, Krugman springing to mind…, that compare the US of 30s with the current version.

What a stupid analogy and and dubious logic. pre-WWII US were an industrious and thrifty people, à la chinoise.

Of course you can have a liberal agenda on this blog. Come on. These discussion are so passé. And in denial of the current US reality. That now bears more resemblance with 1873 Austria than 1929-1936-US.

China is now the industrial and thrifty people on the planet. Sure we be glad to hear about a US renaissance but certainly not in the way current US liberal do consider it. It can only be a costly and painful reconstruction. No a one-shot-influx will solve anything. “The writing on the wall” anyway.

Concerning the 1873

http://chrissnively.wordpress.com/2009/05/09/grunderkrach-may-9-1873/

Daniel de Paris said: “These discussion are so passé. And in denial of the current US reality. That now bears more resemblance with 1873 Austria than 1929-1936-US.”

Good grief! Can someone spare us these vapid inanities emanating from the Austrian School? How did we arrive at such a state where such intellectually and morally bankrupt nonsense can gain credence?

Here’s how Hannah Arendt explains it:

At any rate, the result of the ‘American’ aversion from conceptual thought has been that the interpretation of American history, ever since Tocqueville, succumbed to theories whose roots of experience lay elsewhere, until in our own century this country has shown a deplorable inclination to succumb to and to magnify almost every fad and humbug which the disintegration not of the West but of the European political and social fabric after the First World War has brought into intellectual prominence. The strange magnification and, sometimes, distortion of a host of pseudo-scientific nonsense—-particularly in the social and psychological sciences—-may be due to the fact that these theories, once they had crossed the Atlantic, lost their basis of reality and with it all limitations through common sense. But the reason America has shown such ready receptivity to far-fetched ideas and grotesque notions may simply be that the human mind stands in need of concepts if it is to function at all; hence it will accept almost anything whenever its foremost tasks, the comprehensive understanding of reality and the coming of terms with it, is in danger of being compromised.

–Hannah Arendt, On Revolution

And 1873! Of all dates! That is the same year “the Crime of ’73”—-the Fourth Coinage Act—-was perpetrated on the American people by the banksters. The Fourth Coinage Act was enacted by the United States Congress in 1873 and embraced the gold standard and demonetized silver. It was a move that contracted an already scarce money supply even further.

The banksters’ motive for urging a gold-standard upon the American people was greed, pure and simple. The reasons are outlined by Lawrence Goodwyn in The Populist Moment:

However, bankers and other creditor-bondholders had a more specific motive for specie resumption. The currency had depreciated steadily during the war, and, having purchased government bonds then, they, understandably, looked forward to the windfall profits to be made from redeeming their holdings in god valued at the pre-war level. A government decision to begin paying coin for its obligations would mean that, though the Civil War had been fought with fifty-cent dollars, the cost would be paid in one-hundred-cent dollars. The nation’s taxpayers would pay the difference to the banking community holding the bonds…

Some practical difficulties intruded, however. A return to hard money could only be accomplished in one of two ways—-both quite harmful to a great number of Americans. The first was to raise taxes and then employ the proceeds to redeem wartime bonds and to retire greenbacks from circulation. This, of course, would contract the currency abruptly, driving prices down, but also depressing business severely and increasing unemployment, perhaps to socially dangerous levels…

The second method of contracting the currency spread the resulting economic pain over a longer period of time. The government could merely hold the supply of money at existing levels while the population and the economy of the nation expanded, thus forcing general price levels down to a point where it was no longer profitable to redeem paper dollars in gold to finance imports. In due course this is what happened.

[….]

After a measure of hesitancy by business and labor greenbackers, the amount of currency in circulation was held at a stable level through the decade of the 1870’s while expanded population and production reduced price levels and spread sever economic hardship throughout the nation’s agricultural districts. Hard-hit farmers were brusquely told they were guilty of “overproduction.” The economic depression was both protracted and severe. Business was badly hurt and unemployment rose, but by the end of the decade the goal was reached: the United States went back on the gold standard on January 2, 1879.

There’s a vivid explanation of the 1860-1910 period on this video (I think it was Paul Repstock who furnished the link) beginning at minute 40:00 and running through minute 1:10:00. It exposes the behind-the-scenes machinations of the banksters and puts them in historical context. I found the actual quotes from various internal memos of the American Bankers’ Association, explaining how they intended to manipulate and exploit the “inferior social stratum of society,” to be most revealing of the sort of sociopaths we are dealing with.

That is a great reference, thanks.

Farmers were guilty of “over-production” and the rest of the public was guilty of “over-hunger”.

Powerful stuff Down South, especially relating to conceptual level thinking being lost. I have a feeling you will like this graph on this article I wrote. Every time in history equality is being pushed much harder than liberty, watch out! A population is getting looted. http://ragingdebate.com/politics/feeling-upset-because-the-american-population-wont-wake-up-as-the-us-falls-apart

Gold sterilization — circa 1937.

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,762357,00.html

Yves, you left out the authors’ references. No doubt you had your reasons. But some are worth consulting. Here they are. They are not all in econo-speak.

Balke, N and RJ Gordon (1986), “Appendix B: Historical Data”, in RJ Gordon (ed.), The American Business Cycle: Continuity and Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 781-850.

Crafts, N and P Fearon (2010), “Lessons from the 1930s’ Great Depression”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 26:285-317.

Eggertsson, GB (2008), “Great Expectations and the End of the Depression”, American Economic Review, 98:1476-1516.

Eggertsson, GB and B Pugsley (2006), “The Mistake of 1937: a General Equilibrium Analysis”, Monetary and Economic Studies, December, 151-190.

Gordon, RJ and R Krenn (2010), “The End of the Great Depression, 1939-41: Policy Contributions and Fiscal Multipliers”, NBER Working Paper 16380.

Hall, RE (2009), “By How Much Does GDP Rise if the Government Buys More Output?”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, 183-231.

Peppers, LC (1973), “Full-Employment Surplus Analysis and Structural Change: the 1930s”, Explorations in Economic History, 10:197-210.

Romer, CD (1992), “What Ended the Great Depression?”, Journal of Economic History, 52:757-784.

Romer, CD (2009), “The lessons of 1937”, The Economist, 18 June.

Velde, FR (2009), “The Recession of 1937 – a Cautionary Tale”, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Economic Perspectives, Quarter 4, 16-37.

I always leave them out on VoxEU pieces, they take up real estate. The piece clearly is footnoted, and I provide the link, so the rigorous/studious can readily find them.

Occam’s Razor: Since the end of the nineteenth century the average length of recovery between periods of recession was about four years. Length of time between 1933 and 1937, about four years. Conclusion: economic growth cycles reverting to the mean. Finis. Lessen for today’s policy makers: do nothing and let market forces reallocate labor and capital to better uses.

Unfortunately we are more likely to understand the Great Depression better when we understand the Great Recession, instead of the other way around. Our conventional history of the Great Depression is deeply flawed.

After 1933 the federal government was stimulating the economy by providing jobs. The Civilian Conservation Corp was created in 1933 and it employed 250,000 young men that year. (Most of their pay was sent to their parents.) In 1936 there were 350,000 men in the CCC. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civilian_Conservation_Corps) The Works Progess Administration was created in 1933 with plans to employ 50% of the 7,0000,000 eligible people. It employed 3.55 million in 1938 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Works_Progress_Administration)

Before the Great Depression the USA had been a net exporter. GDP had to drop significantly as the Great Depression spread around the world. How much of the GDP reduction by 1933 was caused by the reduction in exports? What was the yearly recovery of exports between 1933 and 1940? I suspect the answer is that exports had not recovered to any significant degree.

In 1937 the new Social Security withholding tax was taking 1% of employees pay. (Employers paid nothing.) Did this reduction in net pay inordinately affect employees spending?

A Veterans’ Bonus had been paid out in 1936. ($1.5Billion was paid out to 4,000,000 veterans.) This was a stimulus to the economy but it was a temporary shot.

The truth is that the economy had not recovered by 1937, the illusion of health was artificially induced. So when they tightened the money supply, unemployment rose 5%. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recession_of_1937–1938)

The Federal government has been spending huge sums into the economy for stimulus since 2008. In addition they have bailed out the banks with huge sums of money. All of this has served to mask the problems in our economy and they have declared the recession has ended, even though unemployment has not been reduced.

Generally speaking, there is something in our psycological makeup that requires us to find the positive in our terrible situations. That flaw is apparent now, and it would have been apparent in 1937 to those who chose to look.

“However, the 1930s has more to offer in terms of relevant experience for today with regard to managing the recovery. “

The conventional wisdom is that the Great Depression ended when World War II began. Thus the stimulus provided the the Civilian Conservation Corp and the Works Progress Administration was replaced by the USA increasing the size of it’s military and increasing the industrial capacity to produce war materials. At this point you should be thinking that the conventional wisdom is a little absurd. That was still government spending. How can the production of war materials, which would be destroyed in short order, represent recovery?

My explanation is that 8 million men were enlisted or drafted in the military during WWII and a large percentage of those were sent into war zones where there was little or no opportunity to spend their pay. That unspent money was sent home to save. Also the war effort required many women to work in factories producing war material but they could not spend their money either. ‘Rationing’ limited purchases of sugar, gas, tires and many other items. Few if any automobiles were produced for sale to the public in 1942, 1943, 1944, and 1945. American workers put large percentages of their income into war bonds. Saving rates reached 25% and by the end of the war there were large pent up savings. When the war ended large numbers of those military men came home, started a family, and bought durable consumer goods. Factories had to hire employees and those employees also wanted durable consumer goods. There was the regenerative effect that ended the Great Depression!

But what was the source of the income which Americans saved during WWII? Taxes had been greatly increased. The richest were paying Federal taxes of 94%, up from 66% in 1940. Those with incomes over $8000 saw that Federal tax rate go from 12% to 25%. And the Federal government ran up deficits by borrowing from those savers who bought War bonds. Those bonds were redeemed after the war when presumably the government spending had been dramatically reduced but the tax rates were still high.

So the recovery from the Great Depression occurred after 1945 which means that it took about 16 years.

I don’t see any of this as a path to recovery from our Great Recession.

The article says that in the depths of the Depression (with tax revenues down and the New Deal’s spending in full sway), we were running deficits of only 3-4% of GDP. Whole different kettle of fish from present day USA, and one of the main reasons why the whole “spend and print” approach to today’s situation is as useful as another tool used in our distant past, the buggy whip.

While there may be a lesson to be learned from 1937-1938 I’m not sure what it is. Throwing more money – Quantitative Easing III coupled with “fiscal consolidation [AUSTERITY-LIGHT] – isn’t likely to solve anything, but merely prolong the Great Recession. Besides anyone who grocery shops knows that one is already buying LESS for the same price – INFLATION – not reflected in the CPI. So we’re already cognizant of “rising” price levels. Hyperinflation is not a solution, especially if one is a creditor. And mainstream economists are concerned primarily with the fortunes of the latter, not debtors.

But where are the “animal spirits” for investment? What is the “new” engine of growth/gainful employment in this country? Unlike 1937-38, the housing-automobile-suburbanization POSTWAR boom has run its course. “Greening” America is touted as such an engine but I have my doubts. Too many entrenched interests dependent on fossil fuels to switch from green money to green energy. Health care/medicine? What’s the point of extending life expectancy when the “elderly” are increasingly deemed a burden to society? Moreover, who wants to retire into poverty? And if I work longer because I can’t retire, how will a younger person find gainful employment? Perhaps it’s just a numbers game and waiting until the “baby boomers” die off. Then more natural, historical trends will kick in and all will be well.

No, even “growth” itself is in question. Increasing efficiencies – in both energy and labor – do not yield gains in employment sufficient to offset each other with the result that aggregate demand suffers because stagnant wages do not allow for ever growing consumption. In this respect, neither Keynesianism nor neoliberalism are adequate to the extent that they are predicated on growth in the “real economy”. For it’s the latter that has stalled out, choking on “excess capacity”. Nor does additional “financial innovation” intended to devise ever newer ways of cutting, slicing, and dicing credit to stimulate consumption appear in the offing. Only if one accepts debt peonage as a way of life will this work. But even then, “creditors” are likely to be a bit more circumspect to whom they extend credit as the risk of default increases. A warehouse full of repossessed flat screen TVs, a lot of repo’d autombilies, or ownership of empty, foreclosed houses with no buyers in sight does not make for a growing economy, even if it constitutes “financial innovation”. So economic expansion predicated on the credit spigot would appear to have run its course as well.

Companies have already factored much if this into their “strategic thinking”, cutting productive capacity in anticipation of flat demand for the foreseeable future and reducing employment to the minimum, learning how to do more with less. There is a difference between being “laid off” and “RIFfed”. The former implies that your old job might be waiting for you if the economy picks up whereas the latter means it’s time to find a new career. Most of us will have to adapt to the latter in what will likely be another “jobless recovery”. Oh, I forgot the Great Recession is already officially over.

Perhaps a mandatory reduction in the work week and acknowledgment of “technological unemployment” might provide the means with which to address some of these structural problems, but in the current political environment where the unemployed are vilified as “slackers” neither seems likely. Short of “debt peonage” in an economy with much reduced aggregate demand where “supply begets its own demand” [an iron heeled AUSTERITY] or a massive die off in which much plant and equipment are also destroyed – WWIII? – whatever the lesson of 1937-38, neither of these is worth learning a second time. This time is different, right?

Mickey, you have it exactly right. America has been abandoned by a greedy mendacious bamboozling elite. All academic solutions are premised on otherworldly assumptions. What we have is consumption without production. What we consume is errant nonsense and shit that begins falling apart before you finish dragging it home. Survivors will be those who hunker down to individual solutions and ignore the smoke and noise. Climate change will soon make all of this irrelevant, perhaps within a decade. Welcome to the age of ENTROPY.

Entropy nonsense. Ever notice that every time “THE END” comes, there’s still something else after it? One thing ends, another comes into existence. “We” may not get through it okay, but there will still be some sort of “We” on the other side of whatever it is we fear.

Very well said Mr. Marzik!

I particularly liked your comment on ‘technological unemployment’, and how certain entrenched interests would derail the evolution of the American economy from ‘green money to green energy’. I would summarize, that america, although it has the knowledege , Capitol base, and the resources, lacks the political will to override the entrenched interests and transition the economy from doing useless things (like building large houses, building military weapons, bailing out speculation fiascos courtesy of our casino bankers ) to longterm useful things like green energy, environmental/soil remediation, ocean clean- up and habitat cultivation ( so we can safetly eat the tuna, and have more tuna) . And we all know from MMT theory that the federal government does not lack the money, afterall if the Federal reserve can print trillions of dollars to bailout bankers (and banker bonuses world wide), the Federal reserve can print

money to facillitate useful work for the peope of the America.

Second the motion on Mr. Marzik’s cogent analysis and yours as well Mr. Ming.

The will to conduct production will come from the investment community that has been used to index investing and highly predictable returns to one of no growth.

That causes pain and the pain creates the incentive for the investment community to invest in political change. I see that in 2013 as the beginning. Can the American and Chinese people keep a lid on our inept current leadership blowing one another up to misdirect ourselves from the harsh but temporary pain? Let’s hope to God we can.

One major difference between the great depression and the great recession was the faster destruction of credit in the former as opposed to the latter. The total debt/GDP ratio was 200% in 1930 and dropped to roughly its historic norm of about 65% by 1933. Our current debt/GDP ratio is in the range of 380%, almost twice as during the great depression. Our current fiscal policy is to preserve that debt at all cost (ie prevent monetary deflation), in part by moving it from the private to the public sector (huge mistake as this will threaten survival of the government itself) and in part through money printing (another huge mistake because it will fuel price inflation causing social unrest of the increasing population of poor). At some point, the majority of that debt MUST be written off because we simply can’t service it. That would require resolution of the TBTF. It’s not a question of if, its a question of how and when.

what you say seems right to me. the only way to pay off this debt is through earnings — either by increasing exports or increasing internal demand. what do we have to export that isn’t being rapidly off-shored? I suppose a few things, but enough? Maybe some will come back if the dollar falls?

And internal demand, that’s a real chicken/egg situation that I think defies any rational quantitative analysis in the form of continuous mathematical functions.

It’s a really a jump cut, like movie editing or probability waves, where Imagination, Capital and Opportunity have to coalesce into demand possibility.

Consider that the army of unemployed could have their own country and could work for each other as everything from laborers to professors of advanced theoretical physics to doctors to architects. But they’re atomized as islands without the possibility of forming those connections, other than through riding on a larger prosperity wave, which they do not control.

It’s intersting to conceive of how many people one needs for a sane and prosperous economy founded on mutual servicing of each other’s human needs and one that can also sustain imagination leaps in the form of science and innovation, and what kind of capital formation structures such as society would need.

There’s a lot of history now to look at here, a lot of empirical evidence, that could serve to nourish a form of modest utopian theorizing about ideal economic social structures. a new political economy, as it were. Not one based on merely chronicling what has been, but on devising what could be based on the errors of the past.

craazyman, the movement of factories overseas was due to the huge pay differential between american and asian workers. That gap is slowly closing, but we won’t have factories move back until it is more profitable to do so than keeping them where they are. The chinese workers are unionizing which will help and american workers are being forced to accept less pay, but it will take several years before corporations invest back into america. Keep in mind too that we have the most stringent environmental and labor laws that corporations have to consider.

All this means is that earning in the private sector won’t expand for a long time. The government has filled this gap in the GDP by deficit spending, but the Fed is having to buy that debt because the private sector will not. The primary dealers (TBTF banks) buy the bonds from Uncle Sam and sell them to the Feds for a profit. They take those profits and invest them in the stock market taking advantage of high frequency trading (since they are physically closest to the exchanges) or buy commodities and drive up prices for the rest of us. It’s Bernanke’s hope that people will compel consumers to get ahead of price inflattion by spending their money today, which should stimulate job creation to offset the increased demand. Unfortunately, companies are simply putting greater pressure on existing workers since hiring new workers is so expensive, especially when considering employer costs of social security and medicare taxes and healthcare. Companies will put pressure on current workers until they explode. Ask your friends who work for large corporations if they’re working longer hours.

My suggestion to you is to study libertarianism. I hung slightly to the left of the political spectrum until i started reading Mises works. His writing is unfortuanetly very difficult to get through, but he nails it in my opinion. It’s the libertarians who understand what’s going on and what the solution is. The only reason our government doesn’t like it is because it would reverse the movement of the country towards fascism (where government is largely controlled or in league with large corporations).

There is a very large class warfare going on right now, and as Warren Buffet famously said, his side is winning.

fromthedeepersouth,

But what does libertarianism have to say about “class warfare”, if anything? Class warfare doesn’t exist in the libertarian worldview does it?

How do you “control” large multinational corporations with global reach with LESS government?

What is the libertarian solution? The real one – not some pie in the sky mush dependent on voluntarism and cooperation. A real solution? What does Ludwig von Mises have to say?

Mickey,

To the libertarian, as I see it, class warfare is taken care of if government is doing what it should be doing, and that is protecting the fruits of one’s labors and their basic civil rights from the predatory behavior of others. BUT, predatory behavior is what we currently have, which is why class distinctions have become so large. For example, the farm bill contains subsidies for farmers, but only the 20% or so largest farms!! I know because i work in agriculture. The “theory” is that they are critical to national security because they keep our food supply stable. In reality, they’ve destroyed family farms because the government keeps them in business, while family farms have been allowed to die. Same with banks. The small and some regional banks are being allowed to go under, while the TBTF banks are being bailed out with YOUR tax dollars. The government is NOT doing its job. If the Fed did not feed the primary dealers, they would not be loaded with extra money to stoke the stock market, making the rich richer. In fact, the vast majority of billionares are making their money in the financial sector (google it!!), but that is solely because of their exclusive position that the government has created for them. If the government would protect YOUR wealth, ie by not printing money that is used to keep the TBTF solvent but increases prices at the supermarket, you’d be in a stronger financial position to invest in the stock market, start your own business, buy nicer goods etc.

I DO diverge from libertarians on the issue of taxes where i tend to side with the father of modern capitalism, Adam Smith. Smith like you worried about wealth stratification. His argument was that if the role of government is to protect private wealth (that’s accumulated honestly), and since the cost of the protection rises with wealth, then the rich should pay more taxes than eveyrone else. In other words, the rich tend to use the courts more, have more to lose if a country is invaded by a foreign power, and certainly require greater property protection by law enforcement, so they should pay more tax to fund it. But as Warren Buffet pointed out, the rich are winning the class warfare because the tax code favors them through write-offs, deductions, etc. Here is another case where the government is failing us.

On the issue of large multinational corporations, they simply don’t need to be controlled. The vast majority of corporations end up failing because their business models usually do not adjust to changing economic conditions. Look at GM…it failed. Look at Sears, the Walmart of the late 1800s and early 1900s, its a shadow of its former self. Look at GE, on the verge of bankruptcy because they foolishly got invovled in the loan sharking business. Economics cycles on many levels, and multinational corporations are no different. However, no corporation should be allowed to have a monopoly because they will use that monopoly power to parasitize wealth that you garner honestly. That’s why we have laws limiting monopolies. But here again, our government is failing us by not enforcing those laws. Gold and silver, for exmaple, are being heavily manipulated by the big banks. Unfortunately, this is being done with a wink and a nod by the Federal Reserve because those precious metals are borometers of our currency. This is an example of how government is failing us by not only enforcing monopoly laws, by aiding and abetting them.

The solution is not voluntarism or cooperation. Quite the contrary. Libertarianism starts with the basic assumption that we all do what we do because its in our own self interest to do it. Humans are selfish by nature. On the surface that may appear bad, but look at it this way. If you are allowed to keep the majority of the wealth you earn through your efforts (work), what would you do with it? Well, you might buy a friend dinner, you might start a business, you might buy a car, you might get your teeth whitened. The best person to consider how to spend your money is YOU. Does the government waste a lot of money? Does the government take money from you and give to people not working or people who have more than they’ve truly earned or need? Would you give your money to someone extremely wealthy? Not voluntarily!! Would you give money to someone poor who hasn’t eaten for 2 days? I’ll bet you would!! and why would you? because it would make you feel good, a selfish motive, and yet, a very good motive. You see, we may be selfish by nature, but we are also compassionate and we also realize we need each other to survive, we are social creatures. So when we reach out to others, we are really creating bonds we may need in the future when we’re struggling. Our actions here are both compassionate and selfish. But in reality, that is what should be happening. Life is a give and take and the individual should decide it, not the government. The government is controlled by large corporations who are taking YOUR money and buying nice houses in south Florida…….

Absolutely!

Not great, but long…as in The Long Recession. That’s how it feels like it for millions.

Actually, it’s the Long And Great Recession.

Hi Yves…here is an article explaining to the Iris people how they are being taken for a ride by the IMF and EU….no bankers or bondholders to take a haircut instead the working people to get their wages cut etc. Care to comment or place something on your blog…we all know that this is why our government will be up to in 2011…http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/opinion/2010/1123/1224283932871.html

Thanks for the link and couldn’t even think of a news paper in Amerika that would do this. All is lost.

The important change in the Depression was in the nature and object of regulation. In the early years, Roosevelt pursued the same policies as Hoover, which were to encourage price fixing and wage fixing. The result was equilibrium at high levels of unemployment and low levels of capacity utilization. In 1937 onwards, the Roosevelt Administration changed course radically, and started trust busting and ended the policy of favoring unionization.

The result was essentially an IMF style program, and it worked. The economy restarted long before WWII and rearmament.

You cannot understand how this stuff works if all you focus on is deficit spending. This is not the only thing driving the situation. The other thing driving it is policy.

In Europe at the moment we have colossal waste and positive impediment to productivity and any sort of productive activity by the public sector. If this is not dismantled, no amount of deficit spending will help. Our problem is not spending. Our problem is an out of control public sector. If you don’t fix this, we too will enter equilibrium at high rates of unemployment and low rates of capacity utilization. Until a man on a white horse comes along.

Our problem is the majority of wealth in too few hands….when the wealth was more evenly distributed, more was spent and everyone had a fair standard of living….why should government wages not mirror the wages and benefits not mirror that of the middle class when the middle class sustained the best standard of living for all….your statements show your bias in not asking executives to take the same cuts you want others to take…..oh and by the way it is important to remember that top excecutives are really NOT that productive relative to their costs to corporations…..

But trust-busting actually should have the effect of reducing top executive pay. One of many reasons we should be engaging in more trust-busting right now (of the TBTF’s, the Big 4 accounting firms, etc.)

And thus, the beginning of decades of the the great illusion of prosperity with new money printed out of thin. What happens when it all falls down?