As readers may recall, the American Securitization Forum came out, in what it no doubt thought was guns-a-blazing style, to attack critics of securitization abuses. In particular, the ASF was taking aim at theories of the sort advanced on this blog, and later in Congressional hearings and in a Congressional Oversight Panel report, that the notes (meaning the promissory note, meaning the borrower IOU) in many cases, if not pervasively, had not been endorsed and conveyed as required by the pooling and servicing agreements, which are the contracts that govern mortgage securitizations. In other words, the industry had committed in contracts to investors to take some very particular steps to assure that the securitization complied with a host of legal requirements to assure that the investors got the benefits of the cashflows from the mortgages, and then proceeded to welsh on their deal.

Normally, this would not be such a big deal. Contracts are often breached; the usual remedy is to get a a waiver, which sometimes might involve a payment of some sort. But securitizations are particularly inflexible agreements. From the abstract of a 2010 paper by Anna Gelpern and Adam Levitin:

Modification-proof contracts boost commitment and can help overcome information problems. But when such rigid contracts are ubiquitous, they can function as social suicide pacts, compelling enforcement despite significant externalities. At the heart of the current financial crisis is a contract designed to be hyperrigid: the pooling and servicing agreement (“PSA”), which governs residential mortgage securitization. The PSA combines formal, structural, and functional barriers to its own modification with restrictions on the modification of underlying mortgage loans. Such layered rigidities fuel foreclosures, with spillover effects for homeowners, communities, financial institutions, financial markets, and the macroeconomy.

So given that the PSAs can’t be renegotiated, the securitization industry needs to find a way to argue that everything is hunky dory, despite the ever rising volume of lower court cases in which banks have had trouble foreclosing because borrower’s counsel challenges them to show that they are holders of the note (meaning not merely that they have possession, but that the securitization trust they represent is the owner). The big salvo was the ASF’s white paper, published last November, whose argument has been repeated and elaborated a tad. In effect, the white paper ignores the specific requirements of the PSA, and instead argues that “industry practices”, meaning the widespread disregard for contractual commitments, were OK. (We’ve taken apart the paper in previous posts, see here, here, and here)

As the white paper claimed:

While the real property laws of each of the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia affect the method of foreclosing on a mortgage loan in default, the legal principles and processes discussed in this White Paper result, if followed, in a valid and enforceable transfer of mortgage notes and the underlying mortgages in each of these jurisdictions. To be thorough, the White Paper undertakes a review of both common law and the Uniform Commercial Code (the “UCC”) in each of the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. One of the most critical principles is that when ownership of a mortgage note is transferred in accordance with common securitization processes, ownership of the mortgage is also automatically transferred pursuant to the common law rule that “the mortgage follows the note.”

The paper also discussed Massachusetts in particular:

Massachusetts: The transfer of a mortgage note, without the express transfer of the mortgage, vests in the note holder an equitable interest in the mortgage (an interest that can be enforced by the note holder) and the mortgage holder is deemed to hold the mortgage in constructive trust for the benefit of the note holder. See Weinberg v. Brother, 263 Mass. 61, 62 (1928); Barnes v. Boardman, 149 Mass. 106, 114 (1889); Morris v. Bacon, 123 Mass. 58, 59 (1877); First Nat’l Bank of Cape Cod v. North Adams Hoosac Savs. Bank, 7 Mass. App. Ct. 790, 796 (1979); see also In re Ivy Properties, Inc., 109 B.R. 10, 14 (Bankr. D. Mass. 1989) (“[U]nder Massachusetts common law the assignment of a debt carries with it the underlying mortgage, without necessity for the granting or recording of a separate mortgage assignment.”).

Despite the above cited authorities, the Massachusetts Land Court in a recent opinion cast doubt on the “mortgage follows the note” rule:

[E]ven a valid transfer of the note does not automatically transfer the mortgage. . . . The holder of the note may have an equitable right to obtain an assignment of the mortgage by filing an action in equity, but that is all it has. . . . The mortgage itself remains with the mortgagee (or, if properly assigned, its assignee) who is deemed to hold the legal title in trust for the purchaser of the debt until the formal assignment of the mortgage to the note holder or, absent such assignment, by order of the court in an action for conveyance of the mortgage. But . . .the right to get something and actually having it are two different things. U.S. Bank Nat’l Ass’n v. Ibanez, Nos. 08 MISC 384283 (KCL), 08 MISC 386755 (KCL), 2009 WL 3297551, at *11 (Mass. Land Ct. Oct. 14, 2009) (citations omitted).

The Ibanez case appears to stand in stark contrast to the principles embodied in the UCC. The Ibanez case is currently pending on appeal before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, that state’s highest court.

The paper, while mentioning Ibanez, nevertheless clearly viewed the lower court decision as an outlier, and asserted that the “mortgage follows the note” principle held in Massachusetts. But Massachusetts is a title theory state. As the Supreme Judicial Court said in its decision, taking the position opposite the one the ASF asserted was correct:

In a “title theory state” like Massachusetts, a mortgage is a transfer of legal title in a property to secure a debt. See Faneuil Investors Group, Ltd. Partnership v. Selectmen of Dennis, 458 Mass. 1, 6 (2010). Therefore, when a person borrows money to purchase a home and gives the lender a mortgage, the homeowner-mortgagor retains only equitable title in the home; the legal title is held by the mortgagee. See Vee Jay Realty Trust Co. v. DiCroce, 360 Mass. 751, 753 (1972), quoting Dolliver v. St. Joseph Fire & Marine Ins. Co., 128 Mass. 315, 316 (1880) (although “as to all the world except the mortgagee, a mortgagor is the owner of the mortgaged lands,” mortgagee has legal title to property); Maglione v. BancBoston Mtge. Corp., 29 Mass.App.Ct. 88, 90 (1990). Where, as here, mortgage loans are pooled together in a trust and converted into mortgage-backed securities, the underlying promissory notes serve as financial instruments generating a potential income stream for investors, but the mortgages securing these notes are still legal title to someone’s home or farm and must be treated as such.

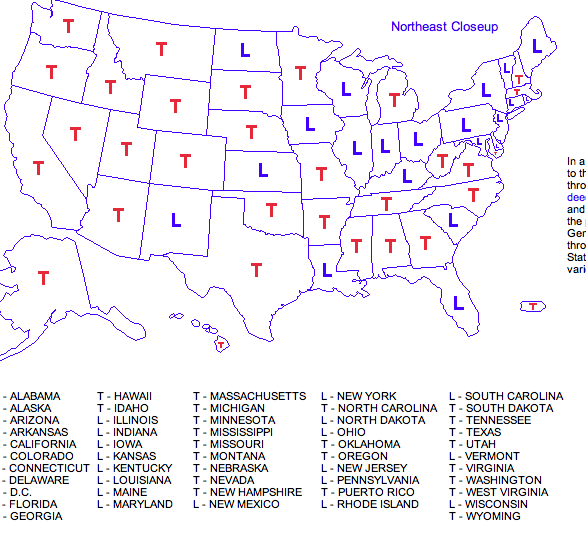

Below is a map of title theory versus lien theory states:

For the most part, title theory states are non-judicial foreclosure states.

So here the ASF managed to miss a whole raft of precedents that the Supreme Judicial Court saw as germane. And the ASF confidently asserted that the mortgage (the lien) always follows the note, when the Ibanez case suggests that other title theory states might come to a similar conclusion, that the lien also needs to be assigned. And in Massachusetts, the lien cannot be assigned in blank, because it is effectively a deed, meaning it conveys legal title to real estate. I am not certain to what degree other title theory states take that view. But even if Massachusetts in the only state to operate this way, it’s a significant enough exception to be worth taking note of in securitization procedures, yet no such effort was made.

As Tom Adams said in an e-mail:

If they were mistaken on such fundamental issues as “possession of the note trumps everything” and “the mortgage follows the note”, what else were they wrong on? How can anyone doubt, now, that the outstanding securitizations face some material risks that were not disclosed and not understood at the time the deals were made.

Even more important: how can any investor in current or future private label securitizations be comfortable that their investments are not exposed to significant material risks due to improper conveyance and why would anyone invest in such securities while these issues remain unresolved? If private label MBS have such uncertainties, how will a market for MBS outside of the guarantees of Fannie and Freddie ever really be rebuilt?

Yet as we have said before, the securitization industry seems convinced that denial is a viable business strategy.

Would it be broadly accurate to say that the reason Title theory states (where the lender remains the actual title holder, and the borrower is only nominally the “owner”) tend to be non-judicial states, while the Lien states (where the borrower receives the deed) tend to be judicial foreclosure states, is because the former represents a more centralized, authoritarian property regime, where it’s more taken for granted that the bank is always right, while the latter represents a more decentralized, “democratic” view of property, and where therefore the original laws wanted to make sure the interests of smaller parties were protected?

That was the conclusion that came to mind. If so, it’s no surprise that the Title states are mostly in the South and especially the West.

Hi,

The core reason why title states use a non-judicial process for foreclosure is because the lender does not have to sue (via the foreclosure process) to get the title to the home. The lender retained –or has held title–since the inception of the loan. They must notify the borrower when there is a default and then proceed to the advertising of the sale of the home they already hold title to.

In lien theory states the borrower actually gets the title to the house in advance, as part of the closing. In exchange they agree to allow the lender to place a lien against the house and its title as a guarantee of payment. A judicial foreclosure process is required by the lender in order to get from the borrower the title and once that part has been completed then the lender will have the right under state guidelines to advertise and sell the home which they have now acquired title to.

In both cases it is critical that the lender demonstrate not only that the borrower is in default and therefore owes SOMEBODY but that the entity claiming to have the right to foreclose does in fact have full authority (standing) to do so.

It is not nearly as complicated as the media has made it out to be. If I write on a piece of paper that I owe you $500 and you give the paper to your sister, who gives it to her mother, whose boyfriend spills beer on it and then tries to dry it our over the fireplace and accidentally drops it in the fire:

a. I still owe $500

b. I don’t don’t give a rat’s behind about your mother’s

boyfriend’s claim that he had the note so I owe him the

$500 and I had better pay up or be scared

c. Nobody can take me to small claims court (or any other

court)

d. I will pay the $500 if and when I get ready and there

is nothing anybody can do about it.

So there!.

It really is that simple. It is an unenforceable

obligation. Unsecured. Bad for somebody.

Good for anybody who has a securitized mortgage which went thru the MERS system.

I hope all struggling homeowners will really understand the implications of this ruling.

Yes, I recognize that means chaos for the financial world as well as dire implications for our economy but at some time we have to begin cleaning house and admit that we have an economy built on a house of cards, let them fall and start over.

I am almost an old lady, we need to get started soon so I can live long enough to see the recovery. I asking the Lord for another 20-25 years so we need to start soon.

Mildred

Thanks, Mildred. The part that strikes me is that even if a lender has a signed IOU for a normal loan, he still has to sue to collect from a delinquent borrower. He can’t just grab the money out of the borrower’s hand. (Not legally, that is.)

But the non-judicial states in effect do allow the foreclosing entity to do just that. So that’s why I inferred a more authoritarian attitude in the law’s inception.

WELL SAID. GO MILDRED!

Seems to be a trend these days, “Reality is what we say it is.”

I was thinking along the same lines.

A couple of other excellent examples of this come from Satyajit Das’ companion post today:

• The approach of the EU/ ECB assumed that the problem was temporary liquidity not solvency.

• The Irish economy shrank by 1.2% in the third quarter, a surprise to economic forecasters.

However, the romantics/idealists are undeterred:

Forecasts are predicated on “aspirational” growth of 2-3%.

All of which carries me back to something Hannah Arendt wrote in her chapter “Lyning in Politics”:

Under normal circumstances the liar is defeated by reality, for which there is no substitute; no matter how large the tissue of falsehood that an experienced liar has to offer, it will never be large enough, even if he enlists the help of computers, to conver the immensity of factuality.

The ASF is following the lead of our country’s politicians–if they tell a lie enough times, and can get the MSM to continuously speak of it as if it were the gospel truth, then it must be true! Only blogs like this expose the truth.

“if they tell a lie enough times, and can get the MSM to continuously speak of it as if it were the gospel truth, then it must be true! Only blogs like this expose the truth.”

I think only certain parts of the Media put a gospel truth envelope around the lies they repeat. The unfortunate part is the majority do repeat the lies without any disclaimer at all. They abdicate any responsibility to verify, question or disclaim, which gives, with enough repetitions, a de facto illusion of credibility.

Geez, everybody is happy with the ruling…

ASF is happy too…

“The ASF is pleased the Court validated the use of the conveyance language in securitization documents as being sufficient to prove transfers of mortgages under the unique aspects of Massachusetts law. Importantly, unlike the lower court, the Court also said assignments of mortgage can be executed in blank, as long as a complete chain of transfers can be shown through the applicable deal documents.”

This is a pretty bizarre reading of the ruling, since the SJC said no such thing.

Here is what it DID say:

“Where a pool of mortgages, with a schedule of the pooled mortgage loans that clearly and specifically identifies the mortgage at issue as among those assigned, may suffice to establish the trustee as the mortgage holder.”

First, note the use of the word “may”. This is hardly definitive, it can be read in isolation as the the SJC saying this was arguable (as in “may” = “does”) or that they had considered the argument but were not reaching a firm conclusion.

But you can’t even make the more aggressive reading of that sentence, since the next one states:

“However, there must be proof that the assignment was made by a party that itself held the mortgage.”

So we are back to needing to look at the chain of assignment and whether the parties that made the assignment were “holders” which generally requires both physical possession and valid ownership.

This decision in NO way supports the securitization industry argument that the PSA itself is evidence of assignment and transfer.

Where is the securitization process fraud most vulnernable to prosecution? In the execution of the PSAs? In the ratings? WHen does the PSA execution affect the ratings?

There is the shadow banking system, 5 Trillion in the US.

The stable value fund industry, 600 Billion in the US.

The securities borrowing industry, 3 Trillion in the US.

All invested by conflicted investment bankers as justified by ratings.

Excellent post, particularly given that you are under the weather! The map is particularly useful – may I ask the source?

“Comparative law” is a very dicey area in real estate, and this post points to one reason why. ASF makes a fairly glib assertion that its practices encompass all 50 states, and it is surely wrong on that. In the Ibanez case, it was pretty easy to tell that the lenders’ argument was going to fail when they claimed off-the-record assignments of security interests in their favor, and couldn’t produce one that was effective prior to the sale by advertisement, which by statute, required them to an “assignee.” This is “always” enforced* as near as I can tell. Whether the state is title theory or lien theory isn’t the issue, IMO, it’s whether the statutory scheme for foreclosing by advertisement requires an effective assignment of the security interest in the foreclosing party’s favor. This is a surprisingly lenient requirement in that the assignment does not have to be recorded in MA, but the mortgagees couldn’t meet that burden anyway. It is interesting that the Court didn’t appear to be requiring an effective real estate conveyance, just something particular enough to be able to say where the property, interests and parties are identified, there is an assignment of the property interest. While it didn’t make reference to the statute of frauds requirements for the transfer of real estate interests, it looks to me like that was the standard – the cocktail napkin standard, and that’s really low, but clear, and I suppose defensible.

Gelpern and Levitan’s chart has at least one error as well – my state is lien theory, not title theory. (I found the map shown here in another place as well, and I would not rely on it). A small error, and one that, IMO, isn’t that important, but is similar to many lender guides I have seen, which may be just as erroneous). 50 state practice is exceedingly difficult and theoretical abstractions can lead to wildly wrong conclusions about what the law is in any particular state.

The MA Supreme Court addressed the difference between title theory and lien theory in whether the note follows the mortgage in both (it “sort of” doesn’t in MA, but also “sort of does,” just as in lien-theory MN), but the mortgagees would have lost anyway, IMO, because the statute requires strict compliance on having an effective assignment or security.

Now, in my lien theory/sale by advertisement” state, the Supreme Court held essentially the same as Mass., a title theory “sale by advertisement” state, regarding the assignment of the note being also an “equitable assignment of the security interest” in Jackson v. MERS. In MA, it is described as the mortgagee of record holding the mortgage in trust for the purchaser of the note who has an equitable claim to get the assignment – but, must actually get the legal assignment before foreclosing by advertisement. The one big difference is whether recording of the assignment is required. Here it is. In MA, it isn’t.

So, both MN and MA require strict statutory compliance for foreclosure by advertisement – that all assignments of the security interest be effective, and in MN, recorded.

*”Strict compliance” is always required, except when it isn’t. For USBank and Wells, the failure to have effective assignments was pretty clearly non-compliant, and IMO, a guaranteed loss. The tougher cases are where the assignments are recorded, but defective. What level of defect rises to a non-compliant document? The MA Court, on the other hand, is saying that an assignment could be unrecordable (that is, defective), but still effective. (e.g. a bad or missing notarization?)

I can’t tell from this link whether this case is intended to be a “published” decision as case law. If not, then the key issues are not considered controversial by the Court, meaning that it wasn’t a very close call. Also, there is no dissent, and the concurrence is pretty concise on stating the requirements to foreclose by advertisement.

Finally, I think it is a mistake to characterize this as a generally pro-borrower/homeowner case. It is “pro-these borrowers” because the lenders were so sloppy. In fact, it appears that the lenders lost these cases without the borrowers doing anything – the lower court on its own voided the foreclosures. But, the Court’s holding is not obviously inconsistent (double negative intended) with holding that pre-sale MERS assignments are effective, even without s statute like we have in MN. It almost certainly means that, at least in MA, that recording fee avoidance doesn’t invalidate an assignment, because they don’t have to be recorded there, as long as they are effective.

It is published. It seems that the Mass. Supreme Court releases its published opinions by uploading to Westlaw – which is the slip printer, I believe, for the Mass. Court. PS – although hosted by Westlaw, there is not a copyright here by West. You are free to copy from the link from the court.

The heading at the top of the slip opinion page page states:

NOTICE: The slip opinions and orders posted on this Web site are subject to formal revision and are superseded by the advance sheets and bound volumes of the Official Reports. This preliminary material will be removed from the Web site once the advance sheets of the Official Reports are published. If you find a typographical error or other formal error, please notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Judicial Court, John Adams Courthouse, 1 Pemberton Square, Suite 2500, Boston, MA 02108-1750; (617) 557-1030;

Link May be found here:

http://www.massreports.com/RecentAdditions/

I agree with BS – had the PSA met the statute of frauds requirements for real estate conveyances, it would have been sufficient – if my reading is right.

I would rephrase the following:

“It is interesting that the Court didn’t appear to be requiring an effective real estate conveyance, just something particular enough to be able to say where the property, interests and parties are identified, there is an assignment of the property interest.”

The court is requiring an effective conveyance, but it is saying that the SOF is the only standard for determing that. Recordability is not required.

As a general rule, recording protects the parties against third party claims and gives notice to the world (with certain nuances). Usually, however, it is not required for making a conveyances effective.

As I said, this is a low standard, but defensible where a foreclosure statute doesn’t strictly require recording.

Thank you. And I thought I was beginning to understand. I still have questions. Yves has been beating the PSA defect drum for months. Who cares? I don’t see it likely that investors will bring down the house as long as their cash flow is maintained. And as I understand their payments are being met even in the face of record foreclosures and a flawed foreclosure process. Is it conceivable the servicers can extract enough cash from the foreclosure process to meet those needs indefinitely? Yeah, well it’s a Ponzi so maybe not indefinitely, but they’re good at Ponzi so you know what I mean.

“[H]ow can any investor in current or future private label securitizations be comfortable that their investments are not exposed to significant material risks …?” That’s a different question. How indeed? So the GSA’s compose the entire mortgage market today and will for the foreseeable future. Something tells me that isn’t an improvement.

That the registration process may not meet State laws completely blows me away. How is it possible that good attorneys can be so careful to dodge any possibility of bankruptcy clawbacks and miss something like that? How is it that it was never tested?

Investors are eating the costs of contested foreclosures. They easily run to $100,000 to $400,000. And that’s before you get to the losses when the judge dismisses the foreclosure without prejudice. In addition, some states like Alabama are very punitive re wrongful foreclosures. 3X damages to the borrowers, and the lender is also required to reimburse attorney’s fees when the action is successful. So lawyers and borrowers have every reason to go after the investors in those cases.

Investors, in other words, have plenty of incentive to go after the servicers and trustees to stop the bleeding. Deep principal mods are a much better solution than what is happening now. But they happen to be a cautious bunch, bond investors generally don’t litigate, the ASF has been making lots of noise and the issues around the PSA have gotten press only in the last couple of month.

Contested foreclosures maybe. I think I’ve see ere how few of those there are. That may be an acceptable cost. And the Servicers seem to have been designed as disposable. The Trusts maybe not so much. Anyway, I’ll take your word for it. You seem to have a handle on it. Hope you’re feeling better.

Hop

If as an investor you seek to sell your MBS but it is disclosed that even though the cash flow is good, the mortgage titles had never been assigned to the MBS, the value of this non-asset backed security will likely be in doubt. Sure you can use the revenue stream to model the value, but in the event of mortgage defaults, you are screwed. The risk goes up, the value goes down from what you payed for it. No?

The map is here.

http://title.grabois.com/

Quick comment. The court made these cited comments relative to the non-judicial power of sale. If you want to avail yourself of that remedy you need have your ducks in a row. That means proof of chain of title. The state of Massachusetts is basically letting them skip a step i.e. judicial approval to seize property. That’s why there is a requirement that the Deed of trust aka mortgage be expressly assigned in a recordable form. It doesn’t have to be recorded , it just has to be in the proper form. This is so there is no doubt about the ownership of the property. To have it otherwise, would be for one party to unilaterally determine an equitable assignment.

If the banks have the note but not the mortgage they can go to court and get their equitable assignment. The court says this.

In the lien theory states the equitable assignment is incorporated into the process as part of the judicial foreclosure.

The moral of the story is you can’t decide you own equity because of the obvious self interest. Equities have to be determined by third parties with no interest.

So not only are the MBS’ unsecured by the mortgage, the proise to re-pay is not present in the MBS. So the MBS is truly notional. It is a box full of nothing.

If the mortgage holding bank never assigns the mortgage to the trust, is the mortgage carried as an asset on the books of the mortgage holder? Greed could explain holding onto it, in additon to general ineptitude and criminality.

It strikes me that the abiding and unanswered question is: Why not do the assignments and recordings? It’s tedious, time consuming and does require the payment of fees? Is that sufficent reason to perpetrate a fraud?

Now lets suppose that in the securitizing process there are know reps and warranty frauds. Strikes me that all those RMBS tranche holders have an actionable event in that the trustee for the tranches is holding an empty bag.

How long will it be before we see some TV adverts fishing for injured tranche holders?

For a while, I have been wondering what was the basis of the oft repeated statement that the mortgage follows the note in 45 of 50 states. Which 5 state do not so hold? I have not see a cite to the source for this.

I also feel that there will be further jurisprudence in Mass as to what is sufficient to show a transfer – a back of a napkin may not work, but the signed front may.

Also, in Ibanez, one of the entities in the chain of assignments in Lehman – in Chapter 11 now. Hmm,

“How can anyone doubt, now, that the outstanding securitizations face some material risks that were not disclosed and not understood at the time the deals were made.”

The material risks were certainly not disclosed, but not understood? This is like arguing that an experienced mechanic did not understand how to perform a simple oil change on your car. Securitizers had access to, and the responsibility to use, expertise on clearly delineated law. That they did not or ignored elementary legal procedure on such massive scales can not be construed as malpractice and/or negligence but fraud.

Actually, the Levitin paper accurately recites the rule in Massachusetts. The problem was that Wells Fargo claimed that it received an assignment of the debt when it received an assignment in blank. Wells Fargo clearly received an equitable interest in the mortgage that it could have enforced by suing Option One (if only they still existed) to deliver the mortgage it still held in constructive trust.

The mortgage follows the note in Massachusetts when there’s a proper assignment and not an endorsement of the note in blank by the previous holder. But again, the SJC expressly stated that an imperfect assignment caused by an endorsement in blank isn’t an incurable condition.

Hilarity ensued here when the Land Court judge asked Wells Fargo for … documentation and stuff.

Another significant facet of the Ibanez ruling is the holding that an “assignment in blank” of a mortgage is *void*, at least in Massachusetts. When a promissory note is indorsed in blank under the UCC it becomes “bearer paper” –whoever holds it is entitled to payment in accord with its terms. (“Money doesn’t care who it belongs to.”) But as for the interest in real estate that *secures* a note, the Ibanez court agreed with a key point that counsel for the borrower made in briefing the case: “no matter how viewed, title to real estate is not, and should not be treated as, bearer paper.” (brief, p. 31 n.25)

As for the notion that “the mortgage follows the note”, the Court recognized that this does not make the note and the mortgage into Siamese twins — the mortgage may lag some distance behind the note, in other hands, and the creditor must see to it that they are properly re-united before the security interest can be enforced.

Keep up the good work!

‘Gwailo, Esq.