Paul Krugman correctly anticipated that I would be unable to resist taking issue with him again regarding his view that the recent increase in commodities prices are warranted by the fundamentals.

Note that I am not saying in this post that “commodities prices have increased as a result of speculation.” That takes more granular analysis of conditions in various markets; we’ll be looking at some that look suspect in the coming days and weeks.

I intend to accomplish something much simpler in this post: to dispute the logic of Krugman’s overarching argument. He professes to be empirical, but as we will show, he is looking at dangerously incomplete data, so his conclusions rest on what comes close to a garbage in, garbage out analysis. And that’s been a source of frustration given his considerable reputation and reach.

Here is the guts of Krugman’s reasoning, from a recent post, “Signatures of Speculation“:

OK, how can speculation affect this picture? The answer is, it has to work through accumulation of inventories — physical inventories. If high futures prices induce increased storage, this reduces the quantity available to consumers, and it can raise the price. And you can, in fact, argue that something like this has been happening for cotton and copper, where there are apparently large and growing inventories.

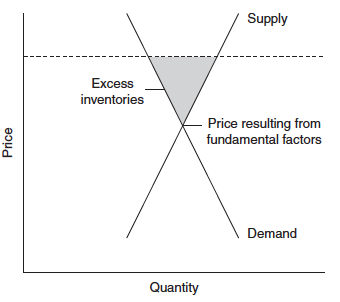

I’m taking the liberty of putting in my redraw of an older version of his cartoon; I think it makes the point more clearly:

This is another statement of his argument in a 2008 post:

My problem with the speculative stories is that they all depend on something that holds production — or at least potential production — off the market. The key point is that the spot price equalizes the demand and supply of a commodity; speculation can drive up the futures price, but the spot price will only follow if the higher futures prices somehow reduces the quantity available for final consumers. The usual channel for this is an increase in inventories, as investors hoard the stuff in expectation of a higher price down the road. If this doesn’t happen — if the spot price doesn’t follow the futures price — then futures will presumably come down, as it turns out that buying futures produces losses.

So Krugman’s point is that if the price is higher than the level determined by supply and demand (the dashed line), you’ll see inventories, or more accurately, an increase over “normal” inventories, since the real world is not frictionless and there are various buffer stocks in the production system. And note he is NOT making a strong form claim that the speculators are the ones doing the hoarding (“usual channel” falls short of that); it’s merely that if the price is too high (say as a result of people in the cash markets somehow getting bad signals from all those evil speculators in the futures markets), the result will be opportunistic stockpiling.

That is not where our bone of contention with Krugman over oil in 2008 or our reservations now lie. It’s over statements like this:

But for food, it’s just not happening: stocks are low and falling.

This is simply not knowable, or at least not to the degree of confidence that Krugman has.

One thing I do on a regular basis is analyze information about market size and activity, and over time, it’s taken place in a very wide range of industries (yours truly specializes in oddball deals). Unless you are dealing with markets in which the government demands extensive reporting (like Japan, the data you can get in Japanese is just fantastic) or ones where you have a system of centralized reporting or other tight controls (like pharmaceuticals), it is very difficult even to get decent estimates of market size. So a basic issue is: understand the integrity of data.

Now consider commodities. Inventories can be held LOTS of places: storage facilities by private owners (major refiners such as flour mills), finished product, private speculators (there have been reports for years of base metal stockpiling in China), even the consumer level (during the oil crisis, people kept their auto gas tanks fuller due to the even-odd license plate gas station system). Consider what a monstrous supervisory apparatus around the world would be required to track all or even a substantial portion of where inventories in various commodities could be held.

The logical fallacy for Krugman is the official inventories he is looking at are only a subset of the places where inventory can be accumulated, and in many if not most cases a small enough subset that he cannot reach conclusions of the absence of inventory accumulation. For instance, in our long running discussion about oil prices in 2008, Krugman focused on official inventories. We pointed out that that storage was limited and actually surprisingly impractical. Those figures did not include the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (which was increasing its holdings during the 2008 price rise) nor did it consider that oil can simply be stored in the ground, via reducing well output. Our resident petroleum engineer Glenn Stehle explains:

Glenn Stehle on Reducing Oil Well Production

Now let’s look at one of Krugman’s current concerns, which is food price increases. The blog Clouded Outlook (hat tip Ed Harrison) tells us how the food “inventory” data that Krugman is relying upon is woefully incomplete:

Since Krugman lives in New York, it is perhaps understandable that his knowledge of farming is a little limited. There is no such thing as data on inventory. The USDA produces a time series called grain stocks. This number is not the same as inventory. This stocks number has very limited coverage, focusing mainly on government holdings of grain. The USDA produces these estimates largely by looking at grain reserves in the US and reading reports produced by other governments.

Most countries run strategic grain reserves, and there is some limited data for what governments are holding. However, these reserves are disbursed across many sites across the world. Often there is wastage, theft, and miss-reporting. To put the issue in perspective; does anyone really think that the grain supply numbers coming out of say, Chad are accurate? Undoubtedly, the Chadian authorities are doing their best, but gathering comprehensive data on grain storage is not as easy as New York journalists might think.

In some parts of the world, grain markets are subject to government intervention, and price controls. This increases the incentives for corruption and misreporting. In more than one country, grain reserves have mysteriously disappeared, especially when food prices have suddenly accelerated. We should never forget there are some very powerful incentives at work here.

To make the point more forcefully, does anyone really think they know how much grain the private sector are holding? If private wholesalers are hoarding grain, I doubt very much that are reporting their stocks accurately to government officials. If prices are going through the roof, the incentives to hide grain are very potent.

Just to be clear, I am not saying we know nothing about grain stocks. I am sure the numbers coming out of the US, the EU and Canada are reliable. But strategic grain stock numbers from Russia, Kazakhstan and Ukraine? There I pause for a moment and wonder. Maybe, these numbers might be in the ballpark of the truth, but I would treat them with caution. As for private sector holdings of grain, only the Almighty knows that number.

There are estimates of production, which are partly taken from satellite imaging, and assumptions about yield per hectare. There is an obvious relationship between amounts produced last year and likely stocks this year. It is helpful, but I would feel uncomfortable about relying on those numbers.

Furthermore, when I hear that USDA estimates project a 5 percent decline in production, I am inclined to believe it. Nevertheless, reported harvests have been very good over the last few years. Even a five percent decline still puts the projected 2011 harvest up there in the top five years over the last two decades or so.

Nevertheless, these qualifications shouldn’t detract from the point that we shouldn’t take too seriously any argument suggesting that speculation in food markets is implausible, simply because there is a lack of inventory build-up. It is the sort of argument that city folk make. Country people know better.

The Australian blog MacroBusiness, in a recent post “Paul Krugman is Wrong,” reads the UN Food and Agriculture Office reports differently than Krugman does:

So, what about food prices. According to Krugman:

Not much evidence of hoarding, as far as I can tell. So this is straightforward supply and demand. Demand may be up to some extent because of that emerging-market boom. But if you look at the FAO reports it becomes clear that the key thing for cereals prices is that production is down in advanced countries, largely owing to terrible weather. And yes, it’s likely that climate change has played a role.

Well, this blogger read the FAO reports. And yes, one does show a small drop in wheat production. However, another also says the following (h/t threedogsandakid):

In its 2009 Trade and Development Report, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) contends that the massive inflow of fund money has caused commodity futures markets to fail the “efficient market” hypothesis, as the purchase and sale of commodity futures by swap dealers and index funds is entirely unrelated to market supply and demand fundamentals, but depends rather on the funds’ ability to attract subscribers….

The Groups recognize that unexpected price hikes and volatility are amongst major threats to food security and that their root causes need to be addressed, in particular:

a) The lack of reliable and up-to-date information on crop supply and demand and export availability;

b) Insufficient market transparency at all levels including in relation to futures markets;

c) Growing linkage with outside markets, in particular the impact of “financialization” on futures markets;

d) Unexpected changes triggered by national food security situations;

e) Panic buying and hoarding.

Now while there are markets where the inventory data may be more comprehensive (for instance, where the good are perishable, so the requirement for refrigeration and cold storage limit both distribution and inventory options), this pattern strongly suggests that at a minimum, relying primarily on inventory data is risky.

It therefore behooves analysts and commentators to look at market mechanisms and price movements relative to underlying changes in supply and demand before concluding that speculation isn’t playing a role in commodity price increases. Many of the people making these claims are not newbies; in fact, some are professionals with decades of experience, and most have nothing to gain by using the “s” word; in fact, they would damage their reputations if they cried wolf. That does not mean their opinions should be taken as a matter of faith, but it at least suggests that their arguments deserve a serious hearing.

Is speculation a euphamism for inflation?

Speculation is more the cause and inflation the effect (if the assumption is true that rising food/commodity prices are due to speculation).

Well he has a point: the excess liquidity in the markets due to inflationary policies in the past decades lead to speculation at some point in inelastic demand markets (oil, food, etc.). Off course if there is a recession all that liquidity will withdraw to other markets (like logn term bonds) again, hence price volatility in different assets is due to inflationary policies in the past, and not the contrary.

Take in mind I’m not saying that (contrary to ‘austrians’ and their rabling about QE) current liquidity measures are causing this, but this is a byproduct of the past.

This does not make any less inmoral or whatever, but that’s not what we are talking about here.

—

excess liquidity in the markets due to inflationary policies in the past decades lead to speculation at some point in inelastic demand markets

—

For the sake of argument, let’s assume Krugman’s supply constraint assumption is correct; does anyone think that speculators could resist participating in that event?

The drug hasn’t been invented that could keep speculators from betting on a supply constrained market.

On one side we have the hottest climate year

on record, with the first ever 100F temperature

reading in Moscow, devastating wildfires and

drastically reduced grain production in key

production areas.

On the other hand we have the hypothesis that

somehow, somewhere, the Fed has caused speculators

to hoard physical supplies of food, which is

rotting somewhere, somehow. Nobody has reported

on those secret stockpiles of speculator food,

people are actually out in the streets rioting

due to lack of or too expensive food.

The same people are also making the argument

that human-caused global warming is not happening

and that the Fed is the root of all evil.

Which explanation is the more likely one to you, that

it’s a well documented, extreme heat events caused

restriction of supply pushing up prices by 40%,

or that there’s some evil speculator hoarding

massive stockpiles of rotting food somewhere,

pushing up prices by 40%?

Yves, I agree and wrote pretty much the same thing in my blog a week ago. I don’t dispute Krugman’s Argument that bad harvest decreased supply. But we have certainly also an increased demand on the cash market due to hoarding by private persons. They fill their food inventory to hedge against future price spikes. Note that this is a very rational behaviour as due to the inelastic supply curve the risk of very steep price increases is particularly large, much larger than the prices will drop if the supply is back to normal. Given the current drought in China, that risk might even become real.

So do you think speculators, instead of

speculating in currencies, now command

tens of millions of tons of slowly rotting

food? Food which no-one has reported on

yet, which no-one has seen, which no

numbers suggest exist? And this invisible,

huge stockpile of food hoarded by someone

and rotting somewhere unnoticed is supposed

to have increased global food prices by 40%?

And this argument is supposed to discredit

the rather simple factual observation that

last year’s record hot weather has hurt

the harvest and has put a squeeze on

world food supplies, combined with a

stronger than expected uptick in demand?

Occam’s razor anyone?

He professes to be empirical, but as we will show, he is looking at dangerously incomplete data, so his conclusions rest on what comes close to a garbage in, garbage out analysis. And that’s been a source of frustration given his considerable reputation and reach.

The fact that he has such a fraudulent reputation should be a source of frustration as well. The scam he’s running here is typical of him.

Like most economists, he starts out with a fundamental lie, that supply is at some natural limit, and another, that the price is at some equilibrium naturally arising from a confluence of supply and demand. The truth is that under capitalism, and especially globalization, supply and price under severe artificial, political scarcity constraints. In the case of food, these include subsidized commodity monoculture, globalization treaties which force dumping of these commodities upon national markets, biofuel mandates, neo-colonial land grabs, IP regimes, and the IMF-driven gutting of public agricultural investment in much of the global South.

Put it all together, and the price of food is already teetering on the verge of absolute disaster even under the best, most stable circumstances. So how much speculator involvement could be needed to cause a non-linear spike?

The global food market is naturally based overwhelmingly on subsistence farming and growing for local and regional markets. Globalization violently forced the whole thing into the commodification strait jacket, the most extreme example of the tail wagging the elephant the real economy has ever seen.

But Krugman, having safely hidden away this whole neoliberal overheating of this most critical of markets, literally life and death for billions, can then try to dispose of the the effect by attributing it to a failed harvest. But even that doesn’t make any sense, since it’s still the artificial destabilization of the world’s food markets which makes it possible for any failed harvest anywhere to have such an effect.

It’s globalizers like Krugman who have radically destabilized the literal physical sustenance of our lives, such that any slight increment, speculatory and/or bad harvest, can plunge billions into starvation.

And why does he argue this today? Is he still pushing his malign agenda, or is he merely trying to cover up for his past crimes? Either way, by extenuating these crimes against humanity, he continues to commit the same crimes.

I certainly miss something here, but I don’t see speculation has to be tied to rising inventories. Futures contracts don’t require the seller to have the item he wants to sell in stock, he may even chose to settle in cash instead of physically delivery. Plus either side can sell its end of the contract at any time on the exchange.

Futures contracts are the ideal tool for speculation, especially if big money comes in that has no actual interest in the underlying commodity, i.e. doesn’t need it for their business.

Krugman’s argument is that futures are completely irrelevant since they have to converge to the cash market at contract maturity. Thus per him all that counts is the physical market.

That just means you close your contracts well before maturity.

If his theory is true, the contracts would at any time have to trade at pretty close to fair price (=spot + costs of holding), after all, if we’re on the theory plane, you can take the view by buying spot and holding as well as buying a future.

A simple empirical test would be to check how much off the fair price futures trade now and compare it to the situation say 5-7-10 years ago. You could then measure the degree of “speculation” by comparing the long-term averages of the value.

Moreover, if there’s a lot of speculation in the market, one would expect a steeper convergence to spot as the contracts gets coser to expir than if the difference is just holding costs + some small noise.

I’m still confused as why anyone would ever believe Krugman is an economist?

Or Mark Zandi, for that matter?

Humm, a Nobel and John Bates Clark prize winner is not an economist? Just who would you include in the profession? Glenn Beck?

Your comment syas volumes about you, and very little about Krugman, or Zandi for that matter.

He may have been an economist in the past, but he’s long stopped doing any serious economics work or basing his writings on sound economic data or principles. What he is is a very well-paid propagandist for right-wing, liberal, corporate interests. His goal is to preserve Corporate America, the dominance and profits of the Democrats, and, above all, to protect the dollar. He’ll say anything to accomplish these goals.

Consider his bizarre and inaccurate comments on the Euro. Does he really believe that a fiat currency backed by only a single country could possibly compete against a multi-lateral currency backed by many countries? Hard to believe. Or his farcical claim that China is manipulating the currency, based in part on his obsolete belief that changing the currency has a significant effect on exports. Or his support of debt and deficit financing, which is just beyond absurd at this point given the indisputable evidence that it’s the countries which manage their budgets (like China and Germany) that are doing well, while virtually all of those running deficits are doing badly. I used to have a great deal of respect for him, but no longer. He’s obviously sold out, big-time. I think he’s the most dishonest economist around now. Kind of sad really, since he was good once.

Nobel and John Bates Clark prize winner is not an economist?

Well la de da!

I think you’ll find most people around here aren’t impressed by bogus credentials, or by those who are still foolish or pernicious enough to respect such empty, worthless nonsense.

We care about one’s actions.

This is nonsense. Just because the futures and spot converge doesn’t mean speculation via derivatives has no effect on the underlying over time. The e-mini S&P futures do $100+ billion in notional a day; whether specs are net long or short has no effect on the stock market? News to me.

Next month that contract is going to expire so what in the world will I do? I’ll roll my position. If I’m long I sell the front and buy the June. At the end of the day I’m still long, no different than if I bought and held the equivalent basket of stocks.

We’re not talking about a corner here where you would need to go into the spot market/take delivery to take physical suppy off the market. People are simply betting ag prices will go higher (for any number of reasons) so they buy futures, options, etfs etc. and roll them (or the etf does) until the time they don’t want to be long.

Actually Jon, Krugman is wrong that future and spot converge. That is actually why he is wrong. If they did converge, meaning IF spot and future was determined differently then the implications would be huge: krugman would be right.

Sigh, I /facepalm reading this comment of mine. I wish I could say I was drunk or high.

>nor did it consider that oil can simply be stored in the >ground, via reducing well output.

But that would show up as a fall in SUPPLY! Oh well…Krugman does not understand how the real world works…NOT

I think the point was that this would be considered ‘hoarding’ in some sense. Similar to the market interference that occurred in the Arab states during the oil shocks.

Wood – trees… please distinguish…

Actually, I should be more specific. If the oil were ‘turned off’ at the tap, it would show up as a fall in the supply curve – not an increase in inventories. Thus, it would be a ‘tampering’ with the price that would NOT show up as excessive inventory. Thus, it would not show up in Krugman’s analysis – which assumes markets to allocate prices perfectly without any possible ‘interference’ by people who ‘hoard’, without this ‘hoarding’ showing up as an increase in inventories.

In a sense these ‘hoarders’ are speculating. As they are withholding goods from the market in the hope that prices will rise. At the same time they are helping to facilitate these price rises by holding down demand. Krugman’s argument cannot deal with this variable because he assumes that speculation will always result in the build-up of inventories – but, in the real world, it can actually occur at the source and affect supply prior to any market purchase.

All this was noted long ago when economists attempted to deal with issues of monopoly pricing (Kalecki is a good example). Personally, I’m surprised that Krugman adheres to the arguments he adheres to – but then, Krugman often surprises me… he often seems to be agreeing with the conventional view simply for the sake of agreeing…

What about mid-level speculators? Inventory sitting in the pipeline?

I go to the supermarket in the US often. Over the past year I have seen more and more large bags of rice (20-40 lbs) being displayed in very high value locations within the store. They don’t move quickly, but do move eventually. Not the usual turnover that would be expected at that retail location in the store.

Did Someone within the supply chain buy too much? When?

So what if the reports of stockpiles are too high?

While I agree that while “the Chadian authorities are doing their best, but gathering comprehensive data on grain storage is not as easy as New York journalists might think”, there is an equal chance that they are wrong on the low side as on the high side.

Do not see how you can criticize anyone working with the data available. Just because there are “lots of places” where grain, or oil, can be stored, does not mean that the data is necessarily low.

That’s true to the extend that “price” means “spot price”.

Ai, wrong reply button…

Yves – curious to know what is your view on his statement:

“..But food is a physical commodity, and plays in the financial markets can only move the price to the extent that they affect physical flows and stocks.”

That’s true to the extend that “price” means “spot price”.

Someone needs to find the mechanism whereby a lot of these commodities are priced on the spot market…this is how you can judge whether Krugman is right in his hypothesis with regards to agricultural commodities.

The problem with doing this is that even if you were to find a mechanism whereby you understood how the futures price affected the spot price(if it all) its completely unknowable what came first: the chicken or the egg. This is because food can be so easily stored and hoarded by anyone in the market. So lets say for example the price of wheat jumped from $5 to $7 in the futures market due to a small supply shock. What happens? Fear of the price going higher causes hoarding by some consumers and some producers. Or…did the supply shock cause the hoarding? Or…is demand for food(ie consumption) just going up like the futures market is predicting? Or…(insert other argument here). What Yves is arguing is that nobody ever really knows what the total stock of a particular food commodity is at any given time.

The unfortunate thing about food is that it is a commodity that to some extent is more price inelastic than other goods, so everyone knows that it will always be demanded to some extent at any price…because the alternative is death.

The problem is that, yes, there is no doubt speculation is playing a role in the price of commodities(all commodities) skyrocketing. How much of a role is hard to know, and it’s dangerous to assume that it’s even mostly speculation(with regards to food) because if you try to counteract it with policies to prevent it you might be doing more harm in the long run. It’s really a scary thing to tinker with. That’s the point of the futures market, to make that determination in the form of price.

I can foresee an alternative, but it would have to take an engaged, active government and business(in all countries) so that these goods can be priced more fairly for people around the globe. The way this can be done is through better data analysis(that you can actually use to tinker with price, either through government fiat or for better information that the futures market can use). Some, maybe even Yves, may balk at that suggestion, but you mustn’t forget about the most important thing: the 29th and 30th day in the pond with lilypads in it. The argument is that on the 29th day the pond is half full of lilypads, and on the 30th day they double in size again and take up the hole pond(basically an argument of what can happen with human beings, growing tooo fast and won’t be able to keep up with it when 30th day arrives). It’s a Malthusian argument but it’s something very, VERY important that governments acted on in the 70s. In particular you must remember the Club of Rome. Think of Planned Parenthood. Again, this has huge implications, and why it’s something I personally don’t want to touch until I see something to change my mind…and this is coming from someone vehemently against oil speculation and who has an article that will be posted here this weekend.

Gack. I hate it when you and Krugman disagree. I trust you both.

Your mistake is trusting Krugman. Personally, I find the man affable and earnest, and si I like the persona that comes across in his writing and personal appearances. I don’t trust him, though. His continued success rests on pushing a failed ideology (economics generally; I’m not singling out his version of it).

Interesting…US wants to expand SPR again, to one billion barrels.

http://blog.gasbuddy.com/posts/Storing-one-billion-barrels-of-oil-expanding-U-S-reserves/1715-434728-495.aspx

So, we’d be sitting on 100 billion of US owned fuel…..

“In some parts of the world, grain markets are subject to government intervention, and price controls. This increases the incentives for corruption and misreporting. In more than one country, grain reserves have mysteriously disappeared, especially when food prices have suddenly accelerated. We should never forget there are some very powerful incentives at work here.

To make the point more forcefully, does anyone really think they know how much grain the private sector are holding? If private wholesalers are hoarding grain, I doubt very much that are reporting their stocks accurately to government officials. If prices are going through the roof, the incentives to hide grain are very potent.”

I like the ‘conventional wisdomness’ of this post. First the author says that price controls increase the likelihood of corruption – presumably assuming that the absence of market mechanisms leads to corruption. Then, in the next paragraph the author concedes that private wholesalers might indeed be hoarding for precisely the same reasons – which, essentially, corrupts the market mechanism.

Same effect – just that different people profit. I think its time to learn a key lesson. Corruption isn’t ’caused’ by public sector interventions any more than it is ’caused’ by private sector greed… its ’caused’ by a rotten infrastructure that allows actors to engage in shady activity without being subject to punishment!

The price for grains is not a market price alone … You must also include the perceived social costs for governments that run short of foodstuffs causing hyper food inflation and severe social unrest … From Ellen Brown’s

“THE EGYPTIAN TINDERBOX: HOW BANKS AND INVESTORS ARE STARVING THE THIRD WORLD”

“In a July 2010 article called “How Goldman Sachs Gambled on Starving the World’s Poor – And Won,” journalist Johann Hari observed:

Beginning in late 2006, world food prices began rising. A year later, wheat price had gone up 80 percent, maize by 90 percent and rice by 320 percent. Food riots broke out in more than 30 countries, and 200 million people faced malnutrition and starvation. Suddenly, in the spring of 2008, food prices fell to previous levels, as if by magic. Jean Ziegler, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, has called this “a silent mass murder”, entirely due to “man-made actions.”

Some economists said the hikes were caused by increased demand by Chinese and Indian middle class population booms and the growing use of corn for ethanol. But according to Professor Jayati Ghosh of the Centre for Economic Studies in New Delhi, demand from those countries actually fell by 3 percent over the period; and the International Grain Council stated that global production of wheat had increased during the price spike.”

So, by juicing the spot market through a minimum of storage the panic buying begins … not from brokers who can’t sell it at a higher price but by governments that can’t afford not to have it for fear of larger social costs …

And just for the record …

Kissinger: “Control oil and you control nations; control food and you control the people.”

“When everyone is oout to get you, paranoia is just being careful.”

Woody Allen

If you own something and you think it will be worth more in a week, will you sell it tomorrow? Would you buy more and keep it until next week? That’s the “s” word…

Hi Yves,

I appreciate when you engage Krugman re: your disagreements — I find the exchanges quite enlightening. Along these lines, I was wondering whether you might be able to address the arguments Krugman makes in another recent post (full blog post would be great, though I’ll take what I can get). It’s a topic I (and perhaps many of your readers) find to be even more pressing than commodities speculation:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/01/25/are-low-rates-a-subsidy-to-banks/

Thanks!

In real estate market, there certainly was speculation, and it certainly manifested itself in physical inventories, i.e. unoccupied housing bought for resale rather than use. Just look at Florida or Nevada.

As for sub-prime, it’s quite an interesting question. The number of sub-prime housing bought as non-primary residences was probably insignificant. So was there hoarding, and what form did it take? – I’m not sure.

wrong place, meant to reply to anon

Absolutely incorrect if you include Alt A loans. In AZ and Nevada, second and investment properties were half of the houses sold during the boom.

This to me ignores the correlation/causation argument. The question is, when would the Fed consider jacking up rates? Certainly not with low unemployment…certainly not with low inflation…yet they would consider this when banks actually start making a good amount of loans again. The only way banks could do this is if they sold off any excess treasuries. So in fact those treasuries would no longer be on the books once rates start going up.

So in other words, low rates ARE subsidies to banks.

Banks don’t need any money to make loans, they invent credit. They need a supply of funds to cover what they might owe other bankers is all. Bennie has given them enough to write $1 trillion in hot checks and destroy the interbank lending market.

…within limits. The required reserve ratio limits them somewhat.

So the prices of housing property prior to sub prime crisis were due to maeket supply and demand and not speculation at all?

Yves,

There is still no answer to the question: “Is speculation possible without hoarding?”

So it is difficult or impossible to accurately estimate physical inventories. If I get it right, that means you argue that Krugman’s model is correct, but cannot be used due to lack of reliable inputs (which you also mention in eConned). But is there no interplay at all between futures price and spot price?

I find it quite frustrating that there is no clear answer to even such a simple question as above, with hundreds if not thousands years of historical data behind.

Abe,

Stay calm my friend, an answer to your question will be available on this blog this weekend.

Um, the point of the post is getting “reliable data” on what is happening in the PHYSICAL market for commodities is difficult to impossible. Ergo, your assumption that there is “thousands of years of data” is incorrect.

I even have a brief discussion in ECONNED as to how the most basic relationship in economics, the little supply-demand lines intersecting (as in the chart in the post) is not proven.

Milton Friedman said it best: “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”.

And Rogers was able to cash in on agricultural inflation by predicting it. The argument seems to depend on how you define monetary inflation

There is speculations because there are no shortages of the commodities in question. Simple as that.

Yves, I believe that the argument you are having with Dr. Krugman is not merely whether fundamentals (I understand that both Russia and China are suffering crop failures and low yields due to drought) or speculation are fueling the startling runup in commodity futures, I believe that just behind this argument is the granddaddy argument – Is the rapid monetary expansion being produced by the Fed causing rampant speculation as the future value of bucky is being undermined. As Bernanke hired Krugman at Princeton, and because he is a devout Keynesian, I suspect that Dr. Krugman is not seeking “understanding” as much as he is trying to find support for his “book.” That is, the argument is unwinable as his mind is made up. Thanks for trying though.

Next assignment, you might calculate the loss in discretionary purchasing power to the average American caused by this speculation/Fed policy as that number would directly impact employment. Is it rational to say that Bernanke is rescuing the banks on the backs of workers?

This kind of argument is generally correct(that investors, in a low interest environment, are going to other places to seek yield) but totally misguided.

Rather than asking what can be done to limit commodity speculation on the futures market(and just an FYI for those who think they know the difference: the futures market on ICE actually controls the market on NYMEX to some degree now) you instead blame the environment. Direct your energies on seeking an effective speculation limit or other proposal so this stops. Given, however, that you understand little about the economy and the necessity of ZIRP, and probably just want to bash the FED because it’s a favorable habit of yours…that probably wouldn’t happen.

Huh? Look, ZIRP may have made sense in Sept 08 through Mar 09 to stop the freefall. Since that time, ZIRP and QE have caused speculation and price bubbles. So, your assumption that I love to bash the Fed is correct inasmuch as I believe MMT/Keynesianism policies in the globe’s largest economy has global implications, including hunger and civil unrest in the ME and commodity inflation here. Yes, I know that undoing these policies would hammer the U.S. economy for a time, however, current policy is unsustainable in any event and the question is – would you prefer to see a painful withdrawal or a rapid loss of control? BTW – what the hell is a “speculation limit?”

Position Limits.

Was the above discussion (all the way from Krugman, Yves, and through all previous comments) unsettling to you? It was to me. But this should not be surprising since economics in both theory and practice (application to a real world question like food prices) is incoherent. It consists of bits and pieces of historical and contemporary theories based on incorrect assumptions and seriously flawed reasoning. There are so many different economic theories, with bits and pieces accepted as truth by some people but rejected as false by others that none of us, not Krugman, Yves Smith, or any of the commenters, including me, can have any confidence in so called economic reasoning. All the above proves this. And the biggest example of incoherence and contradiction built into economics is the hoary supply-demand cartoon (And what a good word for it). Supply and demand curves are not straight lines. They are not nicely curved lines. They could be anything. So nothing can be deduced from them. You can’t reason from these silly cartoons. Economics is not a science. It’s a Tower of Babel.

Yves, I think that when many people hear that commodity prices are rising due to speculation, they think that this is the speculators driving up prices of contracts. However, PK holds that financial assets are not real assets and there has to be some transmission to real supply and demand going on for prices of real resources to rise and get translated into final goods prices. That is to say, there has to be either a real shortage or a shortage resulting from leakage, e.g., rising inventories.

If this is not the case, can you explain in briefly in a why that ordinary people can understand, what is happening?

For example, a lot of people are reading complaints from emerging countries that QE and low rates are causing the rise in commodity prices because it is fueling speculation. But it is not explained how this is happening. There are also a lot people that think that QE or low rates is causing commodity speculation that leads to food and gas price increases in the US, even though the trend of core inflation is downward sloping.

”

complaints from emerging countries that QE and low rates are causing the rise in commodity prices because it is fueling speculation. But it is not explained how this is happening.

”

Au contraire

Without QE1,2,3,4….. deflation threat would then require tax reduction for lower caste which would in turn raise demand for food and food precursor of energy. i. e. commodities. QE prevents flat-tax-cut of higher personal exemption for everyone the same. QE thus prevents inflation of survival items, food etc.

It is possible, however, that the perception of QE staving off flat-tax-cut will be merely temporary thus QE becomes merely news of news to come, news of upcoming tax cut thus food inflation.

qu’est ce vous pensez

?

It is simple. There are short and long commercials. The long commercials are being drowned out by the speculators. Not to mention some of these speculators have the capacity to run corners as a group. Yves mentioned cotton. Much of the cotton in storage has been there for decades. I have sensed that so much cotton, coffee and cocoa was stored in Indonesia in the late 1990’s that the bankruptcy there put the product on the world market and collapsed the prices. We had droughts in the Texas Panhandle and in other cotton producing regions for several years back then, yet the price of cotton collapsed from around 80 cents to 29 cents between 98 and 02. This is totally contrary to the customary supply and demand nonsense. About 02, the trend of liquidation reversed and we have had this commodity bull market going on. There are a lot of positions spoken for, whether delivery takes place or not. The buyers have to pay the price regardless. The farmer will sell on the exchange for the right price and if it fall, he will take his gain and keep his grain.

“Not to mention some of these speculators have the capacity to run corners as a group” Bingo, and nice to hear it said by someone who actually works commodities. Krugman just won’t turn this particular rock over and look at the squirmy things beneath it. His intellect shrinks from that.

Simple fact:

Farmers that can, often store their product.

They do this because the prices vary substantially during the year, and selling for a good price is obviously beneficial to them. So if they think the price of their product will be going up, can and do store as much as they can and hold it until they see what they think is the best price.

To my knowledge, there’s no official reporting of this. (I wouldn’t expect farmers to report it honestly if asked: this is important competitive information for them.) I’ve seen this done with corn and (soy) beans for a whole season when prices were poor, and have no doubt it takes place for wheat as well.

Granted the “official” inventories are a small subset of the total inventories, which would include the pantries of every kitchen in the world. However, one would expect that if there were a big increase in total inventories, at least some of it would show up in the most visable areas.

My take is that there is an underlying fundimental cuase (poor harvests, higher demand for meat rather than just straight grain based diets) that speculators have grasped an thus exacerbated the move. In the absence of the futures markets, prices would still be moving upwards, but probably at a slower rate (but would eventually get there).

That, and money looking for a place to park itself, is essentially it.

Try here from krugman:

http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/opec.html

“So there is a definite possibility that over some range higher oil prices will lead to lower output. And given highly inelastic demand, as Cremer et al showed, that means that you can have multiple equilibria. Figure 1 illustrates the point: given the backward-bending supply curve and a steep demand curve, there are stable equilibria at both the low price PL and the high price PH.”

See figure 1. Or, better yet, draw a Y. Now draw an upside-down Y attached to the first Y at the bottom of the first Y.

Can there be a “line” between Plow and Phigh where the supply and demand curves are vertical or are almost vertical allowing speculators the ability to price manipulate?

What about subsidies in countries when prices spike in oil and/or food?

There is one thing that drives oil supply, the need for cash flow. Most of these producing countries are far from rich, contrary to popular belief. There is also debt involved. Saudi made the mistake of thinking they could be the swing producer in the 1980’s and lost their market share. They had to make it a game of Russian roulette to put discipline back in the markets. Had Saudi not done so, they would have been put out of the market entirely. I think history has shown these guys they need to sell as much oil as they can in a good market. There was more oil in the world than could be used for a good part of the 20th century and supply was restricted. Maintained price will produce a new supply, count on it.

There are two key points: commoditization and financialization. Commoditization pools access to a good, eliminating most of the small local markets in favor of national, then international ones. This is supposed to smooth market prices but at the loss of individual control at both the buy and sell ends. Ideally speculation is used for price discovery. It represents the best guess of traders on price given their guesses on supply, demand, and market dynamics, that is fundamental and technical considerations. They can do this not only for current but future pricing.

Enter financialization or the technical side gone wild. Just as commoditization eliminates the vagaries of local markets, financialization eliminates most of the differences between commodities. They are treated not as physical quantities but, via futures contracts, financial instruments. Spot prices become unimportant. The action and the money is on the futures side. Krugman is completely wrong that futures prices converge to the spot price. It’s the other way around. The spot price follows the futures price. The futures price is “discovered” by the dynamics of the futures market itself. This represents a very different kind of speculation because it is only tangentially related to traditional market fundamentals, i.e. supply and demand for the physical commodity. Rather it is determined by the supply and demand of the financial instrument. There is no one to one correspondence between the physical commodity and the futures contract for it. The futures market is far larger and unsurprisingly, dominates pricing.

I would also point out that today’s Krugman graph has the same problem as the one used in his post yesterday. Classically, for a given supply, the demand line should look like the one he used. High demand, high price, and low demand, low price. But if you vary supply as well, then it is the difference of these two that determines price. Excess supply, low price. Excess demand, high price. The supply line is screwy because it indicates that as supply increases, price increases. This would be a great incentive for widget makers everywhere to ramp up production, if only it were true, but it isn’t.

To recap, in financialized commodities markets, the real supply-demand dynamic is for the financial instrument, not the physical commodity. The physical commodity plays only a limited role in the market.

I should add external events, wars, droughts, etc. can and do have effects on pricing in this financialized environment, but they are mostly pretexts to drive trading. The tell here is that if the war doesn’t happen, if the drought wasn’t as bad as first thought, if the hurricane veers out into the Atlantic, prices should revert to their pre-crisis levels, but they don’t.

Lucid, unarguable, and exactly factual.

Sounds reasonable. Any way to prove it?

@Hugh Um, you just made a rookie mistake. It is not quantity supplied that determines price, it is price that determines quantity supplied. The supply line is not “screwy”, because in economics the variable is on the x axis, not the y.

“It is not quantity supplied that determines price, it is price that determines quantity supplied”

Do you seriously believe that? Perhaps in some Econ 101 version of the universe. Oil gluts, oil embargoes, bumper crops, crop failures, the post-bubble burst market in housing, there are counter-examples to your thesis that we see on almost a daily basis.

Crude oil doesn’t correspond to this model for many countries. When the price of oil was low, they pumped all they could (forget about sham OPEC quotas) because they needed every dollar they could make. When prices went up, they still pumped everything they could because they still needed every dollar they could make from doing so.

Agricultural commodities don’t fit this model either particularly. Initially they do to some extent but eventually producers/storage operators face a squeeze because new crop will displace old crop. So even if prices drop, they may still be forced to sell more to clear out their old stores and make room for the new.

One further point. The demand and supply lines represent the ‘aggregate’. If supply increases you do not move up the curve. A supply increase is shown as a shift in the supply curve to the right. Similarly, a decrease in supply (say to hoarding) would cause a shift in the supply curve to the left. Econ 101 stuff.

There are a lot of ways I can think of that the futures prices pulls the spot price towards itself, and you’ve mentioned a key cog in one of those machines: relative size of markets.

We’ve even read of traders (meaning of course that they held futures) buying oil and renting tankers and holding the tankers offshore….

etc. etc. etc. This is just one class of influence.

of course, when a trader (speculator) hold a commodity, it helps demand appear inelastic. etc. etc.

There’s no end it seems to the exceptions to the simple theory.

A tight and cogent argument, Hugh, in which I concur.

This issue is being over-analyzed.

While changes in weather will produce drastic swings from year to year, overall global food production is now stagnant and there are no realistic prospects for increasing it. The green revolution is tapped out; we can’t just dump more chemical fertilizer on crops and get more yield; there is not more arable land available; genetically modified foods do not increase net food production.

Because of past government policies aimed at maximizing population growth in order to keep wages low, we are adding about 100 million more mouths to feed each year. And no the problem is not a “growing middle class” – the standard of living in the modern third world is below that of medieval europe (see “British Economic Growth 1270-1870”, by S. Broadberry, B. Campbell, A, Klein, M. Overton, and B. van Leeuwen, 2010) – it’s the increasing numbers, period.

No significant increases in food production. More and more people. By hook or by crook, food prices relative to wages ARE going to go up.

But Krugman can’t really address this because population is a taboo subject for economists. So he has to blame global warming or something, and his arguments must become flawed because the main factors are off-limits.

You are missing the point.

100 million mouths per year is +1.5% per year.

That alone cannot explain 40%+ increase in food prices.

A significantly restricted supply of grains due to

record hot weather in the hottest climate

year on record can.

It’s not that complex of an argument …

What a depressing accumulation of ignorant comments.

Yves made one great point. “This is simply not knowable.”

Of course it’s not.

Yet no one else in this comment thread seems to realize that the fundamental facts necessary to prove their own ridiculous theory on the ***entire*** reason for a run-up in diverse commodities at different times is also simply not knowable.

You know what? Maybe it’s a complex system and there are a variety of factors at play. I know this is an insane proposition from me and has *no* support in the natural, physical world around us (there are *no* complex systems and feeding almost 7 billion people/automatons every day is simple and straightforward).

Wrong. She was pointing to that fact that inventories are unknowable. The mechanics of the futures market on the spot market is, however. She did not get into that part yet, but she will soon.

Yves,

Did you see this econ paper about the oil price rises?

Speculation without Oil Stockpiling as a Signature: Dynamic Perspective – Pierru & Babusiaux (April 2008)

http://web.mit.edu/ceepr/www/publications/workingpapers/2010-004.pdf

I think that paper raises a good point. I wrote a blog post with my thoughts about how it gets to the core of Krugman’s argument. I’d like to know what more people think about it, Krugman in particular.

Actually, I borrowed the link from Fred chez Thoma, so he gets the H/T. Here’s a link to Fred’s site, discussing the paper:

http://stopmebeforeivoteagain.org/2011/02/about_that_signature.html#comments

Thanks John:) I’m glad someone saw that.. I figured that the comment thread at Thoma’s was dead by the time I got to it, and I’ve been having real trouble posting comments and links here on Yves’ site for some reason.

You have any thoughts on the paper?

I’m not that mathed-up or model obsessed, but it struck me as fairly obvious: high short-run demand inelasticities favor specs. The only interesting bit was that that implies a much lower need for inventory accumulations than the “standard model” assumes.

As to the comments on your thread, I hinted at a point chez Thoma, about the role of the oligopolists in price manipulations. Rising oil prices with stagnant NG prices/increased supply serve their strategic interests, in that the “majors” being the same producers, since low NG prices undercut “green” replacements, (especially since NG is the “greenest” of fossil fuels, however environmentally odious “fracting” actually is), whereas high oil prices underwrite bondoogles like Canadian bitumin or deep-sea drilling in, er, the short-run.

Yes, it does seem rather obvious. That’s one thing that I like about it. It’s very clear, simple and — dare I say — Krugmanesque (I’m actually a huge Krugman fan, I just strongly disagree on this issue). Maybe it’s confirmation bias, but it does seem to match the way that I figured that oil pricing works to begin with. Still, it’s nice to see it laid out by someone with a lot more math skills than myself.

The last point you mention about the tar sands is a key one for me. Environmental-leaning people like Krugman sometimes seem to think that any increase in (dirty) energy prices is a good thing, but these rapid price swings seem to mainly result in even dirtier energy being used. I’m Canadian so what they are doing with the tarsands in Fort MacMordor hits close to home. I really don’t think that rapid increases in oil prices are good for the environment at all, especially when, as you say, natural gas prices are still low and are counteracting the impetus to develop green technology.

John, I think that paper makes the same point I was making below. I told people back in the early 1980’s we would see gas at or under $1 again. The Eastern Establishment was pushing the idea of $5 gasoline by 1990 at that time. The difference between the structure of a short run as opposed to long run chart on oil or any commodity can be extreme. I used to call it the 5% rule, where you can create a shortage of 5% in a commodity like oil (the Iran situation in 1979 was such a case) and run the price to double or triple. If one holds enough contracts, they can hoard oil off the coasts and make enough money to pay for what they have in hoard on the futures and never deliver the oil. Below someone mentions the banks, the Wall Street ones. It was a CFTC ruling in the early 1990’s that lets these thieves into the markets. We don’t owe these guys a slice of everything we do in life, but it appears they are taking it. If I had $100,000 and someone came in and took $1000 of it and I called the police and they found the guy, he might do years in prison. Yet Wall Street is taking the same slice every year in gaming the US economy and parading around like kings. They have turned the entire country into their own casino, where they are the house. I would venture no more than 20% of their total gross is legitimate.

Could we say the commodities market is being traded like the housing bubble dirivatives were being traded so that “one bad Harvest” or “a few bad mortgages” could collapse the entire system and lead to food hoarding as it lead to money hoarding and liquidity freezing in MBS market?

I don’t know, but sounds like all markets are manipulated regardless of what krugman says. Evidently he didn’t really get Yves’ lesson on oil speculation even though he adjusted his thesis.

I doubt whether anyone will read this far, but heh…

Prices only determined by physical stocks? – what utter bollocks.

Do these people think no one ever heard about tulip mania?

Why do Krugman and the like continue to spout such crap. Those who are busy looting I’m sure couldn’t give a toss what they say, and anyone else with half a brain would just laugh if they hadn’t been stupefied by the mumbo jumbo.

Long live President Mubarak!

If Krugman had a clue,then he’d have watched the Senator Levin’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations hearings and the CFTC hearings on wheat speculation to know that there were so many futures contracts that it was supposed to take 3years to unwind. These contracts were also in “full carry”. The CFTC implemented some remedies for grain operators and distribution (making it more expensive to store, and insure grains), but it’s taking more time.

The SEC is also investigating ETFs for insider trading…Yves Smith…thanks for highlighting points which should be quite apparent to Dr. Krugman.

Price parity. This is something entirely missing from this discussion, as far as I scrolled down. I have spoke with farmers and read their publications and my conclusion is that Yves is getting the point better than Krugman. As I recall Mr Kaufman anecdotally recalling his early banking years, when he had to actually go out to warehouses to visually inspect rolled steel inventories. This was opposed with taking meetings, conference calls, presentations of the dog and pony variety and reliance on statistical abstracts.

Amazingly enough, across the street from Berkadia Capital, nee GMAC Commercial, is a large farm regularly exploding with corn every summer. Driving further west of Philadelphia, you see a lot farmers planting corn. My insider info tells me that they don;t plant this for their health. And if you hold your gaze you will see the large cylinder grain silos, in addition to barns.

But back to price parity. Rural, farm society decoupled from the urban metro society where most of now live, a long time ago. The war of farmers with the food processors, the distribution system, the supermarkets, and on and on has been fought out in Congress by competing business interests and only came to some satisfactory conclusion during the NEW Deal. What is now derided as corporate farm subsidies is a political accommodation between farm and urban societies, as they operate in the modern world. To see this world view, you would have to read about farm price parity issues. Looking at food as a commodity screams your urban bias.

I remember when the government/system payed small and medium farmers not to grow[!] hahahahaha.

PA is an insignificant corn producer, about 1% of US production. And the vast majority of the crop is used for silage for livestock.

Seeing a silo on a farm in PA and believing it is being hoarded is beyond silly.

The Christian Science Monitor has the comprehensive take on the scope of the problem. Sure, speculation and Bernanke’s QE are part of the story. But some other planetary-scale chickens are coming home to roost.

http://www.csmonitor.com/Commentary/Global-Viewpoint/2011/0208/Brace-yourself-for-the-food-price-bubble

“If the world has a poor harvest this year, food prices will rise to previously unimaginable levels. Food riots will multiply, political unrest will spread, and governments will fall. The world is now one poor harvest away from chaos in world grain markets.

“Over the longer term, expanding food production rapidly is becoming more difficult as food bubbles based on the overpumping of underground water burst, shrinking grain harvests in many countries. Meanwhile, increasing climate volatility, including more frequent, more extreme weather events, will make the expansion of production more erratic.

“Some 18 countries have inflated their food production in recent decades by overpumping aquifers to irrigate their crops. Among these are China, India, and the United States, the big three grain producers.

“When water-based food bubbles burst in some countries, they will dramatically reduce production. In others, they may only slow production growth. In Saudi Arabia, which was wheat self-sufficient for more than 20 years, the wheat harvest is collapsing and will likely disappear entirely within a year or so as the country’s fossil (nonreplenishable) aquifer, is depleted.

“In Syria and Iraq, grain harvests are slowly shrinking as irrigation wells dry up. Yemen is a hydrological basket case, where water tables are falling throughout the country and wells are going dry. These bursting food bubbles make the Arab Middle East the first geographic region where aquifer depletion is shrinking the grain harvest.

“… the largest water-based food bubbles are in India and China. A World Bank study indicates that 175 million people in India are being fed with grain produced by overpumping. In China, overpumping is feeding 130 million people. Spreading water shortages in both of these population giants are making it more difficult to expand their food supplies….”

There’s more.

Krugman is very careful with words

That’s why he refers to evidence

You suspect the evidence is incomplete

No conflict there

Gretchen Morgenson of NY TIMES (Sunday editorialist) pointed out in September, 2004, that Goldman-Sachs held 13.8% of total worldwide “energy futures”, and that Lehman Bros, JP Morgan, Bear Stearns, etc, owned somewhere less-around 7%. These “investment banks” had been trading these

back and forth, price rising at each trade-nice work if you can get it, and if an unscrupulous Bushit administration places industry cronies in positions of “oversight”.

In August, 2004, she shows that Goldman sold off 1/3 of total energy futures. Others, who had been involved in the ponzi scheme blinked. Goldman stated that the next month or two, they would buy back in, in “blended fuels” or bio-diesel. By the way, this sort of monopoly-collusion has been going on on Wall $treet since the 1800’s=Geisst’s book,

“Wall Street-A History”.

In September 2004, Goldman sold off another 1/3 rather than buying “blended fuels”, and the others panicked and sold also…just in time to bring the price of gas down from around $4.00 a gallon (it was around $1.00 a gallon under Clinton-when he left) to $2.00 a gallon, just in time for November, 2004 Bushit re-election…

as they say in Matewan, “Draw your own conclusions..”

Congratulations Yves, this post is one of the Top 10 IMHO.

This being said, I am not sure you understand (or at least you stress enough) why Krugman will NEVER accept your point of view :

Krugman does MACRO economy, that relies on the analysis of aggregates. If the raw data happens to be wrong, it becomes a “garbage in – garbage out” exercise, nothing more. Therefore, even if his models are, in his own words, “buttoned down” (and they indeed are), they become practically useless.

In short, you are indirectly attacking what he thinks is his social purpose : enlightening us mere mortals on how we should drive our economical affairs. He is too personally and emotionaly invested in this role to ever recant. It is like showing MDs statistics that demonstrate that their procedures don’t improve the health of his patients : they – and their patients ! – simply refuse to believe them.

Ironically, Krugman himself recently referenced a paper produced by the American Economic Review for its 100th anniversary, that lists its 20 best papers. The second paper, chronologically, referenced is this one : http://www.aeaweb.org/aer/top20/35.4.519-530.pdf and states the problem very clearly. This other paper that nails the coffin is http://www.aeaweb.org/aer/top20/70.3.393-408.pdf . Why anyone could really trust statistics after reading these is indeed the stuff psychology and social studies are made off, but certainly not macro-economy.

I’m not out to persuade Krugman (and he’s taken this position so consistently for so long I don’t see how he can back down). I’m speaking to the people who aren’t sure what to believe on this topic.

Re the pdfs. When the arbitrage becomes orders of magnitude larger than what is being arbitraged, I’d have thought you’d be better off reading Minsky than Hayek. I didn’t know anyone could still cite Hayek with a straight face.

Good article Yves. I think commodities are a bubble. I also believe Krugman runs resistance for NY Bankers with the best of them. I have yet to see anything come from him that at least indirectly doesn’t funnel money in their direction.

The funds are the ultimate bag holders. I have examined how commodities work over a period of years. Most bull markets have a corner associated somewhere with them. I believe copper has been cornered for years, at least since the mid 2000’s. The real estate business around the world is on its ass. China hasn’t accelerated that much to cover up what isn’t being done in the US and Europe. Oil supplies in the US, when I checked in December, were roughly 11 days supply greater than 2007. I have followed oil for nearly 40 years and since 1985, the norm for a supply situation as this is a break in prices. I did a little trading on the oil exchange last year and it was apparent to me that there were machines that were moving bids and asks in a fashion to move the price in a particular direction. The norm for buyers and sellers of a market is not to drive the price up or down, but to buy as low as possible and sell as high as possible. Thus a buyer wouldn’t normally be trying to buy at a higher price. It was clear in watching this was the case. Copper was quite amazing and looked like a rugby game.

The commodity funds are really mind blowing. There is only one way these entities can play commodities and that is to hoard them. As more money builds up in these funds, the hoards have to increase. It doesn’t make any difference what the market is. But, in time, storage costs mount up and so does supply. I think we saw this with coffee in the past decade, where the cartels were piling it up in an attempt to support the price. Despite the hoards, it took this bubble to finally move coffee.

The supply and demand chart krugman put up is a long run chart. In the short run, supply can always be squeezed by a corner. Buy more than can be delivered and take delivery of just enough to make the profit in the surplus contracts. This in essence gives a discount in what is delivered. The insiders can also sell their excess to the public traders who are playing a move. The public always has to exit. The commercial doesn’t but I recall the large firm that managed prices for independent oil companies in 2008 being driven to bankrupty through the massive push to $147. The prices moved more than they could post collateral and they were liquidated at the top. The big problem is the outfits like Goldman Sachs are being allowed to play in markets where they know the position of the other traders. It is like playing poker with a mirror on the opponents cards, a rigged game.

I always heard it was called ‘cost push inflation’ (think QE 1,2,3..) and it has been fairly orderly. Meaning the speculators or the ones that don’t really buy to consume haven’t arrived yet ex. Red China buys commodities because it needs them, speculators buy to corner a market and spike the price. Consumers like farmers are just caught in the crossfire.

Things you don’t need deflate while necessities take priority and rise in costs thanks to excess money looking for return on investment.

http://bigpictureagriculture.blogspot.com/2011/02/debunking-krugman-nyts-soaring-food.html

“The most important food commodities which determine food security for human consumption are rice, wheat, and corn. To summarize, right now we have comfortable global stocks of rice and wheat, but we are extremely short of corn in the #1 global corn exporting nation because that nation is using well over a third of its corn production to fuel its cars.”

“Krugman: Back to the economics: if you want to know why we’re having a spike in food prices, the data suggest that the key cause is terrible weather leading to bad harvests, especially in the former Soviet Union.

Kalpa: You really scared me with that sentence. If I wrote something like that I’d lose every reader that I have.

Since you like talking economics, besides supply and demand, major causes of high food prices are individual national food policies and currency conditions. The Asian nations are experiencing food inflation because they are experiencing high overall inflation. Poverty levels, subsidizations, tariffs, setting bread or fuel prices, devalued currencies, import and export restrictions, infrastructure standards of food storage and transport are all important factors in food prices which help determine levels of food security within individual nations.”

Economics using 2 dimensional graphs…cough…modeling a chaotic man made universe aka electronic trading platforms (lol unknown unknowns!) with ONE axis…really? Yet to fight this voodoo an order of math must be applied that only a small percentage of the worlds population can grasp…mon Dieu!

Skippy…increases in complexity, in short time frames, is the mother of all risks[!] no time for the dust to settle and observe.

You have a point but your line of reasoning raises as much question marks as does the reasoning by Krugman. You moved to a grey zone with guesses, something Krugman handily avoided and you pointed out rightfully he did.

First we would need to distinguish between all sorts of private players. We have the commercials (factories) who can build inventories as a safety net but II wouldn’t call them speculators (it’s a kind of hedging although most will use financial means), financial speculators who will in general not invest in the physical commodity and traders who can withhold the stock (big ones like Dreyfus). Only the latter can have a significant impact on the spot price.

Agri producing countries with obscure statistics can equally play on this ground and bad weather and fires can be used as “valid” reasons to further manipulate the prices in their favor or even try to trigger political events.

A second task is to define what kind of speculation we target. Do we talk about financials/derivatives or about hoarding the commodity?

As Krugman pointed out, and I think this was the main thread in his reasoning, derivatives have no (I would say a negligible) impact on the spot prices. Something that has been contradicted by a EU report recently but contains on this subject nothing more than utter nonsense.

Last my personal thoughts.

For hoarding to be successful there has to be a shortage of the commodity or a near-shortage. Traders can only drive up the price when they only need to hoard marginally. The size of the agri market, the limited players in this market, the long term commercial relationship that has to be respected between producers, commercials and traders, the global nature of these markets, and more, make it rather difficult to hoard massively and influence the spot prices.

In this context I don’t think your reasoning makes much sense.

Hoarding can also be the act of *not producing* or diversion from traditional usage, bio fuel, live stock feed, et al. These things can be very hard to discern from a harvest prospective, yield expectations, cough macro observations.

Skippy…you have the granular optics or you don’t, there is no in-between, save posturing.

In 2009 European steelmakers cut production to lift prices and there still many more factors of influence. Everyone can invent one.

I even think that hoarding by traders or countries is accompanied by unhoarding, or rather lower inventories by commercials.

Krugman is living in a world of his own invention on this one. His position is fairly simple: since the markets in question are too large to be speculatively driven, and hoarding is not much in evidence, therefore the price must be and can only be demand driven. Wonderful theory, but his framing of the problem is defective. Leverage bets, contract tiering, and chokepoint bid-ups do in fact make it possible for large players in concert to squeeze the markets. He doesn’t want to believe this is possible, so he just turns his back to the facts and keeps drawing chalk scribbles on the board. This is a man who has never traded a contract in his life, and really doesn’t understand how markets work off the page and on the floor . . . .

It is kind of humorous that the side favoring the “speculators did it” is basing its discussion on speculating on the amount of stocks.

I agree with this:

“That is not where our bone of contention with Krugman over oil in 2008 or our reservations now lie. It’s over statements like this:

But for food, it’s just not happening: stocks are low and falling.

This is simply not knowable, or at least not to the degree of confidence that Krugman has.

One thing I do on a regular basis is analyze information about market size and activity, and over time, it’s taken place in a very wide range of industries (yours truly specializes in oddball deals). Unless you are dealing with markets in which the government demands extensive reporting (like Japan, the data you can get in Japanese is just fantastic) or ones where you have a system of centralized reporting or other tight controls (like pharmaceuticals), it is very difficult even to get decent estimates of market size. So a basic issue is: understand the integrity of data.”

The problem starts when those stocks are speculated to be more than Krugman says. And listing places where the stocks could be(“storage facilities by private owners (major refiners such as flour mills), finished product, private speculators (there have been reports for years of base metal stockpiling in China), even the consumer level”) reminds me of George Bush at the Press Club “looking” for WMDs.

Yeah, they certainly could be in all and/or some of those places. But there is no “intergrity of data” merely by listing possible storage sites.

Ultimately, this seems to be a question not about whether financial (as opposed to commercial) speculators entered commodities futures markets in a big way (agreed), nor whether they did so through largely deregulated financial instruments (they did), but about whether all that new money provides added liquidity to futures markets, with no ill effects. That seems to be Krugman’s argument, because in the end it’s all about the physical commodities. But doesn’t all that financialization make a mess of price discovery? After all, why are some of the most vocal groups that are demanding reregulation and strict derivatives reforms the commercial hedgers themselves? To listen to Krugman, they should be thrilled that Wall Street is throwing money into their markets. From what I can tell, they’re not. And that makes a whole lot of sense if futures markets actually affect the decisions of economic actors in the real world. Guess what: they do, from farmers deciding what to plant to governments deciding what to buy, like Mexico locking in a contract on corn futures now in fear of another price bubble. A “panic buy?” Maybe, maybe not. It all depends on how reliable the price signals are in the futures market. Financialization makes a mess of that.

“Financialization makes a mess of that.”

well said. the key issue here is leverage, i.e. the size of the debt-fueled derivatives monster relative to the underlying economy. this is the shadow money supply that drives prices higher. if you want to understand the price of any commodity or asset, you must not only look at the supply and demand of the commodity, but how it interacts with the supply and demand for the monetary unit in which it is priced.

we call this the tail wagging the dog. the USD denominated debt market is so large and unstable, that on the margin it can overwhelm the supply-demand dynamics for any good. recently, Ben Bernanke took credit for pumping up stock marjet prices while simultaneously claiming that QE2 had no effect on food prices. think about that. the chief central banker in the world is brazenly lying in public.

it is past the point that Yves or any of the other well-meaning bloggers ought to be engaging Krugman or any of the other mainstream apologists anymore. just stop Yves. it’s a waste of energy debating them. it only reinforces their frame and lends them validity (see George Lakoff). to paraphrase Jesse, until the banksters are taken to the woodshed, it will only get worse. unfortunately, this is in the invisible war and it’s about how money is created. we need to cram down leverage everywhere. it’s the only way to ensure any semblance of “price stability”

**Love** the graphic. I drew one just like it many years ago while puzzling out the bullshit in undergrad econ (my first and last foray into such orthodox nonsense).

Has anyone devised a name for the gray area between inflated price and supply/demand? I propose ‘offshore accounts.’

State of debate:

Yves Smith argued that Paul Krugman’s commodity speculation criterion – accumulation of commodity inventories – is not knowable with a sufficient degree of confidence. But if the criterion is not falsifiable (Popper), it is worthless.

Moreover economists Axel Pierru and Denis Babusiaux argued in a recent study: “… speculation may temporarily push crude oil prices above the level justified by physical-market fundamentals, without necessarily resulting in a significant increase in oil inventories” (link provided by commenter john c. halasz).