I hate to take issue with a post by Mike Konczal on some Dodd Frank reform ideas posed by Charles Calomiris in “Beyond Basel and Dodd Frank“, since Mike is usual a source of reliable analysis. But that’s why it’s particularly important to let one of the rare times he goes off beam not to lend credence to reform ideas that are sorely wanting.

The problem in general with Dodd Frank and subsequent fixes is they don’t come close to doing what needed to be done, which is dramatically reduce the ability of financial players to wreck the economy for fun and profit. The fact that the banks howl bitterly over some half-hearted measures should not be mistaken for effectiveness. The big dealer banks have realized that they’ve emerged more powerful, and better able to extract rents, than before the crisis, so why not press home their advantage? Their new position is that any restriction on their profit-seeking is an intrusion and should be beaten back. Witness some recent evidence: their foot-dragging on clearinghouses for swaps. The normally accommodating New York Fed is forming a group to “compel” the banks to live up to their commitments. Of course, with enablers like Timothy Geithner, who has signaled that he is leaning toward exempting foreign exchange derivatives from Dodd Frank implementation, the banks don’t have to fight all that hard.

Let’s turn to the current debate. The proposal comes from Charles Calomiris, but I’m going to deal with both the Calomiris paper and Konczal’s reactions to it. In general, I’m leery of the drift of this limited scheme because it fails to address the elephant in the room: that of the tight coupling within the financial system. Undoing the tight coupling as much as possible has to be the top priority. That’s why some form of Glass-Steagall-like modularisation of retail and investment banking is still under discussion in the UK. That’s why banks’ holdings of each others’ debt and prefs deserves closer scrutiny. That’s why moving from a home-country-dominant regulatory regime to a host-country-dominant one might help. That’s why one would like to see more instruments traded on clearing houses and exchanges, to the extent either is a viable solution: neither works well with the sort of complex, hard to value instruments that too often wind up being highly profitable, toxic “innovations”. Short of those sorts of changes, and others, in a tightly coupled system, measured designed to reduce risk frequently increase it.

I’m also leery of the Calomiris paper simply because he proceeds from false premises. His analysis is based on a story of what went wrong in the visible, regulated banking system, when the real problem was its significant exposure to and involvement in the largely unregulated so-called shadow banking system, which we defined in ECONNED as:

• Securitization (and other off-balance-sheet vehicles)

• Repurchase and reverse repurchase agreements (otherwise known as repos)

• Largely unregulated insurance contracts on debt securities (credit default swaps or CDS)

His failure to do an adequate study of crisis mechanisms makes his recommendations badly off base.

Let’s consider the Calomiris’ ideas. This is the first:

Use loan interest rates when measuring loan default risk.

That’s a terrible idea unless you get rid of CDS and securitization, which no one is prepared to do (we’ve recommended that CDS be strangled over time to being much less influential; they’ve become so integral that a ban and a run off would produce dislocations). Calomiris’s support for this idea comes from a buy and hold notion that is inoperative in most areas of credit extension (and don’t tell me about the 5% risk retention rules; we’ve argued that it’s too small a percentage to change behavior ex other changes, like being required to hold loans a full year before they could be securitized, which were omitted).

As we have discussed at LENGTH on this blog, the use of synthetic and heavily synthetic CDOs from late 2005 to 2007 produced massive distortions of subprime loan pricing. The dressing up of BBB bond risk so it could be sold substantially as AAA paper (priced at more like AA spreads) served to distort normal pricing mechanisms. The high level of short demand created superheated demand for not only BBB subprime bonds, but the very worst BBB bonds.

And more generally, you have CDS spreads which determine bond prices which influence loan spreads. Price discovery occurs in the CDS market, which is less liquid that popularly imagined (only 50 or so names trade actively, but like the old gridded corporate bonds, they are still important pricing benchmarks). Nevertheless, the people who price CDS don’t do deep credit analysis. It’s a prediction market of sorts, and as anyone who has studied prediction markets will tell you, a prediction market simply reflects the expertise and knowledge of its participants. They can easily be garbage in, garbage out exercises.

His second idea:

The SEC should reform the use of credit ratings to require NRSROs to estimate the probability of default, and provide that number as their rating for regulatory purposes, rather than give letter grades, and then hold NRSROs accountable for the accuracy of those estimates.

This is naive. There are too many products and regulations make specific reference to ratings; the amount of revision of regulations at the Federal, state, and local level, as well as in private contracts, would be enormous. The SEC can’t do this in a vacuum, and there are too many parties who want the risk cover of a rating who will fight getting the needed consensus.

But even if it were not naive, I don’t see this as viable. Konczal argues that the ratings agencies have implicit one year default estimates, but that isn’t even quite accurate; he implies (perhaps unintentionally) that the implicit default rate is the same across products when it isn’t. That had been the intent, but in the early 1990s, default ratings became more and more issuer-specific (recall the controversy that municipalities were graded tougher than corporates).

And going from a one year default to a five year default estimate is like saying that because you can fly a plane, you can also fly to the moon. Equity analysts don’t forecast beyond 18 months for good reason: it’s pretty unrealistic to do so. Admittedly, equity is a residual and hence riskier, but I’d hazard that the ratings agencies would argue, with considerable justification, that five year estimates would be so broad for anything other than a very narrow classes of very stable issuers like utilities as to be useless for practical purposes. This is the sort of exercise that would make Taleb scream: trying to achieve illusory statistical precision over time frames that render the practice sorely misguided.

Where this sort of notion is most misguided is in an area Calomiris and Konczal omit, and was again central to the crisis: products with high embedded leverage, such as CDOs. As Joe Mason and Josh Rosner discussed in a 2007 paper, “Where Did the Risk Go?” CDOs were inherently susceptible to multi-step downgrades, and we saw that happen dramatically in the crisis, as AAA CDOs were literally downgraded to CCC (junk) in a single day. Now Calomiris and Konczal might argue that that sort of risk would show up in a five year distribution, but I beg to differ. You’d need a three dimensional analysis to show the risk of a multi-class downgrade.

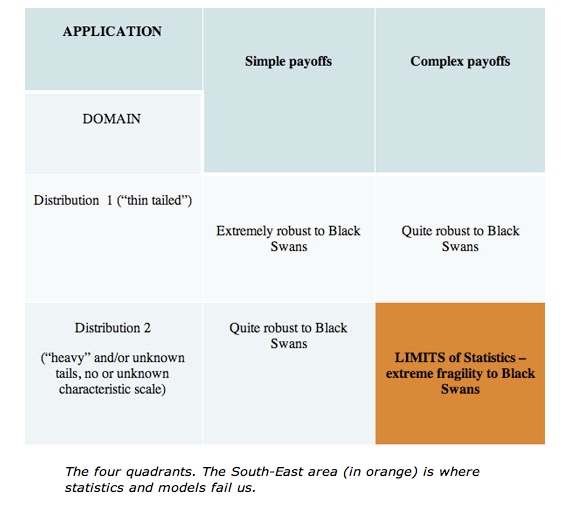

And more basically, banks and investors continue to rely on statistical methods (which is the subtext of the approach advocated here) when banks find their most profitable ones to be products with high degrees of complexity. They allow fees and risks to be hidden from clients, but they result in exposures that are are not accurately delineated by statistical risk estimates. From Taleb’s paper The Fourth Quadrant:

Oh, and those same orange exposures don’t belong on exchanges either, since they can’t be margined reliably.

Calomiris’ next point advocates contingent capital certificates, or “cocos”, which convert from debt to equity when certain thresholds are met. Richard Smith has been planning to post on them so I will leave this important topic to him.

Calomiris’ final suggestion is:

Limit the extent of discretionary bailouts of creditors under Dodd-Frank. As noted above, the Dodd-Frank bill makes unlimited bailouts of creditors possible. This is a mistake that could be easily corrected by explicitly limiting the protection of creditors to no more than “x” percentage of their principal. Even if creditors knew that only 90% of their principal was protected, that would provide a powerful incentive for them to be careful about the riskiness of the banks in which they invest.

There are numerous flaws in this reasoning, the biggest being that creditors who are exposed will be exposed to only one isolated player, and can monitor them adequately. The ugly truth is no one knows how to evaluate the riskiness of a major dealer bank. Their exposures are impenetrable. The whole premise, that investors can judge the risks of anything more complicated than a purely domestic, traditional commercial bank (retail banking and institutional lending, no fancy footwork in its Treasury operations) is garbage. In fact, no one with an operating brain cell should be a creditor of a major dealer bank ex the now explicit but denied state guarantee, since it’s otherwise faith based paper.

The second wrongheaded hidden assumption here is that a creditor is exposed to the failure of only one player. But as Andrew Haldane and Robert May discussed in a recent Financial Times comment, big financial players are not diverse. You have many very similar players (who copy each other’s products, fight to be all things to all customers), which means if any one gets in trouble, the others are likely to suffer precisely the same affliction. You won’t see one party wobble in isolation, you’ll see them all under duress. And because all are thinly capitalized (and even more so when under stress) losses at one will impact the others, leading to more writedowns that will cascade again through the system.

And some players are central and loss intolerant. Money market funds, which are critical providers of deposit equivalents, still maintain their $1 net asset value promise, which was considered to be so important that they got emergency Federal guarantees. Has anything been done to get investors to understand that they shouldn’t rely on a promise from not terribly well capitalized asset management firms? in the wake of the run on mutual funds when The Reserve Fund got in trouble as a result of holding Lehman commercial paper? Similarly, having bank preferred stock holders take losses was off the table because regulators had encouraged smaller banks, who were also in trouble, to buy the preferred stock of other banks. Again, this was effectively doubling up on sector risk, and increased fragility. Do we have any reason to think we won’t see similar poor decisions down the road?

The third faulty assumption is that Calomiris argues about “investors” when it wasn’t “investor” losses that produced the financial crisis, it was losses among highly levered and deeply integrated counterparties. And at Lehman, the losses were greater that 10%. Even if you generously assume $30 billion of Lehman’s $135 billion in losses was due to the chaotic nature of the collapse (my derivative experts who are involved directly in the Lehman bankruptcy say the actual number is unknowable, but the Alvarez & Marsal $50 to $75 billion figure is simply wrong), you get 16% losses on its $660 billion balance sheet. The run on Morgan Stanley’s liquidity pool suggests it might have failed too. If you imposed another 10% losses across the system, who else would have come up short? Banks are simply not going to fail in isolation in our current system.

The problem with these ideas is that they are inadequate. And relying on inadequate measures simply produces an illusion of safety that leads to complacency. It’s like driving a car with faulty brakes. You increase the odds of an accident if you convince users that they are fine.

I’d rather see more focus on how risky the current the system is (and it is still very risky) rather than at patchwork measures which have decent odds of making matters worse. Initiatives like those under consideration in the UK, of breaking up the banks, are more consistent than what we need to do than this sort of rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Friends;

What hope of avoiding another financial meltdown do we have if the previous crisis was essentially finessed by the ‘big players’ on the street? The numbers don’t lie, certain behaviours inevitably lead to disaster. Right now, it’s sort of like an alcoholic being able to make someone else have the hangover. Until we as a society decide to focus the pain back on its’ source, nothing will change. Have a rational day!

Yves, I can only add this to what you’ve said about inadequate risk measures: we lack the tools and modelling is intrincically unreliable. See (you may have missed this, which made me laugh out loud): http://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/2011/bulletin-2011-12.html. Didn’t work too well when worrying about metal fatigue on Boeing 737s either, did it?

Wow. Failure to understand model results, the limitations of those results or, as was far more common during the crisis, willful misapplication and co-opting of model results does not imply that all quantitative/financial modeling is inherently unreliable.

This type of guidance is long overdue. Banks need to be aware of the risks inherent in any quantitative/analytical exercise they undertake and develop processes and procedures to bring potential risks to the attention of those utilizing model results to inform their decision making.

The only thing funny about the release of this guidance is that the document has been largely complete for a year while individual mid-level executives in all the agencies, with zero modeling expertise, put their finger prints on the final document. All the while, the memories of what can happen in a crisis, even to good banks, have faded.

I don’t see how breaking up the banks would help much or at all. If they are all still tightly coupled or corelated or all copying each other’s behavior or all lending to one another, selling loans to one another they will still all colapse together. If AIG had been divided into ten smaller pieces would it have made any difference?

There’s more than faulty reasoning in progress. There’s the fact of pandemic unprosecuted fraud.

Dodd-Frank is weak on fraud and because with fraud prosecution most of the primary dealer banks be exposed and there would be the call for splitting them up. Now more than a few of the primary dealer banks are global in their reach so in that you would sovereign regulations to contend with.

More than anything this entire financial collapse is about the fiat currency/fractional banking system which is global in its reach. The fix is internal and not external. If the Dollar is to continue as the global reserve currency it will have to become redeemable for something of inherent value or something that fairly represents inherent value.

That consideration would lead to a very substantial increase in the price of gold and/or its monetary equivalent. That equilibration would then destroy the labor cost arbitrage that makes the movement of US jobs off shore feasible.

1.3 Billion is very much larger than 300 million. In that differential there is the question; Is it reasonable to assume that the US can remain the hegemon of consumption?

These are considerations that fairly show that Dodd-Frank is papp, palaver and platitudes in the first place and that Calomiris is a straw man looking for a fire.

The big dealer banks by no means have emerged more powerful. I don’t understand with confidence shattered as it has been, how over-leveraged behemoths now revealed 100% bona fide vulnerable could ever emerge “more powerful” with fantasy’s perpetuation in a Congress of jellyfish. These banks would be more powerful only on one condition: if they willingly submitted to the most stringent regulation. That they will not but further exposes the likes remain 100% bona fide vulnerable, at risk of run, blown up, hopelessly insolvent, “assets” destined to turn to the fiction they are: fucked.

Forget about the tight coupling. The only coupling fast coming to matter most is that which connects debt to its legitimacy. That debt which kills is illegitimate. There is an ocean of it and that of it which is fully backed by the U.S. Treasury must be decoupled: written off. Thus, tens of trillions are involved.

“Powerful” means politically powerful. Look at their industry concentration, the gutting of reform efforts, and top executive and producer pay in 2009 and 2010.

“models”..doesn’t mention fact regarding “computer” inputs,

which we recently learned Goldman-Sachs, for example, can utilize to create 30 million trade-shares per minute…

which “justifies” in their minds, monopolizing-driving markets through speculation..as they are not “end users” of energy-commodities they are moving in such numbers…

All discussions of risk and regulation in capital markets are ideological fiction dressed up in mathematics with the intention of extracting perpetual rent. All those indulging in this exercise are criminal conspirators, which makes them no different than celebrity executives buying and bamboozling stooge directors, pontificating politicians, tort lawyers advertising on television, toadying media commentators, other assorted shysters. Nobody knows how long the game can continue, but the identity of winners and losers is crystal clear. This is class struggle and Warren’s class is winning, as he freely admits.