Yves here. I’ve long been interested in the German approach to housing, since it has two noteworthy features: very high rates of rentals and reasonable costs. This post from MacroBusiness provides a short but very instructive overview. I’m intrigued to see this article highlight an issue that I have stressed as a New York City resident, where tenants have much stronger rights than almost anywhere in the US: that strong tenant protections actually help landlords. The result is that people rent not because they can’t afford to own (which means they are financially less stable) but because they prefer not to (for instance, they prefer the flexibility, or decided to put their money in a second home or in investments). And tenants who have property rights (as in the landlord cannot deny them a lease renewal if they are current on their rent) not only take better care of their unit, but I’ve seen them actually make meaningful investments in them (this happens a lot in my building).

From MacroBusiness:

A few months ago, after posting numerous articles advocating the Texan approach to land-use planning, I promised fellow MacroBusiness blogger, The Prince, that I would undertake an analysis of the German housing system, which is regarded as amongst the most affordable and liberal in Europe.

In my findings presented below, I have compared and contrasted the German housing system with that of the United Kingdom (UK), which is considered amongst the most unaffordable and supply-constrained markets in the world.

You will see that German and UK housing policies are polar opposites, with the former providing highly responsive housing supply, significant rental controls, and tighter credit regulations compared with the latter.

Before I kick-off, consider the following broad indicators relating to the German and UK housing markets.

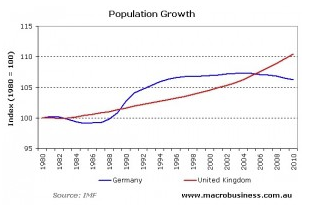

First, real house price growth:

As you can see, German housing values have been stable but falling since the 1970s, whereas UK housing values have experienced four boom/bust cycles and deteriorating housing affordaility (indicative of unresponsive supply) since 1970.

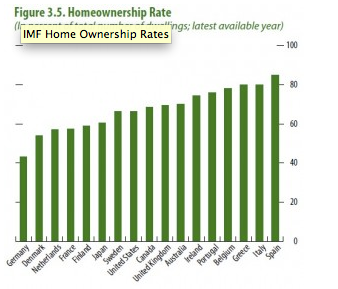

Second, consider the rate of population growth in both countries:

After experiencing higher growth in the 1990s, Germany’s population has grown more slowly recently.

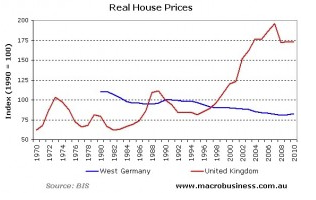

Finally, consider home ownership rates in the two countries:

Whereas Germany has one of the lowest home ownership rates in Europe (just over 40%), the UK has one of the highest (around 70%).

There are three main factors that seem to account for Germany’s stable and lower home prices and lower home ownership rate: (1) responsive housing supply; (2) secure rental tenancy; and (3) more regulated mortgage credit availability.

Housing supply

Germany has some distinct features that enables it to provide a plentiful supply of housing in response to increasing demand.

First and foremost, the German constitution contains an explicit ‘righ-to-build’ clause. According to The Policy Exchange:

…this “means that everyone is entitled to a permission to build on his or her property as long as there is no explicit legal rule against it.

…if the proposed building fits into the plan, permission has to be granted and if the local authorities deny it then a court will enforce it…

Although there is very close control of what can be built on any site, provided it meets the requirements of the master plan, a developer just can get on and build new housing without seeking development permission.

Most importantly, the local governments that control the planning process have a direct financial incentive to provide land for housing, since they receive grants based on the number of inhabitants. Therefore, encouraging development is an important way for local politicians to increase their budgets.

Now compare the liberal German system to the centrally planned approach in the UK, which has for decades explicitly constrained the supply of land for development.

First, UK cities are surrounded by strict ‘greenbelts’ (similar to urban growth boundaries), which prevent development past a certain point. These greenbelts have significantly restricted the availability of land for development, helping to push up prices.

Second, and related to above, the overriding planning objective in the UK has been ‘urban containment and ‘densification’. There is now a target that 60% of all land for housing should be brownfield land – i.e. land which has already been developed for some other purpose – which necessarily means the restriction of land supply and higher land prices.

Third, any change from the status quo – such as a change in land use from rural to urban, housing to office, or an increase in housing size – requires planning permission.

Finally, the UK operates a centralised fiscal system, whereby local authorities – which are the primary decision makers on development and have statutory obligations to provide services for new houses – receive very little revenue from increased population and housing. As such, these local authorities tend to oppose development.

The divergence in home construction rates couldn’t be more stark, as recently summarised by Dr Oliver Marc Hartwich in Business Spectator:

Over the past forty years, both the UK and Germany experienced similar population growth, almost identical decreases in household sizes, and comparable economic growth. Besides, both countries have similar population densities.

Summing it up, the UK and Germany share all the factors that explain housing demand…

However, as comparable as they are with regard to housing demand, they are wildly different in terms of housing supply… The Germans built more houses than the British, both in per capita and absolute terms.

The EU collects data for the housing markets of its 27 member states. According to their statistics, Germany’s rate of dwellings completions per 1,000 inhabitants was consistently higher than the UK’s. In some years the difference was only 10 per cent, in others more than 110 per cent.

The differences in completions were also reflected in the land made available for development. The Cologne Institute for Economic Research calculated that last year there were 50 newly developed hectares of land per 100,000 population in Germany but only 15 hectares in the UK.

Rental system

The German rental system is another key factor contributing to the stability and affordability of the housing market. While the majority of rental dwellings in Germany are private, rents are regulated and prices are prevented from increasing sharply. Tenants also have security of tenure as long as they pay the rent and behave well, except on the rare occassion when a member of the landlord’s family needs the accomodation or when the building is going to be replaced.

Further, because renting is the dominant housing choice in Germany, the political system is highly sensitive to tenants’ rights and perecived threats to the status quo typically receives prominant media attention and political responses.

Since home prices are relatively stable (owing to liberal supply) and renters enjoy secure tenure, Germans have little incentive to rush into owner occupation. As such, Germany doesn’t suffer from the ‘panic buying’ and speculation often present in bubble housing markets.

In comparison, the UK rental system could not be more different. According to the RICS European Housing Review:

The UK now has probably the most liberalised housing sector in Europe since the 1989 abolition for new tenancies of previous controls. There is only limited security of tenure for the first six months of a tenancy in the most common types of rental contract and rents are freely negotiable…

The typical rental property is a terraced house in an outer or inner suburb of a town or city. The property will rarely be new: only 13% are post-1985, and almost two-thirds are pre-1945, although most will have been recently modernised.

And because of the volatile nature of UK home prices (caused largely by supply constraints) and the lack of security of tenure in the rental market, ’panic buying’ from first-time buyers and investor speculation is prevelent when house prices are rising, adding to price volatility:

House price expectations influence tenure choice. Periods when rising prices are expected encourage households to enter owner occupation and the opposite occurs when prices are expected to stagnate or fall. Demand cycles for owning and renting consequently tend to vary over time. Currently, more people are renting because of expectations of continuing falling prices as well as because of greater problems in finding mortgages and raising deposits.

Availability of credit

Mortgage finance in Germany is also conservative relative to most economies that have experienced housing bubbles. According to RICS:

…credit availability is more strictly rationed in Germany compared with the pre-financial crisis experience in many other countries. For example, there is conservative loan appraisal, no sub-prime segment and thorough vetting of loan applicant details.

Moreover, base loan-to-value ratios (LVRs) from mortgage banks (the main provider of home loans) are capped at 60%, although other unsecured loans are often added into loan packages (at higher interest rates), which tends to increase the overal LVRs.

In contrast, the UK mortgage market was fully deregulated in the early 1980s. During the height of the 2000s credit/housing bubble, UK lenders were offering 100% plus LVR (i.e. no deposit) mortgages to first-time buyers. However, since the onset of the global financial crisis, lenders have rationed credit and required higher deposits (reduced LVRs), thus contributing to the boom/bust cycle inherent in the UK housing market.

Conclusion

The contrast between the German and UK housing markets couldn’t be more stark.

Unlike Germany, the UK housing market is essentially a bubble factory. Wheras Germany’s highly responsive supply ensures that extra demand manifests itself in rising new home construction rather than increased prices, the opposite is the case under the UK’s restrictive land-use policies.

The UK’s deregulated rental market and lack of tenure has also ensured that renting is a second rate option, thereby encouraging residents to strive (and borrow big) for owner occupancy. And of course the UK’s lax financial system has been only too happy to oblige, providing households with no deposit mortgages during the boom followed by rationed credit during the bust.

When all these factors are combined, is there any wonder why Germany’s home prices have remained stable and affordable, and free of the speculative behaviour, ’panic buying’ , and price volatility inherent in the UK system?

It’s a shame that Australia has inadvertently adopted the worst aspects of the UK housing market, namely: the UK-style planning system, complete with similar vertical fiscal imbalances with respect to federal, state and local taxation revenues; a deregulated rental market offering insecure tenure; and a deregulated mortgage market that provides low deposit finance at generous multiples of income.

Maybe, just maybe, the current problem the UK’s facing (which I suspect will involve more real housing price falls, quite possibly also nominal), would be a trigger to change to something more sensible like this.

“numerous articles advocating the Texan approach to land-use planning”

Linky?

You could not run England like Germany without very different consequences. A better comparison would be Holland, because of population density, limited areas of countryside which are strongly felt to be a public good which private development should not be allowed to damage, and a rising population.

The German policy in England would cover the whole place, countryside and all, in houses and concrete, and that, they do not want.

There are rather large parts of Germany not covered by houses or concrete.

As a matter of fact, Germay has more than three times as much forest coverage (32%) as the UK (10%), and the comparison would be much much more starker if you took only former West Germany vs. England (if you wanted to compare two developed countries).

Personally, I feel that there’s quite a lot of land in say East Anglia on which development would not destroy any aesthetical value of the countryside.

Of course, the large difference is that Germany also has the infrastructure to support reasonable commute better than UK. I can’t but laugh every time at King Cross when I pass the plaque saying (approx). “The first high speed rail in the UK started operating from this station in 2007”. Yeah right, catching up with the rest of the world…

Yes, but Germany is a much bigger and less densely populated country. This is why the German policy works, but it would have quite different effects if put into effect in England.

The result in England would be the vanishing of the public good of the countryside. This is the price you would pay for that particular mechanism for lowering house prices.

Most English people would probably decline to pay that price, and there is another means to the same end, namely, urban redevelopment.

Er.. No? Depends on what you’re comparing – former West Germany or the current Germany?

Area of West Germany is comparable with Britain (248k km2 vs 242k km2). Population density in WG was about the same in 1990 as is in the UK in 2010. Now factor the 3x higher wood coverage, and you got considerable less space to build than in the UK.

And before you say about comparing apples and oranges, there was/is a significant exodus from former East Germany (so that large parts of it have now pd 2k.

And I’d point out that RW also has rather large forest coverage too. Adjusted for forest coverage, RW is about comparable with Greater London + Home counties area and population-wise.

The dutch housing market is quite comparable (in badness) to the English one. We have rent control and price controls on social housing, but the private market has been totally ruined by the price increases of the last decade or more. Land use is similarly organized (building new housing is quite hard), and there has been a housing shortage (especially in the affordable rentals section) for years.

The same thing would happen in Holland as would happen in England, if you allowed unlimited building. In a couple decades it would be an entirely urban environment. After all, its not much bigger than LA. Its entirely possible.

But, people seem to be prepared to limit private ownership of property and limit property rights in what you can build where, for the sake of a public good, the ability to ride bikes along the Vecht at the weekend, or go for walks followe by pancakes in the Laage Vuursche.

They probably do know what they want.

Yves – You allude to it in the last paragraph, but I’d be interested to hear more about the housing situation in Australia. After moving to Australia from the States in 2010, I was surprised to see that the housing market is not too dissimilar from what the States was like pre-2008: recent large increases in prices with average cost to income ratios well in excess of 4.0. Credits not cheap here. But are Australian banks pushing mortgages? Is there a hold on supply? Or has the booming economy created such a large increase in demand?

Click the Macrobusiness link,they have reams of excellent Australian housing data, research and opinion.

I’ll comment further on the thread, but Australia – like US – bases mortgages on pretty much the price of money (interest rates) and has a big ‘home ownership culture’.

The pressures for ‘affordable housing’ in a political culture that worships home ownership and sees all levels of government as somehow diminishing individual initiative is that you get subdivisions built on floodplains and other lands that are not well suited to development.

In other words, you meet the ‘affordable housing’ goals by screwing your environment, which means you then have floods that become more and more destructive over years and decades. It’s lunacy.

I live in the Puget Sound region of Washington state and the cheapest lands are primarily agricultural land bought up cheaply, then converted to subdivisions via rezones (which requires a lot of political campaign contributions to elect the sort of weenies who will do the housing developers’ bidding and ram through all the subdivision rezone requests). These lands are always in flood zones.

A similar thing occurred in the Brisbane, Australia region the past 14 years or so, and how on earth the Brisbane and regional governments allowed building permits in their flood zones is not clear to me. But talking with friends during the Brisbane floods of 2011, while waiting for high tide in Moreton Bay, their predictions of which subdivisions in the Brisbane area would be flooded were just about spot-on.

For flood photos to refresh your memory, see here: http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/gallery-e6frer9f-1225983022068?page=1

Until we all do a better job of mixing hydrology, soils chemistry, agronomy, and also climate science into our ‘affordable housing’ criteria and goals, what I suspect we’ll end up with is an exponentially increasing mess.

Already, the development in Puget Sound has severely impacted salmon spawning and salmon runs — hence, the rising prices of salmon, which is never calculated into any mortgage rates, now is it?

Similar dynamics throughout Queensland, which has traditionally had fabulous seafood and at least along the coast very good agricultural productivity.

So we have not yet mixed ‘affordable housing’ with sensible environmental procedures and processes.

For instance, as far as I’m aware even in my ‘eco conscious’ part of the US we still do not have a mortgage rate that gives a lower interest if your house is truly ‘Built Green’, or built with environmental stewardship in mind. That kind of construction happens in high-end construction, including businesses, but presently does not receive a long term interest rate that reflects that it IS **more affordable over long time horizons** to build ‘green’ rather than simply ‘build fast and stupid’, which is what we’ve been doing for far too long.

Other areas of Australia, like the US, also exhibit sprawl patterns that are environmentally catastrophic over time. Yet so far, these factors are not at all aligned with ‘affordable housing’ conversations. (Except at INET, see William Rees’ work.)

Yet in the US the places that are the most UK-like, the Northeast say, are much less affected than the most German-like, the sand states.

Dear Yves,

I liked your analysis very much. However you forgot one important point: taxes.

There are almost no tax incentives for owning real estate.

There are some incentives for renting out, but due to the tenant rights renting out is not a very profitable startegy as well.

Many people who invest in real estate actually rent their own place and own real estate which they rent out to realise some tax deductions.

Some people I know do this on a bilateral basis, so one party buys and rents out to the other and vice versa.

there was a brief period of time after the unification when there were huge tax breaks for real estate in the former GDR. The result was a temporary boom and a long bust with many people having overpaid for flats and houses in the east. It hink this also prevented a real estate in the 2000s

memyselfandi

I would attribute the differences mainly to monetary policy. The more people who are mortgaged to full capacity, the more monetary policy makers are under pressure to go easy on them, so the more borrowing to buy pays, so the more people do it, and so on. And of course, the more fiercely owners try to protect their housing wealth from new development. It is cultural moral hazard. In Germany, the Bundesbank and the ECB have been a bit tougher, so their housing market has avoided bubbles. It seems to me that the number of TV property programmes and newspaper property supplements in the UK is a sign of this – I would be interested to know whether such things exist in Germany and other countries.

I had high hopes that BoE independence might break this cycle in the UK, but as you see with the present situation, when the constraint became binding, with a few honourable exceptions, the monetary policy committee backed down regardless of the inflation target. My experience of the engrained nature and toxicity of this cultural moral hazard is, by the way, why I favour a tougher line on debtors from US mortgage borrowers to Greece.

“While the majority of rental dwellings in Germany are private, rents are regulated and prices are prevented from increasing sharply. Tenants also have security of tenure as long as they pay the rent and behave well, except on the rare occassion when a member of the landlord’s family needs the accomodation or when the building is going to be replaced.”

The UK rental system used to be a lot more like this before Thatcher’s “reforms” in the late 1980s. Under the old Rent Acts, tenants had security of tenure and price controls.

The outcome of the economic revolution inspired by the Chicago Boys has been the same everywhere it has been implemented, and especially in its purest Reaganite and Thatcheriete manifestations. The first examples of this to materialize were in Latin America. (See Greg Grandin’s Empire’s Workshop for a thorough explication of this, a short synopsis of which can be found here.)

The neoliberal’s wet dream has come true beyond the Chicago Boys wildest dreams. After Latin America, it went global. The neoliberal wet dream was not to increase new assets, or production, but to extract more rents from existing assets.

Carlos Fuentes made this very clear in A New Time for Mexico:

Mexico needed—and did not get—policies encouraging investment in activities that would further employment, wages, growth, and savings. Instead, the Salinas reforms provoked a flood of speculative, unregulated capital that did not go into productive areas. Like flight capital in any other emerging market, it stayed in Mexico as long as it was profitable to stay and fled as soon as dark clouds started accumulating in the sky…

Never has Mexico received as much foreign investment as it did during the Salinas years: almost $59 billion between January 1989 and September 1994, but of that enormous sum, almost 85 percent was speculative flight capital.

[…]

The economy became hostage to foreign investment in order to maintain the peso’s parity and pay the current-account deficit. But foreign investment was concentrated mainly in stocks, bonds, and other short-term instruments: in the volatile and transitory paper economy. Only 15 percent of foreign investment went into the real economy, into creation of factories, increased employment, and increased production. The country was threatened with an acute case of schizophrenia. A minority centered their lives on the New York Stock Exchange, and a majority on the price of beans. One economy was all gilded wrapping paper, the other all huts and untilled land. The former was the minority’s, the latter the majority’s.

If we take a longer historical perspective, however, the revolution inspired by the Chicago Boys was actually a counter-revolution. Its purpose was to reverse the reforms that came out of the New Deal revolution, a counter-revolution to carry us back to the Roaring Twenties.

The PBS special The Crash of 1929 does a great job of recounting the 1920s era. It was a time when production was spiraling downwards at the same time rents and prices were spiraling upwards, a Ponzi scheme if there ever was one.

For more on this there’s Amitai Etzioni’s chapter “Political Power and Intra-Market Structures” from his book The Moral Dimension: Toward a New Economcs:

The economic literature is replete with references to distortions the government causes in the market. Comparable attention should be paid to manipulation of the government by participants in the market…

[….]

In the neoclassical paradigm there is no room for the concept of power. Says Stigler (1968, P. 181): “The essence of perfect competition is…the utter dispersion of power.” He adds that power is “annihilated…just as a gallon of water is effectively annihilated if it is spread over a thousand acres.”

[….]

The strategies and means typically studied tend to be intra-economic: they are employed by economic actors using economic means to economic ends.

[….]

In contrast, we shall see that the government provides a commonly used and highly effective way of capturing and holding on to market shares, of curbing entry of competitors, and an avenue for collusion…

To the extent that the use of the government by powerful economic actors is ignored, the [neoclassical] analysis also disregards one of the most effective ways of gaining so-called excessive profits, not by setting prices above marginal costs, but by charging market prices and using the government to acquire one or more input factors at costs substantially below those that competitors must pay. These include gaining capital at below the market interest rates…and exemptions from laws or regulations such as those concerning the minimum wage or immigration, outright subsidies;…purchase of government assets at fire-sale prices…

[….]

In short, economic actors can, by the use of political means, achieve various effects often attributed to concentration of economic power.

The theorem just stated is in opposition to the Marxist notion that political power merely or largely reflects economic power. While it is true that if an actor commands economic power it might be converted into interventionist power, economic power is not a prerequisite for interventionist power, and interventionist power is often the source of economic power. While many actors command both kinds of power, there is no necessary correlation between the two. (All emphasis above is Etzioni’s)

You presume a pull effect, but I would posit that before (or simultaneously with) the pull there was also a push, in part because there were few other places to park your savings that offered (bubble) RoI, and because the government wanted to make the banks grow (the financial sector gets enormous amount of policy ‘help’ from the UK govt to become as obscene as possible, and the same thing to a lesser extent has been happening in NL) they also started to create incentives and possibilities for the banks (allowing people to take out 100% mortgages, increasing the leverage on yearly income, counting the income of the partner).

This is very interesting, but I’m wondering about the assumed relationship between affordability and liberal supply. During the bubble here in the US, we had huge excess inventory build-up AND a tremendous run-up in pricing. Perhaps this is partially the result of the difference in degrees of federalization in regard to land use between the US and Germany and the UK. At any rate, this analysis is a nice beginning but it seems to me that there needs to be much more thought given to these differences and the causes of them.

Financing is the probable difference. The article points out that Germany maintained strict standards on loan-to-value ratios and mortgage borrowers’ incomes.

In Las Vegas, by contrast, no-doc, teaser-rate mortgages at 100% of value provided ‘free money’ for speculators to buy houses (one lady ended up owning 19 houses as investments), while securitization provided cheap no-recourse financing to developers to build even more new subdivisions in the desert.

In the long run, excess supply and rising prices cannot coexist. But thanks to Goofball Greenspan’s 1 percent Fed Funds rate, and total nonfeasance by bank regulators and the braindead SEC, for a few magical years they did.

In terms of national psyches, Germans (owing to the searing experience of Weimar) fear inflation, while Americanos (owing to the searing experience of early 1930s collapse) fear deflation. Germany will staunchly resist housing bubbles, while the US tendency will be to indulge in insane, reckless flimflammery such as quantitative easing to keep prices rising at all costs.

A big driver of this involves home builders and developers.

(The developers buy the land, rezone it, get power and sewer and water to it. They are sometimes also builders, but generally they move on and do the same thing elsewhere, then sell finished lots to builders.)

Unless you are high-end and/or have solid technical and engineering skills, you can make good money as a subdivision builder creating McMansions, because that is your most profitable ‘product’. Or was.

So the builders were incentivized to build McMansions.

The developers were incentivized to demolish the environment to build lots for McMansions.

The genuine affordable housing was left to non-profits, or government entities.

The result is expensive disaster: too many overbuilt homes on big, sprawling asphalt-covered cul-de-sac bulbs that are incredibly expensive in terms of transportation and energy use.

I have literally been in meetings where big subdivision developers wailed and whined because they ‘couldn’t afford’ to build affordable housing. Translation: “we’re in this to cream as much profit as we can, as fast as we can and if 70% of the population ends up crammed into shitty apartment, that’s not our problem.”

Until these guys have better incentives, we’ll continue to have one nutty cycle after another.

And every one of those jerks will blame the government, blame Obama, blame Bernanke, blame The Fed, blame whoever they can blame, because they don’t have the cajones to look in the mirror and ask how they can be part of the solution.

The ‘solution makers’ are the people busting their asses to figure out how to create more sustainable building models. It’s a big problem, but also a *huge* opportunity.

Nothin’ but opportunity; if you can figure it out, the world’s probably going to be your oyster.

The UK has three at least housing markets: (1) London (2) Some other smallish islands of high cost e.g. Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, … (3) Elsewhere.

But London is a large proportion of the total – far more than, say, New York vs the rest of the USA. And it’s densely populated, buzzing with activity, and a favoured property investment location for citizens of countries with shaky legal systems or currencies: compared to it, Berlin – for example – is a one horse dorp. You need to allow for these differences.

Among the things that need attention in the UK are, I suggest (i) the English system of house buying, which is slow and uncertain – it needs to be improved along Scottish lines (ii) the English system for owning flats, which is risible – it needs to be improved along Scottish or Australian lines (iii) improvement in the disgraceful state of English law on the subject of squatting (iv) imposition of Capital Gains Tax on profits on the sale of Principal Residences (i.e. owner-occupied housing) and/or the reintroduction of Schedule A income tax i.e. a tax on the imputed rent on owner-occupied housing (v) abolition of subsidised rents and permanent and inheritable tenancies on “social housing”, which are a corrupt extravagance made redundant by the existence of “housing benefit” (v) an increase in the number of types of lease available to landlord and tenant.

That lot would be a good start, irrespective of any desire to emulate Germany, Japan, or wherever. Of course, one might reasonably wish to relieve the pain of contemplating policy errors of the last decade and a half by jailing Gordon Brown and the Goveror of the Bank of England, and hanging Tony Blair, but that’s probably only a pipe-dream, alas.

dearieme;

I don’t think that James I foresaw the results of the ‘Long Parliament’ either. One thing no one has bought up yet is the cost per square foot diferences between the ‘markets’ used for comparison. I know that my relatives back home in England think I’m pulling their leg when I tell them how much space we got for the price here in the CSA.

At some point, every country runs out of undeveloped land. From an urban planning and architectural perspective, ‘artificial’ constraints that contain urban sprawl, as practiced in the UK, can only be commended. For the UK, it would be even more useful if the countryside were actually fully accessible to the public and equipped with the corresponding infrastructure. From what I can tell, most of the countryside in the UK is still stuck in feudal times. Pretty, but useless to all but its owners.

No, the English countryside is not stuck in feudal times, its full of bed and breakfast establishments and in summer, its full of visitors walking and cycling and boating. Its a real public good.

The German real estate market is currently booming. Der Spiegel calls the bubble and wonders when it is going to burst:

http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/unternehmen/0,1518,741694,00.html

Why it is happening now, after the rest of the world has had its share of real estate madness, is up for debate. Just wanted to point out that things can go wrong in Germany as well as the UK.

Notice that top six spots on the Homeownership Rate chart are comprised of the “PIIGS” countries plus Belgium…

Any thoughts?

My hope is that some of the huge amount of space coming on the market, thanks to former Mayor Ken Livingstone’s love of tall buildings, is converted to residential, and supply tanks prices.

“The result is that people rent not because they can’t afford to own (which means they are financially less stable) but because they prefer not to (for instance, they prefer the flexibility, or decided to put their money in a second home or in investments). And tenants who have property rights (as in the landlord cannot deny them a lease renewal if they are current on their rent) not only take better care of their unit, but I’ve seen them actually make meaningful investments in them (this happens a lot in my building).”

I lived in Brooklyn for 11 years, and I have to say, my experience was somewhat different. Most of the people I knew were renters because they could not afford to buy, period. In my neighborhood, buying was a much more expensive option (admittedly, this period covered much of the “bubble” years). I did know a few people with “weekend” homes outside the city; most of them did own their own condos or coops. I lived in a rent-stabilized apartment for a while, and maintenance was very poor; “investment” was only made to justify rent increases. When my building was sold, the new landlord was even worse, even with fewer stabilized apartments. Eventually we were just squeezed out.

We Have lived in the same rent controlled duplex for twelve years. Love the neighborhood and landlord. We’ve made many improvements including refinishing the wood floors, adding a dishwasher, garbage disposal, replaced the garage door, replaced light fixtures, etc. We have a small garden out back and have kept the place in fresh paint. To buy a similarly sized place would cost three times as much a month plus property tax….so why bother? We’re in Los Angeles though. The only way we’d move would be if our work required relocation.

This good article leaves out an important feature in the German system: Its rental co-ops. A large number of Germans belong to these co-ops, which hold down rents to reflect actual operating costs much as were done for years in New York, where the right to move into a co-op in my old Manhattan neighborhood was only $3,000. Labor unions created many co-ops in New York, and also in Germany. Public authorities created others.

The availability of such housing saved Germans from being panicked into buying.

Also, construction prices are not monopolized there. I have seen wonderful custom-made windows installed for $3,000 — half the cost of inferior pre-fab windows here in New York.

The other points are well taken: no 100% mortgages, no liars’ loans, and little absentee buying to make a profit. Especially in East Germany, having property was a problem, not a solution. The old Communist state would tell you whom you had to share your house with, and you were obliged to take care of it. (DYI stores are more frequent in Germany, I think, than here.) So there is a cultural tradition that is almost a fear of home ownership in the East.

Michael Hudson

I should add a point re England.

In Central London — where rents and housing prices are so exorbitant — a reported 80% (NOT a typo) of property is owned WITHOUT MORTGAGE. Mainly by foreigners, and much of it flight capital in effect.

People who actually have to work for a iiving in London are obliged to live WAY outside the city. When companies advertise, they often say, “Salary includes season ticket.” This is NOT a ticket to a soccer club. It is a train ticket to get to where you have to live, as foreigners (I plead guilty) have bought up the central London property.

Also, re capital gains, if you buy through a partnership in one of the crazy offshore British isles, you do NOT have to pay a capital gains tax. this, to encourate “foreign investment in Britain.” So most British absentee landlords appear as “offshore.”

The moral is that the real estate market is not like any other market, either in Britain or elsewhere.

“….as foreigners (I plead guilty) have bought up the central London property”

Well, with your attitude towards those who hold their wealth in debt (I assume you are that Michael Hudson), I can only hope that you are dispossessed by squatters as soon as possible.

Hi Yves,

Seems you glossed over differenced in Planning between UK and Germany. I see Central Planning and Specific Regulations as being aspects of the same process.

I find it hard to believe that Germany doesn’t create specific regulations or requirements from a set of more general policies (a plan) whose goal is to protect resources as farmlands, Forests, Water Resources and wetlands, and to generally locate heavy industrial operations so as not to degrade residential areas (as examples). I suspect that the Germans do have a central plan. It seems the difference between UK and German Housing may not be in planning, but in having clear rules and administering them efficiently.

I can see how the UK (and US) bias towards so-called “home ownership” including financing standards and renter protection, creates a different outcome than the German approach. I suspect UK and US processes (at least in California) are similarly unclear, and uncertain, and are politically administered.

You had me at ‘politically administered’.

In the US though, we still have the profiteers intent on keeping people’s basic needs out of reach. This rarely comes up on this blog, but bandits will price people out of water if they are allowed to do it.

As an example of a delusional cheerleader working on behalf of Bankster looting, here’s Kay Hagen, BOA employee:

“The strict, inflexible restrictions proposed by banking regulators could put home ownership out of reach for many creditworthy American families.”

Re: “I’m intrigued to see this article highlight an issue that I have stressed as a New York City resident, where tenants have much stronger rights than almost anywhere in the US: that strong tenant protections actually help landlords.”

Pul-leeze! Do you think that you know what’s good for landlords better than the landlords do? Do you think that rent-controlled and rent-stabilized apartments help landlords?

There are wealthy people in NYC with huge apartments in prime locations that pay what a one-bedroom apartment would cost on the free market. Renters of smaller apartments often live elsewhere and keep the Manhattan apartment as a pied a terre. The phrase “rent-controlled pied a terre nyc” input to Google comes back with 5800 hits; it’s not a small issue.

By reducing the supply of free market-priced rentals, the rents of those apartments are artificially high. People who pay market rents are effectively forced to subsidized the rents of people in rent-controlled apartments.

Another problem with “renters-rights” in New York City is that is takes at least a year to evict a deadbeat or otherwise undesirable tenant.

I live in Manhattan, I’m not a landlord, I rent and I’ve never heard anyone suggest that the “tenant-rights” in New

City benefit landlords.

My landlord, who owns a huge office building (on Park just north of Grand Central Terminal) and 7 apartment buildings, knows vacancies are costly and is pretty accommodating to tenants that pay on time. When I went overseas, they approved my application to sublease pronto, twice; they could have easily dragged their feet so I’d lose my subtenant. Similarly, even though I had no legal right to sublease for a third year, they agreed to do that.

So they clearly are not of your view on this matter and they are big time landlords.

Compare the German Housing Market to the UK Housing Market ….. what a shambles the UK is! Here’s why:

1) Snobbery among the fake middle classes, most of whom are actually POOR

2) MASSIVELY overpriced housing, thanks to greed at every level of society …. banks, home “owners”, media types, estate agents, et al

3) Rental prices are tied to house prices. Overpriced houses mean that the “But To Let” brigade pass their costs onto their tenants.

I applaud Germany for using sense to rule their market. Britain used greed, social engineering via the media, and snobbery, to create a market in terminal decline.

The UK is the most indebted country in the World (per head). Much of the debt is thanks to the nation’s obsession with house prices, and GREED.

A couple comments about Germany and home ownership. 1st, parents can send their children to any school in the city where they live. You don’t have to buy a home in the right neighborhood in order to get your kids into the right school. 2nd, German homes are expensively built (built to last) compared to US homes. Almost all have basements, and the walls are concrete or concrete block. Wood-frame houses are the minority. 3rd, often in the US one builder will build every home in a subdivision. This probably results in some efficiencies (lower costs), even if it unfortunately causes all the homes to look alike. Here when a new subdivision opens, people individually contract with different companies to have their homes built. As discussed in the article, the houses must be build to conform with local guidelines (maximum height for instance), but within those guidelines, the owners can build as they like.

Many US houses are constructed with the cheapest possible materials.

It is a scandal.

It is also a sign of how stupid the banks are.

How allowing crap construction in a woodland wetland – so the house is going to mold within six years – to be passed off as ‘affordable housing’ is a mystery.

The idiotic bankers who lent money for 30 years on houses that will mold in 5 years deserve a whole new level of hell. And the weenie electeds who enabled it deserve to share it with them.

‘Planning’ can be cost effective, and I would argue that smart planning and good energy use creates wealth.

By lending on poor properties, the banks destroy wealth and the environment at the same time.

If planning controls in the UK caused the house price bubble, why was the bubble even more extreme in Ireland, where there were hardly any restrictions on building houses in the countryside? Not only is Ireland now insolvent, many of its towns and much of the countryside is now ruined by sprawl. At least in the UK we still have walkable neighbourhoods. The problem in most UK cities is that demand from buy-to-let investors led developers of brownfield sites to build too many small flats, leaving a shortage of family houses.

Sprawl and bank insolvency are deeply connected.

”

taxation revenues; a deregulated rental market offering insecure tenure; and a deregulated mortgage market that provides low deposit finance at generous multiples of income.

”

~~Yves~

You have grazed the surface with your silver bullet. Should we probe more deeply with your silver probe, more deeply into the most despicable detail of devils, *tax*?

Median price of new home is now $220,600.00. Weighing on that median priced home there are visible and hidden taxes collectively weighing in at $90,000.00. Is that tax 40% of the construction money? Depends how quickly you pay the bill. If you borrow the funds to pay the tax, you got to add in interest on the borrowed-for-tax-$$. Will the mark-up for tax( the cost-over-run for tax )cause a drag on construction industry volume? As home construction volume drops does economy of scale drop? Ah! Another hidden mark-up == lost economy of scale.

Tell me something! How much of the home tax money finds its way back into Freddie/Fanny subsidies or/& other “home ownership promotions from fearless leaders in government”? 2%? 3% Who made off with the other part? Overhead? Overhead of taxation-administrative-costs? Kickbacks? Political donations? The shadow knows! The shadow inventory.

Will lack of housing regulations screw lot of people out of home that is not in good neighbourhood? Not free of rats? Cockroaches? Would less regulations allow more efficiency? Efficiency which would bring home prices down until everyone could live inside safe neighbourhood?

“You not suppose to lower home price”, Citizen. Then we couldn’t get as much tax from the transaction. Worse yet, undesirables could then afford homes in our neighbourhood.

Where does all that tax and regulation money go?

To the rats

?

Very nice article Yves. Thank you. I will forward this to my finance friends.

I have a one quibble though. I beleive the article should have had increased emphasis on the credit policies

of the nation. I believe the effect of credit availabilty and credit polices is the major determining factor in the asset price of real- estate. When housing prices exceed income by various multiples, it is the prevailing credit polices that determine the ‘effective demand” in the housing market and resulting transaction prices and the resulting debt accumulation. No unsustainable bubble can occur without increasingly lax credit

policies.

Any thoughts?

During the Weimar inflation in Germany in the 1920’s house prices did not increase. Rent control was so strict that landlords were destroyed as their rental income morphed into a pittance insufficient to keep the property properly maintained. It may be that wild west real estate markets like the UK and the US serve as a sponge for excessive credit creation and somehow protect their economies from hyperinflation. It would be interesting to see actual house prices in Germany vs the UK. My impression from speaking with Germans I meet overseas is that their house prices are not cheap, but in fact are quite expensive.

«Unlike Germany, the UK housing market is essentially a bubble factory.»

The article and much of the comments are completely a waste of time, because the difference between USA, UK, Eire, Australia, etc. and countries like Germany is not based on technicalities, it is entirely political.

A group of countries have had huge increases in house prices because some conservative interest groups supported by many middle aged voters decided to create huge capital gains bubbles to encourage property ownership, as that gives a strong incentive to vote conservative, and to delude the vast mass of sucker baby boomers that they could rely on housing capital gains for their pensions, and pensions were only for parasites. The same things happened in the same countries for other assets. Capital gains bubbles were engineered in all of them by deliberate political choice, fueled by colossal leverage bubbles.

Housing and other capital gains bubbles have happened in those countries that wanted them. Germany and other countries instead decided to base growth on production and exports.

My impression is that the only country where a huge housing bubble was not a political goal is China, where it was a side effect of other policies, and that Chinese rulers are very afraid of their housing bubble.

England has the worst of the worst of the last 2 social orders operating simultaneously. First, it is a backward feudal monarchy run by a Queen and her family which continues to own much of the land of London and in conjunction with other feudal counterparts, including other noble families and the church of england own most if not all of England. Second, it has the worst of the so called market system.

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/who-owns-britain-biggest-landowners-agree-to-reveal-scale-of-holdings-443956.html

Astoundingly, the right wing media of the US along with the BBC, continues to fawn over all things royal and british. The only worth while exception to this nauseating display of fealty is the rock and roll exported from the Liverpool and other working class areas of the commoners.

If you look into the matter of the land in England in the above article, you will find that not only is much land not even a matter of public record, the aristocracy is continually scheming to put even more acreage beyond the reach of any but the HM Government in various nature or heritage trusts. Prince charles is one of the leading con artists of the world with his prissy back to nature neo-hippie human scale self contained organic gardening walkable village. What is really going on, is that even more land is put into bucolic splendor quarantine, beyond the reach of development in the near future, while people are crowded into the ridiculously dense UK housing market.

http://www.who-owns-britain.com/

While I don’t know enough to agree or disagree with your broad comparison between the UK and Germany, I don’t see why your first heading, “Housing Supply” should offer a virtual paean to the unlimited supply of housing, aka, build where you want.

Living in Portland, Oregon, I’m quite happy with an urban growth boundary. Developers are not, and they often use affordability as an argument for suburban development. And while growth limitation may seem to privilege those of us who already own houses, in my observation it also encourages the use of vacant land within the boundary, the transformation of old industrial land into housing, and the rehabilitation of neighborhoods. Living spaces are smaller. Portland had its housing bubble, but the largest bubbles in the U.S. occurred in places where suburbanization was rampant.

Urban transformations create new areas of economic segregation on the periphery. Portland tries, but does not do enough, to build new “affordable” housing. In general (I’m also a landlord) I favor more public control over housing. That’s why limiting development and encouraging density –urban planning — ought not to be seen primarily as harmful limitation of “housing supply.” The other aspects of the German system you describe make perfect sense.

A small further point. Any system of rent control needs to be very carefully targeted. I think public ownership of affordable housing (tax based) is preferable. In my early experiences in NYC and Boston, rent control sometimes produced a sub-class of entitled tenants whose capitalist instincts (especially if sub-leasing) fully matched those of property titleholders.

One point that I meant to make on this thread: it sounds as if the German law places more legitimacy on land use plans, as well as the local level of decision-making. The incentives are aligned with the policies.

In my US state, the ‘urban growth area boundaries have produced volumes of pay for land use attorneys, and mostly public wasted expense, defeated hopes, and sullen resignation after the attorneys win and the weenie electeds cave.

This occurs through a process by which campaigns are financed by private (mostly building and home development) interests.

Then, as per the type of process that Prof William Black has pointed to with respect to the corruption of judges by requiring them to run for office and require campaign funds, the ‘land use plans and policies’ end up before judges. Many of those judges were elected with developer money and influence.

It is then no wonder that in regions like mine, where the legislature enacted Growth Management laws and specifically stated that ‘plans are laws’, the builders took that to court and the judge(s) ruled that plans are NOT laws.

So one factor not yet mentioned in this thread is what we might call the “Prof William Black warned us about politicizing judgeships’ factor. In other words, judges who rely on campaign funds for election get a lot of their money from home builders and mortgage bankers and realtors.

When a legal case comes before them, challenging whether a Land Use Plan does carry the force of law, or whether it is just a ‘set of goals, a desire’ then the judge is almost certain to side with the builders.

When judges do that, we’re off the UK end of the spectrum and headed for Bubbleville. So designating the legal status of land use plans, and keeping the land use process as non-political as possible is a key factor in taking the steam out of the bubble dynamic that surrounds the ‘affordable housing’ mantra.

Interestingly, In Spain building planning is also a funtion of the municipalities although here, the incentives to promote building are even stronger. Instead of grants, municipalities act as an interested party and the fees they gather for building permits have been the most important municipal revenues during the bubble. The higher the price of housing, the larger fees collected for building permits or “licencias”. Those skyrocketing “licencias” boosted a corruption boom at the municipal level.

This is one of the reasons that explain overinvestment in residential building in Spain. At least centralisation would had reduced this incentive.

Also, it is interesting to note that despite the residential overconstruction in Spain (number of houses buildt in Spain in the good old 2005-2006 years were a record for europe) prices went up sharply. Only Ireland house prices showed higher increases).

Of course, that was part of the bubble: house flippers are to be blamed since they “signalled” many residential units under construction as “sold”.

Thus, beware those incentives to building, and at least try to ensure that they are independent of house prices.

Sigh.

As always, it’s not quite that simple. I’ve been living in Germany for over 20 years now and while nothing that Yves said is really wrong, it’s simply not that simple.

There are strong limits on building in Germany (rezoning is a serious nightmare for anyone trying to turn agricultural land, for instance, into residential land), largely because there are in fact vested interests in keeping housing costs for single-family dwellings as high as the market will bear. While this benefits both the local government (since assessed values for tax purposes are high) and builders (since they basically control the supply and ensure that building is itself very expensive), the losers are consumers, many of whom start saving for a down payment when they are born (a “Bausparvertrag”, where you pay in a set fee and 20 years later get more money back, sort of like a savings bond, is a very popular birth and christening gift amongst German middle class families) and sacrifice their entire lives to getting a piece of land and building on it, giving up vacations and investing bonuses in order to afford their own place.

German construction codes are basically designed for a 150 year build-to-tear down cycle, with major renovations every 50 years, while US codes, for instance, are designed largely for a 75 or even 50 year cycle: houses built 100 years ago reflect very, very different consumer needs and design abilities. While you end up in Germany with massively solid (and stolid) housing, this is massive over-engineering, since houses built so massively cannot be easily changed and modified into more modern designs: a significant portion of the money you spend on a house, based on this housing life-cycle, is money that only benefits follow-on owners. While this improves, to a certain degree, re-sale prices, a significant portion of existing housing is torn down after resale because the design of the place is, bluntly abysmal: many older houses have multiple very small bedrooms, for instance, for when families had 4-6 kids, but given the average family size in Germany, having 1-2 much larger bedrooms makes more sense: unfortunately, knocking out walls is impossible because of the fact that most walls are load-bearing, rather than drywall, forcing you to tear the place down and rebuild in order to have the floor plans you want. The older the house, the more likely it is that you’ll want to do this.

There is also the fact that rental prices are heavily influenced by large numbers of government-owned housing. There were put up largely for government employees and the military in order to provide subsidized housing so that German government employees and soldiers could be paid significantly less; given that these prices are included in what is called “Mietspiegel” or the official average rent prices. German law does control how much and how fast rents can increase, which is moderate and orderly, with real jumps only occurring when a tenant leaves a property. Generally speaking, rents may only increase at around 10% a year until they reach the Mietspiegel, at which point they may increase not more than 20% over a three-year period. That’s a built-in brake to rapidly increasing rental costs.

Most rental unit owners are loath to lose good tenants, given the risk of rental nomadism (moving from place to place while not paying rent, staying one step ahead of the lawsuits: rental nomads are the bane of the unit-owners existence, since they can usually milk you of 2-3 years’ worth of rent before you can actually get them out of your place, which is then usually in need of major renovations) and the general aggravation of having your cash flow interrupted when you are still paying off your mortgage. As a result, as long as the cash flow works, you can generally expect rental prices increasing only according to the rate of inflation at worst. Given the large percentage of renters, it’s more of a renter’s market than a landlord’s market, as it is easier to move than to sue your landlord for poor maintenance and the like (and people really do that as well).

There’s also little social stigma for renting, rather than owning, unless you are in a very high income cohort (and even then it’s more a matter of curiosity, rather than stigma). While for some ownership remains a mantra of materialistic consumerism, us post-materialists prefer to rent and enjoy avoiding both debt and interest rates…

I’d go for rent control if it was structured to:

1) Discourage low-wage labor to stick around after low-wage jobs leave. This is a marvelous prescription for property&violent crime-based economies.

2) Housing subsidies are allocated according to need, rather than the ability to stay in one place.

Really, rent control at its finest would merely discourage rents to oscillate with land prices. I lived in San Francisco during the dot-com times, and universal rental hysteresis would have been a good thing.