Yves here. I thought this discussion of Baumol’s disease would be of interest to NC readers because the issues are relevant for advanced economies generally, not just Australia.

By Cameron Murray, aka Rumplestatskin, a professional economist with a background in property development, environmental economics research and economic regulation. Cross posted from MacroBusiness

Why does the wage of a musician in a string quartet rise over time at roughly the same pace as wages in other areas of the economy, despite the lack of productivity gains in the performance of music?

William J Baumol solved this riddle in the 1960s. His insight, known as Baumol’s cost disease, is fundamental to understanding changes in the economy over time. If we are going to debate the shift towards a service economy, productivity, unemployment, health and education costs and government intervention in markets, we need to fully appreciate his insight. Unfortunately you won’t find his ideas in many introductory economics textbooks.

Baumol’s disease can be explained simply. Only some areas of production will see strong improvements in labour productivity, typically through the substitution of capital for labour (such as in manufacturing and agriculture). Workers in these industries use their bargaining power to capture part of the increased profitability arising from productivity gains in their wages.

As a wage differential between these newly productive jobs and other existing jobs emerges, workers are faced with a choice of seeking employment in the high paying productive sectors or the lower paying unproductive sectors. Employers in the unproductive sectors still need workers and the wages need to remain competitive with the productive sectors to attract them. Bargaining between workers and businesses in each sector (including government sectors) equalises wages over time. Thus productivity growth in just one area of production is shared amongst workers across the economy.

This means the cost of labour intensive services with low productivity growth will increase relative to other goods and services in the economy over time. In addition, the amount of labour employed will shift towards service sectors with low productivity growth. Ever wondered why all developed countries seem to have relatively large service sectors? This is part of the story (the other part is displacement of tradable industries to cheaper locations).

Baumol’s original article and subsequent works highlighted the importance of his cost disease to the provision of fundamental health and education services. The crux of his argument follows from key the finding that increases in the cost of providing these fundamental services in the economy are unavoidable (the disease has no cure). Therefore tough decisions need to be made about whether these services are provided through an expansion of government provision, and the increasing share of the economy the government will necessarily have to take, or whether these social services can be provided through private enterprise, and the associated problems of gaming and moral hazard this may entail.

We can expand on these points to explore the relevance of Baumol’s observation to contemporary political debates.

One key area of public debate is the decline in manufacturing and the apparent loss of productive industries where workers ‘actually make something’. While clearly one fundamental driver of this change is the shift of manufacturing offshore, another key reason is that the economy simply needs fewer workers in these areas because each worker is becoming more productive.

The recurring debate about the rise in public healthcare costs also needs to catch Baumol’s disease. To make any progress in the provision of health care all sides of politics need to acknowledge that the cost of health care MUST rise over time relative to other goods and services if the economy is experiencing any form of productivity growth (noting the current temporary decline in productivity growth in Australia). Budgeting for this cost growth in health care over time is absolutely necessary, particularly in light of the demographic shifts occurring.

Education is the other area where governments need to acknowledge that cost escalation is unavoidable. While I don’t want to give governments an excuse to waste money operating schools inefficiently, but there are limits to productivity growth in this area. Teachers will still teach classes of roughly the same size, irrespective of the computing and associated technology which supports them.

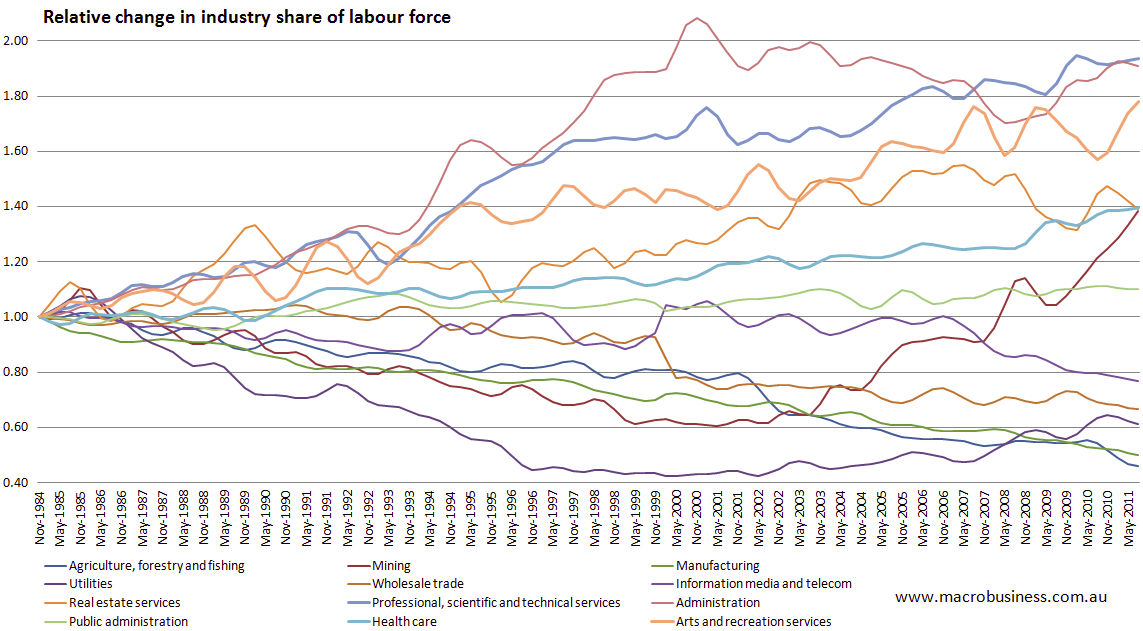

We can see the long term trends in the graph below. Healthcare, arts and recreation, and professional services have increased their share of the labour force substantially over the past 27 years. Meanwhile, areas of the economy where productivity growth is high, such as agriculture, manufacturing, wholesale trade, and utilities, have required a much smaller proportion of the workforce over this period. Of course Baumol’s disease describes long term trends which act in parallel to patterns of regional displacement of tradable industries to cheaper foreign markets. In the short run many other factors are also at play.

Unfortunately most economists fail to acknowledge Baumol’s disease when analysing changes in the economy. You won’t find a mention of it in the media (just two results when searching Google news), and you will find plenty of confused ideological articles about modern poverty and flatscreen television. How can someone live in poverty with a flatscreen television, a coffee maker and a DVD player? Simple. These goods are becoming relatively cheaper over time, while other fundamental goods and services – health, education, food and housing – are becoming more expensive. In fact, I could buy a flatscreen, a DVD player and a coffee maker for about the cost of four days rent or a week’s groceries for my small family. This is an important consideration in analysis of the changing cost of living.

Sensible economic discussion needs to catch Baumol’s disease. Without it we cannot properly analyse the influence of short term political and financial factors against a backdrop of structural changes in labour markets and prices as a result of productivity growth in some areas of the economy.

Thank you Yves for sharing.

This article is proof again of why NC is the single most outstanding blog this side of the galaxy.

Friends;

Absolutely right on here. I’ve never, in my admittedly unprofessional reading methods, come across mention of Mr Baumol and his insights. Would this be another example of Professor Chomskys’ “Manufacture of Consent?” Or is it an artifact of ‘Groupthink,’ as Professor Feynman illustrated in his Appendix to the “Challenger Accident Report?” Making this distinction, I suggest, would shape our reactions to present events profoundly. Are we Sheep, or just members of a Flock?

As I keep asserting; You, dear Hostess, are a (thankfully) Unregulated Utility.

fantastic post. Makes the student debt figures (see link below for some awful graphs on their recent size) just seem like a complete failure of society.

http://www.thereformedbroker.com/2011/09/15/the-student-loan-bubble-illustrated/

It’s quite OT, but I’d like to stress that the “Baumol effect” is just another way to state the Labor Theory of Value:

At long term equilibrium, the relative cost of goods is proportional to the amount of labor needed to produce the same goods (ie, if 5h of labour are needed to produce an apple, and the apple costs 10$, and 3h of labor are needed to produce a DVD reader, the DVD reader will cost 6$).

Exactly, and that’s an important point.

People have been confused about Marx’s “Labor theory of value”, because it didn’t seem to hold true. But it *does* hold true over the long run — the *very* long run of centuries. It simply doesn’t show up at less than very long timescales, only occasionally being visible over mere decades.

Very clean and entertaining presentation of this Baumol disease

Everybody working in a competitive environment is aware of this … But the massive economic costs associated with it are certainly under-appreciated.

The disease has no cure. I do not buy it entirely … except for finance and banking of course:)

Pay a visit to the Netherlands, a relatively tightly-knit country with both an effective health system and a decent educational system. IMHO costs are under control. At least on a comparative basis with country such as mine or yours!

The ‘disease’ lies in the fact that the musician gets more pay without playing more notes or playing more often.

That does not imply that the cost of the orchestra cannot be kept under control, but that is a separate issue.

I was on verge of giving up on economics as book after book and papers seem to give useless information in alien concepts and languages I could hardly comprehend.

Thank you Yves for providing articles I can intuitively understand.

Great read.

Upon reflection though there are ways to improve productivity in health care and in education (2 of the major service areas), it is just that entrenched interests do not want to make the changes.

In health care first up we have the obvious facts that say the Canadian system is far cheaper to run than the US systems and gets better overall results. A switch to single payer in the US would cut costs.

In health care as well, technology has made doctors somewhat overqualified for what they do. Someone doing routine surgery these days is not that much different than a mechanic (I have a surgeon friend who says basically he is just a trained monkey). Very standardized procedures, just “paint by numbers”. Many many doctors are quite simply overpaid. And that is not even to mention the possibilities for increased use of less “qualified” (though more specialized)staff such as NPs.

In education technology and innovation also allows us to improve efficiency. I am currently studying Spanish but I would never consider attending a “class” – waste of time. I use resources on the net and study when I want (more than if I went to a class).

In schools you could have increased use of co-op (kids spending time in the workforce at a younger age), more volunteers in the classroom (especially seniors), and the use of older kids to help younger kids. These recognize that school has become a babysitting service (all kinds of useless curriculum) in an environment where one teacher standing and talking to 30 kids (who are sued to a fast flow of information) just does not cut it anymore. Kids unleashed (with guidance) can learn far faster and far better than school currently allows.

Let’s take this to its logical conclusion. Eventually, if mankind is successful enough, all production will be automated and we will be free to spend our time producing arts and other luxuries. Under Baumol’s analysis, this would be perceived as a cost-increase for the less productive artists. Not necessarily a bad thing.

Also, I disagree with the conclusion that education and healthcare need to get more expensive. The theory seems to make room for the possibility tha these sectors can also become more productive, squeezing the price-increases into some other unproductive sector (hopefully the arts!)

Exactly. It’s actually a good thing that more and more sectors require less and less labor, and we can spend more and more of our time on avocations.

Rising price of labor relative to goods — “Baumol’s disease”, is on the whole a *good* thing.

It’s important to expect it, of course.

Unfortunately, the science fiction authors who predicted this decades ago did not live to see their vision come to pass.

Baumol might be the most underated economist inthe world today. Perhaps only second only to Ralph Gomory, whom he teaches and works with. Together they re conceptialzed

Ricardian equivalence proposition .

I am surpirsed that Ralph’s postings at The Huffington Post have never been linked to here at NC. Have a look at is article entitled “The Innovation Delusion”…….

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ralph-gomory/the-innovation-delusion_b_480794.html

In the United States, innovation has become almost synonymous with economic competitiveness. Even more remarkable, we often hear that our economic salvation can only be through innovation. We hear that because of low Asian wages we must innovate because we cannot really compete in anything else. Inventive Americans will do the R&D and let the rest of the world, usually China, do the dull work of actually making things. Or we’ll do programming design but let the rest of the world, usually India, do low-level programming. This is a totally mistaken belief and one that, if accepted, will consign this nation to second- or third-class status.

The latest offender to advance this line of thought is Thomas Friedman, who has prominently displayed this familiar and entirely incorrect line of thought in the New York Times. Unfortunately, this idea is one that is widely accepted without careful thought about either its truthfulness or its consequences.

Truth and Consequences

Cheap labor abroad is cited as the incurable handicap that explains why the United States cannot compete. But cheap labor doesn’t explain the fact that Japan and Germany, both high-wage countries, are successful in the automobile industry. Nor does it explain how semiconductors, a model of a high investment, low-labor content industry, are mainly made in Asia. The premise that the inescapable burden of competing against low wages means failure is simply not correct.

Perhaps even more disturbing than the lack of truthfulness is the fact that we are not addressing the consequences of not competing. There are some inescapable truths about any economic good, be it a manufactured good or a service: (1) you either produce it in your own country, (2) you trade something you do produce for it, (3) you do without it, or (4) you import it and promise to pay later.

We are moving steadily away from producing what we need in this country. We are also moving away from producing on a scale that enables us to trade for what we do need. Rather than do without, we are increasingly importing things with a promise to pay later. This cannot go on. When our trading partners, especially China, no longer want to loan us hundreds of billions of dollars a year to be paid later, we will have little productive capacity left and we will be a poor nation.

Friedman is only the latest to assume that we can avoid this fate by emphasizing designs, ideas, and R&D and trading them for the items we need. This is an attractive idea; we often hear about innovation parks and university research centers and often their work is both exciting and good.

But the chasm-sized flaw in this otherwise alluring proposition is scale. Balancing trade on ideas and R&D simply cannot be done. The most elementary analysis shows that the scale is entirely wrong. As one who spent many years as the head of research of a large corporation, I know how much R&D matters; I also know how small it is. Eight percent is a very large percent of revenue to spend on R&D. Even in manufacturing, which is relatively R&D intensive, 4 to 5 percent is typical. It is really wrong to think that you can scale up R&D to be big enough so we can trade it for the huge quantity of things we need but don’t make in this country.

A Strange and Unworkable Strategy

Ignoring the issue of scale, Tom Friedman goes on to quote authoritative Chinese sources who say that by the end of the decade China will be dominating global production of the whole range of power equipment. To Friedman’s approving eye this just means that China is going to make clean power technologies cheaper for itself and everyone else. Friedman says that Chinese experts believe it will all happen faster and more effectively if China and America work together with the United States specializing in energy research and innovation, at which, he asserts, China is still weak, while China will specialize in mass production.

It is probably true that all this will happen faster with the specialization Friedman describes, but where will we be at the end of that process? China will be making power equipment cheaply, but the chasm is still there, so what will we have to trade for it? Power equipment will be cheap in China, but if we adopt this approach it may well be unaffordable in the United States.

Meanwhile the Chinese wisely welcome our nascent innovations and turn them into products. They are building plants, making things manufacturable, and adding them to their growing GDP. Friedman’s article contains an excellent example of this. He describes a U.S. developer with a new approach to solar-thermal power, whose proposal to the U.S. government asking for small scale support was easily outbid by a Chinese offer that was far larger and was aimed at much larger scale plants.

Specializing in R&D, but sending its fruits on to others is a strange and completely unworkable strategy for a nation.

Other Issues

Thinking of innovation as a standalone activity without production has other major flaws. First, our global corporations, understanding that innovation and production are in fact closely tied, are rapidly moving not only production but also R&D overseas. Intel’s CEO made this very clear when he said that the goal of Intel’s new plant in China is to support a transition from “manufactured in China” to “innovated in China”.

In addition, the standalone innovation approach leaves most Americans entirely out. After all, only a very small portion of Americans are engaged in R&D. At a recent meeting I heard “The only thing that matters is innovative and passionate people.” These people do matter, but they are very far from being the only ones. This attitude misses the point that it was all our people, working in many different work settings, that made this country prosper. And all of them will all be needed in any viable future for our country.

What We Must Do – The Role of Trade

We need successful industries and we need to innovate within them to keep them thriving. However, when your trading partner is thinking about GDP rather than profit, and has adopted mercantilist tactics, subsidizing industries, and mispricing its currency, while loaning you the money to buy the underpriced goods, this may simply not be possible.

The ability to compete in a world that is half-mercantilist, half-free is inescapably tied to effective trade policy. Our present policy is to beg. We ask countries like China to stop the subsidies and currency mispricings because they are creating a one-way flow of underpriced goods; goods that are destroying jobs on a large scale in many of the most productive sectors of our economy. But why should they stop? It’s working for them.

We must move to balanced trade. With balanced trade every dollar of imports is matched by a dollar of exports of goods or services produced here in the U.S.A. We are fortunate that there are in fact ways to balance trade. One very attractive way is to adopt some version of Warren Buffet’s Import Certificates plan, which Buffet has described in a remarkably insightful Fortune article.

We should act now to balance trade. We should not continue to beg while jobs disappear and our productive ability erodes.

What We Must Do – Motivating our Companies

Today our companies are motivated to take innovations abroad, produce there and import the goods into the United States. Increasingly we can expect services also to go overseas. We must produce here in the U.S.A., to employ the people of this country, and we must keep their activities effective by a steady stream of innovations in design and production. While other countries roll out a welcome mat of tax breaks and subsidies for our companies because their common sense tells them that their people being employed in productive work is the road to being a rich country, we provide no incentive for U.S. companies to produce here.

We cannot continue to have our corporations, faithful only to the interests of their shareholders, engage in a one-way flow of jobs, technology, and innovation out of the country. We need to realize that with globalization the interests of our country and of our global corporations have diverged. We can realign the interests of corporations with those of our country by rewarding companies that are productive here. And that can be done in ways that are consistent with our history and with the limited capabilities of our government.

Conclusion

Specializing in innovation is an attractive idea, but a misleading one; an idea that blinds us to what we really need to do.

We need to do more than produce exciting new ideas; we must also be able to compete in large productive industries. This requires us to both balance trade and to motivate our corporations not only to innovate, but also to produce in this country. While this is hard to do, it can be done. Specializing in innovation, though often recommended, is in fact a delusion, an alluring path that in reality will lead us straight downhill.

Glen, excellent comment. Thanks!

Dan, I think you maybe comparing apples to oranges.

The way I understand it is, imagine a basic washing machine produced 1n 1960 with no bells and no whistles. Let’s say one of the last assembly operations is painting the machines white and in 1960 it required 15 painters. Now, assume robotic painters are introduced, and to paint the identical model (assume no added or improved features) it requires 2 robotic operators. This would be considered a productivity gain.

For music, I think a CD recording is an entirely different product than attendance of a live performance. The live performance still requires the same number of musicians and a conductor, so there is no productivity gain in providing a live concert.

And I see on-line education as an entirely different product as well, at least for children. Part of the attending school is the socialization process. 1 teacher to watch and supervise the children’s behavior, assign homework, monitor their progress, etc. It still takes 1 teacher (well maybe a union president and several administrators now, ha ha) to provide the same educational service, so there is no productivity gain for the same service that was provided 20 years ago.

At least that’s how I read this.

My apologies, this was directed to Dan Duncan’s comment.

The only way we’re going to get balanced trade is when international trade is settled in gold. We need gold’s honest discipline for that. I’m not holding my breath, but I do think it will happen (eventually).

Why is it called a disease? It just looks to me like an expression of the fact that just because we recently got better at making widgets, we don’t actually want more widget makers. And we (including the lucky widget makers) really don’t want fewer violinists. So whenever we are in danger of running out of violinists (because they’re all running away to make widgets for higher wages) we have to offer the violinists some of our widget money. Which, thanks to the increase in productivity, we can afford to do!

What this mainly tells me is there’s no such thing as a good wage freeze, even in someone else’s sector of the economy. The bell tolls for me whoever is getting his union rights hammered, because the Baumol effect works both ways: if miners are laid off and desperate for work, my wages will not rise until the market is short of workers again, even though I’m not a miner. Rising wages come from employer profits, never from other workers’ falling wages.

JimS:Why is it called a disease?

Excellent point.

I’ve long been aware of this phenomenon, although I didn’t know it was attributable to Baumol (one more reason to respect the guy). Still I’m glad that Yves posted this “tutorial” as it’s an effect that’s often overlooked.

But a disease? No, a phenomenon that’s no more pessimistic than the laws of thermodynamics telling us we can’t get something for nothing.

While the potential efficiency improvements in say education are far less than in say manufacturing, it doesn’t mean doom and gloom. The ratio of teachers to manufacturing workers rises over time? So what. For a given level of education it doesn’t mean teachers have to increase as a percentage of the workforce or that education costs have to increase as a percentage of GDP.

And while there are certainly inefficiencies, turf building/defending, etc. in education (as in any other field), increased productivity in other fields _should_ mean that we can afford to devote more resources to education, and I think we should do so if it actually improves education.

It’s a disease because it implies we will simply not be able to afford health and education past a certain point, as those things take up an increasing share of national income.

No it doesn’t. It says that as, for example, manufacturing productivity increases and, for example, educational productivity doesn’t change, then for fixed levels of manufactured goods and education, education will become more expensive _relative_ to manufactured goods. But thanks to improvements in manufacturing productivity, you’re still left with greater “prosperity” (production possibilities). You can use that to buy more manufactured goods than in the past, or more education, or more comic books, but it does not leave you poorer.

“To make any progress in the provision of health care all sides of politics need to acknowledge that the cost of health care MUST rise over time relative to other goods and services if the economy is experiencing any form of productivity growth (noting the current temporary decline in productivity growth in Australia).”

Huh? The point about the health care sector in the US is that it costs us more than 15% of GDP, whereas from international comparisons and studies of what we actually get from that spending (ie, much of it is waste, and not just because of the crazy insurance system) we could get basically the same results spending say 8% of GDP.

Think about listening to Mozart…back in the day of Mozart….

–You had to be rich and connected.

–You had to go to a live performance.

–Unless you lived in Vienna, you heard his music one time. Think about how different musical performances were prior to the advent of recording devices….

The fleeting note. The End.

[Sure, you might hear a local outfit attempt to recreate the score, but these were nothing more than non-caricatured pre-Elvis impersonators doing Amadeus.]

I have 2000 songs in the palm of my hand and you’re underestimating productivity increases in music.

[I ain’t sayin’ its necessarily a good thing, but nobody gives a shit about quality, so there it is.]

As to education…The world’s libraries are at our finger-tips and the best instructors are available on demand.

Let’s say, for example, one is foolishly enamored with MMT. This person could go to Paul’s online math instruction, take a course in pre-Algebra, and save herself a lot of embarrassment. It’s all there and you’re underestimating productivity in education.

Healthcare, of course is a bit trickier. But one area with real potential for a productivity increase is with Prevention. Prevention is about “getting the message out”. Every day, we get new tips, new insights on ways to improve our health.

And the treatment for simple maladies or answers to simple questions, that in the past, would have necessitated an unproductive, inefficient trip to the doctor are also handled more efficiently outside the System. Productivity has increased here as well.

Baumol’s Disease is looking at Productivity with a closed mind.

Mr Duncan;

I suspect that you are viewing Productivity from the wrong vantage point. Yes, I admit, many previously labour intensive processes have been automated. However, and it’s a big however, as the Pentagon learned to its’ cost in Iraq, ‘boots on the ground’ were irreplaceable for certain key pieces of the puzzle. There are limits to cybernetics, period. Which leaves us grappling with the Human Mind.

In education, everyone I have read who has taken an unbiased look at it agrees, a ‘good teacher’ is the ‘gold standard’ for quality and outcome. Volume and quality of data have no direct impact on motivation to use such data. One of the great advertising geniuses of the Twentieth Century was Goebels, and look how his career ended.

I would suggest that we have to approach this problem from a global perspective. Macroeconomics at its’ best.

YS:

Thank you. I had forgotten about this.

If one really wants to understand market economies, Robin Hahnel and Michael Albert’s 1991 Princeton Press book “Quiet Revolution in Welfare Economics” is crucial.

This is a most interesting article. If you look at the idea in terms of a self contained national economy it makes good sense that in order to maintain quality of life, economic gains have to be balanced across all necessary functions. What I wonder about is how this might be applied to the present global picture where the sectors with rising productivity are being moved to other national economies. That would seem to make the balancing act a lot more complicated.

we call wages in biz costs, but they really are a part of profit, ever bit as much (more?) than normal net. this is not a disease, it is health, and based on the reality that increased productivity is not owned but part of the maturity of a society and shared.

A few points, some of which have already been raised.

First, despite Philip Pilkington’s rather silly assertion that “From an economic perspective you cannot measure LTV” we have another group who don’t seem to have any difficulty in measuring labour — and this group consists of economists.

Second, as Random lurker pointed out above, the entire riddle seems to be built on a labour theory of value. To wit: since the productivity of a musician’s labour hasn’t increased, why should their wages — that is, the price paid for that labour. While this is one step removed, focusing on the productivity of the labour rather than the labour itself, the underlying assumption is that a certain amount of labour productivity has a specific monetary value and if the productivity doesn’t change, then neither should the monetary value. That is, musicians should be earning exactly the same now as they were a few centuries ago. The fact that this would leave them to basically starve to death is apparently just one of those things.

Now, as I understand it, modern economics rejects the idea of intrinsic value, arguing instead that economic price is determined by factors such as supply, demand and preferences. Thus, the productivity of a musician is irrelevant. Musicians possess a particular set of skills; if you want someone with that set of skills, you have to offer enough to attract those who have those skills, which means you have to offer wages that are competitive with all the other activities such individuals could be engaging in. Further, you have to offer wages that are sufficiently attractive that people will regard it as a worthwhile investment to acquire that set of skills. The fact that exercising that set of skills has the same level of productivity now as it did a few centuries back would have no influence on the matter.

As far as I can tell, William J Baumol has just identified a particular instance of how economists expect the market to work and discovered that, gosh, that’s how it works.

Third, the fact that the market works as it’s expected to is cast as a problem, called a “disease” and the question is raised how do you cure it?’ That is, I presume, how do you force wages down to what they ‘should’ be based on productivity? Again, the fact that this would lead to a whole bunch of people not being able to earn enough to afford food and so would presumably just starve to death being, again, just one of those things.

Odd how a variant of the labour theory of value is alive and well when it can be used to suggest some workers should be earning less, but is somehow that same theory is magically rendered invalid when used to argue that some workers should be earning more.

Fourth, and finally, the productivity/wages riddle is cast in terms of musicians and teachers and health care workers, rather than in terms of managers, financiers and administrators, all of whom also work in labour-intensive areas (a different sort of labour, perhaps, but still labour) and whose productivity has also not shown any great improvement over the past few centuries. How come the question isn’t: ‘How come they’re earning so much given that they’re productivity is pretty much the same of their nineteenth century predecessors? Maybe we need to cut their salaries back to 1800 levels?’ A rather interesting bit of framing there.

I think you have missed the point of the article. It’s really not about driving down wages – it’s simply an observation about how the economy works. It tells us that economic growth can actually make important things less affordable.

Did I? The framing seems quite specific. The fact that a musician’s wages have gone up is cast as a “problem”, the phenomenon that causes that rise is described as a “disease”, and the point is made that “the disease has no cure”

As far as I can tell, if the musician’s wages hadn’t risen, there would be no problem and if those wages could be forced back down to where they were — with the implication of that’s where they should be given the level of productivity — the disease would be cured.

Something that’s only an observation about how an economy works does not use that kind of loaded language. You only frame an observation that way if you people to think about the phenomenon in a specific way and to predispose them to a particular type of solution.

After all, if someone talks about the ‘plague’ of gay marriage and how it’s ‘infecting’ society it’s not invalid to infer that they are probably opposed to the idea and would like to see gay marriage banned.

If it’s just an observation, then much more neutral language is called for.

Yes, calling the Baumol effect a disease, has a history: at other times and places the same phenomenon has been called “the servant problem”, “the labor shortage”, and “wage inflation”.

Of these, “wage inflation” probably the least pejorative, but even so I think a more neutral terminology is needed.

If anything, the other historical terms have an even stronger emphasis on the idea that certain people are simply being paid too much — and by “certain people” I mean members of that class that would be servants.

This sort of framing seems to completely ignore that the exact same phenomenon is responsible for the rising salaries of those who are likely to employ servants. Somehow that’s not seen as a problem — even though the phenomenon is used extensively as justification for the high salaries paid to CEOs and is trotted out whenever politicians vote themselves a pay rise. As they are so fond of telling us, you have to offer competitive rates of compensation, otherwise all those executives would be off working on an assembly line making widgets or some similar occupation that has had significant productivity rises. If you pay peanuts, you get monkeys and that sort of thing.

The classism in these terms is blatant and really should be retired along side similar terms which reflected the sexism, racism and homophobia of times past. If used in a historical context, they might be valid, but their continued use just displays a naked attitude of class warfare.

Of course, if you believe that we are actually in the middle of a class war, then the term can be seen as a Freudian slip rather than as a historical holdover.

What about politicians? Are they in an unproductive sector?

They seem to be doing pretty the same as their predecessors in the 19th century and yet, they are making a lot more.

Actually, Baumol seems to be missing something important: The improved wages of the laborers working in the productive sectors allows them to BID UP THE PRICES of everything else, until they have squandered all of their relative gains.

I think the health care connection needs some work. Health care is an area with great strides in productivity, but the productivity gains often come with additonal costs such as:

*patent protection of drugs

*longer living clients due to productivity and technology gains which leads to more tests and more new technology

*as some machines replace labor, new technology requires a different type of labor

Education is a little more simplified, so I can almost understand the author’s point here. But even education is not very static. Education costs, especially at a university, rise because of increasing administration layers, better living conditions (e.g. state of the art rec centers), computer and IT needs, larger number of departments (do we really need an Asian Studies Dept?), etc.

We cannot shrug our shoulders and say, oh well, the state needs to step in and subsidize these out of control areas. The state has a more valuable role in trying to control the costs and limit the “exuberance” in these areas. Why is a Plavix pill in the US 2x the cost as in any other country? Why can’t a university (public or private) provide top notch education in a stripped down environment without the bells and whistles?

These are important questions. I’m not doubting Baumol’s disease, but I am questioning the economic sectors targeted here.

“Interprofessional wage arbitrage as a result of productivity changes” would be a one sentence definition of this. I would assume the magnitude of this affect is constrained by employment levels.

As somebody else mentioned, wage arbitrage doesn’t transfer accross borders effectively. Is it because of the different currencies, regulations, capital controls, immigration limitations? Probably most importantly is the last.

Thank you Yves. on a similar train of thought, this helps to explain our argument over inflation and deflation related to QE aweek ago.

Item’s which cannot be affected by productivity changes represent the true scarecity of resources, or conversely the excess of money “in the system”, which is why I look to commodity prices to represent the true inflation not prices of flat screen tvs (i.e. CPI).

Hence my argument that we do have high inflation as seen in commodity price changes which occurred concurently with loose monetary policies, even though there is no apparent direct mechanism to have cause it.

They don’t measure productivity in terms of how many apples you have grown.

They measure how much money you got for your apples and divide that by the hours you put in.

So, if an ex-politican charged $500,000 for one one-hour speech before but she charges $2,000,000 now, that’s not Baumol’s disease. We don’t measure her productivity in terms of 5 speeches/yr. We measure it in terms of money. So, we say her productivity is 400% higher…maybe 399% after adjusting for inflation.

I know, I know. That’s hard to believe, but productivity gain is the percentage chage in GDP per hour of labor.

On the other hand, you could say, it’s all inflation caused by price gouging. But since they believe in the tyranny of One, where every complex phenomenon is redued to one, which, in this case, is the CPI, you don’t see the higher fee as inflation caused by gouging. You say instead, hey, she is more productive!

What about Ponzi schemers?

They do the same bascially now as they did before.

But instead of swindling $1 million 100 years ago, they get $20 billion in the 21st century.

I think that’s what you call improved productivity.

The lesson that I take away from this is integrating more highly productive industries with the general economy has a positive spill-over effect that lifts the general condition of everyone in the economy.

In theory, given advances in technology, we should be able to produce the same level of production at any point in the future, with fewer labor dollars and less material waste. Companies should be more profitable (produce more at less costs), thus paying more taxes even at the same tax rate.

The only thing missing is the impact of gloablization. With high productive industries located off-shore, the additional profits and related tax revenues (how we afford the services) from technological advances accrue to multi-national corporations and their host countries. In addition, off-shore host countries experience the benefit of additional capital investment in technology and physical assets (new plant construction, office towers, transportation equipment, IT, etc.). Add it all up, and you understand why our economy has stagnated and developing economies have boomed.

Personally, I can see some of the advantages of global trade. And I have nothing against the people in developing countries. I just think we should have trade policies that benefit all of the people of our country, not just an elite few. Trade policies that balances our employment and our own economic health against Wall Street investor profits. Surely, we can develop more sensible policies than we have in the past. Win-win policies

Baumol’s ‘disease’ is inevitable in an economy where the returns to labour and capital are relatively fixed, as first noted by Bowley.

If returns to workers in manufacturing decline, but total returns are fixed, then returns in other areas such as services must increase. See for example fig 3 in Young 2010:

http://gesd.free.fr/young5.pdf

The explanation for the relative stability of labour’s share or returns turns out to be trivial. See ‘The Bowley Ratio’:

http://arxiv.org/abs/1105.2123

More speculatively, it appears that increasing debt changes the ratio of returns to capital (section 4.6):

http://www.econodynamics.org/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderfiles/commacro.pdf

Once again I’m too tired to read all the comments so if I repeat other arguments, then forgive me.

As for “confused ideological arguments” I got a really good one. King Henry VIII didn’t wear “Air Jordans”. Here’s another that we all understand first hand, dentistry without anesthetics. If you have read the “Buddenbrooks” by Thomas Mann (I only read classics because they make you realize nothing has changed) you would remember he goes from a tooth extraction to the final demise of the family after collapses on the street from an an infection and overworkism. Thank god for modern dentistry.

So I would say that Baumal’s disease is deflation. I totally get Yves’ argument that over time, technology improves and we get more for less, but we don’t get more services for less. It’s a tough argument. All I can say to that is dentistry, bypasses, genetic therapy. To say “health care costs” are static is BS. To say you can’t get more out of a classroom with an Ipad is BS. The percentages may not be equal, but it’s not like I’m paying for tooth extraction without anesthetic because dentistry is static.

That’s all I got. I wanted to got to the logic of hedonic adjustments in light of this argument, but I pose the risk of rambling at that point.

Scott

“but we don’t get more services for less.” makes no sense. The correct statement is that it is incorrect to say that “we don’t get more services for less.” We still get more services for less. I get the cost as a percentage of total spending argument, but I’m not settled on that one yet. The tone of the article states that productivity gains in education is a dead end and that’s what I’m arguing against.

Just to prove I have ‘tude. Where else can you read a Harvard grad write every day? Where else can you read a good writer and an experienced professional? For a layman, education is more available today than ever before. If the cost is going up percentagewise then someone is missing the point.

This sounds like the Balassa-Samuelson effect to me, which could be one reason why “Baumol’s disease” is not mentioned so much. It may also explain to some extent why income inequality has increased. To the extent that the sectors without improving productivity are more open to international competition, their relative wages fall behind – for example local agricultural labourers are undercut by migrants.

“To the extent that the sectors without improving productivity are more open to international competition”

I’m afraid your explanation doesn’t hold water. Manufacturing has had dramatic productivity improvements and yet is very subject to international competition.

My explanation of what?

“Bargaining between workers and businesses in each sector (including government sectors) equalises wages over time. Thus productivity growth in just one area of production is shared amongst workers across the economy”

Sorry Yves, but this piece is painful to read because it neglects to inform your non-Australian readers the most salient fact about the Australian labor market– its annually adjusted minimum wage.

As of June, it is A$15.51 (US$$16.04) per hour. In contrast, our minimum wage is US$7.25 (A$7.01) per hour and will only rise upon Act of Congress (good luck getting that bill through the House). A constantly rising minimum wage is the mechanism by which productivity growth in Australia is “shared amongst workers across the economy” in contrast to the American practice the last three decades of being shared amongst the top 1% of earners.

http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2011/09/great-prosperity-1947-1977-vs-great-regression-1981-present/

Couple of points:

1) Isn’t it precisely the bargaining power of those who work for a living that has been under sustained attack? Why in theory couldn’t both corporations and governments keep doing exactly what they’re doing, i.e., squeezing for all they’re worth, so long as there is nowhere else for these people to go economically? I don’t see how Apple et al are helping these guys much.

2)Isn’t there a very big difference between those employed in areas like arts and recreation, health care, education, and professional services and those growing tens of millions by far the worst hit whose labour has been so devalued the legal floor is in the sub-basement?

3) We very badly need to re-think what we even mean by “productivity” if we are ever to engage or re-engage as full social and economic participants roughly 2 quintiles of the population. In my mind, the best way to do this is reverse technological “advances” in areas where the “advance” has been most lethal to labour: agriculture, forestry, non-mega construction, manufacturing, textiles etc., rather than a million variants of service Mcjobs where the labour is worth so little precisely because it has so far removed from the production of anything non-discretionary. The added bonus is environmental sustainability. This will obviously mean less for the top 3 quintiles. Well, so be it.