Yves here. It has been striking how little commentary a BIS paper by Claudio Borio and Piti Disyatat, “Global imbalances and the financial crisis: Link or no link?” has gotten in the econoblogosphere, at least relative to its importance.

As most readers probably know, Ben Bernanke has developed and promoted the thesis that the crisis was the result of a “global savings glut,” which is shorthand for the Chinese are to blame for the US and other countries going on a primarily housing debt party. This theory has the convenient effect of exonerating the Fed. It has more than a few wee defects. As we noted in ECONNED:

The average global savings rate over the last 24 years has been 23%. It rose in 2004 to 24.9%. and fell to 23% the following year. It seems a bit of a stretch to call a one-year blip a “global savings glut,” but that view has a following. Similarly, if you look at the level of global savings and try deduce from it the level of worldwide securities issuance in 2006, the two are difficult to reconcile, again suggesting that the explanation does not lie in the level of savings per se, but in changes within securities markets.

Similarly, the global savings glut thesis cannot explain why banks created synthetic and hybrid CDOs (composed entirely or largely of credit default swaps, which means the AAA investors did not lay out cash for their position) which as we explained at some length, were the reason that supposedly dispersed risks in fact wound up concentrated in highly leveraged financial firms.

By contrast, the Borio/Disyatat paper tidily dispatches the savings glut story, and develops a more persuasive argument, that the crisis was due to what they call excess financial elasticity, which means it was way too able to accommodate bubbles. From Andrew Dittmer’s translation of the paper from economese to English:

The idea of “national savings” or “current account surplus” refers to the total amount of exports sold minus the total amount of imports sold (more or less). The “excess savings” theory holds that this excess had to have been financed somehow, and so presumably by countries in surplus, like China.

However, for the US in 2010, the total amount of financial flows into the US was at least 60 times the current account deficit (9), counting only securities transactions. If this number were correct, then inflows would be 61 times the current account deficit, and outflows would be 60 times the current account deficit. The current account deficit is a drop in the bucket. Why would anyone assume it had anything to do with the picture at all?

Moreover, if the “savings glut” theory was correct, we would expect there to be certain historical correlations between the following variables: (a) current account deficits of the US, (b) US and world long-term interest rates, (c) value of the US dollar, (d) the global savings rate, (e) world GDP. There aren’t (4-6, see graphs).

You would also expect credit crises to occur mainly in countries with current account deficits. They don’t (6).

Suppose we look at a more reasonable variables: gross capital flows (13-14). What do we learn about the causes of the crisis?

Financial flows exploded from 1998 to 2007, expanding by a factor of four RELATIVE to world GDP (13), and then fell by 75% in 2008 (15). The most important source of financial flows was Europe, dwarfing the contributions of Asia and the Middle East (15). The bulk of inflows originated in the private sector (15).

If we look instead at foreign holdings of US securities (15-16), Europe is still dominant, but China and Japan are a little more prominent due to their large accumulations of foreign exchange reserves (15). Still, the Caribbean financial centers alone account for roughly the same proportion as either China or Japan (16). Other statistics provide a similar picture (17-19).

So what caused the crisis? Clearly, the shadow banking system (mainly based around US and European financial institutions) succeeding in generating huge amounts of leverage and financing all by itself (24, 28). Banks can expand credit independently of their reserve requirements (30) – the central bank’s role is limited to setting short-term interest rates (30). European banks deliberately levered themselves up so they could take advantage of

opportunities to use ABS in strategies (11), many of which were ultimately aimed at looting these same banks for the benefit of bank employees. These activities pushed long-term interest rates down. Short-term rates remained low because the Fed didn’t raise them as long as inflation didn’t appear to be an issue (25, 27).The Asian countries played a small role as well. They didn’t want US/European-driven asset price inflation to spill over into distortions in their economies, and so they protected themselves by accumulating foreign exchange reserves (26 and 26 note). That was mean of them. If they had allowed more spillover, then the costs of the shadow banking system would have been partly borne by them, and that would have made the credit crisis less severe in the advanced countries (26).

Keep in mind that this is not a mere aesthetic argument. If you believe the Bernanke argument, you’ll argue that China needs to let the renminbi appreciate faster and provide more safety nets to its populace so they can shop almost as much as Americans do. If you accept the Borio/Disystat analysis, it means you need to regulate financial players and markets far more aggressively.

This VoxEU article by Hyun Song Shin provides further support for the Borio/Disytat thesis, as well as providing the additional benefit of providing a clear and simple explanation of some of the issues it raises.

By Hyun Song Shin, Professor of Economics at Princeton. Cross posted from VoxEU

It has become commonplace to assert that current-account imbalances were a key factor in stoking subprime lending in the US. This column says the ‘global banking glut’, i.e. the rise in cross-border lending, may have been more culpable for the crisis than the ‘global savings glut’. As the European banking crisis deepens, the deleveraging of the European global banks will have far-reaching implications not only for the Eurozone, but also for credit supply conditions in the US and capital flows to the emerging economies.

The ‘global savings glut’ is what Ben Bernanke called it. This phrase provided a powerful linguistic focal point for thinking about the surge in net external claims on the US on the part of emerging economies. The biggest worries concern the financial stability implications of these large and persistent current-account imbalances.

Since Bernanke’s 2005 speech (Bernanke 2005), it has become commonplace to assert that current-account imbalances were a key factor in stoking the permissive financial conditions that led to subprime lending in the US.

But maybe the finger is being pointed the wrong way. My recent research suggests that the ‘global banking glut’ may have been more culpable for the crisis than the ‘global savings glut’ (Shin 2011).

What is the ‘global banking glut’?

To introduce the distinction, it is instructive to start with the financial crisis in Europe. What role did current-account imbalances play there? There are some superficial parallels with the US in the run-up to the crisis.

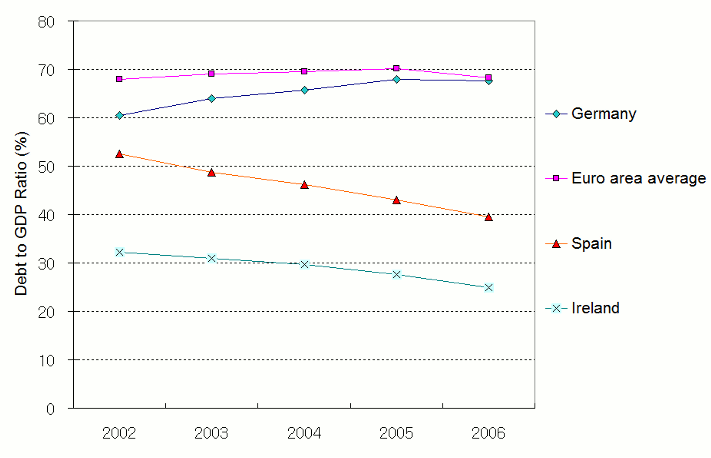

The current-account deficits of Ireland and Spain widened dramatically before the crisis (Figure 1). This despite the fact that Spain and Ireland were paragons of fiscal rectitude – with budget surpluses and low debt ratios (much lower than Germany’s and the Eurozone average in 2006, see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Current account of Ireland and Spain (% of GDP)

Figure 2. Government budget balance and debt-to-GDP ratios of Ireland, Spain and Germany

To push the analogy with the US further, imagine for a moment that the Eurozone is a self-contained miniature model of the global financial system. In this miniature model, Germany plays the role of China, while Spain and Ireland play the US.

According to the analogy, excess savings in Germany find their way to Spain and Ireland where they inflate the property bubbles there. The bubbles subsequently burst, resulting in the socialisation of private debt through bank bailouts and precipitating the sovereign-debt crisis.

However, the further we push the analogy, the stranger it gets. According to the ‘global savings glut’ hypothesis, Chinese savers favour US Treasuries because China lacks deep financial markets that could cater to demands for safe assets. In the miniature model of the savings glut for the Eurozone, Spanish and Irish bank deposits play the role of US Treasuries, since current-account imbalances in the Eurozone were financed through capital flows in the banking sector. To sustain the analogy, we would need to argue somehow that German savers shunned bank deposits in Germany to favour bank deposits in Ireland and Spain. Why would German savers believe that deposits in Spain and Ireland are safer than those in Germany? At this point, the savings glut analogy strains credulity and breaks down.

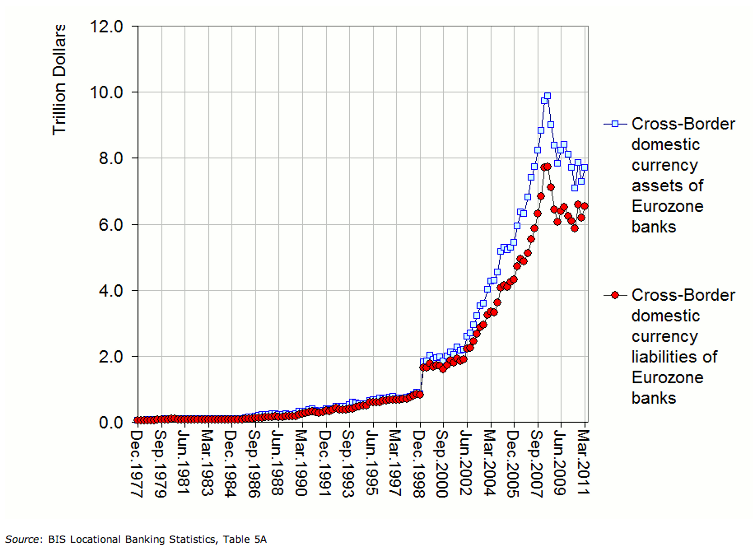

A more plausible narrative is a banking glut associated with the explosive growth of cross-border lending in Europe, as illustrated by Figure 3 which plots the cross-border domestic currency lending and borrowing by EZ banks.

Figure 3. Cross-border domestic currency assets and liabilities of EZ banks

There is a mechanical jump in the two series at the start of 1999 with the launch of the euro, as previously foreign-currency lending and borrowing are reclassified as being in domestic currency (i.e. euros). But from 2002, cross-border bank lending saw explosive growth as the property booms in Ireland and Spain took off and as European banks expanded their operations in central and Eastern Europe.

What drove European banks to do this? By eliminating currency mismatch on banks’ balance sheets, the introduction of the euro enabled banks to draw deposits from surplus countries in their headlong expansion. Meanwhile, the permissive bank-capital rules under Basel II removed any regulatory constraints that stood in the way of the rapid expansion. To be fair, the permissive bank risk-management practices epitomised by Basel II were already widely practised within Europe before the formal introduction, as banks became more adept at circumventing the spirit of the initial 1988 Basel Capital Accord.

Compared to other dimensions of economic integration within the Eurozone, cross-border mergers in the European banking sector remained the exception rather than the rule. Herein lies one of the paradoxes of Eurozone integration. The introduction of the euro meant that “money” (i.e. bank liabilities) was free-flowing across borders, but the asset side remained stubbornly local and immobile. As bubbles were local but money was fluid, the European banking system was vulnerable to massive runs once banks started deleveraging.

Europe’s crisis: A banking crisis first, a sovereign-debt crisis second

The banking glut hypothesis is a better perspective on the current European financial crisis than the savings glut hypothesis. The crisis in Europe is a banking crisis first, and a sovereign-debt crisis second. It carries all the hallmarks of a classic “twin crisis” that combines a banking crisis with an asset-market decline that amplifies banking distress. In the emerging-market twin crises of the 1990s, the banking crisis was intertwined with a currency crisis. In the European crisis of 2011, the twin crisis combines a banking crisis with a sovereign-debt crisis, where the mark-to-market amplification of financial distress worsens the banking crisis.

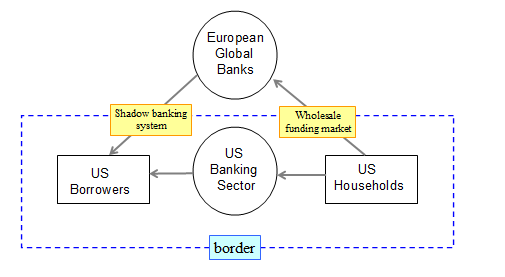

The banking glut in Europe was part of a global phenomenon, as documented in a recent paper delivered as this year’s Mundell-Fleming lecture at the IMF (Shin 2011). Effectively, European global banks sustained the “shadow banking system” in the US by drawing on dollar funding in the wholesale market to lend to US residents through the purchase of securitised claims on US borrowers, as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4. European banks in the US shadow banking system

Although European banks’ presence in the domestic US commercial banking sector is small, their impact on overall credit conditions looms much larger through the shadow banking system. The role of European global banks in determining US financial conditions highlights the importance of tracking gross capital flows in influencing credit conditions, as emphasised recently by Borio and Disyatat (2011). In Figure 4, the large gross flows driven by European banks net out, and are not reflected in the current account that tracks only the net flows.

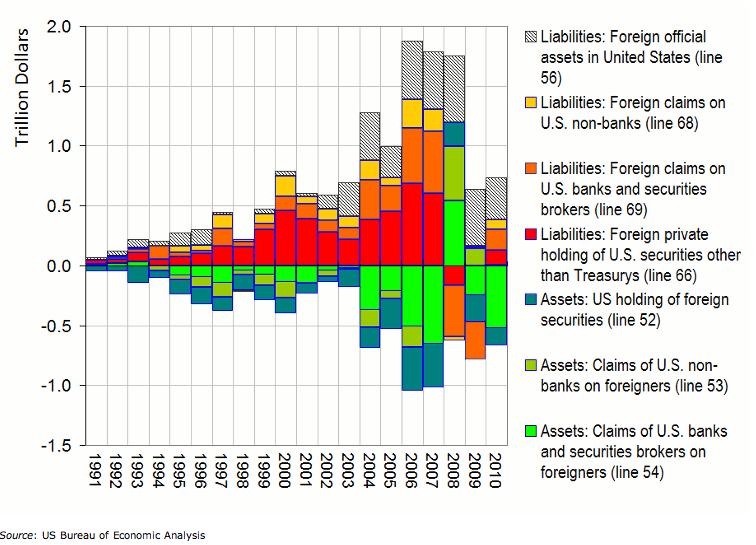

The netting of gross flows shows up in Figure 5, which plots US gross capital flows by category. While official gross flows from current-account surplus countries are large (grey bars), we see that private-sector gross flows are much larger.

Figure 5. Gross capital flows to/from the US

The downward-pointing bars before 2008 indicate large outflows of capital from the US through the banking sector, which then re-enter the US through the purchases of non-Treasury securities. The schematic in Figure 4 is useful to make sense of the gross flows. European banks’ US branches and subsidiaries drove the gross capital outflows through the banking sector by raising wholesale funding from US money-market funds and then shipping it to headquarters. Remember that foreign banks’ branches and subsidiaries in the US are treated as US banks in the balance of payments, as the balance-of-payments accounts are based on residence, not nationality.

European banks: Gross flows and US pre-crisis credit conditions

The gross capital flows into the US in the form of lending by European banks via the shadow banking system will have played a pivotal role in influencing credit conditions in the US in the run-up to the subprime crisis. However, since the Eurozone has a roughly balanced current account while the UK is actually a deficit country, their collective net capital flows vis-à-vis the US do not reflect the influence of their banks in setting overall credit conditions in the US.

The distinction between net and gross flows is a classic theme in international finance, but deserves renewed attention given the new patterns of international capital flows (see, e.g., Borio and Disyatat 2011). Focusing on the current account and the global savings glut obscures the role of gross capital flows and the global banking glut.

Net capital flows are of concern to policymakers, and rightly so. Persistent current-account imbalances hinder the rebalancing of global demand. Current-account imbalances also hold implications for the long-run sustainability of the net external asset position. For the US, however, the current account may be of limited use in gauging overall credit conditions. Rather than the global savings glut, a more plausible culprit for subprime lending in the US is the global banking glut.

As the European banking crisis deepens, the deleveraging of the European global banks will have far-reaching implications not only for the Eurozone, but also for credit supply conditions in the US and capital flows to the emerging economies. Just as the expansion stage of the global banking glut relaxed credit conditions in the US and elsewhere, its reversal will tighten US credit conditions. Its impact in the emerging economies (especially in emerging Europe) could be devastating. In this sense, there is a huge amount at stake in the successful resolution of the European crisis, not only for Europe but for the rest of the world.

This is very interesting, but I’m sure what I’m supposed to conclude here. How could/should this have been prevented and what is the best way of unraveling the mess? I’m none the wiser from this.

Reason,

“How could/should this have been prevented and what is the best way of unraveling the mess?”

This is just the old problem of balancing supply and demand.

Humanity has been taught that an individual’s excess production today can somehow be “saved”. This confusion is the source of the imbalance and source of runaway greed.

All anyone gets in return for exchanging one excess production (savings) is a claim (an equity claim or a debt claim). Understood this way money becomes a “social relationship”.

A good thing about an equity claim is that it is self-adjusting. One loaf of bread invested may return zero or many loaves of bread in the future depending how the “social relationship” constructed by the claim pans out.

A debt claim (like bonds, treasurys, fiat currency) is not self-adjusting. That is why debt based currency is a disaster. In a debt based system there is an expectation that one loaf of bread saved should return one loaf of bread in the future. This is the lie of modern banking. This lie is what gets us into trouble.

mansoor h. khan

Those seeking to understand all this should pick up a little book called The Death of Money, written in 1993 by someone whose name escapes me. Even back then the world was awash in financial flows which drawfed the “real economy”. Those who understood this and were properly positioned in powerful institutions have been literally making money out of thin air since at least 1987, when Greenspan turned on the tap at the Fed in the aftermath of that year’s market crash. As Karl Marx might have said (and some guy at Goldman or the Harvard Business School probably did say) ‘it no longer really makes sense to make things when it is now so easy simply to make money.’ The other side of the money these insider tycoons have been making is today’s mountain of debt: soverign debt, municipal debt, mortgage debt, student debt, credit card debt. All this debt serves as collateral enabling creation of further debt and trading profits (bubble phase), until the creditors start getting nervous about collateral values and begin increasing haircuts, causing the debt to implode and producing crashes like the one we may be experiencing the beginning of right now.

see:

The death of money : how the electronic economy has destabilized the world’s markets and created financial chaos / Joel Kurtzman. Published/Created: New York, N.Y. : Simon & Schuster, c1993.

LCCN permalink : http://lccn.loc.gov/92037530

1993?

Has he (is he) updated (updating) it?

Jake Chase Said;

“Those seeking to understand all this should pick up a little book called The Death of Money, written in 1993 by someone whose name escapes me.’

Those of us (the Neo’s and Trinity’s) who see the matrix for what it is need to start evangelizing / prosletyzing the masses.

Only enlightenend masses can put an end to bullshit.

mansoor h. khan

Don’t disagree, that is why I think the MMT people have a point.

But I do disagree with them on some specifics and on their emphasis. In particular, I don’t agree with employer of last resort (I think it is impractical), I don’t agree with indifference to trade deficits (they represent a dangerous flow of ownership) and I don’t think it is always possible to switch taxation on and off like a tap.

I think we need a few simple adjustments:

1. Limited liability means strictly limited leverage – if you want to gamble – do it with your own money;

2. We need looser fiscal policy (i.e. more base money) and tighter monetary policy (i.e. less debt money) – the opposite of the mix that has been in vogue;

3. We need some active policy to avoid chronic balance of payments imbalances – from both debtor and creditor countries. Comparitive advantage only works as a model if currency prices maintain approximate trade balance.

P.S.

(On a more micro level, I prefer a tax mix including more VAT – which taxes imports but not exports – to one with more income/payroll taxes which tax exports but not imports – but that needs to be augmented with some sort of wealth tax (e.g. inheritance taxes, land value taxes). And I want what I like to call a “national dividend” – you might call it a citizen’s income – that could replace lots of social insurance with a simpler system + the advantage that it is one massive automatic stabilizer.)

Note:

While I don’t think it is so easy to change taxes, I do think that bond sales vs monetarisation of debt could be used as an effective way to macro-tune the economy ala MMT.

reason said,

“2. We need looser fiscal policy (i.e. more base money) and tighter monetary policy (i.e. less debt money) – the opposite of the mix that has been in vogue”

Why do we need any debt money? Just remove deposit insurance and lender of last resort protections and watch the goons (the banks) die. Let the gov provide a safe risk-free deposit account and check clearing services.

Please also consider a more decentralized way of thinking about MMT. If impediments to local, state and private currency issuance are removed then the central gov (FED MMT) may not need to as much to balance supply and demand. It can be done at the local,state and private levels (i.e., payment of labor via common stock issuance by corporations).

mansoor h. khan

So you want no more consumer credit? Young people who want a job where they have to drive to work, have to hire a car? Young people wanting an overseas holiday have to wait a year or two (and quit mit career)? Houses can only be bought on shared equity deals? Family firms always have to go public if they want to expand?

Credit has its uses.

Andy Lewis,

why do think there is so much to do about “shovel ready” projects. And what projects could effectively use and manage the complex and varied skills and capabilities of the workforce in a modern economy. Think seriously about how you practically go about it. Then imagine the disruption as people keep leaving for better paid private jobs and new ones keep arriving. I think a basic income subsidy works better for everyone and costs fewer real resources.

“Please also consider a more decentralized way of thinking about MMT. If impediments to local, state and private currency issuance are removed then the central gov (FED MMT) may not need to as much to balance supply and demand. It can be done at the local,state and private levels (i.e., payment of labor via common stock issuance by corporations).”

Why make things more complicated when we can make things simpler?

P.S.

Actually, I think a shared equity scheme for mortgage finance WOULD be a good idea. And maybe other finance should be term limited – all debts should be repaid within a certain time or default (of course that might just mean rolling finance)!

Reason said,

“Credit has its uses.”

Ok. I don’t want any credit money issuance. But that does not mean that money issued by gov cannot be borrowed. Granted interest rate will be much higher but we won’t have to deal with “peak credit” and deflation as much.

And remember, credit money issuance means that any money issued via credit means less money gov can issue for social spending and citizen’s dividend.

Credit money is not magic. It is still using the society’s economic capacity. Inflation still matters and much be watched.

mansoor h. khan

reason said,

“Why make things more complicated when we can make things simpler?”

Because if there are two ways of managing a process (one centralized and one decentralize) where the centralized method does not have a big advantage over the decentralized method then decentralized method is better.

Because decentralized method will cause less damage if abuse, fraud and mis-management takes place. Also, decentralized method will mean more responsiveness to the local needs and probably more creativity and more ways of doings things and more ownership and more participation and satisfaction at the locals.

mansoor h. khan

“Because if there are two ways of managing a process (one centralized and one decentralize) where the centralized method does not have a big advantage over the decentralized method then decentralized method is better.”

But complexity IS always a disadvantage (and increases cost) – why do you think so many things have been centralised in the first place? I understand that there is a tradeoff between innovation, flexibility and diversity on the one hand (provided by decentralised decision making) and control and efficiency on the other (centralised decision making). This applies not just to government – every large business faces the same trade off and tends to go through cycles of one or the other.

reason said per mansoor said;

“centralized method does not have a big advantage over the decentralized method”

I think we agree more than disagree. Yes, if there is a big advantage to centralizing it should be done. Also, centralization shoud not be forced on a populace. There should be popular support. Doing justice is more important than doing efficiency only.

mansoor h. khan

“I don’t agree with employer of last resort (I think it is impractical)”

Been done successfully from the time of the Pharoahs through to FDR.

It’s extremely practical.

Agree with you that trade deficits are something which one must watch carefully, but the problems there are mostly due to the relocation of factories (which have real value).

“Humanity has been taught that an individual’s excess production today can somehow be “saved”. This confusion is the source of the imbalance and source of runaway greed.

All anyone gets in return for exchanging one excess production (savings) is a claim (an equity claim or a debt claim). Understood this way money becomes a “social relationship”.

In general, I agree. That is a common misunderstanding.

Gold bugs in particular make this mistake.

I started learning about economics and finance from scratch in about 2009, and having only common sense for preconceived notions, non self-adjusting debt made (makes) no sense. If a house value drops, shouldn’t the value of its mortgage drop too? Why do consumers get the short end of the stick while the banks’ only risk is that the consumer might foreclose? No wonder everyone is screwed.

Oren,

” Why do consumers get the short end of the stick while the banks’ only risk is that the consumer might foreclose? No wonder everyone is screwed.”

Now you get the point of the biblical and quaranic prohibition against usury (interest based economic system).

The bible and the quran predict as the future (already known to the creator) unfolds the scripture will be validated.

mansoor h. khan

This sounds like the money version of situational ethics, I.E. nothing is absolute.

If one borrows $100 to buy a house then that is what they owe, if the situation changes such that the house could be bought for $90 they still owe $100.

mac said,

“This sounds like the money version of situational ethics, I.E. nothing is absolute.”

Please expand your thinking. Under equity based financing I would not be able to get a mortgage easily (at least the interest rate would be much, much higher).

So what is the alternative. Well. In this situation a I would rent. But how would the landlord be financed?

The landlord can be financed via stock sale just like corporations do today and I would be able to buy the landlord’s stock. The pooling would have to take place via money first being issued by gov into the economy (gov spending or social dividend). The equity raised via stock sale is the pooling of money.

Therefore, i would have to wait a lot longer to buy a home outright (because I would have to accumulate the money) but I can still get benefit of appreciation by buying stock in my landlord’s company until then.

mansoor h. khan

“Net capital flows are of concern to policymakers, and rightly so. Persistent current-account imbalances hinder the rebalancing of global demand. ”

I’m of the view that persistent current-account imbalances (i.e. undervalued currencies) result in very low nominal returns on domestic real productive investment – leading eventually to a liquidity trap. I don’t have a formal proof of this but it seems intuitively right to me – nearly all domestic industries struggle with foreign competition. Low returns on domestic real productive investment leads eventually to a preponderance of leveraged speculative bubbles as investors look desperately for increased returns.

Classically this situation should be resolved simply via capital flows OUT of the country leading to devaluation. But the opposite has happened (pointing out a huge problem in the classical model).

I don’t have time to write an explanation of why you might want to do so currently (might do so tonight, if i can find it), but I’d recommend you pick up David Harvey’s book The Enigma of Capital. The explanation he gives there suggests you’ve got the precise nature of the relationship wrong, but I’d agree that there definitely is one (bigger pension funds+more wealth investors -> more money looking for RoI, but more capital floating around, so fewer opportunities to invest -> low average RoI on investment. As such, the problem is not that of the savings glut in Bernanke’s sense, but rather in the sense that the low yields on traditional investments leading to too little return for too many, causing them to invest in ways that are riskier, such as asset bubbles. Financialization compounds this issue.)

Foppe,

but I thought that the evidence was that in fact global savings rates (as a function of income) have not been unusual. Why should ROI be unusually low, unless it has to do with misaligned prices (in this case exchange rates) and misaligned capital flows (capital flows should equalise ROI – no?)?

Because the total amount of saved money is too high compared to the amount of money needed for all healthy growth opportunities. As a result, the yields on the total amount of savings that *could* be invested are very low (even though in practice it will turn out that a lot of savings generate no ‘yield’ at all, while relatively few players manage to get all of the really profitable investments). This encourages people who cannot invest in any ‘safe’ investments to turn elsewhere for RoI, thus causing asset bubbles to inflate. (What the banks do is somewhat different.)

One example that illustrates this problem well is the following: back in the mid-1990s many Western pension funds were generation very low yields, because of the fact that the mostly-mature western economies needed fairly little of that money for new investment. This caused lots of hand-wringing at the time, and people and regulators started to look for ways to increase those yields. They “solved” it by allowing/forcing those funds to put money into the stock markets (dotcom), and by letting them buy AAA-rated OECD sovereign debt. Great idea, non?

“Because the total amount of saved money is too high compared to the amount of money needed for all healthy growth opportunities.”

Your because ignores my empirical point, and so simply side-steps the question. I’m not sure that this in general is true.

“One example that illustrates this problem well is the following: back in the mid-1990s many Western pension funds were generation very low yields, because of the fact that the mostly-mature western economies needed fairly little of that money for new investment.”

If that was the case why weren’t they investing (even if indirectly) in growing economies then – pushing down the exchange rate and making local industries at the same time more competitive and profitable?

It’s not a side-step. Compound growth forces the total volume of money accumulated to grow ever larger even while the %age saved remains the same. The fact that the savings rate doesn’t change doesn’t change the fact that the growth of the money supply cannot be matched by the growth in real-world development.

Actually,

I thought more about this overnight and also came to the conclusion you were pointing slightly in the wrong direction. The problem is the increase in leverage, not basic savings (the compounding is irrelevant – that is income and so would be included in the savings rate calculation). The increase in leverage bids up the price of financial assets (and here I include land as well as equities and bonds) and so reduces the yield. If we limit leverage, this process can’t happen.

But you are still ignoring that (more) balanced trade would tend to equalise ROI.

…but rather in the sense that the low yields on traditional investments leading to too little return for too many, causing them to invest in ways that are riskier, such as asset bubbles. Foppe

Asset bubbles are typically inflated with credit, no? And credit creation bypasses the need for the population’s savings and thus the need to pay honest interest rates, true? And if the population has been cheated out of honest interest rates then how can it be expected to buy the new production from the new investment?

You’ll notice that I was describing one rendition of the developments of the past 30 years, rather than making a normative statement. ;)

Actually, I understated the problem. If savers receive negative real interest rates then their ability to consume will be reduced by investment rather than increased!

bigger pension funds+more wealth investors -> more money looking for ROI

You’ve left out the point of the article, that shadow banking companies with fiat bogus money were competing with people’s real money. They not only were at the scene of the crime, they were the doers. They were not innocent bystanders watching in horror but helpless to do anything.

That is, if the savings from a lifetime’s labor can be equaled out by a trader’s push of a button, it devalues labor. If wealthy investors put up the family fortune, someone, somewhere actually was part of real economic activity. If the constraint of real economic activity is gone, so is any sense of reality. If a few slicks can gin up the system with balance sheet entries, the ink will flow and the blood will spill. Financialization doesn’t compound the issue, it is the issue. Velocity is a bad version of the multiplier effect and should be taken out of the equation.

The various bubbles of the last ten (thirty?) years have been created with virtual money and paid for with real money. To respond to reader Reason, just take fiat powers away from private banks and near-banks and groups who say they’ve been in a bank, and give it to governments. Deprivatize the mint. And a few bankers in prison wouldn’t hurt, either.

A. I don’t understand this. Even shadow banking institutions need to use the regulated banking system’s clearing system. (i.e. They need to borrow money from the regulated banking system to create a loan.) How can this be otherwise?

B. I don’t care anyway if it is the shadow banking system or the real banking system creating the extra leverage, the problem is the extra leverage.

C. Yes there was clearly fraud, and people should have been prosecuted.

Short-term rates remained low because the Fed didn’t raise them as long as inflation didn’t appear to be an issue (25, 27).

Because the Chinese were parking their export earnings in risk-free US Treasuries instead of buying more US products? That’s easily fixed. The US Government, being monetarily sovereign, should never borrow in the first place. And if the problem was Chinese lending to US banks that could be discouraged by abolishing government deposit insurance and a lender of last resort.

“And if the problem was Chinese lending to US banks that could be discouraged by abolishing government deposit insurance and a lender of last resort.”

Talk about collateral damage! WOW!

Why not just limit deposit insurance to domestic depositors?

Why not just limit deposit insurance to domestic depositors? reason

Before the abolition of government deposit insurance, the US Government should provide a risk-free storage and transaction service for its fiat that pays no interest and makes no loans.

To anyone: Something that isn’t clear to me: to what extent does the savings glut meme depend for its coherence on the idea that banks lend out reserves? It seems to me that if you recognize that banks aren’t constrained in any way, then how much sense does this still make?

I think they still need a fig leaf. The history of fiat money from destitute institutions (governments at war, cattle companies with dead cows, mining companies who can’t stock the company store, etc.) shows that faith is a big part of the equation.

Even if two weasels, er, financial professionals, were doing some prop trading with what they knew to be worthless money, they still need the assurance that the winner could spend the excess as if it were real. Otherwise, it would be a purely academic exercise.

‘So what caused the crisis? Clearly, the shadow banking system (mainly based around US and European financial institutions) succeeding in generating huge amounts of leverage and financing all by itself.’

Yes. And the roots of every bust are found in the bubble that preceeded it.

In the 1990s, shadow bankers made TONS of money on the European sovereign convergence trade: buy peripheral sovereigns, short bunds, and collect millions as the interest rate spread shrank like an ice cream cone in the Mediterranean sun! Thanks to the wonderful marginability of sovereign debt (north of 90%), this profitable one-way trade could be put on with immense leverage.

As the convergence trade ended a decade ago, traditional banks stood ready to take over those sovereign bonds from shadow-bank speculators. Why? Because under Basel II, government bonds require no risk weighting. Even though sovereign credit risk was not a concern then, the Basel II rule was still obviously wrong: the extreme turbulence of the early Eighties proved that sovereign bonds are certainly subject to interest rate risk in higher maturities. Thus, they SHOULD be risk-rated in line with their duration.

Finally — a point made yesterday by ECB governor Draghi — peripheral governments became convinced that they were ENTITLED to borrow at narrow spreads. Like U.S. punters buying Vegas condos with nothing down, peripheral eurozone governments became convinced that they were sound, prudent borrowers simply because lenders showered them with nearly-free money. Draghi pointed out that owing to structural rigidities, some of them exhibited no real growth for a decade, even as they bulked up their borrowing.

Now every element of this virtuous circle has turned vicious. Banks, flush with sovereigns thanks to the distorted incentives of Basel II, are bleeding as spreads widen and prices sink.

Yesterday, Draghi asserted that while pre-crisis spreads had undershot, now they have overshot. We’ll see about that. Effectively, he is betting his career on this view.

I claim that not only will Greece default next year, but also it will be forced soon afterward to leave the eurozone. Portugal likely will follow Greece in short order. At that point, a free-for-all ensues, in which Germany may be tempted in self-protection to re-establish the D-mark.

Draghi strikes one as a perceptive man who has hitched his wagon to a broken monetary system that can’t be saved. He is thus a tragic figure of our age. A cynic could say that the French, prime movers in creating the euro, have handed the ECB baton to an Italian captain just in time for him to go down with the ship. Quel dommage, mes confrères!

NEVER THE TWAIN SHOULD MEET

No – one must go further back, I submit.

The crisis was caused by the ability of Investment Banks merged with Commercial Banks to assimilate within their capital reserve positions the assets of the latter. Incredibly, this means that commercial bank accounts (read “my money” and yours) was assumed as a collateral reserve offset (guaranteed by FDIC up to $250K) for speculation by their Investment Banking departments.

The FDIC was established by the same legislation (the Glass-Steagal Act) that separated the two types of banking operations employing common sense. Meaning that Commercial Banking are a risk-averse business whilst Investment Banking is a risk-prone business – and never the twain should meet.

So, I humbly suggest, it does not really matter what instruments were employed to cover their speculative bets, those bets should never have been made in the first place because they were placed with funds that did not belong to the Investment Banks.

During the Credit Mechanism Seizure in the fall of 2008, Commercial Banks were considered highly bankrupt-able because of the speculative operations of their Investment Banksters. The combined debts were superior to the combined assets – so, without government funding to save their sorry backsides, failure was inevitable.

Meaning this: The banks were thus TBTF because they were holding Our Money – and to fail would have wiped out those savings on deposit with them. Which was considered, and rightly so, as unacceptable.

[That is, we would have got this email from our bank, “It is with deep regret that we must inform you of our declaration of Chapter 11 bankruptcy, the consequence of which must be that we are obliged immediately to cancel your current account and disable your credit-card facility”.]

MY POINT

Once again, we challenged the wisdom obtained from past experience as “historically flawed” because, it was argued, that “today is different from then”. Subliminally, this meant that, whether the argument was false or not, it suited conventional wisdom by which nothing must hinder a banker from doing profitable business. And certainly not either common sense or wisdom.

The belief-of-the-day was the supercilious nonsense that markets were self-correcting. In fact, as the markets did indeed demonstrate, they may self-correct to null-values if left to do so.

POST SCRIPTUM

George Santayana: “Those who refuse to learn the lessons of history are condemned to repeat them.”

Lafayette: “And repeat them again and again and again.”

and the lesson learned by banks, oligarchs and now hedge funds from history is—it’s all good, never a downside, can always short, manipulate, defraud, re-write the law and if all else fails there is always the deep pockets of the suckers….eerr uuhh…I mean the taxpayers for a bail out—again and again and again.

Finally, someone who mentions the wee issue of pervasive criminality and extortion.

Across the blogosphere criminality has been repeated incessantly to a point of almost being boring.

Enough of the victimization. Now’s the time we DO something about it instead of bitching-in-a-blog.

What do you suggest? I hope NY AG Schneiderman will do something.

But when SEC, AG, and judges are corrupt, as we have found at the federal level, it becomes a difficult question how to punish criminality. Guillotines are not readily available in the market these days. ;-)

I can never figure out what the FED means to begin with – on the one hand there is a “savings glut.”

On the other hand, the banks don’t have enough reserves, or capital, or whatever you want to call it (???money???)

So which is it?

“Keep in mind that this is not a mere aesthetic argument. If you believe the Bernanke argument, you’ll argue that China needs to let the renminbi appreciate faster and provide more safety nets to its populace so they can shop almost as much as Americans do. If you accept the Borio/Disystat analysis, it means you need to regulate financial players and markets far more aggressively.”

Bernanke – regulate banks aggessively??? OW!!! I hurt myself laughing….

The global savings glut is a euphemism not to be taken literally. It was spare change looking for returns, globally. Garet Garrett explains the situation in The Bubble when discussing Morrow’s observation and article “Who is buying foreign bonds” Investment banks were creating foreign loans and marketing them to little people in the US, like farmers as investments. The farmers would know nothing of risk. This time the loans originated in US housing and were sold to the little people and some big ones globally as money good with high ROI, for a while. These buyers were insensitive to the rates set by the Fed. They wanted the product.

If you look at who got the TARP money from the Treasury, and the crypto-TARP money from the Fed, you’ll see it wasn’t ‘the little people’. And I do not recall farmers and blue collar workers crying out for product.

Are prop trading desks ‘the little people’? Dunno, dunno.

However it is ‘compli-fi- cated’ by arcane language, the scheme and structures “enriched employees” at the expense of shareowners and nation states. That is the objective of the entire scheme and structure. The solution is to prosecute the schemers and clawback the proceeds from their cold, dead hands. It not only brings some measure of justice but deters future schemers.

The fact that mainstream economists and government officials want to argue about something besides the nature of the game’s reality which is “enriching employees at the expense of owners and nation states” just means that they expect to benefit from the game and are engaged in the game or were engaged/benefited from the game.

Strange absence of any reference to either crime or legalized crime.

All hope is not lost. Just motivate international bankers to start travelling again. Then everything will be fine (as described in the tale below).

http://klauskastner.blogspot.com/2011/12/how-greece-could-build-up-so-much.html

It will be interesting to see/read/hear what the Planet Money crew have to say about this paper. They promulgated this Savings Glut concept to many public radio listeners.

Funny blurb on Max Keiser. It now costs more in Alabama for sewer and water service than for foodstamps. Deflationesque. (Why don’t we acknowledge our HUGE environmental deficit – we could use it about now to balance our fairydust books.)

How can oil exporters store their wealth in financial instruments and expect to call on them later when they have less oil and lots of currency? By that time the commodities of value will be wheat and water and no one will part with either, regardless of how much colored paper you wave in front of their faces.

Good question. I note the US decided to put of lock on oil resources from Libya to Iran some time back.

The “savings glut” explanation always struck me as a kind of technically almost-correct spin. Technically correct because S>I, and since “says law” is rubbish, we know there is no reason for I to increase to restore balance. In fact, S being high really means C is low, and then you end up with unintended I in the form of rising inventories. And so output and income adjusts downward, etc.

I guess we can give them a half point for not invoking “says law”, but it still seems it would be much clearer to identify the problem as a lack of demand (a lack of both consumption and investment). What is going on rhetorically though seems to be that they want to blame China and others overseas, so as to ignore acknowledging the culpability of the Fed.

There’s a small nugget of truth there as well. China has been using it’s excess dollars to buy US Treasuries, rather than convert back to Chinese Yuan, in order to keep foreign exchange markets from adjusting. And, they themselves restrict foreign capital inflows and won’t allow the Fed to correct the problem by in turn buying Chinese Yuan.

But it’s not as though this has left the Fed helpless. The obvious move, if you need to discourage foreign inflows, both from foreign central banks and from foreign shadow banks, is to allow a little more domestic wage inflation. We know that with free capital flows and a floating currency, domestic price levels should directly impact exchange rates and foreign capital flows. Yet it is unmistakable that Fed policy was exceptionally tight throughout this period, with Fed tightening at the first sign of rising wages being the most proximate cause of each of the last 3 US recessions.

And it’s not only the Fed; such limp monetary policy seems to have been a trend with global consequences. Whether you call it a “savings glut” or a “liquidity trap” doesn’t make a big difference, what we have now is the predictable consequence of the global war on wages. Yes, at this point, spending will be essential to produce the needed adjustment. And if you could somehow induce lower private sector savings, that would increase private sector spending. But it is unclear how policy can accomplish that, aside from taking the more direct approach of simply increasing government spending.

Still, better monetary management might have helped to prevent much of this mess in the first place (and better regulation would have prevented the rest). Politically though, I imagine it seems easier to some to blame China then to call for the needed levels of spending. So we’ll be hearing more of the “savings glut” argument despite the evidence.

“Yet it is unmistakable that Fed policy was exceptionally tight throughout this period, with Fed tightening at the first sign of rising wages being the most proximate cause of each of the last 3 US recessions.”

Exceptionally tight? Which period? Compared to what?

I grant that destroying wages and replacing them with debt is a major cause of this huge credit bubble over the course of decades, but the notion the Fed targeted suppression of wage inflation this last time and kept policy too tight while the biggest bust ever was in sight is a bit of a stretch. Surely it’s easier to see wage suppression as the result of factors including private sector unions destroyed, acceptance of the whole idea of a mass-consumption-of-goods, low-wage “service” economy, and intense (and unbelievably destructive) globalization of capital and global supply lines.

“Compared to other dimensions of economic integration within the Eurozone, cross-border mergers in the European banking sector remained the exception rather than the rule. Herein lies one of the paradoxes of Eurozone integration. The introduction of the euro meant that “money” (i.e. bank liabilities) was free-flowing across borders, but the asset side remained stubbornly local and immobile. As bubbles were local but money was fluid, the European banking system was vulnerable to massive runs once banks started deleveraging.”

This is backwards; deposits are liabilities and loans are assets in bank accounting.

I’m puzzled bu all of the foregoing. I thopught it to be obvious: we have a crddit money glut, that is, we owe far more than we can service. A savings glut would make is very easy to cure our current distress; use the excess savings to pay down the excess borrowing. But; we can’t do that becasue we don’t have enough unencumbered money to pay down the debt immediately, we have to string it out while at the same tiume we consume less than we had been consuming.

I have a bone to pick with this post, it spends too much time with a topic that is at it’s core very straight forward. One can get caught in the minutia and miss the point. Savings Glut . . . Bullshit. Excess debt, Indeed!!!

Who do you think “we” owe that money to then? Clearly someone had to have excess savings in order to lend it out in the first place.

I think the rich right now still have plenty of unencumbered money, the problem is “we” just haven’t been willing to tax it at historical rates.

I honestly didn’t think anyone believed Bernanke’s saving glut defense even at the time it was made. Back then we talked about the paper economy and not wealth inequality and kleptocracy but either way both were about wealth transfers upward and the privileging of investment income, later we took to calling this rents, over labor income. Much of this came out of the Fed policy since the 70s of attacking workers’ wages as inherently inflationary while facilitating investment bubbles. This trend was accentuated by government led destruction of unions, thereby weakening workers’ power to seek wage gains and by tax cuts from which the rich primarily benefited. This last was called variously trickle-down, supply side, and more accurately voodoo economics (that was I believe Bush I’s line in the primaries before he became Reagan’s VP choice, at which point he got religion, more precisely voodoo religion).

At any rate the resultant wealth transfers have had the dual effect of hollowing out the American middle class, which is the consumer base of the country while at the same time, and as others have noted here, pushing the paper economy into to seek greater profits in the face of fewer or less profitable investment opportunities. This has created the cat chasing its tail spiral of leverage building on itself on a paper on paper binge but also pressure on the real economy to offshore and outsource in the belief that this will maximize their profits –with the result that the strain on American workers/consumers only increases, forcing them further and further into debt, which then allows even greater rents to be extracted from them in the form of fees and interest on debt.

“I honestly didn’t think anyone believed Bernanke’s saving glut defense even at the time it was made.”

No kidding. It apparently escaped his notice that US-based multinationals and hot money handlers were falling all over themselves plowing into China for immense profits.

Hokay I tend toward the glut/great-pool-of-money re the naughties.

YS: “shorthand for the Chinese are to blame” Not in my thang.

In my thang, the Chinese are about creating the nation’s ability to determine its destiny. The West wrt China is about “better in the tent pissing out.” Thus WTO membership w/o obligation to float currency.

In my thang, Chinese accumulation of sovereign credits is played against accumulation of Western tech, the goal being not quarterly profits but the ability of the nation to determine its destiny.

Way simplistic view, but apply it on decade scale and to specific arenas like industrial espionage. (& compare to self-destructive US initiatives such as SOPA.)

YS: “average global savings rate over the last 24 years” OK but don’t we need to get down in the weeds a wee bit more?

Hyun Song Shin: “According to the ‘global savings glut’ hypothesis, Chinese savers favour US Treasuries because China lacks deep financial markets that could cater to demands for safe assets…”

This talk of Chinese “savers” makes it seem that the accumulation of US sovereign credits was made by other than CCP functionaries. WTF???

Most likely I need to go back and read it again, but to deny that China’s demand for AAA USD credit was a major factor in causing weirdness in that market seems a stretch.

It strikes me that a lot of people still (even after that stimulating series by Andrew Dittmer) very much utopians. They want to radically reorganise the world, rather than making incremental changes that might make a big difference. Don’t humans ever learn?

The human race has been on a very clearly manifest (even in corners of the popular consciousness) trajectory towards calamity since the ’60’s, and every incremental move since has been in the wrong direction. We’ve made an utter hash of it, are in dire peril and deep denial re our prospects. We are the idiot savants of the animal kingdom. Clock is ticking.

Agree with some others’ comments, but would like to add:

This struck me as odd in that somehow China disappeared as the “villain” (always absurd, in my view) only to be replaced by the “European banking system” or some similar expression to identify the culprit. The US financial elite, private and regulatory, is portrayed as dull-witted, or provincial, or peripheral, or at most, junior co-fool, rather than at the heart of financial(and every other) power on the planet.

And of course, the word “criminal” or “fraud” or at least “corruption” is completely missing, yet we know without the slightest doubt that none of this could happen without endemic moral, financial and legal bankruptcy.

But I have another question:

Let’s suppose everything in the piece is correct so far as flows are concerned. This is the end of 2011. The crisis broke in summer ’07. So let’s say it took 4 years to correctly analyze and sort through the problem, and authorities are now ready to act.

However, nothing has been done to actually fix any of it in the intervening span, everyone paying attention knew the crisis isn’t only not over, but the speed of the events we are attempting to understand keeps accelerating. A smallish global collection of truly base character has had all that time to prepare who knows how many scenarios that leave them with egg and us with the shell. How far behind are we in our understanding of what’s really going on right now that has already perhaps determined the outcome? We need to slow the whole thing down – I suggest some serious charges for starters.

At the moment, we’d be best served if all the executives of every major bank went on the same cruise ship, and it sank. Call it “The Titanic”.

That might help. At the moment they seem to be too powerful to be prosecuted for their crimes, though I’m hoping NY AG Schneiderman proves me wrong.