John Giddens, the bankruptcy trustee in MF Global, garnered headlines Monday by saying that he will decide in the next 60 days whether to filing suits against Jon Corzine and other officers for breach of fiduciary duty and negligence and against JP Morgan if he is unable to come to a settlement. JP Morgan so far has returned roughly $518 million in MF Global assets and $89 million in customer monies, a meager recovery relative to $1.6 billion in missing customer funds.

The report Giddens released Monday is thorough and confirms many of the observations made in journalistic accounts of the firm’s collapse, particularly regarding inadequate risk and accounting controls, JP Morgan’s aggressive posture greatly increasing the liquidity squeeze. It also makes clear that this is an interim report, and unlike the trustee’s report on Lehman, says that reaches no conclusion regarding legal strategies, including whether prosecutions are warranted.

But a stunning revelation that comes early in the account and is central to the failure of the firm does not get the emphasis that it warrants.

What is not surprising but nevertheless important is the way the document depicts MF Global as a train wreck waiting to happen. Ironically, the firm is a casualty of ZIRP. MF Global historically had gotten most of its income from low risk activities, such as interest on customer margin. Its net interest income from those sources fell by $3.5 billion from 2007 to 2011. Corzine had embarked on a strategy of turning the firm into a full service investment bank, an approach we deemed doomed to fail. To get there, Corzine took an approach that was similar to the one of Lehman and Bear, who were vastly less behind the industry leaders than MF Global was: putting lots of their chips in high risk, high profit potential activities (for Bear and Lehman, real estate; for MF Global, prop trading, specifically, Corzine’s Eurobond trade) in the hope that they could grow more rapidly than the top firms and thus close the gap with them.

But if you are going to increase firm-wide risk in a big way, particularly in a trading firm, it is critical to have solid risk and financial controls, and MF Global’s internal audit had reported considerable shortcomings on this front in 2010 and 2011. Yet Corzine went gung ho for growth without having those in place; indeed, as was recounted in the media and in the report, the chief risk officer, Michael Roseman, was evidently forced out for daring to tell the board he was concerned about the magnitude of the Corzine’s Eurozone bets and made sure his successor was less influential. Giddens criticizes MF Global management for both increasing trading risk and entering into new lines of business without making the needed investments improving Treasury processes, trade reporting, and liquidity management.

Not surprisingly, the firm was under stress considerably before the crisis hit. Even though Corzine’s approach improved the firm’s results, it was still losing money. And the rating agencies didn’t simply want MF Global to be profitable; they required the company to earn $200 million pretax to keep an investment grade rating (being downgraded would and did produce a death spiral, since counterparties would demand higher collateral postings from an already-liquidity-strained and highly levered firm). So the firm was running out of runway and was not even close to achieving takeoff speed.

The report recounts how the firm was coming apart before the denouement, which was triggered by Finra determining that the firm was capital deficient and demanding an infusion of $183 million, which the ratings agencies ignored until a Wall Street Journal story six weeks later, on October 17, forced them to take action. Employees were unclear as to whether some of the increasingly aggressive ways they were using funds in customer accounts were permissible. And the money shuffling was reaching a scale and complexity that even if it wasn’t pushing the envelope, a screw-up was likely. From the report:

During the summer of 2011, some senior executives appear to have been in deliberate denial of the extent of the liquidity stresses. Most strikingly, on August 11, in an email exchange between Ms. O’Brien and a Global Treasury employee at MF Global Hong Kong, Ms. O’Brien wrote that “Henri [Steenkamp] says to me today . . . ‘we have plenty of cash.’ I was rendered speechless and wanted to say ‘Really, then why is it I need to spend hours every day shuffling cash and loans from entity to entity?’”, a process that she described as a “shell game.”

Stenkamp was the CFO. The fact that he was telling employees, and perhaps investors, that the firm was well funded when it wasn’t, at best shows how poor management controls and information were. (Another issue flagged by the report is that there had been a good deal of turnover in Treasury and related functions. This made a bad situation worse, since seasoned employees were compensating for gaps in formal reports by communicating with each other via e-mails and journal entries). Note this is consistent with the argument made before on this blog, that MF Global is a prime candidate for litigation, potentially prosecution, for Sarbanes Oxley violations, namely false certifications about the adequacy of internal controls.

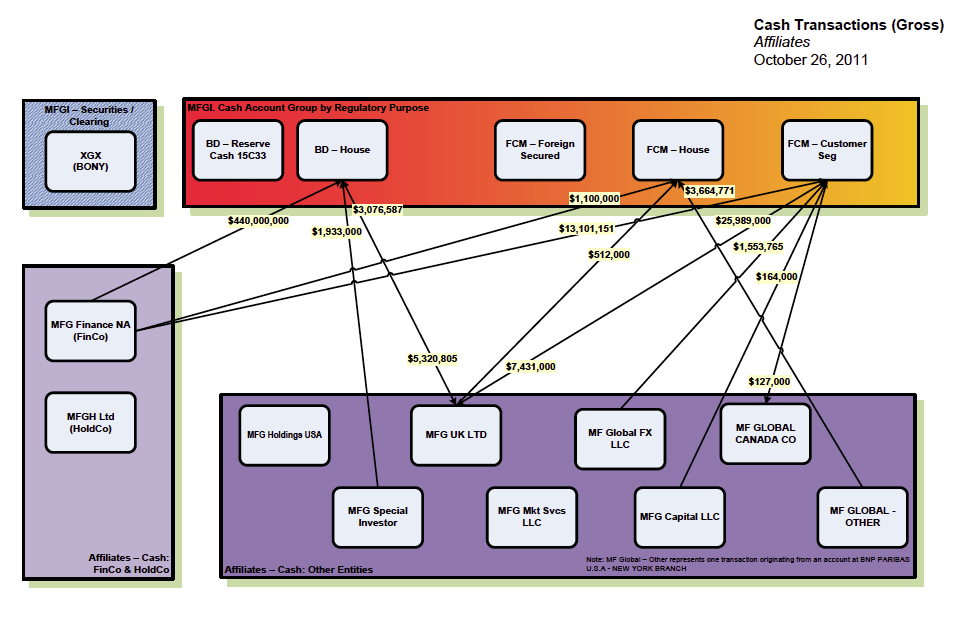

The report includes 53 (!) pages of charts in the report which attempts to track this cash and loan shuffling in the final days:

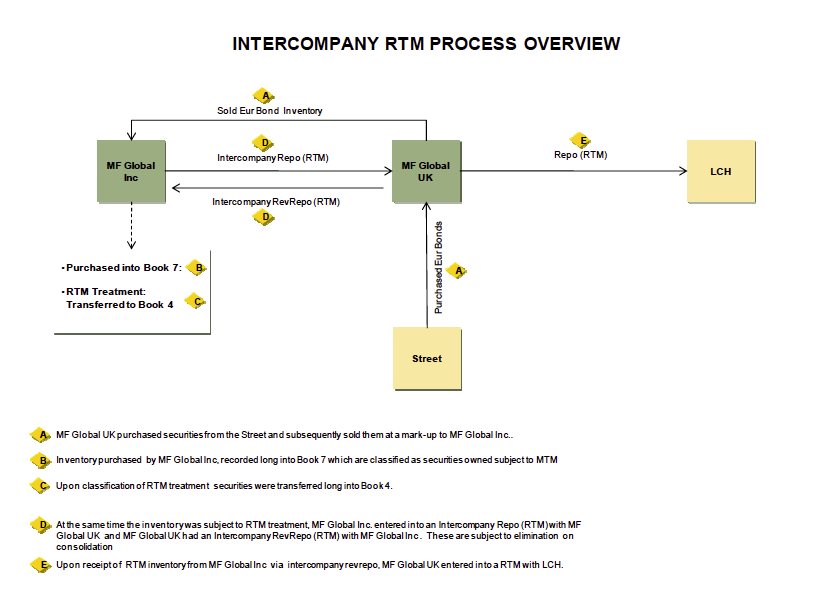

But the real stunner comes early in the report, and the media write ups thus far seem to have missed it completely. Recall that the trade that felled MF Global was one directed by Corzine, and has been depicted as a repo-to-maturity trade, in which the maturity of the repo matched that of the underlying asset exactly. That in turn allowed the trade to be treated as off balance sheet, which was helpful in presenting the firm’s results to ratings agencies and analysts.

The bet that commentators focused on was that the European governments would not default before the maturity of the short-term trades, and the transactions allegedly would have worked out had MF Global survived. (Note that press commentary has focused on an Italian bond). The problem has been widely described as one of short-term price moves, namely, that Corzine and other managers allegedly did not know that if the price of the maturing bonds it bought fell more than 5%, it would have to post more collateral, and that adverse price moves triggered the liquidity crisis.

It turns out this description of the trade isn’t accurate. It never was a real repo to maturity, as in maturity match funded externally. The funding was two days shorter than the maturity of the asset. But, no joke, MF Global dressed that up internally and somehow got accountants and regulators to buy off on this bogus characterization. And even worse, this scheme produced book profits at the expense of liquidity, the real scarce commodity at the firm:

Among the lines of business that Mr. Corzine built up to attempt to improve profitability at MF Global was the trading of a portfolio of European sovereign debt securities. These trades provided paper profits booked at the time of the trades, but presented substantial liquidity risks including significant margin demands that put further stress on MF Global’s daily cash needs.

The European sovereign debt trades were structured as “repos to maturity” (“RTMs”). In these transactions, sovereign debt securities purchased by MFGI at a discounted price were repoed back to its affiliate, MFGUK. Because the termination of the RTMs between MFGI and MFGUK was the same date as the maturity of the sovereign bond, accounting rules allowed MF Global to account for the RTM as a sale, and therefore record an immediate gain on the sale, while removing the transactions from MF Global’s consolidated balance sheet. The corresponding repo transaction between MFGUK and LCH.Clearnet (previously known as the London Clearing House (“LCH”)), however, was for a term two days shorter than the maturity date of the underlying bonds. This disparity meant that MFGUK — which turned to MFGI to provide funding — would ultimately have to finance the sovereign bonds for the two-day window, thus increasing the amount of cash MFGI needed to maintain the RTM portfolio. In addition to addition to this liquidity risk as between MFGI and MFGUK, MFGI continued to bear the risk of default of the bonds themselves…

As the Board and management were aware, the exposure from this portfolio was the equivalent of 14% of MF Global’s assets as of September 30, 2011, and was more than four-and-a-half times MF Global’s total equity, a level that was orders of magnitude greater than the relative exposure at other, larger financial institutions.

This schematic shows how the trade worked:

As we noted earlier, these transactions were given off balance sheet treatment (in the stone ages of my youth, the term of art was “defeased”, the new lingo is apparently “de-recognized”). The report accepts the claim of management that this treatment was kosher under US GAAP and flags this disclosure in the June 30, 2011 10-Q:

The Company also enters into certain resale and repurchase transactions that mature on the same date as the underlying collateral (“reverse repo-to-maturity” and “repo-to-maturity” transactions, respectively)…For these specific repurchase transactions that are accounted for as sales and are de-recognized from the consolidated balance sheets, the Company maintains the exposure to the risk of default of the issuer of the underlying collateral assets, such as U.S. government securities or European sovereign debt. The forward repurchase commitment represents the fair value of this exposure and is accounted for as a derivative. The value of the derivative is subject to mark to market movements which may cause volatility in the Company’s financial results until maturity of the underlying collateral at which point these instruments will be redeemed at par.

Query whether this disclosure was adequate. While it does flag the exposure to default risk and adverse price movements, it does not mention the hazard that proved fatal, namely, that this trade produced accounting (and hopefully in the end actual) profits but with ongoing liquidity demands that an astute reader would not anticipate existed with a trade that was a true (as opposed to internal) repo to maturity.

Top management looks even more out-to-lunch than previously thought, since MF Global had experienced large margin calls due to unfavorable price changes in the bonds used in these trades, the first time in October 2010 on some Irish sovereign debt, and an even larger haircut on Irish and Portuguese sovereign debt in September 2011.

As Michael Crimmins said via e-mail:

The repo to maturity trade that enabled MFG to disappear the position was an INTERCOMPANY trade between MFGI and MFGUK. The ACTUAL repo with the street (MFGUK to LCH) was repo to (maturity-2 days).

The external auditors and the regulators waved it through anyway.

Since the entire business model rested on this fiction, the customers were doomed at the point this was approved.

The resulting catastophe was inevitable and all the issues about chaos in the final moments and feuds between Treasury and Accounting and antiquated systems is noise.

The regulators could have shut him down on day one. Using intercompany accounting to game the regs is compliance 101 stuff, so the regulators can’t claim they were bamboozled by the slickest guy in town. They were idiots, genuinely or conveniently, you decide.

At least Lehman had the decency to pay its counterparties to rent their balance sheet to pull off their scam. Fuld must surely envy Corzine.

But sadly, this scam isn’t likely to get the attention it deserves, since the otherwise substantive report does not question the accounting characterization of this trade. And that means, yet again, the key enablers are likely to get off scot free.

Yves,

You keep trying to shame the prosecutors of our country into doing their jobs but none are in jail from the 2008 pimple that burst.

Given that the grime has become a ring worm pustule one would think it attract some serious attention but I don’t see any heading to jail here either……the underlying cancer we have must not smell bad enough yet.

Welcome back and keep up the stellar work.

Yves, before digital “money” made crime easier, tangible checks had to be used for “check kiting,” a felony.

Also, at the end you refer to the “scam.” Is this not in fact a “conspiracy.”

Like a termite infested house, not fumigating means

simply awaiting total collapse on a longer timeline.

But most people will vacate as soon as the structural

weakening is widely apparent…..so the Big Con stops sooner

than one might calculate. Trust is built up over a long

period, but lost all of the sudden and completely….too

bad sociopaths don’t care.

Our D.O.J. is no more committed to justice now than they were when Bush, Cheney, and Rove were calling the shots.

But hey, they went after John Edwards, so there you go.

~

The Bush administration prosecuted more bankers than the Obama team. Look it up.

The G.W. Bush DOJ also decided that torture was legal.

My point is the Obama DOJ is no better.

~

Oh, I know. That wasn’t a defense, but an illustration of just how pathetic Obama and his team have been.

How can the DOJ do anything? They are surrounded by lawfirms that will “pounce” once they try to do what the average Joe would expect they would do-do, whether mortgage fraud, massive contractor swindles, bribes, kick backs, military industrial looting and so froth. Let’s keep it fundamentally naive shall we? The little fish, the massive prison system, that’s where the action is, the owner ruler class moves about with the least resistance until a single individual makes the shit list. How many millions are being blown on Edwards who basically had a mistress, and tried to keep it on the down low? Three strikes for all marihuana addicts!

State Attorney Generals managed to do something, in spite of having far fewer resources than the D.O.J.

The D.O.J. did nothing** because they didn’t want anything done. The banksters paid for Obama’s election in 2008, and he rewarded them with geysers of money and freedom from prosecution.

** The D.O.J. ultimately did prevent the State A.G.’s investigations from doing any harm to the crooks.

~

What investigations? The state AGs didn’t investigate squat. They sold out — I mean settled — before they even got that far. If they’d investigated they would have had more leverage, so they didn’t — which gave them cover to fold up like a card table.

“the Bush Justice Department did successfully prosecute several CEOs after the corporate accounting scandals of the early part of the 2000s, including Jeffrey Skilling and Ken Lay at Enron, Bernie Ebbers at WorldCom and Dennis Kozlowski at Tyco, a record that far outshines the Obama Justice Department”

http://news.firedoglake.com/2012/06/03/law-enforcement-cherry-picks-small-financial-firms-for-prosecutions/

This is not an endorsement of Republicans, just an illustration of how pathetic Obama is.

Thank for this piece. What is uncovered here is the misapplication of customer funds. Pure and simple there is an actionable tort here and with a little digging an actionable felony.

Susan, A few observations.

First, contrary to first impressions Giddens is one of the good guys here.

Second, internal audits flagged poor risk controls , governance and procedures well prior to the bankruptcy, yet

we hear nothing from PWC about this or the ratings agencies.

Now back to Corzine, we read in the report that he ran a company with a fragmented reporting structure, with poor risk controls and that he decided to lever up, and personally ran the book and was part of the board of directors that kept approving the inceases in risk. Further we learn that he was very aggressive in using customer monies to help finance MF Global, if not for the Euro trade, business operations in general. He fired Michael Roseman the for providing adult supervision, and we can infer the North American CFO quit because she became increasingly uncomfortable with how MF Global was funding.

Jon Corzine was the former CEO of Goldman Sachs, a State Senator and a Governor. He knew better. That he signed off on his Sarbanes Oxley compliance along with Steenkampf when he knew according to Giddens that internal controls were not in order means that he should be acted in willful disregard of his responsibilities and should be prosecuted.

Lastly, the Department of Justice(Eric Holder) needs to explain to MF Global customers, Congress and the American People why Jon Corzine is not being prosecuted for apparnent SOX violations.

I never said Giddens was not a good guy. But he missed the significance of the not-really-a-repo-to-maturity issue, which is a real biggie. Agreed 100% that this report does tee up a Sarbox prosecution.

I’m not sure how relevant the repo to maturity aspect was here. To the extent it was, it was clearly over-shadowed by Corzine continuing to double down while aggressively using customer funds with his “alternate method” of defining excess margin, all the while checking his liquidity dashboard on a daily basis. Would not the repo-to maturity issue be bigger criticism for the auditor, PWC, who apparently is the auditor of choice for those doing funny things(e.g Chesapeake, jp morgan, aig, madoff, MF Global, and Lehman to name a few..)

You are missing the significance of getting the accountants to buy off on the non-repo-to-maturity trade. ALL the supposed RTM trades really had a two day funding gap. That appears to have led DIRECTLY led to both the profit of the trade and the ability to get it off balance sheet AND ongoing liquidity demands.

Corzine didn’t enter into any true RTM trades and presumably wouldn’t have. No dodgy sovereign debt trades, no death of MF Global (or at least the speedy, chaotic sort that led to the desperate pilfering of customer accounts). Now Corzine might have teed up other dodgy trades, but we can’t know what that counterfactual might have looked like.

Has anybody checked to see if the bonds in question matured on a Sunday?

I saw that keen diagram in FT, and 53 pages of cash shuffling boxes and arrows screamed “scam.”

But you shred it, and label all the moving parts and name the evildoers.

Welcome back!!!!

Maybe after the election Mr. Obama will have more flexibility and the jail time will start……or I am SURE Mr. Romney will jail all those who are banking his campaign.

yep, I am sure of it.

“But sadly, this scam isn’t likely to get the attention it deserves, since the otherwise substantive report does not question the accounting characterization of this trade.”

No, the real reason it won’t get the attention is two-fold:

1. The media is not going to risk advertising revenue or access given to them by The Banking Cartel.

2. Most Americans, were they actually to read this piece, would not have a fundamental understanding of it and would just shrug it off and go back to “Idol”.

In the end, let’s not forget “who” pays the bills while on the campaign trails of both Party’s.

Perhaps, but you do not show why the UK arm did the Repo to Maturity two days short? And surely different bonds had different maturities so that they were never short liquidity for the whole speculative exposure but only tranche by tranche? A government bond 2 days from maturity is either liquid at par or impaired.

Surely the moral of the tale is that margin requirements should always be a function of each trade and not depend on the credit rating of the contractants. In that way there would be no surprises except price movements.

1. I’m not sure what you mean by “tranches” here. These were maturing bonds.

2. The report clearly states that the two day mismatch led to ongoing liquidity demands. This is not speculation on my part.

Yves,

I’d like to know more how exactly the liquidity mechanic worked, and why it failed.

As I understand it, the repos were in effect a basis trade – you buy a bond at 80, repo it at 75, use coupon to pay most of the repo interest, and hope to redeem at par.

Now, I can see how moving this to RTM would remove it from your balance sheet, and pretty up the profits. I still don’t understand how the mismatch would cause problems with liquidity.

Two days out the bond should probably trade pretty close to par – I’d say that your LCH margin is going to be 2-3% (even for an Italy bond), so you’d be able to get quite a bit of cash at a drop of a hat. Your cash interest is not going to be large either, so it’s not like you suffer from a large IR risk (unless you levered up to the hilt and done a trillion of the bonds).

‘The report clearly states that the two day mismatch led to ongoing liquidity demands.’

The weighted average maturity of MF Global’s laddered sovereign bond portfolio was Oct. 2012 — that is, about one year counting from Oct. 2011 when the firm failed.

Given 3-day settlement, is a 2-day mismatch on a 365-day repo-to-maturity really such a big deal?

Assume that the match had been perfect. As peripheral European bonds dropped in price, MF Global still would have been subject to margin calls.

That is, as best I can understand, JPM demanded more margin from MF Global because its collateral was losing value, not because of a 2-day funding mismatch.

The 2 day mismatch undermines the fiction that the underlying securities were ‘sold’ via the Repo to Maturity transaction.

The intercompay repo between the MFG entities matured on maturity date of the securities. As a result of the trade with itself, the B/D could treat the securites as sold (to MFGUK) and disappear the transaction from its books. As a result the B/D obtained capital relief (i.e no capital required if its not on the books).

But in reality, the actual repo with the street between UK and LCH did not mature on security maturity date.

Absent the internal RTM transaction, MFG would not have been able to treat the securities as ‘sold’ out of the BD since the securities were contracted to be returned to MFG 2 days before maturity.

In other words, MFG never ‘sold’ the securities at all.

MF Global, Corzine may (come on now should be WILL) get away with it

http://articles.marketwatch.com/2012-06-04/commentary/32018284_1_jon-corzine-cftc-civil-lawsuit

I must admit to being a financial dufus. What is it that MFG actually bought? Was it actual sovereign bonds, or was it some form of derivative of those bonds? It would seem that if it were the bonds, and they were held to maturity and there was no default, then losing money would be impossible. Was the real problem for MFG simply cash flow, or did it in fact, lose money on these transactions? I fully understand that if bond rates are going up, which they were, the value of existing bonds, which have below-market yields, is declining. So if one does not hold such bonds to maturity, they would suffer a loss because the market value would be less than the purchase price.

Also, the term margin call seems odd here. Apparently there is more to these transactions than shown in the schematic. For there to be a margin call, MFG would have had to borrow the money to purchase the bonds. As the value of the bonds declined, the lender would demand more collateral to reduce risk. I am wondering who that might be. Who lent MFG large sums of money to play this game? Wouldn’t the obligations to its creditors be part of the balance sheet? Or was it this obligation that was effectively hidden?

Finally, not to argue with Mr. Crimmins, who undoubtedly understands this game far better than I, why does he see depositor losses as soon as the RTMs were given regulatory okee-dokee? Wouldn’t losses only occur after the value of the bonds actually declined?

I think it is great that you present some complex information on your site – but I must admit, I want a good primer on high finance to read so I don’t feel so lost.

+ 1 — would love to hear answers from the pros (Mr. Crimmins?) to your questions re the nature of what was purchased (bonds? derivatives of bonds?), why losses occurred before maturity, and the questions around the margin issues.

And they were bought on discount, too. How does that work?

The NYT adds another twist to the not really repo to maturity deal.

‘…the firm also transferred its roughly $3 billion in holdings of Italian bonds from the brokerage arm of the company to the “FinCo,” according to the trustee’s report. By doing so, the firm met its requirements without having to raise money.’

http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/06/05/to-avoid-regulatory-scrutiny-mf-global-moved-around-sovereign-debt/

Further evidence the Repo-to-Maturity was a sham transaction. By moving the underlying securities to the unregulated entity to avoid capital charges at the Brokerage unit, MFG would have had to restructure its Intercompany Repo to Maturity deal.

I’m shocked, shocked, that there is obvious fraud and corruption in the MF Global collapse!

say John right as Holder comes up and gives him a get out of jail free card:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SjbPi00k_ME

For the life of me, i cant get my head around the significance of the -2 days repo to maturity.

It seems pretty clear to me what the real plan was here for Corzine and his cheif compadres ( which doesn’t include the dutiful, loyal, out of her depth and subservient would-be patsy, Edith o’Brian)

They wanted to sell the firm in late October rather than put it into bankruptcy, and were expecting to get away with their fraud and deal with the shortfalls later. JPM and BNYM would play ball agaian once they were part of a larger, solvent ccompany. That way they get lots of bonusses and golden handshakes, rather than criticism and shame.

Unfortunatelly, their timing was out, and even John Corzine couldn’t get the regulators to ignore a missing billion and a half dollars. He forgot he wasnt at Goldman any longer.

1. This was a big trade that Corzine was using to try to get MF Global to be profitable.

2. The repo to maturity meant it was not put on the balance sheet. So the firm looked MUCH less levered than it was.

3. Had it not been treated as RPM, it is pretty certain Corzine would either not have done the trade at all or would have done it in much much smaller size.

4. Since this was the trade that killed the firm, had Corzine not done it, the firm might not have died, or might not have gotten into such an acute liquidity crisis and hence not raided customer accounts.

OK.

Got you. The repo-2 days meant they were hiding their leverage.

http://repowatch.org/

Hi Yves

Do you know why MF had its London subsidiary perform the repo with the outside party?

Is there some different accounting rule that is different in the UK that they were taking advantage of?

Page 64 of the report gives the reason for the 2 day difference in maturity of the RTM: “LCH [London Clearing House] did not want to bear risk of sovereign default”. (Ritholtz has the report at http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2012/06/mf-global-investigation/). Here are the paragraphs from pg 64 of the report that explain it:

The RTM structure was as follows. MFGUK purchased the sovereign bonds from

counterparties, the trades for which settled on the LCH. MFGUK then sold the bonds to MFGI,

although the bonds remained in MFGUK’s LCH account. MFGI recorded the bonds on its

books, classifying them as securities owned in MFGI’s long inventory book. Subsequently,

MFGI entered into an intercompany repo with MFGUK (which showed a reverse repo to

MFGI).59 Each intercompany repo was governed by the global master repurchase agreement

between MFGUK and MFGI dated July 19, 2004, as amended (the “GMRA”). On completion of

the RTM with MFGI, MFGUK entered into a further RTM with another counterparty that also

settled through the LCH.

On the trade date, MFGI recognized a gain in the amount of the difference between the original purchase price of the underlying security and the RTM sale price of those

securities to the LCH, and MFGUK recognized a gain in the amount of the markup for its role as

intermediary between MFGI and LCH. The RTM between MFGUK and the LCH, however, was

only until two days short of maturity, the reason being that LCH did not want to bear the risk of

sovereign default. For these “RTM minus two” positions, then, LCH expected MFGUK to fund

the positions for the remaining two days until the bonds matured, so that MFGUK — not the

LCH — bore the risk of issuer default during that period. MFGUK, in turn, looked to MFGI to

fund the two-day breaks.