On the one hand, given that the Eurozone remains a major economic and financial flashpoint, it is good to see a major news service like Bloomberg provide a lengthy report on a continuing existential threat, that of deposit flight, or as we have described it, a slow motion bank run. But it’s a bit surprising it has taken them this long to take notice.

If you are a cross border investor or a wealthy national, consider what the exit from the Eurozone of, say, Greece, would mean to you. Deposits will be redenominated in the national currency and will fall in value. Now if you live in Greece, you’ll see costs of imported goods rise. And if you either liked to or had reason to spend money outside Greece, you have a lot less spending power. So as periphery countries have been looking wobbly, deposits have been exiting the periphery countries and going to the core, particularly Germany. And that means the mechanism for recycling savings within the Eurozone had broken down, forcing the ECB to step in.

This problem has been visible for some time. For instance, Marshall Auerback has been telling your humble blogger and others about it since early in the spring. As we have discussed, this remains a point of failure for the Eurozone, and in the last few weeks, German leadership appears to have gotten religion. Followers of the Euro-related press may recall that German leaders in July and August were telling Greece it had to adhere to the widely-recognized-as-impossible bailout requirements, and that they were indifferent to a Greek departure from the Eurozone. The big concern was not of a Greek exit per se, but that if Greece were to leave, it would demonstrate that a periphery country departure could be one part of the endgame, and that means it would be possible for other countries to leave as well. Spanish deposits have been leaving the country at an accelerating rate over the summer. And someone apparently knocked heads in Germany. In early September, the party line became “No, we’d really like Greece to stay” and the IMF has signaled that is preparing to fudge Greece’s performance versus its targets (a necessary condition for the next release of funds, which isn’t going to Greece anyhow but its creditors, natch).

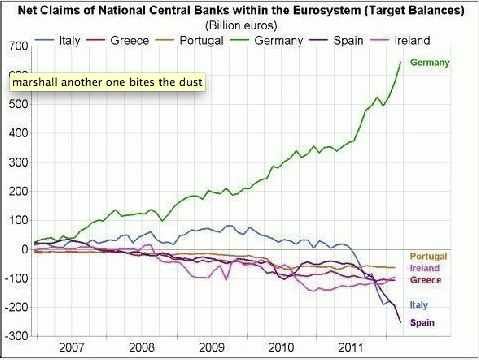

What most investors, experts, and policy makers fail to realize is that this bank run is not simply a Greek problem, which will cease if and when Greece is thrown out of the euro zone. If one looks at the Target 2 balances, the ELA, and the ECB’s lender of last resort facilities, it’s clear that this has extended into all of the periphery countries, including Spain and Italy. It may well end with Germany’s banks effectively serving as the deposit base for all of Europe. See this chart, courtesy of Gavyn Davies

Perversely, the ECB and the European authorities acknowledge none of this and seem to be doing nothing about it…

All of the recent talk about euro bonds, fiscal union and higher capital adequacy buffers for the banks are fine in their own right. But they do not deal with the immediate problem of deposit flight…

It is not necessary to restore the solvency of an institution when a bank run develops and incur all the trouble and expense that this entails. Arguably, on any honest accounting of America’s own Systemically Dangerous Institutions, they could well be insolvent, but there are no runs here because the system is backed by a robust system of deposit insurance via the FDIC. All one need do is reassure depositors that they can get their money out of the bank whenever they like…

It is important to recall that central banks were not created to control inflation. They were created to prevent the bank runs that were so catastrophic for capitalist economies in the past. For all of its protestations to the contrary, the ECB has provided this backstop when catastrophe has loomed in the eurozone, but they have done so in a very reticent manner, undermining the effects of their action by publicly proclaiming each program to be absolute the last…

But so long as there exists a healthy market skepticism that a strong supranational central bank will provide unlimited lender of last resort facilities to its weaker constituent parts, and so long as the ECB, and certain national central banks, continue to act clandestinely with a lot of threatening hard-line public talk, the runs will continue and the crisis will intensify.

Contrary to what the Germans are now indicating, a eurozone wide system of deposit insurance does NOT require the Germans guaranteeing the obligations of the Greek, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian governments. This can and should be done by the ECB, as it is the issuer of the euro. It’s also in Germany’s massive interests to have these costs born by the central bank, rather than tainting its own credit rating via persistent bailouts of the eurozone’s weaker constituent parts. Because at the end of the day, Germany is a user of the currency as well and is trapped in the same roach motel as the Italians and the Spanish, even if it occupies the penthouse suite.

Marshall provided more details on how the various recycling mechanisms (such as Target2 and the ELA) worked in this June post.

The Bloomberg story tonight (hat tip George P) serves to highlight the issue, but does it give an update as to whether anything has changed in the wake of Draghi’s announcement of OMT. Key excerpts:

An accelerating flight of deposits from banks in four European countries is jeopardizing the renewal of economic growth and undermining a main tenet of the common currency: an integrated financial system.

A total of 326 billion euros ($425 billion) was pulled from banks in Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Greece in the 12 months ended July 31, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The plight of Irish and Greek lenders, which were bleeding cash in 2010, spread to Spain and Portugal last year.

The flight of deposits from the four countries coincides with an increase of about 300 billion euros at lenders in seven nations considered the core of the euro zone, including Germany and France, almost matching the outflow. That’s leading to a fragmentation of credit and a two-tiered banking system blocking economic recovery and blunting European Central Bank policy in the third year of a sovereign-debt crisis…

The ECB has taken the place of depositors and other creditors who have pulled money out over the past two years, largely through its longer-term refinancing operation, known as LTRO. The Frankfurt-based central bank was providing 820 billion euros to lenders in the five countries at the end of July, data compiled by Bloomberg show. Irish and Greek central banks loaned an additional 148 billion euros to firms that couldn’t come up with enough collateral to meet ECB requirements.

Because central-bank financing is counted as a deposit from another financial institution, the official data mask some of the deterioration. Subtracting those amounts reveals a bigger flight from Spain, Ireland, Portugal and Greece. For Italian banks, what appears as a 10 percent increase is actually a decrease of less than 1 percent.

When financing by central banks isn’t counted, the data show that Greek deposits declined by 42 billion euros, or 19 percent, in the 12 months through July. Spanish savings dropped 224 billion euros, or 10 percent; Ireland’s 37 billion, or 9 percent; Portugal’s 22 billion, or 8 percent.The pace of withdrawals has increased this year….The difference in funding costs is reflected in loan pricing. Italian rates on consumer loans of less than one year, at 8.2 percent on average, exceeded even those in Greece and Portugal, ECB data show. Spanish consumers had to pay 7.3 percent to borrow from their banks, compared with 4.5 percent for German borrowers.

Ed Harrison also points out in the article that the latest ECB bond buying program is yet another back door bailout of French and German banks.

In the meantime, in terms of reporting actual news (as opposed to discovering old news), Delusional Economics notes that, as anticipated, plans to create a banking union by January 2013 are encountering political roadblocks which means the deadline will not be met. Like Auerback, he believe that achieving a full banking union isn’t pressing, but getting a deposit guarantee is. But he describes the impediments:

The whole point of having a supra-Eurozone backed insurer is that deposit holders in any participating country know that their savings are backed not just by their own national government, which may be struggling, but by all participating governments. In practice this should significantly reduce the outflow of deposits because, although probably not perfect, periphery banks will be seen as being considerably safer than they do today. Of course, as the article above says, deposits have been flowing towards the EZ’s stronger countries shoring up their banks so there is little incentive for France and German, especially, to support such a program.

But to be fair, German lawmakers aren’t the only ones with concerns about the new program. The head of the European Banking Authority thinks the proposal will create a two-tier banking system in Europe with rules applied differently in euro and non-euro countries:

Speaking to lawmakers in the European Parliament, Andrea Enria, the chairman of the European Banking Authority, warned that the union, forming a united front among euro zone countries to protect their lenders, risked seeing one set of rules applied to banks under the ECB’s watch and another to those outside.

“We risk a polarisation … between the euro area, with single rules and supervisory practices, and the rest of the (European) Union, which would operate with a still wide degree of national discretion in … applying the single rulebook.”

In his first public remarks since the announcement of the proposal, the Italian economist said that although banking union was something that “needs to be done now”, the challenge would be “finding the right glue to keep the single market together”.

His remarks reflect a concern shared by many countries that rules such as those on capital, that dictate how much banks must hold in reserve for losses, could be applied differently.

Yves here. So as much as the deposit flight problem needs to be solved sooner rather than later, it looks like it will require time or a crisis to achieve resolution. I don’t think it’s hard to guess which one I’d bet on.

.

Yep! we are building up to a good crisis and it will be interesting to see how it will be taken advantage of both in the US and the EU.

Is that really Italy going of the cliff in the graph? Wow! What the hell happened there? Another of GS ploys with one of their own in charge?

Does Germany have deposit guarantees on its domestic banks?

Most of Germany’s domestic banks are insolvent *due to making bad mortgage loans in Greece, Spain, Portugal, etc.*

So if the depositors from outside Germany move their money, then one of these will happen:

(1) the German banks go under and people wonder why they moved their money

(2) the German government bails out EVERYONE by bailing out the German banks (which actually works as a fiscal transfer)

(3) the Germans attempt to discriminate against foreign account holders, which will blow up the EU completely

(4) the Germans attempt to change the law to get the rest of the EU to bail out the German banks

I’d bet on #4.

I’ll go with #2.

De Grauwe has a good proposal to kill this feast: link conversion to german residents.

http://www.voxeu.org/article/how-germany-can-avoid-wealth-losses-if-eurozone-breaks-limit-conversion-german-residents

That would be essentially criminal behavior on the part of Germany; trying to get the benefits of the eurozone without taking on the costs. If they tried it the EU would dissolve within weeks.

It’s surprising that a rational and perceptive author like DeGrauwe has come out with such an unfortunate proposal.

In the quoted article, DeGrauwe claims that after a putative eurozone breakup, “Many non-residents may try to convert their euros into marks – creating a situation where too many marks are in circulation to be consistent with price stability. If that happens, inflation would set in and German residents would experience wealth losses related to the Eurozone’s demise”.

This “inflation risk” is highly questionable, however. After breakup, the new mark would surely appreciate and this would bring deflationary, not inflationary pressures on the German economy. It would threaten her exports, contracting aggregate demand.

But the presence of deposits from periphery countries could help countervail this tendency if their holders decided to convert them, even if only partially, into German exports to the periphery where they reside. This would function as a stabilizing mechanism for a post-euro economy.

We can conclude, then, that non-resident deposits flowing into Germany are a benefit for her and pose no threat, inflationary or otherwise, to her economic future. As a matter of fact, this recent excitement over Target2 “risks” is quite likely just one more instance of economists speculating over possible solutions to a non existent problem

I too have been saying for some time that all of these supposed deals with the periphery are really nothing more than a backdoor bailout of Northern banks. The Northern governments are not bailing out their banks directly. Rather they are using the governments and banks in the periphery as a pass through for the bailout funds. In doing so, they leave the periphery governments as the ultimate bagholders for the bailouts and they gain great leverage over the governments of the periphery, their policies and their commons.

I wonder if anyone has considered how all of these currency flows to German banks could spark, in the event of the eurozone breaking up, the very inflation in Germany which the Germans supposedly so much want to avoid. The euro is a call on the production of the whole of the eurozone. But with their concentration in German banks in the event of a conversion to a national currency or a smaller Northern eurozone would become calls on the production of Germany or the smaller monetary zone. Unless the velocity of these deposits remained close to zero, I would think internal inflation would be the natural result.

One way the Germans could get around this, at least partially, is if in a breakup they discounted the deposits of periphery account holders. Interestingly, such a move would negate the rationale for the current runs.

In the short term, it seems that Spain is suffering more from the outflows than Germany that is running a more medium term risk through TARGET 2.

Continued capital outflows from Spain is another point of pressure on the Spanish Government to request a formal bailout, which hopefully will come by October. The bailout would allow the ECB to intvene massively on Spanish debt. A mix of continued Spanish reforms (and not only mindless austerity) plus radically lowered financing costs could hopefull, over time, reverse the trend and allow money to trickle back into Spain.

A voir.

The ultimate cause of deposit flight from peripheral countries to the core is that savers do not trust in peripheral gov’ts because these gov’ts are not implementing the real structural reforms to solve the big issue: Corruption. The States of peripheral countries are seriously sick of a cronic disease of corruption, the political classes of those countries are mostly composed of crooks.

When looking at the problem from this point of view it is reasonable that German, French, banks are being bailed out. They lent in good faith to the south as a novel investment opportunity but a very significant part of those resources went to a predatory political class and its cronies, and they are still in power. Nothing is being done to cure the disease, not only that, the Greeks, Spaniards actually re-elected the crooks, and in Italy a technocrat had to be put in power by Germany but still under him the widespread corruption continues unabated.

In Spain from the royal family down to municipalities there are thousand party operatives exploting every opportunity to steal money from the public purse. In Italy there is a recent scandal about the kind of things parties spend the money they receive from decent working citizens. No need to give details about Greece.

The deposit flight is just a symptom of a serious disease in the southern European States. So when Auerback (as quoted here) says:

“But so long as there exists a healthy market skepticism that a strong supranational central bank will provide unlimited lender of last resort facilities to its weaker constituent parts, and so long as the ECB, and certain national central banks, continue to act clandestinely with a lot of threatening hard-line public talk, the runs will continue and the crisis will intensify”

I think that he as well our humble blogger and many readers here do not understand that they are advocating to provide unlimited lender of last resort support to the crooks that parasitize the southern European States.

Racist BS. The banks where actual criminal corruption has been identified… are in Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands, Belgium….

Read this:

http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2012/09/08/actualidad/1347129185_745267.html

It’s long and in Spanish. I fully agree with the author. His book on his theory of the Spanish political class will be published next year. This is an advance.

How is it racist to argue that the political class of non-core countries is FAR MORE corrupt than of the core countries?

Do you honestly believe that an Italian pol is less corrupt than an German pol?

Yves,

You say that “…deposits have been exiting the periphery countries and going to the core, particularly Germany. And that means the mechanism for recycling savings within the Eurozone had broken down, forcing the ECB to step in”.

Sorry, but this is not so.

The Target2 mechanism can absorb all such deposit transfers from the periphery to the core countries of the eurozone without putting the euro system at risk. At the end of the day said transfers become liabilities of the NCBs (National Central Banks) of periphery countries and assets of the Bundesbank and other NCBs of the “core”. These balances can build up (or down) indefinitely, to virtually unlimited amounts – and this is a feature, not a bug, of the system.

Target2 has also guaranteed that after the 2008 crisis, when banks stopped lending to one another across the eurozone, the current account deficit countries could keep financing their imports, thus avoiding the curse of a “sudden stop” .

And, via Target2, the PIIGS could also keep financing their budget deficits if they chose to. Yes, you heard me well: they could regain monetary sovereignty within the eurozone and avoid austerity if they so willed. Unfortunately, however, the periphery governments have been too afraid of Germany and of the ECB to use Target2 rules in defense of their own best interests.

So I think this blog should be more prudent in its criticisms of Target2. It is an extremely well conceived mechanism that guarantees smooth payments and transfers across the eurozone. It is flexible enough for the PIIGS to use it to further their interests (if they only knew – and were courageous enough to act). And the hysteria that has been growing around its supposed (read: imaginary) risks only reflects the generalized ignorance of pundits – including many economists who should know better – in matters involving the technical, accounting rules of the eurosystem.

This topic needs a full article, Yves. What could a properly Keynesian government of (say) Spain actually do with Target2?

Yes. Please.

An explanation of how Target2 works and the implications of where the liabilities pile up on the balance sheets of the core and peripheral countries central banks would be helpful.

Most analyses I’ve seen don’t take the next step of thinking about what would happen to the assets and liabilities on the balance sheets of all the eurozone central banks when the euro breaks up. I suspect Draghi has thought deeply about that and how the LTRO, ELA and Target2 all play out in a euro break up.

It appears to me Draghi’s ECB measures combined with the location of Target2 balances may also help protect periphery countries, particularly Italy, in a break up.

A great starting point for understanding the Target2 mechanisms is the following presentation by Karl Whelan at the Bank of England (on June 26, 2012):

http://www.karlwhelan.com/Presentations/Whelan-BoE.pdf

‘Target2 balances can build up (or down) indefinitely, to virtually unlimited amounts – and this is a feature, not a bug, of the system. It is an extremely well conceived mechanism that guarantees smooth payments and transfers across the eurozone.’

‘Unlimited amounts’ and ‘well conceived’ don’t belong in the same sentence. So it’s good that you prudently separated these claims by a couple of paragraphs.

I’ll bet you 10,000 Nueva Pesetas that Target2 proves to be unsustainable.

It’s the euro that may prove unsustainable – not Target2.

By using the mechanisms available (under Target2) to finance their budget deficits the periphery governments would (if only they dared) transform the eurozone into a transfer union, through the back door.

And without a full transfer union in place the euro will indeed be unsustainable.

I think a better way to say it is that the Eurozone already is a transfer union. That is the problem. Germany already exports its products, including German Euros in its banks & imports too little, accumulating claims on the periphery, directly or through the ECB.

The only way for this to continue is with “fiscal transfers”, which as Wray says, Yes it is “fiscal”, no it is not “transfer”. The only solution is as you say, a “full transfer union” with the transfers Germany is addicted to & the compensating “fiscal transfers” – to the benefit of all. Or breakup.

Germany is helping cause enormous negative externalities – instability & unemployment in the periphery – which makes it only just for the periphery to redress this with some “seignorage”, by Target2 bond issuance tricks or whatever else.

“And, via Target2, the PIIGS could also keep financing their budget deficits if they chose to. Yes, you heard me well: they could regain monetary sovereignty within the eurozone and avoid austerity if they so willed. Unfortunately, however, the periphery governments have been too afraid of Germany and of the ECB to use Target2 rules in defense of their own best interests.”

Well, the Greek gov’t could start printing euros too, they have the printing machines in Athens, why not?

Wait, it has happened already :

http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/ecb-prints-money-for-greece-to-buy-time-for-athens-a-848989.html

http://www.rantfinance.com/2012/08/08/european-ponzi-comes-full-circle-greece-is-now-printing-euros/

Just imagine what Cisco could have done with Target2 back in 2000, when it’s market value was as high as Apple’s is today.

Instead of cutting off vendor financing to the hundreds of companies that had no business buying Cisco products, it could have continued fronting them billions of dollars, incurring a Target2 A/P on its balance sheet.

Forever and Ever.

Heck, with Target2, Cisco would have a market value of US 2T or more today.

There’s more than a bit of straw manning in your comment. There is nothing inaccurate about the statement you used as a point of departure for your discussion of Target 2. If Target 2 were sufficient to deal with the quiet run, why would Draghi have needed to introduce the OMT?

And as for further discussion, let me turn over the mike to Marshall Auerback:

Look, Target 2 per se is not the problem. But this does not alter the basic fact that the original design of the euro did not take into account the strains which would be placed on this mechanism if a country like Spain were to run a large and persistent balance of payments deficit (on current and private capital account) against Germany, which is what has been happening.

A balance of payments deficit means that Spanish residents are making larger outgoing payments to (say) Germany than German residents are making to them. Since 2008, the outflow has been driven by private sector capital flows, not by a current account deficit, but it still needs to be financed. So how does this outflow of private money actually get financed? It gets financed by an equal and opposite flow between the central banks. As a result, the Bank of Spain builds up a debit and the Bundesbank builds up a credit.

I think Gavyn Davies explained this best:

In the case of two completely independent countries, these debits and credits would get settled by a payments flow of between the relevant central banks. Under the Gold Standard, this flow would be in gold itself. Under the Bretton Woods system, it would be in dollars. In either case, the outflow of official reserves would force Spain to take steps to eliminate its balance of payments deficit by tightening monetary policy or allowing the exchange rate to depreciate, so the problem would, in principle, be self correcting.

The key difference between these situations and the euro mechanism is that the debits of the Bank of Spain never get settled at all; they just get larger and larger, for as long as the Spanish balance of payments imbalance persists. And the same applies to the “credits” of the Bundesbank. This is why the Target 2 imbalances inside the ECB balance sheet have grown so large in recent years. As long as the national central banks are willing to allow these imbalances passively to rise, then the single currency simply cannot break up. That is what makes it a single currency.

However, as Mr Draghi has now implicitly acknowledged, the markets are no longer convinced that the Target 2 imbalances will be allowed to rise without limit. Although the Bundesbank has pointed out many times that Germany’s credits under this system are against the ECB, and not against any individual country, potential Target 2 losses after a euro break up have become a political issue within Germany, undermining market confidence in the ultimate stability of the euro.

It is risky for a central banker to acknowledge that the payments system on which the currency stands may not be fully credible. Mr Draghi could simply have repeated the old line that the operation of the Target 2 system is enough to ensure that the euro can never fall apart. By admitting the reality that the system is no longer 100 per cent credible in the eyes of the market, the ECB president has invited investors to ask whether his proposed interventions are powerful enough to deal with problem he has raised.

This is the great irony. Germany risks scoring an “own goal”. The more they disrupt the Targets 2 payment system, the more they risk blowing the whole system apart. And if that happens, how do they enforce their counterparty claims?

In the current situation, assuming that, say, Spain goes bust. In that situation, Germany’s losses are capped at 28% in relation to its contribution to Europe’s System of Central Banks. And even that might be overstating the magnitude of their potential losses within the existing system, because I believe that whereas the ECB has A LEGAL OBLIGATION to distribute its profits to the national central banks, there appears to be no corresponding obligation for the individual member states of the EMU to make good the losses when the ECB experiences them (and why should they, given that the ECB, as the sole issuer of the currency, can operate with no equity).

That’s a more ambiguous point, but the main consideration is that if Germany blows this all apart, then all of a sudden, its counterparty risks are no longer capped, and it is trapped.

But Berlin inexplicably fails to see this.

Either they are playing a brilliant game of poker, or they are being penny wise and pound foolish, extracting a literal pound of flesh a la Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice”. In the great Shakespearean comedy, Shylock agrees to lend money to Bassanio on the credit of Antonio, Shylock’s Christian rival.

Shylock, suspicious of Antonio, sets the security as a pound of Antonio’s flesh. When Antonio’s merchant ventures fail and he cannot come up with the money to pay off Bassanio’s loan, Shylock demands the pound of flesh, which will surely kill Antonio. Of course, in the end, Shylock is foiled. Dressed as an eminent judge, Antonio’s indirect beneficiary Portia takes Shylock’s insistence on the letter of the bond to its absurd conclusion. The bond specified only a pound of flesh, she maintains, but “no jot of blood.”

In much the same way, Germany’s ongoing insistence on its pound of Spanish, Italian, Greek, or Irish flesh via further fiscal austerity is impossible to secure without spilling further massive quantities of blood from the periphery body politics. Like Shylock, Germany apparently fails to appreciate extracting too much flesh from the borrower ultimately does draw away its lifeblood, making repayment impossible. Berlin is as trapped as Shylock. Only the ECB as “judge” can offer a way out.

“If Target 2 were sufficient to deal with the quiet run, why would Draghi have needed to introduce the OMT?”

Well, he and his acolytes want to seize the opening provided by the crisis in order to become the consecrated semi-dictators of economic policy in the euro area. They now propose to buy periphery bonds in exchange for ever-lasting austerity. Not a bad deal for unelected technocrats.

The central bankers are not academic economists living in fairy-tale land. They are perfectly aware of the possibilities provided by Target2 – and they don’t like them. The OMT proposal was a very clever tactical maneuver designed to concentrate even more power at the hands of the ECB – at a time when the southern countries seem paralyzed and unable to defend themselves. And it may well reward its authors with the intended (austerian) results, unless the periphery countries wake up to the fact that they do have the necessary weapon to mount a successful counter attack.

This weapon has a name: Target2.

‘It is important to recall that central banks were not created to control inflation. They were created to prevent the bank runs that were so catastrophic for capitalist economies in the past.’

True as far as it goes … but it’s a bit like saying central banks weren’t created to control the internet. Neither the internet nor chronic inflation existed when central banks were formed; no one even imagined a need to ‘control inflation’ under a redeemable currency regime.

Just as declaring drugs illegal creates a never-ending need to control drug trafficking, abolishing currency redeemability creates a permanent need to manage its deleterious results.

From a bureaucratic point of view, such wholesale mission creep is a boon, not a bug.

Perhaps not chronic, but certainly acute inflations and deflations existed prior to central banks.

no one even imagined a need to ‘control inflation’ under a redeemable currency regime. Well, Mitchell-Innes & others did, considering the gold standard possibly inflationary, if there were major gold discoveries, which arguably did happen. In any case, all currencies are still redeemable for the main thing they were always redeemable for – extinguishing tax liabilities. Most people consider “being out of jail” more valuable than a gold nugget.

Bank runs would be impossible with ethical (100% reserve) lending.

They would also be impossible with common stock as private money since common stock is not redeemable.

But hey, let’s keep the present system. Musical chairs is so much fun, no?

Jose Guilherme: “The Target2 mechanism can absorb all such deposit transfers from the periphery to the core countries of the eurozone without putting the euro system at risk”

This seems circular. The euro system is at risk precisely because of big trade imbalances, loans from the core to the periphery, and now capital flight. In the event of a breakup, a lot of those Northern credits in the Target 2 system will turn into losses. Meanwhile those foreign euros parked in German banks will remain fully realized (that is not depreciated) calls on the German economy.

Also Target 2 is not unlimited. It is limited by amount of collateral that underlies the transfers.

Target 2 presupposes a well functioning economic system. Facts not in evidence.

All other things being equal, a new Deutsch mark would likely appreciate. But all things are not equal, there are the loss of much of Germany’s export markets, the unrealized losses of German banks on their loans to the periphery, the burden of foreign deposits in the conversion to the new mark, and the need to recapitalize an insolvent German banking sector. I think a straight conversion of the foreign deposits to new marks would be inflationary, but most of the other problems look deflationary in character. And when I say deflationary I mean internally, not in terms of a new mark international exchange rate. It would probably rise against most of the other post-euro currencies, but could fall against other currencies like the dollar, yen, and yuan.

“Also Target 2 is not unlimited. It is limited by amount of collateral that underlies the transfers.”

But the ECB can continue to relax its collateral requirements so that it’s effectively unlimited.

Exactly! Collateral requirements will have to be relaxed. It’s not optional, it’s a necessity. Otherwise the payments system would simply freeze, putting the very survival of the eurozone at risk.

So TARGET2 is a weapon without ammunition; the ammunition has to be provided by the ECB; ergo, periphery countries cannot just will themselves into financing their budget deficits via TARGET2.

TARGET2 “merely a scorecard that reflects the

long-term outcomes of the lending and collateral

policies of the ECB.”

See :

http://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_brief/2012/pdf/eb_12-08.pdf

You forgot to mention the last sentence of the Richmond Fed paper:

“Placing arbitrary limits on TARGET2 balances at this stage

would not solve anything. To the contrary, TARGET2 restrictions would unnecessarily constrain cross-border transactions and ultimately defeat the purpose

of the EMU”.

Translation: the ECB has no choice but to provide the “ammunition”, otherwise the eurozone (that they are bound by Treaty to defend) is toast.

Dear Jose, I did not forget the part you are quoting; it was just irrelevant to the argument (and I don’t agree with your ‘translation’). Look, I was intrigued by your assertion that periphery countries may just will themselves into deficit spending via TARGET2; you made it look as if these countries could do it automatically; fact is they cann’t do that via TARGET2, they have to get the go ahead of the ECB via collaterals and such. So now the current situation these countries are in makes a lot more sense.

TARGET2 though does provide some protection to periphery countries just because it keeps a record of credits and debits between national central banks and the ECB and right now for Germany (and France) it is not convenient to break apart the EMU because losses would cristalize.

The problem with bank deposit insurance is that it effectively forces the issue requiring the trans-Atlantic banking system’s insolvency be promptly addressed, this particularly in light of the fact resistance to going the hyperinflationary route only is growing among EMU member states with the most to lose (hyperinflation being the means preferred by imperial scammers for masking the banking system’s insolvency). So, deposit insurance is a non-starter because the supra-national imperial banking dictatorship whose European debt trap scam called the euro now leaves the continent well-poised for conquest (featuring theft of physical assets and destruction of sovereign government, this while maintaining the illusion of the banking system’s solvency through hyperinflationary bailout) would be wrecked should the still thriving fraud of the trans-Atlantic banking system’s solvency be irrevocably challenged (as it should be now that QE has become open-ended).

Hugh:

Target2 presupposes the existence of a currency union, an entity that is simply not viable in the absence of unilateral transfers from the core to the periphery – see the examples of the U.S., Brazil (where I live) etc. for instances of real-life currency unions.

So what Target2 guarantees is, quite simply, that a euro in, say, Portugal is the exact equivalent of a euro in Germany.

This explains how, after the 2008 crisis when interbank markets froze, Target2 enabled the current deficit countries (like Portugal and Spain) to keep financing their imports from the core.

And whenever depositors massively flee the PIIGS’ banking systems towards Germany, Target2 provides for smooth, no hassle transfers transfers.

Notice that in 2007-8, when the markets had a brief panic attack over the health of the German banking system, Target2 functioned in the opposite direction enabling massive transfers from Germany´s banks to other EMU countries as the Bundesbank accumulated negative balances versus the ESBC (European System of Central Banks).

And periphery countries, if they so much as dared it, could order (tommorrow!) their state-owned banks to accept their newly-issued Treasury bonds, open up deposits in the government’s name and then transfer said deposits to Germany or France in order to pay off old issues of maturing T-bonds held in the accounts of commercial banks of the core countries. The balances of these operations would accumulate in the ESCB (Target2)system.

Thus default risk would be eliminated and periphery deficits would keep being financed, with no need to seek foreign aid and accept the disastrous conditions attached to the Troika packages.

If the ECM tried to react by dictating that periphery T-bonds could not be eligible as collateral (thus violating their own recent practice in Ireland and Greece, where tens of billions of euros have been advanced to banks under the weak collateral rules of ELA) that would mean, in practice, an order for suspension of payments from and to said countries – that is, expulsion from the eurozone. Likely, even the all-powerful ECB would balk at such a move in the absence of political cover from Germany and other member countries.

So there you have it. Target2 has enabled the survival of the eurozone until now. It’s now up for the PIIGS to use it in order to defend their economies and simultaneously save the EMU in its only possible form: a transfer union.

But that is simply jaw-dropping – and potentially proof that the EU is a vast criminal enterprise, using financial warfare (as Michael Hudson puts it) to commit crimes against humanity? I’ve followed this unfolding crisis for some time, hewing to the notion of forensic audit and debt cross-cancellation or a clean slate as the ultimate recourse, and listening to world-renown economists blather on about the need for a fiscal union. But you’re saying a clearinghouse mechanism provides a solution and a form of resistance well short of default and Grexit? And this is well known but hitherto unremarked? Papers and references please!?! And your Nobel nomination is in the mail…

Well, some of the references would be papers on Target2 by Peter Garber (from Deutsche Bank, a top expert on the subject who’s been writing about it for almost two decades), John Whittaker (Lancaster University), Marc Lavoie, Karl Whelan, etc.

Unfortunately, pundits have trouble following more technical subjects such as payments systems within a currency area and neoclassical economists don’t usually like accounting – a subject many consider to be below their (supposedly) high level of intellectual sophistication. Maybe this explains why the periphery countries have – until now – failed to consider the possibilities available to them under Target2.

But this could (and should) change. It’s about time for the victims to turn the tables around against their torturers – by simply applying the rules of the system for their own benefit.

Thank you very much for the pointers. Was just looking at Garber’s 1998 paper when I saw the refs & your enlightening comments.

You may also like to check out Garber’s December, 2010 paper: The mechanics of intra euro capital flight. It’s availabe on the web.

What’s impressive about Target2 is that it can accomadate either import financing, capital flight or deficit financing by member states.

Strangely, the last option is the only one that has never been used. This must change if the PIIGS are to survive the latest austerity onslaught that keeps killing their economic performance.

here’s a nice touch: ECB Shows Off New Headquarters

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2012/09/20/ecb-shows-off-new-headquarters/?mod=WSJBlog

How any progressive can support the ECB is beyond me.

For a progressive to support the ECB is to support Bernanke as he unilaterally crafted fiscal policy from the Fed, and imposed it on every American, “because the country is about to implode”.

How would progressives feel about Bernanke unilaterally converting Medicare into a voucher program? Yet, these same progressives cheer as Draghi enacts policies that do the same in the EZ.

Yves- The FT has been covering this consistently since late last year.