By Simon Johnson, Peter Boone. Johnson is Professor of Entrepreneurship, Sloan School of Management, MIT and CEPR Research Fellow. Boone is Research Associate, Centre for Economic Performance, LSE. Originally published at VoxEU.

Industrialised countries today face serious risks – for their financial sectors, for their public finances, and for their growth prospects. This column explains how, through our financial systems, we have created enormous, complex financial structures that can inflict tragic consequences with failure and yet are inherently difficult to regulate and control. It explains how this has happened and why there are more and worse crises to come.

There is a common problem underlying the economic troubles of Europe, Japan, and the US: the symbiotic relationship between politicians who heed narrow interests and the growth of a financial sector that has become increasingly opaque (Igan and Mishra 2011). Bailouts have encouraged reckless behaviour in the financial sector, which builds up further risks – and will lead to another round of shocks, collapses, and bailouts.

This is what we have called the ‘doomsday cycle’ (Boone and Johnson 2010). The cycle turned in 2007-8 and was most dramatically manifest in the weeks and months that followed the fall of Lehman Brothers, the collapse of Iceland’s banks and the botched ‘rescue’ of the big three Irish financial institutions.

The consequences have included sovereign debt restructuring by Greece, as well as continuing problems – and lending programmes by the IMF and the EU – for Greece, Ireland, and Portugal. Italy, Spain and other parts of the Eurozone remain under intense pressure.

Yet in some circles, there is a sense that the countries of the Eurozone have put the worst of their problems behind them. Following a string of summits, it is argued, Europe is now more decisively on the path to a unified financial system backed by what will become the substance of a fiscal union.

The doomsday cycle is indeed turning – and problems are undoubtedly heading towards Japan and the US: the current level of complacency among policymakers in those countries is alarming. But the next turn of the global cycle looks likely to hit Europe again and probably harder than before.

The continental European financial system is in big trouble: budgets are unsustainable and growth is nowhere on the horizon. The costs of bailouts are rising – and the coming scale of the problem is likely to undermine political support for the Eurozone itself.

The structure of the doomsday cycle

In the 1980s and 1990s, deep economic crises occurred primarily in middle- and low-income countries that were too small to have direct global effects. The crises we should fear today are in relatively rich countries that are big enough to reduce growth around the world.

The problem is that the modern financial infrastructure makes it possible to borrow a great deal relative to the size of an economy – and far more than is sustainable relative to growth prospects. The expectation of bailouts has become built into the system, in terms of government and central bank support. But this expectation is also faulty because, at times, the claims on the system are more than can ultimately be paid.

- For politicians, this is a great opportunity.

It enables them to buy favour and win re-election. The problems will become apparent, they calculate, on someone else’s watch. So repeated bailouts have become the expectation not the exception.

- For bankers and financiers of all kinds, this is easy money and great fortune – literally.

The complexity and scale of modern finance make it easy to hide what is going on. The regulated financial sector has little interest in speaking truth to authority; that would just undercut their business. Banks that are ‘too big to fail’ benefit from giant, hidden and very dangerous government subsidies. Yet despite repeated failures, many top officials pretend that ‘the market’ or ‘smart regulators’ can take care of this problem.

- For the broader public, none of this is clear – until it is too late.

The issues are abstract and lack the personal drama that grabs headlines. The policy community does not understand the issues or becomes complicit in the schemes of politicians and big banks. The true costs of bailouts are disguised and not broadly understood. Millions of jobs are lost, lives ruined, fiscal balance sheets damaged – and for what, exactly?

Over the past four centuries, financial development has strongly supported economic development. The market-based creation of new institutions and products encouraged savings by a broad cross-section of society, allowing capital to flow into more productive uses. But in recent decades, parts of our financial development have gone badly off-track – becoming much more a ‘rent-seeking’ mechanism that draws support from politicians because it facilitates irresponsible public policy.

- The question is: Who will be hurt next by this structure?

There are three prominent candidates: Japan, the US, and the Eurozone.

Japan’s long march to collapse

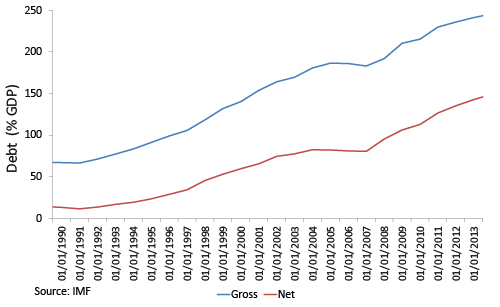

Figure 1 shows the path of Japan’s ratio of debt to GDP over the last 30 years, including IMF forecasts to 2016.

Figure 1

This is a worrying picture:

- Japan has a rapidly ageing population.

The average Japanese woman today has 1.39 children, far fewer than is needed to replace the elderly. This means that the total population is set to decline by 26% by 2050. Having peaked in the mid-1990s, the country’s working age population will decline by a staggering 40% between 1995 and 2050. Naturally, many of the ageing Japanese have been saving for their retirement for decades. They deposit those funds in banks, buy government bonds, hold cash savings or buy Japanese equities.

- Japan’s growth is slowing.

With an ageing population and slower growth, the broad outlines of responsible policy are straightforward. Japan should become a big investor in countries with younger populations, providing the capital investment needed to generate growth. Those countries can then return the savings to the Japanese as they retire. Singapore’s government does just that via one of the world’s largest investment funds.

Instead, for the last two decades, Japan’s government has been running large deficits, borrowing and then spending the savings of the young. When the elderly finally demand their savings back in the form of pensions, the government will need to reduce its budget deficit of 8% of GDP and start running a sizeable budget surplus. Unless there is a sudden burst of romance and fertility, there will be far fewer Japanese taxpayers in the future to pay this debt.

The government has not been willing to raise taxes in a timely manner to match its spending. The latest agreement is for a modest (5%) increase in the retail sales tax, which would only be fully implemented in 2015. Why would it do so in the future when the burden on the remaining workers will need to be ever larger?

Japan is saved from immediate pressure by the fact that about 95% of its government debt is held by domestic residents. As long as these investors are satisfied with very low – or perhaps negative – real rates, this situation can continue.

But sooner or later, Japan’s dreadful fiscal mathematics will catch up with the government. There is no sign yet of a broad loss of confidence, but major shifts in market sentiment are not typically signalled in advance.

America’s reckless private finance

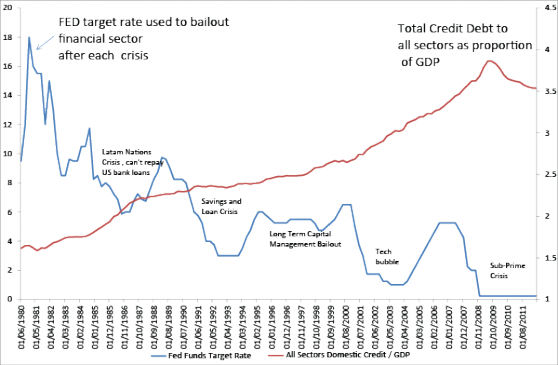

In the US, the symptoms are different. Figure 2 illustrates the US version of the doomsday cycle: the rise of total credit as a fraction of national income. Major players in the financial system have become too big to be allowed to fail – and consequently receive large subsidies.

Figure 2

The latest crisis has led to the largest monetary and fiscal bailouts on record. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the final fiscal impact of the crisis of 2007-8 will end up increasing debt relative to GDP by about 50 percentage points. This is the second largest debt shock in US history; measured in this way, only the Second World War cost more. (For more detail, see Johnson and Kwak 2012.)

The alliance that leads to unsustainable finance here is simple: the US financial system earns large ‘rents’ (excess returns to labour and capital) from the implicit subsidies offered by taxpayers. These rents finance a massive system of lobbyists and campaign donations that ensures ‘pro-bailout’ politicians win elections regularly.

Each time the US has a crisis, politicians and technocrats admit their errors and buttress regulators to ensure that ‘it never happens again’. Yet still it happens, again and again. We are now on our third round of the so-called Basel international rules for banks, with the architects of each new reform admonishing the previous architects for their mistakes. There’s no doubt that the US will someday soon be correcting Basel 3 and moving on to Basel 4, 5, 6 and more.

The problem that the country faces is that with each crisis, the financial risks are getting larger. If continued in this manner, bailing out the system will eventually be unaffordable. When the US finally runs out of enough savers to buy the bonds needed to bail out the system, it will suffer the ultimate collapse. (For more detail, see Schularick and Taylor 2012.)

Roughly half of all US federal debt is currently held by non-residents. So US fiscal policy remains viable only as long as the dollar is seen as the ultimate safe haven for investors. But what is the competition? Japan is not appealing today as a haven and it is unlikely to become more appealing in the near term. A great deal of the prospects for the US budget and growth therefore rest on what happens in the Eurozone.

The Eurozone: Flawed dreams

There is no sign that the Eurozone will emerge from crisis any time soon.

The incentive structure of the Eurozone ensured that each country’s financial sector clamoured to join it. The key feature that made it so attractive was the liquidity window at the ECB.

For smaller countries, the ECB is a modern day Rumpelstiltskin. Rather than spinning straw into gold, the ECB converts unattractive government and bank-issued securities into highly liquid ‘collateral’ that can be readily swapped for cash from the ECB. This feature instantly made sovereign and bank bonds very attractive debt instruments. Knowing that the borrowers had essentially unlimited access to liquidity from the ECB, investors became willing lenders at low interest rates to all banks in the Eurozone.

Given such attractive features, it is easy to understand why 17 countries mastered the political debate to join the Eurozone. It is also easy to understand how the system got abused and why it will be so difficult ever to make it ‘safe’. If the Japanese can’t control their public finances and if the US can’t control its too-big-to-fail banks, the added complexity of merging 17 regulators and 17 national governments into a system where someone else can be made responsible for bailing out the intransigents seems a financial and regulatory nightmare.

Such a system is sure to be crisis-prone. The Federal Reserve and the US federal government’s attempt to provide bailouts when there is trouble in the US. But in Europe, the bailouts are only partial. No country has a ‘lender of last resort’ like the Federal Reserve or the Bank of Japan – so markets are now learning that large risk premia are needed to reflect default risk in troubled countries.

Flexible exchange rates would undoubtedly make it easier to manage these crises. Devaluations instantly reduce wages and raise countries’ competitiveness. If Greece had managed a large devaluation, it could probably have avoided much of the unemployment and social turmoil we see today. Instead, each troubled country in Europe now suffers when having to force down wages and prices during adjustment.

This system poses great dangers to global financial stability. The Eurozone faces myriad problems, including insufficient bank capital, high levels of private and public debt, and the chronic inability of some member countries to grow.

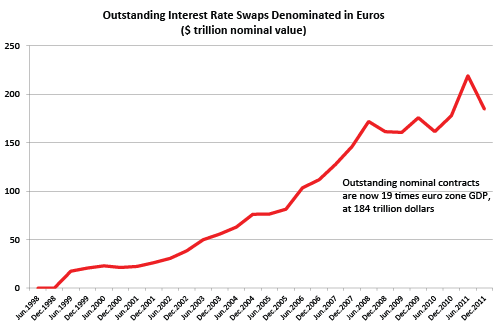

It is now common to hear policymakers blackmailing populations: unless the Eurozone survives, tragedy will result. And it is true that tragedy will result; we only need to look at the rise of complex derivatives and the dangers they pose were the Eurozone to dismantle. (For a broader discussion of Europe’s problems, see Boone and Johnson 2011 and 2012.)

Figure 3 illustrates the growth of euro-denominated interest rate derivatives, the notional value of which now totals more than 10 times the GDP of the Eurozone. Regulators commonly use net figures when they consider ultimate risk for banks and this makes sense under the usual circumstances of bankruptcy. But when a currency area breaks up, the practice of netting off contracts needs to change dramatically and banks will be facing far more risks than regulators and risk officers currently report.

Figure 3

For example, if a German bank has a contract with a French bank and an opposite identical contract with a German pension fund, it can net those two contracts and report the ultimate risk as zero. (Of course there is counterparty risk, but under standard agreements, derivatives are cleared instantly at liquidation so the counterparty risks can be netted).

But if investors start to believe that there will be new currencies in each country, then the two contracts in this example are no longer offsetting so they must not be netted. It is reasonable to think that after any demise of the euro, the contracts between two German counterparties will be converted into deutsche marks, while contracts with international partners will be disputed or maintained in a euro proxy.

As a result, risk officers at banks should understand that if the Eurozone breaks up, all banks in Europe face enormous and unaccountable currency risk. Each of their ‘euro’ assets and liabilities needs to be examined to understand into which currency it would be converted. (For more discussion on redenomination issues, see Nordvig and Firoozye 2012.)

The threat of future crises

The tragedy of the Eurozone appears unavoidable, but it reflects far greater risks that will spread to Japan, the US, and other advanced economies.

Through our financial systems, we have created enormous, complex financial structures that can inflict tragic consequences with failure and yet are inherently difficult to regulate and control. We are at the behest of our politicians and financial sectors to prevent them from creating dangers. Yet around the world, our political and financial systems have aligned to build these dangers rather than suppress them.

The continuing crisis in the Eurozone merely buys times for Japan and the US. Investors are seeking refuge in these two countries only because the dangers are most imminent in the Eurozone. Will these countries take this time to fix their underlying fiscal and financial problems? That seems unlikely.

The lesson from all these troubles is clear: the relatively recent rise of the institutions of complex financial markets, around the world, has permitted the growth of large, unsustainable finance. We rely on our political systems to check these dangers, but instead the politicians naturally develop symbiotic relationships that encourage irresponsible growth.

The nature of ‘irresponsible growth’ is different in each country and region – but it is similarly unsustainable and it is still growing. There are more crises to come and they are likely to be worse than the last one.

Editor’s note: this piece first appeared in CentrePiece magazine (Centre for Economic Performance, LSE).

References

Boone, Peter and Simon Johnson (2010), “The Doomsday Cycle”, CentrePiece, 14:3.

Peter Boone and Simon Johnson (2011), “Europe on the Brink”, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Boone, Peter and Simon Johnson (2012), “The European Crisis Deepens”, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Igan, Deniz and Prachi Mishra (2011), “Three’s company: Wall Street, Capitol Hill, and K Street”, VoxEU.org, 11 August.

Nordvig, Jens and Nick Firoozye (2012), “Planning for an Orderly Break-up of the European Monetary Union”, submission to the Wolfson Economics Prize 2012, Nomura Securities.

Johnson, Simon and James Kwak (2012), White House Burning: The Founding Fathers, Our National Debt and Why It Matters To You, Pantheon.

Schularick, Moritz and Alan Taylor (2012), “Credit Booms Gone Bust: Monetary Policy, Leverage Cycles, and Financial Crises, 1870-2008”, American Economic Review, 102(2):1029-1061.

NOTE Lambert here. A question Johnson and Boone do not ask: Is there really such a thing as ‘responsible growth’? (How would we tell?) Some have argued not; see The Waning of the Modern Ages, from Links, yesterday.

“Is there really such a thing as ‘responsible growth’? (How would we tell?)”

There is no substitute for good judgement. For starters if real GDP is rising and real per capita income is falling, you would have to ask “what’s the point?. Fill up the petrie dish?”. Then of course there is the little issue of finite resources and environmental limits.

I would say the figure 2 in the Simon Johnson piece is grounds for a military coup.

I would say the entire “The Waning of the Modern Ages” article is a very weak on solutions – something he tries to blame on Naomi Klein – but I don’t think the talking heads here have a clue how far away we really are from energy/environmental solutions. But maybe he does. At the end of the article he almost sounds like an Austrian economist and creative destruction is the way we will go. Not to say that political gridlock won’t make that so.

I would say that the “The Waning of the Modern Ages” article was pretty upfront with “the solution,” although it’s not very comforting or one that anyone’s likely gonna want to hear:

To put it bluntly, the scale of change required cannot happen without a massive implosion of the current system. This was true at the end of the Roman Empire, it was true at the end of the Middle Ages, and it is true today.

And from Klein:

The only wild card is whether some countervailing popular movement will step up to provide a viable alternative to this grim future. That means not just an alternative set of policy proposals but an alternative worldview to rival the one at the heart of the ecological crisis—this time, embedded in interdependence rather than hyper-individualism, reciprocity rather than dominance, and cooperation rather than hierarchy.

I don’t see much ambiguity there at all. Pretty damn clear and concise, all in all.

Dear YouDon’tSay?;

I haven’t gotten around to reading the cited piece yet, but I remember the causes for the collapses of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, (can an Age collapse?) as being ecological mega shocks, a volcanic eruption in 535 AD for the Roman Empire [see: “Catastrophe” by Keys], and the Plague for the Middle Ages, [see, for instance “The White Company” by Doyle.] So, will we set off our own ecological mega shock this time? A few more Chernobyl style events might do nicely. Or, perhaps, something more sinister, like a collapse of industrial food production due to mismanagement of GMOs, [see “No Blade of Grass” by Cristopher.]

Too many of those supposedly ‘managing’ the worlds fate have lost their sense of proportion. I believe I can safely say that they suffer from hubris. That malady always ends in tragedy. Why the rest of us have to suffer along with them is the real mystery.

Well, I’m afraid the Roman empire collapsed 59 years before the volcanic eruption of 535 AD so the only possible causality mechanism would have to be the other way around.

Well, I will admit Berman is not exactly “a fresh spring breeze” in terms of what he has to say, and he doesn’t, as others have accused him of rightly, deliver a laundry list of goal-oriented solutions, but that’s all baked into the very message he’s delivering. Modern industrial capitalism (remember when those two words used to be routinely used together not all that long ago?) has run its course, and meaningful and effective solutions can no longer be generated from within its framework. In other words, the whole damn thing has to go! Modernism, techno-religiosity, capitalism, socialism, all of it! Pretty radical stuff, but I think Berman makes a pretty good case from what I’ve read from him (Why America Failed) so far. As I said, don’t accept that message to be widely embraced anytime soon, especially since the real honest to god fire breathing dragon in the room is the little matter of an ecologically unsustainable human population of 7B and rapidly counting, all of it only enabled by the “wonders” of rapacious modern global capitalism, although one could also well argue that the US is doing its part altruistically to limit that number through its numerous wars of global conquest (who’d a thunk?). When the prophets of old envisioned plagues of locusts on the land, one can only conclude that they must have been foreseeing the human population bomb. No doubt no politician – conservative, liberal, or otherwise – will ever get elected under the current system with the message that not only are current population levels unsustainable, but something on the order of 5 or 6 out of every 7 of us will need to “move on” and not be replaced (assuming we haven’t already thrown the climate into an unrecoverable tailspin) before it is. Now there’s a hard sell for ya!

You go first.

Any volunteers? Now that’s a harder sell?

“Modern industrial capitalism (remember when those two words used to be routinely used together not all that long ago?) has run its course”

I think the problem is that Berman no where says anything so simple as “‘modern industrial capitalism’ has run its course,” and what he does say is conceptually confused yet oracular and apocalyptic, a deliberately steaming rhetorical mess to match the climatological one he invokes at the outset.

If he had actually said that, he would have provided the “dead paradigm” that needs replacing, but he apparently has greater ambitions than that, only who can say what those are?

After all, he cites the Annales School to note that “capitalism” itself has its roots in the (preindustrial) 16th century, yet his oracular predictions dictate the demise of “capitalism” by 2100, due to climate change.

Then he quotes himself three or four times, a different book for each quote, in order to gripe about the “American dream,” defined in an overly narrow materialistic fashion, modern individualism, and the truck and barter in which he, as a public intellectual in a(n increasingly post-industrial) consumer society, himself engages.

If nothing else, I agree that he is not clear.

“If nothing else, I agree that he is not clear.”

Although if I really wanted to be mean, I would say that in this Halloween grab-bag of an article he comes across as having no real understanding of he wants to say, but that he’s really enjoying the opportunity to use Naomi Klein as a pretext for rehearsing his standard prejudices against the pecuniary interests of the unwashed masses.

I’ve never read his books, but when I encounter something he’s written on-line, that’s how he strikes me (which doesn’t exactly makes me want to read his books).

You go first. Any volunteers? Now that’s a harder sell?

Exactly. Tough message to sell. Therefore one that won’t be made. Although, if Berman is right, then reality will make it for us. Time will tell.

Well, it’s an even tougher message for Berman to sell because it seems like a pretext for his real business of deprecating the American masses and their “American Dream,” at least in the narrowly materialistic way that he understands it. (Which in itself is a little insulting, but whatever).

He exudes attitudinally more or less what Naomi Klein says the climate change denialists say global warming is– an attempt to materially disenfranchise the American masses (alongside their considerably wealthier bosses).

http://www.thenation.com/article/164497/capitalism-vs-climate?page=full

JT Faraday,

I agree with your assessment totally, and agree that Berman’s “attitude” definitely is more than a little off-putting at first blush. I guess I can only add that I admire Berman for making his points, which he greatly expounds upon in Why America Failed. Rest assured, if you didn’t like this small piece of Berman’s, you most definitely will not enjoy that book, abbreviated though it may be. I think it’s fair to say Berman is definitely not an “America First’er,” and he doesn’t pull any punches in saying so. Whether or not you agree with him is another matter altogether. I, for one, am one who respects that sort of chutzpah, especially when the facts on the ground back it up. You, on the other hand, will have to make up your own mind.

Well, like I said, I haven’t read it and as I currently have a lengthy and what is, for me, more thought provoking reading list, I have no plans to do so.

From what I can tell, however, he doesn’t really seem to be saying anything so earth shatteringly insightful as to warrant the press he gives himself in his own book titles.

For myself, it just kind of sticks in my craw that he condemns Americans as an entire “nation of ‘hustlers’,” when he’s so obviously a culture industry hustler himself.

“Oho!” said the pot to the kettle;

“You are dirty and ugly and black!

Sure no one would think you were metal,

Except when you’re given a crack.”

Not so! not so!” kettle said to the pot;

“‘Tis your own dirty image you see;

For I am so clean – without blemish or blot –

That your blackness is mirrored in me.”

— “Maxwell’s Elementary Grammar” (1904)

It’s even more entertaining to consider one of those press seeking book titles is “Dark Ages America.” Well yeah, no sh*t.

I guess I need to explain my paragraph to those not at least a little bit familiar with Austrian economics.

“At the end of the article he almost sounds like an Austrian economist and creative destruction is the way we will go. Not to say that political gridlock won’t make that so.”

“Creative destruction” is when the economy collapses, then someday – like a phoenix rising from the ashes – a new society emerges that has optimized itself for the new realities.

Austrians say that happens because the existing power structures (the elite) will not change and they attempt to preserve the status quo right up until the end.

Obviously this is not fun, and why we have Keynesians. But Keynesians are the preservers of the status quo. Catch 22.

‘ …the economy collapses, then someday – like a phoenix rising from the ashes – a new society emerges that has optimized itself for the new realities.’

This should be obvious, but has to be said.

On the rare occasions when I’ve had the opportunity to ask persons who went through Germany in the 1930s just what average Germans thought they were doing then in letting the Nazis take over, this is what those persons particular stressed — that the average German really thought Hitler et al. was going to make them and their society better.

” Why the rest of us have to suffer along with them is the real mystery.”

Debt based money system; and 40% of GDP is based on money creation from financial system. This money creation is not a real product.

You may enjoy a book by Ellen H. Brown, Web of Debt: the shocking truth bout our money system and how we can break free.

http://www.amazon.com/Web-Debt-Shocking-Truth-System/dp/0983330859/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1348399753&sr=1-1&keywords=web+of+debt

Memo to Lambert: one more unjustified moderation and I’m taking my contributions elsewhere.

I just have questions, not answers. Johnson and Boone work through the Peterson Instuite for International Economics, which is funded in part by Pete Peterson, the debt possed dude who wants to cut entitlements. These guys are also debt possessed. I would like to see a response from a Modern Money Theorist as to their assumptions about debt and the creation of money.

You’re right. Just check the following sentence:

“When the elderly finally demand their savings back in the form of pensions, the government will need to reduce its budget deficit of 8% of GDP and start running a sizeable budget surplus”.

Nope.

The elders just will just sell their bonds (a time deposit) for cash (a demand deposit). That is, swap a form of “savings” for another. And then spend them, thereby stimulating the economy.

The authors are just spreading the neoclassical obfuscations about money that have confused the debates on economic policies for so many years.

Sadly, their writing style indicates that they even believe in said obfuscations.

And now, back to reading the “Modern Money Primer” by Randy Wray.

My reaction exactly … they have no idea where debt comes from except for “savings”. In spite ofthe doom saying over Japan’s debt and demographics … collapse has yet to come, because Japan can create yen ad-infinitum! Just as the US can create dollars ad-infinitum, they can and they have! When can we demand the people lose their “professorships” for demonstarble intellectual incompetence?

MMT : Neoclassical = Dawn : Vampire.

When the orthodox economists can’t see any alternative other Than doomsday scenarios ,it is time to enter a new paradigm and change our monetary system……

I say we abandon these dismal failures they have wrought.the NEED act not only advances a move to end the profit taking of the financial sector out of our money creation,even more importantly it specifically allocates the money to go into productive endeavors,rather than speculative hocus pocus.It supports the money being spent into existence in ways that contribute to real goods production for the states and the people of this nation…..one point would be to implement beneficial renewable energy infrastructure…..people say,”yeah,but where will the money come from for these grandios ideas…..”…well ,from the money that goes back to treasury instead of being the bottom line of fed banks and there reckless behavior.

Screw the doomsday,screw the banks,screw Obama and Romney… And change the money system……

I second that.

The capital and middle class civil blob gets anxiety, and repeats the same mistake, every time it gets up late and has to pee, which is now every day.. labor points them to the restroom, and they feel better, until the next time. the macro is a function of the micro, a derivative in time. And the search for a global scapegoat presses on…

kevin,

So it’s labor that’s pointing me to the restroom every night (most nights several times!) these days is it? I’ll keep that in mind tonight.

———————–

The average Japanese woman today has 1.39 children, far fewer than is needed to replace the elderly. This means that the total population is set to decline by 26% by 2050.

———————–

Could you imagine the world problems that would be solved if the world as a whole voluntarily adopted the Japanese population growth rate? A 26% reduction in world population in 40 years, simply by not having babies, would certainly reduce the stress on the environment.

Unfortunately, the low Japanese birth rate is seen as a negative in economic terms.

I agree this is the single most important issue and it needs to be addressed head on. No mincing words. But we are all so instinctively averse to it, or our selflsh genes are averse to it. Just think, the rationale for every institution we have will have to be reversed. So, just a suggestion, a good place to start would be to legalize drugs.

As Morris Berman and many others correctly note, it will never be addressed until it’s too late. That’s just the fact of the matter. Better to deal with the facts than to continue wishful thinking pointlessly. The Japanese are an outlier and anomaly.

When the elderly finally demand their savings back in the form of pensions, the government will need to reduce its budget deficit of 8% of GDP and start running a sizeable budget surplus. Simon Johnson, Peter Boone

Why oh why is the myth that bondholders must be paid with tax revenues perpetuated? Budget surpluses by a monetary sovereign are stupid.

I’m surprised that the above quote got past Yves without an editorial comment.

Would have been nice to see the increase in Japan’s productivity on that graph.

Getting tired of this aging population meme. It wil be a problem when youth unemployment is at 1%.

Exactly. Why can’t the productivity advances symbiote with a declining birth rate? Could that not help save the system, at least in theory?

Perhaps well meaning but otherwise a ridiculously wrongheaded post. The authors seem to have no concept of fiat currency.

“through our financial systems, we have created enormous, complex financial structures that can inflict tragic consequences with failure and yet are inherently difficult to regulate and control”

Hello, who is this “we” they are talking about? It’s certainly not the 99%. Even when it comes to “policymakers”, i.e. the elites, the agency for all this is highly attentuated. They are described as complacent, not understanding the issues, at most complicit. Besides, it is all “inherently difficult to regulate and control.”

These are by no means the only weasel words used. There are a plethora of others:

“faulty”, “increasingly opaque”, “reckless”, “irresponsible”, “tragic”, etc.

What is missing from all these descriptions is the flatout criminality of our financial and political elites, indeed of our elites in general. The authors ask us not to believe our lying eyes, that it is an enormous accident that a financial system built by the rich and elites just happens to do such a bang up job of looting us in the 99% and transferring said loot back to these same rich and elites.

I agree with others that the authors’ analysis of the situation in Japan is lame. Assuming the primacy of money at best obfuscates, at worst enables looting. The real question should be whether or not the Japanese have the resources to take care of their future elderly. If they do, then the money is a secondary concern. It comes down simply to its proper distribution. If they do not, then no amount of money can fix the problem. The authors’ suggestion that the Japanese should raid the resources of other nations lands somewhere between obscene and bizarre.

I gave up reading Simon Johnson after 2 of his posts here. Because I could not follow his logic from premise to conclusion. And all the missing pieces in between… I got the feeling (which never betrays me) that he is a stealth propagandist.

Simon Johnson is just like Krugman in that they know where their last pay check came from. It was from folk that don’t want to challenge (hell, even talk about) the fundamentals of our class based social system with the global inherited rich owning/controlling everything.

Think about the folks that read this web site and still believe that the Fed is a public banking system….they walk among us.

Nationalize the Fed!!!!

I knew the MMT Tooth Faeries would show up, and if I believed the USG, in its current form,would use MMT to pay back the SS money they took from our paychecks, and nothing else, I would be a fan of MMT.

Can’t say I have much confidence in that one, so I think we had better get realistic and realize that we have a battle for finite financial resources shaping up.

P.S. Glad someone else noticed that Johnson gets published by the Peterson Institute. I always look for that too. But the Peterson Institute has been around a long while and grown very large, so I don’t think that Pete edits everything they publish. However, the PI is a cornerstone of Washington DC groupthink. But I would characterize Johnson as a mainstream conservative economist. And I thought it was a nice, easy to understand article, and Simon does know what fiat currency is, and considing the level of politness used in mainstream discourse, it was almost damning.

On the other hand. the Peterson Foundation was created in 2008, and that’s the one where Pete is “hands on”. They did the propoganda piece IOUUSA. And I’ve heard they are the ones astro turfing the Tea Party. Tho I’d believe Koch kicks in too.

Also, there is really nothing wrong with SS. It’s still positive (or missed slightly due to the great recession) on a cash flow basis for a few more years, then they need to pay back the trust fund which will last thru about 2035. That could be done by budget adjustments (defense?) or a small increase in progressive tax rates. They make a big deal about it needs to be “solvent” for 75 years(!?). A small adjustment in the payroll tax would do that. But believe it or not that is what they worry about.

What they worry about is protecting the real yields on their “corporate welfare”, US Treasury Debt?

Well, savers can buy a treasury bond fund too as one way to avoid a “Smith & Wesson Retirement Plan”.

I think the rich are concerned about having income from any source taxed.

If people need welfare it should be given to them honestly, not disguised as interest payments that the US Treasury has no need to pay.

I don’t know why you want to do away with the age old concept of working, saving some income, invest it somewhere safe for retirement – which might be loaning it to a credit worthy entity, and not being a “welfare recipient”.

People should be able to save risk-free but they are not entitled to a risk-free real return. If they want a real return then they should take real risks else they getting disguised welfare.

If people need welfare then give it to them honestly. We need to quit confusing welfare with finance.

Here you are buying the Goldman Sachs line – that investors come to them looking for risk [and finding it – my edit].

It wasn’t long ago that letting someone use your money, without significant default and inflation risk – say including food and energy – was worth something. Although not much – on the order of 2%-3%.

Investment, risk-free saving, and welfare should be distinct.

Buying a US Savings Bond is an investment America, and Uncle Sam is the wise steward deploying this capital to pursue the goals of our Great Nation:

Truth, Justice and The American Way – “Faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound”

Or maybe:

“Faster [to work] than a speeding bullet train, more powerful than Saddam’s Army, able to leap [from] tall buildings in a single bound”

F Beard:People should be able to save risk-free but they are not entitled to a risk-free real return. If they want a real return then they should take real risks else they getting disguised welfare.

Why not? Depends on how you measure things. Two reasonable ways of measuring things are (a) you should be able to get in the future about what you get now with your money – so riskfree return, at least zero interest (assuming zero inflation) or (b) you should be able to get in the future about what you gave now (your labor) to get the money.

In a sane MMT economy with a JG, a labor standard, savings bonds for small savers, with positive (real) interest lower than productivity growth, will have the effect of making one hour of labor now more equal to one hour of labor in the future. It could encourage saving, disinflation now, which could allow more investment, making thrift unparadoxical. That’s what happened with Savings Bonds during WWII.

Investment, risk-free saving, and welfare should be distinct. Not entirely possible.

Worshipping ZIRP, “printing money” is a common bugbear of MMT newbies. MMT is the system we have now. Printing money, printing bonds, who cares? There can be reasonable arguments for positive interest bonds, like Bert_S’s above, that don’t make the bond-saver/interest spender a welfare recipient.

That’s how SS once did & should operate. Why should retirees not enjoy the benefit of the enhanced productivity that their work created?

Printing money, printing bonds, who cares? Calgacus

I care. Should a rich saver get more “corporate welfare” (Bill Mitchell’s words) than a poor one? Or should welfare be reserved for only those who need it?

Why should retirees not enjoy the benefit of the enhanced productivity that their work created? Calgacus

Retirees will get the most from an optimum economy and an optimum economy does not give risk-free real returns.

If we are going to have an optimum economy then the bull-shit has to go. Money creation, instead of being one of the most deliberately confusing processes man engages in, should be straightforward and ethical.

Moreover, saving is not the Biblical ideal (cf. Matthew 25:14-30); investment is. People should be encouraged to invest, not save. And if they fail, then we should have a generous safety net.

Should a rich saver get more “corporate welfare” (Bill Mitchell’s words) than a poor one? Or should welfare be reserved for only those who need it?

On rich vs. poor savers see below.

Retirees will get the most from an optimum economy and an optimum economy does not give risk-free real returns.

Not at all clear if this is true, if one insists on measuring “risk-free real return” only in nominal, monetary terms.

Measuring the return, to some degree, in “hours worked” rather than “goods purchaseable”, allows retirees to reap productivity gains. Nothing wrong or unethical with that. Often, ideally, families, if the kids strike it rich, will help support their parents in a bit better fashion than if they hadn’t. I think that is a good, indeed ethical thing. Again, that’s how a good pay-at-most-as-you-go SS system works, like the sane pre1980s one.

Money doesn’t automatically inflate or not-inflate or deflate. Measuring these things, ensuring these things is not automatic & easy because they involve the simple (financial, monetary, abstract) interacting with the complicated (real goods, concrete). It takes human action to attain any real return, including zero. Doesn’t come about by magic. I’m just saying there are two legit ways of measuring “no real return”. What’s “welfare” & what’s “no real return” is not clear. If there’s a giant biblical catastrophe, negative returns for everyone might be in order – MUST happen for most.

Money creation, instead of being one of the most deliberately confusing processes man engages in, should be straightforward and ethical. Well, only part of it is the deliberately confusing nature of the process. An equally large part is confusing exposition.

People should be encouraged to invest, not save. That’s what I am saying. In a full employment economy, savings, savings bonds can encourage investment by making it less inflationary. WWII savings bonds / Bert_S’s / my arguments are nearly the only ones I’ve ever heard for positive interest. And I would support low or zero interest for financiers, high ones for small savers. That’s what was done during WWII, and it worked splendidly.

Perhaps this will make what I am saying more clear: Suppose everyone worked for the state at the same salary $1/hour and this never changed. People could save or spend as they wish. The state would ensure there is enough money to go around, simply by paying everyone. But if technology advanced & productivity improved, then prices could tend to fall – deflation. So savings could increase in value in reality, though not nominally. Would savers really be getting welfare because of this? Yes, there are a lot of problems with this; it’s just an illustration of my point. The savers’ money would be a little more like a common stock of the whole society. ;-)

In a full employment economy, savings, savings bonds can encourage investment by making it less inflationary. Calgacus

People should certainly be able to save fiat risk-free, at least in nominal terms. The monetary sovereign should provide that service (Whoever else?) and it should be free up to normal household limits. But it should certainly not pay interest (nor make loans for that matter).

And that fiat should neither lose nor gain purchasing power (0% real gain) but that of course is much more problematic since measuring real economic growth is very subjective. The way to get around this problem is to allow genuine private money alternatives good for private debts only. Then people could choose to use private currencies for private debts if they were unsatisfied with the performance of fiat. This would tend to make the monetary sovereign (at the insistence of its payees) very careful to preserve the purchasing power of its fiat.

So the reasonable expectation that one can save fiat risk-free even in real terms can and should be provided. But beyond that, if folks want real returns then they should take real risks. And if they fail, there should be a decent safety net.

The savers’ money would be a little more like a common stock of the whole society. ;-) Calgacus

Paying people not to consume seems perverse to to me; the future will not build itself and present consumption encourages real economic growth and technological advancement.

Also, usury should not be promoted by government. We need money forms that “share” wealth and power, not concentrate them. Killing the present money system will not be easy and like a weed it will tend to return unless we strike the root of it effectively.

A GAME WITH RULES

Interesting article, but let’s reinforce the fact that Europe has made progress in an area that remains just a dream in America. It is called the Golden Rule.

Part of the incessant politicking behind the “new, new financial architecture” supporting the Euro is a key element called the Golden Rule, by which national budgets are no longer allowed to exceed a slim percentage of their GDP. This rule existed in the Maastricht Treaty, but was blithely overlooked by the fat, dumb and happy EU Commissioners in Brussels. That mistake is (apparently) corrected.

That is, the Commission will have now the right to inspect National Budgets towards limiting the damages that “kicking the can down the road” can bring. Which means that self-indulgent politicians will not be allowed to pay for grandiose national projects with unlimited debt. (Thus getting their names inscribed on some eminently forgettable plaque posted in a public square.)

We’ve not yet got to that inflection point in our thinking and there is not even the slightest debate about capping National Budgets and perhaps getting a handle on the most notorious of its parts, the DoD expenditures for Corporate Welfare – aka the M-I-C.

Let’s also remember that Europe has never had a Glass-Steagall Act and Investment and Commercial Banking have always been found in the same banking entity. How did they ever avoid greedy finance Golden Boys from spinning sub-prime loans (resulting from a realty binge on cheap-credit) from tanking their economies?

There is and has never been such an animal as a “sub-prime loan”. Creditworthiness checks are fundamental criteria for any real-estate loan. And if one cannot show proof of one’s means, they just do not get the loan. This rule in important coupled with far less cronyism (aka the Revolving Door) between the Financiers and their national Regulatory Overseers.

The Old World and teach the New World a trick or two? Evidently … particularly when the latter shows signs of deliberate oversight laxity as Consummate Greed overtakes its Golden Boys ‘n Girls.

European finance is a game with rules and sharp-eyed game referees. America needs to establish the same.