By The Unknown Transcriber

Lambert here: The Unknown Transcriber has done a superlative job transcribing this important talk [applause]. I especially like how Lessig contextualizes Swartz’s death as a consequence of corruption. It’s all about the rents, baby! Section I will be published today; Section II will be published tomorrow.

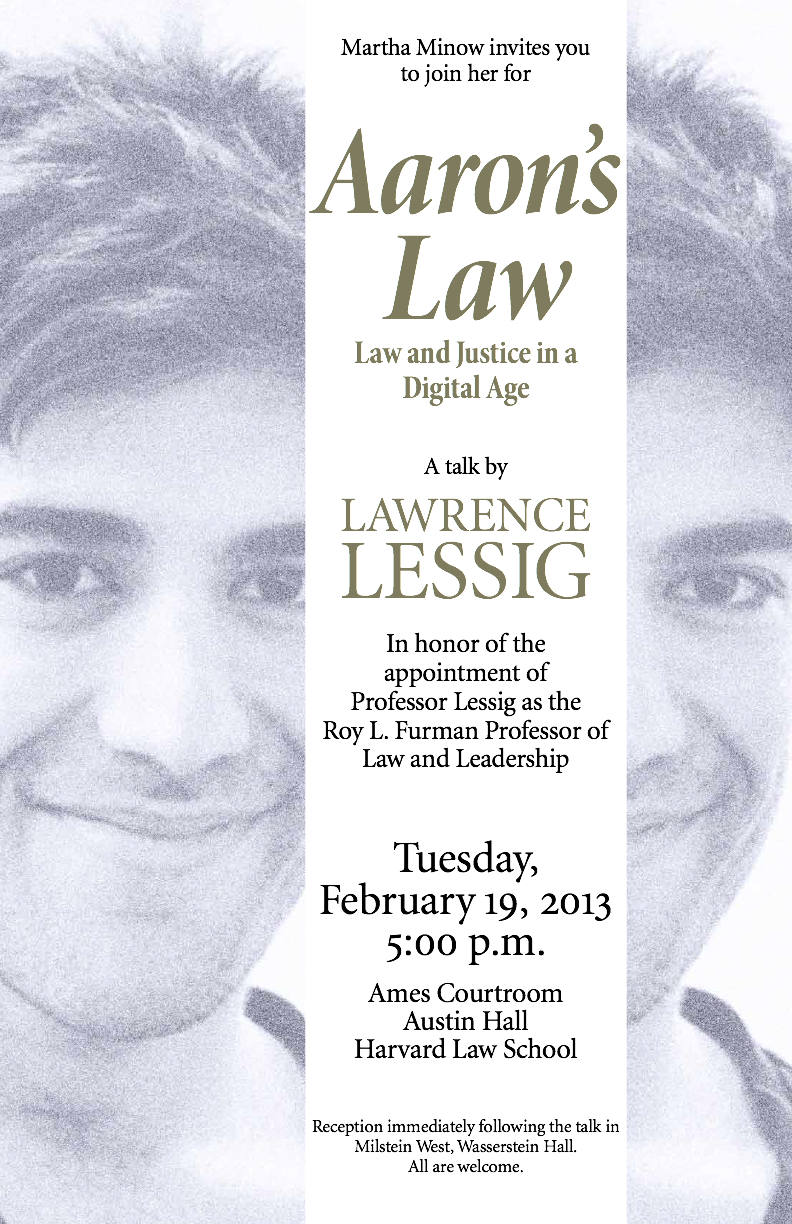

This is the full transcript of “Aaron’s Laws” talk given by Lawrence Lessig at Harvard on February 19. A good summary of the talk, by Harvard second-year law student Eric Rice, is here.

Outline of talk:

NOTE: Lessig numbers the parts of his presentation on slides like this: <1> is Part I. These slides are embedded as thumbnails in the transcript.

Section I:

Intro

Part 1: Aaron

Part 2: Aaron’s works – B©, ©, A©

Part 3: As a citizen

Part 4: The “crime”Section II:

Part 5: Godzilla meets Jefferson and Thoreau

Part 6: Aaron’s laws

Closing: Aaron and usAudience Q&A

1. The arrest, MIT and Secret Service, and Abelson report?

2. What to do about prosecutorial overreach, especially for those who don’t have Aaron’s connections?

3. Easy for lawyers to make things worse, how to make things better?

4. MIT Office of General Counsel running things, not educators? Lawyers huge part of the problem?

5. Aaron’s third law – how to clean up campaign financing?

Part I:

Lessig begins at about 8:50.

Clicking on the centered images of Lessig’s slides below should take you to that spot in the YouTube.

Transcript

Lawrence Lessig: Thank you, Martha, and from a distance thank you, Roy L. Furman, for the honor of being able to celebrate the incredible mix of talent in business and in art, but I’m sorry to have to celebrate that mix in the subject that I’m going to address tonight. Because when I was planning this talk, it was not to be a talk about Aaron Swartz. I’ve been working for many years in the field of corruption. This talk was to be a step forward in that work, but when five weeks and four days ago Aaron took his life I realized that the tumult of that experience would distract me and I asked Martha to let me delay the talk. And then I asked her to let me talk about Aaron. These plans that were canceled evolved to a plan to talk about what we call Aaron’s Law.

But I need to mark this conversation by recognizing how inappropriate it is. Because these sorts of talks are to be academic. There’s nothing academic about my connection to this subject. I can’t promise the disinterestedness that is so crucial to the contribution that we as academics are to make. I can’t even promise expertise, as this topic will force me into areas that are not my expertise. I can only approach this topic tonight not as an academic but as a citizen and a friend who believes it is also completely not appropriate that we have been brought to this place five weeks and four days since Aaron took his life.

Aaron Swartz was a friend. He was a colleague. He was a co-conspirator. He lived for 26 years. Half of those 26 years he lived his life in public. He was a prodigy. At the age of 13 he was awarded the ArsDigita prize – there he is accepting the prize – for work that would eventually inspire things like Wikipedia. At the age of 14 he helped co-design the RSS protocol – there is his co-designer Dave Winer. At the age of 15 he was the core architect for the technical infrastructure for Creative Commons. Here he is launching that technical infrastructure:

Aaron: Now that you’ve seen the theory behind Creative Commons, it’s time to show you some of the practice. So when you come to our website here, you will go to Choose License. It gives you this list of options and explains what it means, and you fill out three simple questions. Do you want to require attribution? Do you want to allow commercial uses of your work? And do you want to allow modifications of your work?

At the age of 17, after being home schooled, he came to Stanford. He lasted for just about a year. At the age of 19 he began Infogami, which eventually merged with Reddit and became the most popular crowdsourced news site on the web today. And from the age of 20 through the end, he worked in a series of incredible projects, from the Open Library project to the Public.Resource.Org project to Change Congress, which I helped start with him. He was on our board, migrated to Fix Congress First and Rootstrikers, to the Sunlight Foundation, to the PCCC, and his final organization, Demand Progress. Twenty-six years.

In 12 of those years, I had the honor of knowing him. I first met him at conferences. His parents would chaperone him as a 12 or 13-year-old to attend these computer conferences. I invited him to be the core architect of Creative Commons. I got to watch him grow up. It was the first experience of being a father, although of course I can’t claim any responsibility for who he was. But who he was is captured still for us in his writings, his writings that live on the web. You can still find at the Archive.org the blog he had on his first day at Stanford which described who he was, what he was doing, what he dreamed of. You can’t see his picture – you see that little lack-of-picture icon. If you look at the code for the website, you can see his description of the picture. The short description is “My hat, my face, half in shadow, from a bright light towards the upper right,” but the longdesc, long description, is “A young man with a detached look and half smile stares at you with a quizzical look. There’s a bright light coming from an upper left casting part of his face in shadows. He seems to be wearing a black shirt which blends in nicely with the solid black background.”

Here’s who he announced to his fellow students he was. He said, “I think deeply about things and I want others to do likewise. I work for ideas and learn from people. I don’t like excluding people. I’m a perfectionist, but I won’t let that get in the way of publication. Except for education and entertainment, I’m not going to waste my time on things that won’t have impact. I try to be friends with everyone, but I hate it when you don’t take me seriously. I don’t hold grudges, it’s not productive, but I learn from my experience. I want to make the world a better place.” That was that kid.

And in his early blog at Stanford University, he displayed his character as the most insightful kid I’d ever known. His first day at Stanford he blogged, “Afterwards, we go over the dos and don’ts of campus life.” These are the Stanford officials describing to him how he’s supposed to live as a student. “You know, things like smoke your pot over by the lake, keep your vomit from binge drinking off the floor, and never, ever share files over the Internet.” [audience laughter]

Or “Stanford: Day 58: Kat and Vicky want to know why I eat breakfast alone reading a book, instead of talking to them. I explain to them that however nice and interesting they are, the book is written by an intelligent expert and filled with novel facts. They explain to me that not sitting with someone you know is a major social faux pas and not having a need to talk to people is just downright abnormal. I patiently suggest that it is perhaps they who are abnormal. After all, I can talk to people if I like but they are unable to be alone. They patiently suggest that I am being offensive and best watch myself if I don’t want to alienate the few remaining people who still talk to me.”

My favorite, two years later: “I’ve decided to stop being embarrassed. I’m saying goodbye to the whole thing: that growing suspicion as the moment approaches, that sense of realization when it comes, that rush of blood reddening your cheeks, that brief but powerful desire to jump out of your skin, and then finally that attempt big fake smile trying to cover it all. Sure it was fun, but I think it’s outlived its usefulness. It’s time for embarrassment to go.”

This is who he was. He was a kid. He was a man. He was a mensch. He touched tens of thousands, he has inspired millions, and in the time I have here tonight, I want to describe how I think we need to honor him.

Now if you think of this range of organizations that he was part of, this is a wide range of ideas. But to add a flavor of academics to this talk, let’s think about the periodization of these ideas. And I think there are three.

There’s a first stage we could think of as the Before Copyright stage, where what he was working on was projects to make information more widely available – RSS and his work with Tim Berners-Lee at the W3C founding the RDF project. This is the B Copyright stage, before copyright.

And then the second stage is the work around copyright – Creative Commons, the Open Library project, the Public.Resource.Org work – this was trying to make legal and appropriate the information that was being shared across the Internet.

And then finally, the After C stage, the after copyright stage of his life, when it wasn’t just copyright, but it was social justice and the issues around making the world a better place that was the focus of his attention.

But at the center of this and the center of the struggle that brought him to his end was copyright. And in the debate between those who are pro and anti copyright, Aaron Swartz was on neither side.

Indeed, if you remember the president’s speech when he was a candidate for Senate and he said, “I don’t oppose all wars. What I am opposed to is a dumb war,” I think Aaron could have said, “I don’t oppose all copyright. I opposed dumb copyright.” Dumb copyright. Copyright that doesn’t serve copyright’s purpose.

So, for example, think about this database, the PACER database, a database that has public documents about federal court proceedings, a database that makes itself available to the public, at the time Aaron was involved in this project at 8 cents a page, begging the obvious question in the digital age, what is a “page”? But this project to make this work available, this uncopyrighted government data available, obviously imposed significant burdens on those who didn’t have the money necessary to get access to this information, so Aaron and his co-conspirator, Carl Malamud of Public.Resource.Org, decided they would liberate the PACER database. They would liberate it by building a script that would suck down the information from the database to a computer and then clean the data up and make it available on the web.

Did that violate any copyright? No. There was no copyright in this data.

Did it violate the terms of service? Turned out it didn’t. There was an explicit permission to get access to the database that they took advantage of with the script.

Did it violate any of the technical protections that were built up around this database? It did not. There were no technical protections once you got access through the permissions granted through the terms of service. It was simply a script to access more quickly things people had the right to access.

It was a loop hole, a loophole, the sort of thing we have lobbyists for, finding loopholes in all of our laws, the sort of reason we have tax lawyers, finding loopholes in our obligation to pay taxes. But this was not a loophole for private gain, this was exploiting a loophole for public gain. Against restrictions that were not serving a public interest.

Here’s a second example. The United States Copyright Office has a database of all their copyrights and they have a technology to permit you to search that database. This is a technical legal term, but that database sucks. [audience laughter] So Aaron and Carl decided they wanted to engage in a similar liberation project. This time Carl went to the Library of Congress and, using permission given to him at the Library of Congress, snarfed all this down using a script to their computer and then cleaned this data up and made it accessible to a whole bunch of library projects that needed this information. Did it violate any copyright? It did not. Did it violate any terms of service? It did not. Did it violate any technical protections? It did not. They once again took advantage of this loophole, an unexpected use to access this public data.

Now in both cases the critical thing to see is that the databases that Aaron was archiving were not the Sony Picture Archive database, it was not the Universal Music Group database, this was not an effort to liberate all culture and make it all free on the Internet – these were targets where the restrictions made no sense. They made no copyright sense. And so he used his knowledge to evade them.

And it’s critical to see the reactions to these invasions. So when the PACER project became publicly known, the government sent the FBI to investigate Aaron, literally an FBI agent sitting outside of his home monitoring him and following him, this potential terrorist, Aaron was. But the Copyright Office’s response was edifyingly different. Marybeth Peters wrote a letter in response to an inquiry where she said, “There is no copyright protection in these records – they are in the public domain…The database of the online records is likewise in the public domain.” It was completely appropriate for Aaron to do what Aaron had done, because these restrictions were not serving any copyright purpose. These were instances, I want to suggest, of unproblematic hacking.

Hacking. Though it’s not popular, it’s not appropriate, especially not appropriate in a law school to say this, but we need to celebrate the activity of hacking. We need to celebrate it because like lawyers, maybe better than lawyers, what this hacking is is the use of technical knowledge to advance a public good. Use of technical knowledge to advance a public good. There is cracking, there is violating people’s rights, there is doing things that hurt people – that should not be celebrated either when done with the law or through code – but hacking, using technical knowledge to advance the public good, is something that we lawyers too should celebrate just as hackers do.

So Aaron was a hacker. But he was not just a hacker. He was an Internet activist, but not just an Internet activist. Indeed, the most important part of Aaron’s life is the part most run over too quickly – the last chunk, when he shifted his focus from this effort to advance freedom in the space of copyright, to an effort to advance freedom and social justice more generally.

And I shared this shift with him. In June of 2007 I too announced I was giving up my work on Internet and copyright to work in this area of corruption. And I’m not sure when for him this change made sense, but I’m fairly sure when it made sense for me. Happened in 2006. Aaron had come to a conference, the C3 conference, the 23rd C3 conference in Berlin, and I was with my family at the American Academy in Berlin and Aaron came to visit me. And we had a long conversation, and in the course of that conversation Aaron said to me, how are you ever going to make progress in the areas that I was working on, copyright reform, Internet regulation reform, so long as there is, as he put it, this, quote, “corruption” in the political field. I tried to deflect him a bit. I said, “Look, that’s not my field.” Not my field. And he said, “I get it. As an academic, you mean?” And I said, “Yes, as an academic, that’s not my field.” And he said, “And as a citizen, is it your field?” As a citizen is it your field?

And this was his power. Amazing, unpatented power. Like the very best teachers, he taught by asking. Like the most effective leaders, his questions were on a path, his path. They coerced you, if you wanted to be as he was. They forced you to think of who you were and what you believed in and decide, were you to be the person you thought you were? So when people refer to me as Aaron Swartz’s mentor, they have it exactly backwards. Aaron was my mentor. He taught me, he pushed me, he led me. He led me to where I work today.

Now at first after this shift, his shift and my shift, we worked together. He was a board member of Change Congress and Fix Congress First. He was a supporter of Rootstrikers. But later, having become impatient and discouraged with the way this work was happening, he moved more in the direction of social justice that Demand Progress pushed. So our paths diverged. He was working on the project of trying to push Barack Obama to the left, or I think trying to turn Barack Obama into Elizabeth Warren [audience laughter]. Me, my project was simply to try to get this man [Obama slide] to take up that fight which on April 2, 2008 he promised the fight to change the way Washington works because as he told us, “If we’re not willing to take up that fight, then real change – change that will make a lasting difference in the lives of ordinary Americans – will keep getting blocked by the defenders of the status quo.” That was my fight. And I teased him mercilessly that he had given up the real fight because of the temptation of list building and girls, I think was really what was behind it. And I believed eventually he would return to this core fight because I think he saw, because he said this core fight was ultimately the fight we had to win.

Now, such change, such change in your personal work and the thing you’re going to be doing, it turns out to to be pretty hard. When I did it I was told by a colleague I had betrayed the Internet. He was condemned to be an Internet activist forever in the eyes of most people. People never quite believe that you really want to move beyond the coolness of tech conferences and talk about copyright. And indeed, September 2010, Aaron confronted this again – and I’ll give you a couple clips from his very last public speech at Freedom to Connect. This is the way it begins.

[video clip, Freedom to Connect keynote address, May 21, 2012]

Aaron: So for me, it all started with a phone call. It was September, not last year, but the year before that, September 2010, and I got a phone call from my friend Peter. “Aaron,” he said, “there’s an amazing bill that you have to take a look at.”“Well, what is it?” I said.

“It’s called COICA, the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeiting Act.”

“Oh, Peter,” I said, “I don’t care about copyright law. Maybe you’re right, maybe Hollywood is right, but either way, what’s the big deal? I’m not going to waste my life fighting over a little issue like copyright. Health care! Financial reform! Those are the issues that I work on. Not something obscure like copyright law.”

Now, Aaron here was having a kind of Al Pacino moment.

[Godfather III clip]

Michael Corleone: Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.

[audience laughter]

But after he got over this feeling that maybe he needed to think about this a little bit more, he began to become convinced this was an issue he should work on. He wrote me an e-mail. He said, “I’m planning a campaign against this crazy new COICA bill tomorrow.” He asked me to sign his petition. And I had my own not quite Al Pacino moment, more George Costanza moment –

[Seinfeld clip]

George Costanza: Every time I think I’m out, they pull me back in.

– and I ignored him, because I thought it was outrageous he would ask me to get back involved in a copyright fight. So a couple days later, after me not even responding, he wrote me, “Any idea if Lofgren” – Congresswoman Lofgren – “or anyone else you can think of for that matter, would be willing to take a stand against COICA?” And, playing dumb, I responded, “What, is that a virus?” And he responded, “No, the Internet censorship bill, close enough.” And indeed there was this bill, COICA. And what COICA did was this extraordinary provision to give the government the power to bring an in rem action against a domain name. So if somebody complained that they thought there was copyright infringement happening at harvard.edu, you could bring an action and the Attorney General could get someone to turn off harvard.edu because of this allegation of violation of copyright law.

So Demand Progress and others began a concerted fight against this proposal, and it looked pretty hopeless originally because there was a unanimous vote in favor of this provision in the Senate Judiciary Committee. But it never got to the Senate floor, because of this emerging fight. And that itself was a victory. And then pretty quickly this, like Jason in Friday the Thirteenth, came back, and he realized it wasn’t quite over yet, this bill had migrated and become what we now think of as the SOPA/PIPA legislation, and there was a new fight in its new instantiation to stop Congress from passing this bill. And one of the most important leaders in that fight was Senator Wyden, who had a filibuster where part of his filibuster was reading the names of every single Internet activist who contacted him saying that they supported the fight against SOPA and PIPA. And eventually there was a huge victory when in the House they voted down the bill. And then there was a break for Christmas. People thought it would come back. But then after major sites went dark in January, there was a total victory as the Senate signaled it would not bring the bill up either. And here’s Aaron on the victory:

Aaron: And that was when, as hard as it was for me to believe, after all this, we had won. The thing that everyone said was impossible, that some of the biggest companies in the world had written off as kind of a pipe dream, had happened. We did it. We won. And then we started rubbing it in. You all know what happened next. Wikipedia went black, Reddit went black, Craigslist went black, the phone lines on Capitol Hill flat out melted, members of Congress started rushing to issue statements retracting their support for the bill that they were promoting just a couple days ago. And it was just ridiculous. I mean, there’s a chart from the time that captures it pretty well. It says something like January 14th on one side and has this big long list of names supporting the bill, and then just a few lonely people opposing it. And then on the other side it says January 15th. And now it’s totally reversed. Everyone is opposed to it, just a few lonely names still hanging on in support.

This was a victory, but the thing he saw that I didn’t see at the time was that it was not just a victory for copyright. He described [talking to] Senator Schumer, Wyden was saying, he said, “‘What we’ve seen over the last few weeks from the grassroots is a time for the history books.’ The win is a triumph over very powerful special interests.” And what that triumph produced was a recognition that there was a more fundamental issue here, the issue that he and I had originally bonded on, this issue of corruption. But even more importantly was this interesting political reality that this fight had demonstrated.

Aaron: Now I’ve told this as a personal story partly because I think big stories like this one are just more interesting at human scale. The director J.D. Walsh says good stories should be like the poster for Transformers. There’s a huge evil robot on the left side of the poster and a huge big army on the right side of the poster, and then in the middle at the bottom there’s just a small family trapped in the middle. Big stories need human stakes. But mostly it’s a personal story because I didn’t have time to research any other part of it.But that’s kind of the point. We won this fight because everyone made themselves the hero of their own story. Everyone took it as their job to save this crucial freedom. They threw themselves into it. They did whatever they could think of to do. They didn’t stop to ask anyone for permission. You remember how Hacker News readers spontaneously organized this boycott of Go Daddy over their support of SOPA? Nobody told them they could do that. A few people even thought it was a bad idea. It didn’t matter. The senators were right. The Internet really is out of control.

So this was victory, total victory, and it was his. His last moment to reflect on it. And as you can see, anyone who knows him well, in his look, in his face as they celebrate this speech, which turns out to be his last speech, it was a moment when he could reflect that he had done something and believed he had done something important.

Now, that was shortly after he turned 25. A year before that, almost at exactly the same moment, it was not as happy, because a year before that he was arrested. He was arrested at MIT, he was arrested in this building at MIT [photo], building #16 [map], for entering the server. The government charged what he had done was to break into a restricted computer wiring closet at MIT. He broke in in the sense that he turned the door handle – it was unlocked. He had accessed MIT’s network without authorization. Of course, MIT has an open network. Anybody is free to access the network who visits MIT. He had connected to JSTOR’s archive of digitized journal articles. True, and as a Harvard fellow at the time, he was entitled to access the JSTOR archive of digitized articles. He had used that access to download a major portion of JSTOR’s archive. Here is the legal question. And he had avoided MIT and JSTOR’s effort to prevent this massive copying, and finally he had eluded detection and identification. For you to see how much of a genius he is, here was his technique of eluding detection [surveillance photo of Aaron holding up bicycle helmet]. [audience laughter]

The database he was accessing was JSTOR. JSTOR was started in 1995. It’s a nonprofit organization. The Mellon Foundation started it. It is huge, extraordinary archive of academic articles from the beginning of time when academic articles were published. When it was launched, people thought it was brilliant. The access that it provided to this information was extraordinary. But increasingly JSTOR had been subject to criticism. Carl Malamud of Public.Resource.Org called it “morally offensive, $20 for a six-page article unless you happen to work at a fancy school.”

So, for example, to get a sense of this point, I did a demonstration. I was struck by this article in the Harvard Gazette talking about Gita Gopinath’s time at Harvard, her new arrival at Harvard, and the writer of the article I guess ran out of questions so he noticed that there are not many books on her shelf. And he asked her why. And her response was, “Everything I need is on the Internet now.” Everything I need is on the Internet now. So consider what exactly that means. If you look at a subject that I focus my attention on now, corruption, and you go to Google Scholar and you ask for the top articles about corruption, campaign finance, and you go through the top 10 articles in campaign finance and try to access them on a computer not on the Harvard network, this is what you find:

The top article, you can get for $29.95.

Number 2, you can get through JSTOR, terms unspecified.

3. $29.95.

4. Free so long as you agree to a $99.95 yearly subscription.

5. JSTOR, terms unspecified.

6. JSTOR, $10 for the article.

7. JSTOR, terms unspecified.

8. JSTOR, terms unspecified.

9. JSTOR, terms unspecified.

10. $29.95.

So how accessible is this information to those not at an institution like this? Well, one of them is free for one time only, one of them $10, three of them $29.95, five terms unknown, protected by JSTOR. So when she says everything is on the Internet now, what does that mean? It means if – and this is a big if – tenured professor at elite university, or maybe a professor at elite university, or student or professor at elite university, or students or professor at U.S. universities – whatever, if you are a member of the knowledge elite, then you have free access. But the rest of the world, not so much.

Now, we should name this. We should name it “outrageous.” Here’s Hillary Clinton giving it that name. We should name it outrageous because we built this world. We academics built this world. It flows from the deployment of copyright that we have chosen. But here copyright is not to benefit authors, it’s to benefit publishers. It’s not to enable authors – there’s not one of the authors on this list who get money from copyright. Not one wants the distribution of their article limited. Not one of them has a business model that benefits from restriction. Not one of them should support this system as knowledge policy for the creators here. It is crazy. It is dumb copyright policy. And as Aaron would say, he doesn’t oppose copyright, he opposed dumb copyright.

Now the thing that I didn’t see was just how profoundly this troubled him. Noam Schieber has the fantastic piece in New Republic which recounts Aaron attending a 2008 conference in Italy. Quotes, “Rich people pay huge amounts of money to access articles. But what about the researcher in Accra? Dar es Salaam? Cambodia? It genuinely opened his eyes.” And I hadn’t, until this talk, put these things together to recognize that it was after his attending that conference that he wrote anonymously, although the contact e-mail was his e-mail so it wasn’t so anonymous, The Guerilla Open Access Manifesto.

The Guerilla Open Access Manifesto has a lot to it, but here’s the part I want you to focus on. He says, “Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. The world’s entire scientific and cultural heritage, published over centuries in books and journals, is increasingly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private corporations.” He talked about open access, the choice authors now make to make their work freely available. But he said open access “will only apply to things published in the future. Everything up until now will have been lost. That is too high a price to pay. Forcing academics to pay money to read the work of their colleagues? Scanning entire libraries but only allowing the folks at Google to read them? Providing scientific articles to those at elite universities in the First World, but not to children in the Global South? It’s outrageous and unacceptable.” And, “we can fight back.”

“We need to take information, wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world. … We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks. We need to fight for Guerilla Open Access.”

And that manifesto linked to a site, and that site linked to a bunch of projects that encouraged people to scan and share what they had scanned, to send Aaron hard disks or journal articles, PDF forms, and they would help to make them available.

Two years later he attended a conference, this time in Budapest, where this issue came up again, and at that conference I am told he learned that JSTOR had been asked, “How much would it cost to make this available to the whole world. What would we have to pay you?” And the answer was 250 million dollars. 250 million dollars. And it’s immediately after that conference that it’s clear Aaron begins the actual work that brought him into the crosshairs of the government. And here he is talking about this shortly after that conference:

[video clip, The Social Responsibility of Computer Science, University of Illinois, October 16, 2010]

Aaron: Everything up to now, all of those journals, all that scientific legacy going back to the Englightenment, that’s still behind locked gates. But you, you have a key to those gates. And, with a little bit of shell script magic, you can get those journal articles. You can download copies of them, and once you have a copy, theoretically you could make it available to everyone. And if you don’t know how to make it available to everyone without getting caught, you can go to GuerillaOpenAccess.com and find my mailing address. And hard drives that get to us there will find their way online. Feel free to visit the website using Tor if you want to protect your anonymity. Same goes for any other caches that you guys may have that need to find a gentle home, scanned books perhaps.I mean, you know, this isn’t the biggest problem in the world, but like I think we should understand, this is a serious problem. In the same way that people did civil disobedience, broke the rules for the civil rights movement, there are people who now chain themselves to nuclear power plants to prevent the earth from imploding. Like, it’s actually a serious problem that the vast majority of the planet doesn’t have access to our accumulated scientific knowledge. And I think it might be a worth a little bit of shell scripting and breaking a couple rules to solve that problem.

“Shell scripting and breaking a couple rules.” Now, Aaron never spoke to me about this plan, shell scripting and breaking a couple rules. In my view, which he knew, the issue is much more complicated. Not the copyright issue, I’m completely with him on that. The what-to-do-about-it issue. In my view, organizing to force change was fine, but I was not so clear on what he was calling civil disobedience. I was not so clear because the facts here are special.

First of all, a fact that was not even clear to me at first was that JSTOR doesn’t even set its own prices. When you go to an article and you’re outraged by the fact that it costs $20 to get an eight-page article, that’s because the journal itself had set that price. And for all of its flaws, JSTOR did actually facilitate real access that wasn’t there before. Certainly, as a percentage, the number of have nots after JSTOR is exactly the same. But as a percentage, the haves are many, many more, as many universities that never would have had access to this information have it because of the structure JSTOR had built.

But the most important point, the point I had written about, was to take this on through civil disobedience risked devastating penalties.

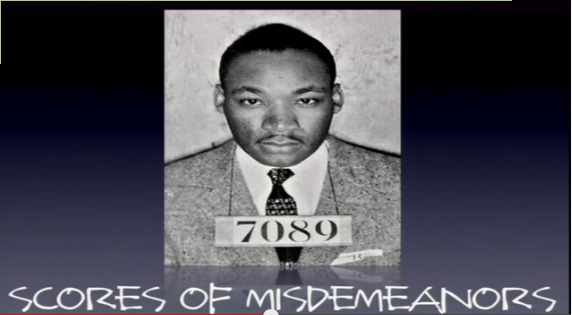

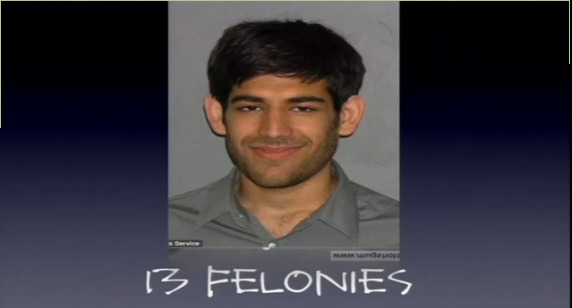

Civil disobedience has an important tradition. David Byrne wrote a piece about Aaron and civil disobedience where he reflects on the instances of civil disobedience on the past. This in particular you think of as our most important civil disobedient of the 20th Century:

What is civil disobedience about? It’s about taking a public act, being willing to pay the penalty because you are able to pay the penalty. But copyright is different. The disobedience in copyright is not done in public. People are not willing to pay the penalty because we are not able to pay the penalty.

Compare: Martin Luther King, the civil disobedient, was arrested on scores of misdemeanors. He was only ever charged with two felonies and acquitted by an all-white jury of those two felonies because the basis for the claims were so outrageous. He did jail time, scores of days in jail. Compare him with Aaron, charged with 13 felonies, giving a federal judge the right to sentence him to up to 35 years in jail.

Now, he knew this about my view. So the alleged “crime” he engaged in while he was a fellow here at Harvard was not engaged in at Harvard. To protect me, I take it, he went down the street to MIT to commit what is called the crime.

So how do we understand what he did? Let’s start simply. Let’s start in a very conservative space. What he did is not obviously legal. But is it obviously illegal? And the answer to that depends on what we think he was doing. And there’s a range of possibilities. I’m going to be obscure because I actually know what he was doing but I can’t reveal that in the context of this context because I learned it in the context of representing him for a brief time, so I will give you a range and you can pick what you think is possible.

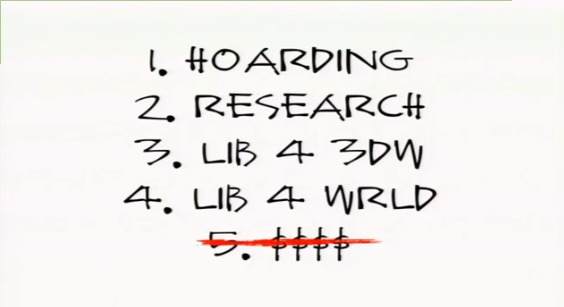

Number one, he could have been simply hoarding this material. Geeks have been known to do stuff like that. “Let’s just get everything, so it’s all on my machine.”

Number two, it could have been research. When he was at Stanford, he worked with this Stanford law student [Stanford Law Review December 2008, Shireen Barday: Punitive Damages, Remunerated Research, and the Legal Profession] on a project to evaluate the corruption in legal scholarship. And what he did with this project with this woman was to download all of the journal articles from Westlaw using one of his shell scripts and then to read through the first three footnotes of those articles to identify funding sources for all of those articles, and then use that information to try to evaluate whether the funding source might have been related to the actual conclusion of the article. None of the material was made available outside of Westlaw, so none of it was distributed. It was just solely for the purpose of doing this evaluation of the integrity of legal scholarship.

Number three: He could have been intending to liberate the work for the Third World. That was the point that Noam’s piece brings to the fore.

Number four: He could have been intending to liberate it for the whole world. That at least is the sense of the Guerilla Open Access movement.

And number five: In theory at least he could have been trying to make a lot of money, because if it was worth 250 million dollars to JSTOR, what could he have gotten for it on the black market now? [audience laughter] As much as we academics think of ourselves, none of us think that our articles are worth squat on the black or white market, so let’s just wipe this one off the possible list of what Aaron might have been doing and focus on the other four.

How could doing any of these four things be wrong, or what kind of wrong could it be? I’m going to focus on two. One is copyright and the other is the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

So, copyright first. JSTOR, of course, has a database of works. Some of those are copyrighted, and the act of “copying” those works you might think is obviously regulated by the law of copyright. That’s what the word is, “copy right.” Obviously, but obviously false. Because of course the history of copyright law has not been a history of regulating copies. The first copyright statute regulated printing, reprinting and publishing. The word “copy” only enters our statute in 1909 when it gets appended to the traditional list, “copy,” but according at least to Lyman Ray Patterson it was something of a typo, it was a mistake, because the word “copy” is what you use to refer to what you did with a statue, it’s not what you would use to refer to what you did with a book, which means this was an accidental addition. But once the word was in the statute, it took on its own life, as technology encouraged ways for people to, quote, “copy.” Which means that each of these activities, regardless of their ultimate effect on the underlying business model of the entity that was being copied from, triggers copyright law because they produce a copy.

But interestingly, if you look at the indictment and in the superceding indictment, neither of them charge copyright infringement. Didn’t even mention copyright.

So why is that? Well, one, it might have been harder. Many of these articles were in the public domain. Others were in private domain. Proving all that would have complicated the matter. But I think the real reason is number two, JSTOR very quickly signaled to the government they didn’t want to have anything to do with this case. They did not believe it should be prosecuted. They were not going to cooperate, and they would have had to cooperate to make it compelling for them to have the copyright case they would have had to pursue.

So if it wasn’t copyright, then it was the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, a statute from the 1980s which is long and complicated but has two critical parts. One which criminalizes accessing a computer system without authorization, and the other which criminalizes exceeding the authorized access the system is giving you.

So without authorization, that means stuff like stealing a password or using technology like this [Automated password guesser Python script] to go and hack into a system by guessing a password. “Exceeding authorization” though created a puzzle in the courts. What did that mean? Did it mean “hacking” or simply “misusing” the data relative to the terms of service that the provider offered?

A very important case from the Ninth Circuit tries to resolve that question. Judge Kozinski in this case sets up two different cases. He says [U.S. v. Nosal, 9th Cir. 2012 PDF] “assume an employee is permitted to access only product information on the company’s computer but accesses customer data: He would ‘exceed[ ] authorized access’ if he looks at the customer’s list” through “hacking,” and by hacking he meant, as he specifies at the end of the opinion, “the circumvention of technical access barriers.” He distinguishes that case from a second: “the language could refer to someone who has unrestricted physical access to a computer, but is limited in the use to which he can put the information. For example, an employee may be authorized to access customer lists in order to do his job but not to send them to a competitor.”

Now this is a different sort of restriction between these two kinds of unauthorized access. One is a restriction of code, the other is a restriction of law.

With the first one, “hacking,” you break code restrictions in order to get access to the under– or to use the underlying information. With the second, you break contract restrictions, the terms of service saying you can’t use this for this purpose but you can use it for that purpose. And as breaching the CFAA is a felony, that begs the question, for at least us contract professors, is this really a case where a breach of contract is a felony? Judge Kozinski said no, you can’t read the statute like that. He said, “Under the government’s proposed interpretation of the CFAA, posting for sale an item prohibited by Craigslist policies or describing yourself as ‘tall, dark and handsome’ when actually you’re short and homely, will earn you a handsome orange jumpsuit. Not only are the terms of service vague and generally unknown – unless you look real hard at the small print at the bottom of a webpage – but website owners retain the right to change the terms at any time and without notice,” so he holds that “the phrase ‘exceeds authorized access’ in the CFAA does not extend to violations of use restrictions,” it refers instead to “violations on access to information, not restrictions on its use.”

Now, if we could shift into cyberlaw geek mode, there’s something really weird about this distinction, because both kind of restrictions are restrictions effected with what we can say – words, right? One is the words of code, and if you violate that restriction, it’s a felony. Another is the words of contract, and if you violate that restriction, it’s not a felony.

So, for example, if I put a webpage up with these tags, what that will do is in bold at the top of the webpage say, “By using this site you agree not to use the print-screen command.” If I violate that by using the print-screen command, Kozinski says no felony. But if on the other hand I put in my webpage this code, which I’m sure some of the hackers in the room recognize this as code to disable the print-screen command, and I hack around that, Kozinski says that a felony. But literally, these are both just words, words on both sides.

Now you could say the intent to invade is clearer if I’m using hacking technology as opposed to just ignoring something that’s on the site, but standing here in the well of a law school, I’ve got to say it’s a little bit demeaning to recognize that the coder’s words are taken more seriously than the lawyer’s words. [audience laughter] Disagree with the coder and you go to jail. Disagree with the lawyer and you’re just laughed at, because everyone disagrees and ignores the lawyer.

Okay, shift out of cybergeek mode back to this case. It’s because of that case in the Ninth Circuit that the indictment against Aaron was superseded by an indictment that dropped all reference to “exceeding authorized access.” So the only question in the case was whether he had “unauthorized access” to the computer system. So that’s the question, was he guilty of that?

To see that, we have to think a little bit about what he actually did. There was no traditional “hacking” here. Right? Because if you go to JSTOR on a computer here, you’ll see that the URL basically just has a number at the end which is referring to the article. When Aaron saw that, he recognized it was pretty trivial to write a script to download all of the articles; you just needed to write a script that created a URL for every number within the range that JSTOR offered. So it was trivial to just say, “Download an article, download an article, download an article.” It was a script to snarf this as quickly as possible. It’s a little bit too fast for you, but that’s the point. It’s a little bit too fast. It’s as quickly as possible. And when JSTOR noticed this, they blocked his IP. So Aaron took a new IP. And when JSTOR noticed that, they blocked a range of IPs. But that caused some trouble because it blocked all MIT access to JSTOR. [audience laughter] So then JSTOR blocked his MAC address, the address on his computer that particularly tied it to the Acer computer he was using. So Aaron spoofed the MAC address. This was a game played to keep this routine, keepgrabbing.py, a Python script, running. It was a kind of cat and mouse game where Aaron was the cat, JSTOR was the mouse, and maybe this is the modern version of this game [slide of mechanical cat and mouse].

So if you think about it, what happened here, where there were lots of technical tricks to enable the download of lots of articles: He was permitted to have “some” articles, no one doubts that. By contract he was not permitted to take “all” of these articles. And when code was deployed to block him from taking lots, he is alleged to have evaded that code and taken it notwithstanding.

[To be continued.]

K, now I’m sure it wasn’t suicide.

Thanks for the post Lambert. Great talk.

A well done presentation.

Debt of gratitude to whoever transcribed.

The big lie is the biggest threat to American democracy and what’s left of our dwindling stock of civil liberties we still possess. We saw how it worked with the Iraq War, and it has now metastasized into domestic politics. It won’t take much more for antiwar and anti-Wall Street protesters to be categorized as traitors. The last line of defense is the courts, and we don’t know how long that will hold.

Follow-the-money Part 3:

Larry says:

” We academics built this world. It flows from the deployment of copyright that we have chosen. But here copyright is not to benefit authors, it’s to benefit publishers. It’s not to enable authors – there’s not one of the authors on this list who get money from copyright.”

So, who are these unnamed publishers? Which of these publishers benefit as well with the Pacer model? How much do these publishers provide in political donations in the US? Which of these publishers are Dutch, German, English, Canadian?

As always, it all about the money.

Yes indeed Lambert. Thank you.

* * “The U.S. is not America” * *

It takes stones to take on the Feds and big business (academy). They have no strategy but they can lean on you. However …

… if you are making a political point you have to take the political risk which might mean spending some time in prison.

… if you don’t want the risk you have to take another approach such as suing the data-monger or copywrite holder. Schwartz needed a lawyer friend with a Federal practice.

Information challenges conventional wisdom. Conventional wisdom is the core belief system of Washington. If they think it, it must be true.

Thanks Lambert, still reading this piece. I wanted to add something that may be related:

http://www.thenation.com/blog/173167/lobbyists-targeting-liberal-groups-channeled-chinese-hackers-strategy#

Lee Fang

Investigating the intersection of politics, lobbying and public policy.

Lobbyists Targeting Liberal Groups Channeled Chinese Hackers’ Strategy

Lee Fang on March 4, 2013

The revelation, made by The New York Times and a firm called Mandiant last month, that the Chinese military is engaging in a sophisticated campaign of Internet spying and cyber attacks targeting American corporations and government websites provoked widespread alarm. What hasn’t been noted is that the Chinese plot bears much in common with a conspiracy to spy on and sabotage liberal advocacy groups and unions—a plot developed on behalf of none other than the US Chamber of Commerce back in 2011.

Indeed, Mandiant identified the Chinese plot by combing through the database of hacking tools managed by the same individuals associated with the American firm that had been enlisted to help the Chamber execute its spying and hacking plan, before it was exposed by the hacktivist group Anonymous.

Attorneys for the Chamber were caught negotiating for a contract to launch a cyber campaign using practically identical methods to those attributed to the Chinese, which reportedly could be used to cripple vital infrastructure and plunder trade secrets from Fortune 100 companies. The Chamber was seeking to undermine its political opposition, including the Service Employee International Union (SEIU) and MoveOn.org, but apparently had to scotch the plan after it was revealed by Anonymous.

At the RSA Conference in San Francisco, the “nation’s largest gathering of cyber security professionals,” The Nation spoke to a number of experts who said the same invasive strategies employed by the Chinese military could be easily used in political campaigns and other political contexts by anyone willing to take the risk.

snip

Large firms that have been victimized by malicious hacking, including Google and Intel, at least have the resources to detect and counter most forms of computer crimes. But what about a small company, or political advocacy group with little resources?

“Political campaigns, absolutely, they have to be vigilant that they will be attacked,” said Ajay Uggirala, the director of product and technical marketing at the cyber security firm Solera Networks. “It’s going to be a dynamic,” Uggirala explained, “I wouldn’t be surprised if people use the good tools we have for bad purposes on political candidates.”

……….

http://www.bradblog.com/?p=9900

Chinese Cyber Attacks on U.S. Targets Said to Mirror U.S. Chamber of Commerce Cyber Plot Targeting Progressives Such as The BRAD BLOG

By Brad Friedman on 3/5/2013

snip

In Monday’s report at The Nation, Fang details how recent cyber attacks against U.S. interests, which appear to be emanating from the Chinese Military, mirror tactics used by the U.S. Chamber’s thugs in the eventually aborted 2010/2011 attempt to pull off what Fang describes as “one of the most brazen political espionage efforts in recent memory.”

If the New Yorker article by Lisa MacFarquhar doesn’t convince you, look at the coder’s piece on the middle-aged svengalis who led Swartz to his extremities, setting up for the prosecution and the depression and futility that led to his death.

http://3dblogger.typepad.com/wired_state/2013/03/the-middle-aged-svengalis-who-used-aaron-swartz.html

That’s the corporate greed you have to think about — and more than that, the greed for ideological influence.

Digital age is still in its baby form

To be hoped it grows up to be the adult we would hope it to be….

Here’s a link to the abstract of the article “Punitive Damages, Remunerated Research, and the Legal Profession,” mentioned in passing by Lessing in the above transcript. #exxon is listed as a keyword.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1359227

It’s no longer available for download, however there’s a link to a full copy pdf here:

http://www.stanfordlawreview.org/print/article/punitive-damages-remunerated-research-and-legal-profession

We’ll all have to work a little harder now that Aaron isn’t helping all who aspire to be on team impact in the countless little ways that he did.