By The Unknown Transcriber

Lambert here: Lessig, at the end: “That’s what love means. It means working, acting fiercely against the odds. And then my next thought was, you know, even we liberals love our country. [audience laughter] And so this observation of the impossibility of this challenge is irrelevant, because we love. And we love means we act regardless of how impossible this is.” Well worth reading.

This is the full transcript of “Aaron’s Laws” talk given by Lawrence Lessig at Harvard on February 19. A good summary of the talk, by Harvard second-year law student Eric Rice, is here.

Outline of talk:

Section I ran yesterday. Today, we run Section II, followed by the Q&A session.

NOTE: Lessig numbers the parts of his presentation on slides like this: <5> is Part 5. These slides are embedded as thumbnails in the transcript.

Section I:

Intro

Part 1: Aaron

Part 2: Aaron’s works – B©, ©, A©

Part 3: As a citizen

Part 4: The “crime”Section II:

Part 5: Godzilla meets Jefferson and Thoreau

Part 6: Aaron’s laws

Closing: Aaron and usAudience Q&A

1. The arrest, MIT and Secret Service, and Abelson report?

2. What to do about prosecutorial overreach, especially for those who don’t have Aaron’s connections?

3. Easy for lawyers to make things worse, how to make things better?

4. MIT Office of General Counsel running things, not educators? Lawyers huge part of the problem?

5. Aaron’s third law – how to clean up campaign financing?

Lessig begins at about 8:50.

Clicking on the centered images of Lessig’s slides below should take you to that spot in the YouTube.

Now, we don’t know if a jury would have found that to be a sign of guilt. We don’t know whether he would have been found guilty. His attorney, Elliot Peters, reports he was extremely optimistic after the revised indictment was released because he believed he could show Aaron’s access was actually authorized, and he believed that there was a reason why the evidence of his cat and mouse game would not be introduced, and he believed there was no harm done.

But that begs a second kind of cyberlaw geek question. It’s the ambiguous nature of harm in the context of cyberspace. Because think about this question of harm in two separate cases. First, there was no ambiguity about the harm caused by this civil disobedient. [Martin Luther King mug shot] Now, I’m all for it; the harms that he caused by engaging the civil disobedience that he engaged in, I support, I celebrate. But there was real harm there. Disruption, interruption, all sorts of costs in order to deal with the protest which his civil disobedience was supporting. But there is an ambiguity about the harm caused by something like this: [keepgrabbing.py script] You know, if you’re just downloading articles, then you could say it may be causing harm. Depends on the articles, depends on its potential use. But if you’re doing something like downloading credit card data, then it’s certainly causing harm.

So the harm is ambiguous, leading the statute to be ambiguous, meaning the prosecutors have to tie the prosecution to the intent. Here their claim was that Aaron intended to distribute this through file-sharing networks.

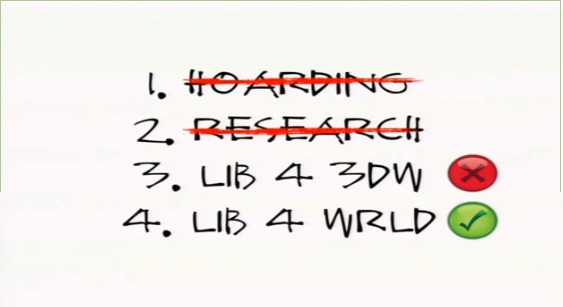

Now, it’s important to notice that of the four possible things he was doing, that’s actually not true about the first two. If he was doing hoarding or research, there was nothing about distribution involved. It’s not even clear about liberating with respect to the Third World – the Third World notoriously doesn’t have great Internet access. The alternative modes of distributing might be actually physical devices that are located in universities around the Third World. It would have been true about liberating JSTOR for the world. But even here, the harm that would have been caused from both of those is ambiguous.

The US Attorney uttered at the time when they celebrated the prosecution of Aaron – they don’t celebrate it much anymore – but in the press release said, “Stealing is stealing whether you use a computer command or a crowbar,” leading me to suggest it sounded like she didn’t know much about computers or crowbars. Because with respect to harm, that claim is just not true. With respect to harm, think about both of these. For Third World liberation, the Third World had no access to JSTOR. The access Aaron would have granted would have been no harm to JSTOR. And even with respect to the First World, there is not a single institution that pays JSTOR that would then say, “There’s no need for us to pay for JSTOR access because our professors can get it illegally on the BitTorrent servers.” [audience laughter] So there was zero market harm here. Which is why JSTOR wisely and quickly said, “We don’t have a dog in this fight and we don’t want you to pursue it.” So when you think about this point of committing crimes with a computer or a crowbar, the point to recognize is that computers are sometimes harmful, crowbars are always harmful, which evokes perhaps the most quoted letter in the history of the United States from a United States president quoted in this law school, letter of Jefferson to McPherson, explaining why in fact this was true. As Jefferson wrote:

If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess so long as he keeps it to himself, but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it. Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me receives instruction himself without lessening mine, as he who lights his taper at mine receives light without darkening me. That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe for the moral and mutual instruction of man and improvement of his condition seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature when she made them like fire expansible over all space without lessening their density at any point, and like the air in which we breathe and move and have our physical being incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation.

Until the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

These harms can, but they need not, produce harms. And so what this shows is that we need prosecutors who can tell the difference, who can tell the difference between Aaron and evil. Judge Kozinski reported that in response to his questions at the oral argument at Nosal, the government assures us, the government assures us, that it won’t prosecute minor violations. But the most striking thing of this prosecution is that the more they knew about Aaron, the more vicious they became. Their assurances notwithstanding, they became more intent to fight to make this an example. Instead of just simply saying, “I’m right,” they adopted the ethic of “I’m right and therefore I’m right to nuke you.” They bullied, as I’ve said. They played an example justice game, the “teach him a lesson,” here, a lesson that was lost on him and therefore lost for us.

Now, you don’t need to believe that Aaron was right to see why what the government did here was wrong. Even if it was right that he committed a crime, still it was wrong for them to behave so disproportionately in response to that crime. In an age where the architects of financial disaster dine regularly at the White House [Lloyd Blankfein smiling at Obama], or when as Elizabeth Warren last week got us to recognize, regulators can’t even find a reason to take a bank to court, what interest, what reason, why did the government need to insist that this boy be labeled a felon?

Henry David Thoreau, on civil disobedience, wrote this:

Unjust laws exist; shall we continue to obey them or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once? Men generally, under such a government as this, think that they ought to wait until they have persuaded the majority to alter them. They think that, if they should resist, the remedy would be worse than the evil. But it is the fault of the government itself that the remedy is worse than the evil. It makes it worse. Why does it not cherish its wise minority? Why does it cry and resist before it is hurt? Why does it not encourage its citizens to be on the alert to point out its faults, and do better than it would have them?

Five weeks and four days after the hopelessness of this fight overcame him, I still want to know why.

But the question here is what should be done? Immediately after his death, Zoe Lofgren – you remember her from Aaron’s first thought about maybe there is one Congresswoman who might possibly see the idiocy in COICA – Zoe Lofgren wrote to say she intended to introduce something she wanted to call Aaron’s Law. But not in Congress. She introduced it first at Reddit. And she asked the people in Reddit to comment on the bill, and there were thousands of these comments, and then she took those comments and redrafted it in light of those comments and now has submitted it. EFF identifies three crucial things any new bill should do. It cannot criminalize violation of private agreements, it must allow people who have access to the information to do it in an innovative way, and the penalties need to be proportionate to the computer crime. They believe this draft bill would work to achieve the first two of these elements.

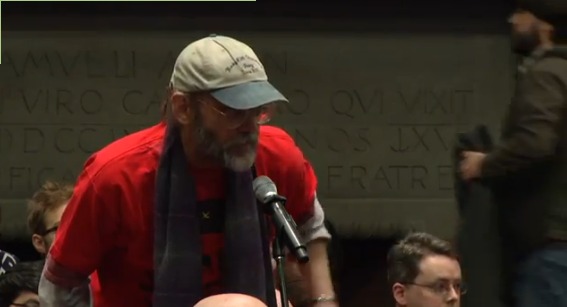

And I believe this is an incredibly important and significant and valuable piece of legislation, and it’s enormously fun to see a bill where Zoe Lofgren and Daryl Issa stand on the same stage supporting the reform. Indeed, at the memorial service at the Capitol, this is Daryl Issa [at mike]. Daryl Issa giving a speech about how he celebrated Aaron’s desire to, quote, “stick it to the man,” end quote. [audience laughter] And this was an amazing event. It was filled with members of Congress. Now, as most members of Congress – it was filled with members of Congress who came for 10 minutes or 15 minutes, most of the time sat there with their Blackberry, all of them wanting to speak except for one, this woman, Elizabeth Warren, who came, who sat through the whole of the event, asked not to speak, didn’t once look at her Blackberry, but tried to understand the tragedy which we were talking about.

This bill would be great. Aaron’s Law is great. But. There should be no illusion. Aaron’s Law is fundamentally incomplete. Aaron was a hacker, but not just a hacker. He was an Internet activist, but not just an Internet activist. He was a political activist, but not just a political activist. He was a citizen who felt a moral obligation to do what he believed was right.

And if he was guilty here, it was because he acted on that view of what was right. And we need to act to respect that act of citizenship.

To think beyond what Aaron did. To think beyond what was done to him. To think about the ideals he gave everything in his life to and to make those ideals the law.

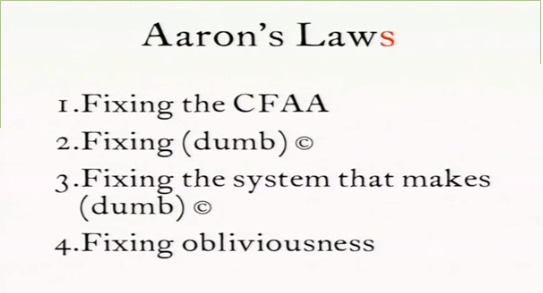

So obviously, first, we need to fix the CFAA. But the list of Aaron’s Laws is more than this one.

Number two: We have to fix dumb copyright. For we are here in part because of dumb copyright laws. For example, what got me into the copyright activist phase was a statute in honor of this great American, the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act. A statute which extended the term of existing copyrights by 20 years. The question Congress was to ask when they passed this statute was, “Did it advance the public good?” So obvious was it that you couldn’t advance the public good by extending the term of an existing copyright, that when we got a bunch of economists to join a brief attacking the bill in the United States Supreme Court, this liberal left-wing – oh, I’m sorry, this is Milton Friedman – right-wing Nobel-Prize-winning economist said he would join the brief only if the word “no brainer” was somewhere in the brief, so obvious was it that you couldn’t advance the public good by extending the term of existing copyright. But apparently there were no brains in this place

when Congress unanimously extended the term of existing copyrights. What there was was more than six million dollars in contributions from Disney and related corporations eager to see their copyright extended, the public good be damned.

Or think about this example. This is a bill called the Research Works Act. The background of this bill is the policy of the National Institute of Health that says that all government-funded research after 12 months has to be available for free download. There are companies that don’t like this. [Elsevier logo] They don’t like this because despite the Consumer Price Index rising like this [moderate upslope] over the past chunk of time, their serial price has risen like this [much steeper]. They realize they’re making an enormous amount of money by selling access to these articles, including articles that have been funded by the taxpayer. So what this bill does, the Research Works Act does, is ban the government from promoting open access for government-funded research. Why? Well, according to the press release when the bill was released, it would save American jobs. Raising the puzzling question, How, when you increase taxes, do you get more jobs? Because effectively we have to pay for the research twice, one when it’s produced and one when we finally get access to it.

Second, it was said “to advance the public interest in the important peer-review publishing system,” forgetting of course that peer review is free. Nobody gets paid for peer review, and there are important journals like the Public Library of Science that have open access as a way of making work available without the need to control exclusive rights. So what explains this bill? I have no idea, but here’s what MapLight points out. The people who support the bill got six times as much funding from interests that were affected by the bill than people who opposed it, and the person introducing it literally got 40% of the contributions from Elsevier and related corporations that they gave to anybody in the United States Congress.

So. This is a need here, a need for a copyright law that thinks about copyrights and purpose. And in part that purpose is to support a public domain. And so when we think about the second of Aaron’s Laws, we need to fix this dumb copyright law so it serves that underlying important purpose.

But even more important, number three, to fix the system that makes dumb copyright laws and other laws, environmental laws, healthcare laws possible. Because these dumb laws are law in part because of this thing Aaron identified as corruption. And not just Aaron. As he left the United States Senate, John Kerry gave a speech on the floor where he called it corruption too. He said, “I mean…the corruption of a system itself that all of us are forced to participate in against our will: The alliance of money and the interests that it represents, …the agenda that it changes or sets by virtue of its power is steadily silencing the voice of the vast majority of Americans … who can’t compete at all.” This law is to recognize this cause, the cause of this corruption, and the cause is the way we fund our elections. This is the roots, and to take again Thoreau’s words, “If there are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one striking at the root,” this is the root that the rootstriker, Aaron, would insist that we change. And we change to end this corruption. That’s number three. Three laws Congress can enact.

But the fourth is the most important, and it’s a law that we need to enact. It’s a law to fix the obliviousness that we live our daily life with.

Aaron was a supertaster. A supertaster with food. Really hard to have him with dinner because he couldn’t eat anything because everything was overwhelming in its taste. He could only eat the blandest of food. But he was also a supertaster about injustice. He just didn’t get the obliviousness that he saw around him to injustice, individual, institutional. And there was obliviousness here with respect to this case, in institutions and individuals within the institutions, individuals who did nothing to bring a system around to recognize the insanity of what was being done. Now not just obliviousness. There are plenty who did plenty. John Palfrey, Jon Zittrain, Hal Abelson, Joey Ito, did an extraordinary amount, plenty to try to get the system to recognize it, but none of us did enough against that obliviousness. And against that obliviousness, Aaron faced it with a certain earnestness, a certain brilliance, a certain utter simplicity, asking the question, why? “Could it really be true that this is what was going to happen to me because of a few scripts and breaking a few rules?” And he asked us as citizens to explain why, how could we justify this?

His final law: We must find, we all must find a way to inspire in all of us a recognition of the supertaster everywhere. A recognition of when these institutions find their way into this corner, that we have the obligation as citizens to pull them back. To say, “Enough.”

I think it was 21 years into my life before I did anything that Aaron Swartz would have been proud of. But when I was 21, I did something I’m sure he would have been proud of. A young Republican that I was – he wouldn’t have been proud of that part, but okay – I decided to travel to the former Soviet republics – I mean to the Soviet republics, this was 1982 – and to Eastern Europe, to explore communism, to understand it. And I kept a diary. There were no blogs back then, but I kept a diary. And I recorded the facts that struck me as the fundamental difference between these societies.

So, for example, there was the difference of lotteries. We had no lotteries in the United States then. They had lotteries throughout Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union then. People were obsessed with lotteries. That’s the way they were going to make it – lotteries! And I wrote self-righteously in my book, “In America we make it by working hard, not by lotteries.”

The second point I remember remarking was, I almost got arrested because as I crossed the border they told me to take off my shoes. I said, “This is barbaric! I’m not taking off my shoes! That’s ridiculous!” And somebody told me, “You can’t disagree with the people at the border. You’re going to get arrested. You have to take – ” So I took off my shoes.

But the next two are directly relevant. I want you to think about them as you think about this case. The third was a professor in the Soviet Union who said to me, “You know, the Soviet Union is not so bad. It’s not so bad. As long as you stay on the straight and narrow, everything is fine. You take one step off the cliff, you fall into oblivion, but stay on the straight and narrow, everything is fine.” And the second image, an overwhelming image, was on a bus traveling to Romania, long lines, it was going to take an hour to get across the border. And way up in front I could see a truck carrying geese. The truck hit a bump. The back opened up and the geese all fell out. And I pointed out, “There’s geese, look, all over the road.” But the line, which had been moving methodically, was not about to stop for these geese. And so the line of trucks and buses just rolled over these geese. No one stopped. No one hesitated. And I in my kind of frantic Americanesque way, “Look! Look! Look!” People looked at me, “What’s the matter with you? It’s just geese.” Look at the cliff, and the geese.

Now obviously the United States is not the USSR. But is the United States America?

It’s not surprising that it was a Romanian immigrant who noticed that there was something bizarre about trusting the government to tell the difference between minor and major prosecutions. As he said, “We shouldn’t have to live at the mercy of our local prosecutor.” Is the United States America anymore?

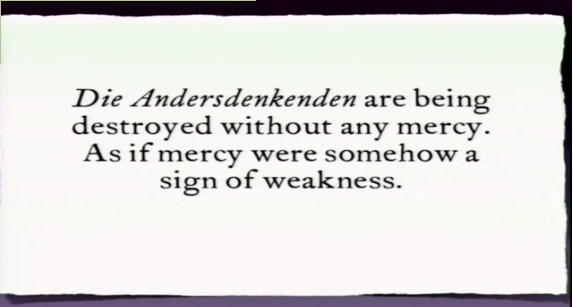

After Aaron died, a friend of his and mine who had known him for as long as I knew him, wrote me, a German filmmaker, a German filmmaker wrote me an e-mail, and he said, “Aaron was a victim of a strangely fascistic spirit that has developed in America over the past decade or so. Die Andersdenkenden are being destroyed without mercy. As if mercy was somehow a sign of weakness.” Die Andersdenkenden, which translates roughly as “those who think differently.” Now it would have been the last thing in the world that Aaron Swartz would have wanted to be linked to a commercial by Apple. [audience laughter] Not because he hated Apple products – he was a total Apple nerd – but because that company seems increasingly to stand for none of the values that Aaron celebrated or fought for. But Aaron would recognize the sweet and sad irony of us living in a time where the only place we can celebrate those who think different is in a television ad from a company whose image of the Internet is me.com.

Why just there? Why do we even allow it there? If this is America, if this is America, we need to protect that right, that right to think differently of all of us. We need to protect it here, and we need to fight for it, by holding accountable those who would crush the soul of a boy like this and defend it as “appropriate.”

Forget think different. Think Aaron. Think of what we did to him, and think of the laws that we must enact to make it right. Thank you very much.

[standing ovation]

Q&A

Lawrence Lessig: Thank you. So I’m happy to take a couple of questions. And I see my contract students here, so I can just cold call on them. Schuman! You! (laughs)

(turns to other side of room) Yes, sir.

Audience member #1: So, thanks, Larry, for your work with Aaron and for honoring his legacy in the way that you are. I have two things that I’m interested in. One is, you said that Aaron was arrested in Building 16. There is an account of his having been pursued down Mass Ave by an MIT campus police officer and a Secret Service agent, and I would be interested to hear you talk about how the Secret Service came to be involved in this and why. And the second thing is, Hal Abelson, who you mentioned in your lecture, has been asked to do an internal investigation by the president of MIT, and I’d be interested to hear your comments on whatever you may have to say about MIT’s role in this and culpability. I know it would be preliminary, but. Thank you.

Lawrence Lessig: Yeah, so, yeah, I think I misspoke about the framing of 16. 16 is where it happened. He actually did some other work in a student dorm I think after that, but it was the activity at 16 that was the core of the indictment. He was arrested on Mass Ave, as I understand. So you’re right about that. About the – uh. About Hal Abelson and MIT. Look, I think MIT is going to face some very difficult questions as it comes to recognize what happened here. I think they behaved extraordinarily badly. I mean, when we were talking about this case originally, trying to figure out how to defuse the bomb, the hard question for us was JSTOR. How would we get JSTOR to understand this case? And, I don’t know if I’m allowed to say this, so don’t tell anybody, but, you know, Palfrey was central in calling the head of JSTOR and saying, “Look at what happened. Look what this is about.” And JSTOR quickly backed away. And when that happened I was certain the case was going to go away. Because this is MIT, for God’s sake! It is where hacking is celebrated. It is where Richard Stallman lives! How could MIT be a place that continued to press in this? But they didn’t. They refused. Now. Saying that, I do want to say that the most astonishing thing to me after this happened was how quickly MIT came around to say, “Look, we’re going to look at this very seriously, and there is no better person at MIT to look at it than Hal Abelson.” I have known him for longer than Aaron and I trust him that he will give the right answer and MIT I think will do the right thing. And it was in contrast between what MIT did and what the government did that made me so angry and frustrated about this case, because it’s not as if the government even said for a moment, “We’re going to look at it. We’re going to think about it. We’re going to think about it.” They said immediately it was appropriate. “It was appropriate. Shut up, it was appropriate.” You know, now, the reaction of the world suggests the government lives on Mars and they don’t recognize this, and this is the question, like, you know, how do we bring them back down? And, you know, Judge Gertner very quickly sort of gave us a sense of her own recognition of the reason for this gap inside of a prosecutor’s office. I think we need more conversation like that. Because prosecutors have no liability for what they do. None. We give them complete immunity. And if we give them complete immunity, we need ways, culturally, for us to pull them back and to be able to say, “Can you really justify what you’re doing? Something more than just a way to make progress inside your career.”

Audience member #1: And how did the Secret Service come to be involved?

Lawrence Lessig: Oh, that’s another good – you know, I actually think that if there’s a major computer, you know, issue, it’s completely appropriate in the first moment to be as careful as you can to figure out what’s going on. Look, there are a lot of really bad people abusing computer networks for all sorts of terrible reasons. So I think it’s fine the Secret Service – I don’t know exactly all the things they do, you know, the president was safe, maybe they figured they could look at this problem, but, you know, whoever, I don’t care if in the first round you are as careful as you can to make sure there isn’t really a serious imminent threat of some real damage being done. But that again is the thing that drove me nuts about this case. The more they knew, the more hardened they became. As opposed to, “Oh, okay. We realize this is not a bin Laden escapade, this is not some guy trying to bring down the government or steal Citibank’s credit card information or reveal all the secrets of nuclear testing that might be held at MIT,” none of that. Instead of saying that and then therefore saying, “Okay, now let’s find a way to slap him on the wrist and move on,” they said, “No, we’re going to make this a serious case.” And they go from four charged indictments to 13, and they continue to insist he will have jail time and be named a felon.

Audience member #2: Thank you for this wonderful and inspiring speech. My question touches quite a bit upon what you were just speaking about, which has to do with prosecutorial discretion. You mention in your speech that a friend of yours had said that this has become a greater problem perhaps over the past 10 years, but I actually found myself reading a journal article that was released in 2001 that bemoans the fact that prosecutorial discretion and the problem of expansive laws and in fact ever-expanding laws are something that has eclipsed the legal journalism as it applies to criminal law. It’s indeed a very longstanding issue. So, what are we to do about the deeper issues here, particularly those people who unlike Aaron don’t have some of the best legal faculty to speak out on their behalf?

Lawrence Lessig: Right. So there are two separate issues going on here. One is the general issue of prosecutorial discretion. And again I make another plug for Charles Ogletree’s event on March – 6th? Because Tree is as expert in the general question of prosecutorial misconduct or overreach as anyone. So that will be a fantastic context in which to think of this problem generally. But the particular problem that I think we can distinguish from that is the way in which computer laws are being framed. Right? So, it’s the fact that to make yourself a civil disobedient here is to throw yourself off the cliff, as opposed to expose yourself to 30 days in jail because you sat down at a lunch counter. And it’s the extremism here that I think originally might have been justified in the context of “We don’t know about computers, let’s just say everything is illegal and then we’ll trust the prosecutor.” But now that we know we can’t trust the prosecutor, we’ve got to think carefully about how to carve back the extremism. So, Aaron’s Law, the draft that Zoe Lofgren has pushed, would do a significant amount of that. It’s now got some strong opposition from some tech companies who want to be able to turn their terms of service contract into a felony if it’s breached, but I think we’ll be able to resist that. And so that would be important progress. Yochai has suggested a way of approaching this that tries to identify a kind of activity that would clearly be marked as a misdemeanor as opposed to a felony, which would completely change the character of this. I think there are a lot of things we have to think about about how to make computer law more realistic as well as think about how do we make prosecutors more responsive to this underlying principle, a principle as important to us as to any other democracy, of proportionality.

Audience member #3: Professor, for those of us who are lost in it’s clear the ways in which we act in the role of being lawyers is to make this problem worse, whether as prosecutors, whether in some cases as lawmakers, and there are very few ways where it seems apparent how we can make it better. Do you see any avenues for action – you know, for law students, for future lawyers, to really work to correct this, you know, beyond that, you know, general capacity we all have as active citizens?

Lawrence Lessig: So, I’m a law professor because I think the law has enormous potential to do good, and that lawyers, especially American lawyers, trained in the way we are, have an enormous potential to do good. But it takes a certain courage, which simultaneously our legal culture tries to drive out of us. The courage to put your head up and say, “No way. This is wrong. This is just wrong.” Now, I do think there’s a way in which law students and lawyers can develop the strength in order to do exactly that. One is to tell stories about people who do it, who are willing to do it. Another is to encourage and to protect people who do it. But I think that this is a general problem. It’s a general problem of morality. At the Safra Center for Ethics, this is a feature or a bug of the thing we call institutional corruption, people who become complicit in a system that is not driving to the objective of the system but is driving to something else, usually private financial gain. So there will be a million opportunities for you between now and the time you retire to do the right thing or to do the easy thing. And if you do the right thing too much, you might retire too early – I get that, I understand that. I mean, you’ve got to pick your fights. But you need to pick fights. You need to decide, who am I going to be? You know, I – for the rest of my life, for the rest of my life, it will be that quizzical smirk of this kid looking at me and saying, “Yeah, as an academic, but as a citizen?” that will force me in everything I do to think. We’re paid enough to afford to be able to do what’s right. We have to do that. That’s the only – and we especially, this is the only profession that has this at its core of an ideal. So yes, you can and you should and I hope you will.

Audience member #4: I’m going to ask a related question to the question which you were just asked. I notice that nine years ago MIT for the first time got a general counsel and set up an Office of General Counsel, and in the last case in which I represented an MIT student it was obvious that it was the lawyers who were running the prosecution of the student rather than any faculty members. My question to you is whether my sense that the universities have been taken over by the lawyers, the general counsel, and no longer run by the educators, might have something to do with MIT’s attitude. I can’t wait to see the Abelson report, but I have a sneaking suspicion that will be part of the answer. And so lawyers, I agree with what you just said, lawyers can be part of the answer and the solution, but I also think they’re a huge part of the problem.

Lawrence Lessig: Some. Maybe. I think the Abelson report is [going to give us] a more complicated set of responsibility. It is true, the faculty has stepped back from taking responsibility at MIT for decisions like prosecution decisions, but it’s not so much that lawyers have taken over as that the security division has taken over, the police themselves, the MIT police. So, there’s going to be a question of responsibility, and I’m the first to jump on lawyers, but I’m also the first to say that this is the pool we have of people who can articulate reasons why what we need to do is better than what we’ve done.

Let’s take one last question.

Audience member #5: I wanted to go the third law that you proposed, because I think it is really frustrating to do social justice work and to see things overturned and to see the massive pile of money that looms on the other side, and even, you know, in Massachusetts we had the clean elections law and then that was overturned, and attempts to change the redistricting also never happened, and it’s because the people that we already have in there are benefiting from the current system, even if they pay lip service to how much they might despise it. And so I was wondering if you could expand a little bit on how you think we might get around the chicken-and-egg problem with campaign finance.

Lawrence Lessig: Yeah, so, the complete rationalist in me says, you know, the odds of us winning? Almost exactly zero. Almost exactly zero. Because the enormous benefit to the insiders of this system can only be overcome if you have political power equally as strong. And the problem is all the political power is inside that system, right? So what’s our resource? And so when I think of this in a completely rational way, you know, I wouldn’t suggest anybody spend any of your time working on this issue. [audience murmur]

Audience member #5: Too late.

Lawrence Lessig: So why do I spend all of my time working on this issue? [audience laughter] So this is a story I’ve told a bunch of times. Let me just tell it one last time, and then… So, I write about this in my book. I was speaking at Dartmouth. A woman said to me, “Professor, you’ve convinced me. You’ve convinced me. This is completely hopeless. There’s nothing we can do.” And as I wrote in my book, when she said that, I had an image in my head of my kid, who then was about 6. And I thought, what if a doctor came to me and said, “Your son has terminal brain cancer and there’s nothing you can do.” Would I do nothing? You know, obviously no. You’d do everything. You’d do everything. You know, and that is what love means. Right? That’s what love means. It means working, acting fiercely against the odds. And then my next thought was, you know, even we liberals love our country. [audience laughter] And so this observation of the impossibility of this challenge is irrelevant, because we love. And we love means we act regardless of how impossible this is. But because of this – and that is, I think, the – that is the emotion that we need to find here. And for me, it really is deeply tied up with love, not just a country of us, kids, you look at these kids, three of them, in my life, handing over a world that is miles below the world that I inherited from my parents. And no hope for fixing this until we fix this problem. So, yeah, it’s hopeless. It’s just the only fight we have. Only fight we have.

Thanks very much.

Larry Lessig hasn’t taken the logical step yet.

He’s working within the system because he sees it as the only thing he can do.

Watch out when he, and other paragons of the legal system, make the decision that there is something else they can do.

Lawyers were leaders of the French Revolution.

Lessig is as eloquent as I have ever heard or read him. A very good piece on Aaron, copyrights, law and what passes for justice in the United States.

Is it still America?

To Larry:

Thanks for the research re Elsevier excerpted below.

That would by Reed Elsevier which also owns Lexis. Lexis downloads in bulk everything new on Pacer and then resells on Lexis. Because of its large size and ability to spread costs over many users, it is economical for them to download huge amounts and resell. For decent searching, Lexis and Westlaw have the effective monopoly on searching Pacer.

It it not an odd coincidnece that Swartz was first investigate for threatening this Pacer monopoly and then was investigated and charged for the JSTOR download.

“… The people who support the bill got six times as much funding from interests that were affected by the bill than people who opposed it, and the person introducing it literally got 40% of the contributions from Elsevier and related corporations that they gave to anybody in the United States Congress.”

PS

Lessig has been working on these issues since 1981 at least.

With respect to Aaron Swartz. Having read and listened to the full text here, and read the Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman/ Quinn-Norton link posted yesterday :

http://news.firedoglake.com/2013/03/04/aaron-swartzs-partner-accuses-prosecutors-of-misconduct-as-quinn-norton-details-grand-jury-testimony/

I’m at loss to understand what crime the young man committed which was so horrendous, and I’m appauled at the unnecessarily harsh treament used by the prosecution, while there are zero attempts to prosecute those responsible for the financial crisis, mortgage fraud, money laundering etc., of which we are well aware

In light of that, I am posting these two links which i came across while looking for further information on the whole subject..

https://petitions.whitehouse.gov/petition/remove-united-states-district-attorney-carmen-ortiz-office-overreach-case-aaron-swartz/RQNrG1Ck

https://petitions.whitehouse.gov/petition/fire-assistant-us-attorney-steve-heymann/RJKSY2nb