Yves here. I wonder if the pattern described in this article, which is basically a brain drain of inventors to the US, is playing a meaningful role in the degradation of public education in the US. Why do the elites need to care about home-grown “talent” if they exploit the investments in schooling made by other countries?

By Carsten Fink, Chief Economist, Ernest Miguelez, Researcher in the Economics and Statistics Division, and Julio Raffo, Researcher in the Economics and Statistics Division, World Intellectual Property Organisation. Cross posted from VoxEU

Migration is a hot-button issue across the globe. This column summarises new evidence on the patterns of skilled-worker migration, focusing on the specific case of inventors. A novel data source that traces worldwide migration flows for inventors suggests that, excluding a few nuances, the economic incentives for general migration also seem to influence inventors’ migration decisions.

Many countries are currently debating and reforming their immigration policies. One prominent question in these discussions is how to attract skilled workers that can ease domestic skills shortages and foster innovation and entrepreneurship.

Examples abound of how the foreign-born contribute to scientific progress, technological advances, and business success. We estimate that around 30% of Nobel Laureates resided outside their home country at the time of their award.1 Take the case of Professor Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, who received the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome. Professor Ramakrishnan was born in India and studied at Ohio University. When he received his Nobel Prize, he worked at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology of Cambridge in the UK. Like many of his fellow Nobel Laureates, Professor Ramakrishnan has been a prolific inventor, applying for numerous patents.

Going beyond anecdotal evidence, how important is the contribution of skilled immigrants in different countries? What determines their decisions to migrate and how do these decisions affect host and home countries? In this column, we use a novel data source that traces worldwide migration flows for one specific class of skilled workers – namely, inventors. We review the main patterns emerging from the data and discuss preliminary evidence on what leads inventors to migrate.

What can patent data tell us about skilled migration?

Economists have made important progress in better understanding the causes and consequences of skilled-worker migration (Docquier and Rapoport 2012). New cross-country census-based databases have been an important impetus behind new insights (Carrington and Detragiache 1998, Docquier and Marfouk 2006, Özden et al. 2011).

Yet, despite these improvements, important data limitations remain. Census-based datasets observe migration stocks only every ten years. Countries differ in how they define skilled workers, especially when the sample includes non-OECD countries. In addition, existing skills categories are often broad; the qualification of tertiary-educated workers, in particular, may range from non-university technical degrees to doctoral degrees.

To overcome these limitations, we rely on an entirely different information source – patent filings. Patent data are available for many countries and without any break in time. In addition, they capture inventors – a class of workers at the upper tail of the skills distribution and arguably a more homogenous class than tertiary-educated workers as a whole. More generally, inventors have special economic importance, as they create knowledge that is at the root of technological and industrial transformation.

Patent documents list the companies or individuals applying for the patent; equally important, they list the inventors who have contributed to the invention for which the applicant seeks protection. Unfortunately, patent documents typically record only the names and addresses of inventors, but do not provide any further information on an inventor’s biography. Agrawal et al. (2011) and Kerr (2008) have identified immigrant inventors relying on the cultural origin of inventor names. This approach has yielded important insights; however, it can only be applied in certain jurisdictions and it may be misleading when the migration history of certain ethnicities spans more than one generation.

Fortunately, it turns out that there is one patent-data source that offers direct information on inventors’ migratory background. Patents filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty contain information on both the residence and the nationality of inventors – largely as a result of the Patent Cooperation Treaty’s eligibility criteria. Employing Patent Cooperation Treaty data offer additional advantages for mapping inventor migration flows worldwide. The treaty has wide coverage and applies a single set of procedural rules to patent applicants from around the world. Moreover, applications under the Patent Cooperation Treaty are likely to capture the inventions that are commercially most valuable, given that applicants are willing to bear the costs of pursuing a patent in several jurisdictions. In total, we observe close to five million records containing information on the residence and nationality of inventors (Miguelez and Fink 2013). Professor Ramakrishnan appears in several of these records.

So Who is Winning the Race for Inventors?

Existing datasets point to an overall migration rate of 1.9% in 2005, and 4.8% for tertiary-educated workers. Our data suggest that inventors are far more mobile, with 10% of inventors worldwide showing a migratory background in 2005.

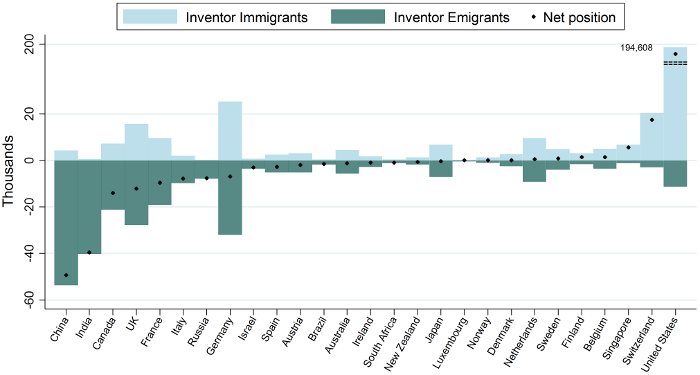

The US is by far the most popular destination for migrant inventors (Figure 1), hosting 57% of the world’s inventors that reside outside their home country. Moreover, there are 15 times as many immigrant inventors in the US as there are US inventors residing abroad. Switzerland, Germany, and the UK also attract considerable numbers of inventors. Interestingly, though, Germany and the UK see more inventors emigrating than immigrating. Canada and France similarly show a negative net inventor immigration position.

Figure 1. Immigrant and emigrant inventors (in thousands), and net migration position, 2001-2010

Immigrant inventors account for 18% of all inventors residing in the US. Several small European countries see even higher immigration rates –notably, Belgium (19%), Ireland (20%), Luxembourg (35%), and Switzerland (38%). Among the larger European countries, the UK (12%) shows a relatively high share of immigrant inventors. By comparison, foreign nationals only account for 3% to 6% of all inventors in Germany, France, Italy and Spain. Japan is the only high-income economy with an inventor immigration rate of less than 2%.

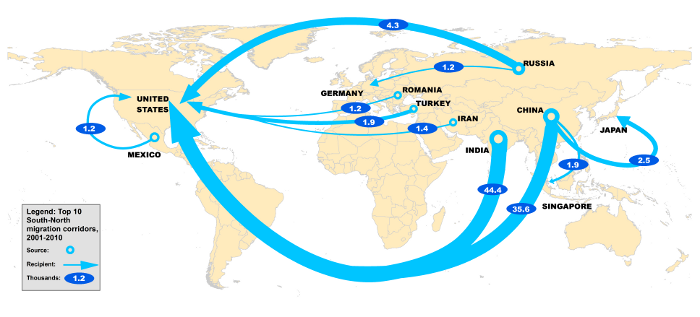

Inventor migration is a concentrated phenomenon. The 30 most important bilateral migration corridors account for less than 0.08% of all corridors in our dataset; yet, they account for close to 60% of overall inventor migration. Among the 30 top corridors, the US is the most frequently listed destination. Most origin countries are other high-income countries, although the top two corridors – China-US and India-US – have middle-income country origins.

Looking specifically at south-north migration, the lead position of the US is even more pronounced: close to 75% of migrant inventors from low- and middle-income countries reside in the US. China and India clearly stand out as the two largest middle-income origins, followed by Russia, Turkey, Iran, Romania, and Mexico (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

What Leads Inventors to Migrate?

In follow-up research (Fink et al. 2013), we study what determines the location decisions of inventors. We find that many of the variables that explain overall migration also explain inventor migration. In particular, economic incentives positively affect inventors’ decisions to migrate and the costs of relocating to another country exert a negative influence on these decisions.

However, interesting differences with the general population of migrants emerge. Most migration cost variables exert a smaller effect for inventors than the general population. We interpret this as evidence of highly skilled migrants being better informed about job opportunities, being more adaptive and being better able to surmount legal obstacles to migration. One notable exception is sharing a common language with the destination country, which we find to matter more for inventors. This could suggest that communication plays a more important role for highly skilled occupations.

Another interesting finding is that income in the destination country matters considerably more for south-north inventor migration than overall inventor migration; the estimated income elasticity is almost double in size. This suggests that the determinants of inventor migration differ according to the origin of inventors. In particular, differences in skills rewards appear to be the main explanation for south-north migration. In line with this hypothesis, we find south-north migration to be almost exclusively unidirectional. By contrast, differences in skills rewards appear to be less important for north-north inventor migration, where inventor migration is often bidirectional (trade scholars will notice an intriguing parallel to patterns of inter-industry versus intra-industry trade).

The resulting question is why we see, for example, German inventors emigrating to the US and US inventors emigrating to Germany. One explanation may be that inventors specialise in certain skills and different locations specialise in research activities demanding those skills. There may well be other explanations. More research is needed to refine and deepen our understanding of what explains bidirectional inventor migration patterns.

Conclusions

This column summarised new evidence on the patterns and determinants of skilled-worker migration, focusing on the specific case of inventors. We believe that patent data can shed new light on the causes and consequences of skilled-worker mobility. In addition to the research outlined here, our data can offer insights into the influence of skill-selective immigration policies. More generally, they can be used to study how immigrants contribute to innovation performance in the host country, what role they play in the international diffusion of ideas, and how diasporas and return migrants benefit the economies of sending countries.

Scholars have emphasised the latter dimension to argue that skilled migration is not a one-way street. To return to our original example, Professor Ramakrishnan has rebuilt his ties with his homeland and regularly visits Bangalore, where he interacts with colleagues – especially young scientists.

See original post for references

One problem – some, perhaps a significant proportion of US patents are total garbage – perpetual motion machines, doing X with a computer, doing X over the internet (when X is a well known activity) etc.

I think one should always be wary of the Creator Class meme. The impression this article gives is that these people are all John Galt and whomever attracts them will have the wherewithal to drag their lazy citizens into the future.

Currently our system gives most people as little as possible. The best way to develop “creators” would be to distribute education, income, and leisure time as widely as possible. Most people might fritter it away, but it would maximize the chance that some would invent things that change the world.

“Why do the elites need to care about home-grown “talent” if they exploit the investments in schooling made by other countries? ”

Exploit is the key word here, not reward. Inventors are exploited in the US, not fairly rewarded. Just take a look at the Patent System and you can easily see why this is so. You file your invention with the Patent Office and then it is open season on you by anyone who wants to violate your patent. It is your obligation and your cost to defend your patent.

So, brainchild, your new widget is the wonder of the world. BUT GM is in agreement and decides to steal your patent. Good luck, Mr. Shallow Pockets, defending your patent.

“You could easily argue that if Microsoft and Apple were started today they would absolutely be harmed by today’s patent system, but not in the way that Choate or Fingleton suggest. Rather, they would be sued by trolls over and over and over again, meaning they’d be wasting money fighting lawsuits, and possibly wouldn’t be able to survive that. What they needed to survive was an era in which patent enforcement was not common and especially one where patents were considered inapplicable to software. ”

http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20130401/01463022521/author-claims-that-if-apple-microsoft-started-today-theyd-fail-without-stronger-patent-protection.shtml

I looked into a patent years ago and I read that the Japanese when attacking a problem look through all the patents filed in the World and then use that information as the basis to attack the problem. And, if one patent turns out to be the best, well they just violate it. So, a patent puts your invention in the public record for all crooks, thieves and liars to steal. And we know, from the Financial Crime Wave, there are many of these people out there.

So, there are many inventors who know all the above and don’t give up the goods. They just do other things like going the Trade Secret route. Or, more likely, they do not invent.

There is a well known case about this concerning Robert Kearns who invented the intermittent wiper which was ripped off by the Big Three:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Kearns

There is a movie about Kearns, Flash of Genius, not a pretty picture about the inventing payoff. This is maybe available at your very inventive file sharing service, Pirate Bay. We know for sure they didn’t go the Patent Route.

So, maybe we should have a system which rewards and encourages all inventors, domestic or foreign.

I am in that situation right now. Was negotiating with a large company when my patent application published. They stopped talking and stole it. Now I’m waiting for issue, but it’s rather painful.

Good point that everyone can relate to. In the pharmaceutical industry it is notorious for companies to invent some new useful molecule and then have competitors knock-off an atom here or there and re-patent it as their own.

The point about big companies using their wealth to defeat small inventors who go to law is also well-established.

In fact big companies used to enforce their own intellectual property up until 1980s but it was difficult and expensive so they leaned on governments to pick-up the tab for enforcement – what a silly move that was. The only people happy with it are those ideological politicians with agendas – they use it to beat-up countries who are insufficiently rigorous in fulfilling their new duties.

The system needs amending to address the reality we find.

Having had 35 patents issued over the last 30 years, I agree with the first comment. Today, almost anything can be patented, even if high-school physics and common sense indicate that it will not work. Then there are patent trolls, who take issued patents, apply for a similar patent, get it issued, and then go to the original inventor and try to sue for a royalty.

Individual inventors, like another Edison, are at a huge disadvantage over lawyered-up trolls and large corporations.

Edison ruthlessly defended what he thought were his rights (e.g. using thugs to force movie studios to get licenses for all their cameras) and apparently stole a good many ideas from other inventors. He was more like the big corporation than an unknown individual.

Very true about Edison. Before Hollywood, the movie industry was largely in the North East. The reason why the movie industry set up shop in Hollywood was so that they could be as far from Edison as possible and also be close to the Mexican border if Edison still sent his thugs after them.

Having been a member of the U.S. patent bar since 1989, and worked with many Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) applications as well as many multi-national companies, I find the article somewhat interesting, but largely specious like most attempts of economists to understand invention, technology, and patents.

First, it’s a bit surprising that the authors, who work for the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) didn’t mention that WIPO administers the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) and PCT applications. Not that it affects the quality of the article (such as it is), but this piece is a bit of a plug for WIPO and the PCT.

Second, while the PCT bibliographic page does include the addresses and nationalities of the named inventors, one needs to be congizant of the limitations. The mailing addresses may not always be accurate—many applicant simply use the company address for their mailing address. And the applications don’t indicate who is on a temporary visa.

The fact is that the authors define “immigrant” simply as any named inventor whose nationality is different from their mailing address. Such a simplistic assumption doesn’t account for the practices of multinational coroporations that may transfer scientists and engineers on temporary assignments. Moreover, despite their assertions, this information does nothing to indicate why a particular inventor may have “emigrated”. As usual, the economists take some correlative data and stretch it past the breaking point to tell a just-so story that fits their dreams of market-based competition and compensation.

Third, as with all attempts of economists to write about invention and patents that I’ve seen, the authors rely on a simplistic association between patent documents, invention, and technology. All three are different animals. Patents and patent applications are legal documents that reflect the writing of the author (usually a patent attorney or agent) to obtain a desired result from a legal review (i.e., the patent office or a court). The language and subject matter in a patent application thus only partly reflect the invention; the document is a characterization of the invention in a legal context, especially since “invention” in this context is a legal term. So, the only way to understand the “technology” is to read the text carefully; and even then the results will be higly speculative.

Overall, the analysis provided by the authors is the usual specious work of economists. Yes, there are some potentially interesting correlations. But the sorts of conclusions the authors derive are not supported by the evidence they present.

Finally, to those expressing cynical views of patents and patent offices, I offer my experience of nearly 25 years working with examiners and inventors. Yes, I’ve seen some real howlers over the years. Yes, the patent offices and courts could do a better job. But by and large, most patents are reasonable, especially given the constraints on all of the parties.

I don’t think patenting life forms is reasonable. Why was that ever allowed? It’s going to get incredibly mucky once human DNA is involved. Worse, back in the 90s people were randomly generating GATC sequences on a computer and patenting them just in case they could be handy later, completely functionless gene sequences. Not to mention the heavy overlap of patented computer code which is bogging up into a ridiculous pile with trolling lawyers swimming on top.

Patents these days seem to hinder invention more than protect inventors. It’s just become a sandbox for lawyers to play castle.

I always enjoy Mr. Lentini’s comments, but I think that here he doth protest too much. It is certainly true that some inventors are in the United States on “temporary assignment”, but in my last job I shared several patents with the most prolific inventor in the corporation, who had been in the U.S. and exploited on one “temporary” visa or another for 15 years.

There remains much that can be said in defense of the patent system and patent attorneys. I’m afraid not much can be said in defense of the Court of Appeals of the Federal Circuit. Just as Mr. Lentini holds economists incompetent to evaluate patent law, I’m afraid I must hold the Federal Circuit incompetent to evaluate invention, or to distinguish invention from fantasy, where science is the distinguishing feature of invention.

When the first United States Patent Act was passed in 1790, information traveled at the speed of a horse-drawn carriage. Today, the Court must perform a Michelson-Morley experiment every time it attempts to rule on which art is prior. Even worse has been the Court’s decision to allow the patenting of software algorithms as “business methods”. In so doing it has replaced the scientific standard of replicable effects with the sorry standard of replicable profits.

Like the system that spawned it, much of the patent system has become a travesty. I believe the article–and Yves’ take on it–usefully demonstrate how one of the system’s sorriest outcomes has been its devaluation and commodification of science, scientists, and science education.

Thanks, Thorstein, for your kind words about my comments. I have a couple of thoughts to your reply.

I think your inventor example just illustrates my own point, that what the authors call “emigration” and their speculation about the factors for that emigration is based on faulty reasoning, because they cannot use the patent applications to identify the actual circumstances behind the differences in addresses and nationalities. Multinational corporations should have been at the front of their minds in their analysis.

I agree that the courts have had some serious problems over the years and still struggle. But don’t forget that courts decide legal questions, not scientific or technological questions; and courts certainly don’t assign or evaluate the value of any invention. Appeals courts, must accept the facts as found by the lower courts and patent office; they cannot do their own investigations.

Yes, we desperately need judges at all levels who are better acquainted with basic science and engineering concepts. We also just as desperately need a public that understand science and engineering too, since it’s public who compose juries and it’s the juries that find the facts in court.

We also need legislators who understand science and engineering and who will make laws to bring the economic and social effects of patenting into better harmony with society. Too often, Congress ignores this responsibility, often to placate industry, leaving the public with no choice but to seek various modifications to and interpretation of the patent law in the courts to find justice. While I sympathize with the problem, the solution in legislative, not judicial.

Interesting article. Not sure it says much other than this, the U.S. is a more hospitable country for new ideas at least within the realm of exploiting patents so why wouldn’t you want to move to the U.S. if you were an inventor?

Yes, the implication that since we draw in people from other countries do we really need to nurture our own population? Well the answer should be obvious of course not. There is no need to do anything with the population of the U.S. other than insure state/corporate control of the subject population. The elites around the world like to come to the U.S. because it is stable, orderly, and skewed for the elites with little consideration given to the lower orders of society.

As for the patent system, I think it is too focused on money and wealth. We need to move towards a new paradigm implied by social science that shows that large monetary rewards in themselves do not spur creative activity. We need to move towards a sharing culture or, frankly, we are doomed to create more of the same and that is simply unsustainable.

If folks can’t solve a problem, they try to isolate themselves from it. But, the causality goes both ways. I.e., the more they can isolate themselves from some issue, the more they’ll disengage from solving solvable problems. So, yes, I do think the availability of second-class labor gives businesses a way to work around the negative affects of not fixing education. (Similarly, voting tests, if enacted, would be another workaround.)

Slightly more generally though, US businesses want second-class citizens in any shape or form, because it’s easier/cheaper to exploit the more vulnerable. H1’s can’t take a better job offer. “Illegals” — why is the employ-EE called “an illegal” and not the employ-ER? — can be forced to go home any time. And people with mortgages and/or a lot of debt can’t withhold their labor in protest or take very many risks.

(Non-human) life forms were found patentable subject matter, because the Supreme Court found they met the definition of patentable subject matter. Patent law, like tax law, is amoral; it’s up to Congress to decide what sorts of inventions “should” or “should not” be entitled to a patent.

As for the random sequence business, most of those patents are worthless precisely because the sequences they claimed had no function (i.e., utility as required by law)—a rule that that the patent offices promulgated soon after that boom started. In short that game proved an expensive boondoggle for many companies, as was predicted by many patent practitioners (including myself).

As for “computer code” (you actually don’t patent the code), I agree that the courts and patent offices have made this issue far more difficult than it had to be. But the recent decisions by the Supreme Court and Federal Circuit (the next highest court for patent matters) will take much of the steam out of this phenomenon too.

One innovation I have argued for is a “use-it-or-lose-it” defense&msadh;if a patented invention isn’t actually made, used, or sold for a certain period of time, then the defendant should either have a complete defense or pay only a nominal royalty for any infringing activity until the patentee actually starts “practicing” the invention. That would blunt the desire of those who want to simply build paper portfolios and bring law suits.

Another innovation would simply be to increase the maintenance fees of patents so that holders would not be encouraged to sit on portfolios.

I meant this as a reply to direction.

Two thumbs up to ‘use it or lose it’

The political fear of change, which is usually technology-driven, has permitted patenting to remove new ideas from the scene.

Whether or not to file with PCT is an IP strategy choice that often has to do with which markets one is interested in (particularly Europe relative to the US).

It therefore seems to me quite likely that a nationality dataset based on it could have very strong biases in it.

I think it’s fascinating how economists take a question like “what influences the migration of inventors” and turn it into a terrible, aggregate-level statistical analysis. Maybe the answer to that question should be obtained by asking the inventors?

BUT NO! They must find some hidden variable using advanced statistics because otherwise they’re “not serious” and “might as well be a journalist.” So let me summarize my main problem with this column:

“Immigrant inventors” are those that engage in a costly and highly technical application for a patent while residing in a place other than their stated nationality. Not coincidentally, that would appear to describe STEM students from developing countries that engage in research while at developed country universities. **NEWSFLASH** Universities in developed countries attract students interested in research that leads to patent-able technology.

And yet, the authors don’t even mention educational institutions. Why? Because that’s not information contained in their data set (or at least I hope not, because otherwise it’s a travesty that they didn’t account for it). I bet that if you called up a random sample of, say, 100 of those immigrants you’d find that maybe 80% were (1) currently employed or a student at a university, or (2) recently graduated from a university that contributed to their patent research.

It’s a great topic, but just a small iota of thought about who an “immigrant inventor” really is would point the researcher toward the overwhelming role of developed country universities in generating patent-able technologies. This isn’t about patent law, because honestly, who would ever believe that highly technical differences in a highly arcane aspect of international commercial law would influence a large number of people to migrate? Answer, obviously only an economist.

The U.S. has a vary involved grant system where every government dept. DOT ,DOD, NIST etc …must Give so much money every year to develop new products and process ( Big Bucks). I think it was NIST who shelled out 100 million in grant money to develop the color green for led screens (now we have full color LED screens) to a small independent inventor.

All this information is readily available for people who look for it, The government also puts out a list every year of the type of new tech they are looking for. I think the US is about the only country that has such a large on going product development program in the world. It would be interesting to see how many of these inventor immigrants come to this country just to take advantage of this program ( which is a good thing). The ins and out of the program can be found under the SBIR/STTR grants on line. Even if you don’t get in the grant program they can direct you to other programs that you and you product might be right for. Been there done that.

Modern justice is purchased, not granted.

The fact of the matter is that a patent only gives you the right to sue. Nothing more. Most small inventors can’t exercise this “right” in a meaningful manner if their idea is stolen by an organization with more resources.

Any self interested inventor would be well advised not to bother with a patent for their idea, but to set up shop in another country where patent laws are either unrecognized, or unenforced, in order to protect themselves from well funded patent trolls like Microsoft, Apple, GE, and so on.

The implied question is whether our education system is being undermined by immigrant inventors. Maybe a tiny bit. But only in exceptional cases. Patents are temporary insurance policies so your idea can’t be stolen. And you have 20+ years to make a killing. And the whole system is close to a farce. The question for me is, Is commercial success destroying our education system? There are so many social reasons to study science, engineering, and the humanities. Explosive commercial success, much like the slower “productivity” paradox, doesn’t create a viable society. Only policy can do that. What we need are “lots of low-productivity jobs of high social value.”

Of course our education system from pre-school through post doc should be encouraged with government support. Education is a huge social value. And the thought occurred to me, since I’m so outraged by the plight of students with loans they can’t repay because they can’t get a job because jobs have been eliminated in droves by offshoring and other efficiencies (which should be felonies) … the thought I’m enjoying at this moment is, Why don’t we consider learning to be a job, just like teaching. If we value learning, we should pay people to learn shouldn’t we?

Because learning isn’t a job. Producing is a job.

This is an interesting article but has a big weakness: using PCT-based patent applications does weed out a lot of the small potatoes patents, but it simultaneously selects fairly strictly for patents filed by corporations. IOW, the patents in the authors’ study might have been developed by a corporation which then attaches a lab director’s name on the filing for formality as opposed to an individual inventor who comes up with an idea and then sells / licenses it to a company.

Why does this cause-effect matter? Because the authors’ premise is that attracting individual inventors to immigrate to your country will increase your R&D, whereas it might just be the case that having strong corporations with extensive R&D depts is the key to tech development, regardless of where they happen to hire inventors from.

Indeed, much of the migration patterns described in the article can be explained by the simple fact that the U.S. and Europe is where high-tech R&D gets done, so of course inventors have no choice but to emigrate there. Focusing on pay differentials underestimates the value of the overall R&D infrastructure.

To take a different example, the internal “brain drain” of promising tech grads emigrating from the rest of the country to the Bay Area is well known (the inventors of Netscape, for example, are Chicago natives who went to college at the U. of Illinois). Why do they leave? For the pay differential between Chicago and SF? Probably not. More likely because SF is where the companies (and the resulting surrounding infrastructure e.g. VC firms, etc) are.

On a slight tangent: IMHO, patents are a *cost* to society. They are a carve out of the public commons that is given to an inventor in exchange for his/her invention with the idea of incentivizing more such work. Our current system is failing in both ways: we pay too much for trivial ideas by granting patents willy-nilly in the software world (for example), and we devalue the worth of a patent to truly innovative inventors by designing a legal system that allows well-funded companies to easily abrogate patents held by small inventors.

I’m with Lune.

As an US born engineer my main concern for the US is maintaining it’s culture of admiration for creativity, as that is what has set us apart economically over the last century more than anything else except possibly “winning” ww2. Our education system needs to continue to promote creativity at every level.

As long as that culture is maintained in education and industry I have little concern over the country of origin of those who innovate here to our economic benefit.

Innovation is the one thing does really have a trickle down affect on economic prosperity and quality of life.

“Innovation is the one thing does really have a trickle down affect on economic prosperity and quality of life.”

I’m really curious as to how the internet, mobile phones and Tumblr have reduced poverty in the U.S. If you want to propose that they create jobs, in the U.S. you better have strong evidence that they create enough full-time, high skill jobs, where workers have a lot of autonomy, to keep up with the U.S.’ growing labor force. Customer service jobs at retail outlets should not be considered real jobs in your argument for obvious reasons. I think that an argument could be made that technological innovation, in recent decades, has concentrated wealth and power in the U.S.

How is the average person–not someone from the upper middle class–better off now than in 1989?

How is the average person–not someone from the upper middle class–better off now than in 1989?

They’re not. If you froze progress in 1979, the standard of living in US for an average person would be much higher today.

Take a look a California which has one of the highest poverty levels in US; it’s the center for innovation, entrepreneurship, venture capital and IPO kings. You would think there would be a shortage of workers to fill all those jobs created by foreign innovators?

I would venture that all this innovation activity centered in California is a net negative on the state: trillions of dollars alone were looted from US citizens by foreign IPO conmen during the 1990s tech mania.

Yup. I love the internet and the advances in computers (in part it’s how I make my living) but I felt a lot more optimism starting out in the late 1970s than I feel for my son today. And even then it seemed like there was less opportunity than what my parents had in the years after WW 2. When I was a kid my grandmother would talk about how hard life was when she was young and how much better it was now. My parents and I don’t have that sense of things today.

I am so impressed with the quality of the comments on this article and at NC in general. A pat on the back to all!

Inventors? hahahaha…HA! All of the inventors are in finance. You can’t invent anything without any capital and right now all of the capital is in the banking and finance sector.

It’s more than just inventors, it’s doctors & dentists & nurses & other sorts of professionals & technicians. Some other society pays for their education & training, but when these folks go to the US, they end up giving relatively little back to their countries of origin.

I am using much similar Aluminum Manufacturers, In Bangalore. , I thank you for the detailed information about this Industry.

Aluminum Manufacturers In Bangalore

i gone through your blog about Aluminum Manufacturers its really amazing. if you want additional information about Aluminum Manufacturers click here..

Aluminum Manufacturers