By Houses and Holes, who is a regular contributor at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, and The Drum and is a former commentator at Business Spectator. He is also the co-author of The Great Crash of 2008 with Ross Garnaut. He edits MacroBusiness. Cross posted from MacroBusiness.

Things are happening which suggest China is preparing for a period of slower growth and bank stress. First, from a note by Capital Economics:

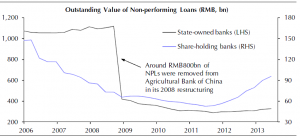

There has been an increase in the value of non-performing loans (NPLs) in the banking system since Q3 2011 (see Chart below), as the economy has slowed. At face value, this problem does not yet appear too serious, given that NPLs are less than 1% of outstanding loans, according to official data. However, the real figure is probably much higher. What’s more, the situation facing the banks is likely to get worse before it gets better, for three reasons. First, recent steps to liberalise interest rates will narrow the spread between lending and deposit rates, reducing banks’ profitability. Second, a large share of China’s local government debt, which is mostly owed to the banks, will probably go unpaid over the coming years. Third, the banks are heavily exposed to growing problems in the shadow banking sector, where the risks are already starting to pile up. Nevertheless, we do not anticipate a full-blown financial crisis, not least because the central government has the resources to support the banking sector if required.

How will they bail out the banks? More from Kate Mackenzie at FTAlphaville:

Earlier this week we wrote about how China is using its fiscal reserves to help retire some of the bad debts shelved off to the big “asset management companies” back in 1999 — with a big hat-tip to Chen Long, of INET’s China Economics Seminar.

Some more interesting news has been revealed by our colleague Paul J Davies in Hong Kong, who has a great story — two stories, in fact — about what Cinda and fellow AMC, Huarong, are doing.

[First, as an aside – we neglected to mention (and a few readers pointed this out) therecent WSJ report that one of the AMCs, Cinda, is gearing up for an IPO soon — perhaps later this year. This was in Chen’s original post and, as he pointed out, it just adds to the intriguing sense that the Chinese authorities are somehow wanting to clean-up the AMCs in order to prepare to recognise a newer round of non-performing loans.]

Anyway, Paul writes that there have been talks with big foreign banks — Goldman, Deutsche and Morgan Stanley — about investing in Huarong. It’s not the first time western banks have invested in an AMC. In March last year, UBS reportedly bought 5 per cent of Cinda, while Standard Chartered bought 1 per cent.

Meanwhile, Paul’s banking industry sources do believe these moves are all part of preparation to deal with the latest round of debt build-up:

Now, two of those AMCs, Cinda and Huarong, are raising fresh private capital in order to play a much bigger role in the next round of bad debts that are expected to emerge from the huge expansion in lending that has taken place in China since 2008.

Paul also quotes an analyst from CIMB who estimates the AMCs’ return on equity might have risen from 8.9 per cent in 2009 to 15.5 per cent last year. How that is possible, we have no idea — but here’s a clue:

After a rocky start, the bad banks have become adept at working out problem loans in only the past couple of years, according to bankers.

The four AMCs have extended well beyond their original remit of debt resolution — all own arms that “include everything from securities dealing to lease financing, insurance and private equity”, Paul writes — although the debt recovery is said by his sources to be the biggest source of income.

How the AMCs are really resolving the bad debts they are charged with is hard to know. Remember that the AMCs bought the banks’ bad debts in 1999 at face value — not how you’d necessarily expect to see a bad bank function.

We don’t know whether the Chinese authorities are planning to provide more assistance to help along the AMCs. But the assumption seems to be there that there will be continued state support, judging from a Barclays note cited by Paul back in March 2012. And when Cinda sold a stake to UBS and StanChart in 2012, it also sold a portion of equity to CITIC and to China’s National Social Security Fund.

Funneling fiscal resources towards repaying those bad debts just means the taxpayer, ie the already-financially-repressed Chinese householder, is the one who pays up.

So these bad banks are nothing more than tax-payer subsidised bailout machines. You might wonder why Western banks want to buy into them given by definition the returns must be lousy but why not given their potential returns at home are financially repressed.

So the Chinese appear to be readying a bailout mechanism. That implies three things. First they know that they will need one, which suggests strongly that are going to proceed with reform that will cause bad debts to rise materially. Second, it is likely to be accompanied by slowing growth for a period. And third, it is unlikely to result in an outright hard landing (barring a brief accident) as the banks will never be capital constrained.

Our final piece of evidence is a quote from Stephen Roach via the AFR:

Roach is a big believer in China’s urbanisation story. One of his favourite statistics is that in 1981, China’s urban population was just 20 per cent. Today it is around 52.6 per cent and by 2030, it is expected to reach 70 per cent. To accommodate that flow of people, China needs to build 100 new cities with a population of more than a million. As long as that is accompanied by strong growth of the services sector to provide enough jobs for the city dwellers and a better social safety net, that will not only keep investment spending relatively high but also boost incomes and consumption.

Roach became a true believer in China in 1997. As head of Morgan Stanley’s global economics team, he went there to understand how the Asian financial crisis might play out. “I had a hunch, nothing more than a hunch, that China held the key to the endgame to this crisis,” he says. “Not only did it quickly become evident that China was not going to succumb to the crisis, but I uncovered, at least in my own view, that they had a totally different approach to economic development strategy that allowed them to emerge from the crisis as the new pan-regional leader of a dynamic Asian economy.”

In the late nineties, during the Asian Financial Crisis, most Asian nations retrenched public spending, privatised assets and let banks fail, following the dictates of overly eager Western economists (at the IMF and elsewhere) including Tim Geithner and Larry Summers. The subsequent depression tore SE Asian economies (and political systems) apart.

On the other hand, although Chinese growth slowed, it ramped up its Keynesian stimulus and as the inevitable bad loans blew back into the banking system did not rush to liberalisation. Rather, they formed the government-owned bad banks describe above and took a step-by-step approach to development and the embrace of capitalism.

That is the key difference that Roach is referring to. So, what does that tell us about Chinese growth now?

First, China can keep spending on infrastructure but it will not grow like yesteryear. The approaching bad debts are several orders magnitude larger than 1999 and the need to rebalance is real. China slowed markedly the last time it went through this process and is already doing so again with more downside probable:

Moreover, the urbanisation story confuses rates of growth with levels (surely the most common mistake in economics). China’s urban population grew from 26% in 1990 to 53% in 2012 and total numbers of 710 million people, growth of roughly 430 million people in cities over 22 years. Chinese population growth is close to, or at, a demographic peak of 1.37 billion and if it were to grow to 70% urbanisation by 2030, that will mean 960 million total urban residents in 2030, another 17 years away but only another 260 million new people. The peak in growth in the urbanisation push is past and thus the industrial capacity required to build it is already more than adequate (at best, rapidly approaching so).

For Australia then and demand for its bulk commodities, China can urbanise its butt off and, in all likelihood, still generate flat or declining demand for infrastructure directed steel. There is no clear consensus on what portion of Chinese steel goes into fixed-asset investment but its somewhere between 40% and 60%, whereas consumption sectors account for between 5% and 20% depending upon who you ask. China might also take steel market share from elsewhere but that is not a net gain in production.

If adding all of that up gives you a big headache then welcome to economics. In my view it means the truth lies somewhere in the middle of the current debate. China can keep growing in the 6-7% range (with downside spikes if bad loans are mismanaged). But it will need to increase it’s consumption share of GDP. And demand for Australian bulk commodities is at its peak, excepting market share gains.

For a more detailed treatment of the AM companies and their role in the 1999 “bailout”, you can read the following:

http://www.amazon.com/Red-Capitalism-Financial-Foundation-Extraordinary/dp/1118255100/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1376991409&sr=8-1&keywords=Red+Capitalism

I strongly recommend Mr Pettis’ take on the urbanization “miracle” in his latest post:

http://blog.mpettis.com/2013/08/the-urbanization-fallacy/

In short, urbanization is not a leading industrial activity. On the contrary, it is pro-cyclic and won’t help to boost the economy when it is slowing down.

Great rebuttal.

It’s a dose of realism for the idealists who see state planning as a cure-all for everything that ails the economy.

Here’s the panacea, quoting from the article you cited:

Mexico offers a cautionary tale to such boundless theorizing. Following the Mexican Revolution in the second decade of the 20th century, the push was on to “modernize” Mexico. Part of that was forced urbanization. Forcing of the peasants from the land at times became an extremely violent enterprise. Here’s the result:

Needless to say, the forced urbanization did not yield the universal prosperity that was promised. It did, however, furnish a huge workforce that could be exploited at starvation wages, and spurred the growth of massive slums on the outskirts of Mexico City and other major Mexican cities. It was a boom for the foreign-owned Maquiladoras, who benefited from the surfeit of low-wage labor.

Unfortunately, globally, one of the products of forced ubanization has been the explosive growth of slums:

This leads into an entirely new area of inquiry, whether urbanization is sustainable or not, ecologically speaking:

It seems to me the sustainablility of the urbanization project is entirely dependent on the continued success of the Green Revolution. And without perpetual cheap and plentiful petroleum, how can the Green Revolution not have a rocky future?

Exactly. There is not a magic recipe, a kind of universal econosocial medicine that works to cure all econosocial diseases spreading everywhere. For another instance, let’s talk about the massive “keynesian” bail-out of banks in the US and in the EU. It has miserably failed in economic and social terms because it was based en the false idea that banks are the “circulatory system” of the economies. They could well be described better as unregulated rent seekers, frequently involved in predatory practices, that only by chance, would help to finance productive activities taking an ever increasing indecent toll for their exclusive rigths to create money. Banks have too much of a rigth almost without any duty. Well, the duty of rescuing banks rests in in the shoulders of unemployed and taxpayers.

The professor did not mention that 260 million migrant workers are already in the cities with jobs. They are ready to be urbanized. The Chinese goverment’s urbanizing plan is not so outlandish if you do not dismiss this fact out of hand.

Please, if you want to make an argument, explain your data. Your 260 million urban workers waiting for urbanization need a source and an explanation, particularly given the number of empty cities existing in the country.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324412604578515382905495900.html

http://www.ibtimes.com/china-now-has-more-260-million-migrant-workers-whose-average-monthly-salary-2290-yuan-37409-1281559

Please provide evidence if you argue why China’s numbers about migrant workers are wrong.

If you quote an article you’d better read or unterstand what is written on it. 262 million migrants is the cummulative number of migrants in decades of migration. Of those, only ten million migrated in 2012 as it can be calculated from the article. It is ridiculous to believe, as you seem to do, that China has yet to provide infrastructures and housing for those 260 million when they have been building a lot in the last decades. Also, what Mr. Pettis says in his article, is precusely that because of the slowdown, less jobs are being created in the urban areas. So, we can anticipate that the number of anual migrants will almost certainly be lower than those 10 million in 2012. Then, the already high chinese investments in housing and infrastructures will have to be reduced, not increased as the economy slows down. Such reduction will, almost certainly, contribute to worsen the slowdown not to counterbalance.

If what you said were true, then China’s current urbanization would have already reached 70-75%. Instead, the current urbanization rate is only 51-52%. Because of the restrictions of the Hukou system, migrant workers can not buy homes in the city,their children are not allowed to attend city schools, and they cannot have health insurance, pensions, and other welfares like the city residents do. They have to endure much more hardship to stay in the city than their city counterparts. China’s urbanization is not going to occure in vaccum. The Hukou system has to be eliminated for real urbanization to begin.

Arguing about the marginalisation of migrant workers in China is a different discussion matter that cannot be summarized in simple numbers representing percentages of urbanization. Urbanization depends on many socioeconomic factors, but no matter how many houses you want to build for migrants or the population in general but such activity depends on the wealth that other economic activities create and cannot substitute them to create more wealth(read the arguments in the link provided above). Pettis argues that urbanization, can help in a depressed economy but it is illusory to believe that it will help to maintain high growth levels in China when the rest of the economy (due to needed adjustments) will be growing at a much lower pace than in the last decades.

The fact is that urbanization is happening anyway, with or without Chinese government’s intervention. The only way to solve the problems of the 260 million migrant workers is to urbanize them. I do not think the Chinese government has a choice here if they want social stability in the long term, because the vast majority of these migrant workers is not willing to go back to where they were from.

I don’t have time for a dissertation or even a lengthy argument, but Pettis’s description of what’s driving the Chinese economy and his description of how it works flies in the face of Frank N Newman’s description of how things work in China, and the Chinese government’s approach to financing infrastructure and growth, in his book: Six Myths that Hold Back America: And What America Can Learn from the Growth of China’s Economy. (2011) From what Newman writes, Pettis doesn’t understand how the Chinese government finances these things; he’s using American processes to examine China’s, and they don’t apply. (Chapter 9 if you can read on Amazon)

Newman was the former Deputy Secretary of the US Treasury (1993-1995) and spent five years as the first American Chairman of the Board of Directors and CEO of Shenzhen Development Bank, China (2005-2011). He was also previously Chairman and CEO of Bankers Trust, and and other banks in the 80s.

Further, Newman writes about the urbanization issue:

I think you should search for Pettis’ biographic data and then read many more older posts in his blog. He has written a lot about arguments like yours.

Does anyone know what the money-men help us achieve? I found myself reading a mad book called Babylon’s Banksters in desperation the other day – almost sucked in until a code equating temples with radio stations appeared!

There are plenty of ‘slum clearance’ failures dotted round Asia where the new housing is built where there are no jobs. Are we crediting finance and the banksters with abilities they just don’t have, whether in China or elsewhere? Accounts are unreadable and unreliable everywhere – from the Cooperative’s reading of Britannia in the UK to our suspicions of massive national frauds – and the outcomes tend to be ghost cities not renewable power supplies and other kit people can use in better lives.

Mao was fixated with exporting China’s grain to build a navy to re-establish empire according to close sources and finance begins to look as megalomaniac and narcissistic. We use quite fantastic maths that boil down in use to a common settlement language and 24 hour P & L to justify pay now against what turn out to be future losses – but at the same time we can’t and don’t build sensible infrastructure in spite of a massive surplus of labour to do it.

China is perhaps best understood from casinos in Macau and the massive black money-flow there. Finance can build such edifices whilst withholding solar panels and decent wages. Its an old story.

Heres one of the few descriptive videos of the great leap forward I have seen in the English language. It has its fair share of propaganda since its a CIA video but take note of the 7 hr workday and that women would get breaks to feed there children vs today’s Russia and China.

I just don’t understand what the hell happened.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kBjpRpXVM6E