By Jie Bai, Applied Economics Doctoral Student at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Seema Jayachandran, Associate Professor of Economics, Northwestern University, Edmund J. Malesky, Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science, Duke University, and Benjamin Olken, Associate Professor of Economics in the MIT Department of Economics and CEPR Research Affiliate. Originally published at VoxEu.

Eliminating corruption is a central policy goal of policymakers around the globe. It is known that corruption is a barrier to economic development because it increases the costs and risk of business activity, and deters investment. This column discusses a new study analysing the opposite causal relationship – the effect of economic growth on corruption. Both theoretical and empirical evidence show that economic growth causes the amount of corruption to fall.

Lambert here: As the authors admit, this article does not address forms of “grand corruption,” examples of which would include accounting control fraud, the revolving door, cognitive regulatory capture, academic choice theory, and “campaign finance.” Could it be that as national income increases, bribes indeed decrease, but “grand corruption” increases? Note, however, that their “cost of moving”-based analysis would apply (or not) below the Federal level, as jurisdictions compete for “jobs,” put contracts out to bid, persons oil the wheels and grease the skids of commerce, etc.

Eradicating corruption ranks among the central policy concerns of economic development practitioners around the globe. Then-World Bank President James Wolfenson made the case for combatting corruption in a 1996 speech now known as the “Cancer of Corruption” address. In it, he spelled out a theoretical mechanism connecting corruption and poverty:

“Corruption diverts resources from the poor to the rich, increases the cost of running businesses, distorts public expenditures and deters foreign investors…it is a major barrier to sound and equitable development” (Wolfenson 1996, 51).

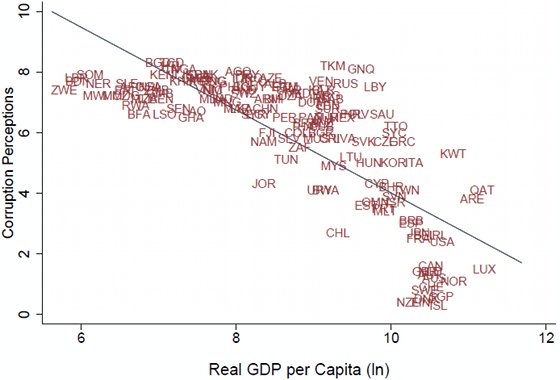

Indeed, regardless of whether analysts use perceptions of corruption data collected by Transparency International and the World Bank, or individual bribe payments reported on household and enterprise surveys, there is a strong negative correlation between a country’s per-capita income and the level of reported corruption (see Figure 1 below for example).

Figure 1. Cross-country relationship between GDP and corruption

Note: This figure plots Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI), which defines corruption as the abuse of public office for private gain on the y-axis. The CPI Score measures perceptions of the degree of corruption as seen by business people, risk analysts, and the general public and ranges between 10 (highly corrupt) and 0 (highly clean). The x-axis is the log of PPP Converted GDP Per Capita (Chain Series), at 2005 constant prices.

The traditional explanation for this relationship has been the theory articulated by Wolfenson above – corruption increases the cost and risk of business activity, thereby deterring investment and depressing growth that could have lifted citizens out of poverty (Mauro 1995, Wei 1999).

However, there is an alternative possibility that has received less attention among development practitioners and academics. The strong relationship between income and growth may result from exactly the opposite causal relationship – countries may be growing out of corruption (Tresiman 2002). Over time, economic growth reduces both the incentives for government officials to extract bribes and firms’ willingness to pay them. Some scholars of developed countries have discussed this possibility in terms of a ‘life cycle’ theory with corruption peaking at early stages of development and declining as countries industrialise (Huntington 1968, Theobald 1990, Ramirez 2013). However, there has been little work either testing for this empirical link from growth to corruption, or laying out the specific mechanisms that could generate the link.

In our paper, “Does Economic Growth Reduce Corruption?” we do just that. We provide evidence that economic growth causes the amount of corruption – specifically in the amount of bribes that firms pay to government officials – to fall. Our analysis takes advantage of subnational variation in both governance and local economic development within Vietnam, drawing on a unique annual survey of private domestic businesses operating in the 63 provinces of Vietnam. We then propose and test a theoretical mechanism that could explain why economic growth tends to lower corruption.

Our Theory: Firm Mobility and the Growth-Reducing Corruption

The key theoretical insight of our argument is that the share of bribes that officials will choose to extract as rents depends on a firm’s ability to move and set up business in a different location. Ask for too much, and firms that have the ability to do so, will simply pull up anchor and head to safer harbours. Because officials know this, they are likely to set a bribe amount that is just below the cost of moving.

Building on that insight, we show that as firms grow the cost of moving should decline relative to firm size. The fixed cost of moving becomes less expensive relative to revenue, and more and more firms have the opportunity to escape the bribe requests of officials in their locality. Corrupt officials faced with a sudden growth surge must lower their bribe rates, or face losing their key providers of employment and tax payers to competitors.

Of course, the benefits of growth are not experienced equally by all businesses. Some businesses are more heavily anchored to particular locations. Socio-cultural differences across locations, proximity to natural resources, previous experience, and limited property rights all work to constrain the mobility of businesses. Operations for which these constraints are most severe will be less able to duck bribes by moving, and will be singled out as targets by corrupt officials.

The theory we propose has important policy implications. To the extent this theoretical mechanism is important, rather than focusing on politically difficult institutional changes to combat corruption, resources might be better spent on policies that facilitate capital mobility across subnational jurisdictions. Providing clear titles to business premises, for instance, enables entrepreneurs to sell and recoup the full market value of land. Such businesses are more mobile than renters or owners with insecure titles, who risk significant losses if they try to escape corruption by fleeing across the border.

The Test: Subnational Data from Vietnam

The outcome that we seek to understand is the bribe rate, measured as firms’ reported bribe payments as a percentage of annual revenue. Consequently, we focus on the specific interaction between business managers and the government gatekeepers who have the ability to extract bribes. We calculate this from an annual survey funded by USAID and administered by the Vietnamese Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

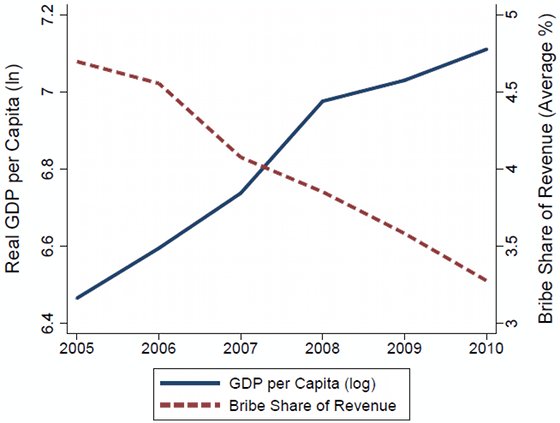

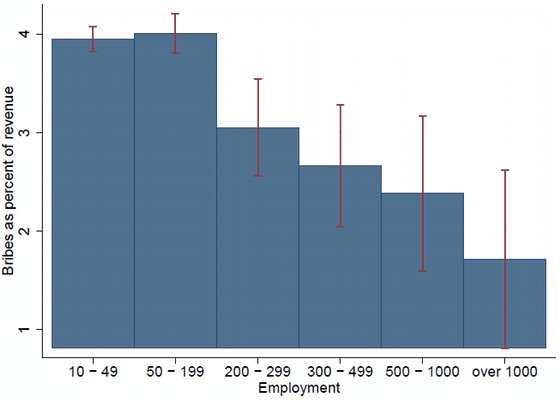

The survey has the particularly beneficial feature of seeking to compare economic institutions across Vietnam’s 63 provinces through an annually published Provincial Competitiveness Index (Malesky 2011). The explicit focus on the province is no accident. Due to a series of decentralising reforms, the interface between businesses and government occurs at the provincial level, including business registration, licensing, land acquisition, and inspections. Focusing on bribes paid to provincial officials accurately reflects doing business in Vietnam, but it also limits worries about the confounding effects of widely divergent national cultures and histories that have dogged work in the extant literature. Naïve analysis demonstrates the plausibility of our hypothesis. Figure 2 demonstrates that the average bribe rate decreases as GDP per capita increases. More compelling still, Figure 3 shows that large firms actually pay lower bribe rates, which is what our theory predicts. Firms with higher revenues are more put out by a high bribe rate, since it increases the amount of bribes they must pay dramatically. To retain them then, officials must push their bribe rate lower.

Figure 2. Time trends and bribes and GDP per capita in Vietnam

Note: This figure plots the real GDP per capita and the bribe rate paid by firms in Vietnam between 2005 and 2010. The bribe rate is averaged across all firms responding to the PCI survey in the corresponding year.

Figure 3. Cross-sectional relationship between bribe rate and firm employment in Vietnam

Note: This figure plots the mean bribe rate (bribe payment/revenue) for different firm size categories along with a 95% Confidence Interval.

Finding variation in growth, however, poses the next empirical hurdle. Since conventional wisdom posits that corruption reduces economic development, we need to find a way to isolate that component of economic growth that is independent of the influence of local institutions. To do this, we estimate an individual firm’s economic performance based solely on how its industrial sector fared that year in the 62 other provinces where the firm was not headquartered. To construct this aggregate measure, we use a census of firms conducted by Vietnam’s General Statistical Office (GSO) and calculate aggregate employment at the province-industry-year level.1

Results

Using this technique, we show that exogenous industry-wide performance is indeed a strong predictor of a firm’s performance. A doubling of total employment in the industry is associated with a 1.6-percentage-point reduction in the bribe rate, or about 42% of the mean level.

Moreover, the effect is more pronounced for highly mobile firms. The magnitude of the effect of growth on bribe reductions is 17% larger for firms in possession of a Land Use Rights Certificate, which facilitates the sale of their business premises. Similarly, the effect is 20% greater for firms that already have branch operations in other provinces, and therefore possess knowledge and experience that could facilitate movement.

These effects survive a battery of robustness tests and alternative specifications, providing compelling evidence that growth can directly reduce corruption.

Scope of Findings

This decision to focus on firm bribe rates limits the scope of our findings. Corruption has a wide variety of manifestations to which our theory does not directly apply.

- It is not clear how growth would affect petty corruption that is experienced by households, as they seek to comply with regulations and supplement poor public services, such as schooling and medical care.

- Similarly, growth may have divergent effects on grand corruption, such as kickbacks on government procurement and sweetheart land deals for elite politicians, as growth simultaneously increases mobility and the pool of resources available for rent seeking.

Further research is necessary to trace out the causal logic linking development to these other forms of corruption.

References

Bai, Jie, Seema Jayachandran, Edmund J Malesky, and Benjamin A Olken (2013), “Does Economic Growth Reduce Corruption? Theory and Evidence from Vietnam.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 19483.

Huntington, Samuel P (1968), “Modernization and corruption.” in Political Order in Changing Societies, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT: 59-71.

Mauro, Paolo (1995), “Corruption and Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(3), 681-712.

Malesky, Edmund (2011), “The Vietnam Provincial Competitiveness Index: Measuring Economic Governance for Private Sector Development,” Discussion paper, US AIDs Vietnam Competitiveness Initiative and Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Data available at http://www.pcivietnam.org/index.php?lang=en

Ramirez, Carlos. D (2013), “Is Corruption in China ‘Out of Control’? A Comparison with the US in Historical Perspective”, Journal of Comparative Economics, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2013.07.003>

Theobald, Robin (1990), Corruption, Development, and Underdevelopment, Duke University Press: Durham, NC.

Treisman, Daniel (2000),“The Causes of Corruption: A Cross-National Study”, Journal of Public Economics, 76(3), 399-457.

Wei, Shang-Jin (1999), “Corruption in Economic Development: Beneficial Grease, Minor Annoyance, or Major Obstacle?”, Policy Research Working Paper 2048, World Bank.

Wolfensohn, J D (2005),“People and Development”, in Voice for the world’s poor: selected speeches and writings of World Bank president James D. Wolfensohn, 1995-2005 (Vol. 889). World Bank Publications: Washington DC: 45-53.

1 See http://www.gso.gov.vn for more details.

“Eliminating corruption is a central policy goal of policymakers around the globe.”

Are these guys serious? Are they on drugs? Kleptocracy is the dominant political economic model of our age. It just plays out differently, has a different flavor, in different parts of the world.

About all I come away with is that in developing countries government officials predominantly prey upon businesses, whereas in developed countries, it is clearly the other way around. Businesses prey upon government. However, in both the developing and developed world, business and government loot ordinary people. I mean what is the effective difference between paying an official to get phone service and paying excessive and often hidden fees on say a loan or a credit card?

Is simple bribe taking a less sophisticated, more direct form of looting? As opposed say to the Congressman who is bought not by any money now but the expectation, if he plays ball, of pulling down a six figure salary as a consultant to an industry he is legislating on and has oversight of?

With you, Hugh.

The article states: “The CPI Score measures perceptions of the degree of corruption as seen by business people, risk analysts, and the general public.”

First, “perceptions” is not an exact measurement but a subjective one.

Secondly, how are the “perceptions” weighted in the CPI Score? I would doubt the general public’s “perceptions” are given much weight. Would “business people” and “risk analysts” include those who are themselves gaming the system? Most people I know are fed up with the rotten Western model of Demockracy.

Anyone recall Donald Rumsfeld’s admission that $2.3 TRILLION was unaccounted for in the Pentagon? That’s a lot of petty bribes! With additional financial trillions gone up in smoke in the US and no prosecutions, I would suggest that the measurement of corruption needs a new model.

Myself, I perceive that the US would be on the podium in any Corruption Olympics.

Yes, the myopic focus on petty corruption completely misses the forest of grand corruption. Seeing the US at the “clean” end of the scale in the chart, leads one to conclude that the foolproof way to eliminate corruption is to legalize it. Voila!

Capture theory and collective action problems are related to the idea of concentrated benefits and distributed costs.

There may be a few rough methods to quantify kleptocracy via wealth transfers due to public policy.

In a well regulated, competitive market, one would expect to see increasing supply and quality as prices decline or stay flat relative to the increase.

Given the charts on the medical article at nakedcapitalsm. What is the risk-adjusted spread between Mexico and the US? This could quanitfy the regulatory arb insurers and pharma are playing against the citiziens of the United States. A 5% increase in life expectancy for $6437 ($7290-$823) per year per person in your family. Now capitalize that over a lifetime. A simple perpeuity model will suffice $6437 / (6% discount rate – 2.5% growth rate) = $183,914. The arb for no increase in life expectancy: $7290-$3000 = $4290. $4290 / (6% discount rate – 2.5% growth rate) = $122,571.

Can one can fairly rationally say that politicians and healthcare lobbyists are transferring nearly $500,000 in wealth of a family of four in the US to a concentrated group?

Using this back of the envelope method, could one roughly quantify the wealth transfer ability of the Federal Reserve System (interest burden on Federal Debt plus interest rebates imputed of a US Treasury based lender of last resort)?

Could one roughly quantify the wealth transfer due to the Military Industrial Complex (defense spending as a % of GDP – 2% of GDP benchmark taken on a per capita basis)?

Could one use this back of the envelope method, one could roughly quantify the wealth transfer ability of the Trade Policy (Trade deficit versus balance at 0% of GDP benchmark taken on a per capita basis)?

Nice model, but it does not work in my personal experience.

Coming from Italy, my experience is that corruption is at its *highest* during boom periods (the 1980s), and decreases during economic crises.

The 1991-2 crisis destroyed incentives for businesses to play along with politicians. The result was the 1992+ “Clean Hands” operation which swept away all major parties – it was essentially a revolt of businesses against their patrons.

While the mid 00s were not a period of boom, they were surely better than the post-2008 period. In the same way, the 2008 crisis eliminated benefits for businesses to play along, and the result was a new series of investigations – the latest of which just put the government – yet again – in danger. Not to mention the whole Berlusconi thing which is too big to model.

The whole post-war experience of economic growth in Italy mirrors a continuous increase of corruption, with crises as the occasional spots of common sense.

Maybe the model in the article applies more to low-income countries, and high-income countries follow a different pattern.

Also, in Figure 1 I do not see much of a linear relationship: it looks more as if there is one main cluster of corrupt countries, pretty much regardless of GDP (compare Lybia and Zimbabwe for example), and another cluster of rich, honest countries.

What the authors of this post are hyping is nothing more than U.S. national mythology.

Here’s how the Christian theologian Reinhold Niebuhr explains it:

Good citation. Jefferson and others did view prosperity as a logical result of virtue and believed that a just society rewarded the just. Even Adam Smith understood the danger of his “doctrine” and he believed that a virtuous Scotch Presbyterian society was the sine qua non of his vision and, even then, he saw that his system had moral consequences on the individual workers.

Sadly, we have morphed, as Neibur noted, into a society that puts the cart before the horse. I’ve tried to explain that common morality is our collective problem not the greed of those at the top. Once common morality begins to change then the oligarchs will start to change.

Unfunded pension liabilities are the dark cloud on the horizon of state budgets; a cloud totaling $4.1 trillion dollars for state-administered public pension plans. Though they represent unavoidable fiscal debt, pension liabilities often slip under the radar when states tally up their spending, thanks to their status as “future payments” and accounting games.

Frank Keegan, editor of Statebudgetsolutions.org, on systemic widespread corruption in state and municipal pension systems:

“Public sector plans, such as those at the state, county and municipal levels, are not subject to funding, vesting, and most other requirements applicable to private sector defined benefit pension plans ….”

“Private pensioners can lose benefits, while public pensioners cannot. No matter how much politicians, fund managers, brokers, placement agents and other insider pension parasites loot and pillage public plans, taxpayers are on the hook for it.”

“State and municipal pension plans are perfect corruption machines at five levels:

1. Built in is the “moral hazard” of politicians making promises they know they don’t have to keep;

2. Then there is their unfettered power to lie and cheat in accounting value;

3. That lets them secretly drain pension funds as open-ended credit cards that don’t show up on the books;

4. The workers politicians betray have the power to keep putting them in office, and best of all;

5. Lack of pension transparency lets politicians secretly enrich contributors and cronies.

“If residents and businesses paying taxes to support this corruption machine and the public workers victimized by it want some insight into why politicians and pension insiders love alternative investments, take a look at the latest Maryland Department of Legislative Services Office of Policy Analysis Annual Retirement and Pension System’s Investment Overview of the State Retirement and Pension System and State Retirement Agency….

“Overall, since 2007 Maryland pension funds dropped more than $3.7 billion, leaving them $18 billion below where they promised to be by 2011. At the same time, pension obligations increased more than $5 billion. That is a death spiral. To one degree or another The People’s Democratic Republic of Maryland represents what is happening in state and municipal defined benefit pension plans all over our nation.

http://watchdog.org/14074/commentary-gao-pension-survey-reveals-endemic-corruption-hiding-in-the-hedges-2/

“One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken. Once you give a charlatan power over you, you almost never get it back.” ― Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark

What a load of crap! I can’t believe these people actually wasted time and energy with this nonsense, but then again we are talking about a PhD student, two economics professors and an associate professor of political “science”.

What you are describing here is akin to four elementary students getting together and deciding to write a short story about their understanding of the universe. While it may be entertaining, the utility value is about the same as the dog shit on the bottom of your shoe.

My reaction completely. This is the same crap I used to read in “development” reports I used to read because I thought it meant something. Here’s an example–what is the difference between the Mafia and Wall Street? To be clear, I know the wise guy culture or used to and had a small window to wise guys on Wall Street–not much difference except the culture and, more importantly, the scale of larceny. In social terms the Italian mafiosi are better company and more trustworthy.

Absolutely. It’s a veritable messianic political program which has succumbed to the utopian temptation.

There’s not a dime worth of difference between our free market madrasas and the free market Gestapo.

The authors of this article have embibed of the neoliberal Kool Aid, and when they speak of “corruption” what they are referring to is a subjective measure which is manipulated to demonize national leaders who decline to join the ranks of the “comprador bourgeoisie.”

The “comprador bourgeoisie,” according to Ljubiša Mitrović, is

The corruption trope falls generally under the age-old rubric of “The White Man’s Burden,” which

We are immediately tipped off to the fact that the authors are peddling a neoliberal “White Man’s Burden” agenda by the input data they use as the basis of their “analysis”:

But here’s the rub: Transparency International is nothing but the handmaiden of the transnational capitalist class and its comprador bourgeoisie, as Bill Black documents in a recent post:

Bill Black is far from being alone in questioning the integrity and impartiality of Transparency International:

And then there’s this:

Kevin Phillips in Wealth and Democracy notes that corruption comes in two varities. There is the blatant, “hard” type — bribery, embezzlement, fraud, swindling, etc. And then there is the “less obtrusive but at least as important” type, the “corruption of thinking and writing – the distortions of ideas and value systems to favor wealth and the biases of ‘economic man’.”

When it comes to the latter variety of corruption, nobody does it better than the United States. And this “study” and “analysis” are prima facie evidence of that.

When it comes to the latter variety of corruption, nobody does it better than the United States. And this “study” and “analysis” are prima facie evidence of that. -from Mexico

Nice comment and spot on conclusion!

Wow! I want to scream! (but I have to run to work)

The measures of corruption are completely (naively?) biased (I need to read this completely for the degree of the authors’ caveats). Consider QE, TARP, plugs (see Reuters’ miltary bookeeping http://www.reuters.com/investigates/pentagon/#article/part2). Grand scale corruption is not always in an obvious, measurable form (i.e., I experienced cash bribery in country “X”). Concealing and reframing is part of the purpose of PR; and part of our resposibility to be sceptical analysts, researchers, citizens and consumers.

Bottom line on this for me? The “data,” which appears to be from the Western Thought Foundation.

Figure 1. The centerpiece of your argument that so-called prosperous states have less corruption is a plot of the relative PERCEPTIONS of corruption? Do me a fave and ask the Koch brothers to chart themselves on that graph and you’ll see how much “perceptions” of anything are worth.

Figure 2, 3. The Vietnamese Chamber of Commerce and Industry has a “survey” of major businesses regarding how much they pay in bribes? Is this like a few decades ago when NY Mayor Rudy “the trains run on time (wait, no they don’t) Giuliani started that new police initiative, the “hey, did you commit any felonies today?” survey.

I want to blame naievete on this, but even in grad school I had the good sense to know when faculty advisors asked me about how my papers were going because they wanted to sleep with me.

Just what we need, more growth. More stores, more shoppers, more pressure on natural resources, more cars and more oil/gas usage …. more, more, more.

LIES

I have never seen such bitterness and constant spread of falsehoods all over the print and TV news. I respected Bill Ralls till he called Hillard—Dumb-Unproductive.

How many have called President Obama a Liar?

He does not lie. He may and does present false information. He did not intend to deceive.

He just presented inaccurate information.

Did Bush Lie on WMD?

No. Doug Feith presented doctored misinformation to him that he presented to the public.

He believed what he was given as has Obama on Affordable Health Care.

You lie when you have intention to misrepresent.

I am so sick of these attack agents in the Republican and Democratic parties.

Aren’t you?

I use the word malfeasance to distinguish intentional, conscious wrongdoing from unconscious, unintended mistakes. The dilemma involves plausible deniability.

Just in time for the Christmas Holiday Season, a movie all about corruption: AMERICAN HUSTLE.

This is the true story of ABSCAM, one of the colorful events of the 1970’s that delivers more accurate descriptions of the local political scene and the nationwide reach of favor buying from local pols than we usually get to see. Yum. Can’t wait.

The following is from the website:

http://www.congressionalbadboys.com/Myers.htm

——————————————————-

Michael Joseph “Ozzie” Myers

Democrat, Pennsylvania (1975-1980)

On October 3, 1980, the Honorable Michael “Ozzie” Myers became the first congressman, since the Civil War, to be expelled for Congress–and the first for official corruption. The vote was 376-30.

Several months earlier, Myers, then 37, was convicted of bribery and conspiracy for taking $50,000 in cash from an FBI undercover agent in the Abscam investigation. He got three years in the federal pen and fined $20,000. He was released before his full term had been completed.

Myers became a member of the Congressional Prison Caucus.

Myers, a former longshoreman with a tenth-grade education, was unrepentant and filed two lawsuits against both the Ethics Committee and the FBI.

Myers was caught on video tape saying this, while pocketing money from the undercover “sheik”: “I’m gonna tell you somethin’ real simple and short. Money talks in the business and bullshit walks. And it works the same way down in Washington.” True, Ozzie, but other members of Congress don’t like hearing the truth. [For other pearls of wisdom, check the Quote Board]

“Eliminating corruption is a central policy goal of policymakers around the globe.”

Oh, right! How silly of me to forget.

“Both theoretical and empirical evidence show that economic growth causes the amount of corruption to fall.”

The Bush II years proved that. And besides, Greenspan showed that laws against fraud in finance are unnecessary. Totally.

Fatal Flaws:

N of 1. Using an example of one instance to claim a global phenomenon is faulty reasoning. Vietnam is one country. This relates to a level of analysis issue.

Selective possible cherry picking of data. Why use the USAID measure instead of the validated Corruption Index? Why only examine the firm bribery component within the USAID and other surveys? Why examine only Vietnam?

Resource Power is the mechanism, not mobility. Large firms are more mobile because they have more resource and other forms of power and status.

Reversal of the direction of bribery. Larger firms may not bribe precisely because the provincial governments may bribe them to locate there as opposed to somewhere else. Did the authors examine whether larger firms receive bribes instead of bribing local officials. Would larger Universities have more leverage with local officials? Unhtinkable – for employees of large, high status instututions.

Have these assholes been to India. Every person (I mean it. Excluding women who don’t have fudiciary authority) in India has participated in some kinda bribery either from the giving or taking side. That is 1/4 of the world population. Corruption has increased ten folds with the economy improving. Its just they have gotten smarter.

There is one other corruption that is not mentioned. It is called Market Corruption, and consists of benign neglect by market oversight authorities of consolidation.

It is a well known fact that market integration leads to lesser competition, which in turn leads to “price stickiness” – a bona fide evidence of market price collaboration. Even if price fixing cannot be proven physically, it happens quite naturally.

And, of course, it is the consumer who pays though the nose.

This type of market corruption can result from a political philosophy, as has existed throughout the Reaganite Years over the past three decades. It consists of benighted wisdom of the kind, “The government that governs least governs best”.

Which is tantamount to, “Whilst the cat’s away, the mice will play”.

The US has trended towards market consolidation, as companies rush down the Learning Curve in order to both minimize cost and, by Mergers & Acquisitions, allows a concentration of market forces that diminishes competition. (Ala “Snow White and the seven dwarfs”.)

It has become very evident that the Department of Justice could take some lessons from the Brussels Commission of the EU. For instance, at least two or three times Microsoft has been inflicted fines for various transgression of EU market laws.

How often has that happened in the US? The one time that Microsoft had a judgment go against it that threatened to break up the company into separate units, that judgment was overturned by a superior court. And Microsoft went on its merry way.

Or how about the SubPrime Mess that led to the Credit Mechanism Seizure of 2008 (and the subsequent Great Recession of 2009)? Fines are being paid for illicit practices, but just who has gone to jail?

The US is far too lenient with its corporate Market Dominators. And then we wonder why we have a Trickle-up Economy … ?

Yes, because the world’s A-Number One underlying crucial problem is two-dong backhanders in Tam ắ-Lam ắ Thiêng Đồng. Armed with this revolutionary new science, the academic mentors of the bright-eyed and bushy-tailed Jie Bai will no doubt turn the gimlet eye of scientific inquiry to second-order problems like

* How does growth affect Jamie Dimon’s capacity to paralyze the world economy with macro-scale fraud and theft and then arrange impunity and a private office blowjob from the Attorney General of the United States?

* How does growth affect DoD’s ability to piss away 8.5 trillion dollars since ’96, poof, gone, with no paper trail?

* How does growth affect Florida’s propensity to prop up dotards in fake judge duds to help bankers steal homes with fabricated documents?

* How does growth affect the productivity of US legislators held to quantitative targets for exaction of corporate graft disguised as campaign contributions?

…well, maybe not.

Anyway the main thing is, a bright guy like Jie might have been the next General Giap. So before he could kick America’s ass again, the preeminent brains trusters of Wharton, Duke, MIT, and Northwestern intervened and pacified him with busywork.

@Peace With Honor, Lafayette is absolutely right (below). You should be ashamed of yourself! What gives you the right to associate perfectly innocent Blowjobs with such scum as the Attorny General?

This is HIGHLY DEFAMATORY commentary and unfitting for debate.

There are other ways to insinuate what you mean. Clean up your act …

Indeed. “Full service” would have been both more accurate and more suitable for a family blog like this one.

As a geographer who has been writing critically on the economistic school of corruption with my colleague, Ed Brown, for a number of years now (see for example our piece ‘Shadow Europe: Alternative European Financial Geographies, Growth and Change Vol. 38 No. 2 (June 2007), pp. 304–327) there are severe problems in writing on corruption in this fashion, to do with not merely the way that economists envisage it in a classical/orthodox fashion, to the way that TI’s perceptions index has been developed as an ideological construct.

I am currently involved in some collaborative discussions on measuring corruption with TI and I have to say that this really has very little to say about ‘real life’ corruption because of the underlying assumptions it makes – the devil is in the ceteris paribus assumptions. I would really weclome the chance to write a reply and counter-factual to this…? Anyway.