By Lambert Strether of Corrente

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

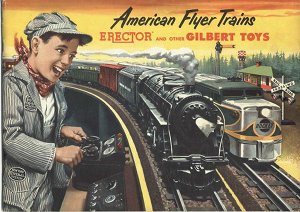

When I was 8 or 10 years old, my parents gave me an A.C. Gilbert “American Flyer” S-gauge train set for Christmas. That was a big deal for me then, and I’ve come to realize (many years later) that it was an even bigger deal than I thought.

“The trains” themselves were magnificent; the (steam) engines had cast metal bodies, and real heft and mass as they chuffed and rattled round the stamped metal track at high speed on two rails (unlike their crassly larger and ill-proportioned Lionel O-gauge rivals, with their toy-like three rails (though John Armstrong would surely disagree)). My father and I — the horrible word “bonding” would not yet have been used in this context — would turn off the lights and watch the trains throw shadows on the train room wall, cast by the brilliant red and green lamps from the switches, the glow of the transformer, and the locomotive headlamps and the lit-up caboose, all on the layout table he put together out of 2×4’s and Homosote (to dampen the sound!).

“The trains” themselves were magnificent; the (steam) engines had cast metal bodies, and real heft and mass as they chuffed and rattled round the stamped metal track at high speed on two rails (unlike their crassly larger and ill-proportioned Lionel O-gauge rivals, with their toy-like three rails (though John Armstrong would surely disagree)). My father and I — the horrible word “bonding” would not yet have been used in this context — would turn off the lights and watch the trains throw shadows on the train room wall, cast by the brilliant red and green lamps from the switches, the glow of the transformer, and the locomotive headlamps and the lit-up caboose, all on the layout table he put together out of 2×4’s and Homosote (to dampen the sound!).

All the time, of course, I was learning lessons: I could mow lawns or shelve books in the library to make money to buy trains (and kits and buildings and balsa wood and glue and paint); I could solder and saw and cut and drill and wire stuff up; I could imagine a world much like our own, but mine; and even more importantly, I could build a system. This last may be that’s why former model railroaders are so heavily represented in the technical community. From Steven Levy’s Hackers, which describes the seminal role the Tech Model Railroad Club played in the computer revolution that’s going to end by talking all our jobs away so we can live by plucking food from edible forests in our home towns except not because free markets:

The clubroom was dominated by the huge train layout. It just about filled the room, and if you stood in the little control area called “the notch” you could see a little town, a little industrial area, a tiny working trolley line, a papier-mache mountain, and of course a lot of trains and tracks. The trains were meticulously crafted to resemble their full-scale counterparts, and they chugged along the twists and turns of track with picture-book perfection.

And then Peter Samson looked underneath the chest-high boards which held the layout. It took his breath away. Underneath this layout was a more massive matrix of wires and relays and crossbar switches than Peter Samson had ever dreamed existed. There were neat regimental lines of switches, and achingly regular rows of dull bronze relays, and a long, rambling tangle of red, blue, and yellow wires twisting and twirling like a rainbow-colored explosion of Einstein’s hair. It was an incredibly complicated system, and Peter Samson vowed to find out how it worked.

The Tech Model Railroad Club awarded its members a key to the clubroom after they logged forty hours of work on the layout. Freshman Midway had been on a Friday. By Monday, Peter Samson had his key.

Peter Samson fell in love with the wiring, and I suppose if I had done that, I would have become a real software engineer, instead of the somewhat competent coder that I am today. What I did fall in love with, though I wasn’t aware of this until years later, was a magazine that my parents got me a subscription to: Model Railroader. From Model Railroader, and its editor, Linn Westcott, I learned, all unawares, how to structure a publication into departments; that errors, from typos on up, were not to be tolerated and should be acknowledged; that reviews were there to serve the reader, not the manufacturer, and so could should be critical;** and even — I swear that Westcott used em dashes like this — prose style. Westcott also laid the magazine using the apparatus of a technical publication, with tables, figures, diagrams (especially circuit diagrams), callouts; apparatus that possibly, I now think, served as a shield for men ridiculed for “playing with trains.”

That Model Railroader had the air of a technical publication was also important — and here we’re getting into the [de|e]volution part — because the highest expression of a model builder’s art was, arguably, “scratch building” a detailed replica of a steam locomotive in brass or nickel silver, while actually fabricating all the components oneself; at that time, in the late ’50s to mid-60s, we could actually build stuff, and there was story after story about men — Westcott unashamedly used “men,” or, informally, “fellows” — actually building tiny machine tools to construct wheels, boilers, cylinders, valve gear, and so forth. The layout were important, although “picture-book perfection” (see at right) is not very much like modeling when it comes to issues of scale and scope, of a railroad instead of a locomotive, but the miniature machinist was at the pinnacle.

Fast forward forty years, and all that is gone, evolved or devolved I am not sure. Then, before the neo-liberal dispensation had begun walk out of the station, in the mid-70s, and now, when it’s heading, at top speed, who knows where, but probably to ruin. One thing that is evident to me now, that I could not see as a child, is how class intersects with the hobby: One must achieve a certain station in life to have permanent housing with the space for a large layout, and the money to spend on lots and lots of locomotives and rolling stock.** A big layout can take a decade to build; the hobby is not one for the downwardly mobile! And now, with wealth, one can even buy a museum grade layout from any of a number of builders; such a thing was unheard of when I was a child. Another change, which may also express class (“…nothing more, and nothing less, than groups of friends…”) is open expressions of friendship between men; where Westcott fictionalized friendships in the “Bull Session” Department**, today, friendships are openly expressed: Men build models for each other as gifts, exchange rolling stock, set up interchanges between their (fictional) railroads, create space for model railroaders who’ve had to downsize their homes, and so forth. Bonding, in other words. And third aspect of class is that we, in this country, are privileged to purchase models with absolutely fantastic detail — eye candy of a near-pornographic glaze — all “factory applied” by tiny fingers somewhere in Asia. (When I was a teenager, “detail” was synonymous with brass locomotives, scratch built, but also constructed in Asia, but in Japan, and then brought to this country by “Pacific Fast Mail.” Mail! Can you imagine!)

So, as far as the locomotives and the rolling stock — surely the essentials of a railroad — what we once could make for ourselves is now made for us. Is that devolution? Or simply the workings of comparative advantage?

What we do today, and brilliantly, is model the entire railroad: We actually fill out the paper forms and “operate” the railroad more or less prototypically, even — here we find class again — modeling (reproducing) the social relations that make the General Code of Operating Rules come alive (leaving out the Jay Goulds and Jim Fisks, of course). And we model the landscape (the “scenery”) infinitely better today than we did forty years ago, although we model the contours of the land by carving pink slabs of (petroleum-based) styrofoam, spraying electrostatic (petroleum-based) model grasses, gluing down the track with caulking guns like Martha Stewart, instead of using metal spikes for pity’s sake…. And yet, for all the power of the illusion, especially the photographed illusion, I can’t help but be reminded, when I think of today’s scenery building techniques***, of the styrofoam pediments in the McMansions we built during the housing bubble before the 2008 crash; the houses were fake, because they were cogs in a giant machine of accounting control fraud. Isn’t there something fake about these techniques? Sometimes, when I see structures with too much detail — especially “pre-built” structures — I’m reminded of the horrifically sentimental Thomas Kinkade, “painter of light.” I hate having my heartstrings tugged, which strikes me as another kind of fraud.

Back to the timeline: The changes I’ve been describing encompass the neo-liberal revolution book-ended by Nixon and Obama. Somewhere along the line, we traded our ability to fabricate metal for the ability to fabricate a scene. Is that evolution or devolution? I’m not sure. If I had a son, I’m not sure I’d give him trains today.

Oh, and there was no such thing as “sponsored content” in the world of Lynn Westcott. He wouldn’t have stood for an “innovation” like that. Nowadays, I guess, we’re easier, more corrupt; and surely, in that aspect, devolved. MR doesn’t do sponsored content, fortunately, proving that the old way still linger and culture can be strong.

NOTE * A useful set of skills and attitudes if one wishes to end up blogging for Naked Capitalism!

NOTE ** I did not know that Westcott was an operator on John Allen’s Gorre & Daphetid (see image above); as an editor, he had effaced himself, another valuable lesson that vandals like Tina Brown would have done well to learn.

NOTE *** For his brilliant Miami Spur, Lance Mindheim will photograph a building’s wall, catching all its weathering, coloring, and detail, and then laminate the image onto a model building and voila! In the old days, the wall would have been built, detailed, and weathered manually. Mindheim’s layouts are beautiful, but again, I can’t help but think that a better crafted illusion has devolved the modeling skill.

What you have touched upon here, Lambert, has a lot to due with the very real and disturbing fact that “We’ve Become a Nation of Takers, Not Makers.”

More Americans work for the government than in manufacturing, farming, fishing, forestry, mining and utilities combined.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704050204576219073867182108.html?mod=googlenews_wsj

“Today in America there are nearly twice as many people working for the government (22.5 million) than in all of manufacturing (11.5 million). This is an almost exact reversal of the situation in 1960, when there were 15 million workers in manufacturing and 8.7 million collecting a paycheck from the government. It gets worse. More Americans work for the government than work in construction, farming, fishing, forestry, manufacturing, mining and utilities combined. We have moved decisively from a nation of makers to a nation of takers. Nearly half of the $2.2 trillion cost of state and local governments is the $1 trillion-a-year tab for pay and benefits of state and local employees. Is it any wonder that so many states and cities cannot pay their bills?

Every state in America today except for two—Indiana and Wisconsin—has more government workers on the payroll than people manufacturing industrial goods. Consider California, which has the highest budget deficit in the history of the states. The not-so Golden State now has an incredible 2.4 million government employees—twice as many as people at work in manufacturing.”

In this post there are more misrepresentations, propaganda misdirections and logical fallicies of the Corporatist kind than NSA can count on all their computers. I knew we should have driven a wooden stake through Ayn Rand’s heart.

Someone should invite Cynthia out for a stake(sic) dinner at the Silver Bullet Stake House.

I disagree somewhat. I don’t think the change in the ratio, especially if it’s as extreme as Cynthia says it is, is unimportant. I’m not against the way government functions have grown, as they tend, a lot of times, to serve all. They tend, often, toward civilization, though they’ve sometimes been known to be overbearing, the downside that libertarian-types focus on. The decline in manufacturing in the US, however, is cause for grave concern, IMO. My takeaway from all the discussion I’ve been reading since about ’09, is that economically, bottom line, it’s the current account balance (Isn’t that another term, more or less, for trade balance?) that’s killing us (the US).

Even libertarians can make important points, whether or not they were exactly the ones they intended to.

@Cynthia

Even if it’s true — and it will take more than a WSJ opinion piece to convince me of that proposition — so what?

Perhaps you have a solution to the problem of surplus labor in this country.

Let’s hear it.

There is no such thing as surplus labour because labour is not alienable; that’s like saying there is a surplus of imagination or love.

There is a “surplus” of labour power, a market failure, you might say, unless given one’s interests — human rental on the cheap, for example — the market were deemed to be a success.

Regardless, what is Cynthia’s solution?

Shorter life expectancy will take care of this problem over time, no?

Cynthia & WSJ have lied to us by comparing incomparable numbers.

The US population in 1960 was aprox 185 millions. Today it is aprox 320 millions. They should not be comparing absolute numbers of workers. They should comparing proportions of workers to total population. They must also adjust the proportions to compensate for the fact that few women in 1960 were allowed to work outside the home.

Since they have lied to us about which numbers to compare, I must distrust the numbers themselves. Who have they counted as government worker? Who as manufacturer?

Why have they not focused their disapproval on the absolute decline, and proportional implosion, of the number of jobs in “construction, farming, fishing, forestry, manufacturing, mining and utilities combined”?

Model trains just keep rolling…

Trains tap into something deep in our collective memories.

“Yet there isn’t a train I wouldn’t take, No matter where it’s going.” – Edna St. Vincent Millay

Hamburg, Germany’s Miniatur Wunderland is the world’s largest model railroad.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miniatur_Wunderland

Miniatur- Wunderland’s tracks add up to over 42,000 feet long. It has over 900 trains and thousands of cars and truck that travel through the eight completed sections. A light control system provides a simulation of day and night. It takes 46 computers to control the trains, planes, ships, and automobiles and other animations.

Taking hundreds of thousands of working hours to create, it is a work still in progress. The current large expansion project is expected to be finished in 2020, and will bring the total cost of this train set to over 26 million dollars!

http://www.miniatur-wunderland.com/

I was at a family reunion a few years back and my mother-in-law had bought kites for the kids to play with. Having actually built kites from all-wood “kits” back in the late 60’s I was intrigued as to the state of the technology. All that is required is to slide 4 sticks into a plastic hub and attach the plastic sheet and tie on the string (at least that is what the instructions said). There were about 5 fathers trying to do this, all of them younger than me by not by a lot, and none of them could assemble their kites, as their children started to lose interest in the whole project.

I noticed a flaw in the instructions when assembling one of the kites myself, but was able to get on up in the air pretty quickly, which probably put more pressure on these confused dads that had never seen a kite up close, let alone build one or understand how it works. I helped the father with the most interested son put theirs together and launch it into what was a decent wind for a NW Indiana summer day.

Within half an hour the kites fell apart (the plastic piece wasn’t strong enough), and all the kite kits ended up in the same trash barrel.

I thought back how my 1969 kite, which cost me a weeks allowance, spent a winter in the corner of my room and was used multiple times until one day the string broke (I had more than 500 feet of it out) and it sailed into the next county.

The desire for quality, the ability to fabricate things, to understand how they work; have we lost these in less than 2 generations?

When I was about 10, in Eureka, CA, on a clear summer’s day (not many) it would be windy as heck. I would take 15 cents to Herb’s store and buy a kite. I’d take it home, assemble it, the 2 sticks with the paper face or wing. I’d tear up some rags from my mom’s rag drawer, and tie them on the bottom and attach the roll of string. Then I’d carry it all up to the school playground. I’d fly that thing for a couple of hours. It would be hanging way out over the park across from the school. Fifteen cents, a little building, adjustment, for a ten year old those things flew perfectly. I remember the cheapest balsa-wood gliders were the best flying ones, too.

Wow! Buying kites? You guys were obviously in the upper class. We used to make ours out of newspaper and sticks bought at the craft store, sometimes we’d try reasonably straight branches. We’d use nylon fishing line because we lived in the country, outside of El Centro, CA, and wanted to go really high. The Blue Angels used to fly over our house and my dream was to get my kite high enough for them to see it.

A Yorkshireman, I see….

http://youtu.be/Xe1a1wHxTyo

Just before the forsythia blooms, cut a couple of likely stems and tie with thread into your favorite shape. Cover with tissue paper wrapped and glued around the stems. Paint if you like. Tie the dihedryl right with a little practice and add a tail and string.

They, also, usually don’t last more than an afternoon. Ah…the joys of spring.

Be nearly 65 and hing been in radio and electronics and computers since I was 10 or so, I remeber those times when “Made in America” meant something.

Sometime in the mid 1950s – when the owners and engineers were systemattically replaced by bean counters – is when the quality of American products started to take a nose dive.

By the late 1960s the quality was nearing bottom. Making it so much easier for the Japanese and Euopean products to take over. The indroduction of Sony’s Trinitron was the death kneal of American color TV. Most home audio makers – HH Scott, Harmon Kardon, Fisher, Dynaco etc. – were being madin in Japan.

The test equipment makers were still doing well and puitting out very good stuff, as well as the equipment for commercial users. But even they were slowly being replaced by better and cheaper foreign products.

As soon as the bean counters got control of the company, the company went into the toilet.

It happend every time.

Yes. Companies are started by people with a passionate interest in what the company is doing. But as the original owners retire or die the companies go into the hands of big money guys who only care about maximizing monetary return. Quality becomes a cost to be minimized.

Wonderful post, Lambert, and a terrible touch of nostalgia for those of us who grew up in the 1950s making model train cars and model airplanes. It was a world of imagination brought to life by little more than a story in Model Railroader. My train world was a world of imagination fabricated from a few cars and a length of track, but it semed real enough. You could make a little go a long way back then.

I loved this essay, Lambert. Like most of your stuff it takes a few minutes to sink in. Our national love affair with trains is a good metaphor for our weakness toward fantasy. And model trains being a piece of nostalgia from the past are a perfect way to point out that the world has evolved beyond a capacity for indulgence. It will be harder to give up the idea of a boy and his train set than to actually give up the old train set now in the attic. But we really do need to give it up. Our lives became too precious, all fleshed-out with symbols of hope and comfort. And now is the time to change. Change the ties to old nostalgias and look to the future.

I don’t think those have been /lost/, so much as they have been made as unnecessary as possible at every turn. I’m much younger than that, but I have a rough parallel to the developments you remember, just with computers.

As a kid, I basically had to learn english just to play a game, I had to constantly learn, first to figure out how to work with terminal-style (DOS) OS’s, handle memory management tweaks, build my own rig from components etc. But all that is now gone. Not that I really miss many parts of the old systems, I fully recognise the foolishness of feeling nostalgic for the piss-poor excuses of computers of those days. But never the less, I still have this feeling of loss when looking at my sisters kids and the extra smooth ride they get, with touchpad gizmos that are trivial to use, trivial to the point of not requiring any effort at all except to sweep a finger here or there.

Is this just nostalgia, or have we actually lost something? I honestly cannot say, but I do have to admit I still feel the constant need to build something, even if it’s just on my computer. Never really had the chance to work that much with real life things, even though I’d probably enjoy it.

So, the more we make things easier to use, the most we lose the ability to NOT blackbox everything into these ready-made parcels of functionality. On the other hand, the process DOES allow us to do “greater” things, since we don’t have to pay so much attention to the ground level. Maybe that is the fundamental problem we have to begin with?

Or just pain trivial.

For the past few years the

kidsMakers have been doing “physical computing”, exemplified by its most common embodiment, the Arduino: a quite modest single-chip computer with horsepower on the order of a Sinclair ZX81, plenty of general-purpose I/O connected to a standardized expansion form factor, an easy-to-use development environment that doesn’t interfere too much if you want at the bare metal, and a strong ecosystem of usual and unusual modules (software and hardware) to interface all that GPIO to observe and affect the physical world.I’m not super keen on some parts of the community; people more oriented toward commerce and solutions than sharing and solving are well-represented in some quarters (MakerBot Industries’ conduct and behavior around their acquisition by Stratasys includes particularly outrageous cases of stealing from the commons via letters patent and plain old arrogation). But if the broader movement does get people thinking in terms of systems, stepwise cause-and-effect, and an ethic of creatively reusing things in ways they were never intended (rewrite people for the consumer fetish object’s story, if you will), more power to them.

You are 100% right and I should have thought of the Makers.

“The desire for quality, the ability to fabricate things, to understand how they work” – none of this is lost. One just has to be able to be specific about wanting and seeking them. Maybe there has been a time quality was automatically good. I seem to have operated from this assumption, but have had to abandon it quite a while ago. Now one has to know what quality is and inspect carefully to find it. This will expose many who do not have any idea about what quality means or how things work mechanically. They’ll just be mystified at why things refuse to work. Of course, finding out how things work is not fashionable or cool. And that has its own consequences. But if one views the goings-on as a project to separate wheat from chaff, everything is going perfectly.

“You can’t hammer a nail over the internet”, Matthew Crawford reminds us in Shop Class as Soulcraft.

I’m so glad my son is an electrician with a considerable portfolio of other construction skills. A lot of his work these days is from google heads, twitteratti and facebookees and the like who are buying up grand old buildings in need of refurbishing (wiping out previously affordable, if somewhat substandard, housing for the lower income folks). I like the fact that what he does has physical presence that may last for years as opposed to the ethereal trivialities produced by the new richie ritches he works for. On the other hand, they own the buildings he has made safer, more comfortable and more beautiful.

As for hobbies, they are primarily fishing and motorcycling. A really material guy working and having fun in a material world.

Daughter, on the other hand, sits at a computer all day producing lighting effects for animated films. She makes a lot more money than my son but so far as I can tell is no happier for that. She’s really an artist rather than a computer geek and her appetite for a more robust connection to the material world takes the form of returning to the old ways in her spare time, producing images on paper with charcoal, ink and paint.

Lambert, I really enjoyed your story and the comments it inspired. But, I followed up on one of the past week’s commenters and have gotten “The Octopus” by Frank Norris. In it I have discovered a wonderful author and, let me say, a different view of trains. The way he introduces his first rolling train is a single engine making up time to Fresno at night, “a locomotive, single, unattached, shot by him with a roar, filling the air with the reek of hot oil, vomiting smoke and sparks; its enormous eye, cyclopean, red, throwing a glare far in advance, shooting by in a sudden crash of confused thunder; filling the night with a terrific clamour of its iron hoofs.” The sight and sound of it startled his main character from his thoughts as he was working his way back home, and after the train passed he became aware of terrible sounds of agony. The train had blasted through a herd of sheep that had escaped their fences and were crossing the tracks. Where he’ll go with the railroad in this story has certainly been evocatively foreshadowed.

http://www.msichicago.org/whats-here/exhibits/the-great-train-story/video/

Never read Model Railroader but the editorial integrity/standards were common across all the Kalmbach railroad publications–David Morgan the editor of trains way back when was a prime driver. Politically, the whole neo-liberal movement in America has a critical RR connection, since the first deregulation target was the obsolete ICC regulation of rails. (Airline deregulation was 2nd, banking 3rd) The restructuring of the bankrupt Penn Central was one of the greatest industrial interventions by the federal governmnet in history. Everyone involved was liberal, many were Democratic. The hijacking of sensible deregulation by the objectivists and class warriors came later, but the willingness of mainstream liberals to embrace the later, uglier neo-liberalism was due to its clear initial sucess in the transporation arena

Ah, David Morgan! Trains is sadly decayed. The photos are still gorgeous, but the CEO hagiography is cloying, and the neoliberal agenda sadly evident — glorifying EMD’s shutdown of London Ontario and subsequent move to non-union Muncie.

No! I’ve been reading Trains for over fifty years, and it’s better than ever. Kalmbach had the sense to fork the old-time stuff to “Classic Trains,” and today’s Trains tells us a lot more about how railroads actually work. They are a bit stingy about always trying to sell us access to additional stuff on their web site, but the physical magazine, and their web news and blogs, are quite informative.

“that errors, from typos on up, were not to be tolerated and should be acknowledged”

You got an extra “.” and space(s) at the beginning of graph 2

I have no idea what’s going on with the astericks

I wonder if you have any train games/sims you like? Days of Wonder’s “Ticket to Ride” is now available on Steam / tablets!

Why, thank you! The asterisks are notes — pretty conventional in the blogosphere. I like my trains physical, not digital…

things you cant do with a keyboard:

http://classic-motor-cars.co.uk/assets/2011/12/Linder-Story.pdf

http://www.classic-motor-cars.co.uk/restorations/jaguar-e-type-lightweight-%e2%80%9clindner%e2%80%9d/

trade skills will forever have a market, from the glass half full perspective.

Ya, the idea for the model train is a good one. If they didn’t have that, where would they have got the idea for a big train?

grin!

Brings back fond memories of being 8 years old in Parma, Ohio.

My Dad and I had a very rudimentary 4×8 HO layout down in the basement, but I remember visiting a friend’s house in Brooklyn (between downtown Cleveland and Parma) and being knocked off my feet by how professional and detailed his Dad’s layout was down in their basement. It was Magical!

John Allen’s layout was unbelievable, and still is.

God help us if we lose the natural drive and ability to make things with our very own hands.

Totally agree that American Flyer was far superior to the much overrated Lionel.

Powerful story that captured the essence of what has occurred on several levels. Thanks, Lambert.

… “Globalization” and “offshoring” is a story of betrayal, loss of child-like innocence, loss of trust in so called “leaders”, loss of independence, loss of much technological and manufacturing prowess that – as former Intel CEO Andy Grove said – drives innovation, elevation of the “services” sectors (especially finance, with all that has entailed), concentration of power in large banks and transnational corporations, massive wealth transfer, and destruction of the Western middle class… and the genie cannot be put back in the bottle, which was the intent all along.

So, where do we go from here? Anyone seen Godot?

Our hellish present rode to the future on rails. Monopolies and land baronage and all that. Still, you know how to tell a sweet story. Merry Christmas to everyone everywhere.

The true source of a nation’s wealth is its people. The looting of the 99% by the 1% is destroying that wealth.

I am a bit surprised that Lambert is undecided on the question of evolution vs. devolution.

For me it is dead simple. If you can no longer make things out of metal, you have devolved. Period. America is one of the world’s workshops, or it is nothing. The notion of a postindustrial economy here is a total shuck and a sham.

I speak as an engineer who does a lot of computation (mostly electromagnetism) but who also builds actual stuff– special orders in particular.

I admit this is not the norm, but I absolutely believe that we in America must make things or perish. The further we de-industrialize, the closer we approach third-class nationhood– we are already a second-class nation.

That’s certainly an important aspect I hoped to point out. It’s not the whole story though — the change in tenor for social relations between men strikes me as important. Granted, between men….

The demise of the Milwaukee Road is instructive. This short piece by Todd Jones covers the basics. http://www.trainweb.org/milwaukee/article.html

The most infamous descision, was made in February of that year. In that month, with copper prices at over a dollar a pound and 10 million pounds of it hanging over the Milwaukee’s right of way in the west, the decision was made to shut down the electrification. The directors of the Milwaukee had decided that instead of spending money to maintain and improve the mainline through Montana, they would consolidate, either through merger or trackage rights, trackage with Burlington Northern. The ten million dollars they expected to garner from sale of the overhead trolley was a bonus. This fact was confirmed by Lines West General Manager Quentin Torpin stating that the directors felt that a fixed system such as the electrifcation would be an impediment to their consolidation plans. Note that this decision was made even before the petition for inclusion was presented to the ICC in March of that year.

Of interest is the fact that both the Milwaukee and an independant group called the “Northwest Rail Improvement Commitee” compiled studies that showed for the cost of $39 million the system could be renewed with new locomotives, power supplies, and also close the “Gap” between Avery ID and Othello WA, improving efficiency. Full electrification would have allowed $21 million dollars worth of diesel locomotives to be transfered to the eastern lines of the road, reducing the net cost to $18 million dollars. GE even formally proposed financing the project, understanding the Milwaukee’s precarious position, but Chairman Quinn declined, stating that the company had “more immediate needs”. He did admit however that at current traffic levels and fuel prices, the “re” electrification would have paid for itself in 11 years. Instead the company would end up spending $39 million, yes, an equal amount, to completely dieselize Lines West while receiving only about $5 million dollars for the copper scrap as prices had dramatically fallen. What is most incredible is that the system was shut down during the Arab oil embargo, which had caused the costs of operations of diesel locomotives to skyrocket while the costs for electricity stayed relatively stable.

On June 15, 1974 when the last electric run was made, diesels cost twice as much to operate as the electrics. In a study done by Michael Sol it was found that if the electrification, as it existed in 1972, operating at maximum capacity, with no additional locomotives, the savings would have amounted to $32.6 million at the end of 1977 and $67.8 million by 1980 factoring in the increases in diesel fuel costs. Renewing the system would have paid for itself in 4 years.

Shameful. It reminds me of Los Angeles and the big red cars. Was this accompanied by executive looting, do you know?

I remember reading that the LA electric train system was one of many bought by front-companies set up by a three-way conspiracy of Firestone Tire and Rubber, General Motors, and Standard Oil of New Jersey. The goal of the conspiracy was to buy and destroy streetcar and trolley systems all over America in order to create a new market-vacuum to fill up with cars and buses.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_American_streetcar_scandal

i never got a train set BUT this xmas i got:

The Red Buddha : )

The Sound of Music/Mark Hartenbach (poems of jazz, blues, classical, country, folk, reggae, pop, etc: ))

&

6 Poets/John Thomas, Ann Menebroker, Ronald Koertge, Lyn Lifshin, Gerda Penfold WITH Drawings of each poet from Bukowski: )))

Words Become Magic Again

pick themselves up and dust off

the time that held them

words walk again

listening precisely to the sounds

that slide through the thin

sweet air

choice they say

harlot they laugh conjuring old-fashioned

colors deep as stained glass

the light streaming through

thief ancient one

the words are solemn

comrade they day poking each

other in the ribs like schoolboys

they walk through the double doors

of the old text to the wild king

who saw

the handwriting on the wall

i see the graffiti

of manhattan as wondrous art

illuminations

of the heart despised insisting

on love insisting

i see the long light of morning

now that

the words are here again

singular and savage

trying on their

new shoes

/maia penfold

Thank You ST from the whole of my heart.