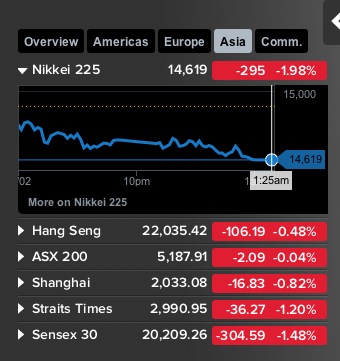

Emerging markets-related disruption continued overnight, as the Nikkei fell nearly 2%, pounded by the rise in the yen due to its status as a flight currency. Other Asian markets took a hit as well, with only Australia emerging relatively unscathed:

And the stress is unlikely to abate any time soon. Despite South Africa, Argentina, and Turkey having moved up interest rates to defend their currencies, theirs and other emerging markets still have their interest rates now looking too low in real terms. That puts the leaders of these countries in a no-win situation: let their currencies fall sharply, precipitating self-reinforcing capital flight, draining FX reserves, and stoking domestic inflation (worst, in food and fuel, which hit the poor and low income the hardest, increasing the risk of revolt) or raising interest rates, which is likely to trigger a slowdown, likely a full-blown recession. Here’s the underlying problem per Bloomberg:

Inflation-adjusted interest rates are still too low in developing nations for Citigroup Inc. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. to foresee an end to the worst emerging-market currency selloff in five years.

One-year borrowing costs in Turkey are 3.6 percent, less than half of the average in the three years before the 2008 global financial crisis, even after the central bank doubled its benchmark rate last week, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The real yield for Mexico is almost zero, while South Africa’s is 1.4 percent, compared with an average of 2 percent over the past decade.

Central bank rate increases in Turkey, India and South Africa last week failed to contain January’s 3 percent selloff in emerging-market currencies. Citigroup says yields aren’t high enough to attract the capital needed to finance current-account deficits in some of those nations….

One-year real yields in developing economies, based on the difference between interest-rate swaps and consumer-price inflation, are about 1 percent, according to Goldman Sachs. While rising, the rates are lower than the average of about 2 percent from 2004 to 2013, a model at the New York-based bank shows.

Even though the euro weakened this morning on the talk of a third bailout for Greece, and analysts now say it could fall further, from its current level of 1.35 to 1.30 versus the dollar, that still pales in comparison to the decline in emerging markets currencies such as the Turkish lira. And those moves are already having a detrimental impact in the weakest Eurozone countries. As the Financial Times’ Wolfgang Munchau informs us:

Start with the direct effect of the Turkish crisis on Greece and Cyprus. The magnitude is not that great on a global scale, but significant for the two countries. Their main industry – tourism – is competing head-on with Turkey. The Greeks and Cypriots have gone through incredible pains to improve their competitive position through wage and price cuts. The recovery in tourism is one of the few bright spots in their still depressed economies. The devaluation of the Turkish lira has put paid to all of this. Any holiday-maker headed for the eastern Mediterranean will find Turkey a lot cheaper. It is a game Greece and Cyprus cannot win.

And Munchau thinks the EM crisis could push the Eurozone, which is on the verge of debt deflation, over the brink:

For the eurozone as a whole, the main problem is not trade because it has a moderately large trade surplus. Instead, the problem is the impact on the price level. Eurostat, the EU’s statistics office, estimates that core inflation was 0.8 per cent in January….

At 0.8 per cent we are not far from outright deflation. A single large shock may be all that is needed. What is happening in Turkey and Argentina may constitute such a shock. And I have not even begun to talk about the possible consequences of shifting economic policy in China.

Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, promised last month to ease monetary policy if inflation ended lower than expected…But another smallish rate cut is not going to be enough. Monetary policy has many direct effects, for example on the stock market, but its effects on the price level takes time. A rate cut of 0.15 percentage points could never make the difference between deflation and price stability. The ECB will have to do a lot more heavy lifting to prevent deflation. I am not sure that we will see a sufficiently forceful response. And it has already left it rather late.

What is really troubling is that allowing inflation to drop and hold at its current level has already produced a type of deflation.

As the Belgian economist Paul de Grauwe recently noted, debt deflation can occur even when official inflation rates are positive. It happens when expectations of future inflation rates are lower than they were when the debt contracts were made.

This is clearly not an intuitive result. It means that when inflation expectations fall permanently, the value of existing debt rises – even if no new debt is incurred. We do not have to get to zero inflation to find ourselves in trouble.

Munchau isn’t the only commentator getting a tad nervous. SocGen issued a worried report over the weekend, as reported by Business Insider:

Following a week of extreme volatility in emerging markets, many wonder if we are now heading for a perfect storm, with China increasingly sucked in and Europe’s already low inflation falling further towards deflation. The current developments also mark a shift in markets’ focus on where the need for policy change is the greatest – away from Europe where bond spreads remain resilient. We remain unconvinced, however, that the reforms to date in Europe are enough to raise growth sufficiently and put public debt trajectories on a sustainable path.

This is also implicit in recent papers discussing how to deal with bailouts and debt restructuring in Europe (see for instance the Bundesbank). Notwithstanding the current signs of a genuine cyclical upturn in Europe, we fear that the lack of growth-enhancing reform will soon again show up in disappointing nominal growth.

Now some analysts, like Gavyn Davies, remain relatively sanguine, pointing out the the emerging markets crisis of the later 1990s produced only short-term disruption in advanced economies. That considerably underplays the dodged bullet of the LTCM bailout. But more important, as reader Scott has stressed, emerging markets were just over 30% of global GDP then versus roughly 50% now. It’s hard to imagine that if half of the world’s economies are in mild to severe distress that the rest of the world will get off scot free.

Thank you for this piece, Yves.

Now, if the top 85 wealthy people have as much as the bottom 3.5 billion people and the next couple dozen million have more than the bottom 5.5 billion, why should those billions of people at the bottom care about deflation? Isn’t deflation the rich man’s burden?

On the contrary: inflation benefits debtors by reducing the value of outstanding debt, while deflation benefits creditors, who see the value of their credit-based “assets” effectively increase.

There are people so poor that they can’t get any debt if they want.

For them, deflation is good. These poor people are not working but subsist on fixed, meager government welfare or survive on their own.

Deflation reduces employment.

These long term poor people are not working for someone else.

They may be on welfare, foragers, scavengers, hunters, etc.

For example, if they are on disability, deflation is good for them.

You think 3.5 billion people are on welfare? For the overwhelming majority of those people, paid work is the only way of obtaining money. Deflation will inevitably do more harm than good.

I didn’t say 3.5 billion people.

I said, there are people (as in, some people and not all) for whom deflation is good.

That’s different from saying deflation (or inflation) is good for all.

See below, my comment earlier today.

Unless the debtors default.

true inflation also assumes that wages are rising as well.

if wages are not rising, then inflation can’t survive for long.

Well, as you might have seen in the on-going inflation hysteria of the last years (decades?), it is inflation that is the rich man’s specter since higher prices mean that they are less “rich” (unless it is asset inflation instead of price inflation).

And as the Münchau piece points out, since debt is typically in nominal terms, deflation is also equivalent to increasing debt, of which the wealthiest are much less likely to have any than the poor.

But more importantly, deflation is handed through in the form of wage cuts or lay offs.

BigRed, you’re right about the different inflations – asset, price, etc.

As such, there are no general statements to be made.

It could be that a rich guy with a factory who can benefit from asset and price inflation on top of wage deflation as he pays his workers less.

Or it could be a rich guy running a brainwashing outfit who worries mainly about rising wage inflation and is constantly freaking out over that specter.

Then there is that rich hedgie who makes money in all market conditions.

I am sick to my teeth of economists talking about exports and tourism as if it were the only viable means of exchange.

Ever since countries such as Ireland had joined the EEC in the early 70s they have seen a decline of basic secondary industry servicing basic domestic demand.

This can easily be seen in their energy balance where oil used in Industry peaked in the early 70s and the surplus transferred to cars and airplanes which serve a capital dumping function in the EU and its wider hinterland.

The data is starring us in the face and yet we cannot see it.

We must ask if car growth in the UK is causing this present strain on the various turkeys of Europe.

Now that cars are reaching saturation on the UK mainland Ireland is beginning to absorb these almost useless (at $100 a barrel) capital dumping products as banks wish to search for meaningless yield.

Growth is dead , long live the cars.

Total new Irish passenger car sales

Jan 2014 : 22,927

Jan 2013 : 17,242

A growth rate of 33%

Y2013 Total car sales : 74,303

Y2014 Total car sales :100,000~ ?????

We can clearly see what is happening in the Irish fiefdom.

The consumption of basic fiat centric goods is being sacrificed on the alter of credit centric goods.

Light commercial vehicles also up

Jan 2013 : 2,845

Jan 2014 : 1,998

42% rise

total van sales Y2013 : 11,076.

As you can see January defines the entire years car sales as it is normally the biggest sales month by a wide margin.

http://www.beepbeep.ie/stats/?sYear%5B%5D=2014&sYear%5B%5D=2013&sRegType=1&sMonth%5B%5D=1&sMonth%5B%5D=12&x=49&y=14

This is a long term pattern since EEC entry in the early 1970s when oil use in Industry peaked and began to contract.

The domestic economy of basic secondary goods production must contract so as to service the cars as you get a hollowing out of real domestic exchange.

However this “growth” in the UK and now it seems Ireland is having profound effects.

The central problem of Europe remains.

It produces products which we cannot afford to buy.

Indeed we have seen this since the early 1970 at the very least.

How long does it take for people to see that the production , distribution and consumption system in Europe (i.e the entire Industrial system) .is a failure.

Long distance trade (or holidays) is not a winning formula.

The externalities (fully imposed on people via tax rises ,wage deflation and internal goods price inflation) are beyond all of what we have known in the past.

Eventually that Airbus bound for Bodrum will simply not take off.

The dark euro project will create more and more Spanish failures until it cannot.

Turkey and Morocco are now just more Spains.

Where too tomorrow ?

“”Citigroup says yields aren’t high enough to attract the capital needed to finance current-account deficits in some of those nations….””

This would probably be a good one line summation of Michael Hudson’s book ‘Trade, Development and Foreign Debt’ 2009.

Basically countries need to employ labor to supply domestic consumption as the first order of business. Interest rate swaps and foreign exchange swaps aren’t the right tools to build an economy.

But the next thing you know the labor will want a raise, then benefits, then shorter hours and before you know it we’ll be back to the Long Dark Totalitarian Night otherwise known as the Eisenhower Administration.

Most. Hilarious. Comment. Ever!!

Yep. You wonder how our economy survived back then, if you listen to mainstream economists pontificating about optimal conditions for economic growth.

I don’t think this piece offers a satisfactory explanation for what is going on. Yes, selected markets tanked over night. But the reason they tanked is probably generalized fear that they have stopped going up and thus provide no reason for nervous money to continue in them. Trends continue until they end. That is all they do. Can monetary authorities do anything to restore confidence? Does it really matter if interest rates rise by one percent? I doubt it, but we’ll see.

As our financial system becomes more complex and interconnected it also becomes more prone to unforeseeable, cascading catastrophic events. The more complexity we create, the more likely we are to experience “butterfly effect” events and the less likely we are to be able to predict them. At this late stage in the game, I think things have gotten so complex and inter-twingled that it isn’t possible to predict what will set the whole thing tumbling, but it gets ever more likely that something will.

I agree. And I believe the derivatives butterfly is likely emerging from its cocoon in the hidden, unregulated jungle of currency and interest rate swaps.

The relationship between complexity and stability is not yet quite clear, not even whether there is any general law there.

Some systems may be stable because they are complex, having lots of redundancies (by virtue of their complexity) that cover for failures in some parts.

Some other systems are very simple and very unstable, depending critically on a single external forcing (witness the behavior of simple nonlinear difference eqs.).

Finally, one can reasonably argue that the international financial systems is becoming more and more simple in the way that matters the most, because more and more wealth is concentrated on less and less players.

Likewise, inside nations income inequality is reducing the complexity of the productivity fabric as more and more wealth is concentrated on less people so less productive talent is harvested by means of diversification.

Forgive the groundless paranoia, but one of the results of the current currency markets will be to make assets in the developing countries a lot cheaper for the industrial powers. And it would teach those uppity small country socialists a thing or two. And it make supranational currencies look like an attractive alternative.

Since the fall in value is happening on the (European) FX markets, and no one who can tie their own shoes believes in the Free Market story, are the traders reacting to conditions or according to an agenda? And how would we know?

So, if this were a bear raid, or a policy with a political/economic agenda, is there any way to tie the actions to the actors? Not my field, but it looks like a duck.

I think it’s possible to be both traders reacting to conditions AND according to an agenda.

One can do that by rendering an agenda into conditions, which traders will react to in a pre-determined way.

For example, one could, on purpose, pump up the emerging markets to levels that they naturally will come crashing down.

The EM story is simple. The EM countries grow not only based on their own internal demand, but from demand from the developed markets. The Developed Markets , both the US and Europe, have cut the standard of living of their working class and middle class by about 6%. It is now clear that the DMs will not recover this demand in the foreseeable future. This drains demand from the EMs disproportionately, since their neo-mercantilist game will be harder to play in the future. We are far enough into the DM ‘recovery’ for it to be clear that there will be far more difficult to play off DM demand in the near future.

This whole movement is forcing a economic revaluation amoung the EM economies, driven by a fall in potential global demand. No return to 1996 or 2004.

Can anyone point to a crisis in financial history in which everyone was saying beforehand, ‘abandon ship, we’re doomed’? All the ones I know about were full of dross balanced by dross like this article – no criticism of Yves here, just the ahistoric nature of economists’ claims generally. We do little more than sit round casting runes.

Typical in economic debate are terms like ‘inflation’ and ‘tax’ being given certain meaning they do no possess. I know what I will pay as tax tomorrow when I do my return. Yet it is equally obvious to me that I pay tax other than to the tax man. University fees are a classic (who care if you pay them directly to academic idlers or through government) and health and sickness care. Somerset (3%) has been under flood water for 3 months. I suspect this is because our water systems have been privatised and much previously routine river dredging and other water channel management just doesn’t get done because it is a cost on private P & L. Now we will have to raises taxes not previously paid for years through ‘privatisation’ to (literally) bail out Somerset.

We are walking amongst the shards of pathetic ideological battles between communism-capitalism, nationalisation-privatisation and the rest – all marked by ideological rhetoric and lack of real evidence. I rather like the concept of choice – but do I really get any? Do I give a toss if I pay my grandson’s tuition fees to his university or to the government, A resounding no. I care they are at least £7K a year too much and diluted to school levels.

Once we get to elaborate stuff like ’emerging market contagion’ how are we likely to be able to cope at all when we can’t even get simple terms like tax right, or make ‘private sector free market’ (mythical) assumptions that make such phrases ideological goods. I can only guess what we would need to define – no doubt QE and other slippery slope measures produced hot money that chased into emerging economies, hoping to be in and out in an insider known period, taking high return, doing the FX before withdrawal leaves suckers holding the inflation and asset price collapse babies. I have further suspicions (Dork has posted some), but who could know at the distance of study. I’d need authority to investigate, get people on the inside and track actual transactions, not cope with accounts designed to hide everything.

I suspect emerging markets have been subject to a ramping scam in which hot money piles in solely to put prices up and flip out leaving a demand slump. This is a tax on wages and ordinary people. Sooner or later people will come looking for these fraudulent tax men. Some of us think the last ten years has seen no real growth at all and huge numbers of claimed assets are worthless, such a mall and town centre properties, perhaps 50% of shares and bonds and 90% of current dot.con. What appals us is the lack of any real plan B to redistribute assets and work and all the feeble arguments that assume anyone with any current riches earned them.

Afghanistan had a plan for local industry making goods for local demand, agricultural modernisation – and more in 1930. We put paid to that. These were times we colluded with Argentine oligarchs to suppress any working class there by swapping over-priced British manufactures to their beef. A big part of all this financial instability stuff concerns how ‘hot money’ has taken the role of such invidious foreign policy.

The real questions concern how we stop the drift headlong into being the serfs of financial despots. The system needs to collapse. We should be sequestering the rich and taking control of the means (and irrationality, cruelty and pain) of production out of their hands. The question of who goes bankrupt when the music stops is an old one, as is he history of those who play this game whilst hoarding liquid assets to buy cheap when no one else can raise money. We aren’t looking deeply enough into any of these half-arguments.

Good points. Academic idlers, indeed. Add political parasitic class. The present era we reside in, with no parallel in all history of untold wealth, is producing a cleft that will have to be addressed, one way or another. We already find ourselves, in many countries, in a wash, rinse, repeat feudal system. This time it’s overwhemingly larger, clevelry and complex constructed, and the lords have at their disposal the taxpayer funded forces to deal with insurrections. To change the status quo, save for a systemic collapse, will take fortitude and courage amongst those who recognize the diabolical bondage with which the era of unfettered, unchecked corrupt finance has shackled the many. To date many are enthralled and content with watching Benefit Street. But one day that show will end. Governments are essentially privitised entities engaged in a wholesale liquidation of the public purse for private interests. A topsy turvey world. But the West itself is bankrupt with no new rabbits to pull out of the financial magic hat. The post 911 and 2008 phony money pumping excercises have run their course. All that is left is Boris’ and David’s groveling to welcome the globe’s wealthy into London to pump up property prices and trade at upscale stores. That’s it. They have no other plan, because there isn’t any. Game over. If there is a collapse may it also bring an end to the devastation that globalisation has wrought.

Ring around the money

A pocket full of none…y

Derivatives, derivatives

We all fall down

Or maybe better…

Ring around the debts

A pocket full of bets

Derivatives, derivatives

We all fall down

Either suits as a modern plague song psyhist. Hard not to agree with Steve. Yves and Lambert make the BBC coverage look like undergraduates scared to look further than a few set textbooks. Some of the academics like Keen, Hudson, Kelten and Black at least open ground I think can be discussed, but most of the rambling looks like reading poison oracles to me. Even South Park got to that.

Given the long-term record of loans to emerging markets looks like banks growing wealthy making bad loans (seemingly impossible) and what we know of banks’ insider knowledge use and front running, we seem to lack a lot of knowledge on just what a relevant network for financial analysis is. In systems we would look for soft spots, but finance seeks to disguise them. If you find one as a financial speculator you presumably seek investments that will earn well if you can pull the lever that collapses the house of cards. This can’t be done in full transparency and we discourage transparency to ‘aid’ liquidity. Without detailed money trails we are left trying to guess whether today’s system is like ones in the past and likely to behave in the same way. The obvious similar feature of recent past and present systems is the rich are taking bigger and bigger shares through money moving schemes otherwise disconnected from production and consumption. The high rates of return once seen on manufactures were maintained by very dirty deals and finance is now very ugly. I wonder what an analysis of emerging market finance would look like conducted by (mythical) untouchable cops instead of the functionaries of economics.

allcoppedout said: I wonder what an analysis of emerging market finance would look like conducted by (mythical) untouchable cops instead of the functionaries of economics.

I posit that any serious analysis of emerging market finance would support the description in The Shock Doctrine book wherein countries are “evolved” to support ongoing accumulation of private ownership of everything and associated inheritance “laws” by a small elite who are then “managed” to insure their ongoing fealty to global “capitalism” and its inherent vampire plutocrat masters.

I believe the worldGDP of EM it’s actually closer to 40-45% (based on what I saw), but the point stands that it’s much higher than it was.

That said, I’ll still make a different point – US economy is as close to an autarky in trade terms as you get in this world short of North Korea and a few embargoed countries, so while the world catches cold when US sneezes, it doesn’t entirely work that way that when the world sneezes (unless the US banks catch cold, which is quite a possibility, although it would have to come from EU/China rather than normal EM, so a few steps removed). So I expect Fed not to be too much bothered – just yet. The PMI numbers were bad yesterday, but my surprise was more that the expectation were so high – did the forecaster look out of the window in Dec/early Jan? Did they read the comments from various industries way before (as in deliveries delayed due to weather, general problems for just about anyone with workforce etc. etc.)? I fully expect that the Dec payrolls will be lower on Friday, but whether it matters or not I believe we won’t know until March or so (that said, I still think there’s way too much part-time jobs for the economy to be healthy).

The big part of the EM story for US is profits of the multinationals (that are driven by EM to a nontrivial extent). In theory, again that could make no difference as a vast majority of that is not repatriated to the US, but it would of course affect stock markets. So if you’re looking at an economy via stock market glasses, it is turning bad. Impact to SMEs in the US is I’d say still in the stars.

The same could go to some extent for EU, except for its internal tensions which if anyting will get excerbated by the EM stuff (lots of EU banks does have some exposure to EMs.. more than US I believe). I wonder whether EM will be the catalyst that sparks the last (maybe? there was so many “lasts” here..) phase for EU catasthropy (as EMs aren’t something EU can fudge…)