By Matt Stoller, who writes for Salon and has contributed to Politico, Alternet, Salon, The Nation and Reuters. You can reach him at stoller (at) gmail.com or follow him on Twitter at @matthewstoller. Originally published at Observations on Credit and Surveillance

The credit card industry gets short shrift when it comes to history. It’s really not fair, and it’s a problem because it means a good portion of the lifestyle of ordinary Americans is not well-understood by historians. But the reason is that there just aren’t a lot of colorful personalities around credit cards; it wasn’t an industry invented in a garage by a group of plucky inventors. Credit cards were from the very beginning a product developed by faceless bureaucrats in extremely large oligopolistic industries fighting one another over who would control access to the American consumer. It’s an industry best studied through the lens of class, and not in the current style of narratives focusing on individual heroes.

Most of the early hearings on credit cards involve oil companies and antitrust. This is because oil companies, like airlines, large retailers, and restaurants and hotel associations were attempting to corner the market in consumer credit. While today credit cards are a bank product, banks didn’t take a majority of the business until the 1980s. It was primarily oil companies that got the credit card business going, in the 1930s. Standard Oil of California, for instance, did a mass mailing of 250,000 cards in 1939, using early ‘big data’ (well not big data really but using early direct marketing) techniques and experiencing identity theft and fraud. They did this not to make money on credit, which wasn’t seen as a profit center, but to sell more oil at higher prices. Early credit card operations were about getting Americans comfortable with driving cross-country, and being able to buy gas conveniently everywhere.

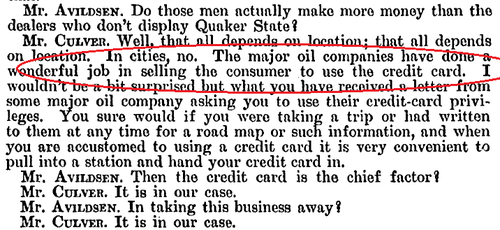

In October of 1939, the Temporary National Economic Committee in the Senate held a hearing titled “Investigation of Concentration of Economic Power”, with a focus on the petroleum industry (link here, be warned it’s a big file). Credit cards were prominently featured, because the major companies in the oil industry were using the large customer bases they had acquired as a bludgeon to control independent gas station owners. The majors were colluding, and using market power rather than direct ownership in gas stations to eliminate those who made rival products, like Quaker State and Pennzoil. Here’s a rep from Quaker State complaining to the Senate.

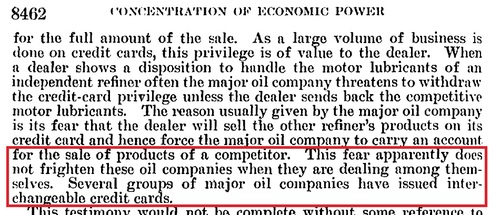

So it was the oil industry that got Americans used to credit cards. As for the collusion? Well that was clear as well. Here’s Charles Suhr, from Pennzoil, explaining how the oil majors controlled the industry through credit cards and fake independent leases of gas stations.

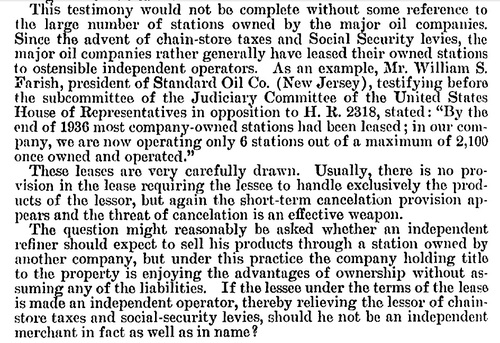

And then Suhr went on to show how the government was being deceived by claims from the oil guys barons that they didn’t own the gas stations at which Americans shopped.

Today, the oil industry’s main problem is finding enough oil to refine and sell to plentiful car-dependent customers at high prices. In the 1930s, the oil industry’s main problem was finding enough car-dependent customers to which they could sell plentiful cheap oil. As scholar Tim Mitchell pointed out in his remarkable book Carbon Democracy, the problem for the industry was always too much oil, not Daniel Yergen’s absurd argument in “The Prize” about how oil was eagerly sought after. No, oil was always a question of structuring a market to generate profits when the natural contours of that market wouldn’t necessarily lead to much more than a cheap commodified standard good. Credit cards, as a mechanism to induce Americans to drive more while also extending the control of oil barons over the gas station market, were one answer.

Americans will fall for just about anything. They’re arrogant, easily flattered, and really not very bright. Nobody ever went broke overestimating the cupidity of the American people.

Oil Companies: “Suckers!”

I’m not up this early normally on a Saturday morning. Clearly I have missed something, because I love credit cards. They are simple, reliable, helpful for budgeting/tracking, and remarkably theft-resistant.

The problem with big oil is dismantling our passenger rail system and secrecy surrounding environmental devastation.

Okay, who do you work for? Credit cards are in almost no way theft resistant, though they could be if credit card companies weren’t so busy looting. They’re not helpful for budgeting or tracking unless you use only one. They charge ridiculous fees to merchants of 2-4%, and rape citizens with outrageous interest rates and fees who have the misfortune to not earn enough to survive without rolling over balances. Credit cards are one of the ways capitalists have enslaved the people: don’t pay them a living wage, hook them on credit cards, make bankruptcy difficult and exorbitantly expensive and you can loot them for life. Wake up later next Saturday.

However when it comes to theft credit cards are far safer for the consumer than cash. The limit of the amount to loose if you carry cash is that amount, with credit cards (not debit cards) its $50 by law, and effectively $0 because most card issuers don’t bother. The costs of fraud are born by merchants and the banks. It is easy to avoid most consumer credit card direct fees, treat the card as a charge card and pay it off in full each month.

Folks that talk about the merchant charges have never provided what the costs of handling cash are. Consider that a merchant needs at a minimum cash handling procedures including having money counted by two people, either having it picked up by an armored car, or taking the cash to the bank, any bank charges for counting coins etc. For checks you have the handling charges and bank charges.

So its not clear that credit cards really cost merchants more than other means of payment.

I see two benefits to using credit cards: accounting (which DOES work if you spend on only one personal and one business card) and chargebacks. Being able to dispute a charge if a merchants sends you something damaged or other than what you ordered and refuses to make the situation right is valuable.

The big problem with credit cards is the lack of annual fees. Until the mid 1980s (I believe it was the then Maryland National Bank that screwed it up) banks had a tidy agreement on pricing: annual fees, max interest charge of 19.8% (remember, underlying interest rates were higher then, and some banks charged a little less in interest for high credit quality customers). This meant banks made money on every type of customer: the ones who only rarely used the card, the regular user who always paid in full, the customer who once in a while ran a balance (say sloppy about payment dates or ran balances or big purchases and paid them off in a couple of months) and debt junkies. This incentive structure also made banks NOT want debt junkies.

Eliminating annual fees meant on those cards, the banks made money only on the customer side from fees (which increasingly became “gotcha” fees) and interest, which meant the banks had an incentive to push credit onto people they could bleed dry.

Oh, and it was MBNA (credit card unit of Maryland National Bank) that was the moving force behind getting the bankruptcy laws changed in 2005, which favored them. Made it harder for people to get their debts wiped out in bankruptcy; more have to go through Chapter 13, which forces people to eat rice and beans for 60 months to repay creditors as much as they possibly can (I’m not exaggerating).

MBNA figured the “reforms” would enable them to extract $100 more a month from bankrupt customers, which was worth $85 million a year to them.

Accounting benefits and chargebacks aren’t necessarily exclusive to credit cards, are they? I find it hard to identify any benefit exclusive to credit cards relative to other cash alternatives, other than cash-free purchase without penalty for up to 30 days. Debit cards offer accounting benefits and, in Germany, chargebacks. Checking offers the fewest benefits as far as I can tell. As with the other alternatives, checks offer cash-free purchase/payment. And as a hardcopy personal note they facilitated trade before the internet. But today they are obsolete from the consumer point of view. They continue to be popular I imagine solely as a hidden tax on the poor. I have a personal theory that banks offer checking as a way to steer consumers to credit cards, which offer greater returns, at least in the USA.

Thanks for following this story, and to Stoller for reminding us of the role of oil companies in the history of credit card use in the USA. I seem to recall that the first credit cards that I was aware of were the mobil and esso cards used by my parents, I imagine in the 60s or 70s.

In America, you don’t get accounting with debit cards. My business credit card sorts the spending into merchant categories. The reporting on debit cards is way less good.

And debit cards are treated just like cash here. No chargebacks, and if someone gets your card, they can drain your account, while with credit cards, the most you can lose is $50. I’ve never lost a dime the times I’ve had my wallet stolen and the cards used.

Well said. And I would add one more – credit cards are the only widely accessible form of credit that doesn’t require collateral. That means a small business owner or individual living paycheck to paycheck can float expenses. Doing that with debit cards is impossible (well, unless you’re going to pay overdraft fees), and doing that with checks is illegal (kiting).

Personal checks still provide proof of payment compared to cash.

I don’t understand why US debit cards are limited and so vulnerable. Here in Germany, debit cards are virtually unchallenged among alternatives to cash. They offer accounting benefits to the extent that you get a statement at the end of each month, that you can balance against purchase receipts. And there is a daily limit on how much it can be used, generally the default is €1000. We lost €1000 once after a wallet was stolen – it didn’t help that my partner post-it-ed the PIN in the wallet. You can set the limit lower or higher. Debt junkies must be suffering in Germany too, but I don’t know any, nor do I know a German who has more than one credit card.

And thanks for the tip about cancelled checks as proof of purchase. I imagine retailers are able to sync form of payment to the receipt print function – do not print if the customer pays by check. Those rolls of paper tend to be outrageously expensive.

Are US debit cards limited because banks want to protect the advantages they enjoy as a result of checking and credit cards?

I find this pretty comical. What you are describing can be said of alcohol or sex or baseball or movies. Of course they’re tools of addiction and social control.

But to deprive ourselves of an easier life out of some moral hermit separation from the world as it actually exists is not a type of martyrdom that interests me. Credit cards make my life easier. I’m not an evangelist – if they don’t make your life easier, don’t use them! I hate coffee; some people love it.

By the way, they also make life easier for merchants. I always ask if a merchant gives a discount for paying without plastic. None do these days. Have you ever had to deal with fraudulent checks, for example? Now that’s a huge hassle for an organization.

‘A question of structuring a market to generate profits when the natural contours of that market wouldn’t necessarily lead to much more than a cheap commodified standard good.’

Gaining an exclusive edge with a commodity product is an endlessly recurring problem. Thus we get razors with proprietary blades; first-mover advantage in computer and phone operating systems; telcos who subsidize phones to lock in wireless service contracts; and so forth.

Bankamericard (the predecessor of VISA) became omnipresent in the 1960s. The working adults of the time — the children of a preceding generation of cash-only, savings-oriented parents — thought credit cards were the coolest thing since rock ‘n roll. Turns out they’re easier to get hooked on than drugs, and can damage your life for a lot longer.

The first unsolicited credit-card offer I ever received was from Exxon. Other huge industries, with a desire to get folks spending beyond their means and extracting even more consumers’ wealth from excessive interest charges, eventually got into this same game. Look at GE and GM, for example.

Students at expensive colleges are swamped with easy credit card deals the moment they set foot on campus. It’s tragic to see how many folks are sucked into a brief period of over-spending, followed by years of crushing debt payments.

As an Norwegian the use of credit cards in USA have always been a bemusing puzzle.

Our telco system sucks, so few people would trust their phone even if it could be made to work well. Cash is inconvenient, suspicious in many cases, and susceptible to theft in the drug war-induced environment of petty crime in the US. Checks are way more inconvenient for retail transactions than plastic.

Wikipedia has a good discussion of the history of credit cards, starting with Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backwards. The banks promotion of CC in the 1950s was to my mind far more important than Big Oil. But there were limits. Kids could get them.

Then sometime in the 70s or 80s they began to send highschoolers CC offers. And so it goes, free money.

And today, the two US companies mentioned in the Senate testimony, Pennzoil and Quaker State, are both owned by Royal Dutch Shell, one of the five “Supermajor” international oil giants, and franchiser of Shell branded gas stations.

For more on “CARBON DEMOCRACY”, here is a link interviewing the author.

Timothy Mitchell on Infra-Theory, the State Effect, and the Technopolitics of Oil

http://www.theory-talks.org/2013/10/theory-talk-59.html

I’m old enough to remember that when I graduated from high school (late 1970s), getting a credit card was a Big Deal. As I recall, it was very, very difficult to obtain one. Besides the gas stations’ cards, American Express (which was virtually impossible to get because AMEX demanded full payment at the end of each month), or Diners Club were the only cards that I can recall. And only “rich people” had one. My dad, who was a local banker, impressed upon me that you needed not only a good job, and good credit history, but also sterling character references. I remember thinking it would take me forever to get my own credit card because I’d have to build up my credit history. Thanks to the deregulation in the 1980s, those days are long gone. Seems to me that easy access to unsecured credit back in those days inured our fellow American citizens to the entitlement of so-called easy credit generally–including mortgages, HELOCs, and the like. The financial landscape these days (reverse mortgages–REALLY??) is completely unrecognizable and gee whiz, I’m only in my 50’s. Folks, we done got took to the cleaners.

My first credit card was mailed to me, unsolicited, when I was first year university, that would be 1967. Everyone in my dorm got one, do you suppose the university was selling our names and addresses? Well, yeah. The gas credit cards were very enticing, meant that you could go on vacation without having to have tons of cash on your person to pay for gas — just hotel/motel and food. Helped a lot, back in 1965. The oilco’s got brand loyalty, we got, well, we got a piece of plastic that couldn’t be stolen, at least not easily, and we didn’t have to carry cash. Before trans-state banks, let alone debit cards, check-cashing was an adventure, to say the least, cash was the only way. And they would hold the bill to the end of the month – cool!

Our local major stores had ‘revolving’ charge cards.

I, too remember both the introduction of the Visa card and the prevalence of oil company cards. IIRC, I got one or two oil company cards with super-low limits (like $100 a month) and paid them off religiously every month until I had built up enough credit to get a Visa card. Eventually this let me get enough credit established to buy a new car. At one time I had oil company cards for Exxon, Mobil, Chevron, and Texaco. Made it handy on all my long distance and cross-country excursions. Now I’m down to one Citibank card strictly for business, one for personal (both with frequent flier miles) and a Cap One card as a backup.

The year credit cards went bonkers was 1978 when SCOTUS ruled Marquette Nat. Bank of Minneapolis v. First of Omaha Service Corp. SCOTUS said state usury laws could not be used on out-of-state credit cards. A key point: “The case has been called one of the most important of the late 20th century, since it freed nationally chartered banks to offer credit cards to anyone in the U.S. they deemed qualified, and more specifically because it allowed them to export interest rates to states with stricter regulations, opening up a race to the bottom between U.S. states in an effort to attract lending institutions to set up shop in their states.” The dawn of the 25-30% credit card.

The decision? “On December 18, 1978, the high court, fully agreeing with Marshall’s analysis, ruled unanimously in First National Bank’s favor. The decision maintained that the 115-year-old National Bank Act takes precedence over usury statutes in individual states. Justice William Brennan wrote that the 1863 law permitted a national bank to charge interest at the rate allowed by the regulations of the state in which the lending institution is located.” Justice Brennan wrote the opinion.

The supporters of SCOTUS ruling say it eliminated “archaic and largely ineffective usury restrictions, Marquette increased efficiency and competition in the credit card industry, made the market more responsive to consumer demand, and provided large benefits to consumers.” The critics always expected Congress to reconcile the issue as the effect was to gut every state law on usury, he says. The 1863 Congress, Geoghegan complains, couldn’t have imagined credit cards when it passed the National Banking Act. He conceded that Brennan’s opinion is technically right, but speculates that the justice thought Congress would step into the gap afterwards and enact a national credit-card rate cap, although that was politically unlikely at the time.

Precursor to 2008.

Interstate races to the bottom seems to be a repeating pattern in USA. Another such race turned Delaware into the incorporation center by virtue of having the most lenient laws.

And i wonder if something similar is being the hidden agenda of EU, and ultimately international trade agreements.

Several points:

1. Even Yergin points out that *never* in history has oil been without price management. Whether it was Rockefeller’s monopoly, or the OPEC oligopoly (or the Texas Railroad commission, the Oklahoma Corporation commission, or Harold Icke’s office in FDR’s white house), the free market *always* took a back seat to price management. Prices were otherwise far too volatile to have oil survive as a business. Greg Palast even suggests the Iraq war was cooked up to keep the oil in Iraq (second largest proven reserves to the Saudis) in the ground.

2. I’m not sure credit cards are as much to blame for the necessity of driving as “white flight” to the suburbs, and American’s suburbanized “planning.” Before the 1950s, Americans built cities on the grid plan, with several destinations within a walk of each other (“mixed use”) and the streets were pedestrian-friendly…set back, wider sidewalks, vertical curbs, small radii at corners. After sprawl became the rule, destinations were far apart (“single use”), and streets were auto-friendly. Large-radius corners pull back the corners so pedestrians have even farther to walk, while autos can take the turns at high speeds. See Complete Streets for the description of the alternative.

What the adoption of sprawl means is that the natural gathering places of political movements (e.g. the “town square”) no longer exists. The degradation of the public realm is literally cast in concrete. Among other things, people can’t walk places, culture declines, isolation increases, and auto-dependence increases. Public transit has a terrible time attracting ridership. After all, who can manage to walk to the stops?

This has been a long time coming, and it will take a long time to unravel all the forces that brought us to this present situation. As H.G. Wells says “Civilization is a race between education and catastrophe.”