Yves here. While oligarchy has now become safe to use in polite company in the US, that’s in part because it’s behind the state of play. As NC regular Hugh likes to remind us, kleptocracy is in many ways a more apt description for our devolving economic system.

If kleptocracy is a disease, Tunisia is in Stage 4. Its ruling family that controlled an impressive swathe of the economy. But what is sobering about the Tunisian case study is that an overthrow of the government has done little to reverse the concentration of wealth and power. Is that because Tunisia was so far gone, or is this native to kleptocracy, that once it becomes established, it is difficult to extirpate? However, in Tunisia, regulation was the vehicle for creating near-monopoly conditions, while in the US, deregulation and weak anti-trust enforcement have facilitated increasing concentrations of wealth and power.

By Bob Rijkers, an economist in the Trade and International Integration Unit of the Development Economics Research Group, World Bank: Caroline Freund, former chief economist, Middle East and North Africa, World Bank: and Antonio Nucifora, lead economist for Tunisia, World Bank. Adapted from a post on the World Bank’s future development website

From the powerful oil barons in the USA in the 1920s to today’s oligarchs in Russia and Ukraine, entrenched interests have been a major concern over time and around the globe. North Africa is no exception. The fortunes accumulated by the family and friends of President Zine Al-Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak of Egypt were so obscene that they helped trigger the Arab Spring revolutions, with protestors demanding an end to corruption by the elite.

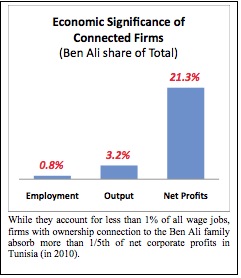

In a new study, we find that the scale of state capture in Tunisia under Ben Ali’s was extraordinary—by the end of 2010 some 220 firms connected to Ben Ali and his extended family were capturing an astounding 21% of all private sector profits annually in Tunisia (or $233 million , corresponding to over 0.5 percent of GDP).*

Tunisia’s post-2011 opening gave us a unique opportunity to explore data that was previously inaccessible to the public. In collaboration with Tunisia’s National Statistical Office, we compiled a unique data set: We merged data on the investment regulations with balance sheet and firm-level census data from Tunisia for 1994–2010 in which we identified 220 firms connected to Ben Ali’s extended family (as identified by the Commission charged with confiscating the assets which belonged to Ben Ali and his extended family).

Tunisia’s post-2011 opening gave us a unique opportunity to explore data that was previously inaccessible to the public. In collaboration with Tunisia’s National Statistical Office, we compiled a unique data set: We merged data on the investment regulations with balance sheet and firm-level census data from Tunisia for 1994–2010 in which we identified 220 firms connected to Ben Ali’s extended family (as identified by the Commission charged with confiscating the assets which belonged to Ben Ali and his extended family).

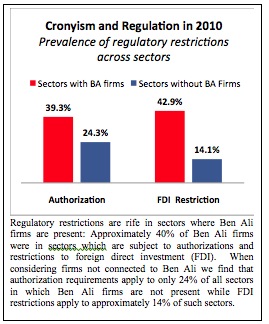

These connected firms grossly outperform their competitors in terms of employment, output, market share, growth, and indeed profits. How did they do this? The sectors in which these firms are active (such as telecoms, air and maritime transport, commerce and distribution, financial sector, real estate, and hotels and restaurants) are disproportionately subject to restrictions on entry and foreign investment.  The performance of firms connected to Ben Ali’s family is significantly larger when they operate in these highly regulated sectors. Put simply, constrained competition allowed more rents to accrue to Ben Ali firms. It didn’t stop there. If regulations did not protect a lucrative sector, Ben Ali would use executive powers to change the legislation in his favor. Specifically, the introduction of new restrictions to foreign investment and authorization requirements is correlated with the presence and entry of firms connected to Ben Ali’s family. Over a 16-year period Ben Ali signed 25 decrees introducing new authorization requirements in 45 different sectors and new FDI restrictions in 28 sectors that served to carve out and protect clan interests from competition—providing additional opportunities to extract extraordinary profits.

The performance of firms connected to Ben Ali’s family is significantly larger when they operate in these highly regulated sectors. Put simply, constrained competition allowed more rents to accrue to Ben Ali firms. It didn’t stop there. If regulations did not protect a lucrative sector, Ben Ali would use executive powers to change the legislation in his favor. Specifically, the introduction of new restrictions to foreign investment and authorization requirements is correlated with the presence and entry of firms connected to Ben Ali’s family. Over a 16-year period Ben Ali signed 25 decrees introducing new authorization requirements in 45 different sectors and new FDI restrictions in 28 sectors that served to carve out and protect clan interests from competition—providing additional opportunities to extract extraordinary profits.

The evidence we find is consistent with a large body of literature showing that countries with more extensive business entry regulations tend to grow more slowly and have higher levels of corruption. Our results demonstrate that, in addition to disrupting firm growth and creating opportunities for bribery, cumbersome entry regulations are also likely to be systematically abused by the state when institutions are weak. The consequences of this use of regulations to extract rents (i.e. to appropriate wealth) is much worse than just the cost of the petty corruption. Consumers pay monopoly prices. Firms have no incentive to improve product quality. And the productivity gains and innovation that would come from new firms is halted. In other words, it undermines the competitiveness of the economy, hampering investment and the creation of jobs.

Three years after the revolution, the economic system that existed under Ben Ali has not been changed significantly—and the demands of Tunisians for access to economic opportunity are far from being realized. While efforts have been made to revise or reform some of these regulations, there is a possibility that Tunisia will have completed its political transition without reforming what was one of the principal facilitators of the corruption and cronyism that sent so many Tunisians to the streets three years ago.

Tunisia has taken a first and very important step: offering wider access to data and information to improve accountability. Now it is time for the second step, removing the regulatory barriers that protected the few at the expense of many.

______________

(*) All in the Family, State Capture in Tunisia, is the World Bank Working Paper number WPS 6810 and is available for download at the following link:

http://econ.worldbank.org/external/default/main?menuPK=577939&pagePK=64165265&piPK=64165423&theSitePK=469382

Is it just me or does this read like it’s going to be used to justify blanket deregulation?

Perhaps, although I think the take-away here is that regulations, just like anything else, can be used for good of for ill. Regs can be used to protect the environment, or to prevent new entrants from challenging established firms, or to keep same-sex couples from marrying. The type of rhetoric that claims “regulation is bad!” or “regulation is good!” is exceedingly harmful to public discourse, for just this reason. It serves to distract from the actual realities of a given situation by recourse to philosophical, universalizing statements that, while emotionally appealing, do more to conceal than to reveal.

As Ani Difranco puts it, “Every tool is a weapon, if hold it right.”

The authors make this point Dip – though not as well as you. The paper reduced me to rant (below). We could get beyond the paradox of regulation-deregulation by examining the quality and consequences of both. I don’t see the ‘technology’ as neutral, but always about human interests. The real struggle is these never seem to be “our” human interests. As you say, either-or is just plain stupid.

Even Sheldon Adelson is for more regulation… of online gambling. Sorry, gaming.

The World Bank paper is actually here: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2014/03/25/000158349_20140325092905/Rendered/PDF/WPS6810.pdf

In substantive content the analysis is disappointing. There might be a useful methodology to help in fleshing-out Hugh’s kleptocracy concept. The paper suffers severely from ideology and misses Yves’ run-in point that regulation and deregulation lead to the same problem. Sweep away the regulation, go transparent and let the private sector doctor cure all. Arghh!

The methodology is a form of quasi-follow-the-money. There is a convincing analysis that ‘Ben Ali firms’ achieved competitive advantage by regulatory capture. A statement of the blindingly obvious.

What’s missing is any robust work on what regulatory capture might be beyond a clan that has seized power, and how deregulation might work as regulation under a new name simply favouring another set of human interests. Sequestration of the Ben Ali clan produced and estimated $13 billion, more than a quarter of Tunisian GDP in 2011.

‘In part because Tunisia registered stable positive growth rates hovering around 4–5% per annum, Ben Ali also had a fairly favorable external image. The World Economic Forum repeatedly ranked Tunisia as the most competitive economy in Africa and the IMF as well as the World Bank heralded Tunisia as a role model for other developing countries.’

Yet the country was run by a corrupt clan and Arab Spring came along to displace the Paradise. A paradise with high unemployment, hungry people and vile repression …

Research like this seems stuck in a world of pots calling kettles black. What is it we have in the West to offer? Where has any of it worked? In USUK (my partner suggests FUKUSe when we do foreign policy) One can’t even take pay from HE institutions without knowing you are living on the back of student debt.

Deep in this we don’t even understand what a level playing field is, literally. A massive advantage to teams who can afford to build them, train on level playing fields and develop the skills of playing on them. And a severe competitive disadvantage to teams I used to visit playing on a hill in Halifax or bred to excel in the hypothermia-inducing North Sea winds at Hull KR.

There is no depth definition in economics. The vapid rich occupy niche conditions subject to huge autopoetic regulation, whether the clans of Africa and the Middle East, quants doing VAR calculations on the valueless, sports stars or the business elites anywhere. We conflate everything. Sure, Rooney is a better striker than an old crock like me and I have no problem with him playing for Manchester United. At least in principle here we might construct a fair test on the niche ability under public scrutiny. Not so for a quant at Gold-digger Sachs or Jamie Dimon. And nothing explains why the filthy rich should get cascades of the money and the perversions of what they later do with it.

One might imagine this World Bank paper as examining an example of the clan-virus and that the story is the researchers’ findings apply to a disease across the finance-business sector on a global basis. In fact, the life-history leading up to killer pneumonia might be a good metaphor. First you get unpleasant viruses (‘clans’) that reduce your immunity, levelling your playing field (health) so the heavy-hitting bacteria can come in and loot the remaining prize – your life (selling you Tamiflu “protection” along the way). We might ask too, what inoculations the plague-carrying IMF and World Bank operatives have had that allows them to carry the disease, spread it and not die.

“The World Economic Forum repeatedly ranked Tunisia as the most competitive economy in Africa and the IMF as well as the World Bank heralded Tunisia as a role model for other developing countries.”

See, now that should be a tip-off. When the WB, IMF and WEF think you’re country is doing a good job, that’s usually a sign that things are going horribly wrong for the populace…or am I being overly cynical?

“However, in Tunisia, regulation was the vehicle for creating near-monopoly conditions, while in the US, deregulation and weak anti-trust enforcement have facilitated increasing concentrations of wealth and power. ”

Nay, it’s more nuanced that that. With multinationals writing the new regulatory controls, along with austerity defunding regulatory oversight that could matter, the regulatory structure becomes far less of a concern for the MNCs in the U.S. However, to ensure MNCs don’t have to face pesky small-fry competitors, regulations -do- take their toll on small firms, kicking the shit out of them until they no longer move.

The sad part is, the MNCs easily enroll the support of small firms to fight regulatory control -as if- MNCs face the same regulatory costs as small firms.

Agreed – yet we are still in the purview-language of econo-babble. MNCs, SMEs, firms, businesses – yet a whole wad of people are being regulated under regulation or deregulation. What could be more regulating on people than poverty, not being able to feed families, discovering your skills have been embodied in more efficient machines and waiting for the private sector pixies to give you a job (low skill, part-time subsidised by tax credits)?

So what is regulation-deregulation really and why does economics exclude reality?

Both regulation and deregulation have the same goals: competitiveness and productivity. Both of those goals enrich the oligarchs. Old fashioned capitalism eats itself alive by engaging in competitiveness and productivity. But we still use accounting principles that tell us an economy is doing well when the bottom line shows a profit, nevermind what was sacrificed to get it.

Some world in which the truth has to be cynical! Britain is the current IMF poster child. Good grief!

From the powerful oil barons in the USA in the 1920s to today’s oligarchs in Russia and Ukraine, entrenched interests have been a major concern over time and around the globe.

This article gets off to a bad start. 1920s? The vampire squid blood funnel thingy is sucking out our life blood right here, right now — and we need to evoke the 1920s as a case-in-point?

Haven’t read the article or the preceding comments, only the headline and lede blurb. But IMO the only cure for entrenched kleptocracy is a Reign of Terror. Put enough people under the guillotine blade and you’re sure to:

a) Get lots/most of those most deserving;

b) Deter, at least for a few decades if not a century or so, those who escape the blade from being too blatant and too over-reaching in their future activities.

This is probably all we proles get from the justice system, so why not them?

They also feel fearful and compliant if you break their stuff. Hence, the definition of terrorism currently in use by some US agencies holds threats to property on par with threats to life. i.e. the USG has quite brazenly taken a side in the class war.

It’s a crying shame people have forgotten how to down tools and demand more. If we had, most likely we wouldn’t be in desperate times.

Ok, well regulation or no regulation the name of the game is power not economics. Any economic system or markets is a function of who has power. TBTF banks thrive because they will kick some serious butt if you f–k with them and no amount of whining and complaining or appeals to change policies and regs is going to make any difference. Machiavellian rules are always in effect except in limited and rare situations when populations are more virtuous than not. The Tunisian royals will, similarly, put a hurt on Tunisians seriously threaten the power of the royals–this has nothing to do with regs–at least they have the decency to lay out the rules of the game. In this country (USA), in contrast, nobody but insiders know the real rules as per Kubrick’s last movie.

Machiavellian rules were only supposed to be in use at rare times in the republic’s life Bangor. General times were about a social contract way in front of what we have sunk to now. Of course, we could argue all night on what an ass like his was actually saying. I could throw up some quotes even from him (I take him as a realist and satirist) that would be against our current cruel condition. There’s a paper here that takes an interesting tack – http://www.santafe.edu/media/workingpapers/14-02-001.pdf

I think Susan’s ‘ But we still use accounting principles that tell us an economy is doing well when the bottom line shows a profit, nevermind what was sacrificed to get it.’ says more than the paper – but I still like its tack on the origins of our stupid economics. There’s a great, if windy quote from Mandeville:

‘Hunger, Thirst and Nakedness are the first Tyrants that force us to stir; afterwards

our Pride, Sloth, Sensuality and Fickleness are the great Patrons that promote all

Arts and Sciences, Trades, Handicrafts and Callings; while the great Taskmasters

Necessity, Avarice, Envy and Ambition … keep the Members of the Society to

their labour, and make them submit, most of them cheerfully, to the Drudgery of

their Station; Kings and Princes not excepted.’ Cue the Seven Dwarfs off to work!

Susan has a knack of cutting through the crap in a paragraph. I suspect when Bangor says ‘it’s politics’ or Hugh ‘it’s kleptocracy’ a whole world spins for those of us who agree – but we do need something more organised. Nietzsche once jibed that bourgeois morality relies on little more than being able to send the boys round to enforce debt.

The current system is so bad that I clutch at such religious straws as ‘universal justice’ and I’m an atheist scientist. I need regulation as an individual (not born good), but I want to live free. This includes such ‘trivia’ of being free of wanting to bend others to my will. Later today I’ll be covering some management gawp on leaders ‘creating reality for others’. Like unemployment as a space to look at some worthy ‘reality creator’ buying a £150K bottle of champagne to attract ‘lovely women’?

All economics has the problem that money will be given to people to control its use in resource allocation. They cheat. So we need regulation. They’re smart so they capture the regulation. Deregulation seems to prevent regulatory capture, but humans do slight-of-hand. The deregulators are a regulatory clan themselves. The certainty? We get a paid drudgery station if we’re lucky. The virtue ethics morality professor takes her pay by casting students into debt. Quite ordinary Germans took jobs in the Gestapo and Stasi. Quite ordinary Albuquerque cops shoot a guy in the back like so much vermin with their camera rolling. There’s a ‘welcoming prostitute’ waiting for me at the airport in some middle-eastern backwater (work out how you turn this down and what it actually means).

It is politics as Bangor always says. How do we get a decent politics with an accounting system that works?