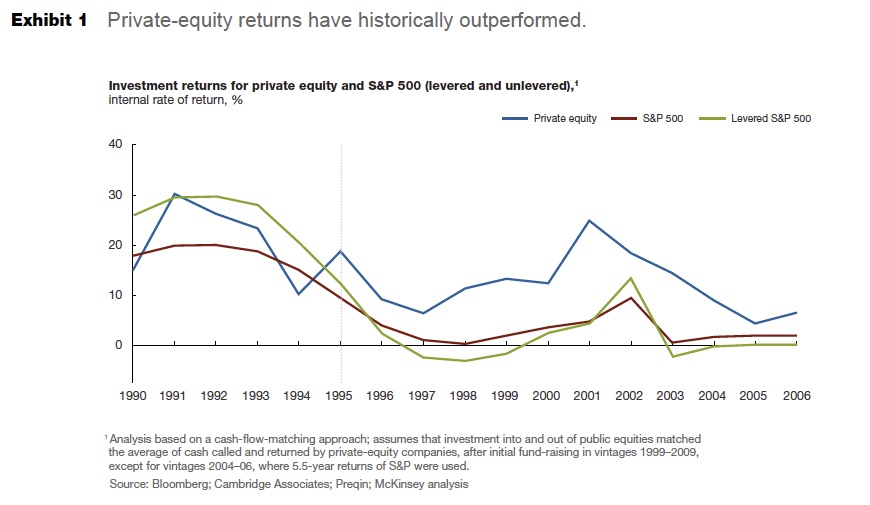

McKinsey has issued a new report on the private equity industry that ought to give any investor cause for pause. The consulting firm, which just happens to have private equity firms as as major source of revenue, is a bit too obviously engaging in porcine maquillage. The report describes enthusiastically how private equity has been an even better investment strategy than most people thought. The white paper makes only passing allusion to the fact that returns in recent years haven’t been all that good; “many general partners are struggling to raise new funds on the heels of disappointing recession-era vintages.” Industry average returns have been lower than plain old stock indexes. Notice how McKinsey omits the recent crappy years from this chart:

I’m also curious as to how they constructed that levered equity return line. Intuitively it doesn’t look right, but I don’t have a way to check the data.

By calling lower returns “recession era,” the article implies that the economy is to blame. But a more probable culprit is too much capital chasing too few promising companies. Private equity has more than doubled relative to the size of global equity markets since 2000: it was 1.5% of global equity market cap (and remember, this was the peak of the dot com bubble) and rose to 3.9% as of 2012. The competition for deals is fierce; I’ve been told for more than 7 years that any middle market company that was auctioned would get at least 40 bids. If you have to pay a full price for companies, it’s a lot harder to make juicy returns. And that raises the specter that underwhelming performance will persist.

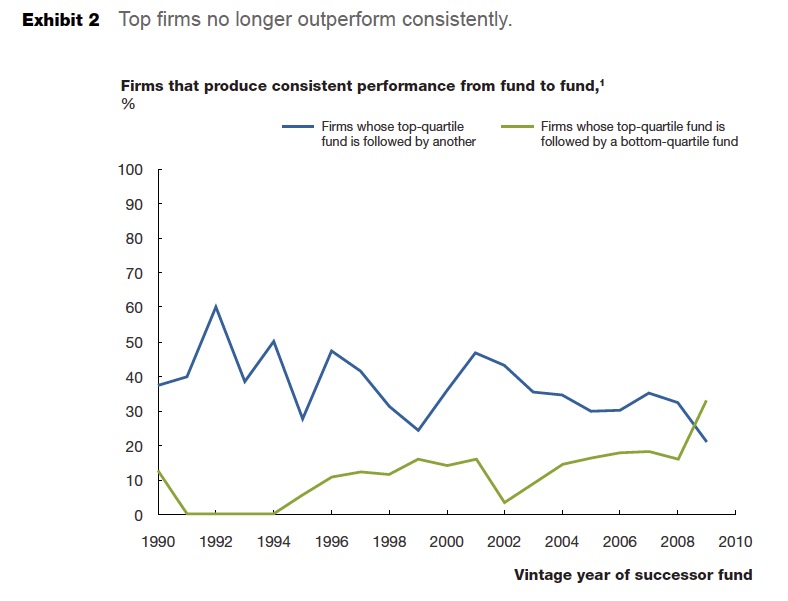

One rationale for investing in private equity has been that the top quartile funds (meaning the best 25%), showed persistent good performance. McKinsey has to admit that this justification for investing in private equity is also a thing of the past:

Other McKinsey analysis finds that the persistence of returns—in particular the tendency of top firms to replicate their performance across funds—is not nearly as strong as it once was. Until 2000 or so, private-equity firms that had delivered top-quartile returns in one fund were highly likely to do so again in subsequent funds. Knowing that yesterday’s winners were likely to excel again today enabled limited partners to focus their due diligence on identifying top-quartile funds.

Since the 2000 fund vintage, however, this persistence has fallen considerably.

Notice that McKinsey tacitly accepts that it was reasonable to believe that investors could identify and invest exclusively in these top-quartile funds. We pointed out that logical fallacy in a recent post:

Mind you, it’s not because the City of Seattle is unusual for expecting that it can consistently out-invest more than 75 percent of private equity limited partnership investors. It’s the opposite. Seattle’s investment objective is revealing because it’s the stated goal of almost all LP investors in private equity, who almost universally believe the mathematical impossibility that all of them can assemble a portfolio of PE funds that will beat the performance of three quarters of their peers.

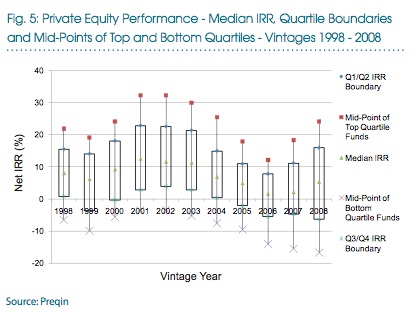

This is a typical graph that investment consultants use to justify the barmy goal that all private equity LP investors must achieve above-average results:

…When you boil it down, this graph illustrates the ugly truth of investing in private equity: it’s not attractive unless you can outrun most of your peers investing in the asset class.….

Fundamentally, this is an intellectually dishonest exercise, and diametrically opposed to the way many public pension funds construct other parts of their investment portfolios. With public equity in particular, it’s almost certain that a significant majority of U.S. pension fund assets are invested in index funds. That’s because pension funds have recognized that, collectively, they cannot do better than average, and that after paying active management fees, actively managed public equity portfolios typically perform worse than the market average.

So it’s not as if these investors are so clueless that they can’t grasp the point that all of them cannot achieve above average results, let alone significantly above average results. Instead, with private equity, there is a desperate desire to be in the asset class for reasons that probably reflect a combination of intellectual capture by the PE managers, political corruption in legislatures that control public fund board appointees, and the need to have a strategy that could conceivably solve the pension underfunding problem over time.

Another reasons why investors would legitimately find it hard to figure out who the real winners had been: the industry, as McKinsey acknowledges, is very secretive about returns. That made it possible for nearly 80% of the incumbents to claim they had achieved top quartile performance by artfully defining who was in the universe against which they were compared.

So whar does the mighty McKinsey recommend? Effectively, it falls in line with the PE firms by urging investors to focus on more narrowly-defined strategies. The logic is that private equity funds with a skill advantage can still deliver sparkling results. For instance, the firm’s research has found that firms with more financiers on their bench do better at roll-ups, while those who have mainly consultants or former operators on their team are more successful in wringing operating improvements out of their portfolio companies.

But focusing on more narrow strategies supports the industry ruse of cherry picking who they should be measured against. And it also means that investors are supposed to judge if the private equity general partners have the acumen to deliver on their special strategy better than their peers. Every study of hiring says it’s a hit or miss proposition, and remember, when you are hiring for your own business, you actually know, or should know, your business better than anyone. Private equity limited partners, almost without exception, have never been in the PE business and thus are relying on proxies, which means they can misjudge or be misled or misjudge.

What other advice does McKinsey offer? The white paper describes how some limited partners have earned even better returns by going into the private equity business themselves. But after acknowledging their success, McKinsey spends even more time telling readers how terribly daunting this is to pull off.

The paper also encourages limited partners to look into “more nascent markets and to adjacent asset classes”. But that contracts their advice about being even more stringent in evaluating private equity general partner capabilities. Expertise in one arena doesn’t necessarily translate into another. And by definition, entrants into a “nascent market” have little to no track record. For instance, we’ve mentioned the fact that the venture capital firms Sequoia and Kleiner Perkins have refused to let public pension funds, which are subject to state Freedom of Information Act laws, into their funds because they might publish some of their return information.* In the case of Sequoia, that may be due to the fact that Sequoia has launched funds in India and China that are widely believed to have performed poorly. Why would you invest in Sequoia’s third China fund if you knew that the first two were dogs?

But instead of saying that these developments call into question the rationale for investing in private equity, McKinsey instead gives a “dare to be great” speech:

To make these assessments, limited partners will need to generate deeper insights into the drivers of private-equity performance, follow these insights to identify high-potential geographies and sectors, and have the conviction to use these insights to select external managers.

Translation: limited partners will need to find new rationales for how they throw darts at private equity investments. And if you wind up being lucky, you can tell yourself you were actually smart!

The fact that McKinsey has to resort to such strained justifications should be a big red flag. The whole point of such artful wording is to show McKinsey standing shoulder to shoulder with a very important client base while still giving all the right caveats, since its imprimatur will also help justify continued high levels of investment in this strategy. After all, as Keynes said:

A “sound” banker, alas! is not one who foresees danger, and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional and orthodox way along with his fellows, so that no one can readily blame him…Life-long practices of this kind make them the most romantic and the least realistic of men.

That mindset makes investors vulnerable to the blandishments of McKinsey and fund consultants, that they are clever and insightful enough to do a better job of manager picking than everyone else who has money to burn.

_____

* There have been exceptions, but these funds have had to agree to not keep performance data on their premises, and to be able to view it only on a limited basis by visiting the premises of the general partners.

Maam;

I liked the reference to the famous “Wall Street Journal Dartboard” method of stock investing. If I remember rightly, didn’t the Dartboard outperform the general run of analysts? How is the Dartboard doing lately? (An Aurora Advisors “Randomized Investments Fund” might be a good idea. Craazyman can throw the ten darts at the next Meetup. Put me down for a sawbuck!)

Another method is to place the appropriate pages of the WSJ on the bottom of your bird cage and put your money wherever Polly puts her poo. So far, I’ve earned top decile returns in every year I’ve implemented this strategy (when measured against the universe of other investing avians).

‘After paying active management fees, actively managed public equity portfolios typically perform worse than the market average.’

This is the fundamental fact that they can’t get around. Fees eat away the equity premium which compensates for the risk of owning equities.

PE is a subset of active management (vs. passive management by owning an index). Decades of studies show that active managers as a group can’t beat passive management in public equities.

Private equity is surely the same, but the data needed to prove it (as shown by Yves’ travails with Calpers) is kept secret.

Private equity: an undertaking of great advantage, but no one to know what it is!

Or as P. T. Barnum would say if he worked for Kleiner Perkins: ‘This way to the egress!’

In the old days McKinsey wasn’t afraid to piss off its clients. They once sent Booz, Allen’s head beltway bandit storming out of the room by imparting the same home truth – in the end you don’t do much better than your industry does.

Slow clap for the Glen Turner reference. How profoundly insulting to the painstakingly-instilled status anxiety of the McKinsey meritocrats!

Think of the old Monty Python poverty joke. ‘We lived in a shoe box on the central reservation of the M6 … you had a shoe box? Luxury’.

‘You have darts’? And, of course, the parrot will be a dead parrot and unable to do the Wall Street squeeze.

McKinsey first came to my attention doing some NHS research. In literature survey I found a report from them saying US health care was the best in the world and only expensive because US research and development subsidised the rest of the world.

McKinsey poison is driven by a fascist idea of human beings as a resource (HRM with whips). We can judge companies by how much money they make per employee. Private Equity Funds are the modern equivalent of joint stock ventures to equip ships to go pirating, guano exploiting and slaving.

The stock market is odd. If you bet on all the horses in a race you merely enter a Dutch Book, guaranteed to lose. This will be true of the dart or parrot dung approaches in dead donkey betting too. It does seem, on average, that experts are no better than blind dartsmen (efficiency note: sack the men, parrots would be cheaper). At first sight, people like Warren Buffet, seem to break this rule. But go to the races and you’ll find non-bookie winners on the day. The ‘average’ implies a frequency distribution. We mugs who can barely afford a set of darts or a viable parrot will find very high fees extracted from our punts.. High rollers get discounts and better food, drink and prostitutes in casinos. We all lose to the bookies, who take risk-free fees. What would McKinsey’s role be in this?

The stock market is a very long-game Ponzi. Inflation goes some way in explaining how we get pay-outs, as do the recent welfare bail-outs-and-ins. But what else might be missing from McKinsey graphology? Aren’t there people actually doing work somewhere? Being ripped-off? It strikes me that, if we were farming sheep, the first part of our plan would not be to introduce wolves into the hinterland. Time to cull these predators. Predators generally take out the disabled, infirm, old and so on. McKinsey rot is based on carving-up the best, so even their ‘hygiene’ claims are false. Have you seen how their consultants dress? It’s like a cross between American Psycho and Belle du Jour. What’s missing from their graphs is any respect for data at all.

The PE industry is like any other abstract purchase business: it starts with a sales job, is maintained by a snow job, and ends with the customer getting… Ah, well, yes.

The McKinsey report might work as the centerpiece of a PE fund sales patter. True or not, it says the right things and the managers and officials in charge of placing large amounts of OPM need to hear the right things. Whether they’re in on the joke or they’re really the country boy staring wide-eyed at the latest and greatest, they can take up the patter and use it to defend their actions.

Important people are too busy to follow the asterisk to the footnote, so the broad promise is all they get. Craft the phrase well enough, and they could use it for any occasion.

Fun-nee. Falling back on romanticism. That’s Karma. It’s pretty challenging to dare vultures to be great. After all, everything tastes like chicken.

Never tried vulture. Probably the only ‘animals’ I’d shoot knowing I wouldn’t eat them. Scraps point on it not really mattering whether the audience for McKinsey is country boy or in on the joke seems spot on. I don’t believe anyone with a moral compass can believe in asset stripping and cash-cow milking for the 1%. So I’d offer therapy, explaining how expensive this is whilst handing over some cheap vodka and a pistol.

They took everything away from the bottom 80%, now they are moving up to the top 20 to 10%… their DB pension plan.

My forecast is that nothing will happen until the top 10% gets fooled… all the top 10%ers around me love to emphasize that they are not their brother’s keeper, their motto is take care of number one because nobody will.

I’m always amazed that the S&P 500 is used as a proxy for PE. With a weighted average market cap of $120B, the average S&P company is several orders of magnitude larger than the average PE company. However, the S&P helpfully experienced bubble valuations in the 1990s, making it a no brainer as the benchmark of choice for marketing purposes.

Plug in something like the Russsell 2000 Value on a leverage adjusted basis and let’s see how much skill is out there on an industry-wide basis.