By Philip Pilkington, a writer and research assistant at Kingston University in London. You can follow him on Twitter @pilkingtonphil. Originally published at Fixing the Economists

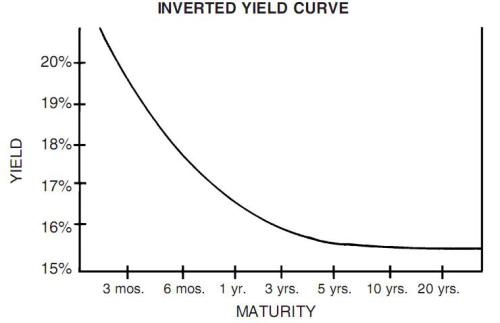

One of the nicest stylised facts in applied economics is that if the Fed inverts the yield curve it will cause a recession. Inverting the yield curve basically means that the Fed hikes the short-term interest rate goes higher than the long-term interest rate. In theory this should lead to long-term lending drying up, investment falling significantly (usually in housing and inventories) and, ultimately, a recession.

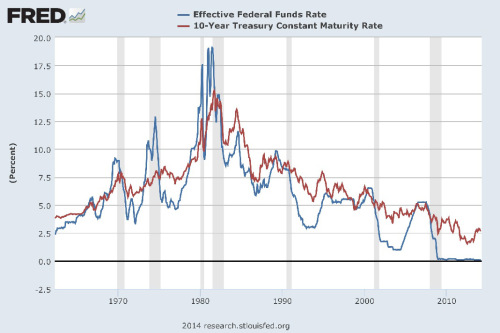

The track record of this as an indicator of recessions in the US is too impressive to dismiss. Take a look at the chart below. The shaded areas are recessions. As you can see, every time the short-term interest rate (blue line) climbs about the long-term interest rate (red line) we see a recession within around 12 months or so.

The question, however, is whether this is universal economic constant. And when we turn to the data from other countries we quickly see that it is not.

All the data that follows if from the St. Louis Fed but I have done the graphs myself so that I could include lines indicating British and Japanese recessions.

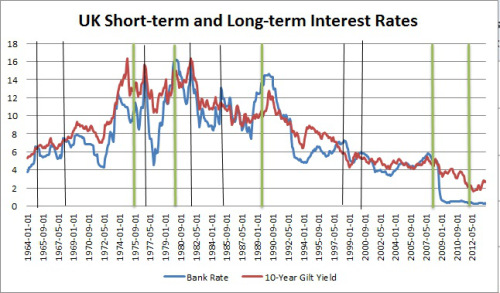

Okay, so let’s take the UK first. This graph is pretty rough but the green lines are the starts of recessions and the thinner black lines are points when the short-term interest rate rose above the long-term interest rate without causing a recession. The short-term interest rate is the blue line and the long-term interest rate is the red line.

As we can see, the story here is a bit more complicated than in the US. Only three out of the five recessions were precipitated by an inverted yield curve. Meanwhile the yield curve inverted seven times without causing a recession.

This does not bode well for the notion that this correlation might be constant across time and space.

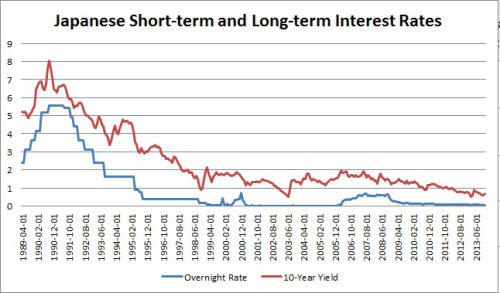

So, let’s turn to Japan. Unfortunately, the data available for Japan is only from during the so-called Lost (Two) Decade(s) and so we will be dealing with a rather unusual period. Nevertheless, it should still prove interesting.

As the reader can see I have not bothered to mark the recessions in this chart. Why? Because it is quite clear that the yield curve never inverted in this period. The short-term interest rate (blue) always stayed below the long-term interest rate (red). What’s more, in this period Japan had five recessions. Including a massive one at the beginning of the 1990s. Clearly these were not correlated with and therefore not caused by an inverted yield curve.

So, the question remains: why is this correlation so strong in the US? This is impossible to answer without some doubt but allow me to shoot from the hip a little and throw out some potential causes. (Suggestions welcome in the comments!)

1. The US is a very insulated economy: due to this recessions are caused largely by internal factors.

2. The US economy is more credit-driven than other economies: hence, the interest rate plays a larger role in investment and consumption decisions.

3. The US has tended to use monetary policy more consistently than its neighbors: which is why the economy has become more ‘used’ to falling into recession when monetary policy is aggressively tightened.

4. There is a self-fulfilling belief in the US that an inverted yield curve leads to recessions.

Frankly, I think that the answer lies somewhere in between the four reasons listed above. I think that reason number four is also probably the most important. Folks in the US get very hot and bothered about inverted yield curves — reflecting the American love for projecting engineering-like causality into just about every field — and this likely has a sort of ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ effect.

Anyway, whatever the reason the facts are clear: the rule-of-thumb that a recession will generally follow on the back of an inverted yield curve is a good one for the US — whether it is based on hocus pocus or otherwise — but it is probably useless to apply outside of the US. Once again we learn that time-tested lesson: there are no universal laws in that all-too historical field known as economics.

The yield curve inversion worked in the U.S. post-WWII economy as well as it did, because it operated against mortgage-financing of housing, which relied on 30-year, fixed-rate mortgages.

But, certain aspects of the mechanism are arguably universal: inverting the yield curve squeezes the carry trade, in which banks are engaged, when they use a demand deposit base to supply credit tied to long-term rates. Carry trades arise in many other institutional settings, though it was very powerful in the U.S. because of the institutional structure of residential housing finance.

I’d be cautious about throwing out the baby with the bathwater, here. One of the most pernicious myths of mainstream economics is the idea that it is OK to imagine that there is a single interest rate, acting as a valve regulating a flow of loanable funds, and reflecting a time-preference. That’s all rubbish, but it is hard to get away from it.

Focusing on the yield curve as a policy lever reveals the important truth that there is a great range of interest rates, and many important policy effects are the product of relative interest rates, and the product of arbitrage by banks and financial market players, not some effable time-preference.

True, various rates can produce varying incentives depending on the historical context. Banks earning their profits from exploiting a yield spread can suddenly find themselves forced to rely on making more loans if the spread contracts. So in that case you could get a credit boom and faster growth along with more private debt. It’s questionable that one can draw any generalized conclusions from past changes to monetary policies as the variables are so complex.

I like this post – and at the same time agree with a lot of what Bruce Wilder is saying.

However, for me, the key element here is no. 1.

For the time periods in question, the US is the most independent (rather than insulated) economy in the world. That interacts with no. 2 – not only is credit very important in the US economy, most of that credit is “in-country” credit – and thus most affected by changes at the Central Bank.

By contrast, other countries are much more likely to have recessions because of problems with trading partners, and/or the regional finance hub and/or international finance. The UK is a great example, with the 70s recessions violating the hypothesis – but those recessions relate to problems (badly solved, from an MMT point of view) with financing debt on international markets.

Of course, once debt is “overhanging” you get perma-recession, no matter how you fiddle with interest rates, as illustrated by Japan.

I guess in the process of this comment, what occurs to me is that a lot of this is about (4) but with a reverse causality. There’s something in the psychology of US Central Banking that means they respond to other kinds of economic crisis by fiddling with the interest rate. (That’s part of what you are saying in (3) but subtly different.) Key here is that the causality runs in different directions. No-one would actually argue that the 70s recessions weren’t partly about the oil shock. Likewise, surely no-one would argue that the recent financial crisis was about the yield curve. So, the conclusion is – you can create an interest rate recession (e.g. Volker) but other recession reasons exist – what’s special about the USA is that when external factors cause a recession, they fiddle with interest rates in ways that so far, always invert the yield curve…

‘No-one would argue that the recent financial crisis was about the yield curve.’

One could argue that Fed policy consistently lags and overshoots, which of course shows up in the yield curve.

For instance: the bespectacled charlatan Greenspan not only held the Fed funds rate at one percent until mid-2004 (when both an economic recovery and a formidable housing bubble were apparent to all but the purblind), the mumbling fool extolled the virtues of ARM mortgages to millions of victims who swallowed his poisoned bait.

Greenspan, followed by Bernanke, proceeded to hike the Fed funds rate from 1.00% to 5.25% in two years. Though it was done in 17 quarter-point baby steps, this multiple-of-five hike in short rates was by far the most extreme in U.S. history. At the time I claimed that the steep rate-of-rise constituted a harsh shock to the economy, and so it did.

Now we are back where we were in mid-2004, except that instead of ‘one percent forever’ it’s ‘zero percent forever,’ backed by the unsprinklered munitions warehouse of a tripled Fed balance sheet. When this damn-fool booby trap blows sky high, let’s hope it takes the Fed as an institution down with it.

This article raises a very important point, that all economies are different and therefore respond differently to the same policy. The classic example demonstrated here is that the US is a nation of spenders and hence very sensitive to interest rates. Japan used to be the opposite, in the 1990s it was a nation of savers, so its policy response should have been to increase interest rates and increase the return on Mrs Watanabe’s formidable deposits which would, all else being equal, have increased consumer spending. However, higher interest rates would have killed most of the zombie companies that banks supported, so Mrs Watanabe’s husband would have lost his job. This would have forced the economy to restructure far earlier than it did – out with the window-gazing tribe, in with temporary contracts – which would possibly have been unacceptable politically and therefore unworkable.

It is also very clear how terrible is the economic structure of the EU with its single currency and interest rates applied across widely ranging economies. For example, German home ownership is below 50% whereas Spanish ownership used to be 82%. How do you set a single rate that matches the conditions in both countries simultaneously? You can’t.

Part of the problem is that the rules that have been created are seen as the end whereas they are in reality a means to an end – which is greater union. So there was a suggestion that, instead of allowing Greece or Portugal to devalue to solve their economic problems, their tax systems could be used to introduce a similar effect to devaluation. Hence raise taxes on imports and cut taxes on exports. (Germany, of course, should today be doing the opposite). But such proposals stand no chance of being accepted as they breach all sorts of shibboleths about “level playing fields” and “single markets”. But which set of policies would have produced better outcomes? Is the unemployment in Europe a good result?

Finally, as economies differ between each other and respond differently to the same policy, so they change over time, and their response to the same policy will vary. For example, it is clear that the US and UK economies are much more sensitive today to interest rates as their banking sectors have expanded enormously and private debt has risen substantially. China and the Communist bloc are now much larger and formidable economic forces. The consequence is that this makes it difficult, if not impossible, to use historical information to project future policy. So while broad comparisons may be made over long periods of time, detailed conclusions are very dangerous to make.

So how can we change the failed conventional economic wisdom?

To what extent might self-fulfilling prophecy (business media repeating the correlation as a rule of thumb and investment advice) be a factor here?