Yves here. Regular readers will notice that this post overlaps somewhat with Grommen’s post last week, The Dow Jones Industrial Average is a Hoax, but this article is broader and makes more fundamental arguments. One bone of contention is that in one chart, he conflates government debt on gold standard or equivalent terms with a fiat currency. And I suspect NC readers will have strong points of view on his claim at the end regarding the foundations of a stable society. Nevertheless, I thought this article would serve as useful grist for thought and discussion.

By Wim Grommen, a teacher in mathematics and physics and later a trainer of programmers in Oracle software. He has also studied and written about transitions, social transformation processes, the S-curve and transitions in relation to market indices. Originally presented at an international symposium in Valencia: “The Economic Crisis: Time for a Paradigm Shift”

ABSTRACT

This paper advances a hypothesis of the end of the third industrial revolution and the beginning of a new transition. Every production phase or civilization or human invention goes through a so- called transformation process. Transitions are social transformation processes that cover at least one generation. In this paper I will use one such transition to demonstrate the position of our present civilization. When we consider the characteristics of the phases of a social transformation we may find ourselves at the end of what might be called the third industrial revolution. The paper describes the four most radical transitions for mankind and the effects for mankind of these transitions: the Neolithic transition, the first industrial revolution, the second industrial revolution and the third industrial revolution.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) Index is the only stock market index that covers both the second and the third industrial revolution. Calculating share indexes such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average and showing this index in a historical graph is a useful way to show which phase the industrial revolution is in. Changes in the DJIA shares basket, changes in the formula and stock splits during the take-off phase and acceleration phase of industrial revolutions are perfect transition-indicators. The similarities of these indicators during the last two revolutions are fascinating, but also a reason for concern. In fact the graph of the DJIA is a classic example of fictional truth, a fata morgana.

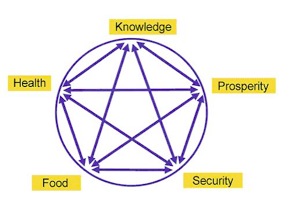

History has shown that five pillars are essential in a stable society: Food, Security, Health, Prosperity and Knowledge. At the end of every transition the pillar Prosperity is threatened. We have seen this effect at the end of every industrial revolution. Societies will have to make a choice for a new transition to be started.

1 INTRODUCTION

Every production phase or civilization or other human invention goes through a so-called transformation process. Transitions are social transformation processes that cover at least one generation. In this paper I will use one such transition to demonstrate the position of our present civilization. When we consider the characteristics of the phases of a social transformation we may find ourselves at the end of what might be called the third industrial revolution. Transitions are social transformation processes that cover at least one generation (= 25 years).

A transition has the following characteristics:

– It involves a structural change of civilization or a complex subsystem of our civilization

– It shows technological, economical, ecological, socio cultural and institutional changes at different levels that influence and enhance each other

– It is the result of slow changes (changes in supplies) and fast dynamics (flows)

Examples of historical transitions are the demographical transition and the transition from coal to natural gas which caused transition in the use of energy. A transition process is not fixed from the start because during the transition processes will adapt to the new situation. A transition is not dogmatic.

2 TRANSITIONS

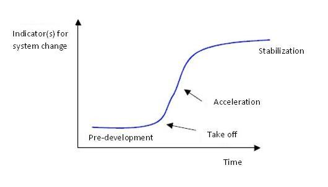

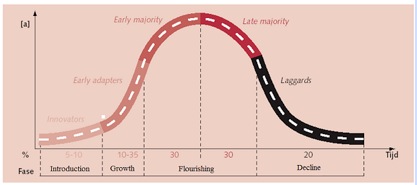

In general transitions can be seen to go through the S curve and we can distinguish four phases (figure 1):

1. A pre development phase of a dynamic balance in which the present status does not visibly change

2. A take off phase in which the process of change starts because of changes in the system

3. An acceleration phase in which visible structural changes take place through an accumulation of socio cultural, economical, ecological and institutional changes influencing each other; in this phase we see collective learning processes, diffusion and processes of embedding

4. A stabilization phase in which the speed of sociological change slows down and a new dynamic balance is achieved through learning

A product life cycle also goes through an S curve. In that case there is a fifth phase:

the degeneration phase in which cost rises because of over capacity and the producer will finally withdraw from the market.

Figure 1. The S curve of a transition

Four phases in a transition are best visualized by means of an S curve: Pre-development, Take-off, Acceleration, Stabilization.

The process of the spreading of transitions over civilizations is influenced by a number of elements:

• Physical barriers: oceans, deserts, mountain ranges, swamps, lakes

• Socio-cultural barriers: difference in culture and languages

• Religious barriers

• Psychological barriers

When we look back over the past, we see four transitions taking place with far-reaching effects.

2.1 THE NEOLITHIC TRANSITION

The Neolithic transition was the most radical transition for mankind. This first agricultural revolution (10000 – 3000 BC) forms the change from societies of hunter gatherers (20 – 50 people) close to water with a nomadic existence to a society of people living in settlements growing crops and animals. A hierarchical society came into existence. Joint organizations protected and governed the interests of the individual. Performing (obligatory) services for the community could be viewed as a first type of taxation. Stocks were set up with stock management, trade emerged, inequality and theft. Ways of administering justice were invented to solve conflicts within and between communities and war became a way of protecting interests.The Neolithic revolution started in those places that were most favorable because of the climate and sources of food. In very cold, very hot or dry areas the hunter gatherer societies lasted longer.

Several areas are pointed out as possible starting points: southern Anatolia, the basins the Yangtze Kiang and Yellow river in China, the valley of the Indus, the present Peru in the Andes or what is now Mexico in Central America. From these areas the revolution spread across the world. The start of the Neolithic era and the spreading process are different in each area. In some areas the changes are relatively quick and some authors therefore like to speak of a Neolithic revolution. Modern historians prefer to speak of the Neolithic evolution. They have come to realize that in many areas the process took much longer and was much more gradual than they originally thought.

2.2 THE FIRST INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The first industrial revolution lasted from around 1780 tot 1850. It was characterized by a transition from small scale handwork to mechanized production in factories. The great catalyst in the process was the steam engine which also caused a revolution in transport as it was used in railways and shipping. The first industrial revolution was centered around the cotton industry. Because steam engines were made of iron and ran on coal, both coal mining and iron industry also flourished.

Britain was the first country that faced the industrial revolution. The steam engine was initially mainly used to power the water pumps of mines. A major change occurred in the textile industry. Because of population growth and colonial expansion the demand for cotton products quickly increased. Because spinners and weavers could not keep up with the demand, there was an urgent need for a loom with an external power unit, the power loom.

A semi-automatic shuttleless loom was invented, and a machine was created that could spin several threads simultaneously. This “Spinning Jenny”, invented in 1764 by James Hargreaves, was followed in 1779 by a greatly improved loom: ‘Mule Jenny’. At first they were water-powered, but after 1780 the steam engine had been strongly improved so that it could also be used in the factories could be used as a power source. Now much more textiles could be produced. This was necessary because in 1750, Europe had 130 million inhabitants, but in 1850 this number had doubled, partly because of the agricultural revolution. (This went along with the industrial revolution; fertilizers were imported, drainage systems were designed and ox was replaced by the horse. By far the most important element of the agricultural revolution was the change from subsistence to production for the market.). All those people needed clothing. Thanks to the machine faster and cheaper production was possible and labor remained cheap. The textile industry has been one of the driving forces of the industrial revolution.

Belgium becames the first industrialized country in continental Europe. Belgium was “in a state of industrial revolution” under the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte. The industrial centers were Ghent (cotton and flax industries), Verviers (mechanized wool production), Liège (iron, coal, zinc, machinery and glass), Mons and Charleroi. On the mainland, France and Prussia followed somewhat later. In America the northeastern states of the United States followed quickly.

After 1870 Japan was industrialized as the first non-Western country. The rest of Europe followed only around 1880.

The beginning of the end of this revolution was in 1845 when Friedrich Engels, son of a German textile baron, described the living conditions of the English working class in “The condition of the working class in England“.

2.3 THE SECOND INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The second industrial revolution started around 1870 and ended around 1930. It was characterized by ongoing mechanization because of the introduction of the assembly line, the replacement of iron by steel and the development of the chemical industry. Furthermore coal and water were replaced by oil and electricity and the internal combustion engine was developed. Whereas the first industrial revolution was started through (chance) inventions by amateurs, companies invested a lot of money in professional research during the second revolution, looking for new products and production methods. In search of finances small companies merged into large scale enterprises which were headed by professional managers and shares were put on the market. These developments caused the transition from the traditional family business to Limited Liability companies and multinationals.

The United States (U.S.) and Germany led the way in the Second Industrial Revolution. In the U.S. there were early experiments with the assembly line system, especially in the automotive industry. In addition, the country was a leader in the production of steel and oil. In Germany the electricity industry and the chemical industry flourished. The firms AEG and Siemens were electricity giants. German chemical companies such as AGFA and BASF had a leading share in the production of synthetic dyes, photographic and plastic products (around 1900 they controlled some 90% of the worldwide market). In the wake of these two industrial powers (which soon surpassed Britain) France, Japan and Russia followed. After the Second Industrial Revolution more and more countries, on more continents, experienced a more or less modest industrial development. In some cases, the industrialization was taken in hand by the state, often with coarse coercion – such as the five-year plans in the Soviet Union.

After the roaring twenties the revolution ended with the stock exchange crash of 1929. The consequences were disastrous culminating in the Second World War.

2.4 THE THIRD INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The third industrial revolution started around 1940 and is nearing its end. The United States and Japan played a leading role in the development of computers. During the Second World War great efforts were made to apply computer technology to military purposes. After the war the American space program increased the number of applications. Japan specialized in the use of computers for industrial purposes such as the robot.

From 1970 the third industrial revolution continued to Europe. The third industrial revolution was mainly a result of a massive development of microelectronics: electronic calculators, digital watches and counters, the compact disc, the barcode etc. The take off phase of the third industrial revolution started around 1980 with the advent of the microprocessor. The development of the microprocessor is also the basis of the evolution and breakthrough of computing. This had an impact in many areas: for calculation, word processing, drawing and graphic design, regulating and controlling machines, simulating processes, capturing and processing information, monetary transactions and telecommunications. The communication phase grows enormously at the beginning of the new millennium: the digital revolution. According to many analysts now a new era has emerged: that of the information or service economy. Here the acquisition and channeling of information has become more important than pure production. By now computer and communication technology take up an irreplaceable role in all parts of the world. More countries depend on the service sector and less on agriculture and industry.

2.5 EFFECTS OF THREE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTIONS

The first (and second revolution) transformed an agricultural society into an industrial society where mechanization (finally) relieved man of physical labor. The craft industry could not compete with the factories that put products of the same or even better quality on the market at a lower price. The result was that many small businesses went bankrupt and the former workers went to work in the factories. The effects of industrialization were seen in the process of rapid urbanization of formerly relatively small villages and towns where the new plants came. These turned into dirty and unhealthy industrial cities. Still people from the country were forced to go and work there. Because of this a new social class emerged: the workers, or the industrial proletariat. They lived in overcrowded slums in poor housing with little sanitation. The average life expectancy was low, and infant mortality high. The elite accepted the filth of the factories as the inevitable price for their success. The chimneys were symbols of economic power, but also of social inequality. You see this social inequality appear after each revolution. The gap between the bottom and the top of society becomes very large. Eventually there are inevitable responses that decrease this gap. It could be argued that the Industrial revolutions have created the conditions for a society with little or no poverty.

The third revolution transformed an industrial society into a service society. Where mechanization man relieved of physical labor, the computer relieved him of mental labor. This revolution made lower positions in industry more and more obsolete and caused the emergence of entirely new roles in the service sector.

3 INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTIONS AND STOCK MARKET INDICES

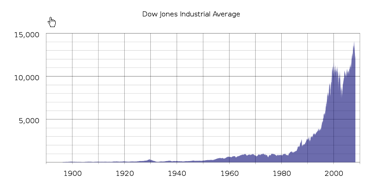

The Dow Jones Industrial Average was first published halfway through the second Industrial Revolution, in 1896. The Dow Jones Industrial Average Index is the oldest stock index in the United States. This was a straight average of the rates of twelve shares. A select group of journalists from The Wall Street Journal decide which companies are part of the most influential index in the world market. Unlike most other indices the Dow is a price-weighted index. This means that stocks with high absolute share price have a significant impact on the movement of the index.

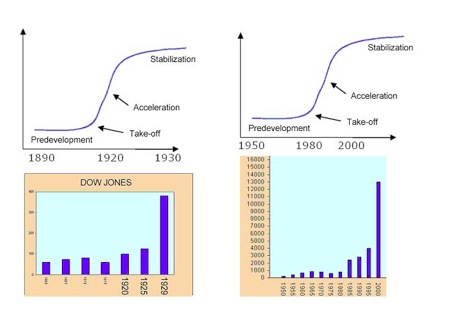

Figure 2. Exchange rates of Dow Jones Industrial Average during the latest two industrial revolutions. During the last few years the rate increases have accelerated enormously.

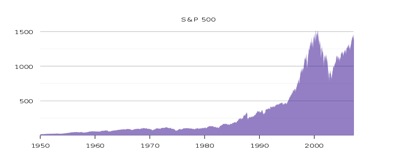

The S & P Index is a market capitalization weighted index. The 500 largest U.S. companies as measured by their market capitalization are included in this index, which is compiled by the credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s.

Figure 3. Third industrial revolution and the S&P 500

3.1 WHAT DOES A STOCK EXCHANGE INDEX LIKE DOW JONES OR S&P 500 REALLY MEAN?

In many graphs the y-axis is a fixed unit, such as kg, meter, liter or euro. In the graphs showing the stock exchange values, this also seems to be the case because the unit shows a number of points. However, this is far from true! An index point is not a fixed unit in time and does not have any historical significance. Unfortunately many people attach a lot of value to these graphs which are, however, very deceptive.

An index is calculated on the basis of a set of shares. Every index has its own formula and the formula results in the number of points of the index. However, this set of shares changes regularly. For a new period the value is based on a different set of shares. It is very strange that these different sets of shares are represented as the same unit.

After a period of 25 years the value of the original set of apples is compared to the value of a set of pears. At the moment only 6 of the original 30 companies that made up the set of shares of the Dow Jones at the start of the take-off phase of the last revolution are still present.

Even more disturbing is the fact that with every change in the set of shares used to calculate the number of points, the formula also changes. This is done because the index which is the result of two different sets of shares at the moment the set is changed, must be the same for both sets at that point in time. The index graphs must be continuous lines. For example, the Dow Jones is calculated by adding the shares and dividing the result by a number. Because of changes in the set of shares and the splitting of shares the divider changes continuously. At the moment the divider is 0.132319125 but in 1985 this number was higher than 1. An index point in two periods of time is therefore calculated in different ways:

Dow1985 = (x1 + x2 + ……..+x30) / 1

Dow2012 = (x1 + x2 + …….. + x30) / 0,132319125

In the nineties of the last century many shares were split. To make sure the result of the calculation remained the same both the number of shares and the divider changed. An increase in share value of 1 dollar of the set of shares in 2012 results is 7.5 times more points than in 1985. The fact that in the 1990-ies many shares were split is probably the cause of the exponential growth of the Dow Jones index. At the moment the Dow is at 13207 points. If we used the 1985 formula it would be at 1760 points.

The most remarkable characteristic is of course the constantly changing set of shares in during the take-off and acceleration phase of a revolution. Generally speaking, the companies that are removed from the set are in a stabilization or degeneration phase. Companies in a take-off phase or acceleration phase are added to the set. This greatly increases the chance that the index will rise rather than go down. This is obvious, especially when this is done during the acceleration phase of a transition. From 1980 onward 7 ICT companies (3M, AT&T, Cisco, HP, IBM, Intel, Microsoft), the engines of the latest revolution were added to the Dow Jones and 5 financial institutions, which always play an important role in every revolution.

This is actually a kind of pyramid scheme. All goes well as long as companies are added that are in their take-off phase or acceleration phase. At the end of a transition, however, there will be fewer companies in those phases.

Figure 4. The two most recent revolutions and the Dow. The stock value increase has accelerated enourmously during the acceleration phase of a revolution.

3.2 STOCK MARKET BOOMS

The Dow was first published in 1896. The Dow was calculated by dividing the sum of the 12 component company stocks by 12:

Dow-index_1896 = (x1 + x2+ ……….+x12) /12

In 1916 the Dow was enlarged to 20 companies; 4 were removed and 12 added:

Dow-index_1916 = (x1 + x2+ ……….+x20) /20

The shares of a number of companies were split in 1927, and for those shares a weighting factor was introduced in the calculation. The formula is now as follows (x1 = American Can is multiplied by 6, x2 = General Electric by 4 etc. )

Dow-index_1927 = (6.x1 + 4.x2+ ……….+x20) /20

On 1 October 1928 the Dow was further enlarged to 30 stocks. Because everything had to be calculated by hand, the index calculation was simplified. The Dow Divisor was introduced. The index was calculated by dividing the sum of the share values by the Dow Divisor. In order to give the index an uninterrupted graph the Dow Divisor was given the value 16.67.

Dow-index_Oct_1928 = (x1 + x2+ ……….+x30) /Dow Divisor

Dow-index_Oct_1928 = (x1 + x2+ ……….+x30) /16.67

Since then the Dow Divisor has acquired a new value every time there has been a change in the component stocks, with a consequent change in the formula used to calculate the index. This is because at the moment of change the results of two formulas based on two different share baskets must give the same result. When stocks are split the Dow Divisor is changed for the same reason.

In autumn 1928 and spring 1929 there were 8 stock splits, causing the Dow Divisor to drop to 10.47.

Dow-index_Sep_1929 = (x1 + x2+ ……….+x30) /10.47

From that moment on a an increase (or decrease) of the set of shares results in almost three times as many (or fewer) index points as a year before. In the old formula the sum would have been divided by 30. The Dow’s highest point is on 3 September 1929 at 381 points.

So the extreme increase followed by an extreme decrease of the Dow in the period 1920 – 1932 was primarily caused by changes to the formula, the constant changes to the set of shares during the acceleration phase of the second industrial revolution and splitting of shares during this period. Because of these changes in the Dow investors were wrong footed. The companies whose shares constituted the Dow index at that time also continued into the stabilization and degeneration phase.

After the stock market crash of 1929, 18 companies were replaced in the Dow and the Dow Divisor got the value 15.1.

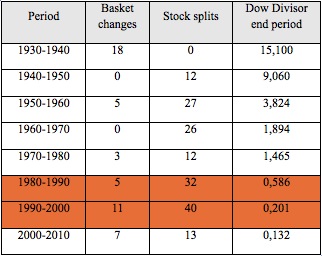

Table 1. Changes in the Dow, stock splits and the value of the Dow Divisor after the market crash of 1929

The table makes it clear that the Dow Jones formula has been changed many times and that the Dow Divisor in the period 1980-2000 (take off phase and acceleration phase of the third revolution ) and has actually become a Dow Multiplier, due to the large number of stock splits in that period. Where in the past the sum of the share values was divided by the number of shares, nowadays the sum of the share values multiplied by 7.5. Dividing by 0.132 is after all the same as multiplying by 7.5. (1 / 0,132 = 7,5). This partly explains the behaviour of the Dow graph since 1980.

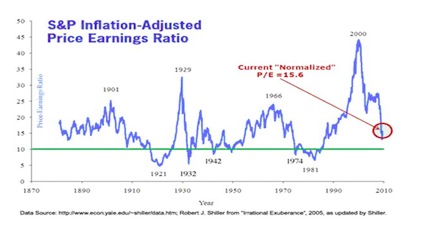

3.3 SHARE PRICE / INCOME RATIO DURING AN INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

During the pre-development phase and the take-off phase of a revolution many new companies spring into existence. During the acceleration phase of a revolution it will be clear that many of these companies also enter the acceleration phase of their existence (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Typical course of market development: Introduction, Growth, Flourishing and Decline.

The expected value of the shares of these companies which are in the acceleration phase of their existence increases enormously. This is the reason why shares in the acceleration phase of a revolution become very expensive.

The share price / income ratio of shares increased enormously between 1920 – 1930 (the acceleration phase of the second revolution) and between 1990 – 2000 (the acceleration phase of the third revolution). In acceleration phase of a revolution there will always be a stock market boom (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Two industrial revolutions: share price /income ratio

Share price /income ratio during a stabilization phase of a industrial revolution will decrease; The companies whose shares constituted the Dow also continued into the stabilization and degeneration phase (Figure 6).

4 WILL HISTORY REPEAT ITSELF?

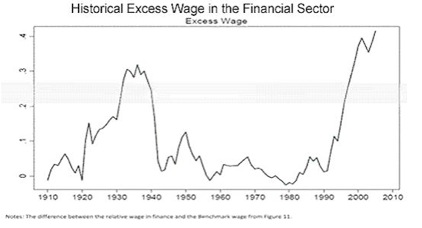

Calculating share indexes as described above and showing indexes in historical graphs is a useful way to show which phase the industrial revolution is in. Especially financial institutions play an important role during an industrial revolution. The graphs showing the wages paid in the financial sector therefore shows the same S curve as both revolutions.

Figure 7. Historical excess wage in the financial sector

The third industrial revolution is clearly in the saturation and degeneration phase. This phase can be recognized by the saturation of the market and the increasing competition. Only the strongest companies can withstand the competition or take over their competitors (like for example the take-overs by Oracle and Microsoft in the past few years). The information technology world has not seen any significant technical changes recently, despite what the American marketing machine wants us to believe.

Investors get euphoric when hearing about mergers and take overs. Actually, these mergers and take overs are indications of the converging processes at the end of a transition. When looked at objectively each merger or take over is a loss of economic activity. This becomes painfully clear when we have a look at the unemployment rates of some countries.

New industrial revolutions come about because of new ideas, inventions and discoveries, so new knowledge and insight. Here too we have reached a point of saturation. There will be fewer companies in the take-off or acceleration phase to replace the companies in the index shares sets that have reached the stabilization or degeneration phase.

Humanity is being confronted with the same problems as those at the end of the second industrial revolution such as decreasing stock exchange rates, highly increasing unemployment, towering debts of companies and governments and bad financial positions of banks.

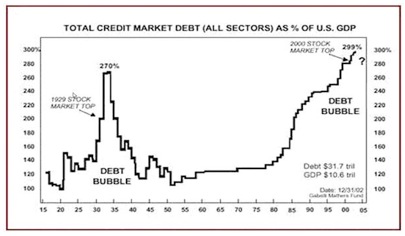

Figure 8. Two most recent revolutions: US market debt

Transitions are initiated by inventions and discoveries, new knowledge of mankind. New knowledge influences the other four components in a society. At the moment there are few new inventions or discoveries. So the chance of a new industrial revolution is not very high.

History has shown that five pillars are indispensable for a stable society.

Figure 9. The five pillars for a stable society: Food, Security, Health, Prosperity, Knowledge.

At the end of every transition the pillar Prosperity is threatened. We have seen this effect after every industrial revolution. The pillar Prosperity of a society is about to fall again. History has shown that the fall of the pillar Prosperity always results in a revolution. Because of the high level of unemployment after the second industrial revolution many societies initiated a new transition, the creation of a war economy. This type of economy flourished especially in the period 1940 – 1945.

Now, societies will have to make a choice for a new transition to be started.

Without knowledge of the past there is no future.

It is very clear where we are headed … to fascism. There is not only a breakdown in the economic model, we are facing peak oil. Since 2005 world oil production has been on a plateau. The only reason oil production hasn’t declined is frantic fracking and the “modification” of the definition of what constitutes “oil”.

Oil constitutes 95% of our transportation energy which also includes farming. The recent unrest in the world including the “Arab Spring” was precipitated by run ups in the cost of food and fuel. When you are living on one or two dollars a day any increases are life threatening and the increases in food and fuel have been substantial.

The damning fact is that the world can not maintain the complexity of its social and economic institutions with ever more expensive energy let alone less and less energy. One can look at the entire thrust of US domestic and foreign policy as preparing for this eventuality. The “game plan” has been to lower oil demand at home and abroad.

At home this took the form of causing and bursting the housing bubble to enrich the elites at the expense of all other classes. The Fed through its programs has fattened the already wealthy while decimating the middle class. Abroad US policy has been destabilization of economic activity through both economic and war on the Middle East , Africa and South America.

It looks as if even larger wars, economic and military, will be instigated and engaged as the US economy slides into yet another economic downturn. Certainly the efforts of China, Russia and other countries to escape the “dollar monopoly” will precipitate an effort by the US to “tank” the world economy to fend off any and all attempts at sidelining the dollar hegemony.

Exactly, energy use or consumption is paramount to the well being of any species. I feel that figure nine should replace food with energy (food and fuel) and should weight this category most heavily since it influences the others absolutely. There is a direct correlation between the explosive growth of the last 200 years and the use of energy dense fuel sources. On the political end, I feel the United States is already a mutation of the old fascist political structures. Though I’ve surmised that fascism is a political model that has existed in one form or another for thousands of years. We have just recently given it its current moniker. Fascism and all its ancestors are structures that seek to maintain their present order of power and privilege (they are reactionary), and they are inherently irrational because of their inflexibility. Therefore, fascism inevitably leads to catastrophe. My hope is that common folk take up the banner of class war and fight for our collective mind. It will save our ecosystem and it will save our entire species. Contrary to the oft repeated trope that underclass rebellions are just stirring an unnecessary class war, the war was declared eons ago by the fetishists of power and privilege, most people (including the powerful and privileged) are just unaware. The rich are ultimately as much a victim in this war as the underclass since we are all destroying our home.

Nice curve – taken from the “flies-in-the-bottle propagation” of a biology course. Economics mimics the same inception-growth-stabilization curve. But much of the art depends upon where one designates “inception” and when “stabilization”.

The Agricultural Age and Industrial overlapped in the middle of the 19th century with the advent of energy producing steam engines, later harnessed into alternating-current electricity to drive machines of all types. The Industrial Age is coming to its graceful end and has begun to do so ever since WW2 in which was bred the Information Age that has finally taken hold by pervading our economy – particularly via its latest development, the Internet.

We have thus transited the Industrial Age in to the Information Age, though that transition has not taken hold in many mentalities. Why? Because some ideas are harder to give up than others.

Like the one opining that a pioneer-derived Individualist Society must make way to Collectivist Society since there are no more lands to venture forth to pioneer. The entire Agricultural Age was one in which both farming and mineral extraction were prime industries, for which explorers sailed around the world seeking their riches. Moreover, we should be examining why our Individualist Culture is still predominant in a world where Collectivist

Our explorers are now Internet Nerds. Uh, excuse me, Internet Development Pioneers.

Most importantly, I submit, is the fact that obtaining the skills necessary to participate fully in the Information Age requires more brain-work than brawn-work. And for this, women have finally achieved equality in potential with men. Brain-work, in the Information Age, will be far more remunerative than brawn-work in terms of numbers employed.

The fact that we have transited, in terms of GDP, into a services-dominated economy simply proves that fact. So, we should be striving to assure that our educational systems allow as many young-adults to graduate from secondary- to tertiary-education levels as is humanly possible. It is in the latter that they will likely obtain the credentials to pursue a truly remunerative career.

Tertiary-education (vocational, college or university) graduates earning a diploma whilst accumulating an average $28K-debt is not exactly the sort of inducement that seems most conducive to that above-stated end …

Future History:

The third industrial revolution ended as the Age of Fraud began, starting with the decoupling of all currencies from gold by 1971. During the Age of Fraud, the wealth created by the second industrial revolution was siphoned off into the bank accounts of a small minority and the politicians they supported.

The Age of Fraud ended when the Information Age became the Disinformation Age, as the former middle class were convinced by the media that their newfound poverty was the natural order of things and that no other economic system was possible. Those who questioned the political and economic system were marginalized or met with a violent end.

The Disinformation Age ended in the worldwide energy crisis and famine of 2025.

To begin with, I don’t buy the five pillars because he leaves out the one essential one–mythological framework. My term encompasses a common narrative, common morality and so on.

I’m not sure I buy Gromman’s historical analysis either but let that rest–his main point, however, is apt as far as it goes. The chief feature of our current historical moment is we have reached the limit of the current phase of capitalism–but it has very little to do with technology or industrial efficiency. We are entering the end of an era and the clumsy start of another. The technology is available to fuel this new revolution but is being actively suppressed by reactionary political forces dominated by large corporations, i.e., the issues we face are not economic or technological but political. The revolution in industry and technology will explode to the degree corporate forces can be either circumscribed (more likely) or actively removed from their seats of power through social movements.

The history is to be suspected as you hint. I agree Banger, but the groundswell is the fascism of common sense, rather than re-organisation on good sense. I can remember a 1974 article (67 pages plus) in Harvard Legal Review on the collapse of the legal-commercial paradigm, which drew on Imre Lakatos’ notions of research programmes in science. We had people standing on democratic foreign policy tickets in the 1920s, Critical Theory has long made these points. What’s surely lacking in this article is the history in which we have chosen irrationality, the very base of charismatic leadership that relies on cronyism and booty (Max Weber did not save us from the Nazis).

Much social theory is utterly corrupted in practice. Read Gramsci (left union man) and you find Thatcher-Reagan policies, but sweeping away hegemonic resistances like trade unions, legal aid, welfare and freedom to organise against TINA. Your spiritual-myth dimension feels a lot like Habermas’ ‘communicative rationality’, though he’s hoping Reason will prevail rather than “magic” (I prefer magic, but we’d have to demystify what we mean). Godwin, writing 200 years ago:

“Politics will be displaced by an enlarged personal morality as truth conquers error and mind subordinates matter. In this development the rigorous exercise of private judgement, and its candid expression in public discussion, plays a central role,” – didn’t happen.

I only use “magic” as a label here. Yet we have just seen a demos larger than USUKEU vote for a dark side of it. And surely we think people would vote for a new green model if properly informed? Instead, we seem to live believing giving the rich all our money and continuing a system that hasn’t worked for centuries through an invisible hand, rather than organising ourselves for the direct solution.

Economics reminds me of a board room debate discussing making better typewriters in a typewriter factory after the advent of the wordprocessor. The Levellers, who fought with Cromwell, made no headway with him on argument. He controlled the army. We need some practical magic.

I enjoyed your comment–I really like the way you think. I think the whole magic vs. logic may be one of the more interesting issues we are facing. Western man seemed to think, after the end of the Thirty Years’ war that reason would usher in a new Golden Age but reason like magic has a dark side and that wasn’t appreciated.

Our missing ingredient in many discussions is an appreciation of the heart. I’ve seen heart displayed by atheists, religious fundamentalists, new-agers, peaceniks, soldiers, gang-bangers, cops and I’ve also encountered cruelty from those same groups. The path of the heart is, in my view, the sine qua non of any viable future–in fact, I believe the “magic” of this historical moment is that the situation seems cunningly devised by some higher intelligence to elicit a collective response that comes from the heart.

THE TITANIC AS METAPHOR

There is nothing new under the sun in what has happened during the Toxic Waste Mess that, in the fall of 2008, spawned the Great Recession. (From which far too many around the world are still have yet to see the light at the end of the tunnel.)

We generate classic market-frenzy induced bubbles – just like the last one (pick any historical date) and just like the next one. Because mankind, blinded by its own avarice, is unable to adopt and maintain a Moral Imperative. We have no ethical backbone – that is, sense of Social Justice as a communal norm.

We are all on the same economic boat, but – like the Titanic – after striking the iceberg, only a select few will make it into the lifeboats.

‘The beginning of the end of this revolution was in 1845 when Friedrich Engels, son of a German textile baron, described the living conditions of the English working class in “The condition of the working class in England“.’

Well! I’ll go t’th’end of our street! A book called “The condition of the working class in Britain” about – er – early smirks – the living conditions of the working class in Britain. Who’d of thought that!

Will this article improve with a few graphs? Nope (see Lafayette above). The guy has noticed the stock market is a pyramid scheme and that we need to pat attention to real history or have no future.

The Indians have just voted for a Hindu fascist they haven’t managed to put on trial for mass murder. Here UKIP’s spokesman for small business and token ‘we ain’t racist’ person, has been nicked for using illegal immigrants in his Manchester Indian restaurant. He was a main plank in their anti-immigration policy. Next week, we vote across Europe, against European fellowship, for a bunch of pretty vile fascists, valuing democracy so much most of us will stay at home. Serious mass murder is likely in India, leading to confrontation between two nuclear powers. The US, once beacon of hope, has Fox News.

Like we need S-curves to tell us we live in a deeply irrational mess? Vote Groaf-Oaf, you know it makes no sense.

Three questions:

1) In the early 1900s, did Teddy Roosevelt’s trust busting prolong the 2nd revolution in America?

2) Did the creation of the Fed hasten the end of that same revolution?

3) What role does overpopulation play in all this? If I remember correctly the Black Death created a labour shortage which allowed workers to demand higher wages for the first time. Perhaps marking the beginning of the end of Medieval Europe’s feudal system. Today, when I set aside my bias against those in charge, I can’t help but wonder if our biggest problem is simply too many people. I guess any dummy will naturally jump to that conclusion when he sees massive unemployment – like during the Great Depression. Was it Keynesian economics that brought on the 3rd revolution or was it millions of people being killed off during WW2?

I’d have to write a book of answers on that Eoin. In short, I agree the questioning approach. We avoid the tough questions – e.g.

Mass killings with nuclear weapons is an abortion (true)

Ban the bomb

Which leaves them with the bomb?

We are burning and poisoning the planet (true)

We’ll go green then

Which leaves them out-competing us, building better armies and still screwing the planet?

I teach history but I’m not an economic historian so I can’t claim any particular expertise here. But what the hell it’s only a blog so I’ll spout off anyways.

I’ve been dutifully following the accepted outlines of early modern and modern economic historiography by teaching the First and Second Industrial Revolutions, using roughly the same time frames that Grommen uses (1760-1830 for IR#1, 1870-1930 for IR#2). But I’ve become increasingly skeptical about the validity of this sort of periodization, especially since it’s difficult to define it in consistent terms. Meaning that using technological change (iron in IR#1, steel in IR#2) as a definition tends to elide the elements of continuity (longue duree etc.). In fact, using technological signposts as convenient ways of periodizing economic change begins to look pretty unconvincing under closer scrutiny. What could be more convincing–and insightful–is to use clusters of institutional change instead. Examples would be: monopoly overseas trading companies/stock exchanges (1600), or limited liability corporations/industrial investment banking (1850). This kind of periodization has its pitfalls too–we can find precedents for overseas companies and share-trading as far back as medieval Italy. But what we’re really discussing is the issue of what happens to capital over long periods of time, and one could make a strong case for arguing that in this context institutions are a lot more important than machines.

Actually his history is taken from some basic economic history text. Good points Succo. Egalitarian but murderous hunter-gatherers, slave-class farming and broken backs, piracy and protection rackets (empire), fossil fuel burning and now robot heaven with a slave work ethic as we prepare the planet for aliens who like things hot.

What percentage of the population must be supported by the pillar of prosperity to consider it still standing? If the [delusional] well being of the elite ruling class does not seem threatened, what percentage of economists will perceive the danger of collapse?

Interesting if a bit overblown. Yes, finance is a scam and financial markets are corrupt and corrupting. Yes, society needs to limit the behaviors of financiers to minimize the damage they do to the society as a whole. There’s ample documentation on the implications of that kind of failure. No, this time is not different.

His three Industrial Revolutions attempted to eliminate human labor from production, (to a lesser extent) from distribution, and recently from clerical, administrative, coordinative activities. One observation is that Finance, being almost entirely clerical, has recently been de-humanized and we rely on the ethics of machines that demonstrably have no ethics built-in. The removal of any sense of personal responsibility in the financial markets is amplified by Neo-Liberal dog-eat-dog Individualism (Ms. Rosenbaum would be pleased with her posthumous success). However, the fourth such “revolution” will be an automated attack on “point of delivery” labor costs with robots and drones and will be widely touted as another great leap forward. The intriguing question is what to do with all the people made redundant by all these innovations? It is a problem our brilliant social scientists would like us to ignore. They demonstrably have no answers. Their hard science and technology buddies are busy convincing Capital to aggravate the problem.

Couple that with the decreasing return on technological innovation in regards to Malthus’s original observation, with various resource depletion scenarios, and with the one growth-industry that doesn’t contribute to overall societal well-being (population). Depressing, no?

I don’t buy this index analysis at all. It’s not shares that matter; it’s the market value of the shares. The index is just a normalized value for the weighted total market value of companies in the index. And of course the corporations included in the index changes constantly and you do need to track splits etc. When you drop one business and substitute another you maintain the continuity of the index and correct weighting by adding the number of shares of the substitute to maintain a constant value of the index.

You are missing his argument, which he went through longer form in his Dow post. With the Dow, companies in sunset industries are the ones thrown out and ones in rising industries are added. This creates as strong growth bias in the index.

And it’s a mistake to brush away how the index is computed. Any one who designs indexes will tell you any method of index computation creates biases, some more than others.

Poor Wim just doesn’t get it about indexes. Both the Dow Industrials and the S&P 500 are large-cap indices. By definition, their constituents change as growing companies enter the top ranks, while declining companies either get bought or simply fade back into small caps. For instance, Intel (which went public in 1971) and Microsoft (IPO’d in 1986) by 1999 had become large-caps, and entered the DJIA.

‘The fact that in the 1990-ies many shares were split is probably the cause of the exponential growth of the Dow Jones index. At the moment the Dow is at 13207 points. If we used the 1985 formula it would be at 1760 points.’

It would, but then it would understate the return received by an investor who actually held the 30 constituents. When shares are split 2:1, the investor ends up with twice as many shares at half the price, and her account value is unchanged. Failing to adjust the Dow divisor for splits would produce spurious step-function drops in the index every time a split occurred, but those drops would not occur in a brokerage account holding the 30 individual shares.

Don’t believe me? Then please explain how the DIA (Dow Diamonds ETF) has managed to track (minus annual expenses) the Dow Industrial index since 1998, with only minor deviations. If Wim thinks the DJIA is a pyramid scheme, why isn’t he buying the DIAs?

As they say in Japan, AMAJAA! (amateur!)

See my comment above:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2014/05/problems-associated-with-end-of-third-industrial-revolution.html#comment-2140686

Pyramids leave unsaleable junk in people’s garages. What was needed in the analysis is why the stock market in any form represents growth. One can go to the doctor’s with a growth.

David Blitzer (who actually does indexing for a living) addresses a point that Wim Grommit just can’t wrap his head around:

Changes to the S&P 500, the Dow and other indices report shifts in the corporate world rather than causing them. However, there is more going on here than the speed of innovation and technology. About two-thirds of all exits from the S&P 500 are caused by M&A; and, more often than not, both the acquirer and the target are in the S&P 500.

When a company is acquired, it may drop off the index but its activities, products, revenues and (hopefully) profits remain – and stay in the index if the acquirer is in the index.

http://www.indexologyblog.com/2013/09/13/companies-dying-faster/

Interesting, if the company stays in the index after an M&A then you need to add a company to keep it at 500. But to keep the value (index) constant you have to adjust the shares of the 499 other companies in the index to weight them properly. That sounds expensive

As I said above, he went through his argument on the Dow in a previous post, including naming the companies that were added and exited. Your discussion of the S&P is a straw man. While more savvy types pay more attention to broader indexes, the Dow is the one that is touted most in the news to the great unwashed public.

Yes, I realize he was focusing on the DOW but in section 3.1 he references the S&P500 and implies that other indices are constructed similar to the dow. I agree the dow is a particularly bad index and I try avoid its heavily broadcast influence. I invest mostly in a total market ETF index fund with very low fees and low churn and which I believe is a good indicator of the total market. The article irritated me because it seemed to implicate all indices and hence attempts at passive investment as futile.

My belief is that the purpose of a stock market index is that it is intended to be an indicator, over a period of time, of the performance of a market, subset of a market or perhaps some aspect of a particular market. Utilizing that definition, and after reading this and last week’s related article I would have difficulty drawing long term conclusions using the DJIA as an accurate performance indicator. As a day to day or short term indicator perhaps, but only during periods in which there are no changes in the Dow component members. Unfortunately if the author’s assertions are correct, it seems the DJIA suffers from a clear selection and retention bias of component members.

To draw an analogy, we could make the education problem in the US disappear by simply changing the way in which the students, whose performance is being monitored, are selected for inclusion in future studies. I suggest future studies of student performance should include only students whose historical test performance is in the 90th percentile or above and that miss no more than 2 days of school per year. Students initially selected to be included, but who fail to maintain the place at 90% or above, or miss more than 2 days per year, would be removed and replaced by other students, not yet selected, who do meet the performance standards.

Because of the lack of historical performance records in early years (E.g. K through 2nd grade), there would most likely be more student component churn. But it will also increase the likelihood of guaranteed increases in student performance averages as the students’ progress from the early grades to higher grades. We could literally take control of student performance results and eliminate any chance of those pesky low performance results

Now clearly the DJIA is not computed with that level of manipulation. But it does seem to me that from what the author shows, the inherent bias in its computation clearly takes us in that direction.

“Thanks to the machine[,] faster and cheaper production was possible and labor remained cheap.”

By making labor redundant, labor-saving technological advances (automation) may lead to weakened consumer demand, which can result in a depression. Keynesian economics advocated replacing weakened consumer spending with government spending to support a weakened economy. Since the 1980s, Neoliberalism, the now-dominant post-modern economic paradigm, has replaced Keynesian theory as the new economic reality.

There appears to be a roughly 5000-year-long lacuna in the author’s narrative, from 3000 BC to roughly 1800. Are we to believe that little of note with regard to the development of technology and industry occurred during that span, which included both the bronze and iron ages as well as the European renaissance, the building of the great pyramids, the invention/development of writing, mathematics and predictive astronomy, rise of large-scale land-and-seafaring for exploration, trade and warfare? Really?

Regarding the alleged wonders of humanity being relieved from both physical and mental tedium, I think we may have well overshot the happy medium on both those marks, as embodied by the developed-world obesity epidemic and addictive disorders characterized by slavish dependency on the EZ-instant gratification offered by e-media. On that theme, an exchange from one of my favorite cheesy-but-fun 50/60s SciFi movies, The Phantom Planet (1961):

Sessom: It’s true that our technology may be further advanced than yours, but then strange things happened.

Capt. Frank Chapman: What was that?

Sessom: We let our machines do all our work. People on Rheton became completely free of all labor, practically of all responsibility. Our people became soft and lazy. They did not know how to cope with their free time. They started to fight among themselves.

Capt. Frank Chapman: That’s very interesting. Many people on Earth are beginning to face the same problem: too much free time, too little work.

Capt. Frank Chapman: A problem not at all unique in the history of the universe.