By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Readers wanted to hear more about activism in the great State of Maine, so I thought I’d oblige with some material about globalization and the horrible (and still proposed) “East-West Corridor.” (I should caveat by saying that although I’ve been peripherally involved in fighting a humongous landfill, all the other fights up here require a car — Maine really is a big state — and I don’t drive. Even worse, a lot of what I “know” about these fights has come from discussion, and there’s plenty that never appears in the papers, so I may not be able to uphold my usual standard of linky goodness.)

We read a lot about water wars out West, but there aren’t any water wars in Maine, unless you count Nestlé’s Poland Springs privatizing our water to sell it out of state, or the leachate from landfills with liners waiting to fail, or the dams, which, give credit, we’re getting rid of. Anyhow, Maine is blessed with water and Maine is blessed with land, and that gives rise to the feeling many Mainers north of Augusta have that “when the trucks stop,” Maine will be able to survive, and perhaps even prosper, up here on the margins because we’ll be able to feed ourselves on what we can grow, or catch, or hunt, or forage. (Maine was once “the breadbasket of New England,” although, to be fair, others states also made the same claim.)

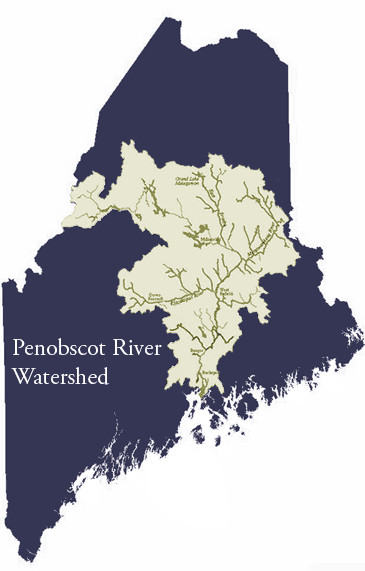

All living creatures need water. So if we are to grow wheat, or catch salmon, or hunt deer, or forage for fiddleheads, we need water. That makes the Penobscot River, and its watershed, very important (and the more apocalyptic your views of climate change and its knock-on effects for things like, oh, trucks, the more important the Penobscot becomes). Here’s a small map of the Penobscot Watershed (best I could find, sorry):

Figure 1: The Penobscot Watershed

The Penobscot River Restoration Trust writes:

New England’s second largest river system, the Penobscot drains an area of 8,570 square miles. Its West Branch rises near Penobscot Lake on the Maine/Quebec border; the East Branch Pond near the headwaters of the Allagash River. The main stem empties into Penobscot Bay near the town of Bucksport. The landscape of the watershed includes Maine’s highest peak, Mt. Katahdin, rolling hills and extensive bogs, marshes and wooded swamps.

The Penobscot is best known for its large historic salmon run (50,000 or more adults) and its much smaller contemporary run, which is the largest Atlantic salmon run remaining in the United States (1,000-4,000 adults in recent decades).

Water quality in the Penobscot River has greatly improved during the last 30 years due to the reduction in industrial pollution required by the Clean Water Act. Communities across Maine already have turned toward these cleaner waters, revitalizing their riverfronts. The return of the Penobscot sea-run fishery and free-flowing river sections will provide opportunities to realize the river’s full potential, including revival of cultural and social fishing traditions.

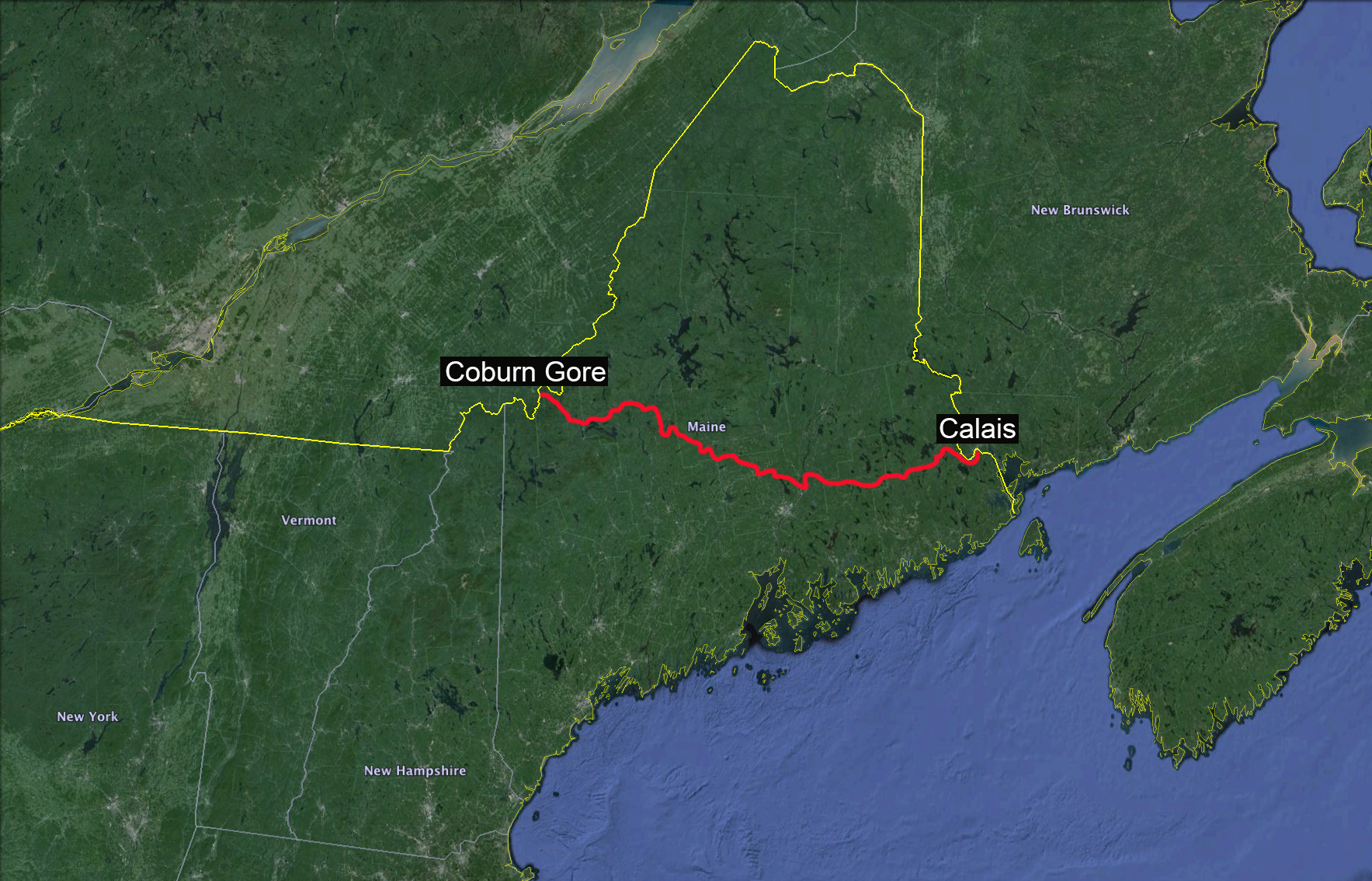

Now let’s turn our attention to a seemingly different project, the proposed East-West Corridor. Let’s start with another map; the red line across the state is the Corridor:

Figure 2: The East-West Corridor

Figure 2 is useful, for starters, because it gives a “birds eye view” of the State, where the 0.01% who fly over it in their executive jets are the birds. See all that green space? There’s nothing there— to them. Figure 2 also gives a rough idea of the route the Corridor will take, from the border crossing into Canada in the east at Calais, to the border crossing in the west at Corburn-Gore.

The East-West Corridor is being sold, as you might imagine, because “groaf/jawbz,” but that’s ludicrous. Only six exits are planned, so that’s six 7-11 clerks and a Tim Horton’s server or three. Hardly the stuff of economic miracles, and anyhow, if highways brought jobs, we’d be rolling in the dough after they built US95. So something else is on the agenda, but what? We ask ourselves, who’s pushing these? Two people: First, Peter Vigue, CEO of Maine’s (globalized) construction company, Cianbro. And second, the Irving family (Canada’s third-ranking squillionaires), on our side of the border a (globalized) forest products company, and on the Canadian side, a (globalized) energy company. So, Cianbro gets the construction work, and the Irvings get to do what forest and energy firms do best: Extract resources.

And which of Maine’s non-renewable resources — forest products being renewable — might the Irvings wish to extract over the Corridor built by Cianbro?

- Possibly water, just like Nestlé;

- Possibly fracking water, since although Maine is blessed by having no hydrocarbons, Canada, both to east and west, has oil shale;

- Maine also has plenty of empty space for fracking injection wells;

- Possibly gold from an open pit mine on Bald Mountain up in the County;

- Probably gravel from the eskers that line the route

And then there are the uses to which the Corridor itself might be put. (Here I should say that although the Corridor was originally marketed as a road that public could use, it’s never been any such thing; it’s really just a real estate speculation. Since the Corridor will be privatized, the developers can do whatever they want within their property lines (subjected, granted, to a compliant permitting process.) That red line on the map could be a road that makes it easy for Canadian truckers to cross the state, instead of going around it, and the road for Irving to ship forest products, water, and gold out of start, but it could also represent:

- Pipelines of all sorts, with perhaps one connecting the Enbridge pipeline to Irving’s Canadian refineries;

- Rail, for tank cars for the same purpose;

- A power line route if Maine’s wind projects ever get big enough;

- The route to bring in out-of-state trash to dump in Maine’s landfills.

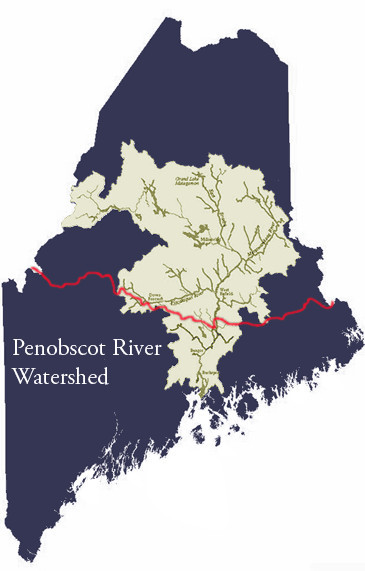

Of course, all the by-products from construction, mining, fracking, and truck traffic, not to mention oil spills, whether from the pipelines or rail, have to go somewhere; the earth is round, after all. But where? Figure 3 gives the answer:

Figure 3: The Penobscot Watershed and the East West Highway

That’s right! All that crap is going to go right into the Penobscot Watershed, because the East-West Corridor cuts right through the heart of it! Maria Girouard of the Penobscot Nation explains the insanity:

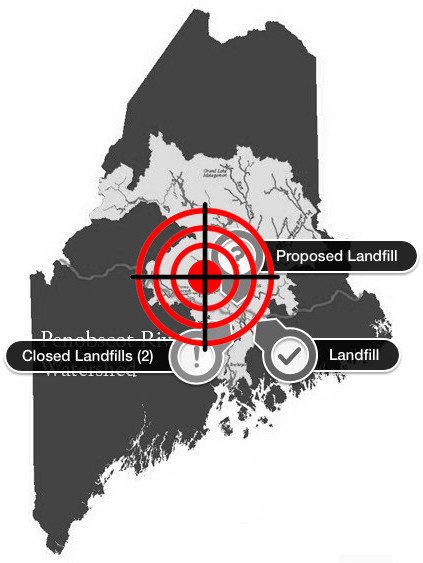

Let me expand on that last bullet point about out-of-state trash, because it’s near and dear to my heart.

Figure 4: The East-West Highway and Landfills

In a thirty or forty mile radius around Bangor, there are two closed landfills, one of the largest landfills in New England, Juniper Ridge (named “Mount Baldacci,” for the Democratic governor whose scheme it was), and another proposed landfill. It has not escaped our notice that Juniper Ridge and the proposed new landfill are both very close to an exit off the East-West Highway. And we all know that Europe likes to dump its trash on Africa, so why not send it in containers across the Atlantic, and dump it in Maine instead? Why, after all, should one do business with third-world thugs, instead of upstanding North Americans?

At this point — with European trash dumped in Maine — we’ve entered a truly globalized context, but that’s been the context of the East-West Corridor all along. Water for Life organizer Chris Buchanan writes:

But what do existing and pending free trade agreements have to do with the East-West Corridor proposal? A great deal. In sum, the East-West Corridor is the enabling infrastructure for increasing free trade in the Northeast United States and for all of Canada.

As a privately owned and operated consolidated utility corridor up to 2000 feet in width from Calais to Coburn Gore5, the corridor would profit its investors most by maximizing uses. Therefore, we could expect not only a noisy toll highway with different regulations than public roads6, but also a tar sands pipeline, natural gas pipeline, crude oil pipeline, communication cables, DC electric cables, bulk water lines, and more.

Effectively, we’re looking at a privately owned,controlled, and secured Super-Corridor, permanently dividing land that has been accessible to people and animals for time immemorial, from foreign border to foreign border, designed to benefit transnational corporations involved in various resource extraction processes that are major players in the global economy. By nature, it is a Free Trade Corridor, envisioned to maximize movement of globally traded products to and from Canadian ports.

Figure 5: Maine in the Crosshairs

All of which explains why we, up here in the sticks, feel just a little bit like this:

Amazingly, so far Mainers have been able to slow one landfill, have swiftly organized against the planned one, and have fought Cianbro and the Irvings to a standstill on the Corridor. Here, however, is the key point: 90% of the land in the Penobscot Watershed is privately owned, and most of its owned by forest product companies (i.e., the Irvings). Tactically, that means that all that the Corridor Boosters really have to do is put together land they already own with a few small parcels to complete the route. Strategically, that means that the Penobscot Watershed cannot be treated as the Common Pool Resource that is is. So far, the Irving and Cianbro have failed. And if they sense defeat, who will they sue for lost profits under international trade agreements? Some embattled farmers and a few Indians in the Maine woods? Ha.

So, stay tuned!

NOTE I wrote up some lessons learned on landfill activism here.