Philip Pilkington is a London-based economist and member of the Political Economy Research Group at Kingston University. Originally published at his website, Fixing the Economists

Tom Palley has written a blog post politely requesting that Paul Krugman might give a bit of recognition to non-mainstream contributors to economics. It would be nice to see this happen but I doubt that it will (although Palley is getting a bit of blog play out of it which is nice). Anyway, I note that in the post he links to a discussion him and Krugman had regarding the Phillips Curve. Before I get to the arguments put forward here let us examine the Phillips Curve in some detail.

The curve was an empirical relationship that the economist William Phillips found in 1958. Phillips noted that movements in wages and unemployment were negatively correlated in the UK between 1913 and 1948. The neo-Keynesians then picked up on this and argued that there would be a negative relationship between unemployment and inflation. They figured that wages were the key driver of inflation and that, since unemployment was the key driver of wages, then it must be the level of unemployment that must drive inflation.

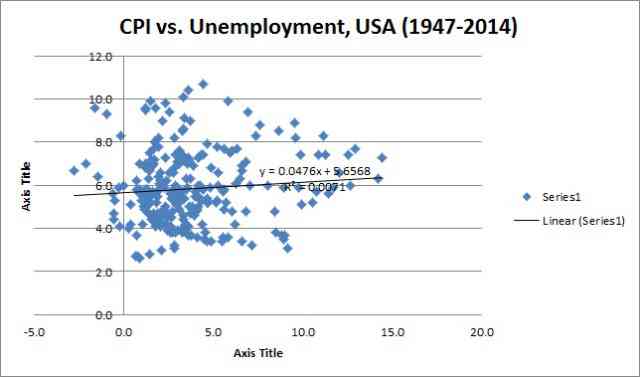

It was quite a heroic leap by the profession to formalise a General Law from a total of 35 observations, but formalise they did. After all, it was a neat theory and economics at this time was trying to emulate the hard sciences. Well, the Phillips Curve didn’t work so well over the next half century. Here is a scatterplot diagram with a fitted curve showing the relationship between unemployment and wages in the USA from 1947-2014 (all data from FRED).

Now, if we saw a negative correlation — that is, if inflation rose as unemployment fell — we would expect to see a strong downward-sloping relationship. Actually the relationship is slightly upward-sloping meaning that inflation more so increased when unemployment increased. We also see a very low R-squared which can also be seen by how far off the line the various datapoints are. In English: there is no firm relationship here and the extremely weak relationship we do find runs in the opposite direction to what the Phillips Curve would predict.

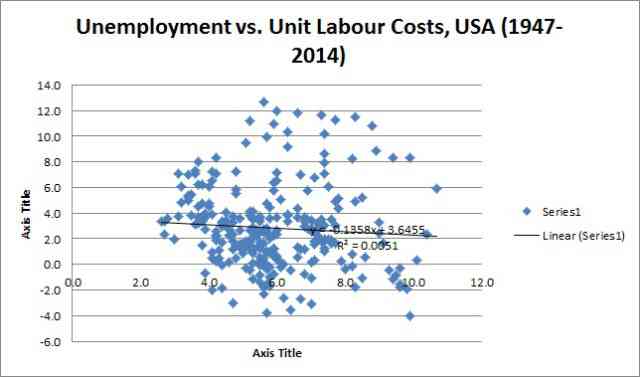

So much for Phillips Curve theory. But what about the relationship between unemployment and wages? After all, this is what Phillips himself tried to show. It was the neo-Keynesians that came after him that tried to generalise based on his observations.

Well, here we at least see a somewhat negative relationship, albeit extremely weak. But we see an even lower R-squared. Basically it seems that the relationship between wages and unemployment in this period is pretty chaotic. In English: again, this is bunk; the sought after relationship does not exist.

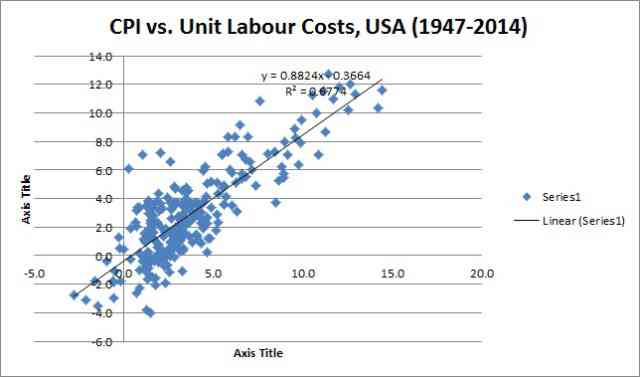

Is this all hopeless then? Can we say nothing about inflation at all? No, all is not lost. There is one relationship that does hold firm: namely, that between wages and inflation.

Ah, there we go! There is a nice strong relationship between wages and inflation. When wages rise, inflation tends to rise. This, however, does raise the question of causality. After all, it could be that rising inflation leads to rising wages. Or it could mean the other way around. Frankly, we cannot say.

Indeed, I would be very hesitant to make any generalisations here. Sometimes inflations are wage-led. But sometimes wages rise in response to other sources of inflation. Every inflation must be studied in its particularity. Trying to generalise abstract laws that mimic laws in engineering or hard sciences is just stupid and will just lead up a blind alley.

This brings me back to Palley’s post. He notes that the mainstream have basically tried to solve this problem by incorporating expectations. If workers expect inflation they will bid up wages and so on. This is obvious nonsense and will not lead anywhere at all. If, for example, workers were heavily unionised and radicals got control over the unions we could easily imagine them just bidding up wages no matter what they thought inflation might be. They would just be doing so in order to get more of the economic pie. It is not like this has never happened before in history (*cough*, Allende in Chile, *cough*).

Palley is more realistic in this regard when he writes:

In my view, the real issue is the extent to which inflation expectations are incorporated into wage behavior. Workers may have absolutely correct expectations of inflation but not incorporate them into nominal wage demands because of job fears. (My Emphasis)

Here Palley hints at the fact that there is an aspect of social power to the bargaining process. Hence, if workers fear getting fired they might not try to bid up their wages. But once you open this box it is pretty hard to close. The power dynamics of worker bargaining are enormously complex and require historical and institutional nuance. Palley appears to instead fall back on the idea that bargaining power depends on unemployment — that is, that workers will bid up wages when there is low unemployment. But, as we have seen above, this position does not have empirical support.

In reality power dynamics are complicated and need to be studied in and of themselves. There are also many different types of inflation, as John Harvey has noted elsewhere in an excellent piece. In my forthcoming book I note four key types of inflation. These are as follows:

- Demand-pull inflation.

- Cost-push inflation.

- Speculative inflation.

- Exchange-rate inflation.

In laying out a Phillips Curve, or any other contraption, we are likely to only capture one type of inflation. Indeed, in the case of the Phillips Curve we only capture one sub-type of one type of inflation — namely, a sub-type of cost-push inflation (wage inflation). This does not lead to cogent thought. Given that Palley is in a dialogue with Krugman it might be worth pointing out that the latter has extremely crude views on real-world inflation which I have noted before. In subordinating one’s thoughts to a contraption one always runs the risk of blocking out the real-world.

Why is it so controversial to make this point? Why do we have to try to form a single theory of inflation? Why is it that a theory is only valid when it has been laid down in black and white form in a model? After WWII the profession tried to formulate a General Law of inflation. It was a disaster. Why on earth would we want to try to do this again? If economists — especially Keynesians — have not yet grasped that history will melt their attempts at timeless construction, they learned nothing from the lessons of the 1970s.

But that comes back again and again to that old timey question: why does every aspect of economic theory need to be cast in terms of a model? Sometimes modelling clarifies thought, but sometimes it obfuscates it. Inflation is such a complex, historical phenomenon it is definitely one that is obfuscated by modelling. So, why the need for models? Frankly, I think it is on those that build them to justify this, not on me to engage in conjecture in criticising it.

The John Harvey link points nowhere in particular on Forbes. This is the likely intended target:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/johntharvey/2011/05/30/what-actually-causes-inflation/

“Why is it so controversial to make this point? Why do we have to try to form a single theory of inflation? Why is it that a theory is only valid when it has been laid down in black and white form in a model? After WWII the profession tried to formulate a General Law of inflation. It was a disaster. Why on earth would we want to try to do this again?”

Maybe because most economists in the last 3 decades are failed Mathematicians who cross over to Economics. Dealing with more than two variables is tough for them. Dealing with multiple variables and non-linear systems is a complete non-starter because they failed differential equations in school itself.

Maybe because if the world ever learns that what economics is trying to do is predict/model human behavior, people would immediately understand what quackery the profession is pursuing and they would lose all credibility immediately. We should not forget that Keynes himself disdained the use of Math which the Right Wing Morons of his time were actually using to cloud and fog their actual intentions of preventing the State from playing its role in the marketplace.

Even Philip is academic enough to not consider the big one. Which is fraudulent profiteering and financial pillage. And/or political profiteering. Same things. Totally synthetic “economic” means which create inflation. In addition to his 4: (demand pull; cost push; scarcity spec; and exchange rate or debt driven)… Competition seems to be an accepted negative factor which brings inflation down due to enhanced productivity, but alas productivity trashes the environment and eats up both resources and energy… causing life itself to be out of reach…and also reduces demand drastically because it sucks the last breath out of labor/wages… and so what’s an economist to do? Heaven forbid they should all ‘fess up that the whole dame thing is a fantasy. Except for cheap wine.

damn

All the modeling done by economists is part and parcel of the web of rationalizations necessary to support the bad behavior of the financial sector.

Selfish behavior that badly impacts the common man requires excuses.

Not just the bad behavior of the financial system players, but also of any corporate entity or captured regulator. Economics=Apologetics…at least as it is currently practiced.

Here’s my take on a more realistic way of viewing employer-employee relationships:

Labor Market as Ultimatum Game.

And I have to say something about Allende. Phil seems to imply that Chile’s economic woes during the last two years of the Allende administration were self-inflicted. Perhaps to some degree, but let us not forget:

Which makes it pretty difficult to tease out cause and effect and separate purely the economic results of policies from the political blow-back encouraged and funded by outside intelligence agencies.

As for the actual topic of this piece: yes, the Phillips curve is ridiculous, no surprise there. The surprising thing is that Krugman is still, I take it, defending the concept. But then again, Krugman believing nonsense isn’t really all that surprising.

“Making the economy scream” was a CIA weapon. It had no basis in economics or equality or environmentalism. It was as toxic as a nuclear weapon.

This is an important post. As Wray has emphasized stagflation is the cause of most US inflation rather than increased demand, so not related to Phillips curve. For inflation at less than full employment it depends on where the demand is generated. Inflation: too many speculators chasing too few commodities.

Podcast

Taibbi emphasizes this commodity speculation as an important aspect of inflation. He notes that starting in the early 1990s and accelerating from 2003-2008 speculators have overwhelmed the commodities markets which formerly was more restricted to hedge positions from people who were actual producers or consumers of these commodities.

Taibbi

So was dedication to the Phillips Curve the ideological justification for off-shoring all our manufacturing? So we could prevent “inflation”?

It does seem that it could be used in the war against wages. And in a broader sense as seeing unemployment as being useful rather than being seen as a failure to reduce the output gap.

It’s not the federal debt that will hinder our children and grandchildren but austerity which limits the production of useful items and their educational development. And reducing the various benefits of basic research.

Gar Alperovitz has a good discussion of the current success of various co-ops and worker owned projects which hang on to local jobs and provide for local demand.

Alperovitz

And Phillips used nominal wages not real wages… as pointed out eloquently by Anwar Shaikh long ago… so the neo-Keynesians made a fundamental error… but hey, they are not really neo-Keynesians… they do not even know the basics of the difference between uncertainty and risk… and rely on the ergodic axiom which Keynes explicitly rejected…

Should one invert the sequence of its fifth and seventh letters, as a dyslexic might easily do, the Phillips curve becomes …

PHILPIL’S CURVE

Take ownership, brother.

So, why the need for models?

Perhaps economists have faces for radio, and just want to look at something pretty, instead of in the mirror.

RE: Phillips Curve

Quack economics by self-serving quack plutocrats and bankers!

1. i don’ think there is so much a cause and effect between wages and inflation as there is a feedback cycle. Something like, workers push for higher wages, businesses see the extra spending power and ups their prices, workers go back to pushing for higher wages to regain that spending power, etc etc etc.

2. Trying to look for the original Phillips curve in such a wide amount of data is likely to be futile, given the changes in the labor market over the last decades. The curve may hold up in a closed system (single nation with protectionist tariffs). But thanks to globalization, it is anything but closed.

3. all this ignores consumer credit, the one big elephant in the room when talking inflation.

The Phillips curve fited the data in some circumstances – but not others. That we are still talking about ‘the Phillips curve’ is a tribute to the non-empirical basis of much of contemporary economics. There was excitement in the 1970’s when this fit the data. If the Phillips curve is valid , suppressing wage growth in the name of fighting inflation is easy to justify. The developed world, particularly austerity Europe , is still in this crusade.

Back in the 1960s modeling seemed to be a reasonable alternative to the dotrinal use of “laws” because models permitted tinkering so as to incorporate more and contradictory data. No insight was final. In the Phillips curve and even more notoriously the Laffer curve, we see models used independent of data and independent of tinkering to try to incorporate the contradictory details.

The big debate in economics today really is between orthodoxy and a continuing search for truth that extends beyond immediate historical contexts. The debate is whether economics can transcend the current system of capitalism and lend insights into other previous or even alternative systems of organizing the political economy and the patterns of economic activity (supply chains, etc.).

“dotrinal” –> “doctrinal”

Perhaps it can. We might call that discipline “history.”

Apply the conclusion [arrived at here] to all things, and your on the right track.

Phillip,

I recall now with this point of clarification what I thought was a problem with econ 101 as it was being taught to me in 1975. Namely, without reference to the a formal name, Phillips Curve, we were flatly told that you could manage the economy with a trade off between employment and inflation. You would need the right policy mix to get max employment with minimum inflation, because you could NOT HAVE HIGH UNEMPLOYMENT AND HIGH INFLATION AT THE SAME TIME. At which point I picked up the screaming headline from the NY Times and held the paper up as a prop: Inflation sky rocketing at same time unemployment rate climbs!!!!!!

Young and naive, I raised may hand to ask if that is so, then why are we today in the US of A experiencing the exact opposite of what you’re telling me is the science of economics that I need to understand and repeat back to you correctly in a test so I can get an A and go to law school? Why is there a contradiction to your claims by the events of American economic reality? Now, that was the question, without the subtext so explicit, but, I did not know I was not suppose to ask real questions in classes like that and expect real answers because I actually wanted to understand how the world worked. Now for the answer. In the midst of silence so complete you could have conducted acoustic experiments, the full prof and author of the text we used said: “That’s a good question and maybe someday you or someone else in this room will study economics and be the one to answer that question.”

So Phillip, I personally want to extend my thanks for getting a real answer to a question I asked so long ago only to be treated to among the first of many bullshit answers from authoritative profs. It didn’t make any sense then, and now, with you in depth discussion, I know why. And I know, once again, that I was not crazy in my youth and a really really smart kid. If only the kid knew then.