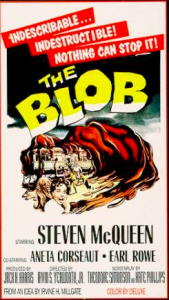

Lambert here: While NC is not a graphics-heavy site, perhaps a poster from the original “The Blob” (1958) would be a propos:

Inevitable! Indestructible! Nothing can stop it!

This post first ran on October 2, 2012

This is a review of the new book by former Senate staffer and super-lobbyist Jeff Connaughton, Payoff: Why Wall Street Always Wins. The review is written by Matt Stoller, who writes for Salon and has contributed to Politico, Alternet, Salon, The Nation and Reuters. You can reach him at stoller (at) gmail.com or follow him on Twitter at @matthewstoller

There’s a slate of important books coming out by reformers this year on what it was like to fight, and lose, for better policy during the financial reform fight. Neil Barofsky talked about facing the administration and Wall Street in Bailout, Sheila Bair has written about her experience at the FDIC, and now former Senate chief of staff for reform Senate Ted Kaufman, Jeff Connaughton, has provided his own memoir. Connaughton is not a rube, and doesn’t pretend to be shocked by DC corruption. His whole career is an anomaly, an idealist turned corporate super-lobbyist in the 1990s turned unlikely reformer in 2009. As such, he is uniquely positioned to describe how our political leaders, and which political leaders, think and act.

One anecdote in his new book The Payoff: Why Wall Street Always Wins really gets at when the failsafe mechanisms for our financial system were in the midst of collapsing. The crisis of 2008 was when the dam broke, but the actual structural weaknesses appeared long before, in the 1970s, and accelerated in the 1990s. Connaughton was a player in both the period of accelerating weakness, in the 1990s, and in the collapse itself.

Throughout the book, Connaughton shows how the system was corrupted by ensuring that only voices within the establishment were heard. For instance, in 1995, Connaughton was a lawyer in the White House, and he and his colleagues had persuaded Bill Clinton to stand up to Wall Street by vetoing the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. This bill would make it harder to prosecute securities fraud when CEOs made positive statements about their own company while selling company stock. It would undercut SEC Chair Arthur Levitt, who was furious at the way Congress leveraged its appropriations power to challenge his agency’s ability to protect the capital markets. More importantly, it was Bill Clinton’s most significant and last attempt to stand up to the power of big finance. Senator Chris Dodd and then White House deputy Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles were carrying water for Wall Street in an attempt to loosen the ability to commit securities fraud, but Connaughton had managed to work the White House levers to go around them and get to Clinton himself. After the meeting where Clinton was persuaded to oppose the bill, Clinton saw Connaughton standing alone in the White House hallway. The President went up him, and revealed his unease at what he was about to do.

“You think I’m doing the right thing, don’t you?”

“Absolutely, Mr. President. You can’t undercut the Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission on a question of securities fraud.”

“Yeah, that’s right. And Levitt is an Establishment figure, right?”

“Yes, Mr. President, that’s right.”

Clinton, even in opposition to big finance, cowered before the opinions of the establishment. Of course, the stamp of approval from Levitt wasn’t enough. Senator Chris Dodd went to work. First, Dodd killed a Clinton endorsed Senate amendment put forward by Paul Sarbanes designed to remedy the problem, forcing Clinton to veto the whole bill. Dodd then went for an override. Connaughton implies that Clinton put the word out that he wouldn’t really mind if the override succeeded, and with that, the political opposition to the bill collapsed. Even Ted Kennedy voted for Dodd’s bill. And so another brick in the wall that had guarded against white collar fraud came down.

These kinds of stories, which are far less operatic than the petty office politics dressed up as high melodrama by Bob Woodward, help show in a powerful way the cowardice and methods of the politicians and bureaucrats in the 1990s who set the stage for the destruction of our democratic system. The author describes a system of influence-peddling, financial rewards for unethical behavior, and of weakness. But he also, and this is where the book shines, talks about the individuals who ran this system. Jeff Connaughton is as close as you’re going to get to the point person for the financial reform fight. A former Wall Street banker, super-lobbyist, Democratic establishment player, and most recently, chief of staff to ardent crusading Senator Ted Kaufman in 2009-2010, Connaughton was the consummate insider who made enormous sums of money selling his lobbying services and connections to corporate elites. But something snapped in him in 2009, and he began to build a more honest life for himself, turning his deep connections and expertise on the nexus between Wall Street and Washington into a fight for reform of capital markets.

There are three stories in this book. The first is that of Jeff Connaughton, the Professional Democrat. This is the story of how Connaughton went to Wall Street after college, sought to break into Joe Biden’s inner circle, became a member of the permanent political class in DC, and then a co-founder of one of the biggest and most important lobbying firms, earning fabulous riches in the process. This is a process he maintains happens to thousands of young people in DC, turning them from idealistic potential agents of change into ardent careerist bureaucrats seeking wealth and access. The second is the financial reform fight, how Connaughton worked in the Senate as chief of staff for Senator Ted Kaufman, the replacement for Joe Biden and as Arianna Huffington put it in 2010, an “accidental Senator” and leader for financial reform. The third can best be described as how Connaughton transitioned from the first to the second. That piece of the story is seemingly simple – Connaughton lost a bunch of money in the financial crisis, and then he realized that Joe Biden had been a total disloyal asshole to him for decades, and he was tired of faking a good relationship with Biden just to make money as a corporate lobbyist. He had lost his taste for the game – the excitement, the money, the corrupt culture of DC. Connaughton really lays into his former boss Biden throughout the book, and I’m actually surprised the press hasn’t picked up on his vicious characterization of the current Vice President. The telling of the true nature of this important relationship has its purpose – he was willing to endure it for decades because DC has a feudal order, with lords and serfs. Connaughton was a “Biden” guy, and his loyalty to the system that paid him meant he had to stomach rank public dishonesty about it. It’s an echo of the financial fraud on Wall Street, where banks must pretend to be solvent even when they know they aren’t.

While most people will focus on the financial reform fight, how Connaughton became a member in good standing of the professional class is actually the best part of the book. As a 19 year old college student in Alabama, he invited Joe Biden to speak before a political group he had founded. Biden gave an impressive speech, and then signed a personal note that said, in essence, stay in politics. Biden’s human touch inspired the impressionable Connaughton, giving him the sense that being in politics had meaning. Politics would be the animating force for Connaughton’s entire life. After being convinced that Biden would be the Kennedy of his era, Connaughton spent a good amount of effort trying to get employment with the Senator, but couldn’t. So after college, he elected to go to business school, and then a Wall Street firm. After six years, he finally got his chance to work for what he assumed would soon be the Biden White House. He joined Biden’s 1988 Presidential campaign as part of the fundraising team. He wrote a campaign manual on fundraising called “The Bible”, which explicitly limited all access to Biden to those who would give money and encourage others to raise money in an Obama campaign-like Amway-style operation. It worked, and the Biden campaign was swimming in cash (for the time, anyway). But Biden lost the race in a plagiarism scandal. Ted Kaufman, who was on the campaign, brought Connaughton back to DC as a Senate staffer for Biden.

The Senate was a strange and disillusioning place for Connaughton. Though quite skilled, Connaughton never quite penetrated Biden’s inner circle. The problem was, he and Biden just didn’t like each other: “In Alabama, I’d watch him train his charisma beam on people of all ages and, as far as I could tell, win them all over. In Washington, he would do the same thing with complete strangers, especially if there was any hint that they might be from Delaware. Yet, behind the scenes, Biden acted like an egomaniacal autocrat and apparently was determined to manage his staff through fear.” At one point, Connaughton was sitting in a meeting where the staff were trying to get headlines for Biden on the problem of crack-cocaine addiction, and Connaughton realized that they were already doing a hearing and a press conference a week on it. The meeting was strategizing for political gain, and irrelevant to good policy; it seemed like they were looking for nine different ways “of skinning a cat”.

Connaughton soon left and went to Stanford Law School, becoming a clerk with Judge Abner Mikva. As it turns out, Mikva was brought in to be Bill Clinton’s General Counsel, which meant Connaughton would have a shot at his lifelong dream – working in the White House. So Connaughton sought Biden’s help to encourage Mikva to bring him to the White House, seeking to cash in on the chips he thought he had acquired with fundraising and Senate staff work. But Biden refused to call and put in a good word. “This isn’t personal,” explained a Biden staffer. Biden just doesn’t like Mikva. “Biden is an equal opportunity disappointer.” Another former Biden staffer consoled him this way: “Jeff, the difference between Ted Kennedy, who has spent decades promoting his staff into government jobs, and Joe Biden, is Kennedy believes in force projection. Kennedy Democrats share an ideology. Biden is only about himself becoming President, he doesn’t care about force projection, so he never helps his former staff get jobs.” Biden repeatedly shows up in the book, usually to pull some stunt like refusing to thank someone for busting ass on his behalf , condescending to Connaughton on the transition team,or trying to back out of a fundraiser after giving his word he’d show up. Connaughton is also Biden’s biggest fundraiser throughout, from the mid-1990s to 2008, even though the two have a relationship based entirely on image – Connaughton gets to pretend he’s close with Biden, and Biden gets to treat Connaughton as an afterthought to whom unpleasant duties can be foisted. The telling of this relationship isn’t sour grapes, it is meant to evoke the sentiment of fraud, not the Wall Street version, but how it worked in DC. Finance and politics paralleled each other, really as parts of the same system, though the tools and institutions differed depending on the industry.

Eventually, Connaughton makes it into the White House without Biden’s help. This is unusual, because Connaughton recognizes the dynamic of DC – you are always someone’s “guy”, and he was Biden’s, whether he liked it or not. That’s how the establishment worked, and the establishment always won (and still does win). At the White House, Connaughton fought the good fight against Wall Street, but was overwhelmed by Clinton’s weakness and Dodd’s alliances with the big banks. And then he left, and joined a law firm where he began working with Jack Quinn, a Democratic super lobbyist.

As he writes, “When I started lobbying, I was 38 and had few assets; no house, a cheap car, and a four-figure bank account. I’d made modest salaries in government and spent all my Wall Street savings on law school. I’d stayed in Washington for reasons that had little to do with issues or ideology; for me it was now mainly about establishing a DC profile, making money, and helping Democrats beat Republicans.” He, Quinn, and Ed Gillespie formed a powerhouse firm Quinn Gillespie, which was well positioned going into the 2000 election. Republicans and Democrats at the firm joked that they were all “members of the green party”. His firm’s motto was “we don’t lose sleep on election nights.” And because of Gillespie’s role in the Bush recount team, “a Bush presidency wasn’t my preference for the country, but it was great for our firm.”

This is a great part of the book, where Connaughton explains the wider circle of influence. “Professional Democrats are not just lobbyists. The term applies to almost all Democrats in the legal, policy, foreign policy, and even national security worlds, each one of whom is trying to climb the greasy pole of power.” These well-paid bureaucrats pass from a public position to a private position, hoping that Team Blue or Team Red wins so they can increase their monetary and political value. But the status quo is paramount, and anything threatening that brings the two teams together (as does, well, cash). This dynamic is well-covered by sociologist Janine Wedel’s Shadow Elite as a core element of corrupt economic organizations, this is a narrative documentation of it.

At Quinn Gillespie, Connaughton (a minor partner) helped design the modern corporate lobbying campaign. During the 1990s, corporate money spent on influence and campaigns tripled, and the culture changed. Quinn Gillespie led this change – the firm’s employees were early adopters of Blackberries, and the firm moved away from hourly billing to a compensation structure modeled on the financial services industry. Rather than lobbying being a spinoff of a large white shoe law firm, or the result of a key relationship between a former official and Committee chairs (like the original super lobbyist Tommy Corcoran), lobbying would now become about manipulating the press, implementing a grassroots campaign, and aggressive full-blanket coverage of Capitol Hill and the agencies. He described how the Banking Committee worked in this ecosystem – staffers close to Dodd and Shelby would leak tidbits to friendly lobbyists, who would relay them to clients. These clients would use the Financial Services Roundtable as a clearinghouse for this info, and it would circulate back out to the entire nexus of lobbying. Other staffers, even other Senators, would have no idea how to even find out what was in a bill, but K Street would have copies of it circulated and analyzed within a few hours.

The seedy anecdotes he details in this book are useful. He reminds me of scandals I had forgotten, like Hillary Clinton’s brother Hugh Rodham being paid $200,000 and securing pardons for two felons in the waning days of the Clinton administration. The narrative also throws the impeachment of Clinton into a new light, and gives the reader a glimpse of the rise of cable news as a vehicle for intra-elite dialogue. During that period, Quinn Gillespie supplied multiple surrogates to cable news to rebut the arguments put forward by Republicans. These surrogates included Jack Quinn, and then Connaughton himself. Connaughton was particularly skilled at this, and became a regular on the cable news circuit. His presence on TV generated accolades from friends, clients, and Republican colleagues. Impeachment was good for business, a sales opportunity. Over the course of the next ten years, from 1998 to 2008, Connaughton marinated in the world of DC, raising large sums of money for Joe Biden, working on behalf of corporate interests, helping Democrats get elected, and becoming a very wealthy man.

Then came the crisis, when Connaughton jumped from lobbying back into government, returning to his career as a reformer who wanted a strong public response to the crisis. In 2009, After Biden became VP, Biden’s former chief of staff Ted Kaufman was appointed to the Senate to fill the empty seate. Kaufman offered Connaughton a deal – become chief of staff, and they would spend two years doing their best to make a difference. Kaufman wouldn’t run for office, wouldn’t raise a dime in campaign contributions. Connaughton was already a millionaire, so the revolving door wasn’t particularly appealing to him any more. As with Barofsky’s path in SIGTARP or Elizabeth Warren’s at the Congressional Oversight Panel (and to some extent Alan Grayson’s work on auditing the Fed in the House), the circumstances were unusual enough to allow some genuine power to be exercised from the inside on behalf of the public interest.

Of course, we know what happened during the reform fight. The details Connaughton provides add to our understanding of how reform was undermined by various Senators and most importantly, the administration and Senator Chris Dodd. Kaufman starts out as a Senator excited to have the Bush administration gone, and having a high opinion of Geithner and the Rubinites. Connaughton, having been a high powered lobbyist and with a bit more of a real politick bent, knew this was nonsense from the get-go. Kaufman was disabused quickly. His first bill was to authorize a task force investigating criminality central to the crisis. It passed, with accolades for all involved, especially a freshman Senator who had hit the ground running.

Kaufman and Connaughton were excited that the bill passed, but soon noticed some problems. Senator Barbara Mikulski of Maryland, who had voted for the bill, was in charge of allocating the money for the new task force. And her staff simply refused to fund it. A high profile bill touting an upcoming criminal investigation was thus effectively turned into a press release. Connaughton was also hearing rumors from his long career in Democratic politics about Rahm Emanuel, “Two sources were telling me that Christine Varney, the assistant attorney general for the Antitrust Division, were complaining to friends that Rahm Emanuel, then White House chief of staff, had sent her a message: in effect, throttle back on antitrust enforcement, because the top priority is economic recovery. I was concerned that Attorney General Holder had gotten the same message about investigating Wall Street crime.”

The administration had a policy of not prosecuting, but Kaufman didn’t realize this until it was too late. They picked up clues early. Connaugton recalled a presentation by FBI official Kevin Perkins, who unveiled an “impressive” matrix of FBI investigations – but all of the targets were mortgage brokers and small timers, and there were no Wall Street banks on the list. At one point, they heard from the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, the office that had the resources to tackle Wall Street crime. His office’s main focus, he said, was cybercrime. Despite this, and that the SECs head of enforcement Robert Khuzumi continually brushed off Kaufman’s inquiries and oversight questions, Kaufman continued to defend him throughout his two years in office. Towards the end of his term, Kaufman was able to hold oversight hearings about prosecutions, but it was too late.

This dynamic of obfuscation and dishonesty in the process reappeared constantly and frustrated efforts at fixing the system. During the fight over the reform bill itself, Connaughton encountered what he called “The Blob”, a network of bank regulators, staffers, lobbyists, think tank denizens, and corporate officers who worked together to undermine efforts at reform [using a cover of partisanship]. At one point, he and Kaufman began criticizing the SEC for not ensuring that the short-selling process had effective rules to protect investors. A financial services lobbyist and former Dodd staffer threatened Connaughton, telling him it would be bad for his career if he kept going after short-selling. The two of them found the same problem in their attempt to deal with high frequency trading, where trading firms would use a variety of tricks and traps to squeeze pennies from investors and circumvent traditional stability enhancing rules for the equity markets. Largely ignored until the flash crash, Connaughton and Kaufman developed credibility on financial reform when the Dow inexplicably dropped by 1000 points in a few minutes. But the Blob was there, fighting against HFT reforms and aggressively seeking to weaken Dodd-Frank.

The Blob was aided in their efforts by the Obama administration and Chris Dodd. Dodd had insisted that the final bill would need to be as bipartisan as possible. This was, Connaughton notes, a cynical ruse to make the bill as weak as possible by claiming it needed to get GOP votes. The negotiating over the particulars of the bill were telling – Kaufman and Connaughton could get no info on what was happening behind Dodd’s closed door. Connaughton called his former lobbying partner, Jack Quinn, to vent about the secrecy of the process. Quinn was surprised, and said “I just spent 45 minutes with Dodd yesterday.” Wall Street, unsurprisingly, was writing the bill.

Eventually, Kaufman cracked the process open. He began blasting Dodd-Frank publicly, on the floor of the Senate. Dodd, miffed, called and asked him to stop saying bad things about the bill. Other Senators then got involved. Carl Levin and Jeff Merkley proposed the Volcker rule, which would crack down on prop trading by banks. Blanche Lincoln, in a cynical move to deal with a left-wing primary, got aggressive on derivatives reform. And of course, Sherrod Brown and Ted Kaufman proposed Brown-Kaufman, an amendment that would break up the biggest banks. This amendment struck at the heart of the financial crisis, proposing a genuine structural change in the banking system.

The reaction of different Senators and administration officials to the bill, and to the Brown-Kauman amendment specifically, was telling. Harry Reid wouldn’t talk Wall Street reform even though he knew that blasting Wall Street was a vote getter, because Wall Street was bankrolling his 2010 campaign. The cynical Senator and Democratic whip, Dick Durbin, noted that “the banks own the place” but then said that breaking up the banks was going “a bridge too far.” Durbin even said to Kaufman at one point, “Jamie Dimon asked me to tell you ‘it was the small banks that failed'”. Tim Geithner said the administration would deal with Too Big To Fail Banks at Basil, through capital requirements negotiated at the international level. Republican Banking Ranking Member Richard Shelby assented to all of Dodd’s unanimous consent requests because he knew that Dodd wanted the weakest bill imaginable. And though newly elected Senator Scott Brown wanted to punch a hole through the Volcker rule, the Obama administration actually wanted a bigger loophole than Scott Brown did for proprietary investments by banks.

My favorite Senatorial reaction was from Dianne Feinstein. Dodd, knowing Brown-Kaufman was gaining strength but didn’t yet have enough votes to pass, called a snap vote. Connaughton wrote about the vote that “no one could confuse the issue, or so I thought. But, just before voting, Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) – one of the most liberal members of the Senate — asked Durbin, the majority whip, “What’s this amendment?” According to Durbin, who later told Ted, he replied, “To break up the banks.” Giving the thumbs-down sign, Feinstein said bemusedly: “This is still America, isn’t it?”

Connaughton and Kaufman fought, as aggressively as they could, for two years. And Connaughton is clear-eyed about what happened. They had accomplished very little, and his career in Democratic politics and on Wall Street was over. As he put it in the conclusion of the book, “In Washington, as a Professional Democrat, I could count on the corporate marketplace to play me for the value I provided in access, insights, strategy, influence, hard work and – most especially – results. In politics, the box comes with no guarantee. When I finally opened mine, it was empty.” The corporate world pays for results, the political world is simply about the random luck you have in working for a Joe Biden who isn’t a disloyal asshole. Wall Street and the K-Street empire it supports, in other words, is reliable. The electoral world isn’t.

Most books on politics with a polemical edge end with some sort of uplifting narrative. The narrative goes, here’s this insurmountable terrible problem, but we can fix it, somehow, somewhere. The Payoff is not like that. At a certain point, Kaufman suggested that the two of them start a nonprofit to continue their reform fight, but Connaughton turns him down and leaves to live a different kind of life in Georgia. He has no illusions about the power of Wall Street and the political system. It isn’t fixable within the current model. Nonprofits are outgunned, political money is too powerful, and the careerist allure Professional Democrats and Professional Republicans is overwhelming. He has no solutions, just his own witnessing of how the people who rule us think and act when we’re not in the room.

Connaughton is going to pay a heavy price for this book, and for his reform-minded behavior in the last three years. He told stories that you aren’t supposed to tell, gives away open secrets that should remain circulating only among insiders. He blew up his connections in the world of politics, burned all his insider bridges. I don’t quite know why he wrote this book – though the book itself is deeply pessimistic, the act of writing is in and of itself an act laden with hope. I don’t think Connaughton necessarily included his real motivations in the book. It’s not as if he says that he met a victim of his earlier career, and realized what he had done. Perhaps he lost a bunch of his wealth in the crash, which opened his eyes to the mirage of what wealth was. Then, he was a helper on Biden’s transition team, but was kicked off because he was a lobbyist who had raised Biden money. It seems actually that his turn was completed because he realized that the relationship with Joe Biden, the man who had inspired his life’s work – was based on fraud, narcissism, and transactional dishonesty. And the timing of Ted Kaufman’s ascension to the Senate was the final kicker.

Sometimes, circumstances and a conscience can intrude at opportune moments. It seems like that’s what happened with Connaughton and his remarkable last two years. And now, he has quit the game, with this book — and perhaps “The Blob”, which may join the vernacular – as his legacy. He tried his best for two years, and it wasn’t enough. The fight is over, and the bad guys won. It’s a sad conclusion for someone like Connaughton, and for all those who fought the good fight over the last four years. But it’s hard to argue he’s wrong.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein could not bother to know? Since when would she give up the chance to squeeze someone for a perk/pork? What she did was buy some cover, an act of real cowardice, as well as political corruption. Her dear hubby/bagman must have picked up quite a sum for her performance here.

the whole system is so corrupt, i’m pessimistic that it can ever be fixed.

For me, its even beyond that. When I read this, and books like “This Town” by Liebovich, I am struck that there is very little ‘system’ left to fix – its more akin to giant skimming operation than a form of government. Money, power and influence – leading to more money – is the only object for the players at this exclusive club.

Then, its all about keeping the music playing……

Could Rome have been “fixed” 50 years before it fell? There are inevitable cycles in human affairs, and America must come to its natural end. The story will continue in the next chapter, with different settings and characters, but otherwise the same as always.

Connaughton’s description of “The Blob” resembles Marx’s description of the French finance aristocracy:

“Since the finance aristocracy made the laws, was at the head of the administration of the state, had command of all the organized public authorities, dominated public opinion through the actual state of affairs and through the press, the same prostitution, the same shameless cheating, the same mania to get rich was repeated in every sphere, from the court to the Cafe Borgne to get rich not by production, but by pocketing the already available wealth of others, Clashing every moment with the bourgeois laws themselves, an unbridled assertion of unhealthy and dissolute appetites manifested itself, particularly at the top of bourgeois society- lusts wherein wealth derived from gambling naturally seeks its satisfaction, where pleasure becomes debauched, where money, filth, and blood commingle. The finance aristocracy, in its mode of acquisition as well as in its pleasures, is nothing but the rebirth of the lumpenproletariat on the heights of bourgeois society.” – Karl Marx, The Class Struggles In France, 1848-1850

Democrat party’s collaboration in the looting of the American state…

“The party that leans upon the workers but serves the bourgeoisie, in the period of the greatest sharpening of the class struggle, cannot but sense the smells wafted from the waiting grave.” – Leon Trotsky

Who owns *Wall Street*, and to what end? It’s deep.

Please place History related by VIPs in this blog within the Frame of motives suggested by the works below:

“Who Owns America? A New Declaration of Independence” –Edited by Allen Tate and Herbert Agar (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1936);

and

“RUNNING COMMENTARY: The Contentious Magazine That Transformed the Jewish Left Into the Neoconservative Right” by Benjamin Balint (New York: Public Affairs, 2010);

and

“Total War Against Gaza: Israeli Genocide and Its Willing Accomplices” by James Petras on 08/11/2014:

http://www.globalresearch.ca/total-war-against-gaza-israeli-genocide-and-its-willing-accomplices/5395492

Get the picture?

Great Marx quote, thanks.

Re Trotsky, as yet US elites aren’t troubled by olfactory-based premonitions of anything other than bad sushi.

‘… scandals I had forgotten, like Hillary Clinton’s brother Hugh Rodham being paid $200,000 and securing pardons for two felons in the waning days of the Clinton administration.’

Matt Stoller casually libels the Clintons by claiming that they work so cheaply. In fact, they made a LOT more than a crappy $200K for their exemplary services:

[Hillary’s] brother, Hugh Rodham, was paid more than $400,000 for his successful efforts to win pardons for a businessman under investigation for money laundering and a commutation for a convicted drug trafficker. He eventually returned the money at his sister’s request. [‘Please, Hugh. People will think we were in this just for the money!’]

In the closing hours of his presidency, Bill Clinton pardoned 140 people, including billionaire financier Marc Rich, who fled the United States in 1983 rather than face charges of tax evasion, fraud and making illegal oil deals with Iran. Rich’s ex-wife, songwriter Denise Rich, contributed $450,000 to the Clinton presidential library project, $1.1 million to the Democratic Party and at least $109,000 to Hillary Clinton’s bid for the Senate.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/07/06/AR2007070601185_pf.html

That’s a cool $1.659 million by my count, not including the original $400K in a brown paper bag with Hugh Rodham’s fingerprints all over it — way beyond Matt’s lurid insinuations of ‘dirty deeds done dirt cheap.’

The title says it all, namely the word “professional”.

It may be time to limit any active political career to 1 term of maximum 4 years in order to reduce corruptive behavior. – Just a thought.

re: why he wrote this book

There are many who write nonfiction works because they think the topic is “hot” or “current” and therefore likely to sell well. There are also, however, who write to exorcise something from their psyche, something that has been eating away at them for years, and in the end it matters very little if it sells, because the book is a confession (in the manner of, say, Augustine) rather than an exposé. I can imagine, after years of prevaricating for a living, that it would be quite refreshing to simply describe things as they are in plain, simple terms.

Lambert, a reminder of a very important piece published in July 2006 appeared today as a sub-link to current discussion. I’d never seen it before, and was astounded by its importance today, as more of the People are waking up and asking questions. It’s an essay by Norman Liverpool, entitled” “The New Totalitarianism: Rule Through Barbaric Annihilation”

The title immediately brings to mind the complex work of Goetz Aly, presented in two books:”Architects of Annihilation: Auschwitz and the Logic of Destruction” by Goetz Aly and Susanne Heim (1991), translated by Allan Blunden (2002), and “HITLER’S BENEFICIARIES: Plunder, Racial War, and the NAZI Welfare State” by Goetz Aly (2005), translated by Jefferson Chase (2006). BUT Liverpool shows that the New Totalitarianism puts Hitler’s “Architects of Annihilation” to shame!

Indeed, in 2006 Norman Liverpool squared the circle succinctly when it came to the definition of “Totalitarianism” in this “New” form. It is indeed new because of advances in technology. It surpasses in concentrated barbarity and monstrous demonic evil the “Totalitarianism” of Arendt and the “Inverted Totalitarianism” of Wolin by far. It makes us realize how very polite Michel Chossudovsky has been in his essays/blogs, lectures, and books, as he has given his all to warn humanity of inconceivable peril to our existence.

Lambert, please read and consider the power of this essay within your genteel frame of potent discovery at Corrente and NC. Emeril Lagasse’s phrase might be employed here, without trivializing the import of how you might “kick” the discussion “up a notch” even as you recognize what the commentariat can bear. What discretion is required not to terrify your readers with the stark truth spoken so perfectly in print by Norman Liverpool in 2006 — Pirandello’s “l’azione parlata” (“spoken action”) at its best. But isn’t it true, Lambert, that we the People must face it together, and that there is no better place for facing it together, than in the Internet forum friendly to thinkers, known as Naked Capitalism?

Approriate to this forum’s platform for thinking, the link below tells the Naked Truth. Who grateful we must be for the foresight, wisdom, and lucidity that stands behind the *truth archives* (perhaps akin to the mysterious “Akashic Records”) on tap at GlobalResearch.ca.

Behold the Naked Truth in a nutshell:

http://www.globalresearch.ca/the-new-totalitarianism/2794

Why are we here, Lambert? What is the meaning of our lives?

Thanks. I’ve gotta say, though, I take Global Research with a dose of salts.

Oh, I don’t know…I get a fair amount of insite and first reports there that make it worthwhile. It’s difficult enough to get real news these days that you have to follow whatever you get.

I click through to their sources sometimes, sure. Why not?

Lambert,

I’ll second that thought, however, I’ve got to the stage whereby I’m highly sceptical of most of what I read online, actually sceptical to the point of paranoia. Further, and I’m honest about it, I’m an out and out “propagandist” for leftwing political opinion (intertwined with a large dose of ecological concerns), which in my humble opinion needs to be aired in these times of acute censorship and closing down of dialogue to represent one view only. And if only one view exists, as JS Mill pointed out in “On Liberty” you cannot claim to live in either a liberal society or a democratic society.

“Clinton, even in opposition to big finance, cowered before the opinions of the establishment.”

Clinton knew exactly what he was doing. He wanted the 6 figure speaking fees from the banksters when he left office. He wasn’t going to rock the boat.

When people bring up politics I have a canned response. “The only thing I hate more than politics are the scummy politicians, regardless of party label” I am not sure if people realize how sincere I am when I say this. One day they may.