The Republicans have been quick and shameless in using their control of both houses to try to crank up the financial services pork machine into overtime operation. The Democrats at least try to meter out their give-aways over time.

Their plan, as outlined in an important post by Simon Johnson, is to take apart Dodd Frank by dismantling key parts of it under the rubric of “clarifications” or “improvements”* and to focus on technical issues that they believe to be over the general public’s head and therefore unlikely to attract interest, much the less ire. However, as Elizabeth Warren demonstrated in the fight last month over the so-called swaps pushout rule, it is possible to reduce many of these issues to their essential element, which is that Wall Street is getting yet another subsidy or back-door bailout.

Today’s example is HR 37, with the Orwellian label “Promoting Job Creation and Reducing Small Business Burdens Act”. We’ve attached it at the end of this post. The Republicans sought to get it passed in the House on Wednesday using a fast track process referred to as a suspension of the rules, which is used for supposedly non-controversial bills. But the Republicans overplayed their hand. Enough liberal and banking reform groups lobbed objections to secure enough votes to prevent the bill from passing.

An overview from the Wall Street Journal:

A push by House Republicans to roll back a series of Wall Street regulations failed to advance Wednesday amid resistance from Democrats, an unexpected setback for the GOP’s efforts to use its increased majority to ease financial rules.

Republicans were six votes short of the two-thirds support needed to advance the legislation, which included a controversial delay to a provision stemming from the 2010 Dodd-Frank requirement that banks sell stakes in certain complex securities. The bill failed by a vote of 276-146…

While the bill includes nearly a dozen modest provisions that had cleared the House or individual committees as stand-alone measures in the last Congress, Democrats focused their objections on one provision that would have delayed restrictions on bank ownership of certain debt securities. The restrictions, part of the so-called Volcker rule prohibiting banks from making risky bets with their own money, applies to bank ownership of collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs, which are complex securities that bundle together corporate loans as well as bonds…

“They had 11 bills in one and we thought that it needed to go through more of a process,” said Rep. Elijah Cummings (D., Md.)…

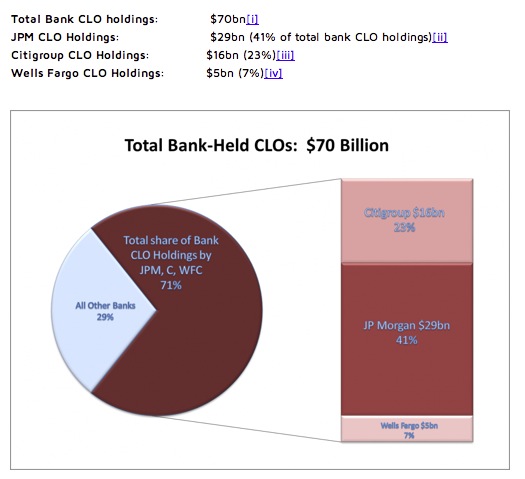

The “Volcker’ reprieve would have given banks until 2019 to sell their stakes in CLOs, benefiting J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., Wells Fargo & Co. and Citigroup Inc. that hold the largest CLO stakes, according to data compiled by SNL Financial last year.

Though the Federal Reserve has already given banks until 2017 to comply with the CLO restrictions, supporters said an additional delay is needed to prevent “fire sales” of the securities, which could cause banks to suffer big losses.

We don’t agree that all the other measures were so modest, but the CLO matter is indeed a big deal.

CLOs are a type of collateralized debt obligation. They are made of risky corporate debt exposures: leveraged loans, junk bonds, or credit default swaps on high-risk corporate borrowers. Their structures are less risky than the type of asset-backed CDOs that blew up the global financial system. The flip side is that because the CDO meltdown was so dramatic and had such devastating consequences, the fact that CLOs took big mark to market losses in the crisis has been largely ignored (and like other complex, risky securities, the realized losses, which in the end were inconsequential, would almost certainly have been higher had the Fed not engaged in such heroics to goose asset prices and enable weak borrowers to refinance cheaply.

As Better Markets explains in a useful backgrounder, CLO exposures are concentrated at the biggest banks:

And they play two critical roles: helping banks finance private equity deals, which are a huge business for them, and as trading vehicles for their own account. As a Bloomberg article in February 2014 explained, tightening up on CLOs would restrict private equity funds’ ability to get cheap credit.

To unpack this issue a bit, let’s turn again to the Better Markets backgrounder:

What are CLOs?

- CLOs are investment funds that consist of “leveraged loans”, (huge, low-rated, corporate loans) which can be swapped in and out by the manager throughout the life of the fund. Investing in a CLO is functionally identical to investing in a hedge fund that invests in this kind of loan.

- CLOs held by banks were – and continue to be – proprietary positions. Beneficial capital treatment of CLOs meant that banks could borrow cheaply and hold high-yielding CLOs on their books, capturing the difference as profit.

- The specific features of CLOs (when it will mature, the kinds of investments it can make, the rights and protections for each class of investor, etc.) are not publicly disclosed and are non-standardized, so it is impossible to know how many CLOs exist with any given feature.

- Importantly, it isn’t clear which CLOs, or how many, would be affected by any change in the rule.

Keep in mind that CLOs that consist entirely of loans are excluded from the Volcker Rule. But a bank would generally create that type of CLO only for sale to third parties, so they would seem to fall outside the Volcker Rule on that basis (ie, this provision was a belt0-and-suspenders measure to clear up any ambiguity).

And the CLOs that the banks are keen to keep in-house are crucial for private equity firms, who are the biggest source of investment banking revenues for all of Wall Street. From a February 2014 BusinessWeek article:

Leveraged loans held in CLOs are “crucial” for leveraged borrowers, Elliot Ganz, general counsel at the LSTA [Loan Syndications and Trading Association], said in a telephone interview. “They are pretty much the only source of funding for many of these companies.”…

CLOs, a type of collateralized debt obligation that pool high-yield, high-risk loans and slice them into securities of varying risk and returns, were the largest buyers of leveraged loans last year, with a 53 percent market share, according to the New York-based LSTA.

That percentage has almost certainly gotten higher. As structured credit maven Tom Adams said by e-mail last month:

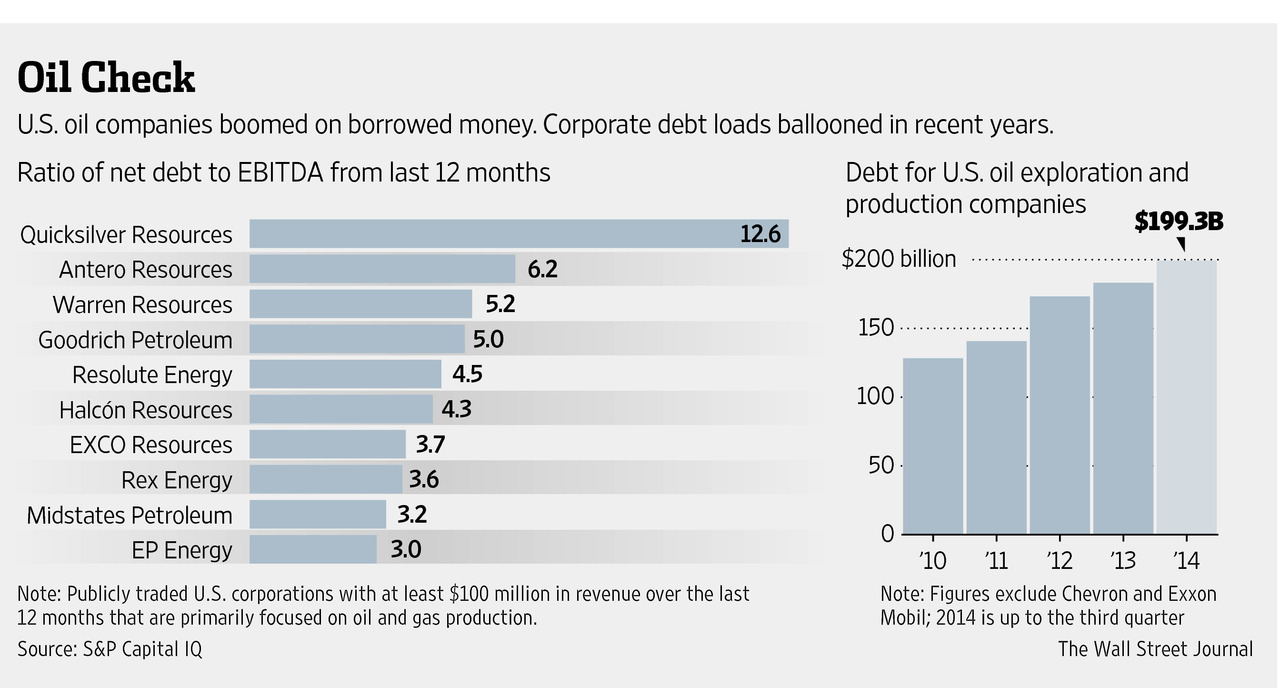

Much of the recent energy boom has been financed with junk debt and a good portion of that junk debt ended up in collateralized loan obligations. CLOs are also big users of credit default swaps, which an important target of the Dodd Frank push-out. In addition, over the past 6 months banks were unable to unload a substantial portion of the junk debt originated and so it remained on bank balance sheets . That debt is now substantially underwater and, potentially, facing default. To hedge or hide the losses, banks are using credit default swaps. Hedge funds are actively shorting these junk debt financed energy companies using credit default swaps (it’s unclear where the long side of those CDS have ended up – probably bank balance sheets and CLOs).

Finally, junk financed energy companies have been trying to offset the falling price of oil by hedging via energy derivatives. As it turns out, energy derivatives are also part of the Dodd Frank push-out battle.

Conditions in the junk and energy markets are pretty dire right now as a result of the collapse in oil, as you know. I suspect there are some very anxious bank executives looking at their balance sheets right now.

Since the derivatives push-out rule of DF was scheduled to go into affect in 2015, the potential change in managing their exposure may be causing a lot of volatility for banks now – they need to hedge in large numbers at the best rates possible. Is it possible that bank concerns (especially Citi and JP Morgan) about the potential energy markets are why DF has to be changed now?

The reason to expect such heavy concentration of energy debt in CLOs is that energy debt has made a big increase in its total share of the junk bond market, up from 4% ten years ago to 16% now. 16% might not seem like a big deal until you realize that the real increase in energy credit issuance happened in the last few years, so the proportion of energy borrowing to total risky borrowing was vastly higher of late so as to move the averages so much in a short time. And CLOs tend to have the heaviest exposure to the newest deals; for instance, with managed CDOs in the runup to the crisis, CDO managers would swap out older vintage subprime exposures for more recent vintage deals.

Needless to say, the outlook for energy prices and therefore energy-related debt has gotten only worse in the last month. As we’ve written repeatedly, and the Wall Street Journal confirmed yesterday, many US shale gas companies are continuing to operate at losses because they need the revenues to pay creditors. That means the supply glut and depressed prices will continue until their access to funding is cut off. And the longer the glut continues, the more companies will eventually run out of financial rope. From the Journal story:

Their need to service that debt helps explain why U.S. producers plan to continue pumping oil even as crude trades for less than $50 a barrel, down 55% since last June….

Energy analysts warn defaults could be coming. “The group is not positioned for this downturn,” said Daniel Katzenberg, an analyst at Robert W. Baird & Co. “There are too many ugly balance sheets.”

The industry is also expecting a wave of asset sales and consolidations…

And mergers aren’t a panacea.

“To be a consolidator of a company that has a large cash-flow hole, you have to have the ability to fulfill that cash-flow need,” said Dennis Cornell, managing director and head of energy investment banking for the Americas at Morgan Stanley. “You can’t expect two companies with big problems with their cash flows to come together and mitigate that problem.”

So ironically, one of the industry justifications for not wanting to unload CLOs now is true. They’d take big losses because future price declines are baked in. To put it another way, the values at which they are carrying them on their balance sheets are certainly inflated. Recall that it was widely believed that during the crisis, banks were similarly holding CLOs that were under water. They traded itty bit exposures with each other and with friendly hedge funds to establish fictive prices and justify the marks on their books.

And the irony is that if the banks had been forced to implement the Volcker Rule on a timely basis in the first place, they wouldn’t be sitting on losses that they are keen to hide.

This isn’t the only gimmie, as opposed to fix, in this bill. Oddly, just about no media account has taken notice of a provision, Title IV, which starts on page 8, which gives private equity firms a “get out of liability free” card for acting as unlicensed broker-dealers, at least on small and medium-sized transactions. As we discussed earlier this week, broker-dealer liability is a nuclear weapon for the SEC in enforcement negotiations with private miscreants. So it’s hardly surprising to see that the industry has tried burying it in alongside other innocuous-seeming fixes, like allowing companies with less than $50 million in revenues to opt out of electronically tagging their annual reports to the SEC.

There is a bit of good news in this generally sorry but all too typical picture. Even though the Republicans can clearly get the bill passed in both house through normal processes, Obama has said he will veto this bill. That means the Democrats will put up at least a bit, and perhaps even more than a bit, of a fight. That in turn means the Republicans will need to offer enough in they way of concessions for Obama look like less than a total sellout (admittedly a low bar).

If the Republicans get stupid and bargain too hard, the process could take long enough that it drags on into the time when CLO losses become a hot topic in the business press. That would make it clear what this bill is really about and also require that Obama get a bit more than a cosmetic redo. In other words, the longer the negotiations go on, the more the climate will change to make it harder for each side to give ground and reach a deal. I’m not saying this scenario is likely, but this means there actually is reason to fight, and for you to call your Congresscritters and tell them you are sick of bank bailouts and you expect them to vote against HR 37.

____

* As we’ve said repeatedly and consistently in past posts on Dodd Frank, we consider the bill to be grossly inadequate. Moreover, it was designed to be weakened over time, with many critical issues relegated to studies and others set for delayed implementation, which as we can see here, allows the banking industry to keep fighting a rearguard battle. We’ve also stated that while we agree with the Volcker Rule in concept, its particular implementation left a lot to be desired, and we’ve discussed some easy-to-implement remedies. But even this weak reform is better than nothing, and the Republicans are clear about their agenda: “We disagree with all of Dodd-Frank.”

I’ve never understood why “held to maturity” valuation was ever permissible in bank balance sheets. There is an argument that in illiquid assets, having to mark to market induces undesirable volatility in valuations — or even makes accurate valuing impossible. In which case, in my opinion, such “assets” (and this term could be completely illusory) have no place being on the books of any systemically important institution. I’m assuming here that the banks are classifying the CLOs as held to maturity (otherwise they’d have to be marked to market and wouldn’t be such as issue).

Whenever I see “held to maturity”, I automatically assume that there’s hiding of losses / can kicking going on.

These ought to be marked to market. Jamie Dimon did get away with what amounted to a “hold to maturity” valuation with risky derivatives such as the London Whale trades because bank treasuries are allowed to have special inventories called “available for sale” which are supposedly for assets used to manage bank liquidity. Those assets are NOT marked to market even though they can be traded freely.

As I explained but perhaps not clearly enough in the post, these CLO values were faked in the crisis by creating phony market values. I probably should have been explicit, they are (or ought to be) valued on a mark to market basis.

Thanks – hadn’t appreciated there was a third possibility (that while the CLOs are marked to market valued as opposed to held to maturity valued, those market to market valuations are subject fakery). And I thought I was too cynical about bank balance sheets… I’m not nearly cynical enough obviously.

“the fact that CLOs took big losses in the crisis has been largely ignored.”

Can you please provide source/data? I don’t know much about US CLO market, but EUR CLO market was generally ok, and I was under the impression that even in US the CLO losses were in low-single percentages (so if tranched, wiping out equity and junior, but not much senior losses).

I agree that that pure oil CLO (if there are any), or ones with substantial oil exposure, are likely to suffer significantly in the coming year or so.

They took losses in MTM terms. They were marked only to the mid-lower 80s and that was even after all the funny business. Everyone was expecting a refi train wreck in 2012-2014 when the loans matured but ZIRP took care of that.

https://www.babsoncapital.com/BabsonCapital/http/bcstaticfiles/Research/file/The%20Opportunity%20in%20Snr%20CLO%20Notes%20200906%20Final.pdf

Chart in Figure 2 refers. The spreads heading for the moon in the GFC reflect lower pricing (in fixed income, of course, higher spreads mean lower asset pricing). This paper is also a useful guide to the thinking behind the attraction of the CLO (at least in the minds of those selling them).

There has been some recovery since the dark days of 2007-8 (not least because of central bank asset purchase support). But that recovery now looks, as per Yves’ piece, not (cough) necessarily a given.

The big issue, which I probably should have unpacked more in the post, is the reason the old CLOs performed well was diversification, in that the default correlation models really did do a good enough job, along with the loss buffers, of mitigating risk, particularly given that the Fed’s protracted super easy money allowed a lot of shaky credits to refinance at unbelievably low rates. The cheap refis made them better able to service debt.

With the increased concentration of energy debt, which is inevitable given the energy boom, plus correlations the modellers likely missed (for instance, banks in Texas and North Dakota will be in a world of hurt), the diversification is almost certainly less good. If the energy bust goes on long enough, we could see not just MTM losses but actual losses. MTM losses are a real issue because…drumroll…they reduce trading profits and hence bonuses. And they do at the time reflect market beliefs about real value. They are not to be dismissed as “oh of course this will recover.” Maybe yes, maybe no.

The disturbing thing is not enough is known about these CLOs, particularly given their fluid nature, where things really stand.

Telling readers that banks hold $70 billion of CLOs on their balance sheets is a great way to make this seem like a huge problem and scare readers. What you fail to include is how much of that $70 billion is comprised of AAA CLO tranches … you know, the ones that have NEVER defaulted in the history of CLOs!

You also failed to note that most post-crisis (and post Dodd-Frank) CLOs now only consist of loans. The pre-crisis vehicles that included bonds, derivatives, and god knows what else are quickly maturing and being redeemed.

Finally, I would ask you to stop using “derivative” and “credit default swap” as fear mongering buzzwords without any critical analysis. How exactly are banks/funds acting in bad faith by purchasing protection against potential losses? Isn’t that a responsible thing to do?

I suggest you reread the post. You are either deliberately or via overly hasty reading straw-manning it. The headline says “Gimmie” not “Rescue” or “Bailout in the Making.” The figures are accurate and the post talks about MTM and possible actual losses.

The new CLOs clearly are not entirely loans or else you would not have seen the market disruption reported in the early 2014 Bloomberg article that we linked to in the post on how Volcker Rule implementation worries were disrupting private equity transaction financing. The sources were very clear that restricting CLOs held by banks to loan-only would be damaging to them. It still is the case that only the ones that are not loan-only are subject to Volcker Rule treatment and need to be wound down, allowed to mature (many would by 2017, the current cutoff date) or sold. However, the story discusses at length how CLOs rebounded because banks and investors became optimistic that the SEC would allow banks to hold CLOs on balance sheet that had “optionality” which in layperson terms means they could hold exposures other than just loans. According to the Better Markets backgrounder, that has not happened.

So that article contradicts your claim re “most CLOs consist only of loans.” That may be true when you are including ones sold to third parties, since many CLOs are sold, not retained, but we are speaking here only of the ones on bank balance sheets.

And as we indicated, the credit exposures in these CLOs are now likely more correlated than the ones before by virtue of the heavy concentration in the market of energy loans and unanticipated correlations to energy prices due to the sharp fall in energy prices, which if it continues long enough will produce regional downturns that will hit all sorts of business that are have large revenue exposures. Thus past performance may not be a reliable guide.

I never stated that any of your figures are inaccurate — I indicated that they are incomplete, and perhaps intentionally misleading. MOST bank holdings of CLO securities consist of AAA tranches, which have never defaulted and are unlikely to do so without an extreme disruption much greater than what we saw in 2008-2009 (the worst financial shock since the Depression). Claiming that CLOs suffered MTM losses during the downturn then quickly recovered when the panic subsided reinforces the prevailing wisdom that marking highly-rated, senior tranches in a distressed market is foolish and unnecessary.

I’m not sure where you got “Rescue” or “Bailout in the Making” from my post, but I would say that even “gimme” is a gross misrepresentation. Classifying this as a “gimme” implies that banks should be forced to take trading losses selling off highly-rated, extremely safe assets that they had originally purchased legally.

I exaggerated a bit when I implied that all post-crisis CLOs excluded bonds, but it has certainly moved in that direction as Dodd-Frank/Volcker has come into focus: http://www.forbes.com/sites/spleverage/2014/03/07/leveraged-loans-clos-tap-volcker-compliancy-options-await-relief-hopes/

“For deals that priced in 2013, Morgan Stanley estimates that bonds … accounted for 1.16% in U.S. CLOs.” I don’t have time today to find aggregated 2014 figures, but the trend of removing bonds to accommodate Dodd-Frank/Volcker continued throughout 2014, and the proportion of loan-only CLOs is quickly increasing as compliant new issues (i.e. no bonds) replace maturing older vehicles.

Yes, Volcker talk briefly rattled the market early in 2014, but managers quickly shook that off by issuing compliant loan-only CLOs. The 10,000 pound elephant in the CLO market now is “risk retention” — investors are hesitant to commit to long-term vehicles managed by issuers who might be regulated out of business in a few years. I’m all for rational regulation, but blunt, blind restriction is senseless and damaging. This is where industry advocates and Republicans will likely focus their attention, and they will be justified in doing so.

As for your final argument that concentration in energy and higher correlation pose greater threats this time around, this is again misguided. According to Intex, US CLO exposure to oil and gas issuers is only 3.5%. Even if all of these O&G loans defaulted and recovered 0% (won’t happen), this would only dent the equity tranche of the average CLO. Most mezzanine tranches won’t even be affected by a spike in energy defaults, much less the senior tranches that banks typically hold. CLO 2.0s are also less leveraged than the 1.0s that performed fairly well through the crisis, so if you really believe that “past performance may not be a reliable guide” in this specific situation, you must be stocking your bunker with canned food and guns.

It is quite intriguing how you continue to straw man our argument and present carefully selected “facts”.

First, CLOs showed ~15%-20% MTM losses during the crisis with heavily manipulated marks. That was a rational forecast for potential losses given the large number of junk issuers that had debt maturing in 2012-2014 and their ability to refinance then was in serious question. What kept CLOs from showing losses that would have otherwise been incurred was the impact of all the rescue efforts which enable issuers to refinance at extremely favorable rates due to the considerable decline of risk-free rates and the deliberate effort by the Fed via QE to compress risk premia, which helps risky credits most of all. So to argue that CLOs performed well is narrowly true but substantively misleading.

Second, the crisis last time around was all about housing debt. CLOs were not directly exposed. This time, the crunch is concentrated precisely in their terrain. By all accounts, banks have been unable to sell any CLOs since July or so, which is worryingly parallel to the shutdown of the subprime market in 2007.

We have pointed out that CLOs, not being resecuritizations, are not subject to catastrophic fails as asset-backed CDOs were. But being better does not mean not being exposed to the risk of losses.

To turn to the details of your argument, your opening paragraph is effectively an argument against mark to market accounting in times of stress. While that was a successful tool during the crisis, it of course created zombie companies, especially for banks, because no one knew what they had on their balance sheets or what it was worth. Hardly a ringing endorsement and not one that any investor in such companies would want. And as Better Markets points out, this really amount to an argument for paying higher bonuses. Failing to book MTM losses allows for higher reported profits. Trading desks don’t allow traders to finesse their marks this way to pay themselves higher bonuses (except to the degree that management is in cahoots with the traders; you never saw this sort of behavior when Wall Street firms were partnerships). Why should policymakers tolerate it, particularly given the considerable economic costs of the crisis?

Your next paragraph is diversionary but even so is unintentionally revealing. Investors don’t like non-compliant issuers (i.e., issuers with no skin in the game), but forcing issuers to be compliant is somehow not rational regulation? How is skin in the game “blunt blind regulation”? The problem, of course, is that CLO issuers are typically lightly capitalized (in layperson speak, fly by night) entities who have no ability to honor their commitments in distressed markets. This works well for Wall Street and for banks – the risk of high yield loans is quickly off-loaded and then they make more money on fees. That doesn’t make the situation rational or good in any particular way.

Finally, the the 3.5% concentration figure is often bandied about. That is for the aggregate CLO market or the top 25 issuers, depending on the source. That is another obvious deflection. Who cares what was issued in 2007 or what those deals hold? It’s just like the arguments made back in 2007 that subprime was only 15% of the aggregate mortgage market – completely and deliberately obscured the issue. What is germane is what the energy concentrations are for the 2013 and 2014 deals, and most important of all, the ones that banks are holding now that the music has stopped. I suspect many are at their maximum concentrations for energy and others have gamed the concentration limits. In addition, the odds are high that there is major adverse selection for the ones that are on bank balance sheets – the deals for which there was weak investor demand are they ones with higher energy concentrations and they ended up at the banks. The fact that Citi has been pushing for this is a pretty good indicator. Citi was the 2nd largest underwriter of ABS CDOs but they never actually sold a single bond: all of those deals ended up on Citi’s balance sheet, either directly or through off-balance sheet vehicles. This happens repeatedly in the securitization market – easy to get to the top of the league tables if you don’t have to sell to third parties, see GE/Kidder in the 1990s. Since there was basically no punishment for that last time, it’s reasonable to be concerned that it could be happening again, particularly in light of how aggressive the bank lobbying has been.

As to your comment re “most” being AAA rated, that’s close to a tautology since the structures have more than 50% of par value in the AAA tranches.

Derivatives expert Satyajit Das provided confirmation by e-mail:

1. I am aware that banks are sitting on a lot of CLO paper of all ratings as inventory.

2. The amount of energy related paper is more difficult to know. But some general data provides a guide. Energy companies now make up around 15 percent of the Barclays US Corporate High-Yield Bond Index, up over 300 percent from less than 5 percent in 2005. Since 2010, energy producers have raised US$550 billion of funds, through new bonds issues and loans. In 2014, over 40 per cent of new non-investment grade syndicated loans were to the oil and gas sector. Given that the CLOs have been using non-investment grade loans you would expect significant energy exposures.

Who gave AAA ratings to the CLOs to which you refer? Was it the same ratings companies that gave AAA ratings to pure junk in the years immediately prior to 2008? If so, there could be a credibility issue…

Republicans take control of congress and the democrats find a (little bit of) spine. Bet if the Ds would have swept the last election, this would have sailed through with nary a whisper.

No surprise here. When you are a bunch of bought and paid for street whores like the GOP, desperate for Wall Street crack in the form of campaign donations, you perform whatever obscene act the john pays for.

No argument, except to say that the exact same thing applies to the D-Team. Ever see those Presidential cufflinks on Jamie – Obama’s my bitch – Dimon??

I can’t help but snicker at the fact the Republicans are calling the bill: “Promoting Job Creation and Reducing Small Business Burdens Act.” It’s the same canard they always push, where we are supposed to fantasize about being entrepreneurs and “small business” owners. This fantasy is aimed squarely at your middle or lower middle class American. I know he probably doesn’t draw much water on this blog, but Marx explicitly outlines in Das Kapital why this position is contradictory. When writing about the garment industry he talks specifically about the “handcraft” industry, and how working there is in many ways even worse than being on a factory floor. The short version is, even if you are working independently you will still have to produce goods at the same prices as large, industrial business do or you will not be able to compete. Since a large company can afford the equipment and infrastructure to produce these items at a fraction of the cost, someone working independently will find it almost impossible to get by alone.

Hence the “precariat” and creative class we have now. This kind of plan of escape, freelancing and artisianal production is not a solution. Marx was quite right on that. It’s as true today as it was in the 19th century. Freelancers and people who work independently have no benefits, paid time off, and generally make even less.

Also, even more absurd is that the title of the bill has nothing to do with its content either. CLOs are in no way “small business.” I’m sure they hope people will hear the title of the bill and stop paying attention.

These bills are named in contradiction to what they actually do. Remember the “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act”?

HR 37 failed to get the 2/3rds majority needed to pass it under the House rule that prevented the bill from being amended.

Democrats Knock Down GOP Bill To Delay Wall Street Reform

We said that at the top of the post.

Alas there was a successful rollback of a different Dodd Frank provision yesterday

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/volcker-criticizes-congress-attempt-to-weaken-dodd-frank-2015-01-08

Supporters of the law have also voiced concerns that Republicans, who now control both the House and Senate, will try targeting Dodd-Frank through spending bills or through other important legislation.

This was the case with the terrorism risk insurance bill that passed the House Wednesday that included a provision on derivatives regulation.

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/house-passes-bill-extending-terrorism-risk-insurance-act-2015-01-07-15911237

The bill also includes a provision that would change part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial law, by prohibiting regulators from imposing margin requirements on non-financial users of derivatives

Will this slip through unnoticed when the Senate moves on the terrorism risk insurance bill?

Although the rollbackof a margin requirement for non financial users appears innocuous enough, the point of the rule (widely debated in the Dodd Frank construction process) was to attempt to redress the mis-pricing of risks of derivatives by requiring all parties pay to play and to reduce the gov’t supplied subsidy to derivatives players. In this case the subsidy appears to accrue to non financial derivatives parties, but actually benefits the derivative seller (i.e banks).

It looks like every House bill will need to include “and Dodd Frank rollback provision” in its title.

Bill passed in the Senate 93-4.

Warren introduced an amendment to strip out the Dodd-Frank provision. Failed.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-politics/wp/2015/01/08/senate-passes-terrorism-insurance-bill-which-is-first-cleared-by-new-congress/