Yves here. This post by Ed Walker provides a detailed description of how badly municipalities have been fleeced when they bought interest rate swaps from Wall Street as part of financings. It isn’t simply that these borrowers were exploited, but that the degree of pilfering was so extreme that the financiers clearly knew they were dealing with rubes and took full advantage of the opportunity.

But what is even more troubling than the fact set here is the failure of the overwhelming majority of abused borrowers to seek to recover their losses. Walker describes that multiple legal approaches lead you to the same general conclusion: the swaps provider, as opposed to the hapless city, should bear the brunt of the losses. So why haven’t cities like Chicago, that have been hit hard by swaps losses, fought back? Walker does not speculate, but in the case of Rahm Emanuel, it’s not hard to imagine that his deep ties to Big Finance are the reason.

By Ed Walker, who writes as masaccio at Firedoglake. You can follow him at Twitter at @MasaccioFDL, and here’s his author page at Firedoglake.

A recent report by Saqib Bhatti of the Roosevelt Institute describes a number of financial deals between Wall Street and municipalities as predatory. Bhatti asserts that these dirty transactions have forced cities and states to cut essential services to pay off the financial sector. On Tuesday, Bhatti’s ReFund America project issued a new report specifically directed at the financial problems of Chicago and calling on the city to fight back in the courts and elsewhere against these deals.

One of the main problems arises from the use of interest rate swaps to create synthetic fixed rate municipal bonds. You’ll get great rates, cities were told, and these interest rate swaps will protect you against interest rate hikes. Risks were downplayed, if they were mentioned at all. The chief of these is the risk of downgrades in credit rating. In those cases, the swap could be cancelled, inflicting massive termination penalties on the city. Other risks include the inability to refinance into a lower interest rate, because the swap runs for a very long term, and payments would eat up any gains. Bhatti says the City of Oakland refinanced one of its bonds, and continues to pay for the swap; he says it’s “like paying for insurance on a car that was sold years ago”.

Another trap was the pension obligation bond. The idea is to borrow the money needed to make up a shortfall in pension payments, with the idea that the pension plan would invest the funds at a higher rate of return than the bond after expenses.

A third trap was Auction Rate Securities. These are short-term securities that have to roll over every month or two. If an investor in ARS wants out, but the city can’t roll the ARS over, the city is stuck with huge interest rate bills. This happened to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which saw interest rates jump from 4.3% to 20% in one week.

The Capital Appreciation Bond works just like a negative amortization home loan. The city doesn’t pay interest or principal for a few years, then starts paying the debt off, with interest on interest. Chicago and the Chicago Public Schools have a bunch of these, with lifetime interest rates ranging from 141% to 459%.

Municipal borrowings have traditionally been paid in full. Even so, far too many cities and school districts have been forced to pay for “credit enhancements” which are just the same as higher interest for no reason related to actual market conditions. On top of that, the two big municipal bond insurers were downgraded because of their exposure to toxic real estate mortgage-backed securities, and in order to avoid getting hammered by accelerated payment provisions in their bonds, cities were forced to find alternatives that were much more expensive.

Finally, the fees paid by municipalities are unusually high. There is no relationship between the services rendered and the fees, according to Bhatti.

The impact of these transactions on cities is horrifying.

For example, the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD) paid $547 million in termination fees to banks on its interest rate swaps in FY 2012. It has been estimated that more than 40 percent of Detroiters’ water bills now go toward paying down these termination fees. Fn. omitted.

In fiscal year 2013, Los Angeles paid $290 million in publicly-disclosed financial fees, while it cut services, including road repairs, by 19%. Other cities have similar horror stories.

The Obama Administration has completely ignored the plight of the citizens of these towns. From the outset Obama decided to help banks and creditors, the people who caused the Great Crash, and to ignore the staggering problems facing debtors. This became certain when the administration refused to support bankruptcy cramdown, one of the few steps that would have actually helped debtors, while inflicting losses on the lenders who made bad loans.

One crucial question is why more of these cities aren’t demanding better treatment. After all, they are run by politicians, who should be able to influence other politicians and other governmental agencies to help with the problems. But there was no pushback in Congress, and the administration did nothing to force financial industry regulators to help or even to investigate, despite reports of rampant fraud in the entire financial sector. Mayors and other local officials have simply refused to take action against the mistreatment of their towns and schools.

Thankfully, cities and school districts, like all parties to contracts, have a number of defenses to such contracts, despite the best efforts of the lawyers who wrote them for their clients in the financial sector. Bhatti mentions Rule G-17 of the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board, which requires banks and others suggesting transactions with public officials to “deal fairly” with them.

According to the MSRB, this means that they “must not misrepresent or omit the facts, risks, potential benefits, or other material information about municipal securities activities undertaken with the municipal issuer.”25 This means that they must ensure that public officials truly understand the risks of the deals they enter into and may not downplay the risks associated with those deals or mislead public officials about the likelihood of such risks materializing.

This suggests a plausible legal approach, either through enforcement actions by the SEC or litigation by cities and other governmental entities.

There are also contractural defenses at the state level. This is from a law journal article by Nancy Kim, Mistakes, Changed Circumstances and Intent.

The most common contract defenses are duress, unconscionability, incapacity, fraud, and the “basic assumption” defenses of mutual mistake, unilateral mistake, impossibility, frustration of purpose and commercial impracticability. Fn omitted.

The latter group is so named because in each case there has been “… a failure of a basic assumption material to the contract.” Let’s see how that would work with swaps. The City of Chicago recently terminated two swaps, after receiving this memorandum analyzing the situation from Swap Financial Group of New Jersey. Chicago entered swaps in 2002 with JPMorgan Chase Bank and Bank of America. The city sold variable interest rate bonds and entered the swaps to create a synthetic fixed rate combination of bond and swaps. The memo says that the combination was expected to deliver a lower interest rate than could have been achieved with a fixed rate bond by an estimated 1.145%. The costs to Chicago included something called a bank enhancement, which was estimated to cost 25 basis points.

As it turned out, the bank enhancement became expensive in the wake of the Great Crash, and the estimated savings over the fixed rate were about $1.4 million per year. Simultaneously, interest rates fell, and the swaps had a negative value of $35.5 million, representing the cost to terminate them. Meanwhile, the bond rating of the city dropped, at least partly due to the Great Crash, which makes it more expensive to refinance than it would have been years ago. The memo goes on to explain that it seems best for the city to terminate the swaps, and Chicago did. That wiped out all gains from the deal, without even taking into account the possibility that it could have refinanced the bonds at the very low fixed rates which have prevailed since the Great Crash.

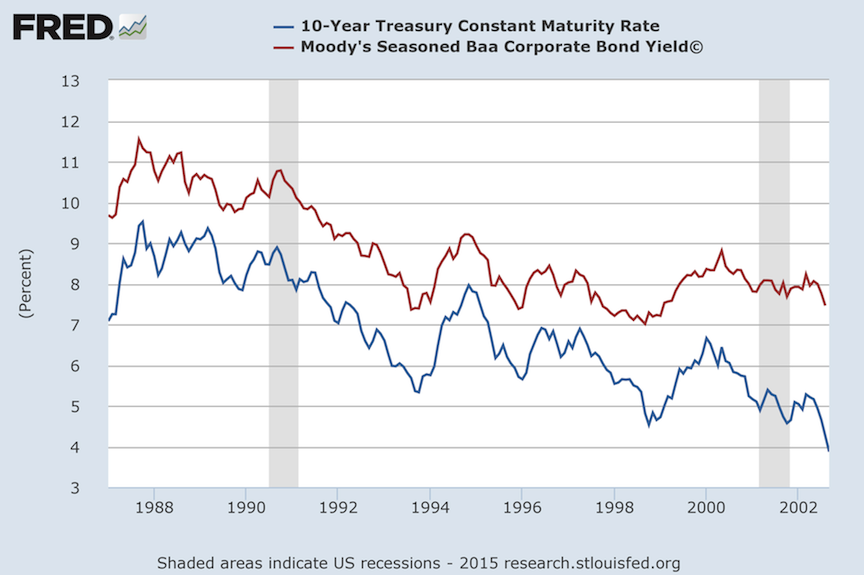

The parties to the swaps, JPM, BAC and Chicago, almost certainly shared the idea that interest rates would act in some historically normal way. That is, they might go up, they might go down, and there is some risk of a significant spike. Here’s a chart showing interest rate trends for the previous 15 years, for Treasuries and Baa rated corporate bonds.

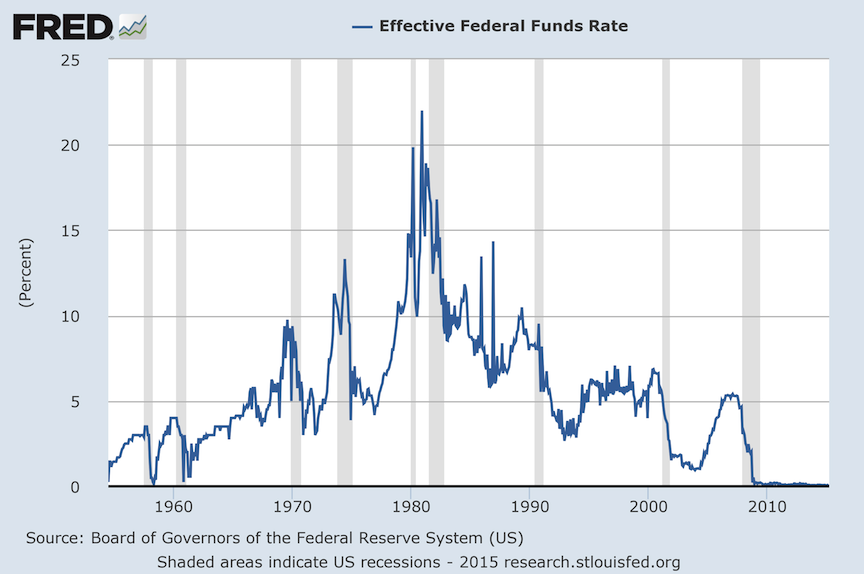

Interest rates are closely tied to the Fed Funds rate, and to people’s expectations about the interest rate policies of the Fed. Here’s a chart showing the Fed Funds rate since 1954.

That low rate beginning with the Great Crash hadn’t been seen in 40 years, and there are no periods when it was even constant for such an extended period. This qualifies as a stark variation from the historical pattern. This isn’t the place for a full legal analysis, but certainly a good case can be made that there has been a mistake in the deep assumptions of the agreements, or that there has been a frustration of purpose by the actions of the Fed in keeping interest rates so low for so long.

Kim cites an article by Richard Posner and Andrew Rosenfield, Impossibility and Related Doctrines in Contract Law: An Economic Analysis, 6 J. Legal Stud. 83, 1977. Posner discusses the application of the doctrine of law and economics to the same kinds of cases. One of his examples is a coal mining company that also makes coal-burning furnaces. It sells the furnaces with a contract to deliver coal at a stated price adjusted by the CPI. The price of coal quadruples, and the company defaults on delivery of the coal. Neither party could have contemplated such a sudden rise in price.

As Posner analyzes the case, the question should be which party is better equipped to deal with such a risk. He concludes that the coal company is best able to deal with the risk by hedging against big changes in the price of coal, because it knows its position in the coal markets. Therefore it should bear the loss. Whatever you think of the theory of law and economics, this seems like good analysis, because the sole purpose of the doctrine, like the facts of a swaps case, is economic efficiency. Kim’s more complex and more traditional analysis seems to support this result.

In the swaps case, it’s obvious that the banks were in the best position to protect against losses on these swaps. They are regular traders in these complex instruments, and have deeper insights into the interest rate markets and the various potential outcomes. Equally important, the banks bear heavy responsibility for the Great Crash. They were in the best position to prevent it. Chicago had no ability to do so.

For a somewhat different take, this paper, dealing with Canadian law, suggests that the appropriate considerations should include the doctrine of unjust enrichment, which is a principle of equity rather than contract law. Put simply, it means that a contract should not be allowed to inflict unreasonable harm “where the contract does not allocate the rick of the mistake to the party who suffers by it.” That certainly seems applicable here.

In each case, besides damages, a plausible remedy would be termination of the swaps without a termination fee. The Fed’s zero-interest rate policy increased the flow of money to the Banks at the expense of taxpayers, which is not a proper purpose and might not have even been considered or intended. The two banks benefited from payments for years, while taking no significant risk, because the Fed has forcibly kept interest rates down. At the same time, Chicago has has suffered revenue losses because of the Great Crash, and has been forced to cut services to its residents. Denying the termination fee prevents unjust enrichment, and results in at least a partial sharing of the risk of a zero-interest rate policy.

Bhatti and others are calling for the City of Chicago to take legal action. It certainly looks like there are grounds for a lawsuit, and if Chicago won’t do it, maybe your mayor should.

In the aging, struggling inner-ring suburb in NEO Ohio where I live, our (part-time) mayor is a (full-time) bond lawyer.

Lawyers in politics seems to be a problem the world over…

http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevekeen/2015/02/19/a-lawyers-mindset-where-an-economists-is-needed/

Sadly, as a property owner in a state with no sales tax, and knowing full well that my local water department, school district, and county government are rubes in the eyes of the Street, I vote against each and every bond measure out of self defense. I am not otherwise obsessively conservative, but when my county, water board, or school board makes a disastrous financial decision, it isn’t they who are on the hook, but I.

…And here, ladies and gentleman, is What’s the Matter with Kansas.

Auditor General Jack Wagner (served his two term limit in Pa. 2004-2012) was the only aggressive statewide financial line officer sounding the alarm while it happened. His audits on swaps in schools, water authorities, transit authorities, bridge authorities, the Pa. turnpike, and municipal general obligation bonds are available in the online archive of the pa auditor General. Needless to say, few of his audits attracted much legislative action despite some fairly clear and common sense recommendations.

It has been estimated that more than 40 percent of Detroiters’ water bills now go toward paying down these termination fees

And yet the pundits claim unions are the cause of all of Detrot’s problems.

Does the much-reviled Michael Moore count as a Pundit or just straight shooter? “Attacks on ‘Roger & Me’ completely miss point of film,” http://www.rogerebert.com/rogers-journal/attacks-on-roger-and-me-completely-miss-point-of-film (Maybe Ebert is just partial to Moore because they, like me, are all a little overweight?)

Effing narrative BS. Amazing what the Pundits get away with, isnt’ it? So glad there are pseudoplaces like Naked Capitalism to retreat to…

Somebody should forward that point about Rahm to Chuy Garcia’s campaign.

Yes. If it’s a choice between a godfather, who is corrupt or just plain financially stupid, and a machine politician then I would go n with the machine politician. Who is kingmaker Bill Ayres supporting? I’m for whoever he’s against.

If someone is a financial controller/treasurer/accountant who manage finance for municipal and that person fail to realise that whilst an interest rate swap will protect the municipal against down-side (rate hike increasing future re-finance rate), it does mean locking in the current interest rate level which means the municipal would not benefit from the up-side (rate plunge which decreases future re-finance rate), we have a deeper problem than Wall Street – clearly the system allow (quite some) incompetent people (at least extremely naive people who believe in free lunch offering by Wall Street bankers) into public offices.

Even though this post talks about floating to fixed swaps, the structure was usually complex and therefore failure prone. For instance, the floating index (Libor) often did not match the index used for the floating rate bond. So you also had what traders call basis risk.

Save us the platitudes. Had risk free rates increased and muni credit spreads tightened you would have wet your pants when wall street was making cash payments to munis. Your prejudice against financial institutions is obviously as strong as David Duke ‘s prejudice.

This looks like a classic case of psychological projection. You are attributing to Walker at attitude that is actually yours, that of prejudice.

If you actually knew anything about derivatives (and I worked extensively with one of the biggest players in the OTC derivatives market when it was getting off the ground, and later, briefly, with their big competitor, Bankers Trust) you would know how damning the remark is about the derivatives being overprice. And they are overpriced in a manner that pretty much only a professional on a trading desk could detect. You have to decompose the structure, which usually means you have to figure out how you’d hedge it (that’s the cost of providing the derivative, the hedge cost) and decompose that into its “greeks” (which if you don’t know what that means, you should just shut up).

A meaningfully overpriced derivative will NEVER NEVER work out for the buyer. My derivatives client could see in the market how Bankers Trust was marking up its trades, and they were horrified: “These deals will just burn their customers and ruin the market.” It may not be an overt disaster as it turned out to be as a result of the dramatic decline in interest rates, but these municipal swaps were almost never simple floaters to fixed. As I mentioned earlier, there was often basis risk (the swaps used Libor when Libor was pretty much never the floating index rate) as well as larding in far more derivates into the structure (more opportunities for ripping the customer off, and more opportunity to for the deal to blow up).

I suggest you read Frank Partnoy’s Fiasco or Satyajit Das’ Traders Guns & Money to understand derivatives sales. Then you might be in a position to have an informed discussion on this topic. All I read here is an industry zealot giving me an ignorant, badly biased response.

I know enough about derivatives to know that if you want to claim a gross mispricing then you look at the forward curve on the day of execution not the outcome of a sample size n<10. Not to mention I recall reading stories of munis doing interest rate swap deals that were not at the money to extract cash flow at t=0. Of course you are likely going to have a cash outflow later. Care to confirm that the deals you cited were at the money for t=0, clearly interest rates moved against the swap but that is not necessarily all of it?

You should also know that a bank that gets paid by a muni ending a swap contract likely put on an equal but opposite swap (plus bid/offer spread – doctors don't help you unless they are getting paid). So whatever you think they made there was some offset.

Like has been said already, hire an advisor that can do pricing and get quotes from multiple competitors.

Apparently you either didn’t read the post, or you think your counterfactual defeats the argument. Let’s try the latter. Suppose interest rates were pushed through the ceiling by the Fed, as Volcker did in the late 70s and then were kept there for 8 years as appears to be the case from the second chart. To make things parallel, let’s further assume JPM and BAC were not properly hedged. Do you think JPM and BAC wouldn’t have tried to back out of the derivatives using the state law arguments I describe? These arguments cut both ways; there’s nothing to wet your pants about.

“let’s further assume JPM and BAC were not properly hedged”. You don’t know what it means to be a market maker do you? No the banks would not have been allowed to get out of the contracts if the market moved against them.

My point is relevant insofar as one recognizes that a properly priced derivative need not be valued at $0 100% of the time for t>0. What matters is the distribution of outcomes is balanced E[X] = 0 + transaction costs (see Coase). Sample size n<10 tells us nothing.

Why can’t the federal reserve provide loans to cities directly?

It seems like this would be a good compromise between the status quo of “All FRB liquidity goes to private banks” and a helicopter drop on citizens.

This is why every state needs its own STATE BANK to lend to its school systems and municipalities.

Interest paid locally is PUBLIC profit, and, presumably, a state bank would be more familiar with the needs and ability to repay of the borrowers. Officers of a state bank would also necessarily be more “accountable” to the public.

This is also why only one state, North Dakota, has a state bank. It is so successful, that several years ago ND residents had the opportunity to abolish property taxes–state bank profits would pick up the slack. Remarkably, the voters declined.

But the fact remains that state banks CAN, and in one instance DO do this.

Which is why the idea never makes it out of the starting gate in the other 49.

Hear! Hear!

That’s one of the recommendations of the ReFund America project. There are political issues, though, that might make it tough.

Sort of a tub-thumping title, no? I mean, the biggest culprit seems to be the idiocy and/or corruption of city budget officials (treasurer? comptroller? anyway…). BofA didn’t force Detroit/Chicago into the swaps, nor does this reflect a national trend — that is to say it’s not representative of a fundamentally corrupt/broken market, ala 2007, in which case the obvious culprit is the entity the created the market, i.e. the Street– so if I were investigating what went wrong here I would be looking for a kickback or an inadequate investment official.

Do you think JPM mentioned the economic impact of the Great Crash as a possible risk? Did anyone do a risk assessment that took into account the risks of down grades or any of the things that have happened since the swaps were issued? The savings are so small that any risk at all tips the balance in favor of either fixed or floating rate bonds. Note that in the memo I mention, the comparison is to a fixed rate bond. The City of Chicago could have issued floating rate bonds and done much better.

that’s why Dante made 9 circles of hell that got worse as they went down.

the city budget officials go to a circle a little higher up than the derivative bankksters.

the thing I wonder about is the mathematicians who concocted these derivatives. they probably have a circle too, maybe doing all the derivative math by hand with pencil and paper and if they make a mistake they get kicked by a demon and a whip comes down so hard on their hand they can’t even write. Shiittt. That scares me just thinking about it.

Do they go in a circle above the budget officials? That’s a philosophical question. I’m not a Dante scholar but I guess you wonder where he would have put them. On the one hand, you can say they’re naive and bumbleheaded about almost everything except math. they just believed what their professors told them, even though it was patently ridiculous. On the other hand, you can say ignorance of moral law is no excuse.

I would put the mathematicians in the highest circle, which may be cuttting them a break they don’t deserve, then the county budget officials below them, and then, in the lowest, the derivative bankster division heads — in a descending depths where D=depth=f(m) where m = malevolent craving for self-enrichment at any cost to society and where D increases as m increases. But I’d still kick everybody’s ass. You can’t kick them all to hell cause they’re already there, by construction. So you have to kick them around hell. Here’s the equation of how the mathematicians get kicked around the center of their circle: kick^2 + whip*2 = 1. hahahahahah.

I worked in investment banks for several years trading swaps (not on interest). The name of the game was getting the dumbest clients to do the biggest deals. The dumber the client, the bigger the margin. Of course, as things got vanilla, you had to start peddling options. Not because they are any good, but because they are opaque and profitable.

But this is ancient news. And I don’t believe that the government employees or elected officials who signed off on these deals were so very naive. They had their own interests, whether political or personal.

Look, if you can’t steal from your country, what is this world coming to!

“Look, if you can’t steal from your countrymen, what is this world coming to!”

Fixed it fer ya. I ain’t laffin.

the cities are incompetent to invest in things they don’t know anything about but put their full trust in the person selling it to them. hopefully some people got voted out as a result.

Not quite correct. It is almost certain that they hired consultants to advise them on these deals. But:

1. Cities won’t have access to experts as good as the Wall Street firms themselves

2. Even if there were some experts like that out there, cities don’t have the ability to assess whether the person is really any good. Same problem as in getting a doctor. You go on proxies, like referrals and bedside manner, that are not very good.

3. The consultants have an incentive to recommend, or at least not recommend against, complex deals. They get paid a lot more to evaluate something complicated. How much could you get paid to say, “Forget about all these swaps. They are bad news. Sure, they save you a few basis points in funding but you are eating way more than that in the hidden risk you are assuming. Odds favor it working against you. Just finance at ten years fixed rate and pay what looks like extra. Having no risk of really costly surprises is worth the extra money.” Not much.

4. Sometimes the consultant is a crony and sure not to be any good. So there is sometime outright corruption in who gets hired, but even when not, there are big obstacles (1-3) to getting good advice.

And let’s not forget that Wall St. does it’s darndest to entertain the purse string holders in the municipal universe. Wine and dine ’em. Provide them with prostitutes and blow. That’s a justified budgetary expense for a Wall St. firm. You get a comptroller or treassurer high and laid and they’ll probably sign just about anything. What else are client relations for?

Apart from that, it’s quite clear that there is a huge quid pro quo game ongoing. Look at David Sirota’s reporting for numerous examples of how cheap it is to make a fortune. Patronage as pension fund management fees and interest rate swaps on municipal bonds.

The sense I get is that there are very few people who are actually in charge, or who are in a position to be in charge who give a damn. Some grafters can be shamed (witness the already wealthy Deval Patrick waving his $7500/day fee to work for Boston 2024 in order to foist the Olympics on an unwilling public after public outrage), but for the most part the name of the game is to grab what you can as fast as you can with no incriminating evidence.

I don’t know how it’s in the US, but in the UK large corporates issuing bonds get derivative advisors and they are rather good. They tend to be butique banks, and given the relatively small (as in more like tens than even hundreds) community of issuers they need to keep their credentials pretty straight. They are, and were as far as I can remember, pretty aggresive on questioning the pricing. Minimum they would do is to ask for splitting the price from mid-swap, and these days also to show CVA/FVA/other price components (it wasn’t alwas like that, granted). When you have a few competitive quotes, that tends to keep the banks (relatively) honest, especially when the advisor then starts asking about assumptions under pricing of some component. Oh, and these butiques tend not to be much in conflict of interest as few have balance sheets to do derivatives.

As quite few of those butique banks are US based, it sounds to me more that the cities wanted to be cheap on advisory fees (including not having an advisor), or hired their cronies to do so, despite lack of expertise (as if we haven’t seen it in other public projects…)

Anyways, few other points.

I doubt that you’d win in court with “cpty will lose if it goes against them, and if it goes against me too much, they will lose too”.

Especially since the cpty in this case would hedge any swap they did with the munies. So yes, the termination fees may be 33m, but out of that the bank would have to pay likely about 30m to terminate their hedge.

Cities could have bought a floor on the floating side of the swap, which would of course make it more expensive for them. Indeed, likely they were offered the floor, since it would mean more revenue for the bank, but as a more expensive option turned it down. Preference of banks in deals like these tended to be be to include some options, since they can be much more profitable (read = much less transparent and easier to blow the premium up) than vanilla interest rates swap. Often you could do this with making the swaps callable for 0 at certain times (giving the cpty right to terminate for no cost at certain times) etc. But as I wrote, it would be all more expensive than a vanilla IRS.

I’m not sure why the cities want to terminate in the first place, and it sounds like a bad advice again. As you say, if they had a fixed rate bond few bps over what they pay on the fixed swap, they would be having more or less the same cashflows. Maybe, just maybe, they could refinance – depending on what terms the bond had. But if they wanted a refinanceable bond, they would have a calleable swap if they were getting any good advice. So likely with the advice they were getting, it would cost them similar amount of money to refi any fixed bond as is the swap.

There are cases of misseling derivatives. Lots of them. Banks salespeople on this were/are very aggressive, and worse than used car salesmen. And their entertainment budgets can easily impress and butter most politicians for any cities smaller than NYC.

But there’s not a few cases of clients feeling that they are smart enough to do it and get badly burned. I’d hesitate to judge one way or another unless I saw the whole picture.

Large corporates are in a different universe of sophistication compared to US municipal borrowers. They run large treasuries and typically deal in multiple currencies. This isn’t apples and oranges, it’s apples and stinky fruit.

‘The banks bear heavy responsibility for the Great Crash. They were in the best position to prevent it.’

Banks will never prevent crashes. They enable bubbles, and in turn, bubbles cause crashes.

What we shouldn’t do is incentivize bad behavior by bailing out TBTF banks. Nor should we allow a bank cartel (the Federal Reserve) to centrally plan interest rates for the benefit of banks.

I would add, not only swaps.

Wall Street used the global reserve currency status of the dollar to get rich at the expense of nations.

Not to be mister one-note-tune — but — lack of unions is exactly the problem. Dean of the Washington press corps, David Broder, told a young journalist that when he came to Washington 50 years earlier the lobbyists were all union. The reason the politicians are so lazy about undoing all these rip offs is that there is nobody minding all the many, many stores for the average person.

There are two set of ideas in this post. Some arguments are related to the process by which the bonds were sold. Some relate to violent changes of circumstances. The rights of the City due to the latter are completely independent of the former.

Yes, that’s logical. But yours is also something of a non sequitor argument. The argument being made is that munies that borrowed money at slightly lower cost, but more risk, were ill-advised going into 2007-09. And Yves peppered the conversation by laying out the reasons it is difficult for a munie to play counterparty at the Wall Street casino. Watching hundreds of millions (billions?) in munie defaults in recent years, I am left to wonder, “who won?”

I guess one of the great unknowns is ZIRP–was this policy anticipated–ie Paulson’s tanks in the streets, etc.

All the guesses were to the upside I think as the economy was in one of it’s perennial overdrives, vis a vis interest rate moves circa 2006. Not to ameliorate the condign tools who managed these complex financial instruments.

A line from my upcoming sci-fi film, SYMBIONT, wherein Detroit is transformed from The Motor City to The Breadbasket of America.

Yes, I know it’s not quite municipal bonds, but have you ever tried explaining credit default swaps to an 18- to 25-year old?

COOK: Saddam Hussein, in his wildest wet dreams, couldn’t IMAGINE weapons of mass destruction as lethal as municipal bonds.

Interesting parallel from France:

“The study offers empirical evidence that politicians routinely used high-risk loans on purpose, for political gain, in spite of the risks. Furthermore, the strategy worked: Toxic loans helped incumbent mayors get reelected.”

http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/7692.html