Yves here. Wolf was early to point out the disconnect between declining rig counts, which the mainstream media has touted as proof that the oil glut was about to end, and rising production. That pattern has not abated.

By Wolf Richter, a San Francisco based executive, entrepreneur, start up specialist, and author, with extensive international work experience. Originally published at Wolf Street.

The price of oil did today what it has been doing for a while: it waits for a trigger and plunges. As I’m writing this, West Texas Intermediate is down 4.4%, trading at $44.99 a barrel, less than a measly buck away from this oil bust’s January low. It’s down over 20% from the peak of the most recent sucker rally.

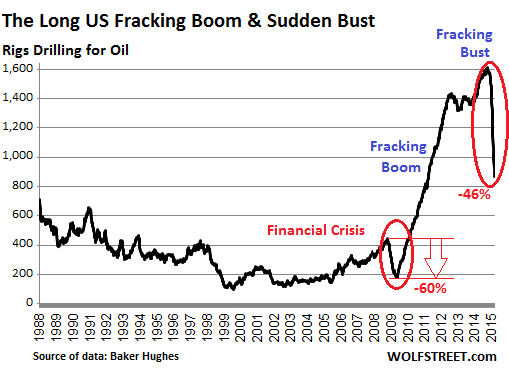

US oil drillers have been responding by slashing capital expenditures, including drilling, in a deceptively brutal manner. In the latest week, drillers idled 56 rigs that were classified as drilling for oil, according to Baker Hughes. Only 866 rigs were still active, down 46.2% from October, when they’d peaked at 1,609. In the 22 weeks since, drillers have taken out 743 rigs, the most dizzying cliff dive in the data series, and probably in history:

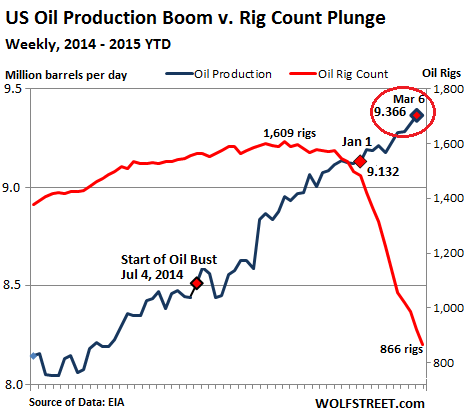

You’d think this sort of plunge in drilling activity would curtail production. Eventually it might. But for now, the industry has focused on efficiencies, improved drilling technologies, and the most productive plays. Drillers are trying to raise production but with less money so that they can meet their debt payments. Thousands of wells have been drilled recently but haven’t been completed and aren’t yet producing. This is the “fracklog,” a phenomenon that has been dogging natural gas for years.

So US oil production hit another record of 9.366 million barrels per day for the week ended March 6, according to the Energy Information Administration’s latest estimate. This chart shows how the rig count (red) has plunged while production (black) continues to soar:

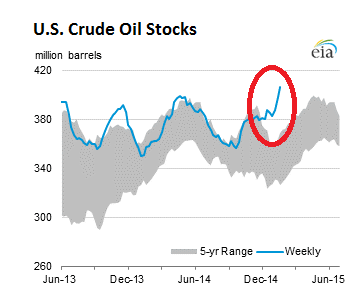

But demand is not living up to the level of production and imports. As an inevitable result, US crude oil inventories are piling up. Excluding the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, crude oil stocks, according to the EIA, rose by 4.5 million barrels in the latest reporting week, to a record 448.9 million barrels. A more modest rise than in prior weeks, but the ninth week in a row of increases. Crude oil stocks are now 78.9 million barrels, or 21.3%, higher than at this time last year. Note the beautiful spike:

So when is US storage capacity going to be full? That event would cause all sorts of havoc in the oil markets, including a terrible plunge in price. With no place to put their oil, some production companies would have to turn off the tap and leave the oil in the ground. That would bring production down in a hurry, but it would add to the pent-up supply, the “fracklog,” thus dragging out the bust even further.

How likely is this scenario?

Last week, the EIA released estimates that crude oil stocks nationwide, as of on February 20, were at 60% of “working storage capacity,” up from 48% last year at that time. In critical Cushing, Oklahoma, which accounts for 14% of the national total and is the delivery point for WTI futures contracts, storage facilities were 67% full.

Given a storage capacity of 521 million barrels, if weekly increases amount to an average of 5 million barrels going forward, it would take about 3 months to fill the remaining capacity. Cushing would be full sooner, which would pose its own set of problems.

But we’re not biting our nails just yet. The largest US refinery strike in 30 years that impacted 12 refineries and a fifth of US refining capacity appears to be settled. A tentative agreement has been reached between the United Steelworkers union and oil companies. Once these refineries are fully operational again, more crude will head their way. The driving season will start soon. SUVs and pickups and even fuel misers have a prodigious appetite collectively and can burn through a lot of gasoline in a hurry. And imports could be throttled back further.

So there is a very good chance that storage capacity will disappear as a death trap for the price of oil this year. But US oil production is likely to continue to rise, leaving the industry to face an even bigger oil glut and even more price mayhem next year. Yet production won’t start declining until the money runs out.

Some smaller oil and gas companies are already running out of money. For them, “restructuring” and “bankruptcy” are suddenly the operative terms. Read… “Default Monday”: Oil & Gas Companies Face Their Creditors

they’re already holding off on fracking, not so much due to lack of storage, but to wait for higher prices…ie, North Dakota production declined by approximately 37,000 barrels per day to 1.19 million barrels per day in January while the number of wells waiting to be fracked rose to 825…all that represents hidden inventory waiting to be added to domestic supply if prices rise…

Dont worry it will start going down, always lag between rigs declining and production. And oil stocks dont necessarily have to do with US production as we’re still importing 10 mbd or so. Add to that, month to month oil numbers are to say the least no rigorous.

yes, due to oil being put in storage due to the contango trade, oil imports have only fallen 1.2% YoY while domestic production is up over 15%..

I don’t understand how this paragraph relates to storage capacity. Can someone explain? Thanks.

oil not being refined must be stored

Right. So the resumption of refining will alleviate the storage crunch. Doesn’t that undercut the thrust of the article, or am I missing something?

a bit…as i noted earlier, a lot of oil is being stored under contract to deliver it at a higher price later…we are now importing oil not to run cars and heat homes, but to keep the derivatives casino running…

rjs,

The contango is real but the contango play is slowing globally–as an example, 30 tankers or more were chartered for oil storage not long ago and all but 12 have been released. Gotta sidestep this fixation on financial doings alone. The US is importing crude oil just as it has been for years, though the amount has decreased (not increased) in the past few months. Contango is not driving US imports of crude.

Start here: Who in the US imports crude oil?

Refineries.

What do they do with it?

They break down the molecules that make up crude and sort the fragments out into groupings we call gasoline and diesel and jet fuel and some remainders that have their uses too.

Do US refineries produce products for the US market alone?

No. About three million barrels a day of crude are refined into products for export to Central and South America, Canada, and Mexico. This earns money for the refineries.

Can any refinery refine any quality of oil? (“Quality of oil” [not an industry term] would be defined, as a first approximation, on the basis of how viscous it is and how much sulfur it contains.)

No. A given refinery is optimized for a particular range of oil quality, out of the wide variety offered by producers, and will blend various crudes to produce the oil it needs. (It could handle qualities outside its optimum range but would lose efficiency–and money–and eventually mess up the works.) Most refineries in the Midwest and on the Gulf Coast are optimized for a middle-range quality oil.

Is the oil building up in storage right now not useful to refineries?

It is useful for blending but there’s too much of it right now. Much of it is from the shales, and is high-quality, low-viscosity crude, and there is much more of it available than the lower-quality, high-viscosity crude it would be blended with.

Where does that high-viscosity crude come from, then? Is it from the shales too?

It does not come from the shales, but from various other sources like conventional fields on land and in the Gulf of Mexico. The US produces some and some is imported, especially from Canada, Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico. They’re all producing pretty much flat out, or would be if the oil industries in Mexico and Venezuela weren’t in such a ghastly state.

Why don’t the shale producers slow production then?

You go tell them to, and I’ll watch. They have been cutting back on drilling and on bringing recent wells into production, but that’s because the oil price has fallen too low for them to keep all their operations going. Producing oil and selling it brings in the money to pay your bills and make payments on debt so some production is going on in spite of so much being in storage. Some companies are trying to survive right now.

So, what’s the take-away here?

There’s too much of the stuff the shales produce for the refineries to use it all. They would blend it with the higher-viscosity stuff but there’s only so much of that available. They do use what they can get, as they have been doing right along. US imports of crude oil aren’t suddenly higher than they have been in the past–they’re lower if anything–because of the current contango situation. That situation is being taken advantage of by some, sure, but it is not much of an influence on the amount of crude the US imports.

You can’t just turn a refinery on and off, and refineries depend on cash flow just as the rest of the oil patch does. The refineries have been importing crude right along because they need to keep running. When the contango goes away they’ll go right on importing crude.

Is Alberta Tar included among the more viscous stuff which could be blended with the less viscous stuff like Bakken . . . to create a mid-viscous mixture? Is that part of the reason for the desire to get Keystone XL North built? To get enough

Alberta sand-tar to mix with all the Bakken gassy oil?

we are exporting Bakken crude to Alberta where it is mixed with bitumen, creating dilbit, ie, diluted bitumen…

Oh. I had thought that the Alberta tar was mixed with benzene among other selected chemicals to make it into diltbitar. Was I wrong about that? Is it mixed with crude Bakken?

Synapsid, look at Wolf’s EIA chart of crude oil stocks above; that massive inventory build didnt start until October, after oil prices dropped and the spread widened…all the factors you cite are true, but they have been factors for years, and inventory stayed in a normal range…but not until the spread was wide enough to make oil storage contango profitable did inventories spike…

Hi rjs.

October is when the WTI spot price went from dropping to plunging, as more and more crude from the shales flooded in; that helped to open the spread. Output was climbing in the Bakken and that crude went both East and down to Cushing OK, where it began to back up again because crudes from both Eagle Ford and the Permian Basin were causing a big backup at Houston, whose refineries could take less from Cushing as a result. Piipelines being built to get crude from the Permian Basin to Houston have been coming on line, and contributing to more oil heading to refineries in the area. The crude that couldn’t be handled began going into storage and the contango play became a viable strategy as the spread widened.

The refineries have gone on doing what they do, and that includes importing crude to help them make up the blends they need, as always. US refineries do the job for a lot of the countries in the Americas and exports of refined products have increased.

That passage is a list of reasons one might expect not to see storage max out this year, which is a reasonable hedge to add on a predictive piece.

Richter ended the article saying the storage situation may not be likely to go critical THIS year. The thrust of the article is that this is a looming problem that may go critical soon after.

Might the Obama administration increase the size of the strategic petroleum reserve as a corporate bail out on falling prices?

The total SPR capacity is 727m barrels. As of March 6, total storage is 691m barrels.

I’m sure our kids will be grateful for that. The Vanuatuans’ monster storm will be coming our way soon..,

The hopeful fallout of this driving season oil burnoff would be such demand-beyond-supply for oil that KSA and the Lesser Gulfies would be able to raise prices back to over a hundred dollars a barrel and force more millions of noo-voe poor ex consumers down out the bottom of the oil market to crash oil prices again. Could it work that way? Or must oil prices stay low enough long enough to exterminate unconventional production once and for all before the petrokingdoms can re-raise the price as much as they like? If so, can a movement-load of people do something to keep demand down to keep price down? Or will eleventeen thousand million hundred happy drivers swamp any conservation effect that a movement load of motivated conservers could have?

I hear you. At least they’re not flying?