By Jérémie Cohen-Setton is a PhD candidate in Economics at U.C. Berkeley and a summer associate intern at Goldman Sachs Global Economic Research. Originally published at Breugel.

What’s at stake: The negative yields observed on some government and corporate bonds, as well as the recent move into further negative territory of monetary policy rates, are shaking our understanding of the ZLB constraint. This blogs review summarizes the recent debates on the binding nature of the zero lower bound. Next week, we’ll look at the implications of negative interest rates for financial stability.

Matthew Yglesias writes that something really weird is happening in Europe. Interest rates on a range of debt — mostly government bonds from countries like Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany but also corporate bonds from Nestlé and, briefly, Shell — have gone negative. And not just negative in fancy inflation-adjusted terms like US government debt. It’s just negative. As in you give the German government some euros, and over time the German government gives you back less money than you gave it.

Evan Soltas writes that economists had believed that it was effectively impossible for nominal interest rates to fall below zero. Hence the idea of the “zero lower bound.” Well, so much for that theory. Interest rates are going negative all around the world. And not by small amounts, either. $1.9 trillion dollars of European debt now carries negative nominal yields, and the overnight interest rate in Swiss franc is around -1 percent annually.

Gavyn Davies writes that an unprecedented experiment in monetary policy is underway in two small countries in Europe. By pushing policy interest rates more deeply into negative territory than ever seen before, the Swiss and Danish central banks are testing where the effective lower bound on interest rates really lies. Denmark and Switzerland are clearly both special cases, because they have been subject to enormous upward pressure on their exchange rates. However, if they prove that central banks can force short term interest rates deep into negative territory, this would challenge the almost universal belief among economists that interest rates are subject to a ZLB.

Paper Currency and the Zlb Constraint

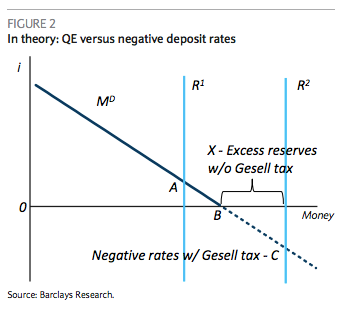

Miles Kimball writes that paper currency (and coins) guarantee a zero nominal rate of return, apart from storage costs, which are relatively small. It is then difficult for central banks to reduce their target interest rates below the rate of return on paper currency storage, which is not far below zero. This limitation on central bank target interest rates is called the “zero lower bound.” Because the zero lower bound is a consequence of how monetary systems handle paper currency, it is possible to eliminate the zero lower bound by alternative paper currency policies.

JP Koning writes that there are a number of carrying costs on cash holdings, including storage fees, insurance, handling, and transportation costs. This means that a central bank can safely reduce interest rates a few dozen basis points below zero before flight into cash begins. The lower bound isn’t a zero bound, but a -0.5% bound (or thereabouts).

Gavyn Davies writes that in the past, economists have always assumed that the convenience yield on bank deposits is extremely small, so there would be a stampede into cash, led by the banks themselves, if the yield on deposits at the central bank went even slightly negative. But no one really knows whether that is true. In the long term, new businesses would appear, helping the private sector to handle and store cash cheaply and efficiently, but this may not happen quickly.

Reviewing the Convenience Yield on Deposits and Bonds

Evan Soltas writes that if people aren’t converting deposits to currency, one explanation is that it’s just expensive to carry or to store any significant amount of it. Therefore, the true lower bound is some negative number: zero minus the cost of currency storage. How much is that convenience worth? It seems like a hard question, but we have a decent proxy for that: credit card fees, counting both those to merchants and to cardholders. That’s because the credit-card company is making exactly the same calculus as we are trying to make – how much can we charge before we make people indifferent between currency and credit cards? The data here suggest a conservative estimate is 2 percent annually.

Barclays (HT FT Alphaville) writes currency hidden under a mattress is useful for small transactions in your local market (the local café or store). However, it is of little use for large or distant transactions since armored trucks are neither cheap nor convenient. Internet transactions are an increasingly large share of both retail and business-to-business transactions, and bank transfers are an even larger share. Aside from the costs of transferring cash, both consumers and businesses derive utility from the convenience of book-entry (electronic) transactions.

Barclays writes that the value of that convenience likely forms the negative lower bound. Credit and debit card interchange fees, the fee card companies charge merchants for transactions, are a measure of how much that transaction utility is worth to both consumers and businesses that accept card payment. Until recent moves to regulate interchange fees, debit card interchange fees were approximately 1-3% of transaction value, depending on the card and the merchant. Credit cards, which remain unregulated, still command fees in that range. Coincidentally, the ECB has calculated that the social welfare value of transactions is 2.3%. If these rates represent an accurate measure of the value of transaction utility, they suggest that the negative lower bound for interest rates likely is considerably lower than the –75bp in Sweden and Switzerland.

Paul Krugman writes that the medium of exchange utility is irrelevant. In normal times, once interest rates on safe assets are zero or lower, liquidity has no opportunity cost; people will saturate themselves with it. That’s why we call it a liquidity trap! And what this means is that the marginal dollar of money holdings is being held solely as a store of value — the medium of exchange utility is irrelevant. Paul Krugman writes that when central banks push interest rates on government debt below zero, the effective lower bound is the return on cash held by people who would otherwise be holding that government debt — not people looking to expand their checking accounts. So the liquidity advantages of bank deposits over cash in a vault are pretty much irrelevant. It’s all about the cost of storage.

JP Koning writes that Krugman is assuming that liquidity is a homogeneous good. It could very well be that “different goods are differently liquid,” as Steve Roth once eloquently said. The idea here is that the sort of conveniences provided by central bank reserves are different from those provided by other liquid fixed income products like deposits, notes, and Nestle bonds. If so, then investors can be saturated with the sort of liquidity services provided by reserves (as they are now), but not saturated by the particular liquidity services provided by Nestle bonds and other fixed income products. Assuming that Nestle bonds are differently liquid than central bank francs, say because they play a special roll as collateral, then Soltas isn’t out of line. Once investors have reached the saturation point in terms of central bank deposits, the effective lower bound to the Nestle bond isn’t just a function of the cost of storing Swiss paper money, but also its unique conveniences. Koning quotes Michael Woodford’s Jackson Hole paper: “one might suppose that Treasuries supply a convenience yield of a different sort than is provided by bank reserves, so that the fact that the liquidity premium for bank reserves has fallen to zero would not necessarily imply that there could not still be a positive safety premium for Treasuries”.

A Bit of History of Thought on Negative Interest Rates

Brad Delong writes that the idea of making money earn a negative return is not entirely new. In the late 19th century, the German economist Silvio Gesell argued for a tax on holding money. He was concerned that during times of financial stress, people hoard money rather than lend it.

David Kehoane writes that for those not familiar with the 19th century idea of a Gesell tax, it’s basically a stamp tax on money that acts as a negative interest rate. The idea being that in order to be legal tender notes would have to bear an annual/ monthly stamp provided by the government — and for which the government would charge a fee.

Brad Delong writes that this is not an obscure idea. Silvio Gesell is the topic of part VI of chapter 23 of Keynes’s flagship work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. And it’s not just Keynes in his flagship work. There are 55,000 google hits for “Silvio Gesell.” Patinkin (1993) reports that Irving Fisher advocated Gesell-based “velocity control” in his 1932 Booms and Depressions. Nobel prize-winning Maurice Allais was an advocate as well. Gerardo della Paolera and Alan Taylor are Gesell’s biggest boosters today in their book Straining at the Anchor: The Argentine Currency Board and the Search for Macroeconomic Stability, 1880-1935, a University of Chicago Press book that is part of the NBER’s series on “long term factors in economic development.” Willem H. Buiter and Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou writing in the Economic Journal in 2003: “Overcoming the Zero Bound on Nominal Interest Rates with Negative Interest on Currency: Gesell’s Solution.”

JP Koning writes that a central banker can safely guides rates to a much more negative rate than before, say to -2.5% rather than just -0.5%, by varying the conversion rate between low denomination notes/electronic currency and large denomination notes. Central banks currently allow free conversion between deposits, low value notes, and high value denominations. The idea here is to keep the conversion window open, but levy a fee, say three cents on the dollar, on anyone who wants to convert either deposits or low denomination notes into high denomination notes. Conversion between low value notes and deposits remains free of charge. This method is akin to Miles Kimball‘s crawling peg, except that the conversion penalty is set on high denomination notes only, not cash in general.

No mention of money laundering restrictions which add to the cost of transferring large amounts of currency. Which isn’t to say that banks can’t do it, but they certainly adds to the costs for non-bank players.

Money laundering is very profitable for banks, hence why they are very willing to break the law to do it.

How would money laundering restrictions prevent me from simply withdrawing my money as cash.

It might make it a bit inconvenient, with some paperwork but it couldn’t stop me.

What am I missing here?

ian–

You have to look at the whole picture.

In the US holding cash is by law prima facie evidence of drug dealing. The amount varies (I have heard of seizures of as little as $3000, and plainly bogus seizures of even less) but typically $10 000 is the threshold. The state seizes your money and the burden of proof is on you to prove the money did not come to you from selling drugs. Unconstitutional? Surely!–but that no longer matters. Take it to court and see.

So one of the costs of holding cash is the cost of hiding that cash. Specifically, hiding it from the law. The costs of holding cash in today’s article are grossly underestimated.

–Gaianne

The difficulty isn’t so much withdrawing it as it is spending it…any large ($10k or more) cash transaction requires special paperwork that many people don’t want to bother with so they’ll simply decline…It actually IS difficult to buy a car with cash. And as Gaianne pointed out large amounts of cash are considered evidence of drug trafficking….Spending $5k on lawyers to get your seized $50k back is a pretty big bite out of your savings.

That’s a lot of negativity! Wow.

Profeser Tremens writes that interest rates are not absolutes like gravity and Newtonian time, that have an existence independent of human behavior, but relative quantities in their entirety and only have a reality in relation to other rates of interest. If you’re getting -2% and everybody else is getting -3%, you’re really getting +1%. The negative sign is just an arbitrary mathematical symbol, the real world math is all relative and therefore the algebraic sign of the interest rate is always a distribution, across the financial population, of plus signs and minus signs. There is nothing all that remarkable about the average of the absolute level since the average of the distribution, when normalized at a zero mean, is zero. What about converting to cash and burying your money in a hole to get +2%? It’s not worth it for most people. The big money would pay more to protect their hole than they’d pay in relative interest. And since loans create deposits, banks won’t be cash constrained in lending even if some people put their money in holes. What if Google says they’ll put your money on a server for -0.5%. Innovation! That means less money is available to lend and the rate will go up! And I guess the minus signs won’t last all that long since banks won’t want Google to have all the money in the world. haha

Holy Career Path, craazyman! When did you get the PR job at the New Yawk Fed???

Is that what they’d say?

in that case, I take it all back! I just made it up! It’s wrong! Fugghetaboudit (that’s how we tawk in New YAWK)!

Yeah well there will always be someone with their cash stuffed in the wall accruing 0%, so anyone enjoying a -2% cashburn may have the satisfaction of knowing someone has a brighter flame but the fact is that -2% will always be on the wrong side of 0.

A theoretical case for doing nothing being the best course of action.

Well … with an excel spreadsheet … I can prove anything.

I would rather see the federal govt provide enough money to satisfy savings needs and discourage people from reaching for yield in risky products. They could do this by guaranteeing a 2-3% positive interest rate on money market funds similar to advantages they give to large banks. This would also help keep money market funds out of tri-party repo transactions and put those sort of speculative investments into the realm of people who want to make them and take the risks.

how about the fact that in general notes in circulation are fraction of deposits? like 1/5 for usd, and about 1/20 for eur.

so even if everyone wanted to have cash only, it would be impossible, no matter the deposit rate.

Negative interest rates make sense in a deflationary spiral. If deflation is 3% per year, an interest rate of -1% gives a +2% return.

Knowing how clueless central bank economists really are, they are precipitating a deflationary spiral. What they say ie: we are afraid of deflation and will do whatever it takes to not let that happen, is the exact opposite of what will happen.

Like a driver faced with an unfolding emergency ahead, instead of looking for where to go, and having the steering wheel follow the eyes and avoid a crash, central bank’s eyes are fixated on deflation and they will crash right through it.

The globalization buzzards are coming home to roost. When Bernanke was singing the praises of low inflation ten years ago, due to Chinese slave labor and the resultant destruction of manufacturing industries in North America and Europe, he was cheered as a wise visionary. Now we are screwed. The Chinese are still slave labor, and slaves don’t have money to buy their own production.

There has been a huge increase in the supply of labor, and no increase in customers. That spells deflation.

Why should “money” earn “money” i.e., interest? – apparently we can create all the money we want and cats and dogs aren’t mating yet….

Interest, inflation, deflation.

Funny how the decline in wages, i.e., isn’t termed “deflation” – – and isn’t discussed. Deflation…so, so, sooooo bad…except when it happens to laborers…..

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2013/09/10/some-95-of-2009-2012-income-gains-went-to-wealthiest-1/

Funny how making all the money we want doesn’t really seem to get things going.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/MULT

http://prospect.org/article/40-year-slump

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/10/09/for-most-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/

http://www.dollarsandsense.org/archives/2014/1114sherman.html

f the distribution of income had remained roughly the same over the last forty years, then the fact that per capita GDP nearly doubled would mean that everyone’s income had nearly doubled. That’s not what happened. Instead, those at the top of the income distribution have vastly more income than 40 years ago while those at the bottom have less. The real income of a household at the 20th percentile (above 20% of all households in the income ranking) has scarcely budged since 1974—it was $20,000 and change then and is $20,000 and change now. For those below the 20th percentile, real income has fallen. The entire bottom 80% of households ranked by income now gets only 49% of the national pie, down from 57% in 1974. That means that the top 20% has gone from 43% to 51% of total income. Even within the top 20%, the distribution skews upward. Most of the income gains of the top 20% are concentrated in the top 5%; most of the gains of the top 5% are concentrated in the top 1%; most of the gains in the top 1% are concentrated in the top 0.1%.

Wouldn’t negative rates imply some sort of deflation?

I feel crushed.

I would speculate only if “everyone” is exposed to negative interest which i doubt is the case?

Yes, and why the officialdom thinks this will lead to more spending is beyond me. If you are a retail person, you keep cash at home with all the attendant risks and delay spending, since stuff will be cheaper later. Institutional investors shift to currencies with positive yields and take their FX chances.

Negative interest rates would definitely make the heads of deficit hawks explode… How can you argue against government borrowing in a world of negative interest rates? The deficit keeps shrinking no matter how much we borrow… (Of course, things would change at some point, but still – let’s borrow from European banks at negative interest rates and start infrastructure repairs!)

How do you explain the phenomenon of negative interest-rate bonds in the context of the fact that a bond’s value and coupon reflect the issuer’s solvency? What possible justification would there be to take the risk of investing in a Nestle bond, and paying for that? Not only once but twice; if interest rates go up, the bond price will go down. That’s a guaranteed loser. Not only that, but once you chase the good money out of safer bonds, it’ll go after even riskier mechanisms for yield–speculation on equities, implausible venture capital folderol, tulip futures.

I can think of one: you have lost confidence in the banking system and expect anything from 10% to 50%, or even 90% of the money on your deposits to disappear in a “bail-in” of the bank, or disappear altogether in a bankruptcy uncovered by state guarantee funds.

From that perspective, a slightly negative interest rate on a non-financial institution might not be such a bad deal (cannot be bailed in, is not subject to bank bankruptcy).

If the banks don’t want my money (deposit interest near zero) and governments don’t want my money (bond interest zero and below) why should I want it?

“They can do anything we can’t stop them from doing.” Catch-22 Heller

why should I want it?

To buy stuff?

If the banks don’t want my money (deposit interest near zero)

Don’t confuse Banks not wanting to pay you interest on your money with Banks not wanting your money. They all want all your money –and more.

All Banks are doing is (allegedly) insuring that your deposit will be available at some point in the future at face value, as limited by FDIC insurance levels, less the difference between the face value at deposit vs at redemption plus “interest” (in the case of negative interest) .

That’s the cost of the “insurance policy” to provide you protection and portability! The peace of mind that Rats in the wall aren’t shredding your stashed Dollars to make a nest and the convenience and security of being able to write a check, execute wire transfer and/or keep credit card accounts funded.

You can consider a Dollar as a zero coupon bond with no Love. No discount on face value when you acquire it and no juice when redeeming it. :-(

Eventually, governments are going to catch on that, in principle, cash doesn’t even have to return 0.

You can just issue “2016 dollars” next year, and declare “2015 dollars” no longer legal currency. Everyone has to schlep to the bank and trade them in. The exchange rate can be less than 0% interest, it can be whatever you, the government, like. The exchange rate doesn’t even have to be constant with exchange size.

(And I think it hardly needs mentioning that unconvertible, all-digital money administered by a Central Bank can have any interest rate, negative or positive; zero is truly non-special.)

The constraints against doing this are not economic, but political. The ZLB exists in the polity’s head, not in any sort of “economic reality”.

Don’t give them any ideas!! Sheesh!! Actually what you are describing sort of already happens in an inflationary environment, no?

In other words, if my great grandfather buried $500 behind the house back in 1915, my digging it up tomorrow won’t give me the spending power that money had a century ago– even though the “worth” is still $500, right?

It would depend on what he buried – if they were mint condition gold double eagles…

Fine. They can all go and buy negative yielding bonds, and pay to deposit with the SNB, and develop any academic theory they want. I’ll keep cash in the mattress earning zero.

Great post.

A most trivial correction: the Google hit count on “Silvio Gesell” says 128,000 (today), but that hit count is always wrong, and usually exaggerated by a factor of 100 or more. If you click through to the last search page, you’ll see that there are actually about 800 hits. Not that it matters in the slightest for the arguments here, but it’s a common mistake (promoted by Google) that the hit count actually reports the number of pages with that string.

Yet another stage of the 99% towel wringing. Force people to spend the little money they have on crap in place of the security provided by capital accumulation. Which, in addition, denies them any future capacity of defining their own economic destinies (i.e. opening a business, etc.) without becoming indebted further. This has been done many times before by powerful interests wishing to subordinate populations with rents and debt. The Catholic Irish were removed of the capacity to accumulate capital by English law as a way to deny them a capacity to compete with their Anglo/Irish Protestant tenets (see “The Invention of the White Race Vol. I). It must be a government obligation to spend the capital for further investment and improvements in productivity, not the populace.

How many camels will fit on the head of a pin? Erudite men all, debating something so absurd as to be farcical. The bank debt money creation system in its death throes…and all gathered around to try and chronicle its last convulsions. Where are Lewis Caroll and Jonathan Swift when you need them?

“Camels fit on the head of a pin?” Very interesting conflation: of the camel fitting through the eye of the needle, and the mockery of medieval scholastic debate, as regarding nothing more consequential than the number of angels that can dance on the head of a pin.

Yet what would you have us do? St. Augustine knew that the world he grew up in was beginning to collapse, but he was constrained to discuss it in the terms of late classical antiquity that he and his contemporaries understood. We can have hopes and fears about what may come, but anything we say about that will be either dystopian or utopian creative fiction. This world we currently inhabit may indeed be in its “death throes,” but no one knows the hour of its collapse!

Fiat currency flat lined around 2008 and has been on life support since then. Look at any current yield chart and see for yourself, it is done. The only thing that backs fiat in the first place is faith and trust: Public faith that a currency will retain its purchasing power, which it certainly has not, and trust a currency will not be over printed into oblivion, which is what has happened: Having a discussion about negative yields signal the end result of a fractured monetary system which has failed.

Even a couple of generations ago, during the Regan/Volker era, people would have been running for the hills with amount of currency debauchery that has taken place but today people on the whole calmly sit here and discuss negative interest rates and wait to be spoon fed a solution which simply does not exist.

Take your fiat out of the system while you still can. Invest in land, food, precious metals or any commodity other than a fiduciary media whose time line has ended. This should not be viewed as a solution but as wealth preservation goal for the 21st century.

Huh?

First, if people distrusted currency, they’d be holding hard assets, not accepting super low bond yields.

Second, fiat always has value because it is used to pay taxes.

Third, currencies were devalued regularly under a gold standard.

Fourth, you need to issue more currency when you have mild inflation, which is the least undesirable price pattern to have. Otherwise you get economic contraction. Steady and low inflation can be priced into the value of long-term assets, so investors will do relatively well. Look at what you goldbugs get with your prized zero inflation: zero yield on short-term assets. No income for savers. How is that working out?