By Rajiv Sethi, Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University. Cross posted from his blog.

The real money, peer-to-peer prediction market PredictIt is up and running in the United States. Modeled after the pioneering Iowa Electronic Markets, it offers a platform for the trading of futures contracts with binary payoffs contingent on the realization of specified events.

There are many similarities to the Iowa markets: the exchange has been launched by an educational institution (New Zealand’s Victoria University), is offered as an experimental research facility rather than an investment market, operates legally in the US under a no-action letter from the CFTC, and limits both the number of traders per contract and account size. While there are no fees for depositing funds or entering positions, the exchange takes a 10% cut when positions are closed out at a profit and charges a 5% processing fee for withdrawals. (IEM charges no fees whatsoever.)

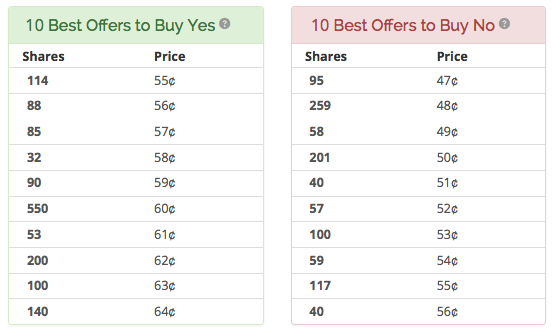

While still in beta and ironing out some software glitches, trading is already quite heavy with bid-ask spreads down to a penny or two in some contracts referencing the 2016 elections. Trading occurs via a continuous double auction, but the presentation of the order book is non-standard. Here, for instance, is the current book for a contract that pays off if the Democratic nominee wins the 2016 presidential election:

To translate this to the more familiar order book representation, read the left column as the ask side and subtract the prices in the right column from 100 to get the bid side.

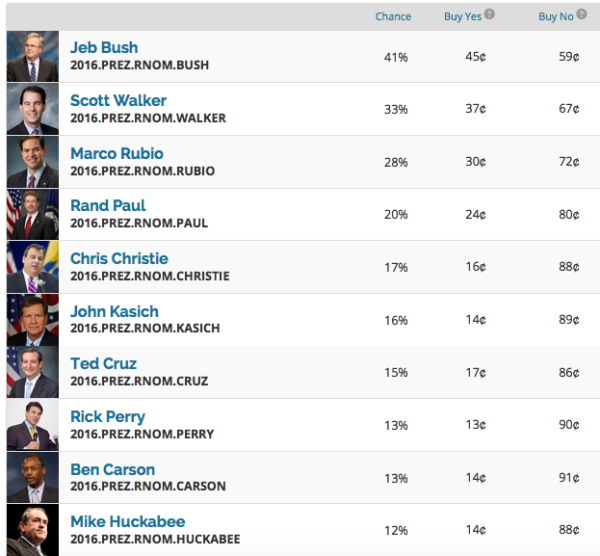

There’s one quite serious design flaw, which ought to be easy to fix. Unlike the IEM (or Intrade for that matter), short positions in multiple contracts referencing the same event are not margin-linked. To see the consequences of this, consider the prices of contracts in the heavily populated Republican nomination market:

These are just 10 of the 17 available contracts, and the list is likely to expand further. According to the prices at last trade, there’s a 102% chance that the nominee will be Bush, Walker or Rubio, and a 208% chance that it will be one of these ten. If one buys the “no” side of all ten contracts at the quoted prices at a cost of $8.10, a payoff of at least $9 is guaranteed, since the party will have at most one nominee. That’s a risk-free return of at least 11% over a year and a quarter.

This mispricing would vanish in an instant if the cost of buying a set of contracts were limited to the worst case loss, as indeed was the case on Intrade (IEM allows the purchase and sale of bundles at par, which amounts to the same thing.) Then buying the “no” side of the top two contracts would cost $0.26 instead of $1.26, and shorting the top three would be free.

If the exchange were to manage a switch to margin-linked shorts, all those currently holding no positions would make a windfall gain as prices snap into line with a no-arbitrage condition. Furthermore, algorithmic traders would jump into the market to exploit new arbitrage opportunities as they appear. Such algos have been active on IEM for a while now, and were responsible for a good portion of transactions on Intrade.

Despite this one design flaw, I expect that these markets will be tracked closely as the election approaches, and that liquidity will increase quite dramatically. This despite the fact that traders are entering into negative-sum bets with each other, which ought to be impossible under the common prior assumption. The arbitrage conditions will come to be more closely approximated as the time to contract expiration diminishes, especially in markets with few active contracts (such as that for the winning party). But unless the flaw is fixed, the translation of prices into probabilities will require a good deal of care.

If it walks like a bet, talks like a bet, and quacks like a bet, it’s a bet. Calling it a Prediction Market doesn’t change a thing, so far as I can see. Election results are no different from sports books. Public policy on gambling is pretty well settled, so I don’t see how this should be treated separately. And we have plenty of empirical data to show that permitting gambling on real economy input prices (beyond legitimate user hedging) is bad public policy and hurts real economy players more than benefitting them.

Thumbs down, bad idea.

Too bizarre, given enough capital it seems we can even monetize opinions and “instincts”. I’m aware this is in a round about way what equity markets always have been but I’m sensing, at present, there is less a need to “rationalize” what are effectively irrational hunches. So long as the facade is numerical in nature the framing can be completely unscientific and unstable. Doesn’t this contain a clue within? Stop using exchange value. Why extend exchange value into this territory despite its dismal record at solving all our other human problems (social stability, ecology, etc.)? It is not a rhetorical question. I really want to know what people think will be the benefit of this or anything similar.

Anyone know of a good way to lever up these futures bets?