Yves here. This is an important element of why income inequality is becoming institutionalized in the US. And notice the difference in impact by gender.

By Melissa S. Kearney, Professor at the Department of Economics, University of Maryland and Phillip B. Levine, A. Barton Hepburn and Katherine Coman Professor of Economics, Wellesley College. Originally published at VoxEU

Compared to other developed countries, the US ranks high on income inequality and low on social mobility. This could be particularly concerning if such a trend is self-perpetuating. In this column, the authors argue that there is a causal relationship between income inequality and high school dropout rates among disadvantaged youth. In particular, moving from a low-inequality to a high-inequality state increases the likelihood that a male student from a low socioeconomic status drops out of high school by 4.1 percentage points. The lack of opportunity for disadvantaged students, therefore, may be self-perpetuating.

High Inequality and Low Social Mobility: The Great Gatsby Curve

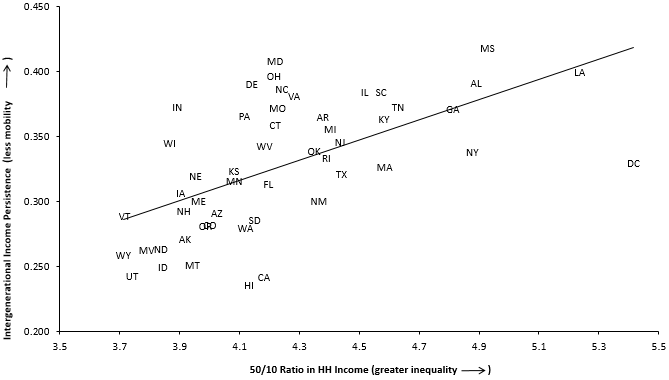

Compared to other developed countries, the US ranks high in income inequality and low in social mobility. International comparisons suggest that these measures are related; highly unequal countries tend to have low social mobility, as measured by intergenerational income persistence (Corak 2006). Alan Krueger, a former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, popularised this relationship as the ‘the Great Gatsby curve’. Combining our own data with data from Chetty et al. (2014), we construct a similar Great Gatsby curve for states in the US, shown in Figure 1, which resembles the international pattern (Kearney and Levine 2014a).

Figure 1. The Great Gatsby curve in the US

Notes: Income persistence is the relative mobility measure obtained from Chetty, et al. (2014). The 50/10 ratios are calculated by the authors.

If equality of opportunity were to prevail in a society, one would expect to see high social mobility, all else equal. There is reason for concern, then, that the US ranks poorly on the Great Gatsby curve, casting some doubt on the proposition that a child’s chances of success are independent of her family background.

High Income Inequality and School Dropout Rates in the US

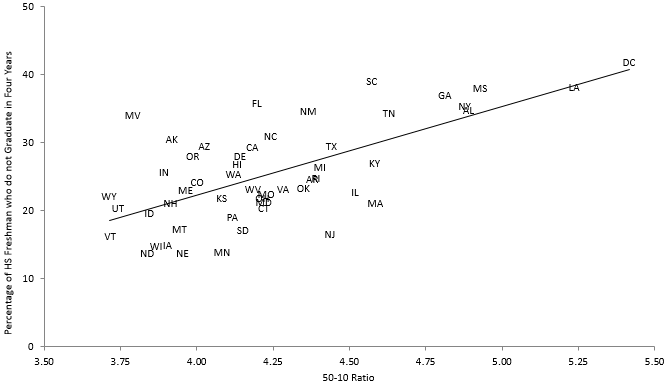

There is particular cause for concern, however, if the US’ position on the Great Gatsby curve is somehow self-perpetuating. That is, if high inequality and low mobility affect the behaviour of disadvantaged youth in a way that further diminishes their chances of success, inequality may begin to look something like a vicious circle. This is the question we investigate in this column. In particular, we examine whether high income inequality (as measured as the gap between the bottom and middle of the income distribution) and low social mobility have a causal impact on high school dropout rates among disadvantaged youth—a decision that has important consequences for their ability to climb the economic ladder. Figure 2 shows that income inequality and dropout rates across states are correlated. The purpose of this column is to assess whether this correlation reflects a causal relationship between the two.

Figure 2. Relationship between inequality and rate of high-school non-completion

To measure income inequality, we focus on the ratio of the 50th percentile of the income distribution to the 10th percentile. We focus on this measure because the distance between the low-end and the middle of the income distribution seems more relevant to disadvantaged youth than is the distance to the top of the distribution. Our data confirm that dropout rates are more responsive to the 50/10 ratio than other measures of the income distribution. To measure social mobility, we use the intergenerational income persistence measure provided by Chetty et al. (2014), which captures the change in the child’s percentile rank for a one percentile increase in the parents’ rank. As a proxy for adolescents’ socioeconomic status (SES), we use the educational attainment of an individual’s mother. Although this is not a perfect measure, it is strongly correlated with a child’s socioeconomic status, and is available across the datasets we use.

Income inequality in the US has grown in recent decades, but this is largely attributable to growth in incomes at the top of the distribution. By contrast, lower-tail inequality, as measured by the 50/10 ratio, has remained relatively stable. The same is true of social mobility. However, there is substantial, persistent variation in lower-tail inequality and social mobility across states and metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). We exploit this persistent geographic variation to explore the effects of inequality and mobility on the future economic prospects of disadvantaged youth, captured in this analysis by their decision to drop out of high school.

Although we are interested in the causal impact of both income inequality and social mobility on dropout rates, inequality and mobility are highly correlated and so it is difficult to tease apart the independent effect of each. For ease of exposition, we refer to income inequality as the explanatory variable of main interest, rather than repeatedly noting that we are interested in both inequality and mobility. Similarly, for ease of exposition, we will refer to variation in inequality across states, although we also consider variation across metropolitan statistical areas.

In our empirical analysis, we assess whether youth with low socioeconomic status in persistently high inequality locations are relatively more likely to drop out high school. In high inequality states, higher dropout rates across the socioeconomic spectrum would signal that it is something else about the state that is the cause. If inequality has a causal impact, however, we would expect to see those at the bottom of the economic ladder affected the most, which is precisely what we find.

• We find that a one point increase in the 50/10 ratio—about equivalent to moving from a low-inequality state to a high-inequality state—increases the likelihood that a low-socioeconomic status male student drops out of high school by 4.1 percentage points.

• By contrast, we find a small and statistically insignificant impact for low-socioeconomic status female students.

The finding that income inequality leads to lower rates of educational investment among lower income youth contradicts the predictions of a standard human-capital model, which predicts that when the returns to education are greater, an individual should seek to obtain more education. To consider this directly, we estimate an augmented model that includes a measure of the wage differential between high-school graduates and dropouts. Controlling for this wage premium does not alter the estimated positive effect of the 50/10 ratio and high school dropout rates. But at the same time, the data do indicate a negative relationship between the wage premium and high school dropout rates. In other words, the data clearly indicate offsetting effects.

Inequality in the form of wage returns does have the presumed positive effect, while overall household level income inequality has a negative effect on educational outcomes for low-income youth.

Is it Only an Effect of Income Inequality?

A limitation in our methodology is that we may be confusing the effect of inequality with other persistent differences across states that are correlated with inequality and have a disproportionate effect on the educational outcomes of low-income youth. Plausible examples include other features of the income distribution, the industrial composition of the labour market, or the demographic characteristics of a state (like the minority composition or fraction of single parent households). We run horse-race models directly comparing the effects of these conditions on the dropout rate of low-income youth to that of lower-tail income inequality. In every case, the data clearly show that the gap between the bottom and the middle of the income distribution leads to lower rates of high school completion among low-socioeconomic status youth, and the magnitude of that estimated effect is remarkably consistent across specifications.

We then run a series of analyses aimed at identifying mediating factors driving the link between income inequality and high school dropout rates. We consider whether the observed link is being driven by rates of residential segregation by race or income, or by public school financing. The data do not offer support for these mechanisms.

We also empirically explore one final alternative explanation. It is possible that the relationship we observe is attributable to the distribution of innate ability in the population under consideration. Perhaps low-income youth in more unequal places are simply of lower ability, for whatever reason. If this were the case, our results would reflect something about the underlying ability of the population, rather than income inequality as such. To investigate this possibility, we incorporate into the model the test scores of low-income students as a proxy for ability. Including AFQT scores reduces our estimate of the impact of inequality on high school dropout rates somewhat but we still find a strong relationship. All of these approaches support the notion that inequality is causally related to the likelihood of dropping out of high school among low-socioeconomic youth.

The Self-Perpetuating Impact of the Lack of Opportunity

So why does greater income inequality increase the dropout rate among low-income high school students? There is a class of theories that we are not able to directly test empirically that remains a viable set of candidate explanations – namely, theories focused on individuals’ perceptions of their own identity (Akerlof and Kranton 2000, Watson and McLanahan 2011), their relative societal position (Luttmer 2005), or their perceived chances of their own success (Kearney and Levine 2014b). We hypothesise that the observed relationship can be explained by the ‘economic despair’ model described in Kearney and Levine (2014b). That model focused on the decisions of young, unmarried women to have children, but the explanatory value of the model readily extends to dropout behaviour. The idea is that an increase in lower-tail inequality widens the gap between low-socioeconomic status youth and the middle-class, which in turn makes economic success look increasingly out of reach from the perspective of low-income youth. The perceived likelihood of climbing the economic ladder may fall to a level that no longer warrants continued investment in education, leading the student to drop out.

If, as our results suggest, high inequality and low mobility affect the behaviour of low-income students in a way that further diminishes their chances of success, a lack of opportunity for disadvantaged students may be self-perpetuating. This conclusion highlights the importance of policies that give low-income youth reasons to believe they have opportunities to climb the economic ladder, along with policies that make those opportunities real.

See original post for references

Interesting contrast, that Utah and Vermont are both among the best for income equality (and graduation and mobility, of course). One has the highest birth rate in the US, the other second-lowest.

Utah may have a high birth rate (due to the high population of Mormons), but it also is a very family-oriented place. Mormon families aren’t averse to education — note the popularity of schools like BYU — and I think that is to be admired.

I seem to recall a women’s right to vote starting there too. The problem is they are isolationist within Utah and/or Mormons. They’ve aligned with the GOP to be left alone.

The Mormon church might dominate, but it’s pretty active in the lives of its members. Poor Mormons don’t attract new members after all.

“Poor Mormons don’t attract new members after all.”

I don’t know why you think that. I expect that like most wealthy today, rich Mormons tend to associate with other rich people (except at church; congregations outside Utah tend to have large economic spectrums), and other rich people tend to be much less open to the LDS message. Also, many Mormons live outside the US in poorer countries where missionary work can be very successful, at least at getting people baptized LDS.

Also poor LDS young adults go on proselyting missions too, and have expenses covered by the church’s general missionary fund.

With regards to women’s right to vote, it was done by the territorial legislature in 1869, as part of a curious compromise between LDS leadership and non-LDS territorial government. Opponents of polygamy foolishly hoped that women voters would reject polygamy and weaken control of the church over territorial government. The opposite happened, of course, and LDS women proved even more ardent defenders of the “curious institution” of polygamy. Also, Utah is in THE WEST, where almost no non-Mormon women lived before 1900, so it made the LDS voting block even stronger. The right was no longer recognized after 1887, via an act of the US Congress.

http://historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/statehood_and_the_progressive_era/womenssuffrageinutah.html

Growth in LDS adherents is on par with the US population growth:

http://religiondispatches.org/mormon-numbers-not-adding-up/

I’d agree with their conclusion about low mobility affects the behaviour. If the result is the same, with or without effort (degree, high-school or college), then why make the effort?

If cronyism is visible then the most likely guarantor of success/mobility is to become a crony….

I remember an article from the Economist from maybe a decade ago. The gist of that particular article (or at least my interpretation) was that connections, not innovations, is the way to become successful (wealthy) entrepreneur. Not quite an indication of a meritocratic world/economy….

Not graduating means getting stuck in the informal economy, and crime. The lumpenproletariat is never going to gain class conscious. It’s bad for everyone.

But it makes sense, you see no future, you get drunk and high every day, even if you graduate the best you get is a job tarring roofs, I can see how those things pile up.

People need to tar roofs. The question is whether it pays enough to be part of society.

That’s absolutely correct

And vice versa. Coming from a family connected to the informal economy and criminal justice system makes one less likely to graduate from an accredited high school.

What state is “MV” (near the lower-left corner of Figure 1)? Should this be “NV”?

Great to see the focus on this, although the authors seem pretty timid. May be self-perpetuating? If high inequality and low mobility affect behavior? Are economists still having trouble actually acknowledging the systemic oppression and injustice of trickle down economics?

We don’t have enough data for the economics profession to satisfy itself conclusively that who your parents are determines whether you get arrested or get a college degree?

This is somewhat tangential because having a particular class/group of people who endemically don’t graduate from High School is obviously very bad; but, if more people across the board didn’t graduate from high school, it might be worth wondering how bad a thing that would be.

“Credentialism” as I see it is one of the worst things going on in the economy and society right now. Having a high school diploma function as something that *actively imparts* zero value and can only possibly *actively hinder* someone by his not having it seems a bad system to me. Should everyone have a qualification for having completed academic secondary education? It’s obviously not exactly suited for many people — and I don’t mean it’s only unsuited for lower class people, it’s unsuited for plenty of middle class and rich people, too. Why not give them more direct skills training, why not funnel them into jobs to gain experience? Why not let a qualification that says one has received an academic secondary education say “this person has an interest in and ability for academic subjects?”

I think the strain of people being judged by their particular credentials is a poor one, and perhaps the expectation of universal high school graduation negatively contributes to that. Universal secondary education was, after all, largely devised as a form of social control. What should replace it? I don’t know, but I am very sure that the education system needs to be drastically and radically reformed, in almost every single way. In general I’m thinking more and more that the less time people, any people of any age group, spent outside of formal institutions, the better. Yes, this is all a bit of rambling, sorry.

Not graduating from high school often means low literacy and numeracy. People who can’t read can’t make informed choices about lots of things. People who can’t do math beyond simple arithmetic are vulnerable to scams and predatory lending.

A high school diploma should probably mean more than ‘absolutely basic competence,’ but that’s what it means in a lot of places. I think it’s a very distinct issue from credentialism.

You make a good point. Unfortunately, students who make it to high school with poor reading and math skills typically don’t get much better at those skills in high school. However, there may be a slim minority who can improve their skills in high school.

It would be helpful to have more relevant classes/courses in high school, such as technical and other types of skills training, where perhaps the basic reading and math skills could be incorporated, as the student sees how relevant and necessary these are.

That said, I don’t think the PTB give a stuff if US citizens are dumb as posts. They like us ripe for the picking and fleecing. And if some become criminals? Well they either become useful to the PTB on the black market, or the heavily militarized PD will be permitted to murder them if they get out of hand.

Am I cynical? No I think I’m being realistic. Isn’t this what’s happening now?

Educated citizens may become better informed and start demanding better treatment. If you’re not well educated and can’t think critically? Well, good deal for the 1%.

There are more critical thinkers here (percentage wise) – educated or not, I have no access to academic files – than I have encountered amongst ‘educated’ people in life.

Main stream media can thrive profitably, even as we graduate more and more ‘educated people.’ That seems to indicate a low correlation between being educated and being able to think critically.

What do we teach our students?

Computer programming – future not too bright, with outsourcing and that visa program.

Manufacturing – why?

Philosophy – huh?

English – to become a human reporter so you can compete with robot reporters?

Bartending – that job is long gone.

Medicine – being a surgeon is not a sure thing and worse, robots can do anesthesia now.

Law – well, too many lawyers since at least the 1500’s when Shakespeare was writing plays.

Robot repairing – no. Robots repair robots.

I mean, what should we teach our kids?

1) That the economy, like all human activity, like humans, is a subset of the environment.

2) That resources on a finite planet are finite.

3) That a functioning environment provides “ecosystem services” that humans either cannot replicate for less than a gazillion dollars or cannot replicate at all.

4) That we’re seriously screwed, and soon, if we don’t get a handle on 1-3.

This is just a sampling, of course. My point being, there are already too many corporate flunkies and billionaires (slavering over the possibility of looting public education), as well as ground-down ordinary folk just desperate for their kids to get a paycheck some day, who insist that the point of education is to stamp out students prepared for specific work. (The corporate types because they don’t want to do two weeks of training when they hire someone, and want to have an excuse for their outsourcing.)

As you note, who knows how long some industries will be around, if they still are. We need at least some of the upcoming generation trained in thinking critically and bravely.

(Side note: bartending is gone? When did that happen? Who serves drinks in bars now?)

Actually, robots are being built that can provide almost any kind of drink you might order at a bar. The main thing they cannot do is lend a sympathetic ear to those who need someone to talk to.

IIRC there was a link here in the past couple of days referring to such robots.

I wasn’t doubting the capacity of machines to dispense beverages. I was just questioning whether their deployment had already happened.

I’m not sure that such service positions really will go the way of the dodo. Japan has had beer available in vending machines for decades, and Japanese still go to bars where humans wait on them. Of course social habits can and do change, but I’m not positive that people will whole-heartedly embrace a robot serving them a beer.

More likely, big businesses will deploy robots to cut costs and put pressure on human employees, just like they have with self-checkout machines. Small businesses will continue to rely on human beings, whom they may treat well or poorly, but those employees will have fewer options. And holdouts like me will still want to deal with human beings because as dumb as they can be, computers are worse.

Well yeah, ask nearly any high school teacher and they’ll argue this from experience. I’m pretty certain we should be past the point of needing data to validate this.

Thank you for writing this important article! Indeed, income inequality is the root of our education problem. Reagan’s report “A nation at risk” was misleading. Our rich kids do just as well as rich kids in other countries. For example, only 80% of kids go to high schools in mainland China and high schools are ranked based on test scores. On the other hand, when you compare the average U.S. high school to the top Chinese high school, of course the Chinese students look better… but it’s FAMILY INCOME that is the deciding factor. I co-wrote this book and website. http://weaponsofmassdeception.org/

What we have now is a corporate overlay on our public schools which serve as the answer to our “problem” via common core and its tests… we are witnessing a massive scam.