As the world has floundered in low growth post-crisis, with advanced economies still suffering with credit overhangs and hypertrophied, largely unreformed financial services sectors, it has become acceptable, even among Serious Economists, to question the logic that a bigger financial sector is necessarily better. Of course, the logic of “more finance, please” was never stated in those terms; it was presented in the voodoo of “financial deepening,” meaning, in layperson’s terms, that more access to more types of financial products and services would be a boon. For instance, one argument often made in favor of more robust financial services is that they allow for consumers to engage in “lifetime smoothing” of spending. That basically means if times are bad or an individual has a big investment they to make, he can borrow against future earnings. But we have seen how well that works in practice. Most people have an optimistic bias, so they will tend to underestimate how long it will take them to get back to their old level of income, assuming that even happens, which makes it too easy for them to rationalize borrowing rather than going into radical belt tightening ASAP. And we’ve seen, dramatically, on how college debt pushers get students to take on debt to “invest” in their education, when for many, the payoff never comes.

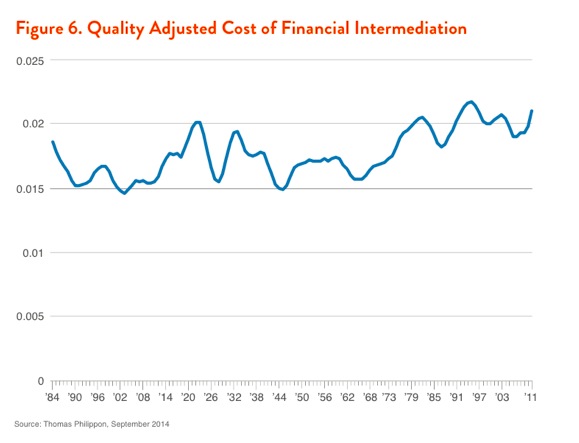

Moreover, despite an enormous increase activity and widespread use of technology, costs of financial intermediation have increased, as Walter Turbewille shows, citing a study by Thomas Philippon:

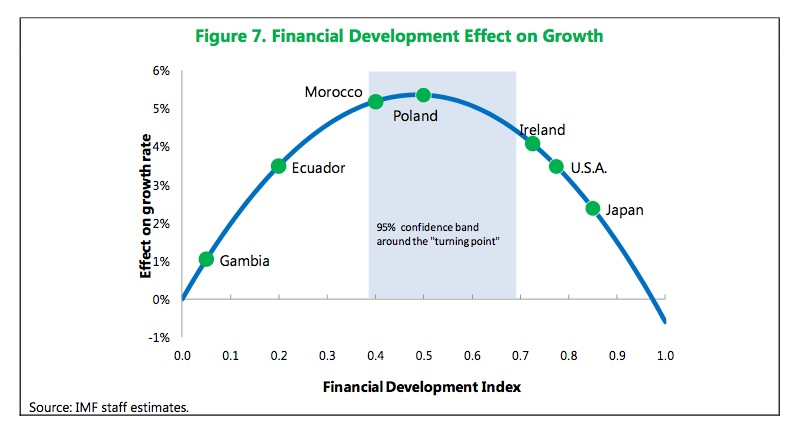

But the recent IMF paper, Rethinking Financial Deepening: Stability and Growth in Emerging Markets, is particularly deadly. Even though it focused on the impact of financial development on growth in emerging markets, its authors clearly viewed the findings as germane to advanced economies. Their conclusion was that the growth benefits of financial deepening were positive only up to a certain point, and after that point, increased depth became a drag. But what is most surprising about the IMF paper is that the growth benefit of more complex and extensive banking systems topped out at a comparatively low level of size and sophistication. We’ve embedded the paper at the end of this post and strongly urge you to read it in full.

The contribution of the IMF paper is that the authors developed a new index to do a comprehensive job of capturing financial activity. Previous work had tended to look either at the size and sophistication of financial institutions, or the depth and complexity of financial markets. The new index incorporates both aspects of financial activity, as well as incorporating access. The writers concede that their measure is still imperfect, but is an improvement over other approaches. They also stress that they are well aware of the issue of establishing that the relationship between the size and complexity of the financial sector is causal, and not a mere correlation:

Empirically, establishing causality from finance to economic growth has been a key challenge. King and Levine (1993) were the first to address this issue in a cross-country regression context. Their paper found that initial levels of financial depth—approximated by the size of the banking system relative to GDP—could predict subsequent growth rates over extended periods, even when controlling for other explanatory variables. Stock market depth was also incorporated later by Levine and Zervos (1998), with the finding that causality went from finance to growth. These results held up with further refinements of the approach, by using instrumental variables (Levine, Loayza, and Beck 2000). In the 2000s, the empirical work continued to evolve with the application of dynamic panel data techniques, using lagged values of the financial variables as instruments and controlling for other determinants of growth (Beck and Levine 2004). The present paper follows this last approach, using similar control variables and econometric techniques to ensure that the relationship is not one of simple correlations but of causality that goes from finance to growth.

This is the money chart:

The authors have a more sophisticated and nuanced assessment than “Having a financial sector that is more developed than Poland’s is a bad idea.” From the paper:

There is no one particular point of “too much finance” that holds for all countries at all times. The shape and the location of the bell may differ across countries depending on country characteristics including income levels, institutions, and regulatory and supervisory quality. In other words, a country to the right of the average “too much finance” range may still be at its optimum if it has above average quality of regulations and supervision; conversely, a country to the left of the range with weak institutions may have reached its maximum already.

This implies that countries like the US, UK, and Japan before its crisis, went pedal to the metal in the wrong direction by deregulating institutions and markets at the same time. That policy shift, in combination with overt and covert subsidies, fostered explosive growth in products and trading volumes, particularly is the least regulated sectors.

The authors used the subcomponents of their index to decompose why “too much finance” hurt growth and whether certain aspects of increased financial activity might still be salutary. They concluded that excessive financialization hurt total factor productivity. The most commonly cited mechanism for that is the brain drain: that top college graduates, and in particular, highly talented mathematicians, physicists, and computer professionals get sucked into Wall Street when they could be curing cancer or developing new materials that would reduce the demands that we make on resources. And the “curing cancer” issue is no exaggeration. I had one reader provide a long, detailed anecdote which I was told I could not quote because it might expose him and the individual, in which he interviewed a medical researcher who had written important papers in cancer research. She professed to have a keen interest in finance but it was clear that her real motivation was she would immediately triple her pay by changing careers.

The IMF team did find that expanding access (as in letting more companies and individuals able to use existing financial products and services) was positive for growth:

Specifically, access has a positive linear relationship with growth, while efficiency on its own does not have a robust positive association with long-term growth. This implies that countries that may have reached the maximum benefits in terms of growth from deepening financial institutions and

markets may still reap further growth benefits from better access. As an example, Chile stands out as a country with an above average FD index, with deep and efficient financial institutions, but could gain from greater access to both institutions and markets

Again, the US is going in the wrong direction as more and more people are unbanked.

The IMF paper is generally in line with the argument that banking should be boring, meaning that complexity, opacity, and leverage typically work far more for the benefit of the financier and at the expense of customers and society at large. Frances Coppola tries to turn that argument on its head and say that banking, particularly retail banking, should be fascinating. Huh?

At least in the US, the perception of boredom has a lot to do with one’s status, which generally means pay, and the caliber of one’s colleagues, which means how socially elite they are (a function of credentialing and sometimes education). In the old days when banks did character-based lending, the branch manager was typically a middle-of-the-pack performer in the bank credit officer training program, and those credit officers were typically good but not stellar academic performers at pretty good colleges. In England, retail banking in the 1980s was populated heavily by people with only a high school education; the old British “clearers” (clearing banks) were a great path for upward mobility for numerate, industrious working class men.

If Coppola has dealt much with retail banks recently, she’d know that the trend in the US has been to further de-skill the branches and turn them into retail stores (my bank even calls them stores) by not allowing lending decisions to take place at branches, but to have them serve as front ends for account opening and loan transaction processing. Retail loans are scored using standardized metrics, with the badly flawed FICO score as a major input.

Moreover, I was an investment banker and the work content was boring. It was largely repetitive and did not get much better as one became more senior, save as in most organizations, client interaction became more important (but at Goldman, that was handled mainly by the salesmen in the Investment Banking Services Department; the product specialists provided analysis for the sales efforts and transaction execution). It nevertheless required smart people due to the extremely lean staffing most firms maintained (everyone was constantly juggling far too many deadlines and reprioritizing during the day) and to justify the fees. Of course, at more senior levels, internal coordination and jockeying for resources, aka politics, became more important, even at a Goldman that worked very hard at keeping that down to the bare minimum.

And to confirm that my view is not dated, consider this recent sighting from the Financial Times:

The work is dull, the pay flat and your colleagues lousy. But that could well be your lot in financial services, according to a global survey that has uncovered deep frustrations at the heart of the industry.

According to the survey, carried out between January and March by Options Group, a New York-based executive search and consulting firm, just one-fifth of participants said they were content with their job, their firm, their pay and their prospects. Half of the 100 people interviewed — in a range of mostly senior positions at banks, brokers and asset managers — said they were unhappy on all four fronts.

Mind you, this survey is of the people who have more power, control, and scope, and thus should be more satisfied with their jobs than average incumbents. But this survey reveals that what has drawn people to banking in recent decades is the allure of the money, and once they start making such lofty pay and have such narrow skills, they can’t get off the greasy pole without taking a very big drop in status and income. And in some fields, the antipathy was large even before the post-crisis people led to more aggressive internal jockeying as most businesses showed flattening growth. For instance, in the early 1990s, when derivatives were the hot new thing and Morgan Stanley was one of the up and coming players, Frank Partnoy wrote in his book Fiasco how his colleagues they’d rather do anything other than sell derivatives (you had to be dedicated to ripping off your client, or as they put it, “ripping off their face” or “blowing them up”), including digging ditches, if they could make the same amount of money.

So the notion of moving to more simple-minded financial services, and having people who would like the sort of job that that sort of industry would provide work in it, is much to be desired. In the early 1980s, the banking industry on average had pay levels similar to that of other private sector jobs. While it seems hard to think that we can get back there from here, having finance be perceived to be just another line of work, as opposed to something special, would be a big step in the right direction.

IMF-Rethinking-Financial-Deepening

IMF Rethinking Financial Deepening

The first step is to stop scamming oneself. The second step is to stop scamming others.

Humanity lived for thousands of years without much in the way of “financial engineering” and “financial products”, and surprisingly enough, thrived (when the banks weren’t fomenting war and panic, that is).

If we could outlaw unregulated, fraudulent banking, we could probably outlaw war. Think about it.

Humanity also lived for thousands of years without “growth”. And now, kicking and screaming, that’s what we are going back to.

Humanity also lived for thousands of years without “growth”

The dark ages?? Feudal systems of government??

The so called dark ages and feudal systems are recent history. The jump in economic growth in very recent history (last 200 years or so) can be attributed to a combination of (i) cheap energy, (ii) an industrial revolution that made it easier to rapidly deplete natural resources, and (iii) compounding debt. Without cheap energy and an inexhaustible supply of resources, the myth of perpetual economic growth is going to die a painful death.

Yes. If you look back at the demise of great empires in the early history of humanity, say from the Bronze Age through Iron Age Rome, the story is the same. Control of resources (copper, tin, charcoal, iron ore, wheat, etc), an expanding population, a large standing army and a cheap labor force (slavery) is paramount, and when that runs out, “growth” is hampered and the “empire” crumbles (for instance, every heard of the Mitanni? or the Hurrians?). With Industrial Age Britain, it was cheap coal, a headstart over industrial competitors, an impoverished workforce and a standing army. When that ran out, the game ended. We’ll see how well our current world economy does as the oil markets become more chaotic.

You are joking, right?

The only time the European population shrank was the Plague Years. Until WWI, that is….that managed to set world population back for half a generation, coupled with the Great Depression and WWII.

There’s a great difference between Growth and Groaf, as Yves puts it. We’ve been having more of the latter, since Reagan.

There is such a thing as carrying capacity for any collection of biota inhabiting a given ecosystem. I guess when the oil runs out, we’ll find out all about it.

I’ve been reading Matthew Josephson’s book about Gould, Harriman, Morgan, Rockefeller and Hill and it seems to me that whatever interlude of boring banking we had here in the USA was a brief abberation and deviation from the American norm.

That’s a retort to Coppola no guy could get away with: “Hun?”

Fixed.

I work in plant science and we not too infrequently pick up disaffected people from finance looking for a more rewarding career. Of course the problem is that they have to start at the bottom and get a PhD, and then move into a relatively low-paying job. They have to get used to drinking wine at home and champagne only when they visit old friends!

I somehow think that the explanation touted above, that finance causes a brain-drain on other sectors, could only come from people associated with finance who have:

1. a slightly overinflated sense of their own ability

2. less idea about the abilities of people outside of finance.

If we can’t pick up locals with the right talent we scout globally, taking people most commonly from across Europe, Asia and S. America. I suggest the same is true at the top of finance, that there is a global job market, making country by country brain-drains of dubious relevance. Thus I suggest people go looking for more convincing explanations. Some ideas from the top of my head that might also be wrong:

A. There are only a finite number of reasonable risks in any economy and that this number is loosely related to size. Inflated finance relative to GDP therefore implies a higher risk threshold, leading to instability and drag on growth.

B. More finance means higher rates of broad money creation and destruction, relative to the size of the broad money base. Thus any instability is magnified into bubbles and crashes through more sensitive feed forward loops, leading to drags on growth.

C. Size of the financial industry is related to flux of money from ordinary people into tax havens where it serves no useful purpose, rather than facilitating the flux of goods and services around the economy.

Personally, I like B.

If by “plant science” you mean botany, then it seems that you can proffer a cogent understanding of “growth”.

If, when you write -“we… pick up disaffected people from finance looking for a more rewarding career”…you mean people wanting to reclaim their sanity. I believe that was one of the points of the post.

As far as “job markets”. May I humbly suggest “The Great Transformation” by Karl Polanyi. Excerpt;

“…The effects on the lives of the people were awful beyond description. Indeed, human society would have been annihilated but for protective countermoves which blunted the action of this self-destructive mechanism.

Social history in the nineteenth century was thus the result of a double movement: the extension of the market organization in respect to genuine commodities was accompanied by its restriction in respect to FICTITIOUS ones. While on the one hand markets spread all over the face of the globe and the amount of goods involved grew to unbelievable proportions, on the other hand a network of measures and policies was integrated into powerful institutions designed to check the action of the market relative to labor, land, and money…” (emphasis mine)

To your “A, B and C”, Frederick Soddy had some valuable insight in “Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt”. Excerpt;

“Debts are subject to the laws of mathematics rather than physics. Unlike wealth, which is subject to the laws of thermodynamics, debts do not rot with old age and are not consumed in the process of living. On the contrary, they grow at so much per cent per annum, by the well-known mathematical laws of simple and compound interest. The former applies when the interest is periodically paid, the latter when it is not paid. For sufficient reason, the process of compound interest is physically impossible, though the process of compound decrement is physically common enough. Because the former leads with passage of time ever more and more rapidly to infinity, which, like minus one, is not a physical but a mathematical quantity, whereas the latter leads always more slowly towards zero, which is, as we have seen, the lower limit of physical quantities.

It is this underlying confusion between wealth and debt which has made such a tragedy of the scientific era. It is fundamentally ingrained in the Western mentality and, could it be straightened out, a scientific civilisation might, at long last, yet be put on the right road.”

Unfortunately, Yves, you have completely misunderstood the point of my post.

I have now been writing for over four years about the deep structural problems in retail banking. We focus far too much on investment banking and pay far too little attention to retail banking. Your observation that retail banks have become “stores”, with deskilled workers whose job is simply to move products, is correct, but I was way ahead of you on this. Unlike you, I worked in retail banking. I worked for Midland Bank (now HSBC’s retail arm) while it was de-skilling its branches and turning them into shops: it was the first UK bank to do so. The transformation of retail banks into shops, and the consequences of that for the industry, is the theme of this post I wrote back in 2012:

http://coppolacomment.blogspot.co.uk/2012/11/supermarket-banking.html

It is my view that the deliberate draining of talent from retail banking coupled with severe pressure to generate profits in what is a low-margin, cut-throat industry (yes, it is RETAIL banking I am talking about) is the direct cause of the swathes of mis-selling and underwriting fraud that we have seen in recent decades.

Retail banking is now perceived as boring, mundane, poorly paid and not sexy. Investment banking, by contrast, is exciting, varied, wonderfully well paid and…..well, you can guess the rest. It is this framing that I wish to challenge, because I think it is incredibly damaging to retail banking.

Retail banking has become boring, not because the job of lending and deposit-taking is intrinsically dull but because we have made it so by deliberate downgrading of the skills and responsibilities of front-line retail staff. The consequences have been disastrous. This has to change. Somehow, we have to make it interesting again. Describing it as “boring” does not in any way help to achieve this.

I am also amazed that you use the “banking should be boring” meme in a post devoted to a piece of IMF research into the economic role of finance. At the INET conference on May 6, Christine Lagarde took issue with Elizabeth Warren for saying “banking should be boring”. Lagarde said she fundamentally disagreed with this. Like me, she questioned how providing finance to the real economy could possibly be regarded as boring. Her comments were written up by Rona Foroohar in TIME magazine: a link to Rona’s article is at the foot of my post.

We agree that retail banking is not what it used to be. However, there are many issues missing from your account. Including them considerably changes the picture of how we got to be where we are and what might be done.

Retail lending was never a terribly prestigious activity in banking institutions, but when banks were regulated as utilities, they played an important and recognized role as important anchors of communities, and that alone was a lure when society was less stratified than it is now. The branch manager was a respected position, and for many, that was ample reward when communities were more stable than now. One would hardly call these old school bankers creative or terribly talented. Internally, retail branch managers where were the middle-of-the-pack graduates of two-year credit officer training programs wound up. The best graduates of those programs got MBAs and went to Wall Street. In the late 1970s, a good 10% of the incoming MBA class at Harvard came from big bank credit officer programs. The best of the ones that remained at banks were put on big corporate lending. And the other route to prestige and power at a bank was through rising in the ranks. Power and prestige was directly related to the number of people you had working for you.

This all started breaking down in the early 1980s as the banks began their long push for dereglation, which was driven in large measure by envy of investment banking profit margins and profits. That morphed in the 1990s and 2000s into envy of hedge fund profits. I saw this first hand, since I was hired into McKinsey to help with this effort and worked extensively on the Citibank account. As of the early 1980s, as testament that this train had already left the barn, the second highest paid person at Citigroup was Mark Kessenich,the head of the money markets division. This was seen as scandalous within Citi as it upset the traditional bank pecking order. One of Kessenich’s most important direct reports was Paul DeRosa, who can lay claim, but doesn’t, to having invented the swaps market (he does take credit for having invented caps and collars). DeRosa trained a generation of swaps professionals, who in large measure decamped to other banks and investment banks. By the later 1980s, Kessenich and DeRosa were running their own hedge fund, Eastbridge Capital.

By the mid-1980s, the increased role of bond markets in credit intermediation, and the high profits resulting from the strong scale factors in that business (network effects and high minimum scale requirements) was pressuring both investment banks and commercial banks. Even McKinsey was losing out in campus recruiting and facing significant losses of mid-level staff, which put the firm in a funk. McKinsey was pushing securitization (“you’ll be on this bus or under the bus”) as having insurmountable economic advantages, and regulators also looked favorably upon it, seeing it as making more efficient use of bank capital.

The move towards predatory practices also started much earlier than you indicate. For instance, McKinsey did what amounted to the first tricks and traps study, a study on “pricing” checking services. By tweaking features and introducing some “gotchas,” the McKinsey study increased the profitability of the checking product by $30 million a year, a big number in the 1980s. Needless to say, the firm started selling similar studies to other big bank clients. Banks adopted this line of thinking and brought it in house. This is certainly a use of talent, but is it socially productive?

Securitization changed the role of bank branches radically. It no longer made sense to train credit officers to make local decisions, since loan products needed to be standardized to facilitate their bundling and sale to investors. The main branch lending products, consumer mortgages and credit cards, were being significantly securitized by the late 1980s-early 1990s. Even for the old branch managers who still had the skills to do credit analysis and character based loans had little scope to do them. When those higher-skilled branch manager retired, they were replaced with retail store managers. The branch was no longer the nexus of credit decisions. They were replaced with score-based lending, reviewed and approved elsewhere in the retail division.

Thus while it is true that retail banking has been de-skilled, the economics of the industry simply won’t support the old high-touch lending model for small loans. I find it perverse that you decry regulations when it was regulations that assured banks high enough profit margins to allow banks to play the role you’d like to see them play. And I don’t see how you roll back securitization to go back to high-discretion lending. As Amar Bhide (professor of entrepreneurship as well as former proprietary trader) has written, banks aren’t in the business of small business lending and haven’t been for some time, despite the Fed’s bizarre talk of low interest rates supposedly stimulating small business lending. Small business lending is in fact either collateralized (against business real estate, to finance equipment, etc) or credit cards/small limit credit lines that are personally guaranteed by the business owner (and therefore based on his FICO).

As Georgetown Law professor and securitization/payment systems expert Adam Levitin added via e-mail:

Amends in advance….

I just want to splay myself out in this comment like staring up into the sun…. in remote field of tall grass and flowers… just soaking it up….. the moment… peaceful clarity about the reality – we – all share… for better or worse… I would not have it – any – other way….

Skippy… absolutely sublime… thank you~

If I bet $10k that Dallas wins some game, I risk ten thousand. If I was impetuous and foolish when I made the bet, I might have second thoughts. In that case I hedge the bet by betting $9k that the Cowboys lose. If I’d only bet $1000 in the first place, I’d have saved the bookie’s commission on $19,000. We don’t much care about what happens to the fools who do this with their money. But what about the banks that do it with ours?

Credit Default Swaps, like derivatives in general, add costs to transactions without adding value to the real products that they may represent. In that way they parasitize the real economy from which the abstract instruments must [ultimately] be derived. So whether the fools are politicians who facilitate the fraud of derivatives, or respected bankers and investors, or the schmuck at the local off track betting bar, the practice of hedging, futures speculation, CDSs or whatever harm the Human Race. They threaten our economy and therefore our lives.

Concentration of wealth is harmful to Human culture and a threat to our survival. It’s perhaps the greatest threat that civilization has always faced. Consider this analogy: In a hypothetical casino card game the house takes 5% of every pot. If 10% of the money at the table is on average played on each hand, then the house takes 0.5% of the money in the game on each rake. After 200 hands, 100% of the money that is on average at the table has been taken by the house. The only way the game may continue is to have new money come to it. The winners, of course, smell the new blood and even anticipate it greedily. And the biggest winner over a time is always the house. Until the free market ideologues took over, the biggest difference between a casino bank and finance was that the gaming house took a bigger cut of the handle.

The main problem with bringing money into the present based on future income streams is the future is always uncertain in regard to maintaining those income streams and in no small measure due to debt repayment effect on real economy demand. Analysis seems to show that if the creation of private debt versus the overall total of sovereign government and private entity creation exceeds 40% a financial crash will occur.

https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/33741/FGEXPND.png

That’s an interesting IMF title. It is basically acknowledging it is a narrow, limited study of the issue. To have to rethink something suggests that somebody seriously believes financial deepening is a good thing in the first place. And to still frame it within GDP growth demonstrates a lack of willingness to address the limitations of GDP. We have a distributional problem (inequality), not an aggregate problem (growth).

The purpose of make finance bigger than the minimum needed is predation, fraud, theft, looting. Just like with law and medicine and education and transportation and national security and other areas where our entire growth paradigm – both leftists and rightists – says that more is better.

Trust me, orthodox economists and policy makers do believe financial deepening is a good thing. For one of many examples, see this discussion of Timothy Geithner’s views:

https://www.creditwritedowns.com/2011/02/geithner-dont-shrink-financial-services.html

Timmy’s an economist? Or maybe a policy maker? I just thought he was a fool and a clown.

I guess I’m of a different, much more critical mind reading this kind of stuff. I haven’t met in person or read anything that sounds sincere from our nation’s thought leaders. It all sounds like PR (or just straight BS). They are selling something, not describing authentically held beliefs about how best to observe and address reality. They are enabling fraud, not fighting it. IMO, of course.

Geithner doesn’t even pretend to say the financial system is good for average Americans in that post. He says he personally doesn’t like shrinking financial services – appealing to people’s good faith and sense of fair play that surely a college educated government bureaucrat in a fancy suit must be taking into account the public good when coming to his own personal preferences.

But if you have never experienced such a public ethos from the leadership class – and if you don’t think cars and car companies are good things(!) – you read something completely different. What I read from Geithner’s statement is his acknowledgement that there is no public purpose for making finance bigger. It’s to benefit banks, not the banking system. It’s to keep things going like they are, not change to make the world better.

The smarminess, insincerity, lack of concreteness, and general manipulative quality of his words seeps through everything, from the implication that financial reform has been meaningful to the insinuation he cares about others because he learned while living overseas how to look at life from the perspective of other people.

The Saudis are trying to have their cake and eat it, too. They can go to war against Western-style banksters, but they aren’t going to win in Yemen without them. Or with them, either, IMO.

This was a reply to susan the other below…it got misplaced (my error).

I agree with what washunate says, 100%.

The Elite are in their own little world, and we will be tearing down their privacy gates in the near future. Because: what cannot continue, will not continue.

Hey, thanks Demeter. You reminded me of an episode from a few years ago that makes me chuckle at how disingenuous the mindset is. Our elites can’t even keep their logic straight within a single presentation.

Charlie Munger at Berkshire Hathaway was telling students at the University of Michigan to thank God for the bank bailouts but learn to suck it in and cope if you yourself are having trouble. Because of course the government can’t just go around handing out money to people. It is pure comedic gold.

http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/billionaire-bailout-recipient-to-america-suck-it-in-and-cope-buddy-20100921

Analyzing the depth and complexity of the financial institutions against the breadth and depth of the market. Kinda like looking at the relationship between money and resources. Makes me think of the bedrock wisdom of the Saudis when they say they are not at war wit US shale, they are at war with US credit. Because even tho’ Mom was spiritually right when she said “you can be anything you want to be” she just wasn’t being realistic. The Saudis are realistically at war with the lack of reality practiced in the US. Technically we could create a growth industry by processing human cadavers into various highly synthesized grades of oil. But really, it’s like Wolfgang Schaeuble said a while back: We are over-banked. And hopefully all the banks will realize this too late and experience a total industry collapse before anybody can be mobilized to save their greedy butts. Least of all the sociopaths they made rich. I mean really.

Hugely important topic; will re-read more fully later.

Meanwhile, for those interested in this topic, another useful link about the Finance Curse:

http://www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/Finance_Curse_Final.pdf

I’m curious where Cyprus would fall on the inverted parabola graph. Their financial sector was huge.

I guess even a gigantic parasite like the IMF recognizes when its host is nearly dead.

And the tapeworm exits the dying gut, off in search of a healthier host…

My experience with retail banking was, if not exactly fascinating, interesting.

A few years ago my small company was growing fast. It seemed like A Good Idea At The Time to move our accounts to a Big Five bank (a mid-sized city downtown branch) and establish a Relationship, in case we needed it.

I did love looking around the bank’s lobby, a beautiful art deco interior with 40 or 50 customer windows. Two were in use. I made a point of introducing myself to the Manager. A month later, she was gone. As was her replacement a month after that. And customer service? Pick on a phone in the lobby and they’d put you through to someone in Mumbai. No long distance charges!

So much for relationship banking. Our current bank has an office somewhere, but I’ve yet to see it. The internet is as close to it as I want to come.

Looks like Gambia’s a 10-bagger! To hell with regulation.

shlt I remember way back this dude I worked with was a fairly big-time Wall Street sell-side industry analyst. I was about 25 and somehow got hired as one myself. God only knows how that happened, but anyway.

One day he was even more run-down looking than usual. His stocks had taken a beating and I guess so had he. So he said when he’s at the grocery store he looks at the guy bagging groceries and feels an envious longing, that he’d rather be making money doing that, he said, than what he’s doing here and now (back then, obviously). He was quite sincere. that I know for sure

He seemed to have a decent soul and probably a desire to express a craftsman’s skill at something real. Money isn’t real. That’s the problem. And no matter what predictions you make about it, you will be wrong most of the time and when you’re right it will be impossible to know if you were just lucky that time. So no matter what you do, if that’s all you do, is move money around, you’re really doing nothing at all. It doesn’t seem like that to your mind, but it does to your soul. That’s why if you have a soul it gets hard and you feel the presence of an absence that grows and grows and finally you yourself realize you’ve disapppeared entirely into that absence. That’s when the panic sets in

Don’t panic.

With a mind like yours, there must be plenty of other options for employment ;-)

“…That’s why if you have a soul it gets hard and you feel the presence of an absence that grows and grows and finally you yourself realize you’ve disapppeared entirely into that absence. That’s when the panic sets in.”

That’s when you move on. Those that stick long-term never panic because they’re psychopaths.

No soul , no panic , no problem – for them , at least. For the rest of us , panic would be one rational response to being under the thumbs of a bunch of billionaire psychos.

Pitchforks would be another.